Abstract

Background

Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) is the most abundant CYP enzyme in the liver, which metabolizes approximately 50% of the marketed drugs including antiretroviral agents. CYP3A4 induction by ethanol and its impact on drug metabolism and toxicity is known. However, CYP3A4–ethanol physical interaction and its impact on drug binding, inhibition, or metabolism is not known, except that we have recently shown that ethanol facilitates the binding of a protease inhibitor (PI), nelfinavir, with CYP3A4. The current study was designed to examine the effect of ethanol on spectral binding and inhibition of CYP3A4 with all currently used PIs that differ in physicochemical properties.

Methods

We performed type I and type II spectral binding with CYP3A4 at 0 and 20 mM ethanol and varying PIs’ concentrations. We also performed CYP3A4 inhibition using 7-benzyloxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin substrate and NADPH at varying concentrations of PIs and ethanol.

Results

Atazanavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir showed type I spectral binding, whereas indinavir and ritonavir showed type II. However, amprenavir and darunavir did not show spectral binding with CYP3A4. Ethanol at 20 mM decreased the maximum spectral change (δAmax) with type I lopinavir and saquinavir, but it did not alter δAmax with other PIs. Ethanol did not alter spectral binding affinity (KD) and inhibition constant (IC50) of type I PIs. However, ethanol significantly decreased the IC50 of type II PIs, indinavir and ritonavir, and markedly increased the IC50 of amprenavir and darunavir.

Conclusions

Overall, our results suggest that ethanol differentially alters the binding and inhibition of CYP3A4 with the PIs that have different physicochemical properties. This study has clinical relevance because alcohol has been shown to alter the response to antiretroviral drugs, including PIs, in HIV-1-infected individuals.

Keywords: CYP3A4, Alcohol, Protease Inhibitors, Spectral Binding, Inhibition

CYTOCHROME P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) is the most abundant CYP enzyme in the liver, which is responsible to metabolize approximately 50% of the marketed drugs including antiretroviral agents non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) and protease inhibitors (PIs) (Anzenbacher and Anzenbacherová, 2002). In addition to substrates, several NNRTIs and PIs act as CYP3A4 inducers, inhibitors, or both (Acosta, 2002; Eagling et al., 1997; Granfors et al., 2006; Walubo, 2007; Xu and Desai, 2009). As highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens consist of multiple drugs, especially NNRTIs and PIs, there are several reports of drug–drug interactions as a result of CYP3A4 induction or inhibition (Pal and Mitra, 2006; Walubo, 2007), for example, ritonavir is present in most of the HAART regimens, because it is an extremely potent inhibitor of CYP3A4. Thus, ritonavir leads to increased bioavailability of NNRTIs and PIs because of their decreased metabolism by CYP3A4 (Acosta, 2002; Xu and Desai, 2009).

Saquinavir is the first PI that was used for the treatment of HIV-1 infection approximately 25 years ago (Roberts et al., 1992). Subsequently, several other PIs: ritonavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, amprenavir, fosamprenavir, atazanavir, tipranavir, lopinavir, and darunavir were developed and prescribed over the past 2 decades (De Clercq, 2009a,b). In the past 15 years, there has been a clear trend of reduced prescription of indinavir, nelfinavir, and saquinavir, mainly because of the toxicities of the drugs or drug metabolites, as well as drug–drug interactions (Jiménez-Nácher et al., 2008). On the other hand, the prescription of atazanavir, fosamprenavir, darunavir, lopinavir, and tipranavir has increased since their first use. Fosamprenavir is a prodrug, which is eventually converted into active drug amprenavir. In the past couple of years, fosamprenavir/ritonavir (Arvieux and Tribut, 2005), atazanavir/ritonavir (Croom et al., 2009), darunavir/ritonavir (McKeage et al., 2009; Rittweger and Arastéh, 2007), and lopinavir/ritonavir (Croxtall and Perry, 2010) are gaining significant attention because of the reduced risk of adverse reactions and their ability to cross blood–brain barrier.

Ethanol is known to interact with many medications, including PIs, through CYP3A4 induction leading to altered drug metabolism and toxicity in the liver (Flexner et al., 2002; Fraser, 1997; Weathermon and Crabb, 1999). Recently, we have shown that ethanol also induces CYP3A4 in monocyte-derived macrophage (Jin et al., 2011), which is one of the HIV-1 replication sites and therefore target of PIs (Gavegnano and Schinazi, 2009). Thus, individuals who consume ethanol and take PI drugs are at high risk of deleterious ethanol–PIs interaction. Although CYP3A4 induction by alcohol is well documented (Flexner et al., 2002; Fraser, 1997; Weathermon and Crabb, 1999), there is no report on ethanol–CYP3A4 physical interaction and its impact on PIs–CYP3A4 interaction. Recently, based on spectral binding and inhibition studies, we have shown that ethanol binds to the active site of CYP3A4 and facilitates the binding of nelfinavir with CYP3A4 (Kumar et al., 2010). As PIs have different physicochemical properties, such as size, shape, polarity, and hydrophobicity, it is logical to anticipate that alcohol will show differential CYP3A4–PIs interactions. This hypothesis was tested by studying spectral binding and inhibition of CYP3A4 with different PIs (amprenavir, atazanavir, darunavir, indinavir, lopinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir) currently available for clinical use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

7-benzyloxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (7-BFC) and 7-hydroxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (7-HFC) were purchased from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR). All the PIs were bought from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON, Canada). NADPH was from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Ethanol was obtained from Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA). Ni-NTA affinity resin was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). CYP3A4, cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR), and cytochrome b5 (b5) containing plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. James Halpert (Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California San Diego). All other chemicals were of the highest grade available and were obtained from standard commercial sources.

Enzyme Preparation

CYP3A4 enzyme was expressed as His-tagged proteins in E. coli TOPP3 and purified using an Ni-affinity column, as described previously (Domanski et al., 2001; Harlow and Halpert, 1998). Recombinant CPR and b5 from rat liver were prepared as described previously (Harlow and Halpert, 1998) at Protein Production Core Laboratory, KU Higuchi Bioscience Center, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein assay kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The specific content of CYP3A4 was 12 nmol of P450 per mg protein.

Spectral Binding

For binding studies, difference spectra were recorded on a 6800 UV/VIS JENWAY double beam spectrophotometer (Bibby Scientific Limited, Staffordshire, UK) at 25°C, as described earlier (Kumar et al., 2010; Talakad et al., 2009). Briefly, buffer (Hepes 0.1 M, pH 7.4) containing 0.5 µM CYP3A4 was preincubated in sample and reference cuvettes in the spectrophotometer for 3 minutes. The same amount of methanol was added to the reference cuvette, as all the PIs were dissolved in methanol. The final methanol concentrations were kept at 1%. The difference in absorbance between the maxima and minima (δA) was recorded 2 minutes after the addition of the PIs to the sample cuvette. PIs upon binding to CYP3A4 can exhibit type I spectral change, which is characterized by an increase in absorbance at a wavelength between 385 and 390 nm (high spin state of the heme iron) and a decrease in absorbance at a wavelength between 416 and 420 nm (low spin state of the heme iron). Similarly, PIs upon binding to CYP3A4 can exhibit type II spectral change, which is usually characterized by an increase in absorbance at a wavelength between 424 and 432 nm and a decrease in absorbance at a wavelength between 412 and 406 nm. The type I and type II spectral changes occur by noncovalent and covalent binding of PIs to the heme, respectively, resulting into removal of sixth ligand (water molecule) of the heme.

To examine the effect of ethanol on spectral binding, CYP3A4 was preincubated with 20 mM ethanol in both the cuvettes prior to titration with the PIs. This concentration was chosen based on our earlier titration experiment with ethanol (Kumar et al., 2010) and relevance to physiological concentration (approximately 0.1%) in binge and mild-to-moderate chronic alcoholics. The spectral dissociation constants (KD) were obtained by fitting the data (δA vs. PIs’ concentration) using nonlinear regression analysis to a single-site ligand binding equation using Sigma plot 11 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). To accurately determine the relative KD and δAmax values and minimize experimental errors, spectral binding with and without ethanol were performed successively using the same cocktail solution of ethanol and PIs.

CYP3A4 Inhibition

Inhibition of CYP3A4 by all the PIs was determined using 7-BFC debenzylation reaction essentially as described earlier (Kumar et al., 2006, 2010). In brief, 100 µl reaction mixture contained 75 µM 7-BFC (1% methanol) and varying concentrations of the PIs (0 to 50 µM) in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2. The standard reconstitution system contained 10 pmol CYP3A4, 40 pmol CPR, 20 pmol b5, and 10 µg dioleoyl-phosphatidylcholine. The reaction was performed at 37°C for 5 minutes using 1 mM NADPH. The activity in the absence and presence of inhibitors was determined by measuring 7-HFC at λex = 410 nm and λem = 535 nm. Nonlinear regression analysis was performed to fit the data to a hyperbolic decay equation to derive the IC50 values using Sigma plot 11. To examine the effect of ethanol on CYP3A4 inhibition, CYP3A4 and 7-BFC/PI cocktails were independently preincubated with 20 mMethanol prior to the addition of NADPH to initiate the reaction. To accurately determine the relative IC50 values and minimize experimental errors, inhibition with and without ethanol were performed simultaneously using the same cocktail solutions of ethanol, 7-BFC, and PIs.

RESULTS

Effect of Ethanol on Spectral Binding of PIs with CYP3A4

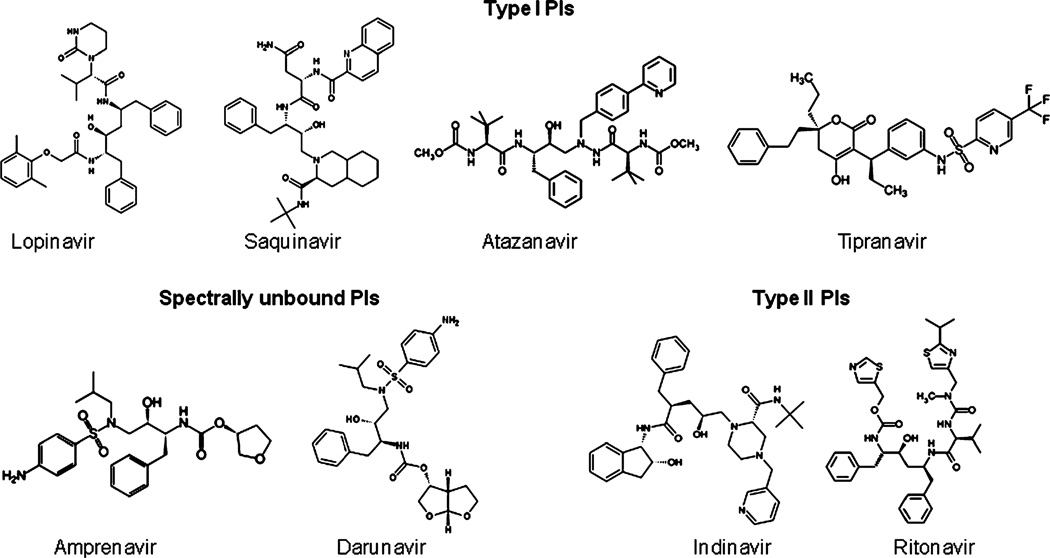

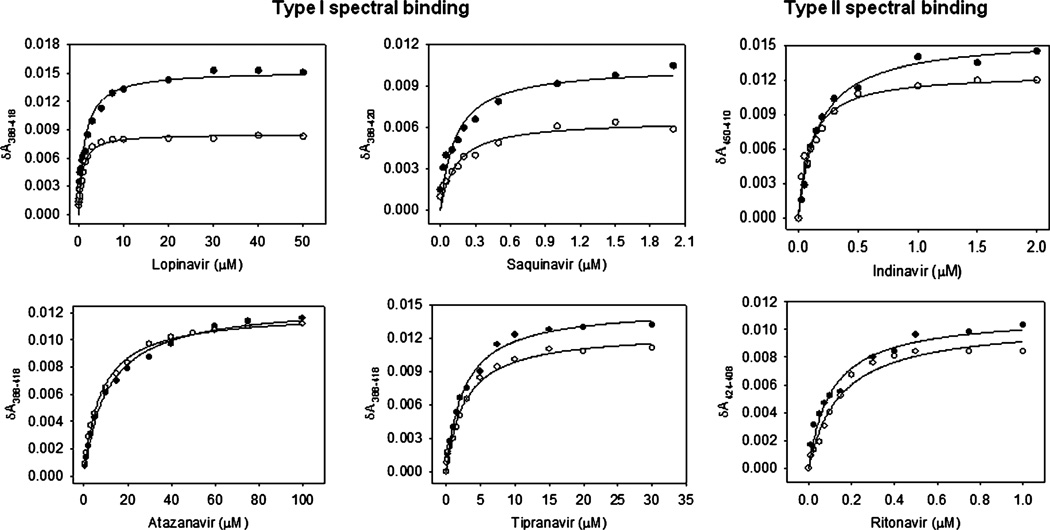

We examined the role of ethanol on CYP3A4 spectral binding of 8 PIs, which differ in their physicochemical properties such as shape, size, polarity, and hydrophobicity (Fig. 1). Atazanavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir showed type I spectral binding, whereas indinavir and ritonavir showed type II spectral binding (Fig. 2). Atazanavir and tipranavir also showed a weak type II spectral binding at low concentrations (<0.5 µM) (data not shown). Amprenavir and darunavir did not show detectable spectral binding. Interestingly, indinavir showed type II spectral binding at 450 to 410 nm as opposed to 424 to 408 nm, which is the characteristic of imidazole–heme covalent binding (Fig. 2). All the PIs showed maximum spectral change (δAmax) of 0.011 to 0.016, which are approximately 25 to 35% of the total spectral binding with CYP3A4 (Fig. 1, Table 1). A 100% spectral binding with 0.5 µM CYP3A4 should yield δAmax of approximately 0.045. Overall, the results indicated that atazanavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir are type I PIs, indinavir and ritonavir are type II PIs, and amprenavir and darunavir do not show spectral change (spectrally unbound PIs) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Ball and stick structures of type I, type II, and spectrally unbound protease inhibitors (PIs). The structures were created using ChemDraw Ultra 6.0.6 (PerkinElmer, Cambridge, MA).

Fig. 2.

Spectral binding of CYP3A4 by type I PIs (left panel a) and type II PIs (right panel) in the absence (filled circles) and presence of 20 mM ethanol (open circles). The spectral binding was performed at varying concentrations of atazanavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir. The δAmax and KD are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Spectral Binding of Protease Inhibitors (PIs) with CYP3A4 in the Absence and Presence of 20 mM Ethanol

| No ethanol | 20 mM ethanol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIs | δAmax | KD (µM) | δAmax | KD (µM) |

| Type I | ||||

| Atazanavir | 0.013 ± 0.0003 | 10.9 ± 0.84 | 0.012 ± 0.0002 | 7.78 ± 0.49 |

| Lopinavir | 0.015 ± 0.0005 | 1.35 ± 0.19 | 0.009 ± 0.0002 | 0.766 ± 0.081 |

| Saquinavir | 0.011 ± 0.0001 | 0.140 ± 0.026 | 0.006 ± 0.0003 | 0.128 ± 0.025 |

| Tipranavir | 0.015 ± 0.0003 | 2.62 ± 0.17 | 0.012 ± 0.0003 | 2.74 ± 0.21 |

| Type II | ||||

| Indinavir | 0.016 ± 0.0004 | 0.167 ± 0.013 | 0.013 ± 0.0005 | 0.102 ± 0.016 |

| Ritonavir | 0.011 ± 0.0005 | 0.107 ± 0.015 | 0.011 ± 0.0006 | 0.114 ± 0.021 |

Standard errors for fit to a single-site ligand binding are shown as ±. Results are the representative of at least 2 independent determinations. The variation between the experiments is <20%.

Ethanol (20 mM) showed approximately 50% decrease in δAmax with type I lopinavir and saquinavir; however, it did not show a decrease in δAmax with type I atazanavir and tipranavir (Fig. 2, Table 1). The δAmax values of type II indinavir and ritonavir were also unaltered. Ethanol did not alter binding affinity (KD) of type I PIs, except tipranavir in which ethanol decreased the KD by approximately 50% (0.766 ± 0.081 vs. 1.35 ± 0.19 µM) (Table 1). Similarly, while ethanol decreased the KD of type II PI, indinavir (0.102 ± 0.016 vs. 0.167 ± 0.013 µM), it did not change the KD of ritonavir.

Effect of Ethanol on CYP3A4 Inhibition by PIs

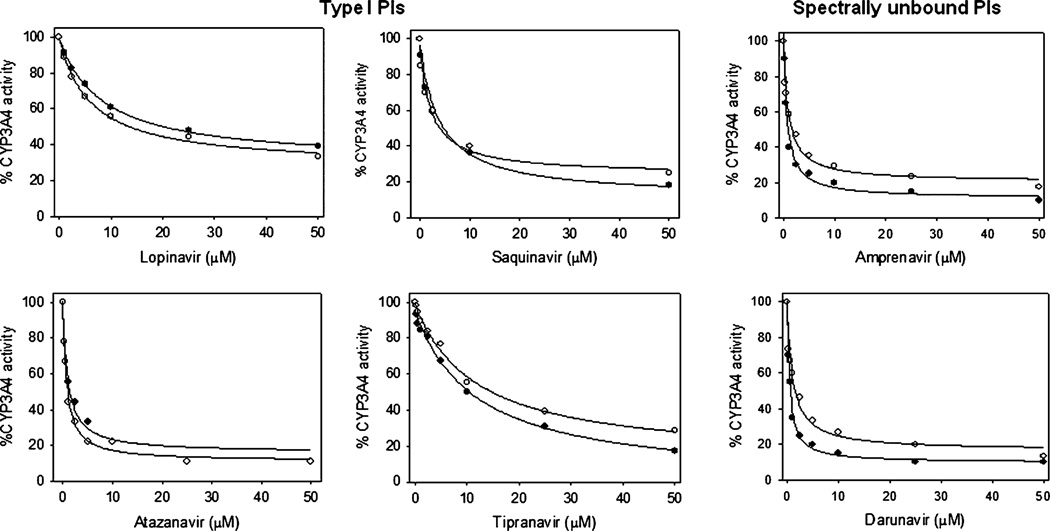

To further examine the effect of ethanol on PIs–CYP3A4 interaction, we performed CYP3A4 inhibition by all the 8 PIs using 7-BFC debenzylation reaction. The results are presented in Figs. 3 and 4 and Table 2. As expected, all the PIs inhibited CYP3A4 activity, with strongest inhibition by ritonavir (IC50 = 0.10 ± 0.04 µM). Amprenavir and darunavir also showed strong inhibition, with the IC50 values of <1 µM. On the other hand, all type I PIs and type II indinavir showed an IC50 of ≥1 µM. Their inhibition affinity was in this order: atazanavir>saquinavir>indinavir>lopinavir>tipranavir (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of CYP3A4 by type I and spectrally unbound PIs in the absence (filled circles) and presence of 20 mM ethanol (open circles). The inhibition was performed at varying concentrations of atazanavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, tipranavir, amprenavir, and darunavir using 7-BFC substrate in the standard NADPH reaction. The 100% CYP3A4 activity corresponds to approximately 3.5 nmoles/min/nmol P450. The IC50 values are presented in Table 2A.

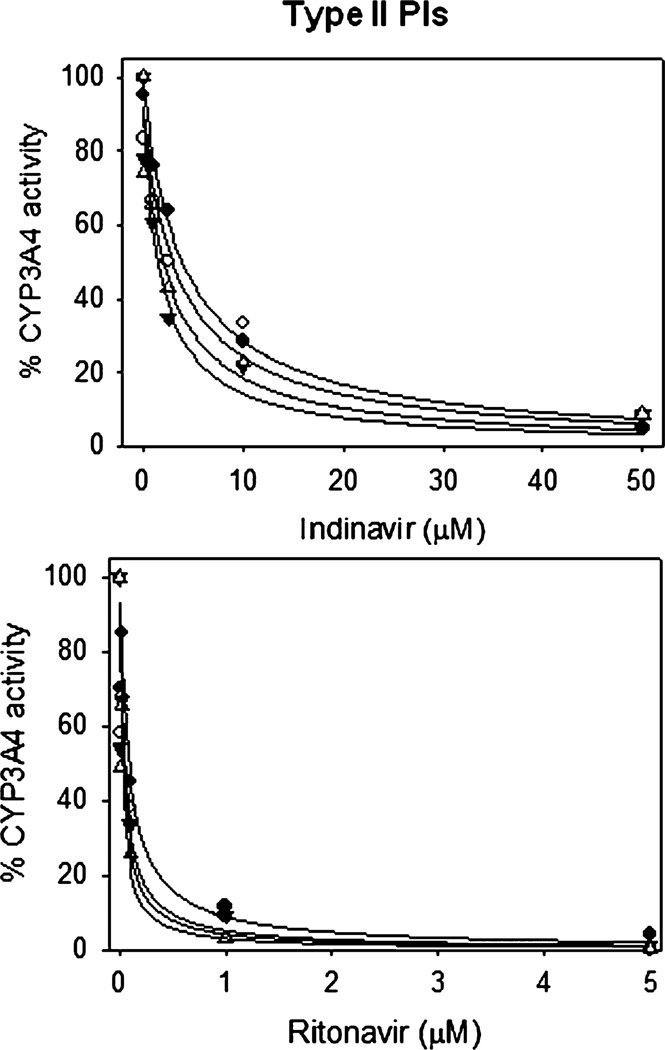

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of CYP3A4 by type II PIs at 0 mM (filled circles), 5 mM (open circles), 10 mM (filled triangles), and 20 mM (open triangles) ethanol. The inhibition was performed at varying concentrations of indinavir and ritonavir using 7-BFC substrate in the standard NADPH reaction. The 100% CYP3A4 activity corresponds to approximately 3.5 nmoles/min/nmol P450. The IC50 values are presented in Table 2B.

Table 2.

Inhibition of CYP3A4 with Protease Inhibitors (PIs). (A) Type I and Spectrally Unbound PIs at 0 and 20 mM Ethanol. (B) Type II PIs at Different Ethanol Concentrations

| (A) | ||

|---|---|---|

| PIs | IC50 (µM) | |

| Type I | No Ethanol | 20 mM Ethanol |

| Atazanavir | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.85 ± 0.2 |

| Lopinavir | 8.2 ± 0.5 | 6.2 ± 0.8 |

| Saquinavir | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| Tipranavir | 11 ± 2.0 | 12 ± 1.8 |

| Amprenavir | 0.69 ± 0.17 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Darunavir | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| (B) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (mM) | IC50 (µM) | |

| Indinavir | Ritonavir | |

| 0 | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 0.10 ± 0.04 |

| 5 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 0.06 ± 0.03 |

| 10 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 0.05 ± 0.02 |

| 20 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

Standard errors for fit to a single-site ligand binding are shown as ±. Results are the representative of at least 2 independent determinations. The variation between the experiments is <25%.

Ethanol (20 mM) did not significantly alter the IC50 of type I PIs (atazanavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir), while it markedly increased the IC50 of spectrally unbound PIs (amprenavir and darunavir) (Fig. 3, Table 2). Interestingly, 20 mM ethanol decreased the IC50 of type II PIs (indinavir and ritonavir) by 2- to 3-fold (Fig. 4, Table 2). To further confirm that the effect of ethanol on PIs’ inhibition is specific, we performed CYP3A4 inhibition by 2 representative PIs, indinavir and ritonavir, at multiple ethanol concentrations. The results showed that ethanol decreased the IC50 values of indinavir and ritonavir in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4, Table 2B).

DISCUSSION

This is the first comprehensive study of spectral binding and inhibition of CYP3A4 with all the clinically available PIs (amprenavir, atazanavir, darunavir, indinavir, lopinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir). In addition, we have examined the role of ethanol in CYP3A4 spectral binding and inhibition with these PIs. Our results suggest a differential role of ethanol on spectral binding and inhibitory characteristics of type I (atazanavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir), type II (indinavir and ritonavir), and spectrally unbound (amprenavir and darunavir) PIs. The altered binding and inhibition of CYP3A4 with these PIs may have implications on their metabolism and efficacy in alcoholic HIV-1-infected individuals.

Ligands with different physicochemical properties have abilities to bind CYP active site in different ways and show type I, type II, or no spectral binding (Muralidhara et al., 2006; Renaud et al., 1996; Roberts et al., 2005). In this context, ritonavir showed type II spectral binding because of the presence of thio-imidazole group, which has an ability to covalently bind to CYP3A4 heme (Fig. 1). As indinavir has a pyridine group, it also showed type II spectral binding, but at different wavelengths. However, in atazanavir and tipranavir, the presence of neighboring bulky substituents with pyridine group may be associated with a weak type II spectral binding at low concentrations and type I spectral binding at high concentrations (Fig. 1). Lopinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir do not have such substituents and therefore, showed type I spectral binding (Fig. 1). As these PIs showed only 25 to 35% of the total spectral change, it appears that approximately one-third of the CYP3A4 populations are available for spectral binding. This is not surprising because we have shown earlier that CYP3A4 exists in multiple populations and they are in equilibrium based on the interactions with specific ligands (Davydov and Halpert, 2008; Kumar et al., 2005).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on spectral characterizations of these PIs with CYP3A4, except for indinavir (Hosea et al., 2000). In the previous study, indinavir showed type II spectral binding with very high affinity (KD = 0.3 µM), which is similar to the KD reported in our study (Table 1). Recently, we have studied the spectral binding of another PI, nelfinavir, which showed a high-affinity type I spectral binding with CYP3A4 (Kumar et al., 2010). As expected, type II PIs showed higher affinity than most of the type I PIs. As an exception, type I saquinavir also showed high affinity perhaps because of additional interactions with side chains of CYP3A4. As only one-third CYP3A4 population (0.17 µM) is available to bind indinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir (KD = 0.1 to 0.16 µM), these compounds appear to bind CYP3A4 in 1:1 ratio. These results are consistent with earlier reports that indinavir and nelfinavir bind CYP3A4 in 1:1 ratio (Hosea et al., 2000; Kumar et al., 2010).

In contrast to spectral binding, inhibition of CYP3A4 by several PIs has been studied (Eagling et al., 1997; Granfors et al., 2006; Pal and Mitra, 2006; Rittweger and Arastéh, 2007; Xu and Desai, 2009; Zhou et al., 2005). As previously reported (Xu and Desai, 2009; Zhou et al., 2005), our study also confirmed that ritonavir is the most potent inhibitor of CYP3A4. Our results are consistent with other studies that amprenavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, and saquinavir are also potent inhibitors of CYP3A4 (Eagling et al., 1997; Granfors et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2005). However, variable IC50 or KI values of these PIs in different studies appear to be related to the differences in substrates used for activity determinations. Although darunavir has been shown to be an inhibitor of CYP3A4, its inhibitory characteristic is not well studied (Rittweger and Arastéh, 2007). In addition, inhibition of CYP3A4 by atazanavir and lopinavir has not been studied. Our study suggested that atazanavir and darunavir are potent inhibitors, while lopinavir is relatively a weak inhibitor of CYP3A4.

We have previously shown that ethanol exhibits type I spectral binding with CYP3A4 and decreases δAmax of type I nelfinavir (Kumar et al., 2010). As expected, ethanol decreased the δAmax of lopinavir and saquinavir. However, it did not decrease the δAmax of atazanavir and tipranavir, perhaps because they also showed type II binding at low concentrations. Although ethanol did not alter the spectral binding affinity of most of the PIs, it facilitated the inhibition of type II PIs, markedly reduced the inhibition of spectrally unbound PIs, and exhibited no effects on the inhibition of type I PIs. Based on these results, we propose the following models for ethanol (EtOH)–CYP3A4–PIs three-way interactions with type I PI (TIPI) and type II (TIIPI). ϕ, ↑, and ↓ stands for no change, increase, and decrease, respectively.

Ethanol and type I PIs interact with CYP3A4 independently, however, ethanol and type I PIs does not interact with each other, resulting into a decrease in the extent of spectral binding without altering the inhibition of CYP3A4 (model A). Type II PIs replace ethanol from CYP3A4 heme, and the replaced ethanol appears to further interact with these PIs synergistically to facilitate the inhibition of CYP3A4 (model B). However, the mechanism by which ethanol interacts with these PIs is unknown. We hypothesize that ethanol replaces water molecules and facilitates CYP3A4–type II PIs interaction through additional H-bonds and/or hydrophobic interactions. Our hypothesis is consistent with the fact that ethanol is known to interact with proteins through H-bond and stabilize hydrophobic interactions by removing water molecules present in the active site of CYP3A4 (Dwyer and Bradley, 2000; Kumar et al., 2010).

As reported earlier for nelfinavir (Kumar et al., 2010), a decrease in the magnitude of spectral binding with lopinavir and saquinavir and an increase in the binding affinity for CYP3A4 inhibition by indinavir and ritonavir may alter the metabolism of these drugs by CYP3A4 in the liver as well as macrophages. The altered inhibition of CYP3A4 by these PIs may also alter the metabolism of other PIs or NNRTIs. These may eventually lead to diminished efficacy of the HAART and increased toxicity. This is an important finding in context with the report that alcohol is known to increase toxicity and reduce efficacy of the HAART in HIV-1-infected individuals (Flexner et al., 2002; Kalichman et al., 2009; Kresina et al., 2002; Miguez et al., 2003; Shibata et al., 2004). More specifically, the studies from Flexner and colleagues (2002) and Shibata and colleagues (2004) have shown that alcohol can increase the metabolism and decrease the bioavailability of PIs and NNRTIs, resulting into decreased efficacy. However, the mechanism by which it occurs is not known, except the fact that alcohol is capable of inducing CYP3A4, which may lead to increased metabolism of PIs and NNRTIs. The presence of multiple PIs and/or NNRTIs in HAART regimen, in which PIs also act as CYP3A4 inhibitors, make alcohol–CYP3A4–PIs interactions complex. Therefore, this study provides the first step to understand the overall effect of ethanol on the metabolism, bioavailability, and efficacy of PIs and NNRTIs in HIV-1-infected individuals who are chronic mild-to-moderate alcohol users.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. James Halpert from Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California San Diego for providing CYP3A4, CPR, and b5 containing plasmids. We thank Dr. Fei P. Gao, KU Higuchi Bioscience Center, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, for expression and purification of CPR and b5 proteins. We also thank Dr. Ravindra Earla for making the structures of the PIs shown in Fig. 1. This work was supported by School of Pharmacy, UMKC University of Missouri Research Board to SK, and NIAAA (AA015045) to AK.

REFERENCES

- Acosta EP. Pharmacokinetic enhancement of protease inhibitors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:S11–S18. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200202011-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzenbacher P, Anzenbacherová E. Cytochromes P450 and metabolism of xenobiotics. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;58:737–747. doi: 10.1007/PL00000897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvieux C, Tribut O. Amprenavir or fosamprenavir plus ritonavir in HIV infection: pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability profile. Drugs. 2005;65:633–659. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croom KF, Dhillon S, Keam SJ. Atazanavir: a review of its use in the management of HIV-1 infection. Drugs. 2009;69:1107–1140. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969080-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxtall JD, Perry CM. Lopinavir/ritonavir: a review of its use in the management of HIV-1 infection. Drugs. 2010;70:1885–1915. doi: 10.2165/11204950-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DR, Halpert JR. Allosteric P450 mechanisms: multiple binding sites, multiple conformers or both? Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4:1523–1535. doi: 10.1517/17425250802500028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. The history of antiretrovirals: key discoveries over the past 25 years. Rev Med Virol. 2009a;19:287–299. doi: 10.1002/rmv.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. Anti-HIV drugs: 25 compounds approved within 25 years after the discovery of HIV. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009b;33:307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanski TL, He YA, Khan KK, Roussel F, Wang Q, Halpert JR. Phenylalanine and tryptophan scanning mutagenesis of CYP3A4 substrate recognition site residues and effect on substrate oxidation and cooperativity. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10150–10160. doi: 10.1021/bi010758a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer DS, Bradley RJ. Chemical properties of alcohols and their protein binding sites. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:265–275. doi: 10.1007/PL00000689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagling VA, Back DJ, Barry MG. Differential inhibition of cytochrome P450 isoforms by the protease inhibitors, ritonavir, saquinavir and indinavir. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:190–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexner CW, Cargill VA, Sinclair J, Kresina TF, Cheever L. Alcohol use can result in enhanced drug metabolism in HIV pharmacotherapy. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2002;15:57–58. doi: 10.1089/108729101300003636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser AG. Pharmacokinetic interactions between alcohol and other drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:79–90. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199733020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavegnano C, Schinazi RF. Antiretroviral therapy in macrophages: implication for HIV eradication. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2009;20:63–78. doi: 10.3851/IMP1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granfors MT, Wang JS, Kajosaari LI, Laitila J, Neuvonen PJ, Backman JT. Differential inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4, 3A5 and 3A7 by five human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitors in vitro. Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow GR, Halpert JR. Analysis of human cytochrome P450 3A4 cooperativity: construction and characterization of a site-directed mutant that displayes hyperbolic steroids hydroxylation kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6636–6641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosea NA, Miller GP, Guengerich FP. Elucidation of distinct ligand binding sites for cytochrome P450 3A4. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5929–5939. doi: 10.1021/bi992765t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Nácher I, García B, Barreiro P, Rodriguez-Novoa S, Morello J, González-Lahoz J, de Mendoza C, Soriano V. Trends in the prescription of antiretroviral drugs and impact on plasma HIV-RNA measurements. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:816–822. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Arya P, Patel K, Singh B, Silverstein P, Bhat H, Kumar A, Kumar S. Effect of alcohol on drug efflux protein and drug metabolic enzymes in U937 macrophages. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, Swetsze Pope CH, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, Eaton L. Prevalence and clinical implications of interactive toxicity beliefs regarding mixing alcohol and antiretroviral therapies among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:449–454. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresina TF, Flexner C, Sinclair WJ, Correia MA, Stapleton JT, Adeniyi-Jones S. Alcohol use and HIV pharmacotherapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2002;18:757–770. doi: 10.1089/08892220260139495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Davydov DR, Halpert JR. Role of cytochrome b5 in modulating peroxide-supported CYP3A4 activity: evidence for a conformational transition and cytochrome P450 heterogeneity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1131–1136. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Earla R, Jin M, Mitra AK, Kumar A. Effect of ethanol on spectral binding, inhibition, and activity of CYP3A4 with an antiretroviral drug nelfinavir. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Liu H, Halpert JR. Engineering of cytochrome P450 3A4 for enhanced peroxide-mediated substrate oxidation using directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:1958–1965. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.012054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeage K, Perry CM, Keam SJ. Darunavir: a review of its use in the management of HIV infection in adults. Drugs. 2009;69:477–503. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguez MJ, Shor-Posner G, Morales G, Rodriguez A, Burbano X. HIV treatment in drug abusers: impact of alcohol use. Addict Biol. 2003;8:33–37. doi: 10.1080/1355621031000069855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidhara BK, Negi S, Chin CC, Braun W, Halpert JR. Conformational flexibility of mammalian cytochrome P450 2B4 in binding imidazole inhibitors with different ring chemistry and side chains. Solution thermodynamics and molecular modeling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8051–8061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal D, Mitra AK. MDR- and CYP3A4-mediated drug-drug interactions. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:323–339. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud JP, Davydov DR, Heirwegh KP, Mansuy D, Hui Bon Hoa GH. Thermodynamic studies of substrate binding and spin transitions in human cytochrome P-450 3A4 expressed in yeast microsomes. Biochem J. 1996;319:675–681. doi: 10.1042/bj3190675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittweger M, Arastéh K. Clinical pharmacokinetics of darunavir. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46:739–756. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200746090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AG, Campbell AP, Atkins WM. The thermodynamic landscape of testosterone binding to cytochrome P450 3A4: ligand binding and spin state equilibria. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1353–1366. doi: 10.1021/bi0481390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts NA, Craig JC, Duncan IB. HIV protease inhibitors. Biochem Soc Trans. 1992;20:513–516. doi: 10.1042/bst0200513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N, Kageyama M, Kimura K, Tadano J, Hukushima H, Namiki H, Yoshikawa Y, Takada K. Evaluation of factors to decrease plasma concentration of an HIV protease inhibitor, saquinavir in ethanol-treated rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:203–209. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talakad JC, Kumar S, Halpert JR. Decreased susceptibility of the cytochrome P450 2B6 variant K262R to inhibition by several clinically important drugs. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:644–650. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walubo A. The role of cytochrome P450 in antiretroviral drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Toxicol. 2007;3:583–598. doi: 10.1517/17425225.3.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathermon R, Crabb DW. Alcohol and medication interactions. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:40–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Desai MC. Pharmacokinetic enhancers for HIV drugs. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:775–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Yung Chan S, Cher Goh B, Chan E, Duan W, Huang M, McLeod HL. Mechanism-based inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 by therapeutic drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:279–304. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]