Abstract

Aim

To compare the displacement gap of mandible fracture segments treated with different designs of mini-plates under various loading conditions.

Materials and Methods

Fracture in the body of mandible was bridged with 15 different designs and configuration of titanium mini-plates. Bite forces were applied at 3 locations, ipsilateral fractured side, contra lateral side and incisor site. 3D finite element methods (FEM) model of mandible was generated using 10 nodal tetrahedral elements. A commercial FE solver was used to solve bone inter fragmentary displacement during loading.

Results

Superior position of mini-plates produced better stability than inferior position. Positive bending moments can be reduced by larger plate in lower border in 2 plate system. Results of X mini-plate are comparable to 2 plate configuration. If length of middle portion of plate increased, stability decreased. Number of screws did not affect fracture stability.

Conclusion

Finite element methods analysis is used to determine the gap between mandible fragments which is otherwise impossible to measure clinically. The results obtained from this study offered us a choice of mini-plate design and configuration for clinical application.

Keywords: Rigid fixation, Body of mandible fracture, Titanium mini-plates, Finite element method analysis, Osseointegration

Introduction

The mandible is the second most commonly fractured part of the maxillofacial skeleton because of its position and prominence [1, 2]. Fractures of the angle and body of the mandible are referred to as favorable and unfavorable depending on the angulations of fracture and force of the muscle pull proximal and distance to fracture. The unfavorable fracture of the angle of mandible results in displacement of fragments.

Open reduction and internal fixation being the mainstay of the treatment line for such displaced fractures, the literature reveals utilization of varied designs and shapes of the mini-plates. Mini-plates are used as the devices for fixation and stabilization of fragments. Different designs and shapes of the mini-plates have their own advantages and disadvantages.

In order to decide the most suitable design for treatment of such fractures the FEM (finite element methods) analysis plays a major role. FEM is a numerical method allowing modeling of structures that approximate reality.

Materials and Methods

The present study is performed to analyze the behavior of fractured mandibles after fixation with mini-plates having different numbers, locations, and design types. For this purpose, a 3D FEM model of the mandible was developed. High bending moments at the body caused by bite forces on the incisors pose a challenging problem for any fixation appliance [3]. Therefore, a complete fracture on the right body of the mandible was selected for this investigation. The type and positioning of the mini-plates were determined in accordance with the clinical application.

3D Mandible Model Creation

The FE software required vectorial definition of the geometry [4]. A nondestructive procedure to quantify morphometric data of the body was used based on the use of computerized tomography (CT) scans. This method proved advantageous for the construction of realistic and accurate 3D computer models [5]. The constructed model was equivalent of the real object in several aspects [6]. Multi-slice Spiral CT scanner which is made by Philips in Netherlands was used to scan the patient. The scanning condition is 120 kV, 400 mA, 1,500 mS, the horizontal distinguish is 1,024 × 1,024. The scan planes are parallel lines of Frankfort Horizontal Plane. The scan thickness is 1.5 mm [7]. 2-D pictures were procured, and put out with Dicom files. These Dicom files were delivered to the Slicer Version4 software. Then threshold 405 of CT gray value was selected to reverse the model of mandible. The grey scale above 1676 was extracted using the grey valve scale selection. The additional noise was eliminated with the method that is the same to extract the mandible. The high quality 3D model of the mandible and lower denture was obtained. The integrity of the model was verified and exported in STL (Standard Tessellation Language) format. The STL data model was optimized in Geomagic to get a close match with the mandible model to be analyzed. XYZ coordinate system was assigned to the model such that the origin is located on the X–Y plane at a point midway between the left and right condylar processes and the X direction is mediolateral, the Y direction is superoinferior, and the Z direction is anteroposterior. Teeth do not add to the mechanical strength/stiffness of the mandible. In present FE modeling, the limited role of the teeth in mechanical response of the mandible is ignored and removed to simplify the modeling [4]. In most of the literature, the properties of bone were assumed to be same in every plane and not exhibit any nonlinear stress strain characteristics i.e., the bone is isotropic, homogeneous, and linearly elastic [5]. The behavior is characterized by the two material constants viz., Young modulus and Poisson ratio. The Young modulus was taken as 14,000 MPa, and Poisson ratio was 0.3.

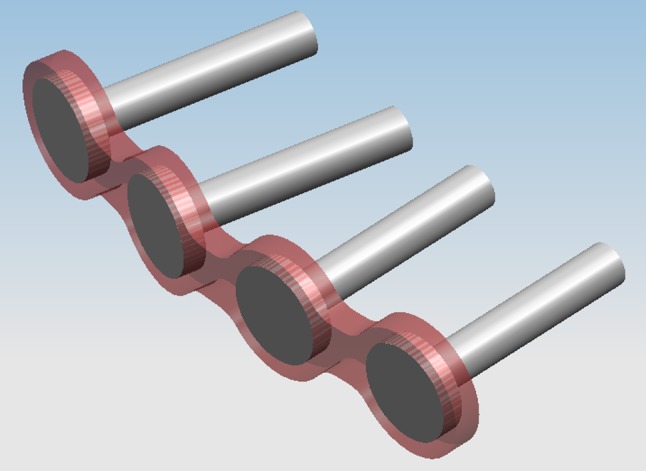

Generation of Plate and Screws Models

Two millimeter thick titanium mini-plates of different designs were modeled. Real mini-plates were scanned and the image files imported to AutoCAD and were used to sketch mini-plates in two dimensions using a combination of lines and curves. This 2D geometrical CAD data was imported to Unigraphics CAD (Computer Aided Design) software package where it was converted to 3D data. Also adaptation between mini-plate and screws were done using Unigraphics CAD software. Material properties were assigned for titanium as 1.1 E5 MPa for Young modulus and 0.34 for Poisson ratio (strain limit −0.2 %). The monocortical titanium screws of 8 mm length were also modeled as simple cylinders for appropriate penetration, and the same material properties of titanium were used (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Screw and plate model

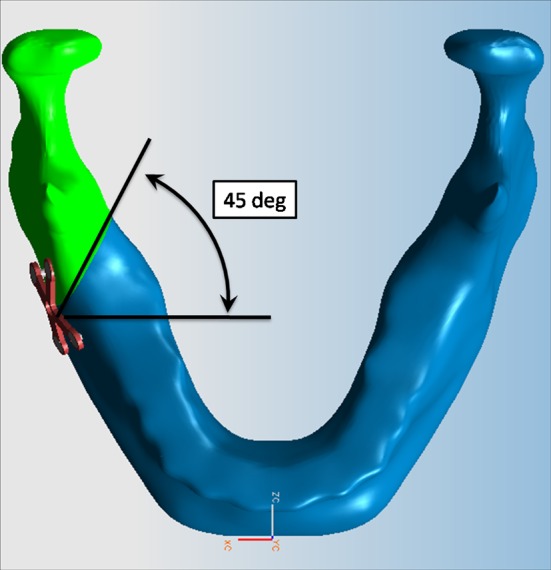

Fracture Site Creation and Bridging with Mini-Plates

High bending moments at the body caused by bite forces on the incisors pose a challenging problem for any fixation appliance [3]. Therefore, a complete fracture on the right side body of the mandible was selected for this investigation. Fracture was created distal to the second molar on the right side of the mandible at a 45 degree angulation using Unigraphics CAD software package. The left side was considered the non-fractured side. A fracture with inter-fragmentary bone contact was simulated. The fracture line was slightly rough and without deep serrations. The two bone fragments were fixed together. To take into account the contact phenomena between two fragments of the fractured mandible, appropriate contact conditions were defined (Fig. 2).

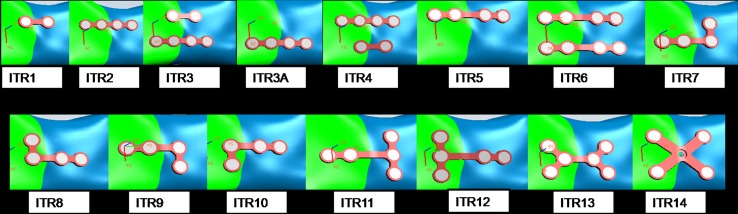

Fig. 2.

Different mini-plate configurations studied

Thus the computer automatically calculated even if the two fractured halves were touching each other or not. In displaced shape of the loaded mandible, if one part reaches the other, penetration is prevented [4]. Mini-plate should be perfectly adapted to the underlying bone to prevent alterations in the alignment of the segments and changes in the occlusal relationship. Proper adaptation of titanium mini-plates is generated using Unigraphics CAD software. The plates were fixed to the bone with screws. Perfect adaptation between plate holes and screws through which it was mounted as well as the screw and hosting bone with no slippage at their interfaces was assumed [8]. The bone fragments were assumed to be in perfect contact with each other after repositioning and plate fixation.

In ITR1 design, two hole straight mini-plate (type I1) was placed on the superior border (about 9–10 mm from the superior border to reduce the risk of root perforation) of fracture section. In ITR2 design, I2 mini-plate is used in the upper border. In ITR3 design, I1 and I2 mini-plates were used in upper and lower border of the fracture segments respectively. In ITR3A design, I2 mini-plate was fixed in the inferior border of fracture site. In ITR4, both I2 and I1 plates were used. I2 plate was placed on superior border and I1 plate was placed on inferior border. In ITR5 design, I3 mini-plate (four holes with gap) was used in the upper border of fracture. In ITR6 design, two I3 mini-plates were used across fracture site at both upper and lower borders.

ITR7, ITR8, ITR9, ITR10 designs represented different orientations of L mini-plates (L1, L2, L3, L4 respectively). L mini-plates were placed across middle of the fracture section symmetrically.

ITR11 and ITR12 designs showed different orientation of T mini-plates (T1, T2). Two types of X mini-plates are represented in designs ITR13 and ITR14. In ITR13, fractured segment is bridged with diagonal X-shaped mini-plates with six screws (X1) at the middle of fracture section. Four holed X mini-plate (X2) was used in the middle of mandible fracture site in ITR14 (Table 1, 2).

Table 1.

Different mini-plate designs studied

| Mini-plate design | No. of screws | Graphic representation |

|---|---|---|

| I1 | 2 |

|

| I2 | 4 |

|

| I3 | 4 (with gap) |

|

| T1 | 5 |

|

| T2 | 5 |

|

| L1 | 4 |

|

| L2 | 4 |

|

| L3 | 4 |

|

| L4 | 4 |

|

| X1 | 4 |

|

| X2 | 6 |

|

Table 2.

| Male | Female | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 293 | 208 | 242 |

| 2 weeks | 60 | 69 | 66 |

| 4 weeks | 127 | 129 | 128 |

| 8 weeks | 184 | 199 | 193 |

| 3 months | 245 | 251 | 249 |

| 6 months | 251 | 276 | 301 |

Boundary Conditions and Muscle Force

Validity of analysis result depends on mimicry of model, boundary conditions, loading condition, and material modeling in accordance with the physical reality [9]. During the application of bite forces or loadings, to prevent rigid body rotation and translation, a substantial simplification of the boundary conditions is assumed and the transitional degree of freedom of the condyles is set to zero [4]. Such a fixation is necessary to avoid singularities in global stiffness matrix to have a solution [10]. On the other hand, during biting or daily function of the jaw the movement of the mandible is prevented where the muscles and ligaments attach to the mandible as well as the condyles [4]. Closing muscle force vectors (path of origin to insertion) were assigned based on published work by Van Eijden et al. [7]. The magnitude of the force in each muscle was assumed to be directly proportional to the muscle cross-section as reported in the same study. The sum of all of the muscle forces was calculated to create a moment sufficient to balance the prescribed bite force about a pivot point at the condyle. The condyle was fixed in all three spatial directions to represent the reaction force at the temporomandibular joint [11].

Loading Condition-Biteforce

Fractures located in the angle, body, and symphysis regions each has a characteristic pattern of loads across the fracture. Besides, for each fracture site, the loads across the fracture have different values for bite forces applied on the molars, premolars, canines, or incisors [12–14]. So in this model, bite forces are applied at three different locations, ipsilateral fractured site (right molar region), contralateral non fractured site (left molar region) and incisor site. (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fracture line

The bite forces are the loading on the mandible during its daily functioning. Maximum bite force has been demonstrated to be between 300 and 400 N for the average non-injured man and less in a woman. Bite forces are reduced during the fracture healing period in patients with mandibular fractures.

Maximum bite force values are different in the molar, premolar, canine, and incisor regions, with highest bite forces in the molar region and lowest forces in the incisor region. Tate et al. [15] established bite forces in both normal patients and those who had been treated for mandibular fractures. They grouped measurements into those taken before 6 weeks post-surgery and those taken at more than 6 weeks post-surgery. Before 6 weeks the average incisor bite force was 62.8 N and molar bite force was 119 N. These forces were used in the current FEA study.

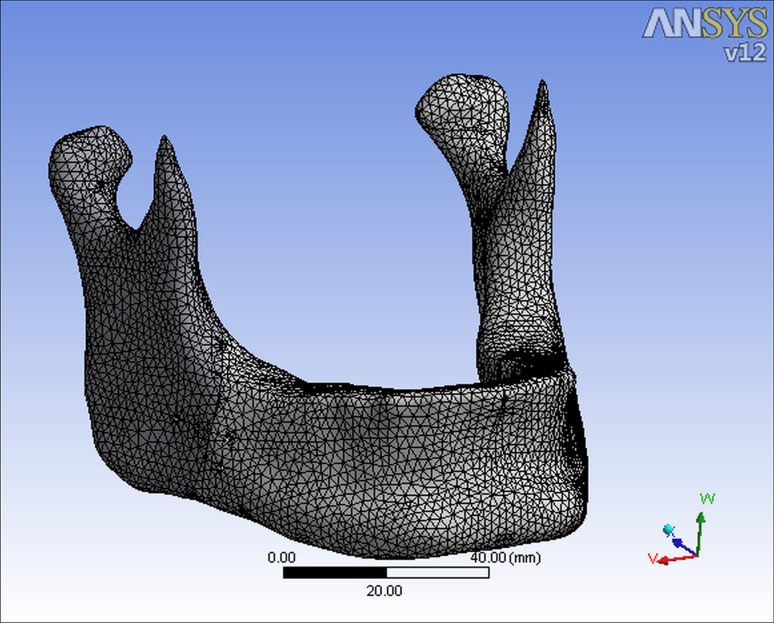

FEM Model Generation

Solid model of the fractured mandible, adapted mini-plates and screws are imported into ANSYS Workbench FEM software. ANSYS workbench has interactive three-dimensional finite element model generation GUI for modeling a multi-connected mandible structure. FEM model is broken down into approximately one lakh finite elements which are connected by nodes. The 10 nodes tetrahedron is chosen as the basic element type due to its rigorous adaptability to structures with geometric complexities. The material properties were assigned to the FEM model (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

FEM mesh

Interaction of the pieces is considered by an FE contact analysis using ANSYS software. The contact problem is of a nonlinear type, in which the system stiffness matrix is modified so that the contribution of the separate pieces is taken into account according to the state of contact. ANSYS has 3 different types of contact analyses: node-to-node contact, node-to-surface contact, and surface-to-surface contact [4]. In a contact analysis, the regions of possible contact during the deformation of the model need to be identified. Later, contact regions are defined via target and contact elements, which will then track the kinematics of the deformation process. Contact elements were constrained against penetration into the target surface at their integration points [16].

When factors such as boundary conditions and loading stress are applied to the model, the deformations and stresses of these simple elements can be calculated at each node. Due to their mutual interlinking, displacement and deformation of overall structure can be calculated using FEM software.

Thus FEM software calculates the stress across the mini-plate, bending and torsion moments in fracture site resulting from the bite force and the muscle and joint reaction forces that act on the proximal and distal fragments. Fracture mobility, i.e. movement of the proximal fragment with respect to the distal one and the displacement gap between fracture segments while loading all the three bite points are calculated across the three axes (mediolateral direction), Y (superioinferior), Z (anteroposterior) direction. Thus this 3D model was successfully used to evaluate the stability between mandible fragments treated with different designs of mini-plates under various loading conditions, which proved the viability and effectiveness of the proposed method.

Results

The gap distance or separation of the fracture section indicates stability or rigidity of the fixed bone fragments of the mandible [4]. Stability is required for appropriate osteogenesis and bone healing [3]. The vectorial summation of 3D translational displacements of the nodes on the fracture section gives the separation or gap distance, i.e., the movements in the X, Y, and Z directions (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Gap in various mini-plate configurations

All Clinical observations showed that the upper limit of relative movement of the segments of mandible fracture under the bite forces should not exceed 150 μm (0.15 mm), i.e. the limit of mobility.

It was found that all bite points on the fractured side resulted in negative bending moments. Here, zone of tension appeared on lower border. The bite points on the non-fractured side resulted in positive bending moments only. In this case gap appeared on upper border and zone of compression appeared on lower border. In the body fracture, maximum bending and torsion moments were in the same range. So in body fracture torsion effect cannot be neglected.

By comparing ITR2 and ITR3A, superior position of mini-plate produced better stability than inferior position. According to Dichard and Klotch two-plate systems provide the greatest ability to neutralize forces applied across the fracture line whether 2D or 3D loading occurs [17].

As the length of the middle portion increased, stability decreased. So ITR2 is better than ITR5.The reason for this is that the displacements are increased in a beam supported at both ends as the span length of the beam gets larger [4].

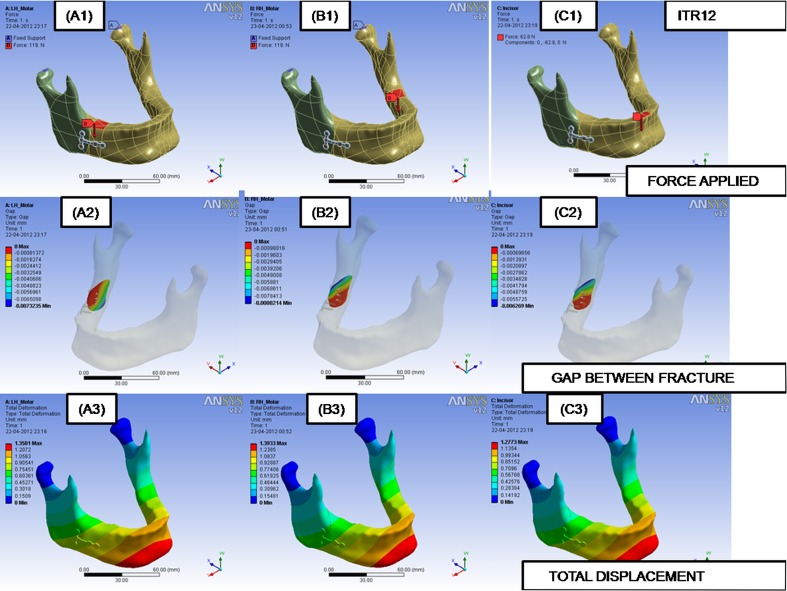

L mini-plates produced similar values. This reveals that the orientation of the mini-plate is not an important parameter. L plates are placed in the middle of the fracture segments. So it is not as good as straight mini-plate to withstand bending moments (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

FEM model setup and results of ITR12 (T2 Plate). A1 bite load application on molar left hand side. B1 bite load application on molar right hand side. C1 bite load application on incisor side. A2, B2 and C2 their respective gap displacements. A3, B3 and C3 their respective total displacements

It has been observed in the study that T2 (ITR12) plate gives better stability in displaced body or angle fracture. Gap between fragments are reduced when there is 3 screws on left side of fracture. As the body fracture is at an angle of 45 degree to mandibular plane, 3 screws on the left side passed through both the right and left fragments.

X mini-plates gave satisfactory results. X plate is better than L and T plate. Since the fracture is at an angle of 45 degree to mandibular plane, X plate, on the left side of fracture fragment passes through both fragments and adds to the rigidity of fracture fragments.

Again, the number of screws did not affect the stability considerably. ITR14 design, i.e. X mini-plate with 4 holes gave sufficient bracing effect across fracture segments and the displacement gap values are comparable with ITR3 design. The worst behavior was seen in single mini-plates placed inferiorly (ITR3A).

Discussion

The first and most important aspect of surgical correction is to reduce the fracture properly and place the individual segments of fracture into proper relationship with each other.

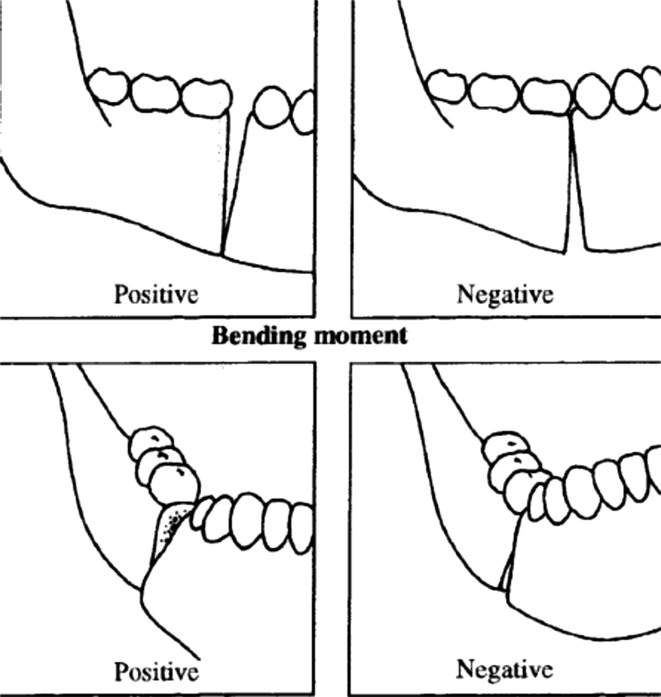

Basic principles of mandibular fracture treatment include reduction, fixation, immobilization, and supportive therapies. It is well known that union of the fracture segments will only occur in the absence of excessive mobility. Stability of the fracture segments is a key factor for proper hard and soft tissue healing in the injured area. Therefore, the fracture site must be stabilized by mechanical means in order to help the physiologic process toward normal bony healing (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The direction of the bending and torsion moments [14]

Fixation must be able to resist the displacing forces acting on the mandible. It can take one of two forms: direct or indirect. When direct fixation is used, the fracture site is opened, visualized, and reduced; then stabilization is applied across the fracture site. The rigidity of direct fixation can range from a simple osteosynthesis wire across the fracture (i.e. non-rigid fixation) to a mini-plate at the area of fracture tension (i.e. semi-rigid fixation) or a compression bone plate (i.e. rigid fixation) to compression screws alone (lag screw technique).

Indirect fixation is the stabilization of the proximal and distal fragments of the bone at a site distant from the fracture line. The origin of plating as a treatment option for fractures can be traced to Dannis and colleagues, who reported the successful use of plates and screws for fracture repair in 1947 [18]. Later refinement of this technique is credited to Allgower and colleagues at the University of Basel, who successfully used the first compression plate for extremity fracture repair in 1969 [19]. However, it was not until 1973 that Michelet and colleagues reported the use of this treatment modality for fractures of the facial skeleton [20]. In 1976 following Michelet’s success, a group of French surgeons headed by Champy developed the protocol that is now used for the modern treatment of mandibular fractures.

Basically, there are two categories of plating systems: rigid compression plates such as the AO/ASIF and the semi-rigid mini-plates. Compression plates provide absolute inter-fragmentary immobilization and direct primary healing. However, in other studies it has been shown that absolute rigidity and intimate fracture inter-digitations is far from mandatory for adequate bone healing. Compression is not necessary at the fracture site for healing. Use of dynamic compression plates is limited due to their bulky size and demanding techniques of application.

The concept of a semi-rigid fixation is attractive, in that it allows secure fracture fixation with early, readily identifiable bone union and possibly avoidance of stress protection. The type of healing depends not on the stiffness of the plate itself but on the stiffness of the composite of plate, bone and screws at the end of fixation. The use of bone plates and mono-cortical screw system permit a stable semi-rigid fixation that may eliminate the necessity for maxilla mandibular immobilization. Mono-cortical screw and plates are much simpler and highly functional in their use. These plates are smaller in size, easily adaptable and versatile enough to be applied to any fractured site. One of the main advantages of semi rigid fixation is that these plates do not disturb the underlying cortical plate perfusion as much as compression plate. The infection rate with titanium plates has been reported to be 3 % to 23 % [21]. The low infection rate with bone plates is related to the low mobility of fragments. Titanium is an inert material and hence can be used in presence of infections as they provide mechanical immobility which is the principal factor in the success of treatment of mandible fractures. In short, semi-rigid fixation eliminates the need for inter-maxillary fixation, facilitates stable anatomic reduction, and reduces risk of post-operative displacement of fractured fragments allowing immediate return of function [22, 23].

The main disadvantage of bone plate system is that it must be perfectly adapted to the underlying bone to prevent alterations in the alignment of the segments and changes in the occlusal relationship. One of the other disadvantages observed in mini-plate mechanism is the fatigue fracture of the plate. After reduction and fixation, if the gap between the fracture fragments is more than 0.15 mm bone healing will be obscured. This leads to failure of treatment. Accurate position and design of mini-plate are important to neutralize bending and torsion moments during mandibular function.

In order to prevent these failures in fracture treatment, a thorough knowledge about biomechanics of bone, plate and screw is mandatory. Here, FEM study plays an important role. FEM is a numerical method allowing modeling of structures that approximates reality. The spatial geometry model is broken down into large numbers of finite elements which are connected by nodes. When factors such as boundary conditions and loading stress are known, the deformations and tensions of these simple elements can be calculated at each node. Due to their mutual interlinking, displacement and deformation of overall structures can be calculated.

High precision scan of a real patient was obtained. The CT image was done at a thickness of 1.5 mm, thus reliability of the data source was guaranteed. The Dicom file was imported into SLICER software, which reduced the loss and error during the patient information conversion. The proposed model is close to the mandible in reality. The precision of the model was enhanced using a reverse engineering software. The surface optimization and smooth technology simplified the modeling significantly, which can satisfy the need of personalized modeling in the future. As the teeth do not add to the mechanical strength or stiffness of the mandible, limited role of the teeth in mechanical response of the mandible is ignored [4].

High bending moments at the angle caused by bite forces on the incisors pose a challenging problem for any fixation appliance. The ideal plate system must be strong and rigid enough to withstand the functional loads and enable undisturbed fracture healing as during chewing or swallowing, bite forces applied to the mandible result in a complex pattern of bending and torsion moments and shear forces.

Maximum bite force has been demonstrated to be between 300 and 400 N for the average non injured man. Bite forces are reduced during the fracture healing period in patients with mandible fractures. Maximum bite force values are different in the molar, premolar, canine, and incisor regions, with highest bite forces in the molar region and lowest forces in the incisor region. According to Tate et al. [15], the mean incisor bite force within 6 weeks of surgery was found to be 62.8 N. The average bite force in molar region was found to be 119 N.

For body fractures, bite forces result in high bending moments, low torsion moments, and high shear forces [13, 14]. Displacement of the fracture fragments and effects of tension or compression at the site of fracture depend on the distance between loading point and fracture site [12]. The mandible is normally subjected to bending forces at its upper boundary part and to compression forces at its lower boundary part. Bite forces applied close to the fracture result in “negative” bending moments, which give a zone of compression in the alveolar region and a zone of tension at the lower border. Bite forces applied at the other bite points result in “positive” bending moments, with a compression zone at the lower border and a tension zone in the alveolar region [14].

A positive torsion moment resulted in lingual displacement of the border of the fragment posterior to the fracture in combination with buccal displacement of the border of the fragment anterior to the fracture. A negative torsion moment resulted in the opposite effect [14]. For the angle fracture, the maximum value of bending moment was higher than maximum torsion moments. For the body fracture maximum bending and torsion moments were in the same range [14].

The previous two-dimensional model study described that bite points applied on the fractured side always result in compression at the lower border in combination with tension at the alveolar side [19, 24, 25]. In the present study, these moments were the positive bending moments. It was found, however, that all bite points on the fractured side resulted in negative bending moments. The bite points on the non-fractured side resulted in positive bending moments only.

During the fracture healing period, premature failure of the plates must be prevented. The loads transmitted through the plates should not exceed the limit of strength of the material. Ideally, plate fixation should result in undisturbed primary fracture healing. Such healing is only possible if the displacement between the fracture surfaces is within the range of 100–150 μm [3, 26, 27].

In this present study 15 different configurations of mini-plates were considered with different designs. If the fracture segments are within limit value of mobility (150 μm), the internal fixation is sufficiently rigid, the rate of malunion & nonunion is lowered. In our study all measured displacements with the titanium mini-plates were less than 150 μm.

Superior position of straight mini-plate produced better stability. Bridging two mini-plates on both superior and inferior border position appeared to be the most stable solution among the others to prevent torsion moments, because 2 plate system provide greatest stability and neutralize forces applied across the fracture line provide the distance between plates are kept at a maximum. To neutralize torsion moments, regardless of the direction, the application of two bone plates with maximum distance between the plates, is most effective.

Angle fracture and body fracture had relatively high positive bending moments. It has been observed in this study that positive bending moments can be reduced by larger plate in lower border. The AO/ASIF also recommends locating a larger plate on the lower border.

It has been observed that, if the length of middle portion of plate increased or gap between screws increased, gap between fracture segments under bite force also increased. i.e. in ITR5, stability decreased compared to ITR2.

L type mini-plates were placed in the middle of fracture segments in 4 different orientations. All measured mobility was less than 0.15 mm. This study has shown that L mini-plate orientation does not seem to be a primary factor affecting the stability.

In displaced body/angle fracture T plate (ITR12) has given better results compared to X mini-plate. Again comparing ITR13 and ITR14, ITR14 is better than ITR13. The number of screws did not affect the stability considerably. X mini-plate, especially ITR14 can be used as an alternative to 2 mini-plates (ITR3), because of its bracing effect.

Hence, FEM is a suitable tool to evaluate and compare the gap displacement between mandible fragments and to make inferences that will enable more efficient design selection of mini-plates.

Conclusion

We concluded that for a smooth or comminuted fracture, inter-fragmentary stability is less, so the bone plate will have to carry a larger part of the loads across the fracture. For such fractures, the use of two bone plates seems to be recommendable and provided that the distance between them is kept at a maximum. Four hole plate in the lower border is better to prevent torsion moments.

For a single, serrated fracture if that is anatomically repositioned, the inter-fragmentary stability is capable of neutralizing part of the torsion moments, so it seems logical to use one plate for such stable fractures. It must be placed as high as possible. Use of an X type mini-plate can be considered as an alternative to 2 I type mini-plates and provide sufficient stability. It is impossible to measure gap displacement between fracture fragments clinically, but FEM study could determine this numerically.

This was a numerical experiment to identify trends, but clinical application cannot be implied and it varies from case to case.

Contributor Information

Udupikrishna Joshi, Phone: +9448830768, Email: dr_udupijoshi@yahoo.com.

Manju Kurakar, Phone: +9241214997, Email: makurakar13@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Gruss JS, Phillips JH. Complex facial trauma: the evolving role of rigid fixation and immediate bone graft reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1989;1989:93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobar PC. Methods of rigid fixation. Clin Plast Surg. 1992;19:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox T, Kohn MW, Impelluso T. Computerized analysis of Resorbable Polymer plates and screws for the rigid fixation of mandibular angle fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:481–487. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korkmaz HH. Evaluation of different mini-plates in fixation of fractured human mandible with the finite element method. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart RT, Hennebel VV, Thongpreda N, Buskirk WCV, Anderson RC. Modelling the biomechanics of the mandible. A three dimensional finite element study. J Biomech. 1992;25:261–286. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90025-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iseri H, Tekkaya E, Oztan O, Bilgic S. Biomechanical effects of rapid maxillary expansion on the craniofacial skeleton studied by the finite element method. Eur J Orthod. 1998;20:347–356. doi: 10.1093/ejo/20.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Eijden TMGJ, Korfage JAM, Brugma P. Architecture of the human jaw: closing and jaw-opening muscles. Anat Rec. 1997;248:464–474. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199707)248:3<464::AID-AR20>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuong CJ, Borotikar B, Schwartz-Dabney C, Sinn DP. Mechanical characteristics of the mandible after bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy: comparing 2 different fixation techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meijer HJA, Starmans FJM, Bosman F, Sten WHA. A comparison of three finite element models of an edentulous mandible provided with implants. J Oral Rehab. 1993;20:147–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1993.tb01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simsek B, Erkmen E, Yilmaz D, Eser A. Effects of different inter-implant distances on the stress distribution around endosseous implants in posterior mandible: a 3D finite element analysis. Med Eng Phys. 2006;28:199–213. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox Tyler, Kohn MW, Impelluso T. Computerized analysis of resorbable polymer plates and screws for the rigid fixation of mandibular angle fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:481–487. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroon FH, Mathisson M, Cordey JR, et al. The use of mini-plates in mandibular fractures. An invitro study(1991) J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991;19:199–204. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(05)80547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tams J, Van Loon JP, Rozema FR, et al. A three-dimensional study of loads across the fracture for different fracture sites of the mandible. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;34:400–404. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(96)90095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tams J, van Loon J-P, Otten E, et al. A three-dimensional study of bending and torsion moments for different fracture sites of the mandible: an in vitro study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;26:383. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(97)80803-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tate G, Ellis E, III, Throckmorton GS. Bite forces in patients treated for mandibular angle fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:734–736. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theoretical manual-theory reference. Canonsburg: Swanson Analysis Systems; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dichard A, Klotch DW. Testing biomechanical strength of repairs for the mandibular angle fracture. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:201–208. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199402000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champy M, Lodde JP, Jaegar JM, Wilk A, Jerber JC. Mandibular osteosynthesis according to the Michelet Technique. I. Biomechanical basis. II. Presentation of new material. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1976;1976:569–582. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Champy M, Lodde JP. Mandibular synthesis. Placement of the synthesis as a function of mandibular stress. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1976;77:971–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michelet FX, Deymes J, Dessus B. Osteosynthesis with miniaturised screwed plates in maxillofacial surgery. J Maxillofac Surg. 1973;1:79–84. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(73)80017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iizuka T, Lindqvist C, Hallikainen D, Paukku P. Infection after rigid internal fixation of mandibular fractures: a clinical and radiologic study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:585–593. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90340-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alpert B, Gutwald R, Schmelzeisen R. New innovations in craniomaxillofacial fixation: the 2.0 locks system. Keio J Med. 2003;52:120–127. doi: 10.2302/kjm.52.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutwald R, Alpert B, Schmelzeisen R. Principle and stability of locking plates. Keio J Med. 2003;52:21–24. doi: 10.2302/kjm.52.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Champy M, Pape HD, Gerlach KL. Lodde JR Mandibular fractures. In: Kroger E, Schilli W, Worthington P, editors. Oral and Maxillofacial Traumatology. Chicago: Quintessence; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schili W, Luhr HG. Rigid internal fixation by means of compression plates. In: Kroger E, Schilli W, editors. Oral and maxillofacial traumatology. Chicago: Quintessence; 1982. pp. 308–370. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tams J, Van Loon JP, Otten B, Bos RM. A computer study of biodegradable plates for internal fixation of mandibular angle fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;2001:404–407. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.21877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perren SM. Physical and biological aspects of fracture healing with special reference to internal fixation. Clin Orthop. 1979;1979:175–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harada K, Watanabe M, Ohkura K, Enomoto S. Measure of bite force and occlusal contact area before and after bilateral sagittal split rams osteotomy of the mandible using a new pressure-sensitive device. A preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:370–373. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(00)90913-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]