Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) causes brain degeneration, primarily depleting cholinergic cells, and leading to cognitive and learning dysfunction. Logically, to augment the cholinergic cell loss, a viable treatment for AD has been via drugs boosting brain acetylcholine production. However, this is not a curative measure. To this end, nerve growth factor (NGF) has been examined as a possible preventative treatment against cholinergic neuronal death while enhancing memory capabilities; however, NGF brain bioavailability is challenging as it does not cross the blood–brain barrier. Investigations into stem cell- and gene-based therapy have been explored in order to enhance NGF potency in the brain. Along this line of research, a genetically modified cell line, called HB1.F3 transfected with the cholinergic acetyltransferase or HB1.F3.ChAT cells, has shown safety and efficacy profiles in AD models. This stem cell transplant therapy for AD is an extension of the neural stem cells' use in other neurological treatments, such as Parkinson's disease and stroke, and recently extended to cancer. The HB1 parent cell and its associated cell lines have been used as a vehicle to deliver genes of interest in various neurological models, and are highly effective as they can differentiate into neurons and glial cells. A focus of this mini-review is the recent demonstration that the transplantation of HB1.F3.ChAT cells in an AD animal model increases cognitive function coinciding with upregulation of acetylcholine levels in the cerebrospinal fluid. In addition, there is a large dispersion throughout the brain of the transplanted stem cells which is important to repair the widespread cholinergic cell loss in AD. Some translational caveats that need to be satisfied prior to initiating clinical trials of HB1.F3.ChAT cells in AD include regulating the host immune response and the possible tumorigenesis arising from the transplantation of this genetically modified cell line. Further studies are warranted to test the safety and effectiveness of these cells in AD transgenic animal models. This review highlights the recent progress of stem cell therapy in AD, not only emphasizing the significant basic science strides made in this field, but also providing caution on remaining translational issues necessary to advance this novel treatment to the clinic.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Neural stem cell, Neural growth factor, ChAT cells, Gene therapy

Pathology of Alzheimer's disease

The degeneration and loss of cholinergic neurons and synapses encompassing the brain is a major pathological feature of Alzheimer's disease (AD); this neuronal death is prominently present throughout the basal forebrain, amygdala, hippocampus, and cortical area. As memory and cognitive function declines over time, dementia ensues and patient deaths are accelerated (Bartus et al., 1982; Coyle et al., 1983; Whitehouse et al., 1981). The only effective treatments currently available are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, which augment cholinergic function. However, such pharmacologic treatments merely afford palliative relief, and not a curative one.

Elucidating cell death mechanisms implicated in the pathogenesis of AD may reveal novel therapeutic targets for the disease. One such disease pathway embraces the amyloid cascade hypothesis, which proposes that increased levels of both soluble and insoluble Aβ peptides triggermemory deficits; these peptides are derived from the larger amyloid precursor protein (APP) by sequential proteolytic processing (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). The use of anti-Aβ antibody to treat APP mice, a transgenic mouse model of AD, has been shown to completely restore hippocampal acetylcholine release and high-affinity choline uptake, while also improving habituation learning (Bales et al., 2006). A clinical trial in AD patients has been initiated based on these findings.

In the same vein of lessening the Aβ burden in AD, experimental therapeutic approaches for AD have pursued chronically decreasing Aβ, through Aβ-degrading proteinases, such as neprilysin (Iwata et al., 2001), insulin-degrading enzyme (Farris et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2003), plasmin (Melchor et al., 2003), and cathepsin B (Mueller-Steiner et al., 2006). As a proof-of-concept, Aβ deposits were reduced by intracerebral injection of a lentivirus vector expressing human neprilysin in transgenic mouse models of amyloidosis (Marr et al., 2003). Additionally, the over-expression of the human neprilysin gene in intracerebrally injected fibroblasts into the brain of Aβ transgenic mice with advanced plaque deposits was found to significantly reduce the amount of amyloid plaque in the brain (Hemming et al., 2007). Though the use of Aβ-degrading proteases to lower Aβ levels is supported by these studies, further investigation is needed to examine ex vivo delivery of protease genes using human neural stem cells (NSCs) for the treatment of AD. In tandem with sequestering excess Aβ in the brain, a preventative approach against neurodegeneration has been tested using nerve growth factor (NGF), which impedes neuronal death and enhances memory in animal models of aging, excitotoxicity, and amyloid toxicity (Emerich et al., 1994; Fischer et al., 1987; Hefti, 1986; Tuszynski, 2002; Tuszynski et al., 1990). Indeed, NGF has been shown to retard neuronal degeneration and cell death treatment in AD. However, NGF does not cross the blood–brain barrier, thereby prompting a research need to find a strategy to increase NGF bioavailability in the brain. Employing a gene therapy approach, such as an ex vivo therapy, NGF can be given directly to the brain and has been shown to diffuse for a distance of 2–5 mm (Tuszynski et al., 1990). A phase 1 clinical trial consisting of eight mild-AD patients were exposed to an ex vivo NGF gene treatment involving the transplantation into the forebrain of autologous fibroblasts genetically modified to express human NGF (Tuszynski et al., 2005). Following an average of 22 months, months, there were no long-term adverse effects observed. An improvement in the rate of cognitive decline was suggested by evaluation of Mini-Mental Status Examination and Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subcomponent (Tuszynski et al., 2005). Substantial increases in cortical fluorodeoxyglucose following treatment were also observed using serial PET scans (Tuszynski et al., 2005). Stem cells have the ability to carry new genes through genetic modification and have high migratory capacity following transplantation into the brain (Flax et al., 1998; Kim, 2004; Lee et al., 2008). Moreover, the highly migratory active stem cells have been shown to substitute for the routinely immobile fibroblasts as a delivery vehicle for NGF to protect against the degeneration of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (Kang et al., 1993).

Cell therapy for neurological disorders

NSC cell therapy for AD is an offshoot of the general concept of transplanting NSC in many neurological disorders. Indeed, over the past two decades, studies have begun to examine stem cell-based therapies as a novel strategy to treat brain disorders such as Parkinson disease (PD), Huntington disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), stroke and spinal cord injury (Goldman, 2005; Kim and de Vellis, 2009; Lindvall and Kokaia, 2006). Stem cell-based cell therapy has been linked to the prevention or delay host cell death and restore injured tissue (Blurton-Jones et al., 2009; Goldman, 2005; Kim and de Vellis, 2009; Lindvall and Kokaia, 2006). Previous studies have shown the preservation of host neurons and recovery of function through the transplantation of human NSCs expressing diverse functional genes, especially growth factors, in animal models of PD, ALS, stroke and spinal cord injury (Hwang et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2007, 2008, 2009a,2009b, 2010; Yasuhara et al., 2006). Due to their high survival rate and ability to differentiate into both neurons and glial cells following transplantation into damaged tissue, human NSCs have emerged as highly-effective source of cells for genetic manipulation and gene transfer into the CNS ex vivo (Kim, 2004; Kim and de Vellis, 2009).

Neural transplantation of fetal dopaminergic neurons was tested as an experimental clinical therapy for PD (Borlongan, 2000; Borlongan et al., 1999; Freeman et al., 1995; Kordower et al., 1995; Lindvall et al., 1988, 1992; Madrazo et al., 1988). However, the logistical issues, associated with procuring large supply of fetal cells, overshadow its therapeutic benefit (Borlongan and Sanberg, 2002; Freed, 2002). Finding an unlimited source of transplantable cells would be a welcome advance in cell therapy. In this regard, stem cell's infinite ability to self-renew and differentiate into neurons makes the search for cell therapy crucial to the next step of clinical application (Arenas, 2002; Bjorklund et al., 2002; Langston, 2005; Lindvall and Bjorklund, 2004; Snyder and Olanow, 2005; Sonntag et al., 2005; Takagi et al., 2005). Although there is absent or minimal detection of fully mature neuronal differentiation of stem/progenitor cells, attenuation of disease symptoms has been observed, possibly as a result of the secretion of neurotrophic factors by the cells (Goldman, 2005; Jung et al., 2004; Rafuse et al., 2005). As a growth factor secretory cell, human HB1.F3 NSCs have been investigated as graft source for PD; transplantation of HB1.F3 cells into the striatum of rats with dopamine-depleted nigrostriatal pathway produced by the neurotoxin 6-OHDA significantly ameliorated parkinsonian behavioral symptoms compared with controls via neurotrophic factor secretion among other neurorestorative processes (Yasuhara et al., 2006).

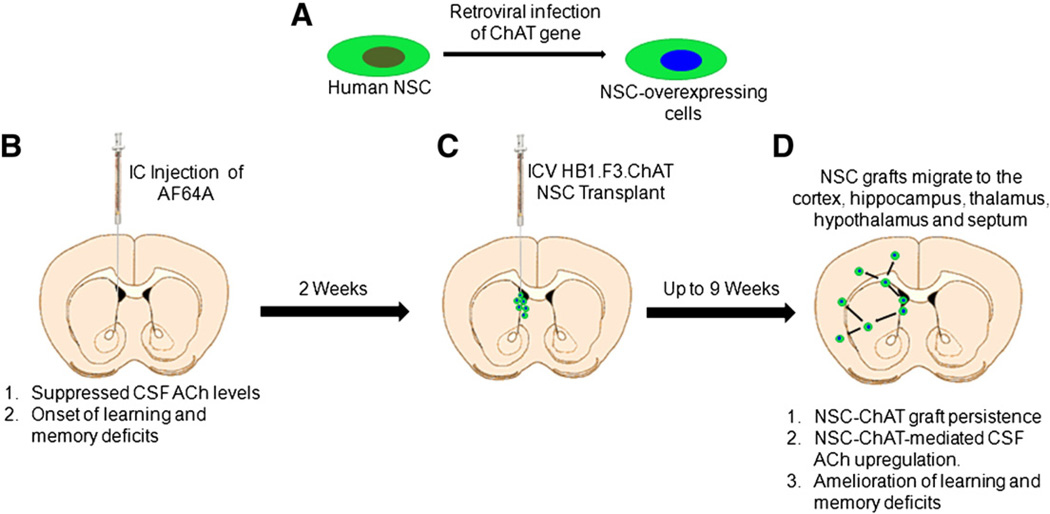

Recently, Dr. Kim and colleagues (Park et al., 2012a) extended the use of HB1.F3 cells to AD by over-expressing human choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) gene in this NSC line. Using a neurotoxin rat AD model in which ethylcholine mustard aziridinium ion (AF64A) was intracerebroventricularly into the animal's brain, widespread cholinergic neuronal loss was detected and accompanied by memory deficits, resembling many of the salient features of AD. In contrast, transplantation of HB1.F3.ChAT NSCs into the AF64A-lesioned rats led to recovery of the learning and memory function, and induced elevated levels of acetylcholine (ACh) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Upon further investigation, the migration of the transplanted F3.ChAT human NSCs was traced to various regions of the brain including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, striatum and septum; these cells were seen to differentiate into neurons and astrocytes. As seen in this study, memory deficits and complex learning impairments are corrected by transplantation of human NSCs over-expressing ChAT in the brains of AF64A-cholinotoxin-induced AD rat model (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of NSC transplantation and therapeutic pathway in AD. Human NSC line is transfected by gene of interest, in the case of AD, the ChAT gene is over-expressed in the cell line (A). Animal model of AD is created by ICV injection of AF64A cholinotoxin in the rat brain causing widespread cholinergic cell death, downregulation of ACh levels in the CSF, and impairments in learning and memory, reminiscent of AD (B). Two weeks later, AF64A-lesioned rats receive ICV transplantation of ChAT-overexpressing NSCs or the parent NSCs (C). From 4 weeks up to at least 9 weeks post-transplantation, AF64A-lesioned rats receiving transplantation of ChAT-overexpressing NSCs but not the parent NSCs display NSC-ChAT graft persistence, CSF ACh upregulation, and amelioration of learning and memory deficits (D).

One of the major findings of this study (Park et al., 2012a) is the expression of mRNA in F3.ChAT cells. Additionally, protein synthesis of ChAT was much higher (>10 times) than basic F3 cells. The ChAT protein was detected throughout various brain regions in transplanted F3.ChAT cells, surviving for up to 9 weeks in vivo. This diffusion of the transplanted NSCs in the brain could possibly be influenced by the destruction of multiple cholinergic systems by a specific cholinotoxin AF64A, and injury-site tropism of F3 NSCs triggered by chemo-attractants such as hepatocyte growth factor, stromal cell-derived factor-1, vascular endothelial cell growth factor, and stem cell factor (Kim and de Vellis, 2009; Schmidt et al., 2005; Shimato et al., 2007). This study also suggests that F3.ChAT human NSCs express high ChAT mRNA, which likely stimulated the high levels of ACh in CSF. Implantation of F3.ChAT (1 × 106 cells/rat), but not the parent F3 cells, fully restored the ACh level in the brain, facilitating amelioration of cognitive functions of AF64A-treated rats, comparable to normal animals. By comparison, F3 parental cells only slightly elevated CSF ACh content, yet adversely affected cognitive function.

NSC transplantation has been shown to correlate to the improvement of cognitive function in AD model animals through the enhancement of hippocampal synaptic density, mediated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Blurton-Jones et al., 2009; Xuan et al., 2008). In addition, previous studies revealed that NSCs and neural progenitor cells which express NGF restored learning and memory function in AD animals (Srivastava et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2008). From these studies, it seems that various neurotrophic factors such as NGF and BDNF play important function of neuroprotection and brain repair in AD model animals (Beck et al., 1995; Schäbitz et al., 2000). Previous studies have shown that F3 human NSCs expressing neurotrophic factors, not only BDNF, but also neurotrophin-3, glial cell line-derived growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor, protected host neurons in animal models of hemorrhagic stroke (Lee et al., 2007, 2008), PD (Yasuhara et al., 2006) and ALS (Hwang et al., 2009).

In this study (Park et al., 2012a), grafted human NSCs migrate extensively from the cerebral ventricle into the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and striatum with >96% differentiated into neurons, while less than 4% committed into the astrocytic lineage. In spite of these high efficiencies observed, there have been some clinical setbacks in the involvement of human NSCs in therapy. It has proven difficult to employ the oncogene (v-myc) and a viral vector (retrovirus) for generation of this cell line, and therefore drives down the efficiency of this genetically modified NSCs for clinical application. This problem can be overcome by utilizing patient-derived autologous cells; this not only enhances survival rate by avoiding immune rejection, but also solicits the need for functional gene-inserting technique such as electroporation in place of viral vectors. Through this process, it seems that using genetically modified human NSCs for cell replacement and gene transfer to the brain of patients could implement a possible clinical basis for the development of potentially powerful new therapeutic strategies for AD patients.

There are many novel scientific advances that can be inferred from this study (Park et al., 2012a). First, the use of clinical grade human stem cells should allow guidance on the design of future clinical trials of cell therapy for AD. Second, these observations also lend support to on-going clinical trials of same parent cells in cancer therapy (Frank et al., 2009; Gutova et al., 2010, 2012; Seol et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2012). That these cells are safe and effective in an animal model of AD, and with good safety profile from the limited clinical trials in cancer (see below), should expedite the translation to clinical application of these cells in AD. Third, the use of genetically engineered cells in clinical trials in neurological disorders has recent precedence. Preclinical studies of genetically manipulated cells have shown similar therapeutic potential in animal models of stroke. In particular, transplantation of Notch-induced SB623 and c-mycERTAM retrovirally infected CTX0E03 by SanBio (Yasuhara et al., 2009) and Reneuron (Stroemer et al., 2009), respectively, has been shown to be safe and effective in animal models of stroke. Fourth, the reported multipronged mechanism involving ChAT secretion coupled with neural differentiation caters to the multiple-hit hypothesis of AD, in that various cell death pathways will require several therapeutic processes in order to arrest the disease cascade of events. Altogether, the findings here not only advance both our basic science understanding of AD pathology, but also offer translational guidance into the clinical application of a genetically modified cell line for transplantation in AD patients.

This study by Dr. Kim and colleagues (Park et al., 2012a) is a part of a series of safety and efficacy study for the use of this cell line in different animal models of AD (Lee et al., 2012; Park et al., 2012b). In parallel to the AF64A neurotoxin AD model utilized here, the same authors have observed similar results of therapeutic efficacy of the F3.ChAT cells in the kainic acid AD model (Park et al., 2012b). The proof-of-concept of genetically engineered cells to harbor not only neurotransmitter secreting genes but also growth factor secreting cells has been demonstrated in these studies (Park et al., 2012a, 2012b). Indeed, it has been shown that NGF-overexpression in F3 cell lines also promoted rescue of cognitive impairment in AD model (Lee et al., 2012). As noted above, future studies may reveal that the combination of neurotransmitter and growth-factor secreting genetically engineered cells may improve efficacy of cell therapy in AD which may be mediated by multiple cell death pathways requiring a multi-pronged approach targeting these degenerative processes.

On December 5, 2007, the NIH Recombinant cDNA (CD) Advisory Committee (NIH RAC) approved an application of the City of Hope Medical Center (Duarte, CA) to conduct a clinical trial in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma using immortalized human NSCs which were retrovirally transduced to express the CD therapeutic transgene (Aboody et al., 2008). As seen in previous animal models, the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of human NSCs to track invasive tumor cells, distant microtumor foci and deliver therapeutic gene products to tumor cells could provide an effective antitumor response. Therefore, the use of NSCs could overcome several obstacles impeding the current therapy, specifically gene therapy. In this pilot study in California, the safety and feasibility of such an immortalized human NSC line (HB1.F3) that expresses the enzyme CD are being tested in 10 patients with recurrent glioma. It is envisioned that the transplanted NSCs will distribute throughout the primary tumor site, and, within 5 days, colocalize with the infiltrating tumor cells. An oral prodrug (5-fluorocytosine, administered on the fifth day for 7 days) will be converted to the chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil by NSCs expressing CD. The CD will be secreted from the tumor site producing an antitumor effect. The experience gained from this cancer clinical trial will help guide the use of this HB1.F3 cells in AD patients.

Caveats for lab-to-clinic translation of cell therapy for AD patients

There are some caveats that warrant additional studies to strengthen the rationale for clinical application of cell therapy for AD. The present study used the cholinotoxin model. With the advent of AD transgenic mice, testing the safety and efficacy of cell therapy in these humanized AD models may reveal a closer approximation the potential effects of the human NSCs with the human disease. Whereas the characterization of behavioral and histological outcomes of NSC transplantation was investigated up to 9 weeks post-transplantation, AD being a progressive neurological disorder may require more long-term studies to reveal stable functional recovery. Additionally, the translation of cell therapy to AD in general may benefit from the Stroke Treatment Academic Industry Roundtable or STAIR (Albers et al., 2001) and Stem cell Therapeutics as an Emerging Paradigm in Stroke or STEPS (Savitz et al., 2011) for further translational guidance of bringing experimental therapeutics from the laboratory to clinic, which may provide more stringent validation of outcome measures by employing multiple laboratory testing of cell therapy. Finally, co-morbidity factors, such as age and cerebrovascular events, which may exacerbate disease symptoms and therefore may not be responsive to cell therapy may need to be incorporated in testing cell therapy for AD to better reveal the stem cell safety and efficacy profiles.

Additionally, the identification of the most suitable donor cell type that can be transplanted for AD must be addressed before proceeding to the clinic. The most important of the safety issues is the risk of tumorigenesis through grafted stem cells. Various types of stem cells are able to differentiate into neurons, including not only NSCs but also ESCs, EGCs, bone marrow MSCs, umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cells, and even induced pluripotent cells generated from adult somatic cells. While initially the goal is to produce an ample supply of cells for transplantation, the eventual objective is for these cells following transplantation to switch off their proliferative capacity and commit toward neural lineage. Therefore it is important to find the cell best suited for therapy to decrease the risk of tumorigenesis. Since the presence of NSCs in adult CNS is known to exist within neurogenic and non-neurogenic sites, neurons and glial cells have been cultured from adult CNS tissue samples, further stirring the ethical debates on whether oocytes or embryonic or fetal materials should be used to generate stem cells, as stem cells can be isolated from adult tissues as well. Today, many laboratory studies are attempting to fully characterize the proliferative and differentiation ability of NSCs which will reveal their stemness property and therapeutic potential, respectively, in relation to embryonic or fetal stem cells. In the end, the demonstration of safety and efficacy profiles of stem cell therapy for AD will be pivotal for initiating clinical trials.

Conclusions

Previous studies demonstrate the benefits of NSCs as a cell source for transplant therapy for patients suffering from neurological disorders, including PD, HD, ALS, MS, stroke, and SCI. The recent study of Dr. Kim and colleagues (Park et al., 2012a) now shows that we may be closer to introducing genetically modified NSCs for transplant therapy in AD. However, there are serious caveats limiting the use of stem cells in the clinic. In particular, the long-term survival and phenotypic stability of stem cells following transplantation may not be favorable in that despite their highly purified cell population, stem cells may contain other neuronal or glial cell types that might produce unpredictable interactions among grafted cells or with host neurons, and this can decrease graft optimization. Tumorigenesis from small numbers of stem cells that escape differentiation and selection processes is a major cause for concern. In contrast, continuously dividing immortalized cell lines of human NSCs as generated by the introduction of oncogenes have advantageous features for cell replacement therapy and gene therapy. Human NSCs are homogeneous, as they are generated from a single clone. Therefore, they can be expanded to large numbers in vitro; and stable expression of therapeutic genes can be achieved easily and quickly. Immortalized human NSCs have emerged as a highly efficient source of cells for genetic manipulation and gene transfer into the CNS ex vivo. Following transplantation into damaged brain tissue, NSCs have a good survival and graft rate, and differentiate into both neurons and glial cells. By introducing relevant signal molecules or regulatory genes into the human stem cell line, it is now possible to obtain a large number of selected populations of neurons or glial cells from continuously growing human NSCs. There is a need for further studies in order to target the signals of differentiation and integration of NSCs, as well as determine the favorable conditions in order to increase the therapeutic benefits of NSCs in the AD brain.

Acknowledgments

The author extends gratitude to Mr. Nathan Weinbren and Ms. Loren E. Glover for their technical assistance in the final preparation of the manuscript and figure, respectively. CVB is supported by NIH NINDS R01 NS071956, DOD W81XWH-11-1-0634, and the James and Esther King Foundation for Biomedical Research Program 1KG01-33966, SanBio Inc., Celgene Cellular Therapeutics, KMPHC and NeuralStem Inc.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CD

cDNA

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- NGF

neural growth factor

- NSC

neural stem cell

- SCF

stem cell factor

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor-1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial cell growth factor

- VM

ventral mesencephalic

References

- Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Danks MK. Neural stem cell mediated tumor-selective gene delivery: towards high grade glioma clinical trials. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:S136. [Google Scholar]

- Albers GW, Goldstein LB, Hess DC, Wechsler LR, Furie KL, Gorelick PB, Hurn P, Liebeskind DS, Nogueira RG, Saver JL STAIR VII Consortium. Stroke Treatment Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) recommendations for maximizing the use of intravenous thrombolytics and expanding treatment options with intra-arterial and neuroprotective therapies. Stroke. 2001;42:2645–2650. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.618850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas E. Stem cells in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2002;57:795–808. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KR, Tzavara ET, Wu S, Wade MR, Bymaster FP, Paul SM, Nomikos GG. Cholinergic dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease is reversed by an anti-Aβ antibody. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:825–832. doi: 10.1172/JCI27120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartus R, Dean RL, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Valverde J, Alexi T, Poulsen K, Moffat B, Vandlen RA, Rosenthal A, Hefti F. Mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons protected by GDNF from axotomy-induced degeneration in the adult brain. Nature. 1995;373:339–341. doi: 10.1038/373339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund LM, Sanchez-Pernaute R, Chung S, Andersson T, Chen IY, Mc-Naught KS, Brownell AL, Jenkins BG, Wahlestedt C, Kim KS, Isacson O. Embryonic stem cells develop into functional dopaminergic neurons after transplantation in a Parkinson rat model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:2344–2349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022438099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blurton-Jones M, Kitazawa M, Martinez-Coria H, Castello NA, Müller FJ, Loring JF, Yamasaki TR, Poon WW, Green KN, LaFerla FM. Neural stem cells improve cognition via BDNF in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:13594–13599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901402106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlongan CV. Transplantation therapy for Parkinson's disease. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2000;9:2319–2330. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.10.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlongan CV, Sanberg PR. Neural transplantation for treatment of Parkinson's disease. Drug Discov. Today. 2002;15:674–682. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlongan CV, Sanberg PR, Freeman TB. Neural transplantation for neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet. 1999;353:SI29–SI30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)90229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Alzheimer's disease: a disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science. 1983;219:1184–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.6338589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerich DF, Winn SR, Harper J, Hammang JP, Baetge EE, Kordower JH. Implants of polymer-encapsulated human NGF-secreting cells in the non-human primate: rescue and sprouting of degenerating cholinergic basal forebrain neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;349:148–164. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris W, Mansourian S, Chang Y, Lindsley L, Eckman EA, Frosch MP, Eckman CB, Tanzi RE, Selkoe DJ, Guenette S. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta protein and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:4162–4167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W, Wictorin K, Björklund A, Williams LR, Varon S, Gage FH. Amelioration of cholinergic neuron atrophy and spatial memory impairment in aged rats by nerve growth factor. Nature. 1987;329:65–68. doi: 10.1038/329065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flax JD, Aurora S, Yang C, Simonin C, Wills AM, Billinghurst LL, Jendoubi M, Sidman RL, Wolfe JH, Kim SU, Snyder EY. Engraftable human neural stem cells respond to developmental cues, replace neurons and express foreign genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:1033–1039. doi: 10.1038/3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank RT, Edmiston M, Kendall SE, Najbauer J, Cheung CW, Kassa T, Metz MZ, Kim SU, Glackin CA, Wu AM, Yazaki PJ, Aboody KS. Neural stem cells as a novel platform for tumor-specific delivery of therapeutic antibodies. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed CR. Will embryonic stem cells be a useful source of dopamine neurons for transplant into patients with Parkinson's disease? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:1755–1757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062039699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman TB, Olanow CW, Hauser RA, Nauert GM, Smith DA, Borlongan CV, Sanberg PR, Holt DA, Kordower JH, Vingerhoets FJ, Snow BJ, Caine D, Gauger LL. Bilateral fetal nigral transplantation into the postcommissural putamen in Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1995;38:379–388. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman S. Stem and progenitor cell-based therapy of the human central nervous system. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:862–871. doi: 10.1038/nbt1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutova M, Najbauer J, Chen MY, Potter PM, Kim SU, Aboody KS. Therapeutic targeting of melanoma cells using neural stem cells expressing carboxylesterase, a CPT-11 activating enzyme. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2010;5:273–276. doi: 10.2174/157488810791824421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutova M, Shackleford GM, Khankaldyyan V, Herrmann KA, Shi XH, Mittelholtz K, Abramyants Y, Blanchard MS, Kim SU, Annala AJ, Najbauer J, Synold TW, D'Apuzzo M, Barish ME, Moats RA, Aboody KS. Neural stem cellmediated CE/CPT-11 enzyme/prodrug therapy in transgenic mouse model of intracerebellar medulloblastoma. Gene Ther. 2012 doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.12. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefti F. NGF promotes survival of septal cholinergic neurons after fimbrial transection. J. Neurosci. 1986;6:2155–2161. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-08-02155.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemming ML, Patterson M, Reske-Nielsen C, Lin L, Isacson O, Selkoe DJ. Reducing amyloid plaque burden via ex vivo gene delivery of an Aβ-degrading protease: a novel therapeutic approach to Alzheimer disease. PLoS Med. 2007;4:1405–1416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DH, Lee HJ, Park IH, Seok JI, Kim BG, Joo IS, Kim SU. Intrathecal transplantation of human neural stem cells overexpressing VEGF provides behavioral improvement, disease onset delay and survival extension in transgenic ALS mice. Gene Ther. 2009;16:1034–1044. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Shirotani K, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Hama E, Lee HJ, Saido TC. Metabolic regulation of brain Aβ by neprilysin. Science. 2001;292:1550–1562. doi: 10.1126/science.1059946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG, Hida H, Nakahira K, Ikenaka K, Kim HJ, Nishino H. Pleiotrophin mRNA is highly expressed in neural stem (progenitor) cells of mouse ventral mesencephalon and the product promotes production of dopaminergic neurons from embryonic stem cell-derived nestinpositive cells. FASEB J. 2004;18:1237–1239. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0927fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang UJ, Fisher LJ, Joh TH, O'Malley KL, Gage FH. Regulation of dopamine production by genetically modified primary fibroblasts. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:5203–5211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05203.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SU. Human neural stem cells genetically modified for brain repair in neurological disorders. Neuropathology. 2004;24:159–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2004.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SU, de Vellis J. Stem cell-based cell therapy in neurological diseases: a review. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:2183–2200. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower JH, Freeman TB, Snow BJ, Vingerhoets FJ, Mufson EJ, Sanberg PR, Hauser RA, Smith DA, Nauert GM, Perl DP, Olanow CW. Neuropathological evidence of graft survival and striatal reinnervation after the transplantation of fetal mesencephalic tissue in a patient with Parkinson's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1118–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston JW. The promise of stem cells in Parkinson disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:23–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI24012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Kim KS, Kim EJ, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells over-expressing VEGF provide neuroprotection, angiogenesis and functional recovery in mouse stroke model. PLoS One. 2007;1:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ST, Chu K, Jung KH, Kim SJ, Kim DH, Kang KM, Hong NH, Kim JH, Ban JJ, Park HK, Kim SU, Park CG, Lee SK, Kim M, Roh JK. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of intravascular neural stem cell transplantation in hemorrhagic stroke. Brain. 2008;131:616–629. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Kim MK, Kim HJ, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells genetically modified to overexpress Akt1 provide neuroprotection and functional improvement in mouse stroke model. PLoS One. 2009a;4:e5586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Kim HJ, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells overexpressing glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) promote functional recovery and neuroprotection in experimental cerebral hemorrhage. Gene Ther. 2009b;16:1066–1076. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Lim IJ, Lee MC, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells genetically modified to overexpress BDNF promote functional recovery and neuroprotection in mouse stroke model. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010;88:3282–3294. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Lim IJ, Park SW, Ko YB, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells genetically modified to express human nerve growth factor (NGF) gene restore cognition in mouse with ibotenic acid-induced cognitive dysfunction. Cell Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.3727/096368912X638964. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Bjorklund A. Cell therapy in Parkinson's disease. NeuroRx. 2004;1:382–393. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.4.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Kokaia Z. Stem cells for the treatment of neurological disorders. Nature. 2006;441:1094–1096. doi: 10.1038/nature04960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Rehncrona S, Gustavii B, Brundin P, Astedt B, Widner H, Lindholm T, Bjorklund A, Leenders KL, Rothwell JC, Frackowiak R, Marsden CD, Johnels B, Steg G, Freedman R, Hoffer BJ, Seiger A, Strömberg I, Bygdeman M, Olson L. Fetal dopamine-rich mesencephalic grafts in Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 1988;2:1483–1484. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90950-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Widner H, Rehncrona S, Brundin P, Odin P, Gustavii B, Frackowiak R, Leenders KL, Sawle G, Rothwell JC, Bjöurklund A, Marsden CD. Transplantation of fetal dopamine neurons in Parkinson's disease: one-year clinical and neurophysiological observations in two patients with putaminal implants. Ann. Neurol. 1992;31:155–165. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrazo I, Leon V, Torres C, Aguilera MC, Varela G, Alvarez F, Fraga A, Drucker-Colin R, Ostrosky F, Skurovich M, Franco R. Transplantation of fetal substantia nigra and adrenal medulla to the caudate nucleus in two patients with Parkinson's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;318:51. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801073180115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr RA, Rockenstein E, Mukherjee A, Kindy MS, Hersh LB, Gage FH, Verma IM, Masliah E. Neprilysin gene transfer reduces human amyloid pathology in transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1992–1996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-01992.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchor JP, Pawlak R, Strickland S. The tissue plasminogen activatorplasminogen proteolytic cascade accelerates amyloid-beta degradation and inhibits Aβ-induced neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:8867–8871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08867.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC, Eckman EA, Sambamurti K, Dobbs N, Chow KM, Eckman CB, Hersh LB, Thiele DL. Amyloid-beta peptide levels in brain are inversely correlated with insulysin activity levels in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:6221–6226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031520100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Steiner S, Zhou Y, Arai H, Roberson ED, Sun B, Chen J, Wang X, Yu G, Esposito L, Mucke L, Gan L. Antiamyloidogenic and neuroprotective functions of cathepsin B: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2006;51:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Lee HJ, Joo SS, Bae DK, Yang G, Yang YH, Lim I, Matsuo A, Tooyama I, Kim YB, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells over-expressing choline acetyltransferase restore cognition in ratmodel of cognitive dysfunction. Exp. Neurol. 2012a;234:521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Joo SS, Kim TK, Lee SH, Kang H, Lee HJ, Lim I, Matsuo A, Tooyama I, Kim YB, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells overexpressing choline acetyltransferase restore cognitive function of kainic acid-induced learning and memory deficit animals. Cell Transplant. 2012b;21:365–371. doi: 10.3727/096368911X586765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafuse VF, Soundararajan P, Leopold C, Robertson HA. Neuroprotective properties of cultured neural progenitor cells are associated with the production of sonic hedgehog. Neuroscience. 2005;131:899–916. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz SI, Chopp M, Deans R, Carmichael ST, Phinney D, Wechsler L. Stem Cell Therapy as an Emerging Paradigm for Stroke (STEPS) II. Stroke. 2011;42:825–829. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäbitz WR, Sommer C, Zoder W, Kiessling M, Schwaninger M, Schwab S. Intravenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduces infarct size and counterregulates Bax and Bcl-2 expression after temporary focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2000;31:2212–2217. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NO, Przylecki W, Yang W, Ziu M, Teng Y, Kim SU, Black PM, Aboody KS, Carroll RS. Brain tumor tropism of transplanted human neural stem cells is induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. Neoplasia. 2005;7:623–629. doi: 10.1593/neo.04781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol HJ, Jin J, Seong DH, Joo KM, Kang W, Yang H, Kim J, Shin CS, Kim Y, Kim KH, Kong DS, Lee JI, Aboody KS, Lee HJ, Kim SU, Nam DH. Genetically engineered human neural stem cells with rabbit carboxyl esterase can target brain metastasis from breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2011;311:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimato S, Natsume A, Takeuchi H, Wakabayashi T, Fujii M, Ito M, Ito S, Park IH, Bang JH, Kim SU, Yoshida J. Human neural stem cells target and deliver therapeutic gene to experimental leptomeningeal medulloblastoma. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1132–1142. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder BJ, Olanow CW. Stem cell treatment for Parkinson's disease: an update for 2005. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2005;18:376–385. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000174298.27765.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag KC, Simantov R, Isacson O. Stem cells may reshape the prospect of Parkinson's disease therapy. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;134:34–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N, Seth K, Khanna VK, Ansari RW, Agrawal AK. Long-term functional restoration by neural progenitor cell transplantation in rat model of cognitive dysfunction: co-transplantation with olfactory ensheathing cells for neurotrophic factor support. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2009;27:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroemer P, Patel S, Hope A, Oliveira C, Pollock K, Sinden J. The neural stem cell line CTX0E03 promotes behavioral recovery and endogenous neurogenesis after experimental stroke in a dose-dependent fashion. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2009;23:895–909. doi: 10.1177/1545968309335978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi Y, Takahashi J, Saiki H, Morizane A, Hayashi T, Kishi Y, Fukuda H, Okamoto Y, Koyanagi M, Ideguchi M, Hayashi H, Imazato T, Kawasaki H, Suemori H, Omachi S, Iida H, Itoh N, Nakatsuji N, Sasai Y, Hashimoto N. Dopaminergic neurons generated from monkey embryonic stem cells function in a Parkinson primate model. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:102–109. doi: 10.1172/JCI21137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynski MH. Gene therapy for neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:51–57. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynski MH, U HS, Amaral DG, Gage FH. Nerve growth factor infusion in primate brain reduces lesion-induced cholinergic neuronal degeneration. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:3604–3614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03604.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynski MH, Thal L, Pay M, Salmon DP, U HS, Bakay R, Patel P, Blesch A, Vahlsing HL, Ho G, Tong G, Potkin SG, Fallon J, Hansen L, Mufson EJ, Kordower JH, Gall C, Conner J. A phase 1 clinical trial of nerve growth factor gene therapy for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med. 2005;11:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nm1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Clark AW, Coyle JT, DeLong MR. Alzheimer disease: evidence for selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis. Ann. Neurol. 1981;10:122–126. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Sasaki A, Yoshimoto R, Kawahara Y, Manabe T, Kataoka K, Asashima M, Yuge L. Neural stem cells improve learning and memory in rats with Alzheimer's disease. Pathobiology. 2008;75:186–194. doi: 10.1159/000124979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan AG, Long DH, Gu HG, Yang DD, Hong LP, Leng SL. BDNF improves the effects of neural stem cells on the rat model of Alzheimer's disease with unilateral lesion of fimbria-fornix. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;440:331–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara T, Matsukawa N, Hara K, Yu G, Xu L, Maki M, Kim SU, Borlongan CV. Transplantation of human neural stem cells exerts neuroprotection in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:12497–12511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3719-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara T, Matsukawa N, Hara K, Maki M, Ali MM, Yu SJ, Bae E, Yu G, Xu L, McGrogan M, Bankiewicz K, Case C, Borlongan CV. Notch-induced rat and human bone marrow stromal cell grafts reduce ischemic cell loss and ameliorate behavioral deficits in chronic stroke animals. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:1501–1514. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Najbauer J, Annala AJ, Garcia E, Metz MZ, Gutova M, Polewski MD, Gilchrist M, Glackin CA, Kim SU, Aboody KS. Human neural stem cell tropism to metastatic breast cancer. Stem Cells. 2012;30:314–325. doi: 10.1002/stem.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]