Abstract

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is an EBV associated cancer that is highly treatable when diagnosed early, with 5-year disease-free survival of ~90%. However, NPC is typically diagnosed at advanced stages, where disease-free survival is <50%. There is therefore a need for clinical tools to assist in early NPC detection, particularly in high-risk individuals.

Methods

We evaluated the ability of anti-EBV IgA antibodies to detect incident NPC among high-risk Taiwanese individuals. NPC cases (N=21) and age and sex-matched controls (N=84) were selected. Serum collected prior to NPC diagnosis was tested for ELISA-based IgA markers against the following EBV peptides: EBNA1, VCAp18, EAp138, Ead_p47, and VCAp18 + EBNA1 peptide mixture. The sensitivity, specificity, and screening program parameters were calculated.

Results

EBNA1 IgA had the best performance characteristics. At an optimized threshold value, EBNA1 IgA measured at baseline identified 80% of the high-risk individuals who developed NPC during follow-up (80% sensitivity). However, approximately 40% of high-risk individuals who did not develop NPC also tested positive (false positives). Application of EBNA1 IgA as a biomarker to detect incident NPC in a previously unscreened, high-risk population revealed that 164 individuals needed to be screened to detect 1 NPC and that 69 individuals tested positive per case detected.

Conclusions

EBNA1 IgA proved to be a sensitive biomarker for identifying incident NPC, but future work is warranted to develop more specific screening tools to decrease the number of false positives.

Impact

Results from this study could inform decisions regarding screening biomarkers and referral thresholds for future NPC early-detection program evaluations.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, EBV serology, familial NPC, cancer screening

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) proteins play an established, necessary role in the etiology and pathogenesis of NPC, [1–10] and evidence from recent, prospective studies has demonstrated that higher antibody levels, particularly IgA antibodies directed against lytic and latent protein expression in epithelial cells, precede the development of NPC. [11–13] Men from the general Taiwanese population who tested positive for IgA antibodies against the lytic viral capsid antigen (VCA) protein had an increased risk of developing NPC compared to VCA IgA negative men, an association that persisted even ≥5 years after antibody measurement (HR=13.9; 95% CI 3.1–61.7). [11]

This association between altered EBV serology and NPC development has also been reported among Taiwanese individuals with an inherently elevated NPC risk. In individuals from multiplex NPC families, families with ≥1 first or second degree relatives affected by NPC, the incidence of disease is reported to be 90 × 105, 10-fold higher than the general Taiwanese population. [14] Even among this group, elevated antibody titers of both VCA IgA and IgA antibodies against the latent EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) protein prior to NPC diagnosis were associated with higher rates of NPC, with EBNA1 IgA positive individuals having >6-fold increased risk compared to EBNA1 IgA negative individuals (RR=6.6; 1.5–61). [14]

Although the association of EBNA1 and VCA IgA with NPC risk has been established, the important question of whether antibody patterns can discriminate between individuals who will or will not develop NPC in the future (i.e. clinical utility) remains inadequately answered. In the prospective evaluation of anti-EBV antibodies and NPC risk among high-risk family members in Taiwan that utilized research-based assays for EBNA1 and VCA IgA, these two markers proved to be sensitive for detecting incident NPC but did not achieve specificity above approximately 50% for either marker. [14]

To move the use of EBV serology towards a clinically applicable tool for screening or management of individuals at high-risk for NPC, we previously evaluated and reported the reproducibility of a panel of chemically-defined, peptide-based anti-EBV antibodies. [15] The IgA antibodies on this panel proved to have acceptable performance characteristics, providing a reproducible EBV serology panel for application in future studies.

We selected IgA antibodies from this panel with ≥70% intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), a measure of the proportion of the total assay variability attributed to true variability in IgA antibody levels between individuals. Using these IgA antibodies, we evaluated whether EBV serology measured years prior to disease presentation could be used to identify high-risk individuals in this specific Taiwanese subpopulation who developed NPC over time. We also simulated the application of the best-performing IgA marker on this panel as a screening tool for NPC in this high-risk population and report the approximate number of individuals that would need to be screened per case of NPC detected under varying, realistic screening program parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

High-risk individuals for this study were selected from an ongoing NPC multiplex family study in Taiwan. Details of this study population have been published previously. [14, 16, 17] In brief, 2,557 unaffected family members recruited from 358 multiplex families had blood drawn and have been followed since 1996 for the development of incident NPC. Ascertainment of NPC is determined through both linkage to the Taiwan National Cancer Registry and active clinical evaluation of a substantive portion of the cohort at a follow-up visit.

All NPC cases ascertained through December 31, 2010 were selected for this study (N=21). For each of the 21 incident NPC cases, 4 individuals from this high-risk population who did not develop NPC were selected, matched on both gender and age (5-year intervals), resulting in 84 controls. Cases and controls were not matched on family so that findings could be applied broadly to multiplex families.

Blood was drawn at study enrollment for each of these 105 individuals. Serum from the blood collection was tested for IgA antibodies against the following EBV proteins according to previously published protocols: [15] VCAp18, EBNA1, EAp138, Ead_p47, and a combined mixture of VCAp18 + EBNA1 peptides. [18] The ELISA assays used were chemically defined (e.g. peptides) rather than recombinant or cell-based antigens, facilitating standardization that would be important for future clinical utility. In each ELISA test, two known EBV IgG/IgA positive reference sera were tested at 1:100 in duplicate calibrators, and the cutoff value (COV) for each ELISA plate was defined by calculating the mean OD450 reactivity + 2 times the standard deviation (SD) of 4 defined EBV-negative sera (1:100) tested in duplicate. Results were reported as the mean of the duplicate absorbance value observed for each IgA antibody, divided by the COV.

To ensure that the performance characteristics of the peptide-based anti-EBV antibody assays measured in this set of samples fell within the reported reproducibility values previously published, [15] 29 individuals had duplicate samples included in the testing (12 across plate and 17 within plate). Coefficients of variation (CVs) and ICCs were calculated for each anti-EBV IgA antibody in the panel utilizing PROC GLM (SAS version 9.3, Cary, NC).

The percentage of incident NPC cases and unaffected high-risk individuals who tested positive at a standardized threshold value (≥1.0) was calculated. To ensure that these IgA antibodies measured prior to diagnosis were valid for predicting the development of future disease, blood drawn after NPC diagnosis for 142 prevalent NPC cases (67 early stage and 75 late stage) and 75 controls from the general Taiwanese population recruited in a previous case-control study [19] were also tested for the presence of these 5 anti-EBV IgA antibodies at the same threshold value (≥1.0). If levels of these IgA markers measured prior to diagnosis were hypothesized to predict future disease, we expected to observe a high prevalence above the threshold in samples taken concurrent to the time of NPC diagnosis. Furthermore, we expected that the percentage above the threshold should be lower among population controls with low risk for NPC.

We calculated a delta statistic for each respective anti-EBV serological marker, defined as the difference in the mean IgA antibody level between cases and controls, divided by the variance in this population. According to the method published by Wentzensen and Wacholder, [20] this delta statistic is a measure of a potential screening tool’s ability to discriminate between cases and non-cases and can be used to generate a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to illustrate the performance characteristics for the screening marker being evaluated at different threshold values.

The delta statistics were calculated for each of the 5 anti-EBV IgA antibodies evaluated in this study, and the optimal threshold value for a given IgA marker was defined as the value on the ROC curve with the highest specificity that successfully identified at least 80% of incident NPC cases (80% sensitivity) in this high-risk population. We also identified an alternative threshold with the highest specificity that maintained at least 90% sensitivity.

For the IgA marker on this panel with the highest delta statistic, or greatest ability to discriminate between high-risk individuals who would or would not go on to develop NPC, we further estimated two screening parameters: 1) the number of high-risk individuals needed to be screened to detect 1 NPC case, and 2) the number of high-risk individuals with IgA levels above the threshold (test positives) for each NPC case detected. The number of high-risk individuals needed to be screened for each detected NPC case is equivalent to the inverse of the probability of detecting NPC using a given IgA marker in this high-risk population: ( ). The number of high-risk individuals testing positive for each detected NPC case is equivalent to the inverse of the probability of detecting NPC among the test positives, or the inverse of the positive predictive value of a given IgA marker: ( ). Finally, these two screening parameters were also estimated assuming application of the less specific IgA markers on the panel to this high-risk population.

RESULTS

The average duration of follow-up between baseline blood draw and diagnosis among the 21 incident NPC cases was 5.4 years (SD=3.0 years; median=4.9 years). The coefficient of variation (CV) and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for VCAp18 IgA, EBNA1 IgA, EAp138 IgA, and Ead_p47 IgA measured in these 105 individuals were consistent with values previously reported. [15] The mixture of VCAp18 + EBNA1 IgA peptides that was introduced to the panel for the first time in this study had a CV of approximately 10% and an ICC >90%, consistent with the premise that the variability in this particular IgA marker between samples was due to true differences between individuals rather than assay variability.

Utilizing a threshold of ≥1.0, the percentage of individuals with blood drawn at the time of NPC diagnosis (i.e. prevalent NPC) with a positive result exceeded 90% for both EBNA1 IgA and the combined VCAp18 + EBNA1 IgA markers. (Table 1) In contrast, less than half of the prevalent NPC cases tested above the threshold for either early antigen (EA) IgA antibody, although both EAp138 IgA and Ead_p47 IgA were highly specific markers, testing above the threshold is <20% of general population controls. Importantly, EBNA1 IgA, in addition to being very sensitive, had a specificity of 80% and proved to be the EBV serological marker with the best performance characteristics for prevalent NPC.

Table 1.

Sensitivity and Specificity for anti-EBV IgA antibodies, applied to prevalent NPC and healthy controls from Taiwan

| IgA Marker | Sensitivity for Prevalent NPC a | Specificity in healthy, community controls |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Capsid Antigen (VCAp18) | 78.9 | 49.3 |

| Early Prevalent Disease | 76.1 | |

| Late Prevalent Disease | 81.3 | |

| Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen (EBNA1) | 92.3 | 80.0 |

| Early Prevalent Disease | 95.5 | |

| Late Prevalent Disease | 89.3 | |

| Early Antigen (Ead_p47) | 43.0 | 81.3 |

| Early Prevalent Disease | 38.8 | |

| Late Prevalent Disease | 46.7 | |

| Early Antigen (EAp138) | 47.9 | 82.7 |

| Early Prevalent Disease | 38.8 | |

| Late Prevalent Disease | 56.0 | |

| Combined VCAp18 + EBNA1 ELISA | 99.3 | 32.0 |

| Early Prevalent Disease | 100 | |

| Late Prevalent Disease | 98.7 |

For each ELISA test, two known EBV IgG/IgA positive reference sera were tested at 1:100 in duplicate calibrators, and the cutoff value (COV) for each ELISA plate was defined by calculating the mean OD450 reactivity + 3 multiplied by the standard deviation (SD) of 4 defined EBV-negative sera (1:100) tested in duplicate. Raw results were reported as the mean of the duplicate absorbance value observed for each IgA marker, divided by the COV. The percentages in the table above are based on a threshold value for determining a positive result of ≥1.0.

Early Disease: WHO Stage I/II

Late Disease: WHO Stage III/IV

The percentage of high-risk multiplex family members developing NPC during follow-up (i.e. incident NPC) who tested above the ≥1.0 threshold was lower as compared to prevalent NPC cases for each anti-EBV IgA marker evaluated. (Table 2) However, the trends observed were the same as those observed for prevalent disease; EBNA1 IgA still proved to be the best maker for incident NPC.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and Specificity for anti-EBV IgA antibodies, applied to high-risk multiplex family members from Taiwan

| IgA Marker | Sensitivity for Incident NPC a | Specificity in high-risk controls |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Capsid Antigen (VCAp18) | 52.4 | 46.4 |

| Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen (EBNA1) | 66.7 | 85.7 |

| Early Antigen (Ead_p47) | 0.0 | 92.9 |

| Early Antigen (EAp138) | 0.0 | 95.2 |

| Combined VCAp18 + EBNA1 ELISA | 85.7 | 35.7 |

For each ELISA test, two known EBV IgG/IgA positive reference sera were tested at 1:100 in duplicate calibrators, and the cutoff value (COV) for each ELISA plate was defined by calculating the mean OD450 reactivity + 3 multiplied by the standard deviation (SD) of 4 defined EBV-negative sera (1:100) tested in duplicate. Raw results were reported as the mean of the duplicate absorbance value observed for each IgA marker, divided by the COV. The percentages in the table above are based on a threshold value for determining a positive result of ≥1.0.

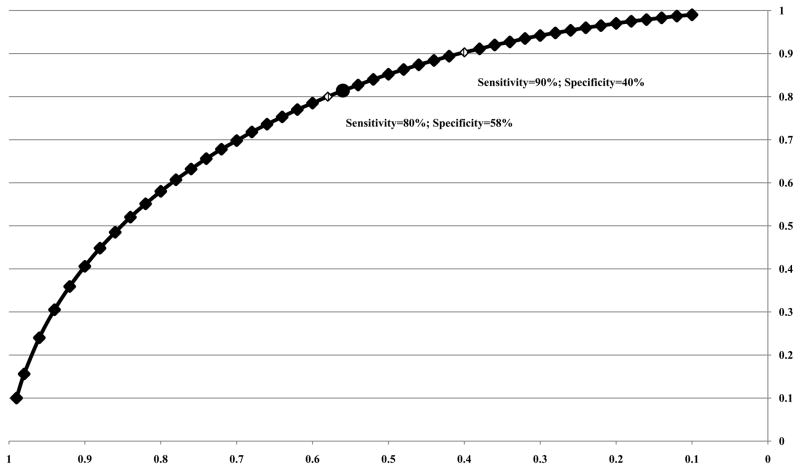

The difference in the mean EBNA1 IgA level measured at baseline in high-risk multiplex family members who developed NPC (mean=2.67) versus those who did not develop NPC (mean=0.91) was used to calculate a delta statistic (Δ=1.04) and generate an ROC curve (Figure 1). [20] The optimized threshold value chosen for EBNA1 IgA (cutoff=0.72) in high-risk multiplex family members had the highest specificity (58%) while still identifying at least 80% of individuals who developed NPC (80% sensitivity). The alternative threshold (cutoff=0.61) that identified 90% of individuals who developed NPC (90% sensitivity) had lower specificity (40%), which was still higher than the specificity of the most sensitive marker on the panel, the combined VCAp18 + EBNA1 IgA peptide mixture.

Figure 1. ROC curve for EBNA1 IgA marker (Δ=1.04).

An optimized threshold value for a given anti-EBV IgA marker was defined as the value on the ROC curve with the highest specificity that successfully identified at least 80% of incident NPC cases (80% sensitivity) in this high-risk population. The alternative threshold had the highest specificity while identifying at least 90% of incident NPC.

The test characteristics of the optimized threshold value for EBNA1 IgA were used, in addition to the 5-year cumulative NPC risk among individuals ≥40 years of age in this target population, [14] to calculate the number of high-risk multiplex family members needed to be screened per NPC case detected (N=164) as well as the number of who tested above the threshold for EBNA1 IgA per NPC case detected (N=69). (Table 3) Application of the more sensitive alternative threshold for classifying individuals as positive for EBNA1 IgA yielded slightly different results: the number of high-risk multiplex family members needed to be screened per NPC case detected was lower (N=146), but the number who tested above the threshold per NPC case detected was higher (N=88). Of note, the percentage of individuals who tested positive (e.g. required additional diagnostic intervention) among those needing to be screened to detect 1 NPC case was higher when the sensitivity increased but specificity decreased (90% sensitivity threshold: 88/146=60%; 80% sensitivity threshold: 69/164 = 42%).

Table 3.

Application of EBNA1 IgA as Screening Tool for Incident NPC in High-risk Multiplex Taiwanese Family Members (40+ years of age)

| Screened Population | 5-year NPC Risk | Sensitivity | Specificity | # Screened per NPC Case c | # Screen Positive per NPC Case d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiwanese Multiplex Family members (40+) | 762 per 100,000 a | 80% b | 58% | 164 | 69 |

| Taiwanese Multiplex Family members (40+) | 762 per 100,000 | 90% e | 40% | 146 | 88 |

11 NPC cases were ascertained among 1,444 high-risk Taiwan Multiplex Family Study participants at least 40 years of age at the time of the baseline blood draw [14]

Sensitivity and Specificity generated from EBNA1 IgA cutoff value = 0.72

# Screened per NPC Case Detected = 1/(Sensitivity * 5-Year NPC Risk)

# Screen Positive per NPC Case Detected = 1/(Positive Predictive Value)

Sensitivity and Specificity generated from EBNA1 IgA cutoff value = 0.61

The VCAp18 IgA and combined VCAp18 + EBNA1 IgA markers, although sensitive, were not highly specific markers in this high-risk multiplex family population, with lower delta statistics than EBNA1 IgA alone (VCAp18: Δ=0.08; VCAp18 + EBNA1: Δ=0.98) illustrating a diminished capacity to distinguish between cases and non-cases. For VCAp18 IgA, the choice of a threshold value with ≥80% sensitivity resulted in a specificity of only 20% (Supplemental Figure 1), less than half the specificity of EBNA1 IgA. For the combined VCAp18 + EBNA1 IgA marker, the specificity for the threshold value with ≥80% sensitivity was 54% (Supplemental Figure 2), which although superior to VCAp18 alone was still slightly inferior to EBNA1 IgA alone. Application of these less specific screening tools to the same unscreened, high-risk population resulted in higher numbers of multiplex family members who tested above the threshold per NPC case detected (VCAp18=128; VCAp18 + EBNA1=75), particularly for VCAp18, where a halving in specificity resulted in nearly double the number of individuals requiring additional diagnostic workup despite not developing NPC for each true NPC case detected. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Application of Less Specific Screening Tools for Incident NPC in High-risk Multiplex Taiwanese Family Members (40+ years of age)

| IgA Marker | 5-year NPC Risk | Sensitivity | Specificity | # Screened per NPC Case | # Screen Positive per NPC Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCAp18 | 762 per 100,000 | 82% | 20% | 160 | 128 |

| VCAp18 + EBNA1 | 762 per 100,000 | 81% | 54% | 162 | 75 |

Utilizing the data from both the single VCAp18 IgA marker and single EBNA1 IgA marker rather than considering the combined VCAp18 + EBNA1 IgA peptide mixture did not offer superior discriminatory capacity. We created a composite score for each individual by multiplying the log odds for each IgA marker generated from a logistic regression model with the outcome of case status (VCAp18 IgA log odds: 0.0212; EBNA1 IgA log adds: 0.4714) by the VCAp18 IgA and EBNA1 IgA values for each individual. However, the delta statistic comparing the average value of this composite score between cases and non-cases was 1.04, identical to the EBNA1 IgA marker alone.

DISCUSSION

Our evaluation of a well-characterized, scalable panel of 5 anti-EBV IgA markers suggests that EBV serology measured prior to diagnosis can sensitively identify individuals from high-risk multiplex families with an elevated risk of developing NPC. In particular, the EBNA1 IgA marker applied in this population sensitively detected those diagnosed with incident NPC. In contrast, the two EA markers investigated (EAp138 IgA, Ead_p47 IgA) were present at very low levels prior to NPC diagnosis and were therefore not effective screening tools for incident disease. In a population at very high risk of developing NPC, such as the multiplex family members from Taiwan studied here, a screening program designed to detect disease and lower mortality needs highly sensitive screening tools (e.g. ≥80% sensitivity) that will target individuals at high disease risk for early detection and effective treatment, recognizing that increasing the sensitivity results in lower specificity. EBNA1 IgA, despite being a sensitive screening tool, was not highly specific when applied to this population. At an 80% sensitivity threshold value, approximately 40% of high-risk individuals who did not develop NPC also tested positive. While this test might be useful to reassure close to 60% of high-risk family members that they are not at an elevated risk of NPC within the next few years, screening efforts targeted towards the remaining 40% would benefit from marker combinations that increased test specificity, such as the incorporation of measures of nasopharyngeal EBV DNA levels. [21]

Importantly, application of this EBNA1 IgA marker resulted in 164 high-risk individuals needing to be screened, using a simple blood draw, for every incident case of NPC detected. This value is well within the range of number of high-risk patients that need to be screened for currently recommended screening programs in the US, such as low-dose computed tomography screening of high-risk patients for lung cancer to prevent 1 lung cancer death (N=302). [22]

These findings using a well-characterized panel of anti-EBV IgA markers are in agreement with the earlier data from Taiwan that utilized research-based EBV serology tests, suggesting that EBNA1 IgA is the most suitable marker in this high-risk population for identifying NPC. [14] Of note is that despite similar conclusions, the values for sensitivity and specificity for the respective EBNA1 IgA ELISA tests were not exactly the same, with the current peptide-based assay having slightly higher specificity. Our results that point to the utility of EBNA1 IgA antibody as a sensitive screening marker are further supported by large, ongoing NPC screening trials being conducted in China in areas with high endemic rates of NPC. [23–27] The sensitivity of the EBNA1 IgA assay utilized in that setting to diagnose NPC within a year of screening approached 90% and illustrated application of this screening tool in a general population setting for identifying those most likely to be harboring prevalent NPC. [28] However, it should be noted that the performance characteristics of any EBNA1 IgA test differ if applied to detect prevalent NPC that will present clinically within the following year versus incident NPC that will develop and present over the course of five years.

In addition to recognizing the importance of the specific screening tool employed, it is important to also define the prescribed clinical management of screen positive individuals, as a good screening test in the absence of a sensitive diagnostic work-up does not have high utility. For example, sending 69 high-risk individuals who tested above the given threshold for EBNA1 IgA for a routine, non-invasive clinical exam to detect 1 NPC case would not be as costly as sending those same 69 individuals for an invasive, expensive diagnostic procedure. Endoscopy, the current diagnostic procedure for NPC, is minimally invasive, so in a very high-risk population such as these multiplex family members, screening with a simple blood test that has modest specificity might be warranted, despite requiring a substantive number of individuals be sent for endoscopy. However, endoscopy may not be sensitive enough to detect very early stage NPC lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or another more expensive, potentially more invasive, test might be required. In this case the number of screen positives sent to receive this test for each real NPC case detected would become of greater concern.

Another important aspect to consider in the evaluation of potential screening tools is that selection of the target population alters the number of individuals needed to be screened per cancer case detected. Sensitivity of the EBNA1 IgA marker was lower when measured years prior to NPC diagnosis (e.g. incident NPC) in the high-risk multiplex family members as compared to measurement at the time of NPC diagnosis (e.g. prevalent NPC) in a general population setting. This result was not surprising; it is expected that EBNA1 IgA levels measured years prior to NPC diagnosis may be more variable and less accurate at diagnosing future, incident disease when compared to serology measurements taken from blood drawn at the time of NPC presentation. Available data suggests that elevated antibody titer may be informative for over a decade, although a more informative window may exist in the years immediately prior to NPC diagnosis. [12] This is supported by our data, which demonstrate that at the same cutoff value (EBNA1 IgA = 0.72), the sensitivity of the EBNA1 IgA marker among multiplex family members was marginally higher (sensitivity = 82%) when NPC cases diagnosed <5 years following blood draw were considered as compared to the entire set of NPC cases diagnosed over ~10 years (sensitivity = 80%).

The underlying incidence of cancer also has a large impact on screening parameters. In high-risk multiplex family members from Taiwan with an underlying NPC incidence on the order of 100 × 105, it was estimated that in an unscreened population, only 164 high-risk individuals would need to have blood drawn and screened at baseline for each case of NPC successfully detected over the following 5 years. In contrast, approximately 1,250 individuals would need to be screened per NPC patient detected if the same EBNA1 IgA marker were applied as a screening tool in the general, average-risk (NPC incidence = 10 × 105) Taiwanese population. [14] However, general population screening with EBNA1 IgA might be more feasible in high-risk areas such as the Guangdong province of China (NPC incidence = 50 × 105). [23] (Supplemental Table 1)

The interpretation of our results is limited by the modest sample size of this study; due to the fact that we are targeting a small but very high-risk subset of the population, only 21 incident NPC cases were detected. Replication in other existing high-risk or family-based NPC studies would be of interest. Furthermore, there is a circular nature to defining and subsequently applying our “optimal” threshold value in the same population. Again, this could be addressed through independent replication or application of this cutoff value in another high-risk NPC population.

Our evaluation of the application of EBNA1 IgA as a screening tool for incident NPC suggests that the number of individuals that would need to be screened per case detected in a high-risk population in Taiwan is comparable to currently recommended cancer screening programs in the United States. High-risk target populations are an ideal setting for further evaluation of the utility of EBV serology marker-based NPC screening. The currently available anti-EBV IgA antibodies tested here did prove to be sensitive tools for identifying individuals at elevated likelihood of developing future NPC, but further research is needed to identify more specific biomarkers that could triage EBNA1 IgA positive individuals and move towards more efficient NPC screening implementation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the intramural program at the National Cancer Institute

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of NPC. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:431–441. doi: 10.1016/s1044579x0200086x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raab-Traub N. Novel mechanisms of EBV-induced oncogenesis. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young LS, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:757–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de-The G, Lavoue MF, Muenz L. Differences in EBV antibody titres of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma originating from high, intermediate and low incidence areas. IARC Sci Publ. 1978:471–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henle G, Henle W. Epstein-Barr virus-specific IgA serum antibodies as an outstanding feature of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1976;17:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hildesheim A, Levine PH. Etiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:466–485. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanier A, Bender T, Talbot M, Wilmeth S, Tschopp C, Henle W, et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Alaskan Eskimos Indians, and Aleuts: a review of cases and study of Epstein-Barr virus, HLA, and environmental risk factors. Cancer. 1980;46:2100–2106. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801101)46:9<2100::aid-cncr2820460932>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgos JS. Involvement of the Epstein-Barr virus in the nasopharyngeal carcinoma pathogenesis. Med Oncol. 2005;22:113–121. doi: 10.1385/MO:22:2:113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo AK, Dawson CW, Jin DY, Lo KW. The pathological roles of BART miRNAs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2012;227:392–403. doi: 10.1002/path.4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niedobitek G, Agathanggelou A, Nicholls JM. Epstein-Barr virus infection and the pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: viral gene expression, tumour cell phenotype, and the role of the lymphoid stroma. Semin Cancer Biol. 1996;7:165–174. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1996.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien YC, Chen JY, Liu MY, Yang HI, Hsu MM, Chen CJ, et al. Serologic markers of Epstein-Barr virus infection and nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwanese men. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1877–1882. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji MF, Wang DK, Yu YL, Guo YQ, Liang JS, Cheng WM, et al. Sustained elevation of Epstein-Barr virus antibody levels preceding clinical onset of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:623–630. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao SM, Liu Z, Jia WH, Huang QH, Liu Q, Guo X, et al. Fluctuations of epstein-barr virus serological antibodies and risk for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective screening study with a 20-year follow-up. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu KJ, Hsu WL, Pfeiffer RM, Chiang CJ, Wang CP, Lou PJ, et al. Prognostic utility of anti-EBV antibody testing for defining NPC risk among individuals from high-risk NPC families. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1906–1914. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang C, Middeldorp J, Yu KJ, Juwana H, Hsu WL, Lou PJ, et al. Characterization of ELISA detection of broad-spectrum anti-Epstein-Barr virus antibodies associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Med Virol. 2013;85:524–529. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickard A, Chen CJ, Diehl SR, Liu MY, Cheng YJ, Hsu WL, et al. Epstein-Barr virus seroreactivity among unaffected individuals within high-risk nasopharyngeal carcinoma families in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:117–123. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu KJ, Hsu WL, Chiang CJ, Cheng YJ, Pfeiffer RM, Diehl SR, et al. Cancer patterns in nasopharyngeal carcinoma multiplex families in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1622–1625. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fachiroh J, Paramita DK, Hariwiyanto B, Harijadi A, Dahlia HL, Indrasari SR, et al. Single-assay combination of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) EBNA1- and viral capsid antigen-p18-derived synthetic peptides for measuring anti-EBV immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA antibody levels in sera from nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients: options for field screening. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1459–1467. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1459-1467.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hildesheim A, Anderson LM, Chen CJ, Cheng YJ, Brinton LA, Daly AK, et al. CYP2E1 genetic polymorphisms and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwan. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1207–1212. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.16.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wentzensen N, Wacholder S. From differences in means between cases and controls to risk stratification: a business plan for biomarker development. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:148–157. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens SJ, Verkuijlen SA, Hariwiyanto B, Harijadi, Paramita DK, Fachiroh J, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: nasopharyngeal brushings reveal high Epstein-Barr virus DNA load and carcinoma-specific viral BARF1 mRNA. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:608–614. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovalchik SA, Tammemagi M, Berg CD, Caporaso NE, Riley TL, Korch M, et al. Targeting of low-dose CT screening according to the risk of lung-cancer death. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:245–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Ji MF, Huang QH, Fang F, Liu Q, Jia WH, et al. Two Epstein-Barr virus-related serologic antibody tests in nasopharyngeal carcinoma screening: results from the initial phase of a cluster randomized controlled trial in Southern China. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:242–250. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng Y, Zhang LG, Li HY, Jan MG, Zhang Q, Wu YC, et al. Serological mass survey for early detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Wuzhou City, China. Int J Cancer. 1982;29:139–141. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910290204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng Y, Zhang LG, Wu YC, Huang YS, Huang NQ, Li JY, et al. Prospective studies on nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Epstein-Barr virus IgA/VCA antibody-positive persons in Wuzhou City, China. Int J Cancer. 1985;36:545–547. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910360505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng Y, Zhong JM, Li LY, Wang PZ, Tang H, Ma YR, et al. Follow-up studies on Epstein-Barr virus IgA/VCA antibody-positive persons in Zangwu County, China. Intervirology. 1983;20:190–194. doi: 10.1159/000149391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zong YS, Sham JS, Ng MH, Ou XT, Guo YQ, Zheng SA, et al. Immunoglobulin A against viral capsid antigen of Epstein-Barr virus and indirect mirror examination of the nasopharynx in the detection of asymptomatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 1992;69:3–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920101)69:1<3::aid-cncr2820690104>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Huang Q, Liu W, Liu Q, Jia W, Chang E, et al. Establishment of VCA and EBNA1 IgA-based combination by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as preferred screening method for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a two-stage design with a preliminary performance study and a mass screening in southern China. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:406–416. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.