Abstract

Alcohol can disrupt goal-directed behavior by impairing the ability to inhibit attentional shifts towards salient but goal-irrelevant stimuli. Individuals who are highly sensitive to this effect of the drug may be at increased risk for problematic drinking, especially among those whose attention is drawn to alcohol-related cues in the environment (i.e., attentional bias). The current study examined the acute impairing effect of alcohol on inhibitory mechanisms of attentional control in a group of healthy social drinkers. We then examined whether increased sensitivity to this disinhibiting effect of alcohol was associated with heavy drinking, especially among those who have an attentional bias towards alcohol-related stimuli. Eighty nondependent social drinkers performed a delayed ocular response task that measured their inhibitory control of attention by their ability to suppress attentional shifts to irrelevant stimuli. Attentional bias was measured using a visual probe task. Inhibitory control was assessed following a moderate dose of alcohol (0.64 g/kg) and a placebo. Participants made more inhibitory failures (i.e., premature saccades) following 0.64 g/kg alcohol compared with placebo and the relation of this effect to their drinking habits did depend on the level of the drinker’s attentional bias to alcohol-related stimuli. Among drinkers with higher attentional bias, greater impairment of inhibitory control was associated with heavier drinking. In contrast, drinkers with little or no attentional bias showed no relation between their sensitivity to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol and drinking habits. These findings have implications for understanding how heightened incentive-salience of alcohol cues and impaired attentional control can interactively contribute to excessive alcohol use.

Keywords: Inhibitory control, attentional bias, alcohol effects, delayed ocular response task, abuse potential

Impulsivity has long been considered a risk factor for harmful alcohol use. Advances in neurocognitive models of impulse control have allowed substance abuse researchers to understand how dysfunction of specific cognitive mechanisms underlying behavioral control can contribute to substance use (Fillmore, 2003; Jentsch & Taylor, 1999; Lyvers, 2000). Several theories of human behavior propose that behavioral control can be understood as two conflicting mechanisms: inhibitory and activational (Fowles, 1987; Logan, Cowan, & Davis, 1984). The activational process is responsible for executing behavior, whereas the inhibitory process is responsible for suppressing inappropriate or unwanted behavior. An imbalance of these countervailing systems (e.g., impaired inhibitory control and heightened approach tendency) can result in impulsive action, such as consuming alcohol when doing so is maladaptive.

Research on the acute effects of alcohol has shown that alcohol can increase impulsive behavior by impairing drinkers’ ability to inhibit prepotent actions. For example, numerous studies using laboratory models of inhibitory control have shown that alcohol can reduce drinkers’ ability to quickly inhibit a behavioral impulse (e.g., de Wit, Crean, & Richards, 2000; Mulvihill, Skilling, & Vogel-Sprott, 1997). These studies also show that inhibitory processes are more susceptible to the disruptive effects of alcohol than are activational processes. Thus, intoxicated drinkers may find their ability to inhibit behavioral impulses compromised to a greater extent than their ability to activate responses (Fillmore, 2003). As a result, as drinkers consume alcohol and become more intoxicated, they become less able to inhibit further alcohol consumption.

If acute alcohol impairment of inhibitory control promotes excessive alcohol consumption, then one would expect that drinkers who are highly sensitive to this alcohol effect would be at higher risk for harmful drinking. Our group (Weafer & Fillmore, 2008) examined the degree to which individual differences in alcohol impairment of inhibitory control was associated with drinking behavior. We found that drinkers who became more disinhibited following a moderate dose of alcohol (0.64 g/kg) consumed more alcohol when given ad libitum access to beer. Interestingly, baseline levels of inhibitory control were not associated with alcohol consumption, suggesting that the effect was specific to the degree to which inhibitory control was impaired under alcohol. A similar study using an animal model showed that rats that were most sensitive to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol consumed the most alcohol when given ad libitum access (Poulos, Parker, & Le, 1998). Taken together, these findings support the notion that individual differences in sensitivity to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol may influence drinking behavior.

All of the previous research examining how alcohol-induced impairments of inhibitory control can contribute to excessive use has focused on the inhibition of manual action; however, research in the cognitive sciences has identified separate cognitive mechanisms that govern the inhibitory control of attention (Posner & Petersen, 1990; Tipper, 1985). These inhibitory mechanisms are important for selective attention, especially in situations where people must direct attention away from salient but goal-irrelevant stimuli in the environment. Inhibitory control of attention can be measured in the laboratory using delayed-looking paradigms such as the delayed ocular response task (DORT). This task assesses inhibitory control of attention by measuring participants’ ability to inhibit a reflexive attentional shift towards a visual distracter presented in the periphery. Although the presentation of such a stimulus would typically elicit a reflexive shift in attention towards its location (Peterson, Kramer, & Irwin, 2004), participants are instructed to maintain their gaze on a central fixation point. Participants with poor attentional control typically have more difficulty ignoring the distracter stimulus (Roberts, Fillmore, & Milich, 2011; Ross, Harris, Olincy, & Radant, 2000). Using this task, our group has examined the effects of moderate doses of alcohol on inhibitory control of attention in healthy social drinkers (Abroms, Gottlob, & Fillmore, 2006; Weafer & Fillmore, 2012b). These studies show that alcohol impairs inhibitory control of attention as evident by increased frequency with which participants attended to the distracter stimulus.

Although our prior research provides evidence that alcohol impairs inhibitory mechanisms of attention, it is not clear whether this impairing effect on attentional inhibition acts as a risk factor for harmful drinking. In the context of alcohol use, drinkers may exercise inhibitory control of attention to resist looking at alcohol-related cues when they intend to stop drinking. Several cognitive models of alcohol use suggest that the initiation of a drinking episode should be preceded by a shift in attention towards alcohol-related cues in the environment (Field, Wiers, Christiansen, Fillmore, & Verster, 2010; Franken, 2003). If the drinker is able to inhibit these attentional shifts towards alcohol-related cues, then they may be able to more effectively limit their drinking by ignoring cues signaling the availability of alcohol.

Inhibitory control of attention may be an important contributing factor to binge drinking, particularly in individuals who have an attentional bias towards alcohol-related stimuli in the drinking situation. Incentive theories of drug addiction propose that substance-related cues attract the attention of frequent users because they become associated with the pleasurable effects of the drug. Subsequent studies have confirmed that alcohol cues are more likely to capture the attention of heavy drinkers than moderate social drinkers (Field & Cox, 2008; Field, Mogg, & Bradley, 2004), presumably as a consequence of increased incentive salience of these cues for the heavy users (Robinson & Berridge, 1993). No research to date has examined whether inhibitory mechanisms of attention might protect against this attentional bias by allowing drinkers to better control their attention in a drinking context. For drinkers who show a strong attentional bias, the ability to inhibit shifts in attention towards alcohol related cues may be an important protective factor against harmful drinking.

The current study tested this notion by examining whether sensitivity to the disruptive effects of alcohol on the inhibitory control of attention was associated with alcohol use. Further, we examined whether this relation was moderated by participants’ level of attentional bias. We reasoned that among drinkers who show heightened attentional bias, those whose inhibitory control of attention is more impaired by alcohol would be more likely to drink heavily. Conversely, the impairing effect of alcohol on inhibitory control of attention might be less important for drinkers who show less attentional bias towards alcohol-related cues. We also tested for sex differences in task performance, because prior research has found that women show greater attentional disinhibition than men, both sober and under alcohol, which may act as a risk factor for heavy drinking among women (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012).

Two main hypotheses were proposed. First, we hypothesized that alcohol would impair participants’ ability to inhibit reflexive shifts of attention. Second we hypothesized that greater disinhibiting effects of alcohol would be associated with heavy alcohol use among drinkers with high attentional bias but not among those with little or no attentional bias.

Method

Participants

Participants were 80 adult social drinkers. Volunteers were recruited through advertisements (i.e., newspaper ads, posters, and online postings) seeking adult social drinkers for a study on the effects of alcohol on computer tasks. Participation was limited to individuals who were between the ages of 21 and 35 and had no uncorrected vision problems. Individuals who reported past or current severe psychiatric disorders (i.e., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) were not invited to participate. Those who reported infrequent drinking (i.e., less than one drinking occasion per month) or were found to be high risk for alcohol use disorder were not invited to participate. High-risk status was determined by a score of 5 or higher on the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Selzer, Vinokur, & Van Rooijen, 1975). Volunteers who reported other high-risk indicators of alcohol use disorder (e.g., prior treatment for alcohol use disorder, prior driving under the influence conviction) were not invited to participate. Demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Group Comparisons on Demographic Characteristics and Drinking Habits

| Male (n = 33) | Female (n = 47) | t | d | Total (n = 80) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | |||

| Demographic | ||||||||||

| Age | 22.6 | 2.0 | 21.0–28.0 | 23.7 | 2.6 | 21.0–32.0 | 2.1* | 0.48 | 23.3 | 2.4 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.0 | 13.2 | 53.2–94.2 | 71.7 | 11.1 | 51.0–93.2 | 0.5 | 0.11 | 72.2 | 11.6 |

| TLFB | ||||||||||

| Total Days | 30.8 | 16.4 | 4.0–88.0 | 28.4 | 12.6 | 6.0–58.0 | 0.7 | 0.17 | 29.4 | 14.2 |

| Total Drinks | 202.3 | 171.2 | 19.0–596.0 | 170.7 | 114.1 | 15.0–581.0 | 0.9 | 0.22 | 183.8 | 140.3 |

| Binge Days | 16.1 | 13.1 | 0.0–41.0 | 15.9 | 11.0 | 0.0–55.0 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 16.0 | 12.5 |

Note. TLFB refers to the timeline follow-back. TLFB assessed self-reported alcohol use over the past 90 days. t tests compared males and females on demographic and drinking variables.

p < .05

We have previously published manuscripts based on data (i.e., DORT performance) from a subset of these participants (n = 40) (Weafer and Fillmore, 2012b; 2013). The first of these manuscripts (Weafer and Fillmore, 2012b) examined the acute disinhibiting effects of alcohol on inhibitory control and tested dose-response curve using the DORT. The second study (Weafer and Fillmore, 2013) tested the acute effects of alcohol on attentional bias as measured by ocular fixation duration on a visual-probe task. The current study differs from these two studies because it examines how individual differences in magnitude of the disinhibiting effects of alcohol on the DORT relate to drinking habits. Further, it examines how this relation differs as a function of participants’ sober-state attentional bias as measured by visual-probe response time on the visual-probe task.

Materials

Delayed Ocular Response Task (DORT)

The DORT assesses inhibitory control of attention by measuring a participant’s ability to inhibit a reflexive saccade toward the sudden appearance of a goal-irrelevant distracter stimulus on a computer screen. Eye movement was recorded using a Model 504 Eye Tracking System (Applied Science Laboratory, Boston, MA, USA), and we have described the technical specifications of this apparatus in a prior manuscript (Roberts et al., 2011). Participants were seated in a darkened room and instructed to maintain focus on a fixation point. While participants were focused on the fixation point, a bright target stimulus was presented in the periphery, and participants were instructed to inhibit looking at this distracter and maintain their gaze on the fixation point until it disappeared. This task has been used in previous research to demonstrate the acute disinhibiting effects of alcohol (Abroms et al., 2006).

A trial began with the presentation of a white fixation point (+) with a luminance of 39.6 lux presented against a black background. Participants were instructed to fixate on this point. After 1,500 ms, the distracter stimulus (a white circle) briefly appeared for 100 ms to the left or right of the fixation point. The fixation point then remained on the screen for a random “wait” interval (800, 1,000, and 1,200 ms). Participants were told to withhold any saccade to the distracter. Following the wait interval, the central fixation point disappeared and the display was blank for 1,000 ms. Participants were told to execute a saccade to the location of the distracter as quickly as possible upon the disappearance of the fixation point.

The task consisted of 96 trials and required 7 minutes to complete. Fixation points and distracters were presented in five locations that were separated from each other by 4.1° of visual angle. These positions were distributed horizontally across the center of the screen, resulting in four possible visual angles between the fixation point and target (4.1°, 8.2°, 12.3°, and 16.4°). Each trial began with the presentation of the fixation point at the target location of the preceding trial. The three different wait intervals each occurred in 32 trials. Target locations and wait intervals were presented in a random and unpredictable sequence.

The main criterion variable on the DORT was the number of trials during which participants made premature saccades. Saccades were considered premature if they occurred after the distracter was presented but before fixation point disappeared. Two other measures of interest included saccadic RT and saccadic accuracy. Saccadic RT was defined as the time elapsed between the disappearance of the fixation point and the completion of a saccade towards the target region. Saccadic accuracy was defined as the angular discrepancy between the target position and the landing point of the saccade. The difference between these two locations was measured in terms of degree of absolute deviation; greater deviation scores indicated poorer accuracy of the saccades.

Visual-Probe Task

Attentional bias was measured using a visual-probe task and participants were tested in a sober state. This task required participants to view a neutral and an alcohol-related image presented side by side on a computer monitor. A visual-probe replaced either the left or right image as they were removed from the display. Participants were instructed to respond to the visual-probe by pressing one of two response keys on a keyboard according to the side on which the visual-probe appeared.

The pictures consisted of 10 alcohol-related images that were matched with 10 neutral (i.e., nonalcohol) images. The alcohol images depicted an alcohol beverage. These images were matched with neutral images consisting of nonalcoholic drinks (e.g., a bottle of soda matched with a bottle of beer). All images were photographed against a white background.

The 10 image pairs were presented four times, once for each of the four possible picture/target combinations (i.e., left and right picture locations and left and right visual-probe locations) for a total of 40 test trials. Additionally, there were 40 filler trials that consisted of 10 pairs of neutral images presented four times each. These filler trials were included to reduce the possible habituation to alcohol stimuli that might occur if all trials contained alcohol-related images. The 40 filler trials were intermixed with the 40 test trials, so the task included 80 trials in total.

Each trial was a set sequence of events. First, a fixation point (+) was presented at the center of the screen for 500 ms. Second, a pair of images was displayed for 1,000 ms. Third, a visual-probe (an “X”) appeared on the left or right side of the screen in the position where one of the pictures was previously displayed. Participants then pressed one of two keys (“>” or “/”) on a standard keyboard according to the location of the visual-probe. Responses that occurred less than 100 ms after the probe was presented were considered anticipatory and removed from later analysis, and those occurring more than 1,000 ms after the probe was presented were considered late and removed from later analysis. Attentional bias was defined as the difference in RT to probes replacing alcohol-related images relative to probes replacing neutral images, such that faster RT to probes replacing alcohol-related images was indicative of greater attentional bias. Prior research has shown that these measures of attentional bias are stable over time (Miller & Fillmore, 2011) and assess an enduring trait rather than a passing state (Broadbent & Broadbent, 1988).

Timeline Follow-back

Participants’ drinking habits were assessed using the Timeline Follow-back procedure (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992), which assessed daily drinking patterns over the past three months. Three measures of drinking habits were obtained: (a) total number of drink consumed (total drinks), (b) total number of drinking days (drinking days), and (c) total number of binge drinking days (binge days). Binge drinking was defined as consuming enough alcohol to yield a BAC greater than 80 mg/100 ml, which is consistent with NIAAA guidelines. To calculate BAC for each day, participants estimated the number of standard drinks they consumed and the number of hours they spent drinking. This information, along with participants’ sex and body weight, was used to estimate the resultant BAC obtained for each drinking day using well-established anthropometric-based BAC estimation formulae based on body weight and gender and that assumed an average clearance rate of 15 mg/dl per hour (Watson, Watson, & Batt, 1981). Because of the high intercorrelations between TLFB variables, we z-transformed and averaged total drinks, drinking days, and binge days to produce a composite drinking habits variable that was used in subsequent analyses (α = .90).

Procedure

Eligible participants attended a familiarization session and two dose-challenge sessions. Sessions were separated by at least 24 hours and participants completed all sessions within 4 weeks. Participants were required to fast for 4 hours prior to each dose-challenge session. They were instructed to abstain from consuming alcohol or using other psychoactive drugs 24 hours before each session. Prior to each dose-challenge session, participants provided urine samples that were tested for the presence of drug metabolites (ON trak TesTstiks, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), and those who tested positive for the presence of illicit drugs did not complete the session. Female participants were also tested for hCG in order to verify that they were not pregnant (Mainline Confirms HGL, Mainline Technology, Ann Arbor, MI). Breath samples were taken at the beginning of each session to verify zero BAC (Intoxilyzer, Model 400; CMI, Owensboro, KY).

Familiarization session

Participants were screened to ensure that they met criteria for the study during a familiarization session. Those who did not meet criteria were paid $10 and discontinued. Those who met criteria completed behavioral tasks and a practice version of the DORT, filled out questionnaires, and provided informed consent for participation.

Alcohol-administration sessions

Participants completed dose challenge sessions under 0.64 g/kg alcohol and 0.0 g/kg alcohol (placebo). Following the 0.64 g/kg dose, a peak BAC of 80 mg/ 100 ml was expected to occur approximately 75 minutes after drinking began. This peak BAC estimate was based on prior work in our lab using similar alcohol doses (Fillmore & Blackburn, 2002). Dose order was counterbalanced across participants, and doses were calculated based on body weight. The 0.64 g/kg dose was served as one part alcohol and three parts carbonated mix divided equally into two glasses. The placebo beverage consisted of four parts carbonated mix that matched the volume of the 0.64 g/kg alcohol dose. Five ml of alcohol was floated on top of each placebo glass, and the glasses were sprayed with an alcoholic mist that resembled condensation and provided a strong alcohol odor. Previous research has shown that individuals report that these beverages contain alcohol (Fillmore & Blackburn, 2002). Participants consumed both servings in a six minute period with a brief interval between servings as the experimenter prepared the second beverage.

Participants provided expired air samples approximately 40 and 60 minutes after drinking and started the DORT between 40 and 50 minutes after drinking. After testing, participants remained at leisure in a lounge area until their BAC fell to 20 mg/100 ml or below, at which time they were allowed to leave. They were provided with transportation home as needed.

Data Analysis

The criterion measures of interest from the dose-challenge sessions included number of premature saccades, saccadic RT, and saccadic accuracy on the DORT. Alcohol effects on attentional control were analyzed using mixed model General Linear Models (GLM) with dose as a categorical within-subject factor (placebo versus 0.64 g/kg), sex as a categorical between-subjects factor (male versus female), and attentional bias score as a continuous between-subjects factor. Significant interactions were probed using a priori t tests. We tested whether BACs were associated with any individual difference variables (i.e., sex, attention bias) using mixed-model GLM with time as a categorical within-subject factor (40 min versus 60 min after drinking), sex as a categorical between-subjects factor (male versus female), and attentional bias as a continuous between subjects factor. We also examined whether BACs were associated with premature saccades on the DORT under 0.64 g/kg alcohol using correlation analyses.

The hypothesis that magnitude of alcohol impairment on the DORT would show a stronger association with drinking behavior among drinkers with higher attentional bias was tested using regression analyses. To reduce unnecessary multicollinearity, we z-transformed all variables that were included in the regression models. We used hierarchical regression models to test whether attentional bias moderated the relation between alcohol impairment on the DORT and drinking habits. Specifically, the composite drinking variable from the TLFB was regressed onto degree of alcohol impairment (step 1), attentional bias score (step 2), and an alcohol impairment × attentional bias interaction term (step 3) in a hierarchical regression model. Degree of alcohol impairment was calculated by subtracting the number of premature saccades participants made under placebo from their number of premature saccades made under 0.64 g/kg alcohol.

Results

Demographics and Attentional Bias

Participants’ self-reported drinking habits and demographic information are reported separately by sex in Table 1. Participants responded more quickly to visual-probes replacing alcohol pictures (M = 396.9, SD = 45.1) than to probes replacing neutral pictures (M = 402.3, SD = 50.2), and this difference was significant, t (79) = 2.0, p = .049, d = 0.22. There was no significant sex difference in participants’ levels of attentional bias, t (78) = 0.2, p = .874, d = 0.05.

Blood Alcohol Concentrations

Participants’ mean (SD) BACs were 74.6 mg/100 ml (18.9 ml/100 ml) approximately 40 minutes following the dose and 79.1 mg/100 ml (16.8 mg/ 100 ml) approximately 60 minutes following the dose. There was no significant main effect of sex, F (1, 77) = 0.5, p = .464, η2 = .01, or attentional bias, F (1, 77) = 0.1, p = .762, η2 < .01. There was a significant main effect of time, F (1, 77) = 7.6, p = .007, η2 = .09, owing to the gradual rise in BAC during the ascending limb of the BAC curve. There was no significant interaction involving sex or attentional bias, ps ≥ .402. BACs were not significantly correlated with premature saccades on the DORT under 0.64 g/kg alcohol, ps ≥ .119. No detectable BAC was observed in the placebo condition.

Acute Effects of Alcohol

Premature Saccades

Performance on the DORT under placebo and 0.64 g/kg alcohol is reported in Table 2. There was a significant main effect of dose, F (1, 77) = 17.2, p < .001, η2 = .18, confirming that the number of premature saccades was greater following 0.64 g/kg alcohol compared with placebo. Neither the main effect of sex, F (1, 77) = 2.4, p = .122, η2 = .03, nor the main effect of attentional bias, F (1, 77) = 0.1, p = .720, η2 < .01, was significant. The dose X sex interaction was not significant, F (1, 77) = 0.3, p = .573, η2 < .01, nor was any other interaction effect, ps ≥ .334. These nonsignificant interactions suggest that that the effects of alcohol on premature saccades were similar across sexes and levels of attentional bias.

Table 2.

Alcohol Effects on DORT Performance

| Dose | ||

|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 0.64 g/kg | |

| DORT | ||

| Premature Saccades | 6.0 (6.3) | 9.6 (9.2) |

| Accuracy | 3.9 (0.6) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| RT | 352.6 (71.6) | 387.5 (76.6) |

Note. Accuracy is mean degree deviation from remembered location of the distracter stimulus. RT is the time elapsed between the removal of the fixation point and the completion of the saccade towards the previous distracter location.

Saccadic RT

There was a significant main effect of dose, F (1, 77) = 6.2, p = .015, η2 = .07, confirming that saccadic RT was slower under 0.64 g/kg alcohol than under placebo. Neither the main effect of sex, F (1, 77) = 0.1, p = .731, η2 = .02, nor the main effect of attentional bias, F (1, 77) = 0.1, p = .715, η2 < .01, was significant. The dose × sex interaction was not significant, F (1, 77) = 3.6, p = .063, η2 = .04, nor was any other interaction effect, ps ≥ .649.

Saccadic Accuracy

There was a significant main effect of dose, F (1, 77) = 15.7, p < .001, η2 = .17, confirming that participants were more accurate following placebo than 0.64 g/kg alcohol. Neither the main effect of sex, F (1, 77) = 2.1, p = .148, η2 = .03, nor the main effect of attentional bias, F (1, 77) = 2.7, p = .106, η2 = .03, was significant. The dose × sex interaction was not significant, F (1, 77) < 0.1, p = .953, η2 < .01, nor was any other interaction effect, ps ≥ .667.

Relation of Alcohol Induced Disinhibition of Attention and Drinking Habits

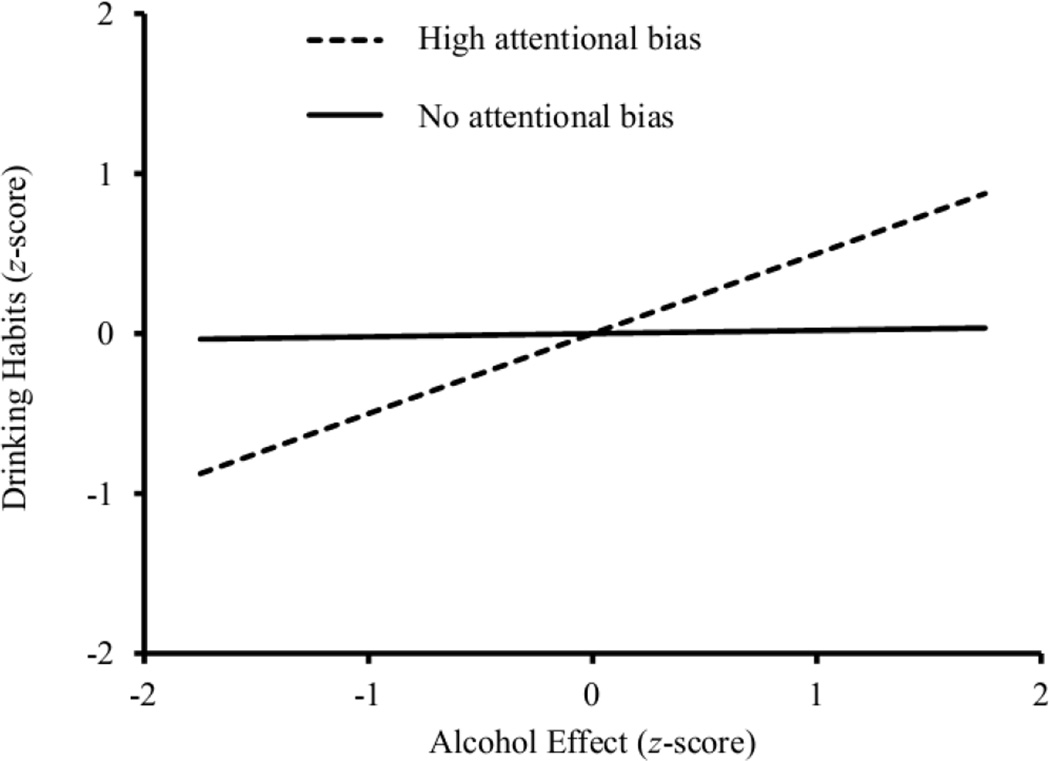

Hierarchical regression models are presented in Table 3. These models show that there was a marginally significant relation between alcohol impairment on the DORT and the composite drinking habits variable. Moreover, the addition of an attentional bias × alcohol sensitivity interaction term resulted in a significant increase in R2. This significant interaction confirms that the relation between the magnitude of alcohol effect and drinking habits differs according to participants’ level of attentional bias. To interpret this significant interaction, the alcohol sensitivity term was plotted against the drinking habits variable at the level of no attentional bias (i.e., no difference in visual-probe reaction time to probes replacing neutral and alcohol images) and high attentional bias (i.e., 1.5 SD above the mean), and the significance of these simple slopes were tested (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). These analyses directly tested the hypothesis that degree of alcohol impairment is associated with drinking habits among drinkers with high attentional bias but not among drinkers without any attentional bias. Simple slopes at these two different levels of attentional bias are presented in Table 3 and graphed in Figure 1. Among the drinkers with high attentional bias, participants who showed the largest magnitude of alcohol impairment also reported the heaviest drinking. In fact, at this high level of attentional bias, magnitude of alcohol impairment accounted for 25% of the variance in drinking habits. For drinkers with no attentional bias, however, magnitude of alcohol impairment was not associated with drinking habits.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regressions of Attentional Bias and Alcohol Effects on DORT Performance on Composite Drinking Habits Variable

| Independent Variable | Hierarchical Models | Simple Slopes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AB | High AB | |||||||

| B | ΔF | ΔR2 | t | B | t | B | ||

| Step 1 | Alcohol Effect | 0.18 | 3.1 | .04 | ||||

| Step 2 | Attentional Bias | 0.05 | 0.3 | .00 | ||||

| Step 3 | Attentional Bias × Alcohol Effect | 0.28 | 7.3** | .08 | 0.2 | 0.02 | 2.7** | 0.50 |

Note. Alcohol effect is the magnitude of the alcohol effect on premature saccades (i.e., premature saccades under 0.64 g/kg alcohol minus premature saccades under placebo). No AB describes the simple slope when participants showed no difference in RT to probes replacing neutral and alcohol images. High AB describes the simple slope 1.5 standard deviations above the mean value of attentional bias.

p < .05,

p < .01

Figure 1.

Differential relations between the magnitude of alcohol impairment and drinking habits on the TLFB at two levels of attentional bias. High attentional bias describes the simple slope 1.5 standard deviations above the mean value of attentional bias. No attentional bias describes the simple slope when participants showed no difference in RT to probes replacing neutral and alcohol images.

As seen in Table 1, there was significant variability in drinking habits, and there was a positive skew on the TLFB variables. This positive skew occurred because there was a cluster of heavy drinkers on the positive tail of the distribution. We conducted log transformations on the composite drinking habits variable from the TLFB to normalize its distributions, which corrected for its positive skew. We then reran the hierarchical regression analyses with these transformed drinking measures as dependent variables and there were no changes in the significance of the results.

Specificity of the Relation between Alcohol Impairment of Attention and Drinking Habits

A series of supplemental analyses were conducted to establish the specificity of the relation between alcohol impairment of attentional inhibition and drinking habits. First, it is possible that heavier alcohol use could be related to poor attentional inhibition in general and not necessarily the degree to which attentional inhibition was impaired by alcohol. To rule out this possibility, we reran the regression analyses described above using premature saccades under placebo rather than impairment scores to test whether sober-state performance on the DORT was associated with drinking habits. These analyses showed that premature saccades on the DORT following placebo was not associated with drinking habits, nor did it interact with participants’ level of attentional bias to predict drinking habits (ps > .05).

Second, it is possible that heavier drinkers were simply more impaired by alcohol regardless of the aspect of attention being measured. To test this possibility, we reran the hierarchical regression analysis reported in Table 3 using magnitude of impairment for the other DORT variables (i.e., saccadic RT, saccadic accuracy) as the predictor variable along with the measure of attentional bias. There was no significant main effect or interaction for either of these measures of alcohol impairment, (p > .05). Therefore, it was specifically alcohol impairment of the ability to inhibit shifts in attention that was associated with drinking behavior among participants with high attentional bias.

Discussion

The current study examined the relation between the degree of alcohol-impairment of attentional inhibition and drinking habits in drinkers who showed attentional bias towards alcohol-related cues compared with those with no such attentional bias. On the laboratory measure of attentional control, alcohol increased inhibitory failures, slowed saccadic RT, and reduced saccadic accuracy. This pattern of impairment is consistent with those previously reported by our group (Abroms et al., 2006). Consistent with our hypotheses, sensitivity to the impairing effect of alcohol on inhibitory control of attention was associated with self-reported drinking habits, and the magnitude of the relation between alcohol impairment of attentional inhibition and drinking habits differed according to participants’ level of attentional bias. Among drinkers with higher attentional bias, magnitude of alcohol impairment was associated with drinking habits. Among drinkers with little or no attentional bias, however, sensitivity to alcohol was not associated with any measure of drinking habits. Interestingly, magnitude of alcohol impairment of saccadic reaction time and saccadic accuracy was not associated with drinking habits. The specificity of this relation is noteworthy because it suggests that sensitivity to alcohol’s disinhibiting effect of attentional control, and not general sensitivity to alcohol-impairment, may contribute to excessive alcohol use. We were unable to replicate previous findings in our laboratory showing that women make more attentional inhibitory failures than do men, both sober and under alcohol (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012b).

These findings may help explain how an attentional bias to alcohol cues, coupled with impaired inhibitory control of attention, can interact to contribute to alcohol use. Contemporary models of addiction suggest that neurocognitive factors leading to dysregulated substance use are impaired executive functions (e.g., poor inhibitory control) and exaggerated salience attribution towards substance-related cues (Field et al., 2010; Goldstein & Volkow, 2002). Substance users show heightened drug seeking behaviors (e.g., attentional bias) due to this reward attribution and have difficulty controlling these behaviors due to deficits of executive control. Several authors have speculated on a synergistic effect of heightened incentive salience of drug-related cues and an inability to inhibit impulsive behavior that could lead to excessive consumption (Dawe, Gullo, & Loxton, 2004; Field & Cox, 2008). The results of the current study are consistent with such dual-process models because sensitivity to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol positively correlated with alcohol use only among drinkers whose attention was biased towards alcohol-related cues. As such, studies that examine these risk factors in isolation may underestimate the degree to which disruption of inhibitory control and heightened approach behaviors confer risk in substance users.

A novel contribution of this research is that we demonstrated a relation between the integrity of attentional inhibition and alcohol use. Many theoretical models of behavioral control identify the ability to redirect attention as an integral part of initiating (or inhibiting) an action (Franken, 2003; Lang, 1995). For example, Hanif et al. (2012) showed that manipulating people’s attention in ways that decreased focus on goal-irrelevant distracter information and increased the salience of goal-related information led to improved self-regulation. Despite this clear link between attention and self control, the relation between attentional inhibition and externalizing behaviors (e.g., alcohol use, impulsivity) is understudied. Much of the research examining how inhibitory control relates to substance use is conducted using tasks such as the go/no-go task that measure participants’ ability to inhibit a manual response (Weafer et al., 2008). Indeed, the ability to inhibit a behavioral response (i.e., stopping oneself from taking another drink) is critically important for controlling behavior—a drinker who intends to discontinue a drinking episode must use inhibitory control to terminate an ongoing behavioral response. However, these laboratory models of manual response inhibition do not consider the importance of shifting the focus of attention when switching or inhibiting an ongoing response. If a manual response is inhibited without a corresponding shift in attention away from the to-be-ignored stimulus, then the individual will remain focused on the stimulus and eventually reengage with it. In the context of alcohol use, inhibiting attentional shifts towards alcohol-related cues may be a prerequisite condition for ending a drinking episode, because drinkers who remain focused on alcohol cues have more opportunity to capitulate to their impulses and reinitiate drinking (Franken, 2003). Future studies examining how drinkers exercise inhibitory control over manual and attentional responses to regulate their drinking will be necessary to better understand how these cognitive processes interact with one another in the context of alcohol use.

Given that attentional bias may represent a risk factor for heavy drinking especially in those individuals who show compromised attentional inhibition, it may be important to examine attentional bias in clinical groups characterized by impaired attention (e.g., people with schizophrenia or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]; Ross et al., 2000). Supporting this notion, our group has shown that unlike nonclinical adults, adults with ADHD show an increase in attentional bias towards alcohol cues after drinking, and this increased attentional bias is associated with higher levels of alcohol use (Roberts et al., 2012). Further, among adults with ADHD, impairment of attentional inhibition is associated with heightened rates of alcohol use (Weafer, Milich, & Fillmore, 2011). Based on these findings and those of the current study, this combination of impaired attentional inhibition and heightened attentional bias after drinking may help explain why clinical groups with impairments of attention, such as adults with ADHD, are at increased risk for harmful alcohol use (Derefinko & Pelham, in press; Regier et al., 1990).

In the current study we conceptualized impairment of inhibitory control and heightened attentional bias as separate but interactive risk factors for heightened alcohol use. Another possibility for understanding the interplay between these two risk factors is to directly assess participants’ ability to inhibit behavioral and attentional responses to alcohol-related stimuli. Such a methodology could be used to directly examine how alcohol-related cues affect drinkers’ inhibitory control. Several studies have attempted to develop such tasks. Our group (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012a) recently showed that alcohol-related cues reduced social drinkers’ ability to inhibit a manual response on a modified go/no-go task. Considering the finding of the current study, a future direction for this line of research may be to develop a task where participants are required to inhibit their gaze towards an alcohol-related visual cue (but see Jones & Field, 2013).

This research contributes to our understanding of the relation among inhibitory control, attentional bias, and alcohol use; however, it is important to consider limitations to the design. First, we used the DORT to measure attentional inhibition, and performance on the DORT may be influenced by other cognitive functions (e.g., working memory; Hutton, 2008). Using additional measures of attentional inhibition (e.g., antisaccade task) in future studies will increase confidence in our findings. Second, we examined the relation between DORT performance under placebo and drinking habits to determine whether baseline attentional inhibition was related to drinking habits. Ideally, we would have measured attentional inhibition during a no beverage control session, because the expectation of receiving alcohol can influence behavior (Fillmore & Blackburn, 2002).

Finally, our assessment of alcohol use was based on participants’ retrospective self-report. Other studies have used ad libitum consumption tasks that assess alcohol use in a standardized laboratory setting (Roberts, Fillmore, & Milich, 2012; Weafer & Fillmore, 2008). However, a benefit of the TLFB provides detailed information about patterns of recent alcohol use outside of the laboratory (e.g., patterns of binge use), which increases confidence in the external validity of our findings. Further, the validity of the TLFB as a measure of drinking habits is well established (Sobell & Sobell, 1992). Nonetheless, future studies should include a measure of ad libitum consumption to increase confidence in these findings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants R01 AA012895, R01 AA018274, F31 AA018584, and F31 AA021028, and National Institute on Drug Abuse grant T32 DA007304. These funding sources had no role in the research other than financial support.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Abroms BD, Gottlob LR, Fillmore MT. Alcohol effects on inhibitory control of attention: Distinguishing between intentional and automatic mechanisms. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:324–334. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0524-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent D, Broadbent M. Anxiety and attentional bias: State and trait. Cognition & Emotion. 1988;2:165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Carr LA, Nigg JT, Henderson JM. Attentional versus motor inhibition in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology. 2006;20:430–441. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.4.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Gullo MJ, Loxton NJ. Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: Implications for substance misuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1389–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Crean J, Richards JB. Effects of d-amphetamine and ethanol on a measure of behavioral inhibition in humans. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:830–837. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.4.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derefinko KJ, Pelham WE. ADHD and substance use. In: Sher K, editor. Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Dependence. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Cox WM. Attentional bias in addictive behaviors: A review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Mogg K, Bradley BP. Eye movements to smoking-related cues: Effects of nicotine deprivation. Psychopharmacology. 2004;173:116–123. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Wiers RW, Christiansen P, Fillmore MT, Verster JC. Acute alcohol effects on inhibitory control and implicit cognition: Implications for loss of control over drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1346–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT. Drug abuse as a problem of impaired control: Current approaches and findings. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2003;2:179–197. doi: 10.1177/1534582303257007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Blackburn J. Compensating for alcohol-induced impairment: Alcohol expectancies and behavioral disinhibition. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:237–246. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. Application of a behavioral theory of motivation to the concepts of anxiety and impulsivity. Journal of Research in Personality. 1987;21:417–435. [Google Scholar]

- Franken IHA. Drug craving and addiction: Integrating psychological and neuropsychopharmacological approaches. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2003;27:563–579. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: Neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanif A, Ferry AE, Frischen A, Pozzobon K, Eastwood JD, Smilek D, Fenske MJ. Manipulations of attention enhance self-regulation. Acta Psychologica. 2012;139:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton SB. Cognitive control of saccadic eye movements. Brain and Cognition. 2008;68:327–340. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: Implications for the control of behavior by reward-related stimuli. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:373–390. doi: 10.1007/pl00005483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Field M. The effects of cue-specific inhibition training on alcohol consumption in heavy social drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21:8–16. doi: 10.1037/a0030683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ. The emotion probe: Studies on motivation and attention. American Psychologist. 1995;50:372–385. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.5.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Cowan WB, Davis KA. On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction-time responses: A model and a method. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1984;10:276–291. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyvers M. "Loss of control" in alcoholism and drug addiction: A neuroscientific interpretation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:225–249. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Fillmore MT. Persistence of attentional bias toward alcohol-related stimuli in intoxicated social drinkers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;117:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill LE, Skilling TA, Vogel-Sprott M. Alcohol and the ability to inhibit behavior in men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:600–605. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson MS, Kramer AF, Irwin DE. Covert shifts of attention precede involuntary eye movements. Perception & Psychophysics. 2004;66:398–405. doi: 10.3758/bf03194888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1990;13:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos CX, Parker JL, Le DA. Increased impulsivity after injected alcohol predicts later alcohol consumption in rats: Evidence for "loss-of-control drinking" and marked individual differences. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1998;112:1247–1257. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Compulational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W, Fillmore MT, Milich R. Separating automatic and intentional inhibitory mechanisms of attention in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:223–233. doi: 10.1037/a0021408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W, Fillmore MT, Milich R. Drinking to distraction: Does alcohol increase attentional bias in adults with ADHD? Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20:107–117. doi: 10.1037/a0026379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RG, Harris JG, Olincy A, Radant A. Eye movement task measures inhibition and spatial working memory in adults with schizophrenia, ADHD, and a normal comparison group. Psychiatry Research. 2000;95:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, Van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tipper SP. The negative priming effect: Inhibitory priming by ignored objects. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1985;37A:571–590. doi: 10.1080/14640748508400920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PE, Watson ID, Batt RD. Prediction of blood alcohol concentrations in human subjects. Updating the Widmark Equation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1981;42:547–556. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Individual differences in acute alcohol impairment of inhibitory control predict ad libitum alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology. 2008;201:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Alcohol-related stimuli reduce inhibitory control of behavior in drinkers. Psychopharmacology. 2012a;222:489–498. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2667-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Comparison of alcohol impairment of behavioral and attentional inhibition. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012b;126:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Acute alcohol effects on attentional bias in heavy and moderate drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:23–41. doi: 10.1037/a0028991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Milich R, Fillmore MT. Behavioral components of impulsivity predict alcohol consumption in adults with ADHD and healthy controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]