Abstract

Purpose

To examine school socioeconomic status (SES) in relation to school physical activity-related practices and children’s physical activity.

Design

A cross-sectional design was used for this study.

Setting

The study was set in 97 elementary schools (63% response rate) in two U.S. regions.

Subjects

Of the children taking part in this study, 172 were aged 10.2 (standard deviation (SD) = 1.5) years; 51.7% were girls, and 69.2% were White non-Hispanic.

Measures

School physical education (PE) teachers or principals responded to 15 yes/no questions on school physical activity-supportive practices. School SES (low, moderate, high) was derived from the percent of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch. Children’s moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during school was measured with accelerometers.

Analysis

School level analyses involved linear and logistic regression; children’s MVPA analyses used mixed effects regression.

Results

Low-SES schools were less likely to have a PE teacher and had fewer physical activity-supportive PE practices than did high-SES schools (p < .05). Practices related to active travel to school were more favorable at low-SES schools (p < .05). Children attending high-SES schools had 4.4 minutes per day more of MVPA during school than did those at low-SES schools, but this finding was not statistically significant (p = .124).

Conclusion

These findings suggest that more low- and moderate-SES elementary schools need PE teachers in order to reduce disparities in school physical activity opportunities and that PE time needs to be supplemented by classroom teachers or other staff to meet guidelines.

Keywords: Active Travel to School, Physical Education, Policy, Recess, Prevention Research, Manuscript format: research, Research purpose: relationship testing, Study design: nonexperimental, Outcome measure: behavioral, Setting: school, Health focus: fitness/physical activity, Strategy: policy, Target population age: youth, Target population circumstances: income level

PURPOSE

Regular physical activity in children can support academic performance, on-task behavior, weight control, and cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health, as well as reduce the likelihood of developing chronic disease in adulthood.1 Given the amount of time children spend at school, schools are an important setting for physical activity and are recommended to provide children with at least 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily.2–4 However, a recent study found that only 45% of schools in two U.S. metropolitan areas were meeting this guideline.5

Economic factors may impact the ability of schools to better incorporate physical activity practices into the school day. However, economic disparities in school physical activity policies or practices, as well as children’s physical activity during school, have been investigated in only a few U.S.-based studies to date. These studies found that schools in low-income areas were less likely to offer recess6 and provided fewer physical activity-supportive practices (e.g., no certified physical education [PE] teacher, no after-school sports) than those in high-income areas.7 A more recent study in elementary schools found that predominately White non-Hispanic schools had better recess practices, gymnasium facilities, and playground facilities as compared to predominately Latino and predominately Black schools.8 Findings regarding children’s physical activity during school show similar disparities, with one study finding that students in more affluent schools spent 20% more time engaged in MVPA during PE than did students in low-income schools.9

The aforementioned studies investigated economics disparities in only a single or relatively few physical activity-related school practices, with one exception that investigated middle school practices.7 The present study aimed to add to this limited body of evidence by investigating the association of school socioeconomic status (SES) to 15 existing school physical activity practices related to PE, recess, classroom, and after-school time, as well as children’s objectively measured MVPA during school. Schools were also classified into groups, based on the practices they implemented, and SES was investigated as a possible explanatory factor of the classifications.

METHODS

Participants

Data for the present study were from two larger studies: an observational study of neighborhood environments and children’s physical activity (Neighborhood Impact on Kids [NIK]; N = 723)10 and a community-based obesity prevention intervention (MOVE; N = 541).11 Children in NIK had been recruited from neighborhoods, and those in MOVE were recruited around recreation centers. Both studies used targeted phone calls to households that had a child in the study age range. The details of the selection of the schools and children have been described previously.5 The NIK and MOVE studies did not involve recruitment or data collection at schools, and some children participated in these studies when school was not in session (e.g., during summer). The present study, which measured school practices and derived accelerometer physical activity during school hours, was an ancillary study of the NIK and MOVE samples.

Elementary schools in the Seattle/King County, Washington, and San Diego County, California, metropolitan areas were selected for inclusion in the present study if they had a child enrolled who was a participant in the NIK or MOVE studies in 2009–2010. During the spring of 2012, a PE teacher (or principal when there was no PE teacher), from each identified school was contacted to complete a questionnaire to assess their school’s practices related to physical activity. One hundred and fifty-four schools were contacted, and 97 complete surveys were returned via postal mail or Internet (63% response rate). Forty-eight percent of the responding schools were located in San Diego County.

Children in the NIK and MOVE studies (N = 172) were included in the present analyses if they participated when school was in session (e.g., not during the summer). Children were 10.2 (standard deviation [SD] = 1.5) years of age, 51.7% were girls, 69.2% were White non-Hispanic, and 79.7% were from the NIK study. An average of 1.8 (SD = 1.5) children participated from each school.

Measures

School Physical Activity Practices

Survey items were selected from the School Physical Activity Policy Assessment (S-PAPA) tool,12 and some adaptations were made. The survey was kept brief to maximize response rate, and the items hypothesized to have the highest reach and impact on physical activity, based on findings from previous studies, were retained. The survey asked about 15 practices covering in-school time, including PE, recess, and classroom time, as well as practices covering after-school time. The following yes/no questions were asked about in-school practices: whether (1) the school had a PE teacher (could include a PE aide), (2) training was provided to increase MVPA in PE, (3) recess was supervised by a classroom teacher, (4) organized activities (e.g., walking programs, games) were provided during recess, (5) classroom teachers were provided training on classroom physical activity breaks, and (6) classroom teachers implemented classroom physical activity breaks. The after-school practices yes/no questions were as follows: whether (1) children were encouraged to engage in active travel to school, (2) the school participated in a Safe Routes to School (SRTS) program,13 (3) there were crossing guards, (4) there were interscholastic sports, and (5) there were intramural sports.

Informants also reported the (1) number of minutes/PE lesson, (2) number of PE lessons/week, (3) number of students per PE lesson, (4) average length of recess periods, and (5) average number of students per supervisor during recess. The minutes/PE lesson item was multiplied by the number of PE lessons/week item to determine number of PE minutes/week. Because state laws14,15 and formal guidelines2,4,16 exist for PE minutes/week and recess minutes/day, these variables were dichotomized as ≥100 min/wk for PE (the mandated amount in California and Washington) and ≥20 min/period for recess. The PE class size and recess students/teacher items were dichotomized in accordance with analyses conducted in a previous study of these practices and children’s physical activity.5

School Demographic Characteristics

School names were matched with state department of education data to identify the percent of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL).17,18 FRPL was divided into three even groups based on the distribution of the data, with 40.1% to 100% FRPL representing low SES, 13.1% to 40% FRPL representing moderate SES, and 0% to 13% FRPL representing high SES. These data sources were also used to identify the total number of teachers and students at each school as well as the proportion of students who were White non-Hispanic.

Children’s Physical Activity

Waist-worn Actigraph accelerometers, which have good validity for assessing physical activity in children, were used to assess children’s physical activity during school.19 The accelerometer data collection was part of the NIK and MOVE studies. Children were mailed accelerometers and asked to wear the devices for 7 days for all waking hours, including weekdays and weekend days. The accelerometers were returned via postal mail at the end of the 7 days. Ninety-one percent of children included in the present study wore the Actigraph model GT1M, and the remaining wore model 7164; the devices recorded acceleration at 30-second epochs. Daily minutes of MVPA were calculated using the 4-metabolic equivalent of task (4-MET) Freedson age-based thresholds,20 which have been used for national prevalence estimates.21 Weekend days were excluded, and school start and end times unique to each individual school were used to calculate MVPA during school, thus eliminating non-school time from the analysis. Days with any nonwear time during school were removed from the analysis, with nonwear time defined as ≥20 minutes of consecutive 0 counts. After removing weekend days, days when school was not in session, and days when the accelerometer was removed for ≥20 minutes during school, 91% of children had ≥2 days of accelerometer monitoring, and mean monitoring time was 3.7 (SD = 1.7) days.

Analysis

Logistic regression models determined the odds of having each of the 15 school physical activity practices for low-, moderate-, and high-SES schools (school-level analyses). Analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc tests was used to investigate the association between SES and the number of school physical activity practices within PE, recess, classroom time, and after-school time, as well as total number of physical activity practices across all five domains. The association between SES and the number of practices from a list of the five practices that were most related to MVPA in a previous study5 was also investigated. A latent class analysis was performed to investigate whether schools fell into subtypes based on the physical activity practices they had. An analysis of covariance model tested whether the schools in each latent class differed by SES. Lastly, linear mixed effects regression models were used to investigate the association between school SES and children’s MVPA during school (participant-level analyses). The after-school practices were excluded from the latent class analysis and MVPA analysis because after-school time was not included in the calculation of children’s MVPA. The city was adjusted for in all models, and children’s age and gender and the study design factors were adjusted for in the mixed effects models. SPSS was used for fitting statistical models, and Mplus was used for the latent class analysis.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents characteristics of the schools studied, and Table 2 presents odds ratios for having each school implement a physical activity practice arranged by school SES. Five of the 15 practices differed by school SES. Low-SES schools were less likely to have ≤30 students per PE lesson than were high-SES schools, and low- and moderate-SES schools were less likely to have a PE teacher than were high-SES schools. Low-SES schools were more likely to provide ≥20 minutes per session of recess than were moderate-SES schools. Moderate-SES schools were more likely than high-SES schools to participate in a SRTS program, and low- and moderate-SES schools were more likely than high-SES schools to have crossing guards.

Table 1.

Elementary School Characteristics

| Total number of schools | 97 |

| Total number of school districts included | 25 |

| Percent of schools in San Diego County | 49.5 |

| Percent private schools | 12.4 |

| Mean (SD) full-time teachers/school | 26.9 (6.5) |

| Mean (SD) total students/school | 549 (166) |

| Mean (SD) percent of students White non-Hispanic | 53.7 (21.0) |

| Mean (SD) FRPL eligible | 30.8 (24.5) |

| SES categories* | |

| Number (%) of schools low SES | 32 (33) |

| Number (%) of schools moderate SES | 33 (34) |

| Number (%) of schools high SES | 32 (33) |

SD indicates standard deviation; FRPL, free or reduced-price lunch; SES, socioeconomic status.

Low SES = 40.1% to 100% FRPL; moderate SES = 13.1% to 40% FRPL; high SES = 0% to 13% FRPL.

Table 2.

Odds of Schools Implementing a Physical Activity Practice by School SES (N = 97)

| Percent of Schools with Practice

|

Low vs. High SES

|

Low vs. Moderate SES

|

Moderate vs. High SES

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Schools | Low-SES Schools | Moderate-SES Schools | High-SES Schools | OR (95% CI)* | p | OR (95% CI)* | p | OR (95% CI)* | p | |

| In-school practices | ||||||||||

| Provided ≥100 min/wk of PE | 18.8 | 15.6 | 27.3 | 12.5 | 1.06 (0.23, 4.94) | 0.943 | 0.22 (0.05, 0.97) | 0.045 | 4.90 (1.04, 23.01) | 0.044 |

| Had ≤30 students/lesson in PE | 66.7 | 59.4 | 72.7 | 84.4 | 0.25 (0.07, 0.99) | 0.049 | 0.79 (0.21, 3.03) | 0.729 | 0.28 (0.06, 1.29) | 0.101 |

| Had PE teacher | 72.9 | 62.5 | 63.6 | 93.8 | 0.10 (0.02, 0.56) | 0.009 | 3.50 (0.60, 20.41) | 0.164 | 0.04 (0.01, 0.28) | 0.001 |

| Provided training on MVPA in PE | 59.4 | 65.6 | 54.5 | 59.4 | 1.58 (0.54, 4.63) | 0.408 | 2.43 (0.77, 7.68) | 0.130 | 0.74 (0.26, 2.13) | 0.582 |

| Provided ≥20 min/period of recess | 58.3 | 71.9 | 42.4 | 62.5 | 1.44 (0.50, 4.17) | 0.506 | 3.19 (1.12, 9.13) | 0.030 | 0.45 (0.16, 1.21) | 0.114 |

| Had ≤75 students/supervisor during recess | 78.1 | 21.9 | 18.2 | 25.0 | 0.87 (0.27, 2.82) | 0.821 | 1.42 (0.41, 4.97) | 0.581 | 0.59 (0.17, 2.08) | 0.410 |

| Had recess supervised by non-classroom teacher | 78.1 | 75.0 | 84.8 | 71.9 | 1.65 (0.47, 5.75) | 0.434 | 0.72 (0.18, 2.82) | 0.637 | 2.25 (0.61, 8.31) | 0.226 |

| Provided activities during recess | 46.9 | 50.0 | 51.5 | 40.6 | 1.40 (0.52, 3.80) | 0.509 | 0.81 (0.29, 2.23) | 0.683 | 1.79 (0.62, 5.16) | 0.285 |

| Provided training on MVPA in classroom | 15.6 | 25.0 | 15.2 | 6.3 | 4.73 (0.83, 27.07) | 0.081 | 1.31 (0.32, 5.43) | 0.711 | 3.61 (0.57, 22.90) | 0.173 |

| Had implementation of MVPA in classroom | 54.2 | 53.1 | 63.6 | 50.0 | 1.05 (0.39, 2.86) | 0.923 | 0.62 (0.23, 1.70) | 0.351 | 1.89 (0.68, 5.26) | 0.225 |

| After-school practices | ||||||||||

| Encouraged active travel to school | 52.6 | 53.1 | 60.6 | 43.8 | 1.55 (0.57, 4.20) | 0.395 | 0.72 (0.27, 1.97) | 0.525 | 1.96 (0.73, 5.28) | 0.183 |

| Participated in SRTS | 28.9 | 28.1 | 42.4 | 15.6 | 2.08 (0.61, 7.16) | 0.244 | 0.51 (0.12, 1.47) | 0.213 | 4.00 (1.21, 13.18) | 0.023 |

| Had crossing guards | 73.2 | 81.3 | 84.8 | 53.1 | 5.42 (1.55, 18.89) | 0.008 | 1.09 (0.27, 4.45) | 0.906 | 5.34 (1.55, 18.38) | 0.008 |

| Had interscholastic sports | 30.5 | 34.4 | 18.2 | 25.0 | 1.53 (0.51, 4.56) | 0.445 | 2.72 (0.83, 8.94) | 0.099 | 0.66 (0.20, 2.19) | 0.501 |

| Had intramural sports | 23.3 | 21.9 | 15.2 | 15.6 | 1.65 (0.45, 6.01) | 0.449 | 2.09 (0.54, 8.02) | 0.284 | 0.96 (0.25, 3.68) | 0.946 |

SES indicates socioeconomic status; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PE, physical education; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity; SRTS, state or nationally funded Safe Routes to School program.

From logistic regression models adjusted for city.

The number of physical activity practices at schools differed by SES for PE practices, with low-SES schools having fewer PE practices than high-SES schools (see Table 3). There were trends for significance for after-school practices, with low- and moderate-SES schools having more after-school practices than did high-SES schools. There was no association between SES and recess practices, classroom practices, all practices, or the practices most related to children’s MVPA.

Table 3.

Number of School Physical Activity Practices by School SES (N = 97)

| Estimated Mean (SE) Number of Practices†

|

SES Group Differences (p)*

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low SES | Moderate SES | High SES | Low vs. High | Low vs. Moderate | Moderate vs. High | |

| All practices (10 items) | 7.19 (0.34) | 7.11 (0.34) | 6.73 (0.34) | 0.953 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| PE practices (4 items) | 2.09 (0.14) | 2.11 (0.14) | 2.54 (0.14) | 0.017 | 0.961 | 0.211 |

| Recess practices (4 items) | 2.20 (0.16) | 1.96 (0.16) | 2.00 (0.16) | 1.00 | 0.977 | 1.00 |

| Classroom practices (2 items) | 0.74 (0.11) | 0.82 (0.11) | 0.57 (0.11) | 0.524 | 1.00 | 0.477 |

| After-school practices (5 items) | 2.24 (0.21) | 2.18 (0.20) | 1.52 (0.21) | 0.081 | 1.00 | 0.063 |

| Practices most related to children’s MVPA‡ (5 items) | 2.50 (0.15) | 2.38 (0.15) | 2.70 (0.15) | 0.692 | 1.00 | 0.534 |

SES indicates socioeconomic status; SE, standard error PE, physical education; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity.

Adjusted for city.

The five physical activity practices were having a PE teacher, providing ≥100 min/wk of PE, having recess supervised by non-classroom teacher, providing ≥20 min/period of recess, and having ≥75 students/supervisor in recess; recess ratio was reverse coded because it was negatively related to MVPA.

From post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustments.

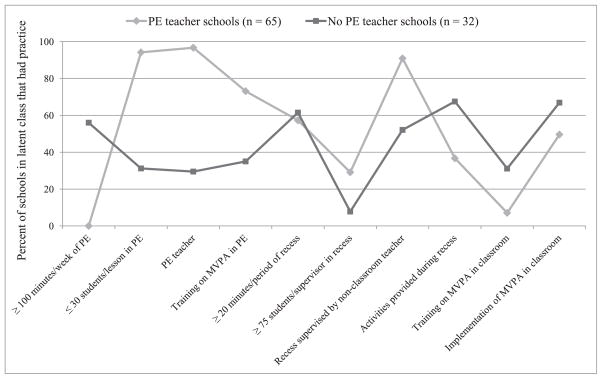

The latent class analysis revealed two latent classes (Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin, p = .004; Lo-Mendell-Rubin, p = .005; bootstrapped parametric p < .001; see Figure). Sixty-five of the 97 schools (67%) belonged to latent class 1, which was termed “PE teacher schools” because 98% of the schools in this latent class had a PE teacher. The second latent class was termed “no PE teacher schools” because only 30% of the schools in this latent class had a PE teacher. A greater percentage of schools in the PE teacher schools latent class had ≤30 students per PE lesson, provided training on MVPA in PE, had ≥75 students per supervisor in recess, and had recess supervised by someone other than a classroom teacher as compared to schools in the no PE teacher latent class. Moderate-but not low-SES schools were less likely to be in the PE teacher schools latent class (vs. no PE teacher schools latent class) as compared to high-SES schools (see Table 4).

Figure.

Latent Class Analysis of School Physical Activity Practices (N = 97)*

* Note: Recess ratio was coded as ≥ 75 students/supervisor because of its association with physical activity

Abbreviations: SES = socioeconomic status; PE = physical education; MVPA = moderate to vigorous physical activity.

Table 4.

School SES and Odds of Being in the PE Teacher Latent Class (N = 97)

| Number (%) of Schools in PE Teacher Latent Class | OR (95% CI) for Being in PE Teacher Latent Class (vs. no PE teacher latent class)* | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low SES | 20 (62.5) | 0.40 (0.10, 1.55) | 0.183 |

| Moderate SES | 19 (57.6) | 0.08 (0.01, 0.50) | 0.006 |

| High SES | 26 (81.2) | 1.00 (reference) | — |

SES indicates socioeconomic status; PE, physical education; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

From logistic regression model adjusted for city.

Table 5 presents children’s MVPA during school according to school SES and latent class membership. Children attending high-SES schools had 4.4 more minutes per day of MVPA during school than did those attending low-SES schools, although these differences were not statistically significant (p = .124). There were no differences in children’s school-based MVPA by latent class membership.

Table 5.

Children’s Accelerometer-Measured MVPA During School by School SES and Latent Class (172 children from 97 schools)

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Mean (CI)*

|

p for Group Differences

|

No PE Teacher Latent Class | PE Teacher Latent Class | No PE Teacher vs. PE Teacher Latent Class | |||||

| Low SES | Moderate SES | High SES | Low vs. High | Low vs. Moderate | Moderate vs. High | ||||

| MVPA min/day during school | 30.9 (25.3, 36.5) | 31.5 (26.4, 36.5) | 35.3 (28.4, 42.1) | 0.124 | 0.839 | 0.138 | 31.8 (24.9, 38.6) | 32.1 (26.1, 38.1) | 0.912 |

MVPA indicates moderate to vigorous physical activity; PE, physical education; SES, socioeconomic status; CI, confidence interval.

From mixed effects regression models adjusted for age, gender, city. and study design factors.

DISCUSSION

The present study found SES disparities in some school practices related to physical activity, with the most important finding being that high-SES schools were much more likely to have a PE teacher than were low-SES schools. The finding that low-SES schools without a PE teacher were still providing some, albeit fewer, opportunities for physical activity suggests that a majority of the obligation of providing PE and physical activity opportunities was fulfilled by classroom teachers. However, children at low-SES schools had 5 fewer minutes per day of MVPA than did those at high-SES schools, although this finding was nonsignificant, likely due to lack of power. These findings highlight the critical role that PE teachers play in children’s physical activity and the need for national policies and funding to support hiring PE teachers, particularly in low-SES schools.

Although high-SES schools were the most likely to have a PE teacher, they were the least likely to provide the state-mandated amount of PE, which is equivalent to 100 minutes per week.14,15 Furthermore, the latent class analysis revealed that none of the schools in the PE teacher schools latent class provided the mandated 100 minutes per week of PE. These findings could be because a single PE teacher in most schools (except very small ones) has insufficient time to provide 100 minutes of PE per week to all children. Thus, it is important for schools that are limited to only one PE teacher to train and support classroom teachers, other staff, and volunteers to provide supplemental PE of high quality.22 Schools with a PE teacher were also less likely to have supportive classroom physical activity practices. Thus, training classroom teachers to provide physical activity breaks or incorporate physical activity into academic lesson plans is likely to be a promising strategy for increasing children’s physical activity.

Some of the physical activity-supportive practices were more favorable at the low- or moderate-SES schools than at the high-SES schools. For example, low- and/or moderate-SES schools were the most likely to provide ≥20 minutes per session of recess, participate in SRTS, and have crossing guards to help facilitate walking to/from school. It is not surprising that low- and moderate-SES schools were more likely to participate in SRTS, because SRTS funding is often allocated for disadvantaged schools.13 The finding that high-SES schools were less likely to have crossing guards may be related to high-SES schools tending to be in less urban (more suburban) areas where children are less likely to walk or bike to campus.23

In the present study, the difference in MVPA between children at low- vs. high-SES schools was almost 5 minutes per day during school, which appears to be an important amount when taken across a week or school year. Future studies should examine whether school practices mediate the association between SES and children’s MVPA during school. Given that accelerometer studies have found that low-SES and racial/ethnic minority children were more active overall than their counterparts,24 implementing more physical activity-supportive practices that increase physical activity in low-SES schools could help address higher rates of obesity and related health conditions among lower-SES youth.25

Strengths of the present study are that a large number of schools in two U.S. regions were involved and that children’s physical activity was objectively measured across the entire school day using accelerometers. Nonetheless, it is important to note that these findings are from two cities and have limited generalizability, particularly because three large districts in San Diego declined to participate and the physical activity data included only an average of 1.8 children at each school. However, 97 schools is a substantial number compared to other studies of school physical activity practices (e.g., Lounsbery et al.,12 Young et al.7). Because school data were self-reported, it is possible that there was bias caused by lack of knowledge or social desirability by the respondent, and this reporting bias may have been greater in principals than in PE teachers. The brief survey in the present study included practices that were hypothesized to have the highest reach and impact regarding children’s physical activity during school, but it is important to note that there are other school practices that may impact children’s physical activity and be related to school SES that were not measured. Future studies should investigate other school physical activity practices, such as adherence to PE schedules and PE curriculum content, as well as barriers to providing such opportunities.

In this study there were few SES-related disparities in school physical activity practices, which is an encouraging finding. Low-SES schools were more engaged in supporting active travel to school. However, particular attention should be paid to low- and moderate-SES schools because they were much less likely to have a PE teacher than were high-SES schools, and having a PE teacher was a positive contributor to children’s physical activity during school. Evidence from the present study highlights the concern of schools not having PE teachers and suggests that when they are not available in sufficient quantities (i.e., large schools need more than one to meet recommended PE practices), there is a need to train and support classroom teachers and other school personnel to provide quality PE.

SO WHAT? Implications for Health Promotion Practitioners and Researchers.

What is already known on this topic?

Less than half of youth meet physical activity guidelines, and many schools do not meet guidelines for providing physical activity opportunities.

What does this article add?

The main SES disparity found was for having a PE teacher. Low-SES schools were less likely to have a PE teacher than were high-SES schools, and having a PE teacher was related to children’s physical activity.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Many low-SES schools are providing opportunities for physical activity, and other schools can learn from this. However, policies and funding need to be directed toward employing certified PE teachers in all schools, particularly those of low SES.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was from NIH ES014240, NIH DK072994, and The California Endowment. The lead author was funded by NIH T32 HL79891.

Contributor Information

Jordan A. Carlson, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California.

Alexandra M. Mignano, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California.

Gregory J. Norman, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California.

Thomas L. McKenzie, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, San Diego State University.

Jacqueline Kerr, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California.

Elva M. Arredondo, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, California.

Hala Madanat, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, California.

Kelli L. Cain, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California.

John P. Elder, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, California.

Brian E. Saelens, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

James F. Sallis, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed February 3, 2012];2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Available at: http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School health guidelines to promote healthy eating and physical activity. MMWR. 2011;60:1–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koplan J, Liverman CT, Kraak VI, editors. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pate RR, Davis MG, Robinson TN, et al. Promoting physical activity in children and youth: a leadership role for schools: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Physical Activity Committee) in collaboration with the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation. 2006;114:1214–1224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson JA, Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, et al. Elementary school practices and children’s objectively measured physical activity during school. Prev Med. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.08.003. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beighle A. Increasing Physical Activity Through Recess. San Diego, CA: Active Living Research; 2012. [Accessed May 21, 2013]. Available at: http://www.activelivingresearch.org/files/ALR_Brief_Recess.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young DR, Felton GM, Grieser M, et al. Policies and opportunities for physical activity in middle school environments. J Sch Health. 2007;77:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner L, Chaloupka FJ, Chriqui JF, Sandoval A. School Policies and Practices to Improve Health and Prevent Obesity: National Elementary School Survey Results: School Years 2006–07 and 2007–08. Vol. 1. Chicago, Ill: Bridging the Gap Program, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UCLA Center to Eliminate Health Disparities and Samuels & Associates. Failing Fitness: Physical Activity and Physical Education in Schools. Los Angeles, Calif: The California Endowment; 2007. [Accessed April 8, 2012]. Available at: http://www.calendow.org/uploadedFiles/failing_fitness.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD, et al. Obesogenic neighborhood environments, child and parent obesity: the Neighborhood Impact on Kids Study. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elder JP, Crespo NC, Corder K, et al. Childhood obesity prevention and control in city recreation centers and family homes: the MOVE/me Muevo Project. Pediatr Obes. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00164.x. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lounsbery MAF, McKenzie TL, Morrow JR, et al. School physical activity policy assessment. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10:496–503. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.4.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Safe Routes to School . Federal Safe Routes to School Program Progress Report, 2011. Chapel Hill, NC: National Center for Safe Routes to School; 2011. [Accessed March 15, 2012]. Available at: http://www.saferoutesinfo.org/program-tools/federal-safe-routes-school-program-progress-report. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergeson T, Davidson C, Domaradzki L. [Accessed May 21, 2013];Washington State K-12 Health and Fitness Learning Standards. Available at: https://www.k12.wa.us/healthfitness/Standards.aspx.

- 15.California State Board of Education. [Accessed May 21, 2013];California State Board of Education Policy #99-03. 1999 Jun; Available at: http://www.cde.ca.gov/be/ms/po/policy99-03-June1999.asp.

- 16.National Association for Sport and Physical Education. Standards and Position Statements. [Accessed month, date, year];Physical education guidelines. 2012 Available at: http://www.aahperd.org/naspe/standards/nationalGuidelines/PEguidelines.cfm.

- 17.California Department of Education. [Accessed May 21, 2013];Data & statistics. Available at: http://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/

- 18.State of Washington, Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. [Accessed May 21, 2013];Data and reports. Available at: http://www.k12.wa.us/DataAdmin/default.aspx#download.

- 19.Welk GJ, Corbin CB, Dale D. Measurement issues in the assessment of physical activity in children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007;71(suppl 2):S59–S73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedson P, Pober D, Janz K. Calibration of accelerometer output for children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(suppl 11):S523–S530. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185658.28284.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glickman D, Parker L, Sim LJ, et al., editors. Accelerating Progress In Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin SL, Lee SM, Lowry R. National prevalence and correlates of walking and bicycling to school. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitt-Glover MC, Taylor WC, Floyd MF, et al. Disparities in physical activity and sedentary behaviors among US children and adolescents: prevalence, correlates, and intervention implications. J Public Health Policy. 2009;30(Suppl 1):S309–S334. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]