Abstract

Purpose

Laser surgery has shown to exhibit several advantages over scalpel for many procedures. Some of these advantages include hemostasis, decreased scarring, and ability to perform certain procedures without anaesthesia. It has been postulated that laser surgery results in less post-operative pain. However this can be a difficult parameter to measure. This study sought to determine if there was a difference in the intensity and frequency of pain following excision with scalpel when compared to excision done with a CO2 laser.

Aims and Objective

(1) Hemostasis intra operatively and (2) pain, swelling and scarring post-operatively.

Materials and Methods

Thirty patients with bilateral (60 lesions) were selected for the entire proposed research. Group A: carbon dioxide laser excision (experimental group). Group B: scalpel excision (control group).

Result

(1) Intra operative bleeding is significantly higher in scalpel side compared to laser side treatment. (2) Percentage change (gained) in facial edema is significantly higher in scalpel side compared to laser side treatment. (3) Distribution of level of pain is approximately similar in both the treatments. (4) Distribution of scarring after 1 month post-operative pain is significantly higher in scalpel side compared to laser side treatment.

Conclusion

Through this study we can infer that CO2 laser supersedes conventional scalpel in terms of better intra-operative and reduced scarring. Post-operative pain and swelling after laser excision did not show any significant difference from that of scalpel.

Keywords: Lasers, Biopsies, Scalpel, Pain, Scarring, Bleeding

Introduction

Although there are various wavelengths used by oral and maxillofacial surgeons (CO2, Nd:YAG, erbium:YAG, holmium:YAG and copper vapour) the work horse has proved to be the CO2 laser. The CO2 laser has been recommended to treat benign oral lesions, such as fibromas, papillomas, hemangiomas, gingival hyperplasias with different causes (idiopathic or due to side effects of medications), aphthous ulcers, mucosal frenula or tongue ties (ankyloglossia), as well as premalignant lesions such as oral leukoplakias [1–3] Morphological and functional recovery following laser surgery is superior when compared with conventional instrumentation surgerys (scalpel) and electrocautery [4, 5] Compared to conventional surgery (scalpel), epithelial regeneration and wound re-epithelialisation are delayed [4, 5] but without any detrimental effect on outcome. Tuncer et al. [6] compared conventional surgery to laser surgery on oral soft tissue pathology. They evaluated the effect of collateral thermal damage on histopathological diagnosis, pain control and post-operative complications. Histological examination of the specimens showed that collateral thermal damage on the incision line did not have adverse effect on the histopathological diagnosis. Laser devices emit energy via chromatic radiation in either the visible, infrared or ultraviolet region of the spectrum. They produce in-phase waves and transmission of heat and power when focussed at close range. In oral surgery; lasers are often used to perform oral biopsies. Biopsy is a surgical procedure performed to establish a clear diagnosis of a lesion, and to confirm a suspected clinical diagnosis.

The biopsy may be incisional or excisional. The former process removes one or more tissue samples to establish an effective therapy based on a histological diagnosis; the latter is the complete removal of the lesion, so it is a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure [7].

Materials and Methods

Thirty patients with bilateral lesions (60 lesions right and left buccal mucosa) who required excision for biopsy involving the oral cavity were selected for the entire proposed research. Group A: carbon dioxide laser excision (experimental group) Group B: scalpel excision (control group) Carbon dioxide laser unit-Union medical model no: UM-L25, 2012 with an input voltage of 220 V/50 Hz and power consumption of 500 W classified as class I, b type (size 940 × 400 × 400 mm). Along with it is a union medical evacuator surgical set of instruments: this would include diagnostics instruments, scalpel and BP blade no 15, punch biopsy instruments, retractors, Addisons and Allis forceps. Local anesthesia 2 % xylocaine with adrenaline 1:200,000. Biopsy containers with 10 % formalin solution.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients of both sexes, aged between 15–70 years, who presented with bilateral oral leukoplakia of similar clinical presentation and at similar site measuring <2 cm, occurring in the buccal mucosa any where from the corner of the mouth anteriorly to the pterygomandibular raphe region posteriorly.

Exclusion Criteria

HIV and other immunosuppressive disorder, pregnancy, lactation, allergy to lignocaine, patients on contraceptives/steroids and patients unfit for surgery. Other exclusion criteria specific to the study were patients with multifocal leukoplakia, lesions measuring more than 2 cm.

Procedure

Detailed history, clinical examination and necessary investigations were performed in standard manner, for any patient undergoing surgical excision of leukoplakia as according to the department protocol.

Written informed consent was taken after explaining the procedure.

All patients were operated under local anesthesia using infiltration with xylocaine 2 % containing 1:200,000 epinephrine (1.5 ml each side). Standard surgical procedure of excision of the lesion was performed. One side of the lesion will be excised using CO2 laser (experimental group A) and the other by scalpel surgery (control group B). Side selection was a randomized process. Scalpel excision was conducted using a 15 no surgical blade.

Continuous wave CO2 lasers having a high power continuous output and having a infrared wavelength of 10.6 microns was used for the purpose of this research. Focal spot and the penetration depth was adjusted by changing the power density of the machine. We would use a focal spot (approximately 1.5 mm) for excision of the lesion, with voltage in the range of 5–8 W in focused mode.

Haemostasis was achieved with a pressure pack (gauze pieces) suturing was done and post-operative antibiotic and analgesic prescribed.

Pain will evaluated on VAS scale

| Score | VAS scale to evaluate pain | Patient score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No pain | Patient feels well | |

| 1 | Slight pain | Patient is distracted. He or she does not feel pain | |

| 2 | Mild pain | Patient feels pain even if concentrating on some activity | |

| 3 | Severe pain | Patient is very disturbed but can continue with normal activities | |

| 4 | Very severe pain | Patient is forced to abandon normal activity | |

| 5 | Extreme severe pain | Patient must abandon every activity and feel the need lie down |

Facial swelling assessment

|

Vancouver scar assessment scale

| Contour | Distortion | Texture | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flush with surrounding skin | None | Normal |

| 2 | Slightly proud | Mild | Just palpable |

| 3 | Hypertrophic | Moderate | Firm |

| 4 | Keloid | Severe | Hard |

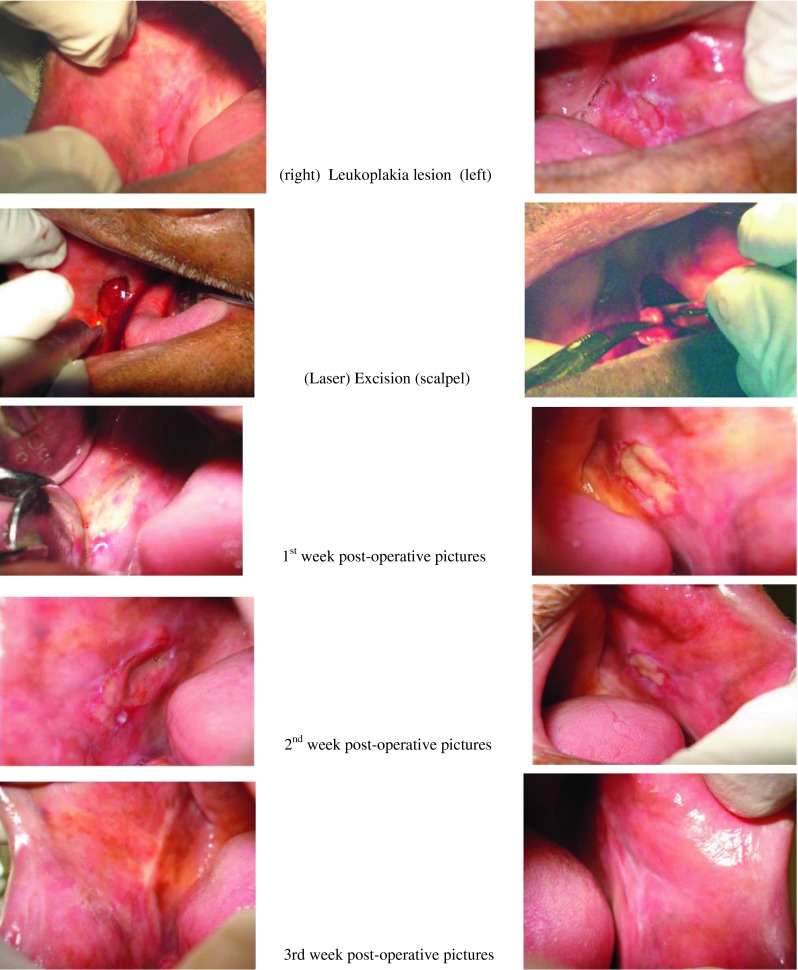

Case 1 pictures

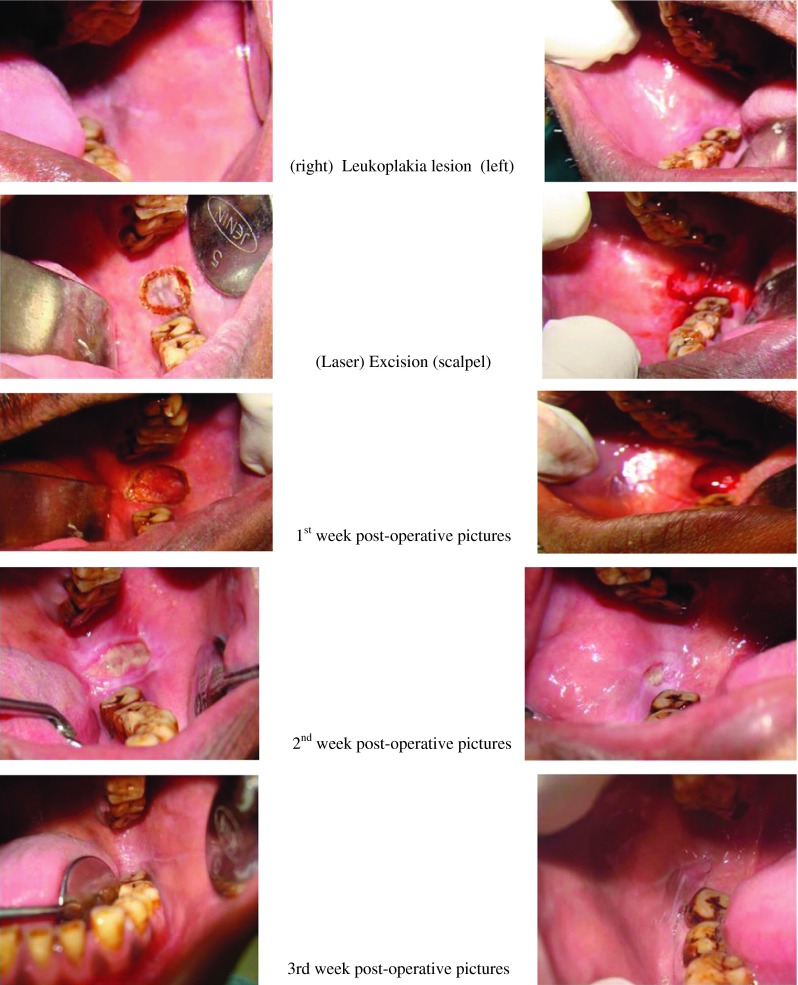

Case 2 pictures

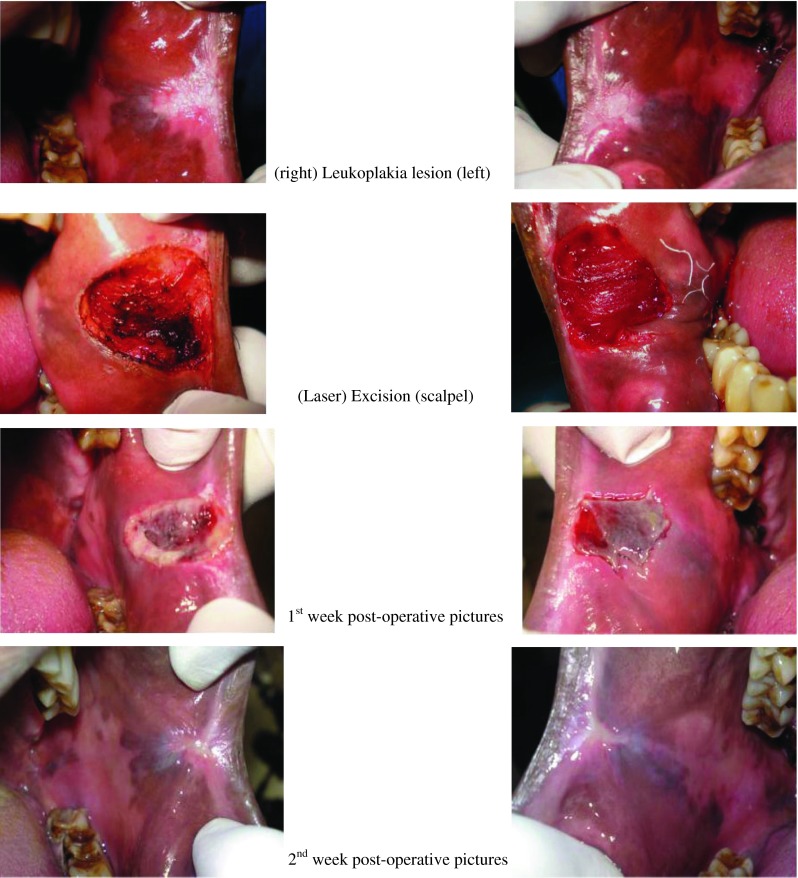

Case 3 pictures

Results

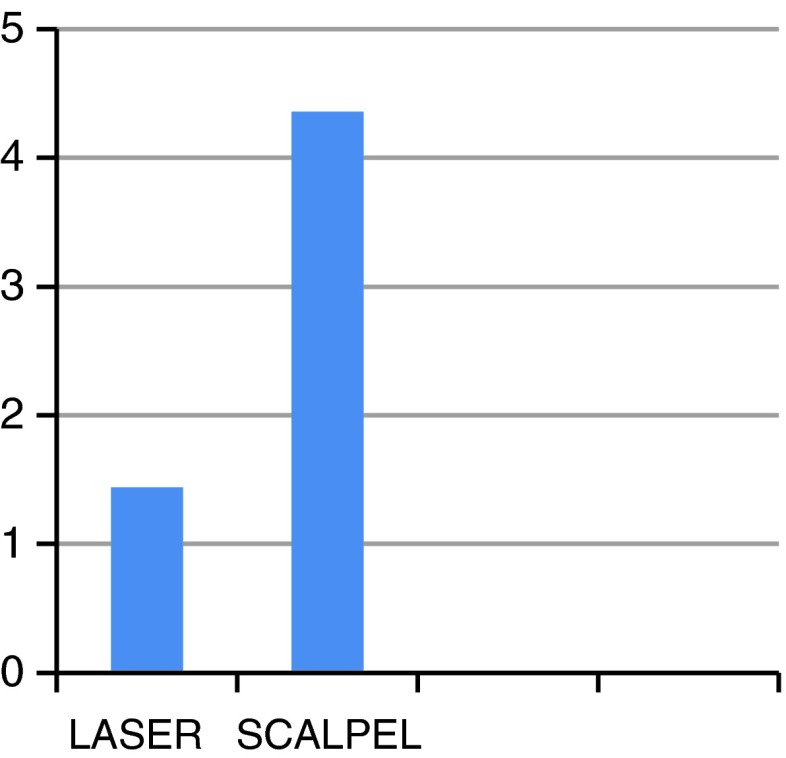

Distribution of bleeding index between two treatments

Comment: operative bleeding is significantly higher in scalpel side compared to laser side treatment (bleeding at every operative site was calculated using the number of gauze pieces with the difference in their dry and wet weight).

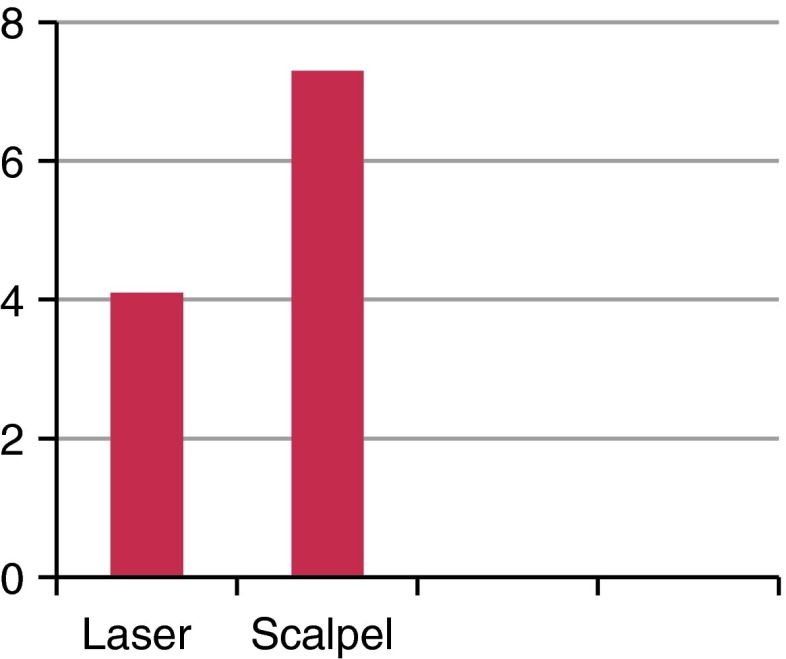

Distribution of change in facial edema between two treatments

Comment: percentage change (gained) in facial edema is significantly higher in scalpel side compared to laser side treatment (change in facial oedema is calculated according to the above given facial edema assessment algorithm).

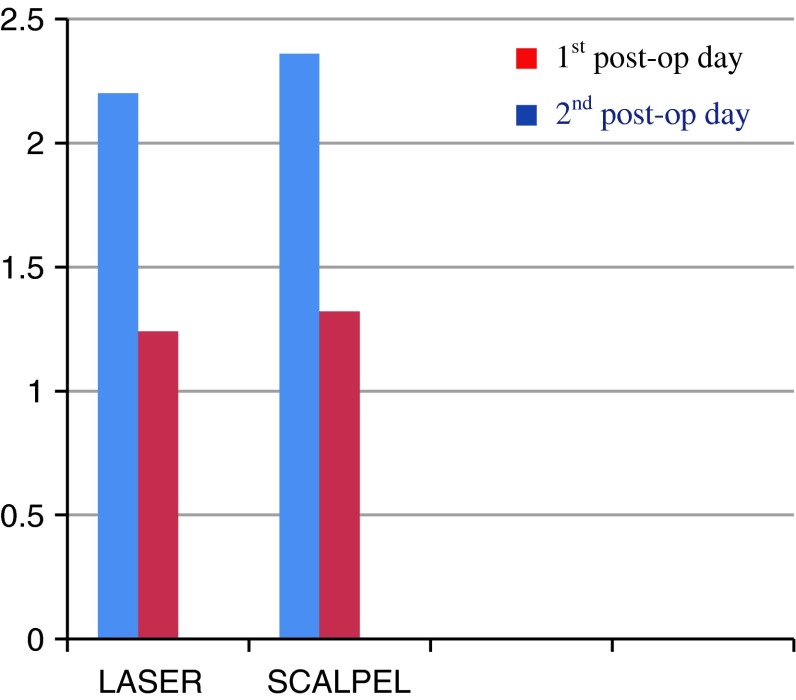

Distribution of pain between two treatments

Comment: distribution of level of pain (at both the follow-ups that is 1st day post-op and 2nd day post-op) is approximately similar in both the treatments (Y axis is the mean value).

Distribution of pain between two treatments

| Parameter [pain (VAS)] | Laser site (n = 25) | Scalpel site (n = 25) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st post-op day (mean SD) | 2.20 (0.41) | 2.36 (0.49) | 0.212 |

| 1st post-op day (categories) | |||

| No pain | 0 | 0 | 0.208 |

| Slight pain | 0 | 0 | |

| Mild pain | 20 (80.0) | 16 (64.0) | |

| Moderate pain | 5 (20.0) | 9 (36.0) | |

| Severe pain | 0 | 0 | |

| Intense pain | 0 | 0 | |

| 2nd post-op day (mean SD) | 1.24 (0.44) | 1.32 (0.48) | 0.533 |

| 2nd post-op day (categories) | |||

| No pain | 0 | 0 | 0.529 |

| Slight pain | 19 (76.0) | 17 (68.0) | |

| Mild pain | 6 (24.0) | 8 (32.0) | |

| Moderate pain | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe pain | 0 | 0 | |

| Intense pain | 0 | 0 | |

Values are mean (SD). P value by Mann–Whitney U test, a non-parametric test to test the significance of difference between two independent groups

Values are n (%). P value by Fischer’s exact test

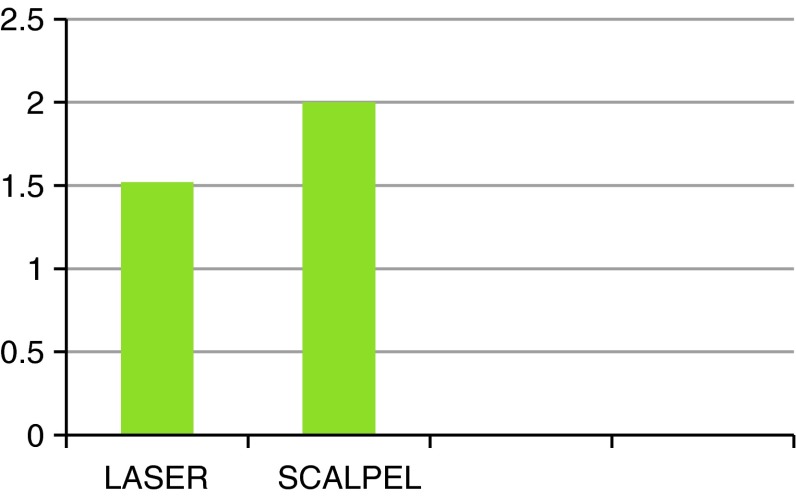

Distribution of scarring between treatments

Comments: distribution of scarring after 1 month post-op is significantly higher in scalpel side compared to laser side treatment (Y axis is the mean value).

| Parameter | Laser site (n = 25) | Scalpel site (n = 25) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scarring after 1 month (after 1 month) (mean SD) | 1.52 (0.68) | 1.95 (0.69) | 0.045 |

| Scarring (after 1 month) levels | |||

| No scar | 0 | 0 | 0.038 |

| Excellent/mild scar | 12 (57.1) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Good/moderate scar | 7 (33.3) | 11 (55.0) | |

| Fair/severe scar | 2 (9.5) | 4 (20.0) | |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | |

Values are mean (SD). P value by Mann–Whitney U test, a non-parametric test to test the significance of difference between two independent groups

Values are n (%). P value by Fischer’s exact test

Discussion

Leukoplakia is considered to be a common oral premalignant lesion [8, 9]. There are numerous treatment regimes for oral leukoplakia including surgical managements like excision, cryotherapy laser therapies, as well as medical managements like retinoids and vitamin A.

Literature in the past suggests the recurrence of oral leukoplakia to be in the range of 7.7–38.1 %, while for the malignant transformation 1.2–17.5 % [10, 11] .The recurrence rate for local excision varies from 10–34 %, and recurrence rate for cryosurgery varies from 13–25 %.

Surgical treatment of oral leukoplakia (lesion confined to epithelium or sub mucosa) using CO2 laser can be best obtained by ablation or vaporization of the lesion. Ablation being done at defocused mode (achieved by moving the laser away from the tissue and beyond its focal length), reduces the power and depth of penetration of the laser beam [12] (200–400 μm per pass), limiting the destruction to the epithelium and hence resulting in lesser pain, swelling and even scarring with better regain of elastic property of the tissue [13]. However ablation of the lesion precludes histopathological study.

In our study we use the technique of excising the tissue to facilitate histopathological study of the biopsy specimen for both the sides to confirm the presence of dysplasia and compare its severity. The excision with CO2 laser is operated in focus mode and it occurs when the spot size is maintained at the focal point of the laser. In focused mode, the power per unit area is maximized and the depth of cut is increased, resulting in a deep, thin cut as would be seen with a scalpel. Greatest significance is the high degree of absorption by oral mucosa tissues, which are composed of 90 % water. Absorption of the laser by intracellular water results in a photo thermal effect that is manifested by cellular rupture. This cellular vaporization is the basis for the use of CO2 as a surgical tool. Lateral thermal damage results in coagulation of vessels up to 500 mm in diameter and is clinically manifested by hemostasis. Post-surgical bacteremia also has been found to be greatly reduced with laser use as a result of sealing of blood vessels and lymphatics compared with other methods of incision [14]. Given a potential 500 mm zone of lateral necrosis, all the margins were planned 1 mm beyond the normal margins to prevent thermal effect encroached upon the actual lesion.

Our study population consisted of 30 patients presenting with similar bilateral leukoplakic lesions that is 60 lesions. Scalpel was used to excise the tissue on one side and CO2 laser was used to excise the tissue on the opposite side, both the sides were operated on the same day, selection of sides was done in a random manner. In our study males dominated females, population ranged between 22 and 70 years of age 68 % were cigarette smokers over more than 5 years duration and 88 % were tobacco chewers. CO2 laser was more time consuming ranging from 6–10 min when compared to scalpel which ranged from 3–6 min. It was found that laser excised lesions had considerably lesser blood loss than lesion excised with scalpel therapy facilitating good intra-operative hemostasis.

Suturing was necessary in 60 % of our cases treated with scalpel compared to 15 % in laser treated cases owing to the better hemostatic property of laser, undermining was done for the 15 % of laser treated cases.

Lack of pain, is one the most curious, yet unexplained findings with the laser. In our series of cases the finding of post-operative pain on the 1st and 2nd day was similar in both the laser and the scalpel site.

Sealing of lymphatics and blood vessels by the laser fluids helped to explain minimal inflammatory response around the wound. By contrast, scalpel wound allows extravasation of blood and lymphatics, resulting in more swelling and inflammatory response, which takes longer to resolve.

The percentage change in facial edema being considerably less in the laser side compared to that of scalpel.

Laser wound exhibit histological features that confer significant advantages over those created by scalpel or electro surgery. Most significantly, laser wounds have been found to contain significantly lower number of myofibroblasts [15], resulting in minimal degree of wound contraction and scarring.

Compared with scalpel wounds, which generally heal in 7–10 days, laser wounds may take 2–3 weeks to heal completely [12]. It is not uncommon for patients to exhibit an increase in pain 4–7 days post-operatively which usually is easily managed with oral analgesics.

In our series of patients scarring was accessed in 20 patients who followed-up for a period of 1 month. We found that healing was much better with laser excision with the resultant reduced scarring compared to scalpel.

There are significant disadvantages; of primary consideration are the radiant energy hazards to the patients, surgeon, and operative team from inadvertent exposure resulting in laser skin burns, eye damage and blindness. Other disadvantages include the great expense of the laser equipment and service fees, the need for additional training of the surgeon and operating team and continuous maintenance and upgrading of the evolving technology. While considering the treatment of oral soft tissue lesion, one needs to consider other factors such patients cost, health hazards.

Conclusion

Because of its comfort level for the operator and the patients benefit, CO2 laser can be recommended in oral therapy. It is a precise means of removing soft tissue lesions in selected patients. Patient post-operative satisfaction after laser excision was greater when compared with those who had conventional excisions. Postoperative pain was less, as was the pain experienced during the first week of recovery. Through our finding we can infer that CO2 laser supersedes conventional scalpel in terms of better intra-operative hemostasis and reduced scarring.

References

- 1.Strauss RA. Lasers in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;44:851–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornstein MM, Suter VGA, Stauffer E, Buser D. The CO2 laser in stomatology: part 2. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2003;113:766–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suter VGA, Bornstein MM. Ankyloglossia: facts and myths in diagnosis and treatment. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1204–1219. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roodenburg JL, Witjes MJ, de Veld DC, Tan IB, Nauta JM. Lasers in dentistry 8. Use of lasers in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2002;109:470–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burkey BB, Garrett G. Use of the laser in the oral cavity. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1996;29:949–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuncer I, Ozçakir-Tomruk C, Sencift K, Cöloğlu S. Comparison of conventional surgery and CO2 laser on intraoral soft tissue pathologies and evaluation of the collateral thermal damage. Photomed Laser Surg. 2002;31:145–153. doi: 10.1089/pho.2008.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romeo U, Palaia G, Ripari F, Tenore G, Del Vecchio A. The use of laser in oral biopsies. World Dent Online

- 8.Pindborg JJ (1980) Oral cancer and precancer. Bristol: Wright 15

- 9.Silverman S, Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation: a follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53:563–568. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<563::AID-CNCR2820530332>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hogewind WF, van der Kwast WA, van der Waak I. Oral leukoplakia with emphasis on malignant transformation: a follow-up study of 46 patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17:128–133. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(89)80085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverman S, Bhargarva K, Mani NJ, Smith LW, et al. Malignant transformation and natural history of oral leukoplakia in 57, 518 industrial workers of Gujarat, India. Cancer. 1976;38:1790–1795. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197610)38:4<1790::AID-CNCR2820380456>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss RA. Lasers in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Dent Clin N Am. 2000;44:851–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roodenburg JL, Ten Bosch JJ. Measurement of the uniaxial elasticity of oral mucosa in vivo after CO2 laser evaporation and surgical excision. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;19:181–183. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaminer R, Liebow C, Margarone JE, Zambon JJ. Bacteremia following laser and conventional surgery in hamsters. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:45–48. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeinoun T, Nammour S, Dourov N, Aftimos G, Luomanen M. Myofibroblast in healing laser excision wounds. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:74–79. doi: 10.1002/1096-9101(2001)28:1<74::AID-LSM1019>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]