Abstract

Where people die has important implications for end-of-life (EOL) care. Assisted living (AL) increasingly is becoming a site of EOL care and a place where people die. AL residents are moving in older and sicker and with more complex care needs, yet AL remains largely a non-medical care setting that subscribes to a social rather than medical model of care. The aims of this paper are to add to the limited knowledge of how EOL is perceived, experienced, and managed in AL and to learn how individual, facility, and community factors influence these perceptions and experiences. Using qualitative methods and a grounded theory approach to study eight diverse AL settings, we present a preliminary model for how EOL care transitions are negotiated in AL that depicts the range of multilevel intersecting factors that shape EOL processes and events in AL. Facilities developed what we refer to as an EOL presence, which varied across and within settings depending on multiple influences, including, notably, the dying trajectories and care arrangements of residents at EOL, the prevalence of death and dying in a facility, and the attitudes and responses of individuals and facilities towards EOL processes and events, including how deaths were communicated and formally acknowledged and the impact of death and dying on residents and staff. Our findings indicate that in the majority of cases, EOL care must be supported by collaborative arrangements of care partners and that hospice care is a critical component.

Introduction

Where people die has important implications for end-of-life (EOL) care and experiences (Ball et al., 2004; Lynn, 2002). Assisted living (AL), the fastest growing long-term care option in the U.S. and home to more than one million U.S. older adults (Mollica, Houser, & Ujvari, 2010; Metlife Mature Market Institute, 2011), increasingly is becoming a site of EOL care and a place where people die (Golant, 2004; Munn, Hanson, Zimmerman, Sloane, & Mitchell, 2006). From 14–33% of residents die in AL each year (Golant, 2004; Munn et al., 2006; Zimmerman, et al., 2005); nearly half of those in dementia care units (DCUs) remain until death (Hyde, Perez, & Reed, 2008). Additionally, aging (i.e., dying) in place is a main tenet of AL philosophy (Hyde, et al., 2008), and most residents consider AL their final home (Ball et al., 2004). National data over recent decades indicate an increase in resident length of stay. Data from 1995 report an average tenure of AL residents of 18 months (Hawes, Rose, & Phillips, 1999), whereas 2010 data report a median tenure of 22 months (Caffrey et al., 2012).

Accompanying the growing prevalence of death is the increased frailty of AL residents. Data from a 2010 national survey of AL facilities with four or more beds show that residents are entering older and sicker and with greater care needs (Caffrey et al., 2012). The average age at AL admission is 85, and 54% of residents are 85 and older. The typical resident requires assistance with more than one activity of daily living (ADL); more than a third need help with at least three. These data also show the growing presence of comorbidity. Half of residents have from two to three chronic conditions; 26% have from four to ten. Although this survey found that 42% of residents had Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, earlier estimates indicate a prevalence of dementia ranging from nearly half (Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Kemp, 2010) to 67.7% (Leroi et al., 2006).

Despite evidence of increasing resident impairment and death, AL remains largely a non-medical care setting that ideally subscribes to a social rather than medical model of care (Golant, 2008), although little data exist as to how many facilities practice this model. The bulk of care is provided by low-wage unlicensed workers with little, if any, training in EOL care (Ball et al., 2010; Stone, 2010). In most states, AL staff are not permitted to provide skilled health care, although more and more AL facilities have licensed nurses on staff. Increasingly, however, states, including Georgia (the site of this study), are making statutory, regulatory, and policy changes that expand levels of AL care (Mollica et al., 2010), thus enhancing AL’s ability to accommodate increasing resident frailty and EOL care.

Also relevant to EOL is the expansion of hospice use in AL, principally owing to Medicare and Medicaid benefits but also due to regional market forces and state policies (Mollica et al., 2010). Facility and individual factors that influence hospice use in AL include staff knowledge and attitudes (Cartwright & Kayser-Jones, 2003; Cartwright, Miller, & Volpin, 2009; Dobbs, Hanson, Zimmerman, Williams, & Munn, 2006), point of physician referral (Smith, Seplaki, Biagtan, DuPreez, & Cleary, 2008), and residents’ clinical conditions and AL tenure (Dobbs, et al., 2006). Evidence exists that hospice services positively affect EOL in AL through improved pain control and higher levels of ADL care (Munn et al., 2006) and greater family satisfaction (Cartwright et al., 2009). Other research found that AL staff view hospice as an important source of training and bereavement services, whereas residents indicated that hospice increases their understanding of death and families value hospice’s monitoring role (Munn et al., 2008). Another study found that administrator support for dying in place with hospice, integration of hospice services into facility care practices, and resident-staff relationships were key factors affecting hospice outcomes (Cartwright et al., 2009).

Informal care from families and friends contributes a significant care component in AL (Ball et al., 2004; Ball et al., 2005; Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013; Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2013; Williams, Zimmerman, & Williams, 2012). Informal caregivers typically provide socio-emotional support and help with various instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as money management, shopping, and transportation to medical appointments, more so than help with ADLs (Ball et al., 2005; Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2013), although spouses living together in AL also provide ADL support (Kemp, 2008, 2012). Our recent research suggests that most AL residents have care convoys that include family and friends in addition to formal caregivers and that adapt to changes in residents’ care needs and transitions in informal and formal care networks (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013).

EOL as a Social Process

Early ethnographic studies on EOL in nursing homes (Gubrium, 1975; Marshall, 1975a,b; Savishinsky, 1991) and hospitals (Glaser & Strauss, 1965, 1968) point to the usefulness of an interpretive lens when examining EOL. As Marshall (1975a: 355) notes, dying is a “social event” that takes place in a social context. Individuals’ experiences while dying, thus, are differently shaped by the nature of their illness and others’ reactions to it, by the care provided for their physical, emotional, social, psychological, and spiritual needs, and by the social and physical environments in which they receive care. Likewise, in AL death and dying influence the surrounding social and physical environments and affect others in the setting, whether approaching death or not.

Glaser and Strauss (1968) in their classic treatise on death and dying in hospitals (1968: 6) refer to the socially defined course of dying as a dying trajectory. Dying trajectories have both duration (the length of the dying course) and shape (the slope of individuals’ decline as they approach death). Dying can be sudden or span days, months, or years. Dying statuses and trajectories are not purely objective, but also perceived (Bern-Klug, 2009; Glaser & Strauss, 1968; Marshall, 1975a). Consequently, stakeholders (i.e., residents, families, friends, AL administrators and workers) may not share perceptions of an individual’s dying status or trajectory, or how best to manage EOL care. Bern-Klug (2009), in considering social interactions at EOL, points out the ongoing challenge of determining when an individual is in fact at EOL. Consistent with the Institute of Medicine (2003), we define EOL broadly to include periods of decline associated with advanced age or chronic illness where the timing of death is uncertain.

Notwithstanding AL’s changing care landscape, AL largely has been overlooked by researchers studying EOL (Gruneir, Weitzen, Truchil, Teno, & Roy, 2007). Existing research consists primarily of comparisons to nursing home care (Sloane, Zimmerman, Hanson, Mitchell, Riedel-Leo, & Custis-Buie, 2003), small qualitative case studies (Rubenstein, 2001; Sanders & Anewalt, 2010), administrator attitudes towards hospice (Cartwright & Kayser-Jones, 2003), and outcomes of hospice use (Munn et al., 2006, 2008). Little is known about the experiences of those dying, how EOL affects a home’s social environment, or the way EOL is managed and negotiated among key stakeholders in AL. This article addresses these knowledge gaps. Our specific aims are to: 1) increase understanding of how EOL is perceived, experienced, and managed in AL; and 2) learn how individual, facility, and community factors influence these perceptions, experiences, and processes.

Design and Methods

Data for this analysis derive from a 3-year (2008–2011) externally-funded mixed methods study, “Negotiating Residents’ Relationships in AL: The Experience of Residents” (PI, Mary M. Ball). The study’s overall aim was to learn how to create an environment that maximizes residents’ ability to negotiate and manage relationships with other residents. We purposely selected eight AL sites in urban and suburban areas of metropolitan Atlanta for in-depth study, seeking variation in ownership, size, fee level, location, and resident profile. A ninth home was added to increase the number of quantitative surveys, but this analysis utilizes qualitative data collected from the initial eight sites. Tables 1 and 2 describe select site characteristics and resident profiles. Although four of the homes had DCUs, we collected data only in AL sections. The project was approved by the Georgia State University Institutional Review Board. For purposes of anonymity, we use pseudonyms for AL settings and participants.

Table 1.

Select Facility Characteristics

| Home | Mean Census/Capacity | Ownership | Mo. Fee Range | Location | DCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meadowvale | 52/66 | Corporate | $2,100 – $4,800 | Suburban | Yes |

| Peachtree Hills | 49/75 | Private | $2,645 – $3,145 | Urban | No |

| Caroline Place | 33/42 | Corporate | $2,700 – $3,990 | Urban | No |

| Feld House | 22/47 | Foundation | $2,700 – $4,300 | Suburban | No |

| The Highlands | 78/100 | Corporate | $2800–$3500 | Suburban | Yes |

| Garden House | 16/18 | Private | $2550–$2900 | Suburban | Yes |

| Pineview | 66/68 | Corporate | $2,985–$4,195 | Small Town | No |

| Oakridge | 42/55 | Corporate | $2,700 – $5,295 | Urban | Yes |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Facility Resident Profiles

| Home | Race/Culture | Age Range | % Dementia | % Wheel Chairs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meadowvale | Most White | 42–100 | 45 | 31 |

| Peachtree Hills | Most White | 65–97 | 39 | 34 |

| Caroline Place | Most White | 59–100 | 54 | 24 |

| Feld House | All White/ 99% Jewish | 52–99 | 44 | 39 |

| The Highlands | Most White | 78–98 | 14 | 10 |

| Garden House | Most White | 65–96 | 24 | 0 |

| Pineview | Most White | 73–98 | 20 | 36 |

| Oakridge | All African American | 54–102 | 34 | 22 |

Data Collection

Teams of trained sociology and gerontology graduate researchers led by the study’s key investigators collected data for a one-year period in each home using in-depth and informal interviews and participant observation. The number of researchers, interviews, and visits per site depended on facility census (see Table 3). We interviewed the administrator in each home, as well as selected activity and care staff. These interviews addressed job roles and responsibilities, residents’ social relationships, and relevant facility policies and practices, including admission and discharge criteria and staffing. We selected resident participants purposely for variation in gender, functional status, marital and family status, facility tenure, race, ethnicity, and age. Resident interviews inquired about AL life and social relationships, including the nature of co-resident relationships and perceptions of how various resident and facility factors, counting death and decline, affect relationships. All in-depth interviews were conducted in-person and digitally recorded and transcribed. Observations and informal interviews were documented in detailed field notes. We used NVivo 10.0, a software package for qualitative data management, to assist with data management, storage, and analysis.

Table 3.

Data Collection by Home

| Home | Administrator Interviews | Resident Interviews | Resident Surveys | Staff Interviews | Visits | Observation Hours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meadowvale | 1 | 4 | 22 | 2 | 126 | 397 |

| Peachtree Hills | 1 | 6 | 26 | 3 | 125 | 379 |

| Caroline Place | 1 | 4 | 17 | 2 | 153 | 485 |

| Feld House | 1 | 5 | 19 | 3 | 131 | 396 |

| The Highlands | 1 | 7 | 39 | 3 | 197 | 580 |

| Garden House | 1 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 47 | 154 |

| Pineview | 1 | 13 | 28 | 5 | 210 | 621 |

| Oakridge | 1 | 9 | 19 | 5 | 178 | 578 |

| Total | 8 | 51 | 178 | 24 | 1167 | 3590 |

Data Analysis

Our qualitative analysis was informed by principles of grounded theory method (GTM)–an approach used to understand and develop theory about social processes (Charmaz, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). GTM is a constant comparative method of inquiry, with data collection, hypothesis generation, and analysis occurring simultaneously, that involves a three-stage coding process (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Our research team collaborated to develop and refine coding categories throughout data collection.

Coding procedures followed Strauss & Corbin (1998). In initial coding, we used line by line, or open coding, to examine data for emergent themes or concepts based on questions asked by the investigators and issues raised by informants. For example, the code “care arrangements” was developed to capture the types of care and caregivers utilized by residents approaching death. Words or phrases indicating, for example, the type of formal caregivers (AL staff, hospice worker etc.) who provide care, when, and how often were identified and a descriptive code applied to this text (“formal care component”). Other codes (e.g., ADL care) reflect care process. As new themes emerged, codes were modified, collapsed, or dropped. Next, in axial coding we linked categories and made connections between the data indicating relationships, conditions, context, and consequences. For example, certain community-level factors intersected with facility- and resident-level factors to shape the management of EOL care. We thus examined “care arrangements,” with respect to factors such as individuals’ clinical conditions and family support, facility staffing levels and policies regarding external care workers, and state AL regulations, and then related these categories to outcomes, such as “dying in AL” and “EOL presence.” In the final stage, “selective coding,” major categories were organized around our central explanatory concept or core category, “negotiating EOL care transitions in AL,” which is the process of working out EOL care arrangements amongst residents and their formal and informal caregivers over time in response to an array of multilevel, interactive factors. Analysis was complete when theoretical saturation (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) occurred, i.e., when no new data emerged regarding a category, when category development was dense, and when relationships between categories were well established and validated by key investigators. We used several strategies to establish the credibility of our analysis, guide theory development, and help identify potential researcher bias, including: analytical memos, diagrams, and charts; regular research team meetings; negative case analysis; and member checking (i.e., soliciting feedback from participants regarding findings).

Findings

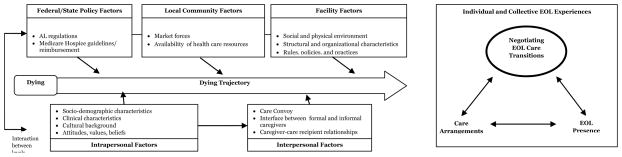

The figure depicts our conceptual model for how EOL care transitions are negotiated in AL. We use a social ecological framework to conceptualize the range of multilevel intersecting factors–at federal and state policy, local community, facility, and individual levels–that shape this process. This framework suggests that negotiating EOL care transitions, which we examine both collectively by facility and individually by resident, affects care arrangements, which together reflect back on and influence the AL environment, creating what we refer to as an EOL presence. By EOL presence we mean the existence in a setting’s social and physical environment of artifacts, people, processes, and events that serve as indicators of death and dying. Such indicators included hospital beds, increased presence of families or hospice personnel, removal of bodies, death notices, memorial services, and grief of loved ones. EOL presence varies across and within settings depending on these multiple influences, including, notably, the prevalence of and response to death, and in turn shapes EOL care negotiation and arrangements. Our analysis indicates that EOL care is negotiated among key stakeholders–chiefly residents, their formal and informal caregivers, facility administrators, and state AL regulators–in response to the multilevel, interactive factors depicted in the model and examined in the findings presented below.

Death Events

Overall in the eight study homes 71(15%) of the 485 residents died during the one-year data collection period in each home. Deaths ranged from 1% in the Garden House to 29% in Feld House. Residents who died were from 62–103 years, with an overall mean of 88; tenure ranged from two weeks to eight and a half years, with a mean of 21 months. Table 4 shows the number of residents (total for study period), distribution of deaths, and means and ranges for age and tenure of residents across sites. Included are residents who died in AL or within 30 days of transfer to another care setting (e.g., hospital, nursing home). In most cases, time in other settings was just days. Almost half (46%) of residents died in their AL apartments, 24% in a hospital, 13% in a hospice facility, 6% in a nursing home or rehabilitation facility, and one at a party in the community. Place of death was unknown for 10% of residents.

Table 4.

Resident Deaths

| Home | # Residents | Resident Deaths N/% |

Age (yrs.) Range/ Mean |

Tenure (mos.) Range/ Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meadowvale | 62 | 6 / 10% | 83–92 / 87 | 1–66 / 25 |

| Peachtree Hills | 80 | 17 / 21% | 72–103 / 90 | 1–99 / 90 |

| Caroline Place | 50 | 7 / 14% | 62–99 / 85 | 3–34 / 24 |

| Feld House | 41 | 12 / 29% | 71–94 / 88 | 2–55 / 14 |

| The Highlands | 83 | 10 / 12% | 81–97 / 87 | 8–36 / 25 |

| Garden House | 21 | 1 / 4% | 82 | 3 |

| Pineview | 83 | 13 / 16% | 81–97 / 87 | 1–58 / 24 |

| Oakridge | 65 | 5 / 8% | 76–98 / 85 | <1–103 / 29 |

| Total | 485 | 71 / 15% | 62–97 / 91 | <1–103 /21 |

Dying Trajectories

We identified three dying trajectories (Glaser & Strauss, 1968) among residents based on duration and slope: 1) gradual decline associated with advanced age and chronic illness (61%); 2) steeper decline related to a terminal illness, typically cancer (14%); and 3) sudden death resulting from an acute health episode (25%).

The first and most common trajectory is illustrated by Barbara, aged 81, a five-year resident of Pineview. When we met Barbara, she used a wheelchair and was experiencing regular health crises related to life-long diabetes. Barbara began receiving hospice services with the onset of renal failure and died five months later in her apartment. Barbara’s dying trajectory simply represented a continuation of the decline she experienced in AL prior to assuming the dying status. A few residents in this category had short AL tenures, moving in after considerable decline. For example, Nathan, already on hospice when he moved to The Highlands at age 102, died less than a month later.

Beatrice, another Pineview resident, represents the second trajectory, with a compressed decline period. Prior to diagnosis of lung cancer at age 83, Beatrice, along with her husband, was active at Pineview and in the community. After five months of chemotherapy, Beatrice’s physician enrolled her in hospice and she died five months later in her AL apartment. Another example is Janice, who at age 71 moved to Feld House with stage-IV lung cancer and died after nine months, spending her last month in bed, with hospice only for her final days.

Typically, sudden deaths resulted from acute illness, sometimes related to falls. These included 83-year-old Albert, who died of a heart attack in his room at Meadowvale, and George, age 97, who fell at Pineview, breaking his hip, and died one week later in the hospital from pneumonia. Although those who died suddenly had one or more chronic conditions and some were quite frail, death was unexpected. George had significant vision and hearing impairment, emphysema, and mild dementia but, according to his daughter, expected to “live to be 100,” and had not been defined as dying.

As the examples above suggest (and as depicted in our model) residents’ dying trajectories, similar to their care transition negotiations, care arrangements, and, ultimately, ability to die in AL, occur in context of multiple, multilevel and interactive factors. Principal among these are residents’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, their attitudes, beliefs, and values, and their resources for informal and formal support, all of which can affect the point that dying is socially designated and when in the dying trajectory a resident enters AL. Key facility factors include policies related to admission, discharge, staff qualifications and staffing levels, and use of hospice and other external care workers. Dying trajectories and EOL experiences in AL are further influenced by local AL and hospice market forces, AL regulations, and Medicare rules for hospice reimbursement and care. The examination below of residents’ EOL care arrangements further illustrates the interaction of multilevel factors.

Care Arrangements

Residents varied in the type and extent of their EOL care needs and arrangements prior to death. By care we mean assistance with ADLs, such as bathing dressing, and toileting, and skilled care tasks, like medication and pain management, blood sugar monitoring, and catheter care. IADL tasks (most often carried out by family members) and emotional support (typically provided by a range of care convoy members, including co-residents) although important and meaningful (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013; Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2013) are not our focus here. Care arrangements denote the configuration of caregivers, or care convoys, who carried out necessary tasks. For 42% of residents, only AL staff provided care. The majority of residents had EOL care from additional sources: 38% from hospice; 15% from family members; and 10% from private care aides. Thirteen percent had at least three types of caregivers simultaneously. Data for some residents show fluctuations in care arrangements in response to changing conditions and needs. A minority of residents (7%), all who died suddenly and unexpectedly, had no apparent ADL or skilled care needs prior to death.

AL Staff

EOL care from AL direct care staff ranged from assistance with only bathing and dressing to help with all ADLs, including eating. Each of the study homes had either an RN or LPN on staff during day time hours. Their roles primarily entailed oversight of resident care and management of direct care workers. A facility’s ability to manage a resident’s care successfully depended on numerous factors, including: the resident’s needs, dying trajectory, and support resources; the facility’s resident profile, staff capacity, and admission and discharge policies; and the AL regulatory context. For example, prior to falling and breaking his hip, George was on oxygen, had significant hearing impairment, used a walker, and needed help with bathing, dressing, toileting, and grooming. Each AL building at Pineview averaged 34 residents with two caregivers per shift and a full-time housekeeper. Almost half of residents in George’s building used wheelchairs and required significant ADL help; six were discharged during the study to a nursing home because of increased care needs. George died in the hospital, but had he survived, his return to Pineview was dependent on his potential rehabilitation and on his daughter’s ability to negotiate, and possibly supplement, his care arrangements. Pineview, where 16% of residents died during the study year, tended to operate at or near capacity, owing in part to its ability to acquire AL residents from its adjoining independent residence and location in a small town with limited AL facilities, factors contributing to more stringent discharge policies that adhered strictly to state AL regulations. The Director at Pineview provided the following example of a situation that would lead to discharge:

…if they became total care, had a fall and required say a two person team to transfer. We only have two staff persons on at any one time so we really can’t tie up two staff people with one person because if there was an emergency or something else. So we don’t keep people that require a two person transfer.

In contrast, 29% of residents died in place at Feld House, which operated significantly under capacity and was located in an AL-rich suburb. Feld House, a private, non-profit home tended to staff above the state’s minimum requirement of one staff person per 15 residents in the day time and 25 at night. The Director voiced their more favorable retention policy:

If we already have a resident and he or she becomes very incapacitated, if we can handle them, I keep them. I do not want to throw somebody out at the end of their lives. I want them to be able to stay in their own home for as long as possible. And most do.

Hospice Care

The 27 residents (38%) who received hospice services on site included the large majority of residents who died in their AL apartments; seven residents utilized in-patient hospice. The duration of hospice ranged from just days to five months. A minority of these residents also had ADL help from family members (6) and paid aides (5). Hospice use depended on various factors, including residents’ clinical conditions and care needs, convoy members’ (i.e., residents, families, AL staff, and physicians) knowledge of and attitudes toward hospice, a facility’s relationship with hospice providers, and Medicare’s hospice reimbursement guidelines. In general, all residents who utilized hospice and died in AL required a higher level of care than their respective facilities had the capacity to provide and was permitted by state AL regulations; in most cases facilities had at least applied for a waiver from the state regulatory agency to retain these residents and arrange for the needed care. All residents with terminal cancer were enrolled in hospice, but for varying time periods–for example, Janice at Feld House, for her final days compared to five months for Beatrice at Pineview. Residents with other clinical conditions, often long-term and multiple, also benefited from hospice. Mable, age 90 and a two-year resident of Pineview, was already in a wheelchair and had heart disease and COPD when enrolled after a hospitalization, at which point she largely was confined to her hospital bed and cared for by AL and hospice staff, and occasionally her daughter, until her death two months later.

For these residents, hospice services facilitated dying in place, primarily because of the additional ADL care and provision of skilled nursing care, including administration and oversight of medications, pain management, and skin integrity, and supportive equipment, such as hospital beds, wheelchairs, and oxygen concentrators. Although the hospice care aides visited no more than tri-weekly, the supplemental ADL care they provided lessoned the workload of facility care staff and gave residents extra attention.

Facility nursing staff were not typically present at night and are not allowed by state law to provide skilled nursing care. Hospice RNs were available at all times for consultation or in medical emergencies, in addition to making weekly visits. AL staff and family members welcomed the additional oversight from hospice RNs. The daughter of Janice at Feld House regularly communicated with the hospice RN while her mother was dying and field notes indicate the positive outcomes hospice had for her and her mother:

Looking back, Joyce wishes she had put Janice under hospice care from the beginning because it changed the whole emphasis of her illness. She said hospice has been wonderful and have assured her they will keep Janice comfortable.

Moreover, administrators in each of the eight facilities confirmed hospice benefits. The Director at Peachtree Hills, where 10 of the 17 residents who died utilized hospice, said:

Oh yeah, we promote hospice. I think that if somebody is able to—I don’t know if the terminology is right but—die in place, that it’s much kinder than dying in a hospital or a nursing home, where it’s so institutional, where there’s not the love and care and friendliness. … And sometimes the level of care is beyond what we can do. So if they bring hospice in, then they can come back [from hospital or other skilled care facility] and they can stay here until they’re gone. We encourage anybody that’s gotten a diagnosis like that. We feel like when they’re RNs they are trained to see what we’re not and that the resident is getting a higher level of care but able to stay in place.

The Director of Caroline Place, where five of the seven residents who died received hospice care, expressed equal enthusiasm for the role of hospice:

Hospice, when they come in our building, it relieves us of a lot of things. … It’s almost like if somebody goes on hospice, they are then responsible for that resident. We still feed them and clean up after them and do those things, and what I mean by clean up after them is housekeeping and laundry.

Although our data indicate that hospice involvement relieved AL staff burden, we also found evidence that hospice workers communicated with AL staff about joint care of residents. The following field notes from illustrate such collaboration:

As I was about to leave the facility, I saw Mable’s hospice nurse talking to Karen and another staff person in the nurses’ station. I heard her say that she had ordered Mable a floating mattress and that the staff really needed to make sure that Mable kept off her heel because there is a sore on it. They also discussed the fact that Mable was dehydrated and that every time someone goes into the room they should try to get Mable to drink some fluids.

Although hospice care supported dying in place, it also increased the visibility of dying and thus EOL presence. For example, other residents were aware of hospice personnel in the building, and sometimes dying residents could be seen and heard in their rooms, as noted in field notes from The Highlands:

By the first of June 2010 Stephen was known to be a hospice recipient. At mid-month in June he was observed through his open apartment door to be sleeping very quietly on his back in a hospital bed in the middle of his living room.

Field note excerpts from Pineview depict the visibility of Mable’s final days:

I sat in the back corner, near Mable’s room. I suddenly heard her screaming for help, hollering and moaning, “Help! Help! My legs!!” …. As we were playing [bingo], I could hear Mable yelling, “I want to go home.”

In one case, hospice services were not sufficient to enable dying in place. Amanda, age 98, who required total care, had lived at Meadowvale for 10 years before her discharge to a nursing home six months before death. Although on hospice, Amanda had no family support or paid care. Her discharge also was prompted by an administrator change at Meadowvale and a recent citation from state AL regulators for keeping residents beyond the facility’s care capacity.

Typically, enrollment in the hospice program confirmed a resident’s dying status, yet data show that denial of dying can delay or prevent hospice use. For example, Greg, a Pineview resident with chronic liver disease and a history of heart disease and stroke, resisted the dying designation despite being critically ill, continuing to talk of moving out of AL up until his final weeks. Only after admission to the ICU with kidney failure was Greg sent to inpatient hospice, where he died eight days later. Even then, Greg’s son, who had provided regular ADL care and continued to administer homeopathic medicine. Field notes from a visit in the hospice facility provide evidence of the son’s supported of Greg’s denial:

Later, Greg, Jr. said that he wanted to keep things “positive.” He said that he didn’t think his Dad really understood what type of facility he was at and probably thought it was just an extension of the hospital. He told me that he thought he would eventually tell his Dad what the facilities purpose was so that he could tell his father “goodbye.”

With earlier hospice enrollment, Greg might have avoided hospitalization and been better prepared for death.

Paid Care Aides

A small group (8%) of residents had the resources to hire care aides privately to enable dying in place. These aides provided varying amounts of ADL care and monitoring, working alongside AL staff, family members, and hospice workers. For example, Inez, age 98, received care from a private aide and Oakridge staff from our study’s start until her death four months later. Inez routinely was observed sleeping in her wheelchair in common areas with her aide by her side. Vera a 29-month resident of Caroline Place with significant dementia, shared round-the-clock aides with her husband. The aides, who provided the bulk of ADL care and oversight for at least 10 months prior to Vera’s death, were joined by hospice workers Vera’s final two months. In some cases, private aides were utilized closer to the end of life. Sadie at The Highlands, who was hospitalized as a result of a fall two months prior to dying, was able to return to her AL apartment her last three weeks with help from private aides.

Family Care

For 11 residents (15%), family members, including five children, five spouses, and one sibling, were involved in EOL care together with other caregivers. Spouses, four of whom lived with the dying person, provided the most extensive care. Most involved was Bill, who moved to The Highlands subsequent to his wife Dot’s admission to the DCU. Ultimately Bill moved Dot into his apartment, where, with help from hospice and AL staff, he cared for her until her death three months later. They had been married for 67 years. Bill described his care roles:

By the time I came here she was getting to the point to where somebody had to be helping her all the time, morning mostly, and I did most of that because she acted like she was a little more familiar with me than people who were coming and going trying to take care of her. … I just, I wanted to make sure she was treated right, with respect and that sort of thing. … I did everything I guess that was almost humanly possible to try to help in any way I could because I knew it was a final type thing and she deserved it.

Another example is Jack, a 91-year-old Caroline Place resident, who experienced a fall, along with significant physical and cognitive decline, six months before he died. Jack received care from AL and hospice staff, a daughter, and a private care aide his last month. Jack’s wife, Jewel, provided emotional support. Field notes three weeks before death illustrate:

When I visited the Walton’s later, Jack was lying in his hospital bed and Jewel was beside him in her wheelchair. Jack was in good spirits and seemed happy to see me. Their sitter, Lola, said that the Walton’s have a loving family and that Jewel raised her children well because they always come by to see their parents. Lola said that it sometimes makes her cry to see how loving the Walton’s are with one another. While I was visiting, the couple reached out and held each other’s hands several times.

Responses to Death

Activities following a resident’s death, including death communication and acknowledgement and the effect of death on a home’s social and physical environment and EOL presence, varied across individual situations and AL settings. The factors shaping these variable outcomes, depicted in the figure, are discussed below.

Communicating Death

Residents in all homes indicated that they wanted to know about resident deaths. Yet, deaths generally were not discussed openly or formally announced by administrators and staff. As one resident in Caroline Place said, “Even when somebody dies, nobody, nobody announces it. Just everybody whispers it, you know? And it’s not right, I don’t think. I think they should be honored for being a new resident or being, you know, died or what.” A resident in Garden House, located in a small town, expressed a similar view:

You find that it gets over the grapevine sometimes, because the staff’s not really supposed to talk about—that’s another one of the rules. They’re not supposed to come up here and tell them something has happened. Like if somebody dies and you’ve got a suspicion that something’s happened, you ask them, they’ll say, “I can’t talk about it.”… Well usually it gets out some kind of way because somebody can go snoop and they’ll find out and then they’ll tell it.

As these residents’ words suggest, a death typically was communicated by “word of mouth.” We heard similar words from facility staff. When asked how information about deaths was conveyed to residents, the Activity Director at Pineview replied: “I don’t think there’s any standard memo. It’s just sort of word of mouth, ‘Did you know that Mrs. so and so passed away?’” Word tended to travel faster in smaller homes, such as Garden House. In all homes, researchers were aware of only a few instances where a death was formally announced. One was Barbara, who had lived at Pineview for five years and was a favorite of residents and staff. Field notes from the day she died report this rare occurrence, which took place in the dining room:

Suddenly, a woman from the administrative office and Joan, the front desk girl, called everyone’s attention and the woman said, “We lost one of our beloved residents today, and Joan is going to sing a song in Barbara’s honor.” I found it very interesting that they did indeed make an announcement, despite the fact that Charlotte [care staff] said it wasn’t in their policy to do so.

At Caroline Place resident deaths sometimes were announced by the Activity Director. Often when a resident was a close friend of the deceased, a staff person or family member communicated the news privately.

The reluctance of staff to communicate death information openly and directly generally was accounted for in terms of protecting residents. A housekeeper at Pineview stated a common viewpoint:

They don’t go around broadcasting it to everybody in the building because if somebody comes up and asks, the CNAs might let them know or I might let them know, if they ask, but as far as just going out, trying to tell ‘em all details about what’s going on, we don’t do that because that’s not going to make them feel no better about being here and knowing one of their neighbors done just passed. So we don’t go out spreading that kind of word, that kind of way because we don’t want to get the other residents upset.

At Feld House and Oakridge, administrators went beyond simply not telling residents to intentional concealment. Although Oakridge’s director admitted to using deception to “try to minimize the excitement,” she advocated for greater openness:

When they do find out, ultimately they’re going to find out, we go into the activities room, we talk about, “As you all know, Ms. such and such went out [to ER], unfortunately we’re sorry to announce that she’s passed.” We put a letter on the thing [reception desk] saying “In Bereavement” and we reassure them, “We’re sending the family members flowers, we’re doing this.” So I think the more you talk about it, the better they deal with it. If it happens and there’s no level of communication and they just find out, I think they get in a deeper funk.”

Facility staff also invoked the (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines as a barrier to providing death information to residents. When asked how deaths were handled at The Highlands, the Director replied: “Unfortunately because of HIPAA, I can’t give out a lot of information to the residents and that frustrates the residents to no end because I can’t tell them how their neighbors are doing.”

Residents often learned about deaths in less direct ways, sometimes days or even weeks after the event. Informal avenues of communication included witnessing a 911 response or body removal, reading obituaries in the local paper, family members gathering in a resident’s room or common area, removal of the deceased’s possessions, presence of flowers in a common area, and a vacant chair in the dining room. Field notes from Feld House, where almost a third of residents died during the study period, document a common form of communication in that home:

I talked to Hattie, who was reading the paper. She gasped and said, “Oh no, Joan died.” Hattie reads the obits every day and said she knew it was “their Joan” when she saw the reference to Feld House. She was shocked and had a number of questions for the staff. I told Reagan [a staff person] what Hattie had seen in the paper and she immediately said, “We were not going to tell the residents today but I guess John [resident] will also read it too and he will tell everyone.”

John, a habitual obituary reader, was known as a messenger of death information.

Before Barbara’s death was announced at Pineview, some residents learned the news through more subtle cues in the environment, as chronicled in field notes:

Louise [a resident] told me that Barbara died yesterday around 8:15. Louise said she was at breakfast and saw Barbara’s niece walk out of Barbara’s door crying. A few minutes later, the staff came to Barbara’s room. A little later, Barbara’s body was removed from the building. Louise told the story as a matter of fact.

A facility’s size and design impacted the visibility of such environmental cues. At Pineview all resident rooms surrounded common areas, increasing the conspicuousness of coming and going. At Garden House, the smallest home, deaths also were hard to conceal, as noted by the Director, when asked how residents learned of deaths: “Most of the time, if they are here, you know, they’re gonna know immediately because of the ambulance coming or whatever.” In larger homes with multiple floors, it was easier for deaths to go unnoticed. Other factors affecting awareness of death events included residents’ dying trajectories and fellow residents’ own cognitive and physical states. A Meadowvale resident reported how she and her husband, alert and active, learned of Albert’s sudden death:

It was Saturday because James and I were sitting in the front lobby and we noticed, I mean when we got down there the paramedic truck was already out there. James got up and said, “My goodness two fire trucks.” And I said, “Why in the world would they need all that?” We didn’t know who it was. Of course James being a minister always likes to know who it is. And we were sitting there and all of a sudden Sandra, the med tech, came flying out and said, “I can’t even get a pulse. I can’t even get a pulse, Mr. Hamilton.” And they were all crying, and a couple of the other staff members were around Sandra.

Formal Acknowledgement

Deaths were acknowledged formally in various ways, more in some homes and for only some residents in any one home. Sometimes the formal acknowledgement was the initial avenue of communication. At Oakridge and Meadowvale, framed announcements were placed on the reception desk for the majority of, but not all, residents who died. The typical practice at Peachtree Hills, was to place a rose and a card for residents to sign outside the dining room. This remembrance, instituted by residents in the independent section, was observed only for a few AL residents. In three homes, obituaries were posted in public places for certain residents who died. Memorial services were held in half of the homes. These services were well attended by residents, and sometimes residents spoke about a fellow resident who had passed away. Although sanctioned and facilitated by all homes, the responsibility for memorial services rested on families. The Activity Director at Caroline Place, a staff person with uncharacteristic openness regarding AL deaths, commented on the importance of resident participation in services:

So when a resident passes away, I don’t try to keep it a secret. I openly tell them “Mrs. Sandra Wiley has passed away and she has left us.” That’s why I am so grateful for the families that not only have an outside burial but they allow us to do a memorial. That means so much to them [residents], so much, then the ones that may have been the next-door neighbor or the one that ate lunch with them, to give them a chance to share their relationship or their feelings about the person. It helps. It goes such a long way.

At Peachtree Hills, a hospice agency arranged annual services to remember all the residents who passed away the previous year.

Three homes, Caroline Place, The Highlands, and Garden House, provided transportation when possible for residents to attend services. The Director at Garden House explained:

We always post funeral arrangements. … But we do try very hard to make sure we get ‘em at least to the visitation so that they can pay their respects ‘cause that kind of thing’s big to people at that age.

Residents in several homes told us that they attended services, but this was not a common occurrence and typically involved residents who were close friends of the deceased.

Overall, our data indicate that formal death acknowledgement depended on the actions of a key person, more so than on facility policy. In Feld House, where the prevalence of death was the highest, other than the memorial service for Janice planned by her daughter, no formal acknowledgement of death was observed. Acknowledgement was most common at Caroline Place where the Activity Director was the key person. Having learned that death is “a part of reality” for residents, she tried to create an environment of greater openness, even holding a session with residents to discuss death.

Impact on Residents and Staff

A widespread expectation, at least hope, among residents was that their AL home would be their “last stop.” As one resident said, “I moved in, they take care of me, and I’ll die.” Another expected to leave “feet first.” Administrators expressed similar beliefs, as stated by the Director of The Highlands: “Usually most people leave because they die.”

Residents, in general, were pragmatic about death–their own and fellow residents. This attitude was rooted in the reality of old age, their beliefs about death, often religion based, and the situations of those who died. The following words from a resident of Caroline Place express a common viewpoint that death, for older people, is “a fact of life”: “You have to realize that death is part of living, or it’s part of life, anyway you want to put it, and I think you will be much better off if you can accept it, you know. “

Residents expressed various reasons for being “ready to die,” including pain associated with disease, belief in a better after life, joining a loved one, the burden of their own care, and having their “house in order.” A resident of The Highlands, in her 80s and impaired by two strokes, when asked what mattered most in life said: “My leaving. I got everything ready. It’s true. I’ll be better.” An 88-year-old man at Garden House stated, “My work here is done.” Another, who recently lost his wife, looked forward to meeting her: “I know as the days go we are getting to the point where we will be together again, and when we get together again, we won’t ever be separated again and that’s something to look forward to and anticipate.” For now he is just “waiting:” “You might be in a doctor’s office with all these people and after a while the door will open and the nurse says, ‘Mr. Wiley, you’re next.’ So, I’m sitting waiting for the door to open.” Although one administrator told us that residents “don’t really wanna discuss age and they don’t wanna discuss death,” we found, as another administrator said, “They talk about being ready to go all of the time.”

Such attitudes colored how residents responded to deaths of co-residents. As one resident at Pineview said about Barbara, “It’s okay. I’m happy for her. She wanted to go!” It was harder for residents to witness suffering than to accept death, especially when they were close to the deceased, as illustrated in field notes from Oakridge describing a resident who died in her apartment shortly after:

Mrs. Freeman began to cry and talk about how hard it was to see Mrs. Peters with a breathing tube down her nose and throat. She did not understand why Oakridge admits residents when they are in need of hospice care, and cannot understand why Mrs. Peters is still there. She started talking about how hard it is trying to be a friend to her and Jane [another resident] and how hard it is to watch them go down so quickly. She said she goes to visit her and it breaks her heart to see her in such bad shape.

Because of such attitudes regarding death and dying, as well as the general lack of close co-resident relationships (see Kemp et al., 2012; Perkins et al., 2013), residents typically did not experience significant grief over the death of fellow residents. Comments such as, “Well you feel sorry for a half hour and then…” and “I didn’t feel any deep loss” were common. More often residents noted missing sharing meals or activities with a particular person, as expressed by a resident at Caroline Place about a recent death:

Well it was hard in the beginning because she ate with me, you know, and there was conversation between us and I miss that. … Sally and I talk a lot about being native Atlantans and what we remember and how things used to be and high school and that kind of thing. But I coped with it.

Responses to death, however, were different when co-residents were spouses or siblings. Fifteen of the residents who died were members of co-resident couples; in almost all cases the remaining spouse suffered deep sorrow. Data also indicate that AL staff often experienced grief, especially with close relationships, as illustrated in field notes following Barbara’s death at Pineview:

They were all speaking in hushed tones and Karen informed me that Barbara had just passed away just about 45 minutes ago. Karen began to tear up as she told me the sad news which, in turn, made me cry… The staff was visibly upset and shaken by the incident. It was no secret that Barbara was one of their favorites.

Discussion

In this paper we present our preliminary model (Figure 1) for how EOL care transitions are negotiated in AL. We use a social ecological framework and an interpretive lens to examine EOL events and processes, considering the social nature of death and its AL context. As shown in the figure, residents’ EOL care transitions and care arrangements are variably shaped by multiple intersecting factors at the individual-, facility-, local community-, and federal and state policy-levels and in turn alter the surrounding social and physical environments.

Figure 1.

Negotiating EOL Care Transitions in Assisted Living

This model affirms and supports our earlier work investigating the process of aging in place in AL (Ball et al., 2004; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012), which found that residents’ ability to remain in AL was principally a function of the “fit” between the capacity of both residents and facilities to manage decline. Multilevel, interactive factors, similar to those explicated here, influenced the capacity to manage decline and resident-facility fit resulted from and influenced the decline management process. Here we extend the examination of aging (or dying) in place to explore EOL transitions in AL, including the prevalence of death, residents’ dying trajectories and EOL care arrangements, and the impact of EOL on the AL environment, including what we label EOL presence, referring to indicators in a setting’s social and physical environment of death and dying. These findings reinforce previous AL research which elucidated how social and institutional change in AL and the multiple and ever-changing cultural contexts of residents lives shape their experiences over time (Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012).

Resident deaths in our eight study homes ranged from 1–29%, with an overall prevalence of 15%, which parallels reports of AL deaths in other studies (Golant, 2004; Munn et al., 2006; Zimmerman, et al., 2005). Following Glaser and Strauss (1968), we identified three dying trajectories among residents based on duration and slope. The majority (61%) of residents who died represented a gradual trajectory, resonant with the older age and chronic disease co-morbidity of AL residents (Caffrey et al., 2012). The widespread nature of this dying trajectory points to a key factor affecting EOL care in AL and other LTC settings, which is the difficulty with chronic illness of deciding when a person is in fact facing imminent death (Institute of Medicine, 2003). As Bern-Klug (2009:496) emphasizes in her study of EOL in nursing homes, the social reality of dying is constructed by the people involved in care, including the resident, family members, staff, and physicians, and the social designation of death has important implications for resident care and is in fact a “necessary first step” to improving EOL care. Our findings provide some evidence for varying social definitions of dying among care partners that affected resident care, particularly the utilization of hospice.

Our data illuminate the care arrangements of AL residents at EOL. Although varying, the majority were characterized by collaborations of AL staff with other care partners, including family members, hospice workers, and private aides. Other analyses from this AL study show that residents’ care arrangements, or care convoys, can change over time and are comprised of AL care workers, their families and friends, and formal caregivers from outside AL ( Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013). Nearly all residents (99%) participating in quantitative surveys included family in their support networks; 29% identified other residents, and AL staff and friends outside the setting as network members (Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2013). The importance of informal support in promoting dying in place also is corroborated in earlier AL work (Ball et al., 2004).

Our findings provide evidence that hospice enables dying in place in AL and leads to improved outcome for residents and facilities, supporting other AL research documenting the positive effects of hospice for residents and staff (Munn et al., 2006, 2008). Similar to other studies (Cartwright et al., 2009; Dobbs, et al., 2006), we found that facility and resident factors, including administrator knowledge and support and resident attitudes and clinical conditions, influenced hospice use. The use of privately paid care aides further facilitated dying in place for some residents. As found in our other AL work (Ball et al., 2004; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012), utilization of this type of support depends on the financial resources of residents and their families and typically is possible only in the higher end AL facilities.

Our research helps substantiate the growing EOL presence in the changing world of AL. Similar to residents depicted in earlier qualitative studies in nursing homes (Gubrium, 1975), AL residents regularly experience and witness death and dying, and, as Gubrium (1975:198) found, frequently “define their futures” in death terms. We found that residents typically view death as normal and inevitable, and for some respite from pain and feeling burdensome to others, rather than an event to be feared. A study of 272 CCRC residents, found that many AL and nursing home residents referred to death as an escape, possibly indicating apathy, boredom, and a desire to avoid a further decline (Shippee, 2009). Davis-Berman’s (2010) qualitative inquiry of how CCRC residents think about death found an acceptance of death and lack of fear among the majority of respondents across independent, AL, and nursing home settings, although healthier residents were not necessarily ready to die.

In the current study, except for the death of a spouse or sibling, residents did not experience significant grief when co-residents died, outcomes influenced in part by the general lack of close relationships among co-residents (Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2013) and residents’ attitudes toward death. Similar to Davis-Berman’s (2010) findings among CRC residents, we found that watching dying and decline often was more painful for residents than the reality of death. In contrast, staff tended to experience higher levels of grief related to resident deaths, owing principally to the closeness of previous ties. Studies in AL (Ball, Lepore, Perkins, Hollingsworth, Sweatman, 2009; Kemp, Ball, Hollingsworth, & Lepore, 2010) and nursing homes (Bowers, Esmond, & Jacobson, 2000; Moss, Moss, Rubinstein, & Black, 2003) provide evidence of the close nature of staff-resident relationships, as well as the negative impact of resident death on staff. Although resources are typically limited in AL for grief support and EOL training, ours and other data (Munn et al., 2008) show that hospice personnel can be an important source of support when residents die.

In our study, the most common avenues of death communication were word of mouth or through various environmental clues. Staff rarely provided, and frequently concealed, death information, despite residents’ expressed preferences to know. Gubrium (1975) found similar incongruity between the attitudes and behaviors of nursing home staff and residents, as well as varying use of the physical environment to either hide (staff) or obtain clues (residents) about deaths. Other AL research (Eckert, Carder, Morgan, Frankowski, & Roth, 2009) also noted the limited communication regarding death. Such findings are consistent with the conclusion of the Institute of Medicine (1997) that people in the U.S. in general shun discussions of EOL.

The present study has a number of limitations. First the data utilized derive from a study that did not specifically address EOL and interviews with residents and staff did not inquire directly about EOL experiences, care, attitudes, and preferences. Researchers, however, were struck by how prevalent EOL discussions, care, and experiences were in the environment and how they affected social relationships, the main focus of study. Further, informal caregivers and external care workers were not interviewed. Additionally the study was set in Georgia. Although Georgia’s regulatory structure is comparable to the majority of states and our sample included a wide range of facility types, inclusion of other states and greater numbers of facilities would provide support for our findings and confirm their transferability to other AL settings nationwide. Despite these limitations, findings presented here fill an important void in the existing literature and provide a good basis for future research and, while not generalizable, provide important insights about EOL in AL that may be transferable to similar settings.

In conclusion, EOL care is a growing phenomenon in AL and, given the trends toward older and frailer residents and the growing number of states, including Georgia, making regulatory and statutory changes to support dying in AL, this phenomenon will continue to increase. Our research shows that death and dying lead to an EOL presence in AL and affects those witnessing EOL processes and events as well as those near death. Future research needs to examine in depth the viewpoints of AL stakeholders to better understand their attitudes and preferences regarding EOL care and the growing EOL presence. Our findings further make clear that in the majority of cases, EOL care must be supported by collaborative arrangements of care partners and that hospice care is a critical component. Research needs to further investigate these care arrangements to gain better understanding of how they work and how best to support them in AL and improve the quality of EOL care.

Highlights.

Death and dying lead to an EOL presence in AL and affects those witnessing EOL processes and events as well as those near death.

Our conceptual model depicts the range of multilevel intersecting factors that shape how EOL care transitions are negotiated in AL.

EOL care must be supported by collaborative arrangements of care partners and that hospice care is a critical component.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline Workers in Assisted Living. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Connell BR, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Elrod CC, Combs BL. Managing decline in assisted living: The key to aging in place. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S202–S212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.s202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Communities of care: Assisted Living for African American Elders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Perkins MM, Patterson VL, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Quality of life in assisted living facilities: Viewpoints of residents. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2000;19:304–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bern-Klug M. A framework for categorizing social interactions related to end-of-life care in nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(4):495–507. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers BJ, Esmond S, Jacobson N. The relationship between staffing and quality in long-term care facilities: Exploring the view of nurse aides. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2000;14:55–64. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Moss A, Rosennoff E, Harris-Kojetin L. Residents living in residential care facilities: United States, 2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright JC, Kayser-Jones J. End-of-life-care in assisted living facilities: Perceptions of residents, families, and staff. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2003;5:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright JC, Miller L, Volpin M. Hospice in assisted living: Promoting good quality care at end of life. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(4):508–516. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs DJ, Hanson L, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Munn J. Hospice attitudes among assisted living and nursing home administrators, and the long-term care hospice attitudes scale. Journal of Palliative Care. 2006;9:1388–1400. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Carder PC, Morgan LA, Frankowski AC, Roth EG. Inside assisted living: The search for home. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Awareness of dying. Chicago: Aldine; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Time for Dying. Chicago: Aldine; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Golant SM. Do impaired older persons with health care needs occupy U.S. assisted living facilities? An analysis of six national studies. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S68–79. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. The future status of assisted living residences: A response to uncertainty? In: Golant S, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gruneir A, Mor V, Weitzen S, Truchil R, Teno J, Roy J. Where people die: A multilevel approach to understanding infleunces on site of death in America. Medical Care Research & Review. 2007;64:351–376. doi: 10.1177/1077558707301810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium J. Living and Dying at Murray Manor. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes C, Rose M, Phillips C. A national study of assisted living for the frail elderly. Executive summary: Results of a national survey of facilities. Beachwood, OH: Myers Research Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde J, Perez R, Reed PS. The old road is rapidly aging. In: Golant SM, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. Baltimore, MD: 2008. pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Institute of Medicine. Approaching death: Improving care at the end-of-life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumney JR, Foley KM, Smith TJ, Gelband H, editors. Institute of Medicine. Describing death in America: What we need to know. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Negotiating transitions in later life: Married couples in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2008;27(3):231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Married couples in assisted living: Adult children’s experiences providing support. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:639–661. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11416447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Hollingsworth C, Lepore MJ. Connections with residents: “It’s all about the residents for me”. In: Ball Mary M, Perkins Molly M, Hollingsworth Carole, Kemp Candace L., editors. Frontline Workers in Assisted Living. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Sweatman WM, Luo S, Stanley V. Strangers and friends: Residents’ social relationships in assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(Suppl 1):278. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Perkins MM. Convoys of care: theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. Journal of Aging Studies. 2013;27(1):15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002. doi: 0.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroi I, Samus Q, Rosenblatt A, Onyike C, Brandt J, Baker A, et al. A comparison of small and large assisted living facilities for the diagnosis and care of dementia: The Maryland Assisted Living Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;22:224–232. doi: 10.1002/gps.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn J. A commentary: Where to live while dying. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(Special Issue III):68–70. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VW. Organizational features of terminal status passage in residential facilities for the aged. Urban Life. 1975a;4:349–367. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VW. Socialization for impending death in a retirement village. The American Journal of Sociology. 1975b;80:1122–1144. doi: 10.1086/225947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metlife Mature Market Institute. The 2011 Metlife market surveyof nursing home, assisted living, adult day services, and home carecosts. Westport, CT: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mollica R, Houser A, Ujvari K. Assisted living and residential care in the States in 2010. AARP Public Policy Institute; Washington, D.C: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moss M, Moss S, Rubinstein R, Black H. The metaphor of “family” in staff communication about dying and death. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;59:S290–S296. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.5.s290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn JC, Dobbs D, Meier A, Williams CS, Biola H, Zimmerman S. The end-of-life experience in long-term care: Five themes identified from focus groups with residents, family members, and staff. The Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):485–494. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn JC, Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Mitchell CM. Is hospice associated with improved end-of-life care in nursing home and assisted living facilities? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:490–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Kemp CL, Hollingsworth C. Social relationships and resident health in assisted living: An application of the Convoy Model. The Gerontologist. 2013 doi: 10.1093/geront/gns124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C. Relational autonomy in assisted living: A focus on diverse care settings for older adults. J Aging Studies. 2012;26(2):214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein RL. The ethnography of the end of life: The nursing home setting. In: Lawton MP, editor. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics: Focus on the end of life: Scientific and social issues. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Savishinsky JS. The ends of time: Life and work in a nursing home. New York: Bergin & Garvey; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Hanson L, Mitchell CM, Riedel-Leo C, Custis-Buie V. End of-life care in assisted living and related residential settings: Comparison with nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:1587–1594. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Seplaki C, Biagtan M, DuPreez A, Cleary J. Characterizing hospice services in the United States. Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):25–31. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RI. Direct care workers in long-term care and implications for assisted living. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, AL, GB, Morgan LA, Hebel JR, et al. How good is assisted living? Findings and implications from an outcomes study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2005;60B:S195–S204. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.s195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]