Abstract

Objective

Psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are usually delivered once or twice weekly over several months. It is unclear whether they can be successfully delivered over a shorter period of time. This clinical trial had two goals, (1) to investigate the acceptability and efficacy of a 7-day intensive version of cognitive therapy for PTSD, and (2) to investigate whether cognitive therapy has specific treatment effects by comparing intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy with an equally credible alternative treatment.

Method

Patients with chronic PTSD (N=121) were randomly allocated to 7-day intensive or standard 3-month weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD, 3-month weekly emotion-focused supportive therapy, or a 14-week waitlist condition. Primary outcomes were PTSD symptoms and diagnosis as assessed by independent assessors and self-report. Secondary outcomes were disability, anxiety, depression, and quality of life. Measures were taken at initial assessment, 6 weeks and 14 weeks (post-treatment/wait). For groups receiving treatment, measures were also taken at 3 weeks, and follow-ups at 27 and 40 weeks after randomization. All analyses were intent-to-treat.

Results

At post-treatment/wait assessment, 73%, 77%, 43%, 7% of the intensive cognitive therapy, standard cognitive therapy, supportive therapy, and waitlist groups, respectively, had recovered from PTSD. All treatments were well tolerated and were superior to waitlist on all outcome measures, with the exception of no difference between supportive therapy and waitlist on quality of life. For primary outcomes, disability and general anxiety, intensive and standard cognitive therapy were superior to supportive therapy. Intensive cognitive therapy achieved faster symptom reduction and comparable overall outcomes to standard cognitive therapy.

Conclusions

Cognitive therapy for PTSD delivered intensively over little more than a week is as effective as cognitive therapy delivered over 3 months. Both had specific effects and were superior to supportive therapy. Intensive cognitive therapy for PTSD is a feasible and promising alternative to traditional weekly treatment.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, clinical trial, randomized controlled trial, cognitive behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, intensive treatment, treatment outcome, treatment acceptability

Introduction

A range of trauma-focused psychological treatment programs are effective for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1-3). Such treatments are usually delivered once or twice per week over the course of several months. While this is a conventional psychotherapy format, it has some potential disadvantages from a patient perspective. PTSD interferes with social and occupational functioning and it could be desirable to make more rapid progress. Furthermore, some patients find it difficult to commit to protracted psychological treatment (2). This raises the question of whether trauma-focused psychological treatment for PTSD is effective and acceptable if condensed into a shorter period of time. There is some evidence that intensive cognitive behavior therapy is effective in other anxiety disorders (4-5), but it remains unclear whether it is feasible for PTSD. Some clinicians are concerned about the risk of symptom exacerbation in the treatment of PTSD (6-7), and it is conceivable that a concentrated treatment delivery could enhance the risk of possible adverse effects.

This clinical trial had two goals. First, we investigated the acceptability and efficacy of an intensive 7-day version of cognitive therapy or PTSD (8). Standard once-weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD over three months has been shown to be highly effective and acceptable to patients (9-13). A pilot study suggested that intensive cognitive therapy for PTSD may also be effective (8). Second, we tested whether cognitive therapy for PTSD has specific treatment effects by comparing intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy with an alternative active treatment, emotion-focused supportive psychotherapy, using a broad range of outcomes including PTSD symptoms, disability, anxiety, depression, and quality of life. Cognitive therapy for PTSD has been shown to be superior to self-help interventions with limited therapist contact (9), but has not yet been compared with an equally credible alternative psychological treatment involving the same amount of therapist contact.

Method

Participants

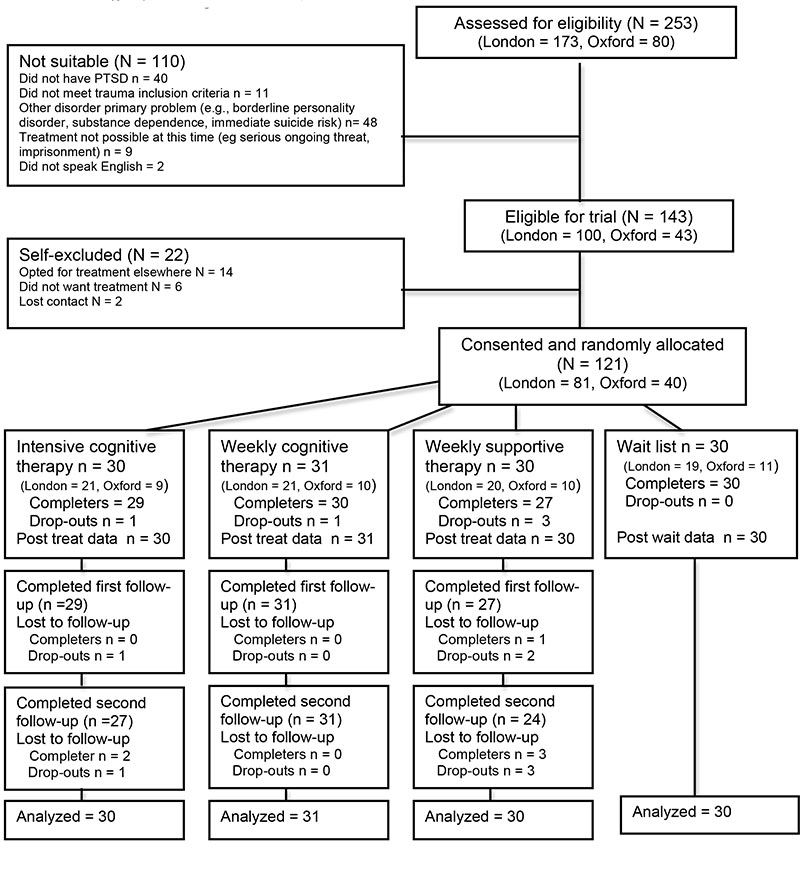

Participants (N=121) were recruited between 2003 and 2008 from consecutive referrals to a National Health Service outpatient clinic for anxiety disorders in South London, UK (n=81), or a research clinic at the University of Oxford, UK (n=40). Patients were invited to participate if they met the following inclusion criteria: they were between 18-65 years old; met diagnostic criteria for chronic PTSD as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (14); their current intrusive memories were linked to one or two discrete traumatic events in adulthood; and PTSD was the main problem. Exclusion criteria were: history of psychosis; current substance dependence; borderline personality disorder; acute serious suicide risk; treatment could not be conducted without the aid of an interpreter. Figure 1 shows the patient flow chart and Table 1 presents details on trauma, clinical, demographic and treatment characteristics. There were no group differences in any of the variables. Seventy-one patients (58.7%) were female, and 36 (29.8%) were from ethnic minorities. The most common index traumas were interpersonal violence (physical/sexual assault, 37.2%), accidents or disaster (38.0%), or traumatic death of others (7.4%). Most patients (71.9%) had a history of other traumas besides their index traumas. The majority (63.6%) had comorbid other Axis I disorders (mainly mood and anxiety disorders, substance abuse), and 19.8% had Axis II disorders (mainly obsessive-compulsive, depressive, paranoid, avoidant). Around a third (36.7%) had had previous treatment for PTSD. Patients taking psychotropic medication (29.8%) were required to be on a stable dose for two months before random allocation.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Patient Recruitment and Progress through the Randomized Controlled Trial

Table 1. Sample, Trauma and Treatment Characteristics by Treatment Condition.

| Intensive Cognitive Therapy (N = 30) | Standard Weekly Cognitive Therapy (N = 31) | Supportive Therapy (N= 30) | Waitlist (N=30) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Demographics | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Sex | Female | 18 | 60.0 | 18 | 58.1 | 17 | 56.7 | 18 | 60.0 | ||||||||

| Male | 12 | 40.0 | 13 | 43.9 | 13 | 43.4 | 12 | 40.0 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Ethnic Group | Caucasian | 22 | 73.3 | 20 | 64.5 | 22 | 73.3 | 21 | 70.0 | ||||||||

| Ethnic Minority | 8 | 26.7 | 11 | 35.5 | 8 | 26.7 | 9 | 30.0 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Age | in Years | 39.7 | 12.4 | 41.5 | 11.7 | 37.8 | 9.9 | 36.8 | 10.5 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Marital Status | Never married | 9 | 30.0 | 10 | 32.3 | 12 | 40.0 | 10 | 33.3 | ||||||||

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 3 | 10.0 | 4 | 12.9 | 4 | 13.4 | 5 | 16.7 | |||||||||

| Married/Cohabitating | 18 | 60.0 | 17 | 54.8 | 14 | 46.7 | 15 | 50.0 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Education | College/ University | 6 | 20.0 | 8 | 25.8 | 8 | 26.7 | 10 | 33.3 | ||||||||

| Higher school exam (age 18) | 1 | 3.3 | 6 | 19.4 | 6 | 20.0 | 6 | 20.0 | |||||||||

| Standard school exam (age 16) | 18 | 60.0 | 12 | 38.7 | 12 | 40.0 | 13 | 43.3 | |||||||||

| None | 5 | 16.7 | 5 | 16.1 | 4 | 13.3 | 1 | 3.3 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Current Employment | Unemployed | 7 | 23.3 | 7 | 22.6 | 9 | 30.0 | 5 | 16.7 | ||||||||

| On disability/retired | 2 | 6.7 | 3 | 9.7 | 3 | 10.0 | 3 | 10.0 | |||||||||

| Sick-leave | 7 | 23.3 | 3 | 9.7 | 5 | 16.7 | 4 | 13.3 | |||||||||

| Working full or part-time | 14 | 46.7 | 18 | 58.1 | 13 | 43.3 | 18 | 60.0 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Profession | Professional | 5 | 17.2 | 4 | 12.9 | 6 | 20.0 | 6 | 20.7 | ||||||||

| White collar | 8 | 27.6 | 17 | 54.8 | 7 | 23.3 | 12 | 41.4 | |||||||||

| Blue collar | 10 | 34.5 | 6 | 19.4 | 10 | 33.3 | 6 | 20.7 | |||||||||

| Homemaker/Student/Not working | 6 | 20.6 | 4 | 12.9 | 7 | 23.3 | 5 | 17.2 | |||||||||

| Intensive Cognitive Therapy (N = 30) | Standard Weekly Cognitive Therapy (N = 31) | Supportive Therapy (N= 30) | Waitlist (N=30) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Traumas | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Type of Main Traumatic Event | Interpersonal | ||||||||||||||||

| Violence1 | 12 | 40.0 | 12 | 38.7 | 11 | 36.7 | 10 | 33.3 | |||||||||

| Accidents/ Disaster | 11 | 36.7 | 11 | 35.5 | 14 | 46.7 | 10 | 33.3 | |||||||||

| Death/ Harm to Others | 2 | 6.7 | 1 | 3.2 | 2 | 6.7 | 4 | 13.3 | |||||||||

| Other | 5 | 16.7 | 7 | 22.6 | 3 | 10.0 | 6 | 20.0 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Time since Main Traumatic Event | 3 months - 1 year | 10 | 33.3 | 14 | 45.2 | 8 | 27.8 | 14 | 46.7 | ||||||||

| 1 to 2 years | 10 | 33.3 | 5 | 16.1 | 7 | 24.1 | 6 | 20.0 | |||||||||

| 2 to 4 years | 7 | 23.3 | 11 | 35.5 | 8 | 27.6 | 3 | 10.0 | |||||||||

| More than 4 years | 3 | 10.0 | 1 | 3.2 | 6 | 20.7 | 7 | 23.3 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| History of Other Trauma | Yes | 22 | 63.3 | 21 | 67.7 | 23 | 76.7 | 20 | 66.7 | ||||||||

| No | 8 | 26.7 | 10 | 32.3 | 7 | 23.3 | 10 | 33.3 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Reported History of Childhood Abuse | Yes | 5 | 16.7 | 2 | 6.5 | 4 | 13.3 | 3 | 10.0 | ||||||||

| No | 25 | 83.3 | 29 | 93.5 | 26 | 86.7 | 27 | 90.0 | |||||||||

| Intensive Cognitive Therapy (N = 30) | Standard Weekly Cognitive Therapy (N = 31) | Supportive Therapy (N= 30) | Waitlist (N=30) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Comorbidity | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety | Yes | 10 | 33.3 | 7 | 22.6 | 10 | 33.3 | 10 | 33.3 | ||||||||

| Disorder | No | 20 | 66.7 | 24 | 77.4 | 20 | 66.7 | 20 | 66.7 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Depressive | Yes | 12 | 40.0 | 7 | 22.6 | 11 | 36.7 | 14 | 46.7 | ||||||||

| Disorder | No | 18 | 60.0 | 24 | 77.4 | 19 | 63.3 | 16 | 53.3 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Substance | Yes | 6 | 20.0 | 6 | 19.4 | 6 | 20.0 | 2 | 6.7 | ||||||||

| Abuse | No | 24 | 80.0 | 25 | 80.6 | 24 | 80.0 | 28 | 93.3 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| History of Substance Dependence | Yes | 2 | 6.7 | 4 | 12.9 | 2 | 6.7 | 1 | 3.3 | ||||||||

| No | 28 | 93.3 | 27 | 87.1 | 28 | 93.3 | 29 | 96.7 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Axis II disorder | Yes | 7 | 23.3 | 5 | 16.1 | 4 | 13.3 | 8 | 26.7 | ||||||||

| No | 23 | 76.7 | 26 | 83.9 | 26 | 86.7 | 22 | 73.3 | |||||||||

| Intensive Cognitive Therapy (N = 30) | Standard Weekly Cognitive Therapy (N = 31) | Supportive Therapy (N= 30) | Waitlist (N=30) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Treatment History | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Previous Treatment for PTSD | Yes | 10 | 33.3 | 11 | 35.5 | 12 | 40.0 | 11 | 36.7 | ||||||||

| No | 20 | 66.7 | 20 | 64.5 | 18 | 60.0 | 19 | 63.3 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Psychotropic Medication Pre Treatment | Yes | 5 | 16.7 | 11 | 35.5 | 12 | 40.0 | 8 | 26.7 | ||||||||

| No | 25 | 83.3 | 20 | 64.5 | 18 | 60.0 | 22 | 73.3 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Changes in Medication | Discontinued before 14 Weeks in Follow-up Stayed on Medication | 1 | 20.0 | 5 | 45.5 | 3 | 25.0 | 2 | 25 | ||||||||

| 1 | 20.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 3 | 25.0 | -- | -- | ||||||||||

| 3 | 60.0 | 5 | 45.5 | 6 | 50.0 | 6 | 75 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Started Medication During Study | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Other Psychological Treatment During Study | Trauma-Related | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| For other Problems | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Intensive Cognitive Therapy (N = 30) | Standard Weekly Cognitive Therapy (N = 31) | Supportive Therapy (N= 30) | Waitlist (N=30) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Treatment Received in Trial | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Number of Sessions | Before 14 weeks | 10.13 | 2.18 | 10.10 | 3.26 | 10.27 | 3.21 | ||||||||||

| Booster | 1.90 | 0.80 | 2.07 | 1.46 | 2.20 | 1.32 | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Treatment Credibility | 23.63 | 4.40 | 24.29 | 4.60 | 22.00 | 5.12 | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Therapeutic Alliance | Patient Rating | 5.94 | 0.56 | 5.70 | 0.68 | 5.53 | 0.51 | ||||||||||

| Therapist Rating | 5.69 | 0.47 | 5.74 | 0.40 | 5.67 | 0.48 | |||||||||||

Random Allocation and Masking

If suitable for the trial and willing to participate, patients signed the informed consent form. They were then randomly allocated to one of the four trial conditions by an independent researcher who was not involved in assessing patients, using the minimization procedure (15) to stratify for sex and severity of PTSD symptoms. Assessors determining the suitability of a patient for inclusion were not informed about the stratification variables and algorithm. Assessments of treatment outcome were conducted by independent evaluators without knowledge of the patient’s treatment condition. Patients were asked not to reveal their group assignment to the evaluators. Participants were not blind to the nature of the treatment, but care was taken to create similarly positive expectations in each treatment group, by informing them that several psychological treatments were effective in PTSD and it was unknown which worked best, and by giving a detailed rationale for the treatment condition to which the patient was allocated. Patient ratings of treatment credibility (16) and therapeutic alliance scores (17) were high in all treatment conditions and did not differ (Table 1).

Treatment Conditions

Patients in all treatment conditions received up to 20 hours of treatment by the 14 week (post-treatment/wait) assessment. Sessions were spread evenly over 3 months for standard cognitive therapy and supportive therapy, whereas the main part of treatment occurred within the first 7 to 10 days of intensive cognitive therapy. The number of treatment or booster sessions received did not differ between the treatment groups (Table 1).

Standard Cognitive Therapy for PTSD

This treatment was delivered as in previous trials (9, 10), in up to 12 weekly individual sessions over the course of three months, with an optional three monthly booster sessions over the following three months. The treatment follows Ehlers and Clark’s model of PTSD (19) and aims to reduce the patient’s sense of current threat by (i) identifying and modifying excessively negative appraisals of the trauma and/or its sequelae, (ii) elaborating the trauma memory and discriminating triggers of intrusive reexperiencing, and (iii) reducing the use of cognitive strategies and behaviors (such as thought suppression, rumination, safety-seeking behaviors) that maintain the problem. Therapists followed a treatment manual (20). A description of treatment procedures is found at http://oxcadat.psy.ox.ac.uk/downloads/CT-PTSD%20Treatment%20Procedures.pdf/view. Patients were given homework assignments to complete between sessions.

7-Day Intensive Cognitive Therapy for PTSD

This treatment followed the same protocol as standard cognitive therapy, but the main part of the treatment was delivered over a much shorter period of time. In the intensive treatment phase, patients received up to 18 hours of therapy over a period of 5 to 7 working days. Treatment days usually comprised a morning and an afternoon session lasting 90 min to 2 hours, with a break for lunch. There were up to two further sessions one week and one month after the intensive period to discuss progress and homework assignments, and up to three optional monthly booster sessions. Patients receiving intensive cognitive therapy completed homework assignments parallel to those in standard cognitive therapy. However, during the intensive phase homework was more limited due to time constraints.

Emotion-focused Supportive Therapy

This non-directive treatment focused on patients’ emotional reactions rather than their cognitions. It was designed to provide a credible therapeutic alternative to control for nonspecific therapeutic factors so that observed effects of cognitive therapy could be attributed to its specific effects beyond the benefits of good therapy. Like standard cognitive therapy, it comprised up to 12 weekly individual sessions (up to 20 hours in total) over three months and optional three monthly booster sessions. Therapists followed a manual that specified procedures, building on similar treatment programs (20-21). After normalizing PTSD symptoms, the therapist gave the rationale that the trauma had left the patient with unprocessed emotions and that therapy would provide them with support and a safe context to address their unresolved emotions. Patients could freely choose what problems to discuss in the session, including any aspect of the trauma. Therapists helped patients clarify their emotions and solve problems. They did not restructure the patient’s appraisals, attempt to elaborate their trauma memories or discriminate triggers, or direct them in how to change their behavior. As homework, patients kept a daily diary of their emotional responses to the events of the week that was discussed in the following session (20).

Waitlist

Patients allocated to waitlist waited for 14 weeks before receiving treatment.

Outcome measures

Data were collected from all participants, including dropouts. Primary assessment points were at pre-treatment/wait, 6 weeks (self-reports only), and 14 weeks (post-treatment/wait). Follow-ups for treated patients were at 27 and 40 weeks after randomization. Figure 1 shows the number of patients who provided data at each assessment point. In addition, patients receiving therapy also completed self-reports of PTSD symptoms, anxiety and depression at 3 weeks.

Primary Outcome Measures

Clinician-rated PTSD symptoms

Independent assessors (trained psychologists) interviewed patients with the Clinician-Administered PTSD scale (CAPS) (22). The CAPS assesses the frequency and severity of each of the PTSD symptoms specified in DSM-IV. Interrater reliability was kappa=.95 for a PTSD diagnosis, and r=.98 for the total severity score (37 interviews, 14 interviewers, 14 raters).

Severity of PTSD symptoms

Patients completed the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (23), a self-report questionnaire measuring the overall severity of PTSD symptoms (range 0-51) that has shown good reliability and concurrent validity with other PTSD measures.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Disability

Patients completed the Sheehan Disability Scale (24) and rated the interference caused by their symptoms in their work, social life/leisure activities, and family life/home. The disability score was the sum of the ratings (range 0-30).

General Anxiety and Depression

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (25) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (26), standard 21-item self-report measures with high reliability and validity (range 0-63).

Quality of Life

Perceived quality of life was assessed with the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (27). This scale assesses the patient’s satisfaction in 14 life domains and has been shown to be reliable and valid in clinical and community samples (28).

Therapist Training and Treatment Fidelity

Therapists were qualified clinicians who had completed a clinical psychology or nurse therapist degree, and had received further training in all treatments used in this study. They had treated at least two cases with each of the therapy protocols under supervision before treating trial patients. They received weekly supervision from a senior clinician trained in all treatment modalities for weekly cases, and daily supervision for intensive cases to ensure compliance with the treatment protocols.

To further evaluate treatment integrity, a randomly selected recording from each patient was reviewed by a trained assessor for compliance with the treatment protocol, using a detailed checklist of procedures used. Only one minor deviation was discovered: one of the supportive therapy patients worked on spotting memory triggers for a few minutes. Another randomly selected session from each patient was rated for therapist competency. Cognitive therapy sessions were rated by a psychologist experienced in cognitive therapy, using an adapted version of the Cognitive Therapy Scale (29), on a scale from 0 to 6. A score of 3 is considered satisfactory, and scores of 4 and above indicate good to excellent competency. The mean score was 4.7 (SD=0.41) for standard cognitive therapy and 4.8 (SD=0.35) for intensive cognitive therapy (p>.18). Supportive Therapy sessions were evaluated for therapist competency by a counseling psychologist experienced in supportive therapy (on a scale from 0 to 6 with anchors as above, informed by ratings of dimensions of good non-directive therapy such an empathic understanding, 30). The mean rating was 4.7 (SD=0.49).

Data Analysis

All analyses were intent-to-treat, using all 121 randomly assigned participants. Dichotomous outcomes were compared with χ2 tests. Continuous outcomes were analyzed with hierarchical linear modeling (31). This analysis models random slopes and intercepts for participants, and tests the fixed effects of treatment condition and repeated assessments over time, using data from all participants. Differential treatment efficacy shows in significant interactions between treatment condition and time. Significant overall effects were followed up with contrasts between conditions. All variables were centered for the analysis (32). Significance levels were set at p<.05 (two-tailed). To test whether the 3 treatment conditions led to better outcome than waitlist, linear trends for symptom change over assessments points from baseline to 6 weeks and 14 weeks post-treatment/wait assessments were compared between the 4 trial conditions. To compare the efficacy of the 3 treatment conditions, hierarchical linear modeling compared symptom scores from baseline to the 40-weeks follow-up, fitting linear and quadratic trends for symptom change over the five assessments (pre treatment, 6, 14, 27 and 40 weeks). Interactions of site, sex, medication status, and trauma type with condition and time were explored in additional analyses, but as effects were far from significant, these were omitted from the final models.

For comparison with meta-analyses, we also report effect sizes Cohen’s d (33) for adjusted between-group differences (controlling for pre-treatment scores) and confidence intervals at post-treatment. Effect sizes of 0.5 and above are considered medium effects and those of 0.8 and above large effects. To compare the speed of recovery between the treated groups, a further analysis compared symptom scores on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, and Beck Anxiety and Depression Inventories at 3 weeks for the treated groups, controlling for initial symptom severity. Effect sizes for within-group changes in symptom scores between the pre- and post-treatment/wait assessments were calculated as Cohen’s d statistic (33), using the pooled standard deviation as reference, which is more conservative in estimating improvement than using pre-treatment standard deviations.

Recovery from PTSD diagnosis according to the CAPS was coded if the patient no longer met the minimum number of symptoms in each symptom cluster required by DSM-IV with a score of at least “1” for both frequency and intensity, and a global severity score of at least “2”, as in (9-11). This was determined for all randomly assigned participants. The status of a few subjects with missing CAPS observations was based on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (if available for this time-point) or the last available value on the CAPS. In addition, for comparisons with other papers (21), we calculated the percentages of patients who were totally remitted according to assessor ratings and self-report, using cut-offs recommended in the respective manual, (1) a CAPS score of below 20 (“asymptomatic”), and (2) a Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale score below 11. PTSD symptom deterioration was defined using established cut-offs for statistically reliable change, i.e. increases in symptoms greater than 6.15 on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (34) and increases greater than 10 on the CAPS (21).

Sample size was determined by power analysis on the basis of effect sizes for cognitive therapy observed in previous trials. A group size of n=30 per condition yields 85% power for ES=0.8.

Results

Adverse Effects, Dropouts and Symptom Deterioration

No adverse effects (i.e., negative reactions to treatment procedures such as significant increases in dissociation, suicidal intent or hyperarousal) were reported in any of the groups. Dropouts were defined as attending fewer than 8 sessions (35), unless the earlier completion was agreed with the therapist. Dropout rates were low and did not differ between conditions (Table 2). Only one patient in the supportive therapy group reported symptom deterioration on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Table 2). On the CAPS, fewer patients treated with intensive and cognitive therapy were rated as having deteriorated than those in the waitlist condition. The supportive therapy group did not statistically differ from the other groups.

TABLE 2. Dichotomous Measures of Response to Treatment.

| Variable | 1) Intensive Cognitive Therapy (N = 30) | 2) Standard Cognitive Therapy (N = 31) | 3) Supportive Therapy (N= 30) | 4) Waitlist (N = 30) | Statistical Group Comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ 2 | df | Significant contrasts | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Dropouts | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 3.2 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.26 | 3,121 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Symptom Deterioration | |||||||||||

| Self-reports (PDS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3.06 | 3,121 | |

| Assessor-rated (CAPS) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 3 | 10.0 | 6 | 20.0 | 9.31* | 3,121 | 1,2 < 4 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Loss of Diagnosis (CAPS) | |||||||||||

| Post-treatment or wait (14 weeks) | 22 | 73.3 | 24 | 77.4 | 13 | 43.3 | 2 | 6.7 | 38.92*** | 3,121 | 1,2 >3 > 4 |

| Follow-up 1 (27 weeks) | 22 | 73.3 | 23 | 74.2 | 11 | 36.7 | N/A | 11.70** | 2,91 | 1,2 > 3 | |

| Follow-up 2 (40 weeks) | 20 | 66.7 | 23 | 74.2 | 12 | 40.0 | N/A | 8.18* | 2,91 | 1,2 > 3 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Total Remission (assessor-rated, CAPS) | |||||||||||

| Post-treatment or wait (14 weeks) | 14 | 46.7 | 16 | 51.6 | 6 | 20.0 | 1 | 3.3 | 22.19*** | 3,121 | 1,2 > 3 > 4 |

| Follow-up 1 (27 weeks) | 12 | 40.0 | 21 | 67.7 | 5 | 16.7 | N/A | 16.41*** | 2, 91 | 1 > 2 > 3 | |

| Follow-up 2 (40 weeks) | 16 | 53.3 | 23 | 74.2 | 8 | 26.7 | N/A | 13.84** | 2, 91 | 1,2 > 3 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Total Remission (self-report, PDS) | |||||||||||

| Post-treatment or wait (14 weeks) | 17 | 56.7 | 20 | 64.5 | 9 | 30.0 | 1 | 3.3 | 29.53*** | 3,121 | 1,2 > 3 > 4 |

| Follow-up 1 (27 weeks) | 15 | 50.0 | 22 | 71.0 | 7 | 23.3 | N/A | 13.90** | 2, 91 | 1,2 > 3 | |

| Follow-up 2 (40 weeks) | 17 | 56.7 | 18 | 58.1 | 9 | 30.0 | N/A | 6.05* | 2, 91 | 1,2 > 3 | |

CAPS = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; PDS = Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; n.s. = nonsignificant; N/A: = not applicable:

p < .001;

p < .01,

p < .05

Comparison of Treatment Conditions with Waitlist

Table 2 shows the recovery rates for the treatment and wait conditions. All treatment conditions were more likely to lead to recovery from PTSD diagnosis than waitlist. Intensive and standard cognitive therapy had excellent number-needed-to-treat statistics of 1.50 (95%CI 1.18; 2.06) and 1.41 (95%CI 1.14; 1.87). For supportive therapy, the number-needed-to-treat was 2.73 (95%CI 1.77; 5.95). Similar results were obtained for assessor-rated and self-reported total remission. Table 3 shows the results for the continuous outcome measures. There were significant condition × time interactions (all p<.002) for all primary and secondary outcome measures, PTSD symptoms: CAPS F(3,135.35)=21.50 and Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale F(3,106.56)=21.16; disability F(3,109.86)=14.01; anxiety F(3,106.85)=13.57; depression F(3,122.20)=5.16; quality of life F(3,106.85)=6.96. All contrasts between treatment conditions and waitlist were significant, indicating greater improvement for intensive and standard cognitive therapy and supportive therapy compared to waitlist, except for a nonsignificant difference between supportive therapy and waitlist on quality of life. As shown in Table 4, pre-post effect sizes d for both intensive and standard cognitive therapy showed very large improvement in PTSD symptoms and disability, and large improvement in anxiety, depression, and quality of life.

TABLE 3. Intent-to-Treat Results for Continuous Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures.

| Measure | Intensive Cognitive Therapy (N=30) | Standard Cognitive Therapy (N=31) | Supportive Therapy (N=30) | Waitlist (N=30) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

|

| ||||||||

| Primary Outcomes: PTSD symptoms | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Independent Assessor (CAPS) | ||||||||

| Pre-Treatment or Wait | 78.72 | 19.80 | 70.60 | 13.45 | 74.60 | 15.39 | 69.95 | 14.17 |

| 14 weeks (Post) | 32.22 | 27.20 | 26.97 | 28.68 | 47.88 | 31.77 | 65.28 | 20.64 |

| 27 weeks (Follow-up 1) | 35.56 | 26.26 | 20.86 | 25.23 | 49.32 | 32.46 | ||

| 40 weeks (Follow-up 2) | 35.33 | 35.11 | 20.96 | 27.71 | 49.04 | 38.01 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Self-Report (PDS) | ||||||||

| Pre-Treatment or Wait | 33.21 | 7.66 | 32.44 | 6.94 | 34.26 | 7.40 | 32.46 | 7.60 |

| 6 weeks | 14.85 | 8.92 | 16.33 | 11.58 | 23.30 | 12.90 | 31.92 | 6.84 |

| 14 weeks (Post) | 11.98 | 9.60 | 9.39 | 10.88 | 19.98 | 13.67 | 29.24 | 9.36 |

| 27 weeks (Follow-up 1) | 13.91 | 11.63 | 10.15 | 11.86 | 18.93 | 12.98 | ||

| 40 weeks (Follow-up 2) | 13.03 | 13.99 | 9.63 | 11.26 | 20.94 | 15.40 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Secondary Outcome M easures: Disability, Depression, Anxiety, Quality of Life | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Disability (SDS) | ||||||||

| Pre-Treatment or Wait | 20.48 | 5.55 | 21.39 | 5.11 | 19.65 | 6.97 | 17.28 | 7.74 |

| 6 weeks | 10.72 | 7.51 | 14.02 | 9.35 | 16.60 | 7.90 | 17.22 | 6.67 |

| 14 weeks (Post) | 9.30 | 8.20 | 10.02 | 9.76 | 14.28 | 9.09 | 17.20 | 6.38 |

| 27 weeks (Follow-up 1) | 10.61 | 8.80 | 8.68 | 9.50 | 13.67 | 9.86 | ||

| 40 weeks (Follow-up 2) | 9.72 | 9.22 | 9.37 | 10.07 | 14.47 | 11.35 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Anxiety (BAI) | ||||||||

| Pre-Treatment or Wait | 26.23 | 13.12 | 28.42 | 14.17 | 25.12 | 11.31 | 23.57 | 9.12 |

| 6 weeks | 13.55 | 12.16 | 13.88 | 14.01 | 17.01 | 13.30 | 23.26 | 10.88 |

| 14 weeks (Post) | 11.57 | 11.94 | 9.24 | 12.09 | 16.35 | 14.56 | 22.13 | 10.59 |

| 27 weeks (Follow-up 1) | 10.37 | 11.59 | 9.63 | 13.71 | 15.50 | 13.74 | ||

| 40 weeks (Follow-up 2) | 11.85 | 13.35 | 9.00 | 12.61 | 15.99 | 16.15 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Depression (BDI) | ||||||||

| Pre-Treatment or Wait | 23.93 | 9.86 | 21.90 | 10.77 | 26.18 | 10.68 | 23.47 | 8.96 |

| 6 weeks | 14.34 | 9.30 | 13.39 | 10.70 | 19.79 | 12.42 | 21.26 | 8.06 |

| 14 weeks (Post) | 12.10 | 9.97 | 11.07 | 11.80 | 17.00 | 12.82 | 20.85 | 10.02 |

| 27 weeks (Follow-up 1) | 12.03 | 11.25 | 10.54 | 12.70 | 16.29 | 12.10 | ||

| 40 weeks (Follow-up 2) | 12.84 | 12.54 | 9.44 | 12.18 | 18.60 | 14.05 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Quality of Life | ||||||||

| Pre-Treatment or Wait | 36.93 | 12.84 | 39.36 | 21.87 | 38.78 | 18.40 | 45.68 | 20.98 |

| 6 weeks | 49.54 | 17.23 | 57.49 | 20.82 | 44.86 | 25.25 | 41.74 | 15.13 |

| 14 weeks (Post) | 52.67 | 20.21 | 62.93 | 21.70 | 49.22 | 24.97 | 46.75 | 19.00 |

| 27 weeks (Follow-up 1) | 58.10 | 22.78 | 60.43 | 23.31 | 49.61 | 25.67 | ||

| 40 weeks (Follow-up 2) | 54.57 | 20.74 | 65.11 | 22.46 | 50.38 | 25.53 | ||

CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PDS = Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; N/A = not assessed;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

TABLE 4. Within and Between Group Effect Sizes Cohen’s d at the 14-Week Assessment (Post Treatment/Wait) and Adjusted Intent-to-Treat Group Differences (95% Confidence Intervals).

| Intensive Cognitive Therapy | Standard Weekly Cognitive Therapy | Supportive Therapy | Waitlist | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Comparison | Measure | Adjusted Difference | 95% CI | da | Adjusted Difference | 95% CI | da | Adjusted Difference | 95% CI | d | da |

|

| |||||||||||

| Within-group Pre-Post Effect Sizes | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| PTSD symptoms (CAPS) | 1.95 | 1.95 | 1.07 | 0.26 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms (PDS) | 2.45 | 2.53 | 1.30 | 0.38 | |||||||

| Disability | 1.60 | 1.50 | 0.66 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Anxiety | 1.17 | 1.46 | 0.67 | 0.15 | |||||||

| Depression | 1.19 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 0.28 | |||||||

| Quality of Life | 0.93 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 0.05 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Between-Group Effect Sizes | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Waitlist Compared to … | PTSD symptoms (CAPS) | 39.55*** | 26.60; 52.51 | 1.57 | 38.80*** | 26.19; 51.40 | 1.55 | 20.84** | 8.06; 33.61 | 0.84 | |

| PTSD symptoms (PDS) | 17 72*** | 12.54; 22.90 | 1.75 | 19.84*** | 14.71; 24.97 | 1.96 | 10.35*** | 5.15; 15.54 | 1.02 | ||

| Disability | 9.96*** | 6.10; 13.81 | 1.33 | 9.82*** | 5.95; 13.68 | 1.30 | 4.45* | 0.62; 8.28 | 0.59 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Waitlist Compared to … | PTSD symptoms (CAPS) | 39.55*** | 26.60; 52.51 | 1.57 | 38.80*** | 26.19; 51.40 | 1.55 | 20.84** | 8.06; 33.61 | 0.84 | |

| PTSD symptoms (PDS) | 17 72*** | 12.54; 22.90 | 1.75 | 19.84*** | 14.71; 24.97 | 1.96 | 10.35*** | 5.15; 15.54 | 1.02 | ||

| Disability | 9.96*** | 6.10; 13.81 | 1.33 | 9.82*** | 5.95; 13.68 | 1.30 | 4.45* | 0.62; 8.28 | 0.59 | ||

| Anxiety | 11.98*** | 6.54; 17.43 | 1.13 | 15.48*** | 10.04; 20.91 | 1.45 | 6.61* | 1.18; 12.05 | 0.62 | ||

| Depression | 9.04*** | 4.26; 13.81 | 0.97 | 8.81*** | 4.06; 13.55 | 0.95 | 5.54* | 0.75; 10.34 | 0.59 | ||

| Quality of Life | −12.43** | −21.28; −3.58 | 0.73 | −20.67*** | −29.39;−11.95 | 1.21 | −7.98 | −16.79; 0.83 | 0.47 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Supportive Therapy Compared to… | PTSD symptoms (CAPS) | 18.72** | 5.96; 31.45 | 0.75 | 17.96** | 5.31; 30.62 | 0.72 | ||||

| PTSD symptoms (PDS) | 7.37** | 2.19; 12.55 | 0.73 | 9.49*** | 4.34; 14.64 | 0.94 | |||||

| Disability | 5.51** | 1.71; 9.31 | 0.74 | 5.37** | 1.59; 9.15 | 0.72 | |||||

| Anxiety | 5.37* | 0.06; 10.80 | 0.51 | 8.86** | 3.46; 14.27 | 0.83 | |||||

| Depression | 3.49 | −1.30; 8.28 | 0.37 | 3.26 | − 1.50; 8.05 | 0.35 | |||||

| Quality of Life | −4.45 | −13.17; 4.28 | 0.26 | −12.69** | −21.33; −4.04 | 0.74 | |||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Standard Weekly Cognitive Therapy compared to … | PTSD symptoms (CAPS) | 0.76 | −12.06; 13.57 | 0.03 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms (PDS) | −2.12 | −7.26; 3.02 | 0.21 | ||||||||

| Disability | 0.14 | −3.63; 3.91 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Anxiety | −3.49 | −8.89; 1.90 | |||||||||

| Depression | 0.23 | −4.52; 4.98 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Quality of Life | 8.24 | −0.42; 16.90 | 0.48 | ||||||||

based on pooled standard deviation

CAPS= Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; PDS= Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale.

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Comparison of Treatment Conditions

At the post-treatment and follow-up assessments, more patients receiving intensive and standard cognitive therapy had recovered from a PTSD diagnosis than those receiving supportive therapy (Table 2). Similar results were obtained for assessor-rated and self-reported total remission. For all primary and secondary continuous outcomes except for depression (Table 3), hierarchical linear modeling showed significant interactions between condition and linear time effects; PTSD symptoms: CAPS F(2,154.13)=7.83, p=.001, and Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale F(2,215.14)=4.42, p=.01; disability F(2,220.14)=7.45, p=.001; anxiety F(2,176.80)=5.40, p=.005; depression F(2,213.98)=0.79, p>.23; quality of life F(2, 231.98)=3.27, p=.04. Contrasts showed that both intensive and standard cognitive therapy led to greater improvement than supportive therapy on the primary outcome measures (CAPS, Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale), disability and anxiety. For quality of life, standard cognitive therapy was superior to supportive therapy, and there was a trend for intensive cognitive therapy to be superior (p<.10). Baseline-adjusted mean group differences at post-treatment and effect sizes are shown in Table 4.

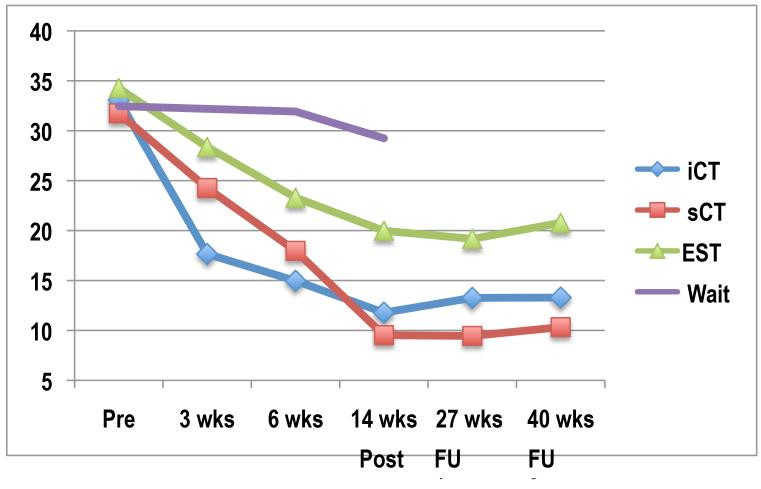

Speed of Recovery

Comparison of the treatment groups at 3 weeks, controlling for initial severity, showed significant differences on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, F(2,87)=10.35, p<.001; anxiety, F(2,87)=4.23, p=.018; and depression, F(2, 87)=5.27, p=.007. The intensive cognitive therapy group scored lower on PTSD symptoms than the standard cognitive therapy and supportive therapy groups, baseline-adjusted means 16.65 (95%CI 13.19; 20.12), 24.05 (95%CI 20.64; 27.46), 27.65 (95%CI 24.18; 31.12), respectively. They also had lower depression scores at 3 weeks than both other treatment groups, and lower anxiety scores than supportive therapy.

Additional Comparison of Intensive and Standard Weekly Cognitive Therapy Including Post-Wait Patients

To further test the comparability of outcomes between the intensive and standard cognitive therapy groups, waitlist patients who still had PTSD at the post-wait assessment and still wished treatment were randomly assigned to either standard (n=13) or intensive (n=11) cognitive therapy. The comparison of all patients treated with intensive (n=41) and standard cognitive therapy (n=44) had 80% power in detecting a difference of 4.4 points on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. There were no interactions between treatment condition and time on any measure, indicating comparable outcomes. Baseline-adjusted differences at 14 weeks between all standard weekly and intensive cognitive therapy patients were: CAPS −2.19 (95%CI −12.97;8.60), d=0.08, and Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale −1.48 (95%CI −5.35;2.39), d=0.15; disability 0.51 (95%CI −2.74;3.75), d=0.06; anxiety −2.59 (95%CI −6.79;1.63), d=0.24; depression 0.27 (95%CI −3.59;4.13), d=0.03; quality of life 4.8(95%CI −3.18;12.72), d=0.23.

Discussion

The main findings were (1) that a novel 7-day intensive version of cognitive therapy for PTSD was well tolerated, achieved faster symptom reduction and led to comparable overall outcomes as standard once-weekly cognitive therapy delivered over three months, and (2) that both intensive and standard cognitive therapy had specific effects and were more efficacious in treating PTSD than emotion-focused supportive therapy. The intent-to-treat pre-post effect sizes for improvement in PTSD symptoms with both intensive and standard cognitive therapy were very large, and patients’ mean scores after treatment were in the nonclinical range. There were no site effects, suggesting that the treatment worked as well in patients recruited from a routine clinical setting as in those referred to a research clinic. The study replicated the excellent outcomes observed for cognitive therapy for PTSD in previous trials (9-10), and is the first study to demonstrate that this treatment not only leads to a large reductions in symptoms of PTSD, disability, anxiety and depression, but also to large increases in quality of life.

Some authors have expressed concerns about a risk of symptom exacerbation with trauma-focused psychological treatments (6-7), and it is therefore noteworthy that both standard and intensive cognitive therapy were well tolerated, in line with initial case reports of intensive trauma-focused treatments (8, 36). Delivering cognitive therapy in an intensive format did not increase dropout rates or symptom deterioration. Both the standard and intensive cognitive therapy groups were less likely to be rated as having deteriorated on the CAPS than those waiting for treatment. The present study thus underlines the safety of this treatment approach. The feasibility of intensive cognitive therapy is of interest for therapeutic settings where treatment needs to be conducted over a short period of time, such as residential therapy units or occupational groups exposed to trauma, or where patients have to get better quickly to avoid secondary complications such as job loss or marital problems. The feasibility of intensive treatment is also of interest for patient choice, as some patients may find a shorter condensed treatment preferable.

The novel intensive version of cognitive therapy for PTSD may offer some advantages over weekly treatment. Problems with concentration and memory are common in PTSD, and the intensive format may help keep the therapeutic material fresh in patients’ minds until the next session. A possible disadvantage for some patients is that the intensive treatment phase offers less opportunity for the therapist to guide them to reclaim their lives through homework assignments.

Emotion-focused supportive therapy led to greater improvement than waiting for treatment, and a substantial minority of 43% patients no longer met criteria for PTSD after therapy. Supportive therapy was included as a credible therapeutic alternative so that observed effects of cognitive therapy could be attributed to its specific effects beyond the benefits of good therapy. Emotion-focused supportive therapy is a plausible treatment for PTSD as the disorder is characterized by high levels of emotional distress, and poor social support has been shown to contribute to the prediction of PTSD (37). Patients’ ratings of credibility and therapeutic alliance were the same as for cognitive therapy. Supportive therapy led to similar improvements as cognitive therapy in depression, but importantly led to substantially less improvement in PTSD symptoms, disability, anxiety and quality of life, indicating specific treatment effects of cognitive therapy. Mean scores on the primary outcome measures were still within the clinical range post supportive therapy, whereas patients treated with standard or intensive cognitive therapy had mean scores in the nonclinical range. Thus, supportive therapy is not as effective as cognitive therapy in treating PTSD, but has benefits for some patients. The pattern of results is consistent with studies that compared other forms of trauma-focused psychological treatments with active nondirective treatments (20-21, 38-39).

This study had some limitations. First, although the observed differences between intensive and standard cognitive therapy were small and nonsignificant, it is conceivable that statistically significant differences could be discovered in larger trials. However, it is debatable whether such small differences would be clinically meaningful. Second, the study focused on traumatic events in adulthood, and it will need to be investigated whether the results generalize the treatment of childhood trauma.

Patient Perspective.

Ms D, age 29, developed posttraumatic stress disorder after a life-threatening medical emergency. The trauma happened three years before she participated in the trial.

I sought treatment because I knew I wasn't dealing well with the after-effects of my trauma. I didn't feel like I was living; only existing. You see, during my trauma, I had physical injuries and my legs had to be amputated below the knees. Afterwards, I felt like my life was over.

I found all of the therapy helpful. Especially going over my memories and making sense of them logically, with the benefit of hindsight and realism. I also found the homework essential to my recovery. I looked forward to the 'me' time completing it.

At the end of the treatment, I felt so much better! My whole attitude to life had transformed and I looked forward to every new day. Also, my symptoms had dramatically reduced. I still thought of some of the memories (not in a 'flashback' sense), but they no longer caused me to cry.

Now, 3 years later, my life is very different. I feel totally reconciled to the person I was PRE-trauma. I don’t find those memories from the past as painful anymore. I can safely say that I am indeed living, not just existing anymore. My experience of cognitive therapy was life changing and I'm very grateful for it.

Figure 2.

Changes in PTSD symptoms as measured with the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale for 7-day intensive cognitive therapy (iCT, all patients), standard weekly cognitive therapy (sCT, all patients), weekly emotion-focused supportive therapy (EST) and wait list. All patients completed the scale at the pre treatment/wait, 6 weeks (6wks) and 14 weeks (post treatment/wait, 14 wks). Patients receiving therapy also completed the scale at 3 weeks (3wks), 27 weeks (Follow-up 1, FU1) and 40 weeks (Follow-up 2, FU2).

Disclosures and acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant 069777 to Anke Ehlers and David Clark). The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests. We would like thank Kelly Archer, Anna Bevan, Francesca Brady, Ruth Collins, Linda Horrell, Judith Kalthoff, and Catherine Seaman for their help with trial administration, data collection, entry and analysis, Margaret Dakin, Sue Helen and Julie Twomey for administrative support, Dirk Hillebrandt for statistical consultation, Louise Waddington and Ruth Collins for ratings of treatment sessions, and Michelle Moulds for therapist training.

Footnotes

The trial was registered as ISRCTN 48524925.

References

- 1.Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E, Dutra L, Westen D. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:214–217. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisson JI, Ehlers A, Matthews R, Pilling S, Richards D, Turner S. Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:97–104. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cloitre M. Effective psychotherapies for posttraumatic stress disorder: a review and critique. CNS Spectrums. 2009;14(suppl 1):32–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Öst LG. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramowitz JS, Foa EB, Franklin ME. Exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: effectiveness of intensive versus twice-weekly treatment sessions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:394–398. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarrier N, Pilgrim H, Sommerfield C, Fragher B, Reynolds M, Graham E, Barrowclough C. A randomized trial of cognitive therapy and imaginal exposure in the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;69:13–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilpatrick DG, Best CL. Some cautionary remarks on treating sexual assault victims with implosion. Behav Ther. 1984;15:421–423. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, Grey N, Wild J, Liness S, Manley J, Waddington L, McManus F. Intensive Cognitive Therapy for PTSD: A feasibility study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38:383–398. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell M, Herbert C, Mayou R. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy, self-help booklet, and repeated early assessment as early interventions for PTSD. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1024–1032. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell M. Cognitive therapy for PTSD: development and evaluation. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespie K, Duffy M, Hackmann A, Clark DM. Community based cognitive therapy in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder following the Omagh bomb. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith P, Yule W, Perrin S, Tranah T, Dalgleish T, Clark DM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD in children and adolescents: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1051–1061. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318067e288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy M, Gillespie K, Clark DM. Post-traumatic stress disorder in the context of terrorism and other civil conflict in Northern Ireland: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007 doi: 10.1136/bmj.39021.846852.BE. doi:10.1136/bmj.39021.846852.BE (published 11 May) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) Biometrics Research Department of the New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pocock S. Clinical trials. A practical approach. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agnew-Davies R, Stiles W. Alliance structure assessed by the Agnew Relationship Measure. Br J Clin Psychol. 1998;37:155–172. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1998.tb01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell M, Grey N. Cognitive Therapy for PTSD: a therapist’s guide. Oxford University Press; Oxford: in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Guthrie RM, Dang ST, Nixon RDV. Imaginal exposure alone and imaginal exposure with cognitive restructuring in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:706–712. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Engel CC, Foa EB, Shea MT, Chow BK, Resick PA, Thurston V, Orsillo SM, Haug R, Turner C, Bernardy N. Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;28:820–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychol Assessment. 1997;9:445–451. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association . Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, Endicott J. Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1171–1178. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1171. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackburn IM, James IA, Milne DL, Baker C, Standart S, Garland MA, Reichelt FK. The revised Cognitive Therapy Scale (CTS-R): Psychometric properties. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:431–446. 201. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patterson CH. The therapeutic relationship. Brooks/Cole; Monterey, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heck RH, Thomas SL, Tabata LN. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling with SPSS. Routledge; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CC, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;10:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hilsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foa EB, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC, Hembree EA, Alvarez-Conrad J. Does imaginal exposure exacerbate PTSD symptoms? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:1022–1028. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute of Clinical Excellence . Clinical guideline 26: Posttraumatic stress disorder: The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; London, UK: 2005. http://guidance.nice.org/CG26 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendriks L, de Kleine R, van Rees M, Bult C, van Minnen A. Feasibility of brief intensive exposure therapy for PTSD with childhood sexual abuse: a brief clinical report. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2010;1:5626. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v1i0.5626. DOI: 10.3402/ejpt.v1i0.5626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Devineni T, Veazey CH, Galovski TE, Mundy E, Buckley TC. A controlled evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress in motor vehicle accident survivors. Behav Res Ther. 2003;421:79–96. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehlers A, Bisson J, Clark DM, Creamer M, Pilling S, Richards S, Schnurr P, Turner S, Yule W. Do all psychological treatments really work the same in posttraumatic stress disorder? Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.001. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]