Abstract

We have investigated the expression of heme oxygenase (HO) in the rat kidney and the effects of HO-dependent heme metabolites on the apical 70-pS K+ channel in the thick ascending limb (TAL). Reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) and Western blot analyses indicate expression of the constitutive HO form, HO-2, in the rat cortex and outer medulla. Patch-clamping showed that application of 10 μM chromium mesoporphyrin (CrMP), an inhibitor of HO, reversibly reduced the activity of the apical 70-pS K+ channel, defined by NPo, to 26% of the control value. In contrast, addition of 10 μM magnesium protoporphyrin had no significant effect on channel activity. HO involvement in regulation of the apical 70-pS K+ channel of the TAL, was further indicated by the addition of 10 μM heme-L-lysinate, which significantly stimulated the channel activity in cell-attached patches by 98%. The stimulatory effect of heme on channel activity was also observed in inside-out patches in the presence of 0.5–1 mM reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. This was completely abolished by 10 μM CrMP, suggesting that a HO-dependent metabolite of heme mediated the effect. This was further supported by exposure of the cytosolic membrane of inside-out patches to a carbon monoxide–bubbled bath solution, which increased channel activity. Moreover, carbon monoxide completely abolished the effect of 10 μM CrMP on the channel activity. In contrast, 10 μM biliverdin, another HO-dependent metabolite of heme, had no effect. We conclude that carbon monoxide produced from heme via an HO-dependent metabolic pathway stimulates the apical 70-pS K+ channel in the rat TAL.

Introduction

The apical K+ channel in the thick ascending limb (TAL) plays a key role in maintaining the function of the Na/K/Cl cotransporter. Inhibition of the apical K+ channels has been shown to reduce NaCl reabsorption in the TAL (1–3). Three types of K+ channels — the low-conductance (30 pS), intermediate-conductance (70 pS), and Ca2+-activated maxi K+ channel (127 pS) — have been found in the apical membrane of the TAL (1, 4–7). It is well established, however, that the 30-pS and 70-pS K+ channels are mainly responsible for K+ recycling across the apical membrane (1). Moreover, a previous study (8) has revealed that the 70-pS K+ channel contributes ∼70–80% of the apical K+ conductance.

The activity of the 70-pS K+ channel is regulated by several signal transduction pathways (8–11). We have shown previously (9) that cytochrome P450–dependent metabolites of arachidonic acid inhibited channel activity. In contrast, nitric oxide (NO) stimulates the 70-pS K+ channel via a pathway dependent on (CrMP) (11).

Given that both NO synthase (NOS) and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase are hemoproteins, degradation of NOS and P450 monooxygenase is controlled by the activity of heme oxygenase (HO) (12). HO converts heme molecules to biliverdin, carbon monoxide (CO), and the chelated iron by oxidative cleavage (12). A large body of evidence has demonstrated that CO is not only a stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase (13, 14) but also can directly modulate a variety of molecules including ion channels (15–17). In the present study, we explore the role of HO system–dependent heme metabolites in the regulation of the apical K+ channels in the TAL.

Methods

Isolation of TAL.

We have used pathogen-free Sprague-Dawley rats (either sex) purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, New York, USA). Animals were maintained on a high-potassium diet for at least 1 week, as dissection is easier in animals on a high-potassium diet than in those on a normal chow. The average weight of the animals was 100–120 g before use. The animals were sacrificed by decapitation, and the kidneys were immediately removed. After the capsule was removed, the middle section of the kidney was cut with a razor blade into several 1.0-mm-thick slices. The cortical and medullary TAL tubules were dissected in HEPES-buffered NaCl Ringer solution containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.8 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH) at 22°C and transferred onto a 5 mm × 5 mm cover glass coated with Cell-Tak (Collaborative Research, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA) to immobilize the tubules. The glass was placed in a chamber mounted on an inverted microscope (Nikon Inc., Melville, New York, USA), and the tubule was superfused with HEPES-buffered NaCl solutions. The tubule was cut open with a sharpened pipette to expose the apical membrane. The temperature of the 1,000-μl chamber was maintained at 37 ± 1°C by circulating warm water around the chamber.

Patch-clamp technique.

Patch electrodes were pulled from a vertical pipette puller model PP-83; (Narishige Scientific Instrument Laboratory Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) in two stages with borosilicate glass capillaries (Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). The pipettes were fire-polished and had resistances of 4–6 MΩ when filled with 140 mM KCl. Recordings were made with an EPC-7 patch-clamp amplifier, and single-channel currents were low-pass filtered at 1 kHz with an eight-pole Bessel filter (model 902LPF; Frequency Devices, Haverhill, Massachusetts, USA). The recordings were digitized at a sampling rate of 44 kHz with a modified Sony PCM-501ES pulse code modulator (Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan)and stored on videotape (Sony SL-2700; Sony Corp.). For analysis, the data were collected to an IBM-compatible 586 computer at a rate of 5 kHz and analyzed with the use of the pCLAMP software system 6.04 (Axon Instrument, Burlingame, California, USA).

We defined NPo as an index for determining channel activity in these patches with multiple channels, and no efforts were made to examine whether the alteration of channel activity resulted from an increase in channel number (N) or open probability (Po). The NPo was determined from data samples of 1-min duration as follows: NPo = (t1 + t2 +...tn), where t1, t2, and tn were the ratios between the time observing open channel current and the total time of measurement at each of the current levels. The slope conductance of the channel was determined by measurement of channel current at three different membrane potentials.

RT-PCR of HO-2.

For reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR), total RNA (200 ng/PCR reaction) from rat kidney was reverse-transcribed using oligo-dT priming. PCR amplification was performed in a PTC-100 programmable thermal controller (MJ Research Inc., Watertown, Massachusetts, USA), using 30 cycles of denaturation (92°C, 2 min), annealing (54°C, 1 min), and extension (72°C, 1 min). The buffer conditions for primer pairs were optimized with RT-treated RNA, using the Opti-Prime buffer system and Taq polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, California, USA). The primer pair used for PCR (sense primer: 5′-CAGCAACAATGTCTTCAGAGG-3′; antisense primer: 5′-AGTAAAGTGCAGTGGTGGCC-3′) amplifies nucleotides 172–402 of rat HO-2 (GenBank accession no. J05405); these primers anneal to separate exons in the rat HO-2 gene (GenBank accession no. U05013).

Western blotting.

Western blots of kidney microsomal membranes were performed using a commercial HO-2 antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, California, USA). This antibody is specific for amino acids 246–264 of human HO-2; X/19 amino acids are conserved in rat HO-2; and this peptide has no homology to the rat HO-1 or HO-3 proteins. For isolation of microsomal protein, rat kidney (Sprague-Dawley) was dissected, homogenized in nine volumes of ice-cold homogenization buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 5 mM Tris, and 2 mM EDTA [pH 7.5], plus protease inhibitors), and centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was subsequently centrifuged at 100,000 g at 4°C for 30 min, followed by resuspension of the pellet in homogenization buffer. Microsomal protein (100–150 μg) was resolved by gel electrophoresis in 15% SDS–polyacrylamide and transferred in 25 mM Tris-HCl, 192 mM glycine, 25% methanol to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Antigen–antibody complexes were viewed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Life Sciences, Arlington Heights, Illinois, USA). For immunoabsorption, antibody was incubated with 5 μg of a lysate of Escherichia coli cells expressing recombinant rat HO-2 protein (StressGen Biotechnologies Corp., Victoria, British Columbia, Canada).

Experimental solutions and statistics.

The pipette solution contained (in mM) 140 KCl, 1.8 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.40). The bath solution for cell-attached patches was composed of (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.8 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). The composition of the bath solution for inside-out patches was the same as that for the cell-attached patches, except that free Ca2+ was 100 nM. Nw-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine were purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp. (La Jolla, California, USA). CrMP, magnesium protoporphyrin (MgPP), hemin, and biliverdin were purchased from Porphyrin Products (Logan, Utah, USA). CrMP, MgPP, and biliverdin stock solutions (15 mM) were prepared in 50 mM Na2CO3 and were added to the bath to reach the designed concentration. Heme-L-lysinate stock solution (1 ml) contained 38 mM hemin, 142 mM L-lysine, 550 μl H2O, 400 μl propylene glycol, and 50 μl ethanol. We also made a control vehicle solution, which had the same composition but without hemin. The vehicle solution had no significant effect on the channel activity. CO was purchased from Tech Air (White Plains, New York, USA). CO solution was prepared as described by Wang et al. (16). Briefly, 20 ml stock solution in a sealed glass container was bubbled with a stream of pure CO (99.999%) for 20 min at 100 kPa and room temperature. In this CO-saturated solution, 1 μl contains ∼30 ng of the gas. The stock solution of CO was prepared freshly before each experiment and then diluted immediately to desired concentrations with bath solution. The pH of the CO-containing bath solution was 7.40.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM, and a paired Student’s t test was used to determine the significance between the control and experimental period. Statistical significance was taken as P < 0.05.

Results

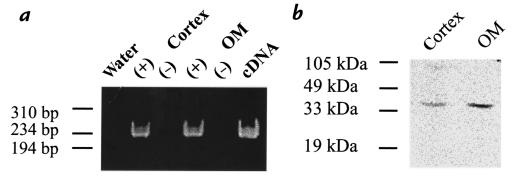

We first used HO-2–specific primers to examine whether HO-2 was expressed in the kidney. Figure 1a shows that a band of RT-PCR product with an expected size of 230 bp was detected in the rat kidney cortex and outer medulla on an ethidium bromide–stained agarose gel. Sequence analysis further confirmed that this 230-bp RT-PCR product was HO-2 (data not shown). The expression of HO-2 in the kidney was also confirmed by Western analysis. Figure 1b shows a representative Western blot demonstrating immunoreaction to a polyclonal antibody for HO-2. It is apparent that the antibody detected a band of 36 kDa in microsomal membranes from rat cortex and outer medulla (Figure 1b). This reactivity was abolished by preabsorption with recombinant HO-2 protein (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Expression of HO-2 in rat kidney cortex and outer medulla (OM). (a) RT-PCR of rat kidney using primers specific for HO-2. An ethidium-stained 6% polyacrylamide gel is displayed; one-fifth of each PCR reaction was loaded per lane. A 230-bp fragment was amplified in rat cortex and outer medulla. Water and RT(–) controls are negative. (b) Western blotting of rat kidney, using an HO-2–specific antibody. RT, reverse transcriptase.

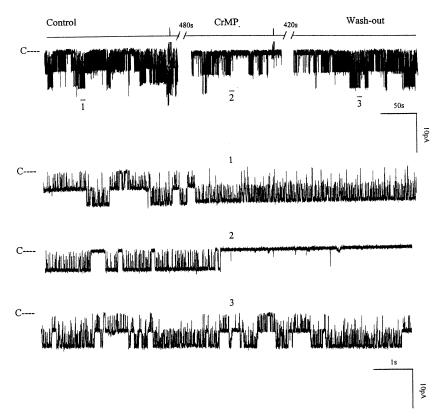

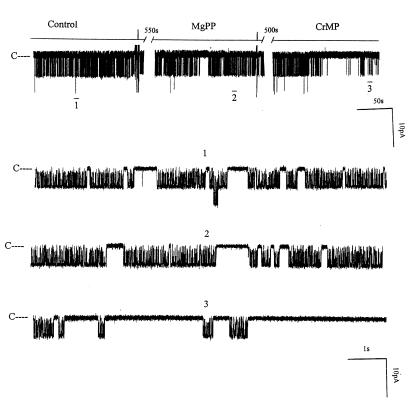

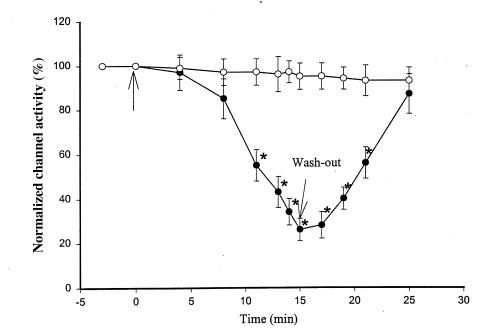

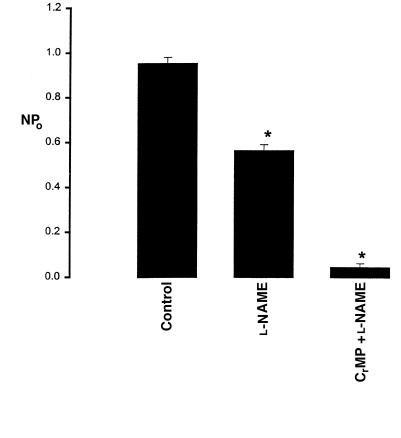

After confirming the presence of HO-2 in the rat kidney, we investigated the role of HO in the regulation of the 70-pS K+ channel. Figure 2 is a representative recording demonstrating the effect on the 70-pS K+ channel in a cell-attached patch of 10 μM CrMP, an inhibitor of HO (18). It is apparent that addition of CrMP reversibly decreased channel activity. In 11 experiments, addition of 10 μM CrMP reduced the channel activity to 26 ± 4% of the control value, from 0.95 ± 0.10 to 0.25 ± 0.03 (P < 0.01). To exclude the possibility that CrMP is a channel blocker, we examined the effect of CrMP on the 70-pS K+ channel in inside-out patches. Addition of 10–30 μM CrMP had no effect on the activity of the 70-pS K+ channel (n = 4, data not shown). That the effect of CrMP was the result of inhibiting HO was further supported by experiments in which addition of MgPP, an analogue that does not inhibit HO at a concentration of 10 μM (19), failed to reduce channel activity (Figure 3). In contrast, in the presence of MgPP, addition of 10 μM CrMP inhibited the apical 70-pS K+ channel (Figure 3). Figure 4 summarizes the results obtained from 11 experiments: 10 μM CrMP reduced the channel activity by 74 ± 5%, from 0.95 ± 0.10 to 0.25 ± 0.03 within 15 minutes. In contrast, addition of 10–30 μM MgPP had no significant effect on channel activity, as NPo (0.93 ± 0.10, n = 8) in the presence of MgPP is not significantly different from the control value. This indicates that effect of CrMP was due to inhibition of HO in the TAL. The 70-pS K+ channel has been shown to be stimulated by the NO-cGMP–dependent pathway (11). To exclude the possibility that the effect of CrMP is the result of decreasing NO generation, we explored the effect of CrMP in the presence of L-NAME, an agent that blocks NO synthesis. Figure 5 summarizes the results, showing the effect of 10 μM CrMP on channel activity in cell-attached patches in the presence of 200 μM L-NAME. Addition of L-NAME significantly reduced NPo from the control value of 0.95 ± 0.5 to 0.55 ± 0.5 (n = 4). Moreover, application of 10 μM CrMP further diminished the channel activity by 90 ± 10% and decreased NPo to 0.05 ± 0.02 (n = 4, P < 0.01), indicating that the inhibitory effect of CrMP is independent from the NO generation.

Figure 2.

A channel recording showing the effect of 10 μM CrMP on the activity of the 70-pS K+ channel in a cell-attached patch. The channel-closed level is indicated by C, and the pipette holding potential was 0 mV. The top trace shows the time course of the effect of CrMP. Three parts of the trace, indicated by numbers 1–3, are extended at fast time resolution. CrMP, chromium mesoporphyrin.

Figure 3.

A channel recording demonstrating effects of 10 μM MgPP and CrMP on the 70-pS K+ channel in a cell-attached patch. The top trace shows the time course of the effects of MgPP and CrMP. Three parts of the trace, indicated by numbers 1–3, are extended at a fast time scale. The pipette holding potential was 0 mV. MgPP, magnesium protoporphyrin.

Figure 4.

Effects of 10 mM MgPP (open circles; n = 8) and CrMP (filled circles; n = 11) on the activity of the 70-pS K+ channel. The arrow indicates where MgPP or CrMP was added. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *Significantly different from the control value (P < 0.01).

Figure 5.

The effect of CrMP on the channel activity in the presence of 200 μM L-NAME (n = 4). The experiments were performed in cell-attached patches. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. NPo was determined as described in Methods. *Significantly different from the control value (P < 0.01). L-NAME, Nw-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester.

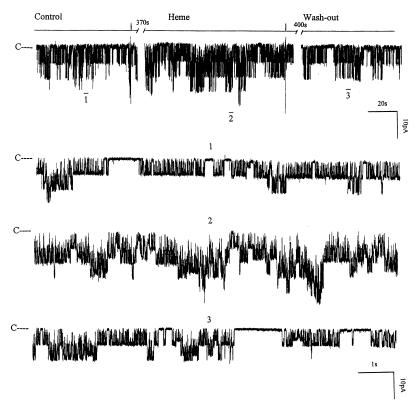

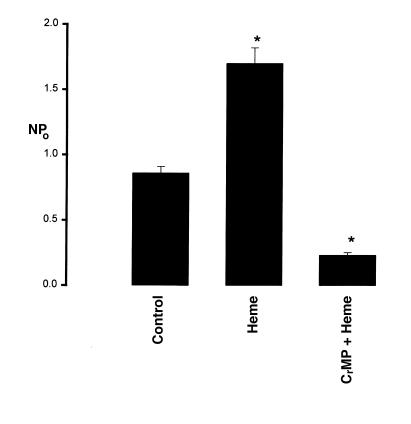

After establishing that HO participated in regulating the apical K+ channels in the TAL, we explored the mechanism by which HO modified the channel activity. If a decrease in HO-dependent heme metabolites was responsible for reducing channel activity, application of substrates of HO, such as heme-containing molecule, should enhance the channel activity. We used heme-L-lysinate to increase HO-dependent heme metabolism. Figure 6 is a representative recording showing that addition of 10 μM heme-L-lysinate increased the channel activity in cell-attached patches by 98 ± 9%, from 0.86 ± 0.06 to 1.70 ± 0.12 (n = 10, P < 0.01) (Figure 7). The stimulatory effect of heme-L-lysinate was reversible, as the channel activity returned to the original level after washout. The effect of heme was not direct because the stimulatory effect of heme-L-lysinate was not observed in inside-out patches, indicating that the effect of heme was the result of increasing HO-dependent metabolites. This notion was further supported by observations that addition of 10 μM CrMP abolished the stimulatory effect of heme-L-lysinate on channel activity in cell-attached patches (Figure 7). In seven experiments, we observed that 10 μM CrMP not only abolished the stimulatory effect of heme-L-lysinate but also decreased channel activity from 1.70 ± 0.12 to 0.24 ± 0.02 (P < 0.01).

Figure 6.

The effect of 10 μM heme-L-lysinate (Heme) on the channel activity in a cell-attached patch. The time course of experiments is shown on the top trace of the figure. Three parts of the trace, indicated by numbers 1–3, are extended at fast time resolution. The channel-closed level is indicated by C, and the pipette holding potential was –20 mV.

Figure 7.

The effect of 10 μM heme-L-lysinate (Heme), or heme-L-lysinate + 10 μM CrMP, on NPo of the 70-pS K+ channel. The observation numbers are 10 and 7, respectively. Experiments were carried out in cell-attached patches. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. NPo was determined as described in Methods. *Significantly different from the control value (P < 0.01).

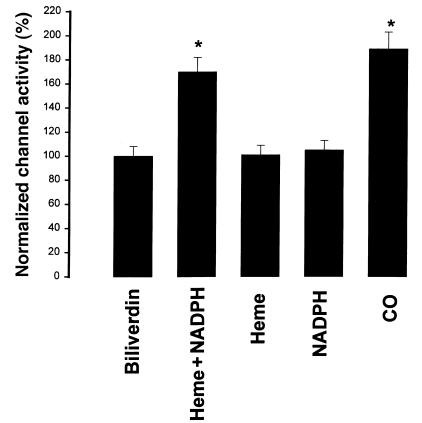

It is known that HO-dependent heme metabolism requires the presence of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). To determine whether the absence of the stimulatory effect of heme-L-lysinate in excised patches was due to lack of NADPH, we examined the effect of heme-L-lysinate on the channel activity in inside-out patches in the presence of 0.5–1 mM NADPH (Figure 8). It is apparent that heme-L-lysinate alone had no significant effect on the 70-pS K+ channel activity in inside-out patches. However, addition of 0.5–1 mM NADPH increased channel activity by 79 ± 16% (Figure 9), suggesting that the effect of heme-L-lysinate is the result of HO-dependent heme metabolism. To exclude the possibility that NADPH may directly stimulate the 70-pS K+ channel, we examined the effect of 1 mM NADPH on channel activity without heme-L-lysinate. Addition of NADPH alone had no significant effect on the channel activity in the absence of heme-L-lysinate (Figure 9). That the effect of heme plus NADPH is mediated by HO-dependent heme metabolites is further supported by experiments in which CrMP abolished the effect of heme (data not shown).

Figure 8.

A channel recording showing the effect of 10 μM heme-L-lysinate (Heme) and 0.5–1 mM NADPH on the activity of the 70-S K+ channel in an inside-out patch. The channel-closed level is indicated by C, and the pipette holding potential was –20 mV. The top trace is the time course of experiments. Three parts of the trace, indicated by numbers 1–3, are extended at a fast time resolution. NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

Figure 9.

Effects of 10 μM biliverdin (n = 3), 10 μM heme-L-lysinate + 0.5-1 mM NADPH (n = 8), 10 μM heme-L-lysinate (n = 5), 1 mM NADPH (n = 8), and 100 μM CO (n = 8) on the activity of the 70-pS K+ channel. Experiments were carried out in inside-out patches. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *Significantly different from the control value (P < 0.05).

HO cleaves heme into chelated iron, biliverdin, and CO (12). We examined which product of the HO-dependent heme metabolic pathway mediates the effect of heme. We investigated the effect of 10 μM biliverdin on the 70-pS K+ channel in inside-out patches. Figure 9 shows that 10 μM biliverdin had no significant effect on channel activity. We next explored whether CO was responsible for mediating the effect of heme on the activity of 70-pS K+ channels in the TAL. Figure 10 shows a representative recording demonstrating the effect of CO on the activity of the 70-pS K+ channel in an inside-out patch. When the internal surface of the patch membrane was exposed to the bath solution containing ∼100 μM of CO, the activity of the 70-pS K+ channel significantly increased. Figure 9 summarizes the results obtained from eight experiments in which the effect of CO was examined. CO increased NPo of the 70-pS K+ channel by 90 ± 8%. Also, Figure 10 demonstrates that the effect of CO was reversible. When the bath solution was changed to the CO-free bath solution, the channel activity returned to the control level. This indicates that CO mediates the effect of HO-dependent heme metabolism on channel activity. This notion is further supported by experiments in which exposure of the cell to CO in cell-attached patches completely abolished the effect of 10 μM CrMP (Figure 11). Addition of CrMP reduced channel activity to 28 ± 5% of the control value, from 0.6 ± 0.10 to 0.17 ± 0.02 (n = 3, P < 0.05). Superfusion of the cell with 100 μM CO-containing bath solution not only completely restored the channel activity but also increased NPo to 0.78 ± 0.09, a 30% increase in comparison with the control value (P < 0.05).

Figure 10.

The experiment was performed in an inside-out patch to demonstrate the effect of 100 μM CO on the channel activity. The top trace shows the time course of the experiment. Three parts of the trace, indicated by numbers 1–3, are extended to demonstrate the detail of channel activity. The pipette holding potential was 0 mV.

Figure 11.

A channel recording showing the effect of CO (100 μM) and 10 μM CrMP on the activity of the 70-pS K+ channel in a cell-attached patch. The channel-closed level is indicated by C, and the pipette holding potential was –50 mV. The top trace shows the time course of the experiment. Three parts of the trace, indicated by numbers 1–3, are extended at fast time resolution. The activity of the small-conductance K+ channel is also visible in trace 1.

Discussion

HO plays a key role in maintaining cellular heme homeostasis and hemoprotein level by oxidative cleavage of the heme ring to produce biliverdin, iron, and CO (12). A large body of evidence suggests that the HO-dependent system is as important as the NOS-dependent system and is involved in a variety of cell functions (14, 15, 17, 20, 21). Two types of HO, the inducible form (HO-1) and the constitutive form (HO-2), are expressed in a variety of cells. HO-2 is highly expressed in neuronal tissues, and its location closely resembles that of soluble guanylyl cyclase (22). It has been demonstrated that cGMP elevation produced by electrical field stimulation was significantly diminished in HO-2 knockout mice (23). Moreover, HO-2 is highly expressed in the endothelium and adventitial nerve of blood vessels and is involved in the regulation of dilating blood vessels (24). Also, HO-2 is involved in the regulation of intestinal relaxation (24). The present study indicates that HO-2 is present in the rat kidney. Recent immunocytochemical studies found the expression of HO-2 in the TAL of mouse kidney (Mount, D.B., et al., unpublished observations). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that HO-1 is also expressed in the TAL. Therefore, the response to the manipulation of the HO-dependent heme metabolism may be the result of changing the activity of both HO-1 and HO-2. To determine the role of HO-1 and HO-2 in regulating the apical K+ channels in the TAL, more experiments, including using HO-1 or HO-2 knockout mice, are required.

The present study indicates that renal HO plays an important role in the regulation of the apical K+ channels in the TAL. First, inhibition of HO with CrMP reduces channel activity. In contrast, MgPP, a weak inhibitor of HO, has no significant effect. That the effect of CrMP is the result of inhibiting HO is strongly indicated by the observation that CO can reverse the CrMP-induced inhibition. Second, addition of heme-L-lysinate increases the channel activity in cell-attached patches. Finally, heme can also stimulate the 70-pS K+ channel in inside-out patches in the presence of NADPH, which is required for the oxidative reaction of HO. Inasmuch as K+ recycling is important for the normal function of Na/K/Cl cotransporter, it is conceivable that the HO system plays an important role in the regulation of NaCl transport in the TAL.

There are at least two mechanisms by which HO may regulate Na+ transport in the TAL. First, the HO system can have a chronic effect on Na+ transport by changing intracellular concentrations of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase or NOS. Second, the HO system can have an acute effect via HO-dependent heme metabolites, such as CO. It is well established that cytochrome P450 monooxygenase plays a key role in the regulation of Na+ transport in the TAL (10, 25, 26). Moreover, a large body of evidence indicates that the NO system is important in the regulation of the tubule function in the kidney (27). Thus, the activity of the HO system can influence NaCl transport in the TAL by controlling the degradation of both P450 monooxygenase and NOS. However, this possibility is not likely to be responsible for the effect of inhibiting the HO system observed in the present study because the effect of CrMP is acute. Therefore, the second mechanism is most likely to be involved in mediating the effect of inhibiting HO. This notion is also supported by observations that addition of heme-L-lysinate activates the 70-pS K+ channel. Moreover, two lines of evidence indicate that CO mediates the effect of HO-dependent heme metabolites on the 70-pS K+ channel: (a) CO can mimic the stimulatory effect of heme-L-lysinate, and (b) CO completely abolished the inhibitory effect of CrMP. In contrast, addition of biliverdin had no significant effect on channel activity. Although the nominal concentration of CO used in the present study was ∼100 μM, the actual concentration should be significantly lower than 100 μM, as CO would be evaporated from the bath solution as soon as it flowed from a sealed container to the opened perfusion chamber. In addition, if HO is present in the close vicinity of the apical K+ channels, the local concentration of endogenous CO might reach a high enough level to activate the apical K+ channels in the TAL.

The TAL reabsorbs the 20–25% of the filtered Na+ load and plays a key role in the urinary concentrating mechanism (2, 3). The transcellular Na+ reabsorption in the TAL takes place by two steps: Na+ and Cl– enter the cell across the luminal membrane through the Na/K/Cl cotransporter; Na+ is then extruded from the cell via Na-K-ATPase, and Cl– diffuses across the basolateral membrane through the Cl– channel and KCl transporter (2, 3). The apical K+ channels are involved in K+ recycling that serves at least three functions. First, K+ recycling participates in generating the lumen-positive transepithelial potential, which is the driving force for transepithelial Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ reabsorption. Second, K+ recycling provides an adequate supply to the Na/K/Cl cotransporter in the cTAL. Third, K+ recycling maintains the diffusing potential of Cl– across the basolateral membrane and, accordingly, keeps the flow of Cl– current. The importance of K+ recycling is best demonstrated by the recent genetic study (28) in which a defective gene product encoding ROMK channel, a renal K+ channel that is the key component of the apical K+ channels in the TAL, resulted in an abnormal salt transport in human.

Three types of K+ channels — 30 pS, 70 pS, and maxi K+ (127 pS) — have been found in the apical membrane of the TAL (4, 6, 7). The Ca2+-activated maxi K+ channel is unlikely to play an important role in K+ recycling because the maxi K+ channel has a low Po under physiological conditions. Therefore, the 30-pS and 70-pS K+ channels are mainly responsible for the apical K+ conductance and K+ recycling (1). We have shown previously (8) that the 70-pS K+ channel has a higher channel density than the 30-pS K+ channel. Moreover, the 70-pS K+ channel has high channel Po (0.6). Thus, it is estimated that the 70-pS K+ channel contributes two-thirds of the apical K+ conductance in the rat TAL (8).

In the present study, we have shown that CO may potentially be an important regulator of the 70-pS K+ channel in the TAL. CO is formed in a variety of cells, including neuron and endothelial cells, under normal conditions (12). Recently, a large body of evidence indicates that CO plays an important role in the regulation of blood pressure (17, 29) and is involved in energy metabolism and synaptic transmission (15). CO has been shown to stimulate the Ca2+-activated K+ channel in smooth muscle cells (16).

The mechanism by which CO stimulates the 70-pS K+ channel has not been explored in the present study. There are at least three mechanisms by which CO can modify the channel activity. First, CO has been shown to activate soluble guanylate cyclase and increase cGMP production (13, 14). Inasmuch as cGMP can increase the channel activity (11), it is possible that in cell-attached patches, the effect of CO may partially be mediated by a cGMP-dependent pathway. Second, CO may inhibit the activity of cytochrome p450 monooxygenase and, accordingly, reduce the production of the p450-dependent metabolites of arachidonic acid that block the 70-pS K+ channel. Indeed, CO has been demonstrated to interact with cytochrome P450 in the ductus arterius of lamb (30, 31). Third, CO may directly activate the 70-pS K+ channel. Redox has been shown to play an important role in the regulation of ion channels (32). It is possible that the direct effect of CO is the result of changing redox potential. However, this possibility is not supported by our unpublished observations that adding dithiothreitol or NO donors such as S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine and sodium nitroprusside, agents that have been shown to change redox potential, has no effect on channel activity in excised patches. We need further experiments to explore the mechanisms by which CO regulates the apical 70-pS K+ channel in the TAL.

We conclude that HO-2 is expressed in the rat kidney and that endogenous CO plays an important role in stimulation of the apical 70-pS K+ channel in the rat TAL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Melody Steinberg for editorial assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants ROIDK-47402 (to W.H. Wang), PO1HL34300) (to A. Nasjletti and W.H. Wang), and HL-18579 (to A. Nasjletti).

References

- 1.Wang WH, Hebert SC, Giebisch G. Renal K channels: structure and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:413–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greger R. Ion transport mechanisms in thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop of mammalian nephron. Physiol Rev. 1985;65:760–797. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1985.65.3.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebert SC, Andreoli TE. Control of NaCl transport in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:F745–F756. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1984.246.6.F745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleich M, Schlatter E, Greger R. The luminal K+ channel of the thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop. Pflugers Arch. 1990;415:449–460. doi: 10.1007/BF00373623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang WH, White S, Geibel J, Giebisch G. A potassium channel in the apical membrane of rabbit thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F244–F253. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.2.F244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang WH. Two types of K+ channel in thick ascending limb of rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F599–F605. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.4.F599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taniguchi J, Guggino WB. Membrane stretch: a physiological stimulator of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:F347–F352. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.3.F347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu M, Zhu Y, Balazy M, Falck JR, Wang WH. Effect of angiotensin II on the apical K+ channels in the thick ascending limb of the rat kidney. J Gen Physiol. 1996;108:537–547. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.6.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang WH, Lu M. Effect of arachidonic acid on activity of the apical K channel in the thick ascending limb of the rat kidney. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:727–743. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.4.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang WH, Lu M, Hebert SC. Cytochrome P-450 metabolites mediate extracellular Ca2+-induced inhibition of apical K+ channels in the TAL. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C103–C111. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu M, Wang XH, Wang WH. Nitric oxide increases the activity of the apical 70 pS K+ channel in TAL of rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F946–F950. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.5.F946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maines MD. The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobbs AJ. Soluble guanylate cyclase: the forgotten sibling. Trends Pharmacol. 1997;18:484–491. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingi T, Cheng J, Ronnett GV. Carbon monoxide: an endogenous modulator of the nitric oxide-cyclic GMP signaling system. Neuron. 1996;16:835–842. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nathanson JA, Scavone C, Scanlon C, McKee M. The cellular Na+ pump as a site of action for carbon monoxide and glutamate: a mechanism for long-term modulation of cellular activity. Neuron. 1995;14:781–794. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang R, Wu L, Wang Z. The direct effect of carbon monoxide on KCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 1997;434:285–291. doi: 10.1007/s004240050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson RA, Lavesa M, Askari B, Abraham NG, Nasjletti A. A heme oxygenase product, presumably carbon monoxide, mediates a vasodepressor function in rats. Hypertension. 1995;25:166–169. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vreman HJ, Ekstrand BC, Stevenson DK. Selection of metalloporphyrin heme oxygenase inhibitors based on potency and photoreactivity. Pediatr Res. 1993;33:195–200. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199302000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drummond GS, Rosenberg DW, Kappas A. Intestinal heme oxygenase inhibition and increased biliary iron excretion by metalloporphyrins. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1170–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seki T, et al. Interrelation between nitric oxide synthase and heme oxygenase in rat endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;331:87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson RA, Lavesa M, DeSeyn K, Scholer MJ, Nasjletti A. Heme oxygenase substrates acutely lower blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1132–H1138. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verma A, Hirsch DJ, Glatt CE, Ronnett GV, Snyder SH. Carbon monoxide: a putative neural messenger. Science. 1993;259:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.7678352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zakhary R, et al. Targeted gene deletion of heme oxygenase 2 reveals a neural role for carbon monoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14848–14853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zakhary R, et al. Heme oxygenase 2: endothelial and neuronal localization and role in endothelium-dependent relaxation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:795–798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escalante B, Erlij D, Falck JR, McGiff JC. Effect of cytochrome P450 arachidonate metabolites on ion transport in rabbit kidney loop of Henle. Science. 1991;251:799–802. doi: 10.1126/science.1846705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amlal H, et al. ANG II controls Na+-K+(NH4+)-2Cl- cotransport via 20-HETE and PKC in medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1047–C1056. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.4.C1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kone BC, Baylis C. Biosynthesis and homeostatic roles of nitric oxide in the human kidney. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F561–F578. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.5.F561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon DB, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of Bartter’s syndrome revealed by mutations in the K channel, ROMK. Nat Genet. 1996;14:152–156. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozma F, Johnson RA, Nasjletti A. Role of carbon monoxide in heme-induced vasodilation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;323:R1–R2. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coceani F, Kelsey L, Seidlitz E. Carbon monoxide-induced relaxation of the ductus arteriosus in the lamb: evidence against the prime role of guanylyl cyclase. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1689–1696. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coceani F, et al. Carbon monoxide formation in the ductus arteriosus in the lamb: implications for the regulation of muscle tone. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:599–608. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stamler JS. Redox signaling: nitrosylation and related target interactions of nitric oxide. Cell. 1994;78:931–936. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]