Abstract

Little is known about the role of cognitive social capital among war-affected youth in low- and middle-income countries. We examined the longitudinal association between cognitive social capital and mental health (depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms), functioning, and received social support of children in Burundi. Data were obtained from face-to-face interviews with 176 children over three measurement occasions over the span of 4-months. Cognitive social capital measured the degree to which children believed their community was trustworthy and cohesive. Mental health measures included the Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS) (Birleson, 1981), the Child Posttraumatic Symptom Scale (Foa, Johnson, & Feeny, 2001), and a locally constructed scale of functional impairment. Children reported received social support by listing whether they received different types of social support from self-selected key individuals. Cross-lagged path analytic modeling evaluated relationships between cognitive social capital, symptoms and received support separately over baseline (T1), 6-week follow-up (T2), and 4-month follow-up (T3). Each concept was treated and analyzed as a continuous score using manifest indicators. Significant associations between study variables were unidirectional. Cognitive social capital was associated with decreased depression between T1 and T2 (B=−0.22, p<.001) and T2 and T3 (β=−0.25, p<.001), and with functional impairment between T1 and T2 (β=−0.15, p=.005) and T2 and T3 (β=−0.14, p=.005); no association was found for PTSD symptoms at either time point. Cognitive social capital was associated with increased social support between T1 and T2 (β=0.16, p=.002) and T2 and T3 (β=0.16, p=.002). In this longitudinal study, cognitive social capital was related to a declining trajectory of children’s mental health problems and increases in social support. Interventions that improve community relations in war-affected communities may alter the trajectories of resource loss and gain with conflict-affected children.

Keywords: Resilience, social capital, children, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Depression, functioning, War

Exposure to war and armed conflict is associated with adverse mental health outcomes in children and adolescents (Barenbaum, Ruchkin, & Schwab-Stone, 2004; Betancourt & Khan, 2008). Although challenging to quantify these problems, a recent systematic review of 17 studies including 7,920 children found the pooled prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was 47%, depression 43%, and anxiety disorders 27%, demonstrating a high burden of these disorders (Attanayake et al., 2009). Mental disorders are associated with negative outcomes during childhood and adolescence. For example, depression in childhood can affect social functioning, academic achievement, and raise the risk for substance abuse and suicidal ideation (Birmaher, Ryan, & Williamson, 1996; Fergusson, Horwood, Ridder, & Beautrais, 2005). In post-conflict settings, a number of factors protect children from pernicious mental health effects of adversity and promote their well-being. A recent systematic review identified protective and promotive effects that exist at multiple levels of children’s social ecology (i.e., at individual, family, peer/school, and community levels) (Tol, Song, & Jordans, 2013). Although some qualitative studies (Betancourt et al., 2011) document the importance of social and community relations in post conflict settings, the concept of social capital has received little empirical attention.

Within low- and middle-income countries, social resources buffer the effects of exposure to potentially traumatic life events (PTEs) and aid in community healing (Betancourt, Newnham, McBain, & Brennan, 2013; Gorst-Unsworth & Goldenberg, 1998; Hobfoll, Mancini, Hall, Canetti, & Bonanno, 2011; Panter-Brick, Goodman, Tol, & Eggerman, 2011; Veling, Hall, & Joosse, 2013). Social capital is a useful concept that encapsulates social resources available to a person through their social environment (Bourdieu, 1986; Inaba, 2013). It is often measured as a individual (Lin, 2001) or aggregate community resource (Kawachi, Takao, & Subramanian, 2013) and delineated into cognitive and structural domains (De Silva, McKenzie, Harpham, & Huttly, 2005). Structural social capital focuses on social networks and civic or community group membership and participation while cognitive social capital is concerned with perceptions of trust and reciprocity within communities.

Cognitive social capital, the focus of the current investigation, is associated with better mental health outcomes. In a systematic review, of research mostly conducted in high resource settings, greater cognitive social capital was protective against common mental disorders (De Silva et al., 2005) and children’s mental health. Greater social capital is also associated with an increased sense of safety (Dallago et al., 2009) and lower risk for a variety of public health problems in children including smoking, and obesity. Although cognitive social capital is associated with fewer mental health problems in adult populations living in low-income countries (De Silva, Huttly, Harpham, & Kenward, 2006), the association between social capital and children’s mental health within similar contexts has not been investigated. We would expect that cognitive social capital would exert a positive influence on mental health of children in these contexts, similar to what was found in higher resource communities (De Silva et al., 2005).

The majority of studies examining social capital and mental health have relied on cross-sectional designs. These studies are helpful in identifying correlates that, if modified, may increase mental health. However, such studies are limited with regard to concluding the directionality of relationships and only tell one side of the story; reciprocal relationships may be occurring. In addition to the evidence that suggests cognitive social capital is associated with better mental health (De Silva et al., 2005), relationships between mental health and protective factors can exhibit reverse causation. Evidence from the adult trauma literature suggests that declines in the availability of social resources are related to psychological distress following a variety of potentially traumatic events (Bonanno, Brewin, Kaniasty, & La Greca, 2010; Hall, Bonanno, Bolton, & Bass, unpublished results; Heath, Hall, Russ, Canetti, & Hobfoll, 2012; Kaniasty & Norris, 2008). To our knowledge, no longitudinal study has investigated whether social capital is a resource for children affected by war and ongoing violence and political instability. The present study utilizes a three-wave crossed-lagged panel design to evaluate the nature and direction of effects between cognitive social capital, mental health and received social support.

We modeled reverse causality in the current study for several theoretical reasons. According to the social causation/social drift framework (Kaniasty & Norris, 2008), social causation predicts that losses to social resources are associated with increased mental health problems. Social drift suggests that mental health problems can lead to decreased social resources. This model is supported and extended by Hobfoll’s conservation of resources theory that posits loss to valued resources following exposure to traumatic events leads to mental health problems; loss spirals may occur when mental health problems in turn lead to further losses (Hobfoll, 1989). We also sought to evaluate the presence of gain spirals, that is, whether the presence of one form of interpersonal resources could subsequently lead to gains in another. Cognitive social capital may increase the likelihood that children received social support as they may be more likely to seek this support if they believe in the trustworthiness of those in their environment. Conversely, receiving greater social support could in turn bolster the belief of community trust.

Given that cognitive social capital exists as an individual’s perception, it is plausible that depressive symptoms could negatively influence the perception of the trustworthiness of others (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010) and PTSD symptoms could undermine feelings of safety, trust and confidence in ones community (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), and contribute to avoidance of social contact, leading to reductions in cognitive social capital. Contrariwise, greater cognitive social capital could influence mental health outcomes by attenuating the cognitions regarding perceived isolation (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010), danger and fear (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), and negative biases (Alloy et al., 2006) known to exacerbate mental health problems.

Poor mood, irritability (King, Taft, King, Hammond, & Stone, 2006) and lack of interest in socialization could lead to alienation or rejection. General impairment in functioning could lead to dependency and help seeking and if this is met with rejection or miscarried support, cognitive social capital may also be affected. With regard to received social support, it is plausible that increased support could lead to more positive view of the community, thereby increasing cognitive social capital.

We hypothesize that greater cognitive social capital is associated with decreases in mental health symptoms and functional impairment over time. Beyond reductions in symptoms and impairment, we hypothesize that greater cognitive social capital will confer other salutary benefits. Beliefs in the trustworthiness and cohesiveness in one’s community may lead to a desire or openness to receive social support; therefore, greater cognitive social capital is expected to relate to greater received social support. Based on our theoretical arguments above, we also hypothesize that reciprocal effects would occur such that mental health symptom severity would lead to losses in cognitive social capital and that higher reported received social support would relate to greater cognitive social capital.

Method

Participants

Burundi experienced cyclical political instability and violence between Hutu and Tutsi ethnic groups since 1962. The eastern African country has a population of 8.5 million and ranks as the third poorest country in the world with regard to health, education and income (United Nations, 2011). Widespread exposure to violence, displacement of 1.2 million people and the death of 300,000 people occurred during the civil war that started in 1993. The data obtained for the current study are from the waitlist control participants (N=176) of a cluster randomized trial aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of a school-based mental health intervention in Burundi (Tol et al., 2014).

Data collection occurred between 2006 and 2007 in 7 randomly selected public schools within the northwestern province of Cibitoke. Although peace agreements were signed in 2003, and armed violence significantly reduced, this province continued to experience threat of violence from rebel groups that remained active in the area during the time of study. A qualitative study showed that the armed conflict and poverty were perceived to be associated with an interrelated set of children’s problems, including war-related problems at the individual, family (large-scale loss of parents, abuse by foster families, increased family conflicts over land), peer (distrust between Hutu and Tutsi peers), and community levels (loss of social solidarity, increased accusations of supernatural harm, ethnic hate and distrust) (Tol et al, 2014). Continued violence occurred throughout the data collection period. A total of 270 children were screened for the waitlist control arm and 176 children met criteria for inclusion. These criteria were exposure to one or more PTEs and scoring above distress cutoff scores (Tol et al., 2014; Ventevogel, Komproe, Jordans, Feo, & de Jong, 2014). Cut-off scores followed common conventions for mental health outcomes (see Tol et al., 2014 for a complete explanation of study inclusion). Written informed consent/assent was obtained from parents and children. The study was approved through the IRB at VU University Amsterdam in the Netherlands and secondary data analysis was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Measures

All measures were selected based on formative qualitative fieldwork conducted in northwestern Burundi (focus groups, semi-structured interviews with children and caregivers, key informant interviews with traditional/religious healers, teachers, community health workers, clergy and staff of organizations assisting war-affected children) (Tol, Jordans, Reis, & de Jong, 2008). All interviews were transcribed verbatim and submitted to content analysis, which informed instrument selection/adaptation. All measures were submitted to bilingual translation, independent bilingual conceptual review, blind-back translation, focus groups and piloting with target population (van Ommeren et al., 1999). They were also submitted to validation against a psychiatric diagnostic interview. The results of the validation study and thorough description of the study methods are found in Ventevogel et al. (2014). Trained interviewers administered the measures within participants’ schools.

Cognitive Social Capital

A social capital measure was developed locally, building on the Short Adapted Social Capital scale (SASC) (De Silva, Harpham, et al., 2006). The measure was constructed to assess cognitive social capital, which measures the child’s perception of the trust, cohesion and reciprocity within their community. Formative work described above revealed that community social ties had been damaged by conflict. Two items from the SASC measuring trust in other children and children getting along with other children were retained. Additional locally relevant items were added to account for social processes identified in the formative research, asking about the child’s perception of sense of community, the community’s respect for rules and social norms, and whether community members helped each other. The scale contained 6 items, with responses on a 4-point likert-type scale ranging from 7-28. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .70.

Depressive symptoms

The Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS) (Birleson, 1981) is an 18 item measure that assesses depressive symptoms. Responses were answered on a 3-point scale with a range between 0-36. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .71.

Posttraumatic stress symptoms

The Child Posttraumatic Symptom Scale (Foa et al., 2001) is a widely used measure for PTSD in children. It utilizes 17 symptoms characterizing PTSD in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) nosology. Items are answered on a 4-point likert-type scale; values range from 0-51. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .79.

Functional impairment

A locally relevant scale was developed using a mixed methods approach (Tol, Komproe, Jordans, Susanty, & de Jong, 2011). This scale contained 10 items that inquired about impairment in daily activities such as hygiene, playing, household chores, studying, and religious activities. Responses were on a 4-point likert-type scale, with a range from 10-40. Higher values indicated greater impairment. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .81.

Received social support

The total number of people providing support to a child was ascertained using the Social Support Inventory Scheme (Paardekooper, de Jong, & Hermanns, 1999). Children could name up to five people from whom they receive support across four dimensions: material (helping with school fee); emotional (listening to problems); guidance (providing advice); or play (singing). The number of possible network members that provided support is obtained by summing across the four domains to create an index of support ranging from 0–20.

Model covariates

Participant characteristics were obtained for child’s sex, age, displacement status (0=no; 1=yes), household size, and family composition (0=both parents not residing in home; 1=both parents residing in home). Exposure (0=no; 1=yes) to PTEs related to armed conflict was measured using 11 items obtained through a free listing activity with 23 local HealthNet TPO Burundi staff. Items named by 5 or more staff were selected for inclusion. Examples include witnessing destruction of houses, physical violence, bombings and killings, and experiencing torture.

Data Analysis

Cross-lagged path analysis is a widely used methodology to assess potentially casual associations among constructs measured in longitudinal observational study designs. Four cross-lagged panel models using manifest indicators were specified in the present study to assess the reciprocal association between cognitive social capital and symptoms of PTSD and depression, functional impairment, and received support. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML). For each relationship tested, four path analytic models were evaluated, first to include covariates and then to achieve model parsimony. First, a baseline model (Model 1) was specified with all pathways freely estimated (e.g., autoregressive, and cross-lagged paths). Next, the fit of this model was compared to a model that included covariates to address potential confounding (Model 2). Confounders were selected based on prior literature and on theoretical grounds. In Model 3, equality constraints were imposed on autoregressive paths (from each construct regressed on itself at an earlier measurement occasion), and finally, in Model 4 equality constraints were imposed on cross-lagged paths. Sample descriptive statistics and reliability estimates were calculated using Stata MP 12.1 (StataCorp, 2012). Statistical assumptions were evaluated using various Stata commands including kernel density plots (kdensity), Cook and Weisberg test (hettest), Shapiro-Wilk tests (swilk) and normality tests (ladder). Depression symptom severity and functioning were non-normally distributed and were transformed using square root and log transformations. Path analyses were conducted with Mplus Version 7 (Muthen & Muthen, 2012).

Model 1 was compared to Model 2 using the difference in Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values. The BIC value can be used to test nonnested models. A 10-point BIC difference represents a 150:1 likelihood (p<.05) that the model with the lower BIC value fits best and a difference greater than 10 indicates very strong support for model superiority(Raftery, 1995). Model 3 and Model 4 were both compared to the baseline model and the relative fit of these models was evaluated using chi-square difference tests with a p value set at .05. Overall model fit was assessed using the chi-square goodness of fit statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI(Bentler, 1990)), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI(Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Tucker & Lewis, 1973)), the root mean square of approximation (RMSEA(Browne & Cudeck, 1993)), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Non-statistically significant chi-square values, CFI values exceeding .95, TLI above .90, RMSEA below .08, and SRMR below .05 were considered evidence of excellent model fit. Effect sizes for the cross-lagged pathways were interpreted with the conventions for regression coefficients (<.29 = small, .30–.49 = medium, and >.50 = large(Cohen, 1988)).

Results

The sample was balanced with regard to sex (53.4% boys). The average age was 12 years old (SD=2.17; range 6 – 16). Slightly more than half the sample reported displacement (55.8%) and not living with both parents (57.1%). The mean household size was 6.75 (SD=2.17) people. Exposure to PTEs related to the conflict was common, with an average of 4.13 (SD=2.04) different types of events reported. Table 1 lists means, standard deviations and Cronbach’s alpha for all study variables. Covariance coverage values exceeded 90% for all pairwise relationships. Parameters were estimated using FIML for 10 children lost to follow-up; however, four children were missing data on model covariates, and were dropped from the analysis.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for main study variables

| Variable |

Baseline

Mean (SD) |

6-Week Follow-up

Mean (SD) |

4-Month Follow-up

Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Social Capital | 13.97 (2.77) | 14.01 (2.77) | 14.35 (3.06) |

| Depressive symptoms | 11.28 (5.08) | 8.58 (4.94) | 8.47 (4.35) |

| PTSD symptoms | 16.30 (7.35) | 13.82 (9.45) | 10.67 (8.41) |

| Functional Impairment | 15.78 (5.53) | 14.68 (5.14) | 14.57 (5.34) |

| Social support network | 12.63 (4.46) | 13.83 (4.07) | 13.64 (4.10) |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Cognitive Social capital and depressive symptoms

We first tested models to determine whether the model with covariates was superior based on BIC values. Model 2 was superior to Model 1 with a BIC difference of 73.94 (p<.05) therefore Model 2 (with covariates) was retained. Model 2 did not differ statistically from Model 3 (Δχ2(df=2)=0.30, p>.05) or Model 4 (Δχ2(df=2)=0.98, p>.05), indicating that the constructs were stable over time and the strength of the cross-lagged effects were not different between the two measurement lags. Model 4, a fully constrained model including covariates provided excellent fit to the data χ2(df=32)=39.12, p=.18, CFI=.97, TLI=.95, RMSEA=.04 (.00–.07), SRMR=.05. Figure 1 shows the standardized autoregressive and cross-lagged path coefficients.

Figure 1.

Standardized structural equation modeling results for the relationship between social capital and depressive symptoms

Social capital was related to less depression symptoms from T1 to T2 (β=−0.22, p<.001) and from T2 to T3 (β=−0.25, p<.001). The reciprocal paths for depressive symptoms relating to less social capital were not statistically significant between T1 and T2 (p=.06), and from T2 to T3 (p=.06). Greater exposure to PTEs (β=0.23, p<.001) and larger number of people living in the home (β=−0.01, p<.001) was associated with greater depressive symptoms, while being in a home with both parents was associated with less depressive symptoms (β=−0.24, p=.01).

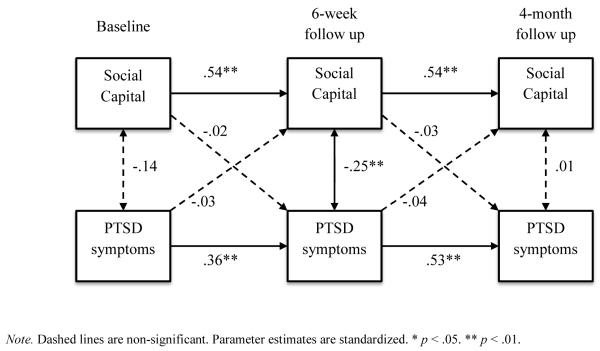

Cognitive Social capital and PTSD symptoms

Model 2 was superior to Model 1 with a BIC difference of 109.55 (p<.05) therefore Model 2 was retained. Like the above analysis, Model 2 did not differ statistically from Model 3 (Δχ2(df=2)=0.21, p>.05) or Model 4 (Δχ2(df=2)=2.12, p>.05). Model 4 provided excellent fit to the data χ2(df=32)=40.10, p=.15, CFI=.96, TLI=.94, RMSEA=.04 (.00–.07), SRMR=.05. Figure 2. shows the standardized autoregressive and cross-lagged path coefficients. No cross-lagged coefficients were significant. Greater exposure to PTEs (β=0.25, p<.001) was associated with greater PTSD symptoms severity.

Figure 2.

Standardized structural equation modeling results for the relationship between social capital and PTSD symptoms

Cognitive Social capital and functional impairment

Model 2 was superior to Model 1 with a BIC difference of 19.14 (p<.05) therefore Model 2 was retained. Model 2 did not differ statistically from Model 3 (Δχ2(df=2)=−0.68, p>.05) or Model 4 (Δχ2(df=2)=0.92, p>.05). Model 4 provided excellent fit to the data χ2(df=32)=40.10, p=.15, CFI=.96, TLI=.94, RMSEA=.04 (.00–.07), SRMR=.05. Figure 3. shows the standardized autoregressive and cross-lagged path coefficients. Social capital was related to less functional impairment from T1 to T2 (β=−0.15, p=.005) and from T2 to T3 (β=−0.14, p=.005). The reciprocal paths for functional impairment relating to less social capital were not significant (p values=.387). Displacement was associated with greater functional impairment (β=0.17, p=.03).

Figure 3.

Standardized structural equation modeling results for the relationship between social capital and functional impairment

Cognitive Social capital and social support network

Model 2 was superior to Model 1 with a BIC difference of 79.77 (p<.05) therefore Model 2 was retained. Model 2 did not differ statistically from Model 3 (Δχ2(df=2)=−0.66, p>.05) or Model 4 (Δχ2(df=2)=2.39, p>.05). Model 4 provided adequate fit to the data χ2(df=32)=44.15, p=.07, CFI=.93, TLI=.89, RMSEA=.05 (.00–.08), SRMR=.05. Figure 4 shows the standardized autoregressive and cross-lagged path coefficients. Social capital was related to greater social support network from T1 to T2 (β=0.16, p=.002) and from T2 to T3 (β=0.16, p=.002). The reciprocal paths for social support network relating to social capital were not significant (p’s>.45). No covariates were significant in this model.

Figure 4.

Standardized structural equation modeling results for the relationship between social capital and social support network

Discussion

The present study provides the first longitudinal evidence of the role of cognitive social capital in war-affected children. Findings demonstrate a protective effect of cognitive social capital on depressive symptoms and functional impairment, as well as a promotive effect for increasing social support received. Consistent with our first hypothesis, children with higher levels of cognitive social capital had less depressive severity and functional impairment between each measurement lag. These findings extend previous research that shows a cross-sectional relationship between these constructs. This longitudinal effect was not present for PTSD symptom severity, but cross-sectional effects were noted. This is contradictory to models of PTSD that would suggest a potentially causal influence, at least on the cognitive level, between these variables. However, this is broadly consistent with a 1-year follow-up study of adolescents in Kabul, Afghanistan (Panter-Brick et al., 2011). In this study, changes in PTSD symptoms were predicted by lifetime trauma exposure, whereas changes in depressive symptoms and general psychological difficulties were predicted by quality of family relationships. Similarly, in a study of former child soldiers in Sierra Leone, community acceptance was associated with fewer symptoms of depression, but not anxiety (Betancourt et al., 2013). Together, these longitudinal studies suggest that trajectories of PTSD in war-affected children may be more strongly determined by trauma exposure, whereas supportive family and community environments may influence depressive symptoms.

In support of the second hypothesis, cognitive social capital was related to a greater received social support. This was consistently found between both measurement waves. Greater trust in the community and sense of community cohesion may influence behaviors that lead to the acquisition of support. Increases to sources of received support among children exposed to war may also lead to benefits as social relationships are associated with increases in pro-social skills (Gest, Graham-Bermann, & Hartup, 2001). The cross-lagged effects were stronger than cross-sectional associations among variables. This highlights the importance and strength of utilizing longitudinal data to draw inferences on the role of risk and protective factors for children’s mental health.

The third and fourth hypotheses were not supported; reciprocal effects were not observed. Symptoms of distress and impairment were not related to less social capital; the protective effect of social capital was maintained throughout the course of the study. This is opposite to what was noted in past studies employing similar analytic methods measuring social resources and mental health in adult trauma-exposed populations (Heath et al., 2012; Kaniasty & Norris, 2008). However, it is important to note that these studies, which informed the current investigation, were different with respect to the concepts being evaluated (social support versus cognitive social capital), followed exposure to terrorism and natural disasters, which although similar with regard to disruption to social fabric may potentiate different social-ecological realities, and measured associations in adults, which may have different patterning in their associations over time. Another critical consideration is that the measurement period in the current study may have been too short for the negative effects of these symptoms to begin to diminish cognitive social capital. It is also possible that the level of symptoms may have been too low.

Support that social network support leads to greater cognitive social capital was not shown. This may suggest that social capital is stable, even in this impoverished war zone, not influenced by received support, or that is influenced by other non-measured variables. If a child increases their number of supports, this does not lead to feeling that the community is more trustworthy or cohesive. These relationships may be unidirectional in nature, and social capital, unlike social support, is not eroded by mental health symptom severity or increased by social network support. Future studies are needed with longer follow-up periods to tease this apart.

The covariates included that were significantly associated with poorer mental health were displacement, greater exposure to PTEs, and larger number of people living in the home. Being in a home with both parents was associated with less depressive symptoms suggesting this is an important family-level protective factor. This could be a proxy of parental support that previous studies showed was protective against depression (Barber, 1999; Durakovic-Belko, Kulenovic, & Dapic, 2003), or for the availability of economic resources. It is notable that our models were improved by adding potential confounding factors. It follows that small cross-sectional studies that test relationships among few variables are at risk for larger error.

Limitations

Despite a number of strengths including the large sample size given the post-conflict setting, prospective study design, mixed methods to adapt and select instruments, and novelty of the study hypothesis, there are a number of important study limitations. Our unit of analysis was restricted to the individual- rather than the ecological/community-level, which some argue is where social capital accrues (Henderson & Whiteford, 2003) and is associated differently with mental health (De Silva et al., 2005). However, other theorists propose that social capital is an individual-level resource thereby measureable at the level of a person (Bourdieu, 1986). The sample was screened to include children with previous exposure and high levels of distress, so inferences may not generalize to children without these vulnerabilities. The measurement lags were relatively short, and cannot be compared to studies that follow populations over one or several years. It is not certain that the time periods that were used for follow-up were meaningfully related to the underlying process of change that children experience with regard to the constructs under study. This is an issue common to longitudinal research. It may take one year or more for reverse causation to be noted in these children, if at all. However, the present study allowed for a test of two different measurement lags and equality constraints in our models suggest that equivalent change in these processes over these measurement periods. Future research should continue to investigate multiple potential casual pathways between risk and protective factors to better understanding the underlying process in post-conflict contexts. It is important also to note that the sample size for the present analysis would ideally be larger than 180 cases. Although our sample approximates this number, caution should be used with regard to the expectation of the stability of these coefficients, and replication in larger samples is warranted.

Intervention implications

Mental health programing that targets the community social-ecological level continues to gain recognition as a promising approach in LMIC contexts (Batniji, Van Ommeren, & Saraceno, 2006). This is consistent with discourses in public health that advocate for engagement in a balanced framework that includes local knowledge of the signs and symptoms of distress and healing related to humanitarian crises, as well as attention to locally available resources and strengths (de Jong, 2002) This study provides needed evidence that improving the community social environment may lead to declines in mental health problems (van Ommeren, Morris, & Saxena, 2008). Children with higher cognitive social capital also reaped additional benefits of gains to their supportive social networks, a critical recovery resource (Tol, Barbui, et al., 2011; Veling et al., 2013). Given that the association is so clear and uni-directional, there is promising scope for preventive interventions that are geared towards changing cognitive social capital. These could include having children engage in peer-group activities that foster a sense of community and positive shared experiences, for example collaborative problem solving and cooperative play. Interventions that promote reconciliation in communities torn apart by conflict may more directly enhance and promote cognitive social capital by repairing the damaged social relations in conflict-affected communities (Yeomans, Forman, Herbert, & Yuen, 2010).

Question about how to develop effective community-level interventions and how to leverage social capital to enhance community resilience remain open and are promising areas of inquiry. Is social capital a modifiable risk factor for mental health problems following armed conflict? The answer is not yet clear but preliminary evidence from randomized trials of group-based interventions have begun to show that there are indeed social benefits accrued to survivors of violence (Hall et al., in press ). Developing social-ecological models of community intervention and engagement warrant greater attention, and the application of social capital theory towards healing communities from the effects of trauma is a promising area of further exploration. These effects need to be replicated in child and adolescent conflict-affected populations given that increasing social resources holds the promise of durable changes in conflict affected communities.

Research highlights.

Cognitive social capital was associated with less depression

Cognitive social capital was associated with greater social support

Change in cognitive social capital was unrelated to social support and depression

Cognitive social capital is promising for mental health prevention and promotion

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by PLAN Netherlands. Brian J. Hall, PhD was partially supported by the National Institute of Mental Health T32 in Psychiatric Epidemiology T32MH014592-35 and through the Fogarty Global Health Fellows Program (1R25TW009340-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Panzarella C, Rose DT. Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:145–156. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association, A. P. Diagnositic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Press; Washington D.C.: 2000. text revison ed. [Google Scholar]

- Attanayake V, McKay R, Joffres M, Singh S, Burkle FJ, Mills E. Prevalence of mental disorders among children exposed to war: a systematic review of 7,920 children. Medicine, Conflict and Survival. 2009;25(1):4–19. doi: 10.1080/13623690802568913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Political violence, family relations, and Palestinian youth functioning. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:206–230. [Google Scholar]

- Barenbaum J, Ruchkin V, Schwab-Stone M. The psychosocial aspects of children exposed to war: practice and policy initiatives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:41–62. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batniji R, Van Ommeren M, Saraceno B. Mental and social health in disasters: relating qualitative social science research and the Sphere standard. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1853–1864. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.050. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88(3):588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. International Review of Psychiatry. 2008;20(3):317–328. doi: 10.1080/09540260802090363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki S, Stulac SN, Barrera AE, Mushashi C, Beardslee WR. Nothing can defeat combined hands (Abashize hamwe ntakibananira): Protective processes and resilience in Rwandan children and families affected by HIV/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, McBain R, Brennan RT. Post-traumatic stress symptoms among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone: follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;203:196–202. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.113514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birleson P. The validity of depressive disorder in childhood and the development of a self-rating scale: a research report. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1981;22(1):73–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years. Part 11. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolesent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1575–1583. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, La Greca AM. Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2010;11:1–49. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387086. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson J, editor. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Greenwood; New York: 1986. pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. second ed Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New York, New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dallago L, Perkins D, Santinello M, Boyce W, Molcho M, Morgan A. Adolescent place attachment, social capital, and perceived safety: a comparison of 13 countries. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;44:148–160. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9250-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JT. Public Mental Health, Traumatic Stress and Human Rights Violations in Low-Income Countries. In: de Jong JT, editor. Trauma, War and Violence: Public mental health in socio-cultural context. Kluwer Academic Publishers; New York: 2002. pp. 1–93. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva MJ, Harpham T, Tuan T, Bartolini R, Penny ME, Huttly SR. Psychometric and cognitive validation of a social capital measurement tool in Peru and Vietnam. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(4):941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva MJ, Huttly S, Harpham T, Kenward MG. Social capital and mental health: a comparative analysis of four low income countries. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;64:5–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva MJ, McKenzie K, Harpham T, Huttly SRA. Social capital and mental illness: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59(8):619–627. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029678. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durakovic-Belko E, Kulenovic A, Dapic R. Determinants of posttraumatic adjustment in adolescents from Sarajevo who experienced war. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:27–40. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(66-72) doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Johnson KM, Feeny NC, Treadwell KRH. The child PTSD symptom scale (CPSS): A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:376–384. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Graham-Bermann SA, Hartup WW. Peer experience: Common and unique features of number of friendships, social network centrality, and sociometric status. Social Development. 2001;10:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gorst-Unsworth C, Goldenberg E. Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq: Trauma-related factors compared with social factors in exile. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172:90–94. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Joormann J. Cognition and depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:285–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Bolton P, Annan J, Kayesn D, Robinette K, Certinoglu T, Bass JK. The effect of cognitive therapy on structural social capital: Results from a randomized controlled trial among sexual violence survivors in the Democratic Republic of Congo. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301981. (in press ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Bonanno GA, Bolton P, Bass JK. A longitudinal investigation of changes in social resources associated with psychological distress among Kurdish torture survivors living in Northern Iraq. doi: 10.1002/jts.21930. (unpublished results) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(2):218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath N,M, Hall BJ, Russ E,U, Canetti D, Hobfoll SE. Reciprocal relationships between resource loss and psychological distress following exposure to political violence: An empirical investigation of COR theory’s loss spirals. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2012;25:679–695. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.628988. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.628988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S, Whiteford H. Social capital and mental health. Lancet. 2003;362(9383):505–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14150-5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Mancini AD, Hall BJ, Canetti D, Bonanno GA. The limits of resilience: Distress following chronic political violence among Palestinians. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:1400–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.022. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba Y. What’s wrong with social capital? Critques from social science. In: Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Takao S, editors. Global Perspectives on Social Capital and Health. Springer; New York, NY: 2013. pp. 323–342. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, Norris FH. Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: Sequential roles of social causation and social selection. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(3):274–281. doi: 10.1002/jts.20334. doi: 10.1002/jts.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Takao S, Subramanian SV. Introduction. In: Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Takao S, editors. Global Perspectives on Social Capital and Health. Springer; New York, NY: 2013. pp. 323–342. [Google Scholar]

- King DW, Taft C, King LA, Hammond C, Stone ER. Directionality of the Association Between Social Support and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Longitudinal Investigation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2006;36(12):2980–2992. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00138.x. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Muthen LK. Mplus. Version 7.1 Los Angeles, California: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paardekooper B, de Jong J, Hermanns JM. The psychological impact of war and the refugee situation on South Sudanese children in refugee camps in Northern Uganda: an exploratory study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40(4):529–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C, Goodman A, Tol WA, Eggerman M. Mental health and childhood adversities: a longitudinal study in Kabul, Afghanistan. Journal of American Academy Child and Adolesent Psychiatry. 2011;50:349–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.001. doi: doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . STATA. Version 12.1 College Station, TX: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tol WA, Barbui C, Galappatti A, Silove D, Betancourt TS, Souza R, van Ommeren M. Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings: linking practice and research. The Lancet. 2011;378:1581–1591. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61094-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tol WA, Jordans MD, Reis R, de Jong J. Ecological resilience: Working with child-related psychosocial resources in war-affected communities. In: Danny B, Ruth P-H, Julian DF, editors. Treating Traumatized Children. Routledge; New York, New York: USA: 2008. pp. 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tol WA, Komproe IH, Jordans M, J.D., Ndayisaba A, Ntamutumba P, Sipsma H, de Jong JTVM. School-based mental health intervention for children in war-affected Burundi: a cluster randomized trial. BMC Medicine. 2014;12(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-56. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tol WA, Komproe IH, Jordans MJ, Susanty D, de Jong JTVM. Developing a function impairment measure for children affected by political violence: a mixed methods approach in Indonesia. Internatioanl Journal of Qualitative Health Care. 2011;23:375–383. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tol WA, Song S, Jordans MJD. Annual research review: Resilience in children and adolescents living in areas of armed conflict: a systematic review of findings in low and middle-income countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12053. doi: doi:10.1111/jcpp.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program: Human Development Report 2011. UNDP; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- van Ommeren M, Morris J, Saxena S. Social and clinical interventions after conflict or other large disaster. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2008;35(3) doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Thapa SB, Makaju R, Prasain D, Bhattarai R, de Jong J. Preparing instruments for transcultural research: use of the Translation Monitoring Form with Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1999;36:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Veling W, Hall BJ, Joosse P. The association between posttraumatic stress symptoms and functional impairment during ongoing conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(2):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventevogel P, Komproe IH, Jordans MJD, Feo P, de Jong JTVM. Validation of the Kirundi versions of brief self-rating scales for common mental disorders among children in Burundi. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(36) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-36. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans PD, Forman EM, Herbert JD, Yuen E. A randomized trial of a reconciliation workshop with and without PTSD psychoeducation in Burundian sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(3):305–312. doi: 10.1002/jts.20531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]