Abstract

Dry eye is a potent stimulus of both innate and adaptive immune systems. At the nexus of the dry eye inflammatory/immune response is the dynamic interplay between the ocular surface epithelia and the bone marrow–derived immune cells. On the one hand, ocular surface epithelial cells play a key initiating role in this inflammatory reaction. On the other hand, they are targets of cytokines produced by activated T cells that are recruited to the ocular surface in response to dry eye. This interaction between epithelial and immune cells in dry eye will be thoroughly reviewed.

Keywords: dry eye, ocular surface epithelium, immune system

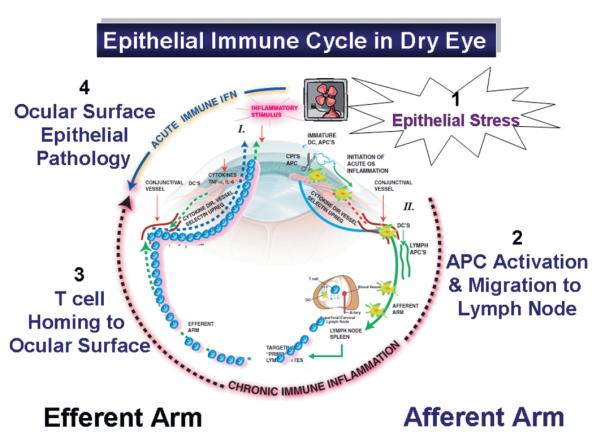

The proposed inflammatory/immune cycle of dry eye is presented in Figure 1. This cycle consists of an afferent arm, where desiccating stress on the ocular surface elicits an immune response, and an efferent arm, where activated CD4+ T cells home to the ocular surface and modulate epithelial differentiation.

FIGURE 1.

Afferent arm (right). Desiccating stress activates epithelial stress pathways stimulating production of cytokines, chemokines, and matrix metalloproteinases (1) that facilitate activation of dendritic cells and migration of dendritic cells to the regional lymph nodes (2). In the lymph nodes, dendritic cells present antigen to CD4+ T cells. Efferent arm (left). Primed and targeted CD4+ T cells emigrate from the lymph nodes and home to the ocular surface (3) where if conditions are favorable, they infiltrate the conjunctival epithelium. Cytokines produced by these CD4+ effector cells modulate epithelial differentiation and survival (4). IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. DC = dendritic cell; APC = antigen presenting cell; CPI = cornea proteases.

AFFERENT ARM

The afferent arm of the dry eye immune reaction is initiated by a stress response of the ocular surface epithelial cells to desiccation and/or increased tear osmolarity. Increased tear osmolarity in dry eye has been recognized for decades.1 Clinical studies have reported increases in mean tear osmolarity of about 10%–20% in tear samples collected from the inferior tear meniscus 1; however, ocular surface epithelial cells underlying areas of marked thinning or frank breakup of the tear layer may be subjected to much greater osmotic stress.2 This is supported by a study that found a doubling of tear osmolarity in an experimental murine model of dry eye using sodium ion concentration in tear washings collected from the entire ocular surface to measure tear osmolarity.3

Osmotic stress activates signaling pathways in a variety of cell types, including the ocular surface epithelia.4 We have reported that exposure to increased osmolarity in vivo or in vitro activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, particularly p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinases, and nuclear factor (NF)-κB in the ocular surface epithelia.5,6 These pathways regulate transcription of a wide variety of genes involved in the inflammatory/immune response. We have found that desiccating and osmotic stress, by MAPK activation, stimulates production of a variety of inflammatory mediators by the corneal epithelium, including interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IL-8 and a number of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs; MMP-1, -3, -9, -10, and -13).5–9 Epithelial-derived factors, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, can activate immature resident corneal dendritic cells and recruit dendritic cells into the cornea through upregulation of CC chemokine receptor 5 and major histocompatibility complex class II antigen.10,11 Dry eye also leads to a decrease in the number of conjunctival goblet cells, which produce and secrete the immunoregulatory molecule transforming growth factor-β2 that has been reported to suppress activation of dendritic cells on the ocular surface.12,13 Desiccating stress may also expose or release yet-to-be-determined autoantigens by the ocular surface epithelia through proteolytic cleavage of membrane antigens or by accelerating apoptosis and release of intracellular antigens.

Adoptive transfer models indicate that antigen-loaded antigen-presenting cells migrate from the ocular surface to regional lymph nodes where they present antigen to CD4+ T cells capable of reacting to ocular surface antigens. CD4+ T cells isolated from spleen and superficial cervical lymph nodes of mice subjected to desiccating stress have been shown to induce severe autoimmune lacrimal keratoconjunctivitis when they are adoptively transferred to nude mouse recipients.14

These findings suggest that ocular surface epithelial cells play a key role in the innate immune/inflammatory response to desiccating stress that facilitates the development of an adaptive immune response.

EFFERENT ARM

In the efferent arm of the immune cycle of dry eye (Fig. 1), activated CD4+ T cells migrate from the lymph nodes to the ocular surface and lacrimal glands, in which if conditions are favorable, they are recruited to the epithelia where the putative lacrimal keratoconjunctivitis–inducing autoantigen is located. In normal immunocompetent individuals, experimental evidence indicates that this process is inhibited by T regulatory cells in the regional lymph nodes and in the conjunctival epithelium.14 We have observed that dry eye decreases the numbers of CD8+ and CD103+ conjunctival intraepithelial T cells that may serve as a barrier to migration of pathogenic autoreactive CD4+ T cells into the conjunctival epithelium.15,16 T-cell recruitment to and retention in the ocular surface tissues may be facilitated by cytokines and chemokines that are produced by activated epithelia that alter the local immune milieu by increasing the expression of adhesion molecules by vascular endothelial cells and ocular surface epithelial cells.5,17 Increased production of MMPs by the ocular surface epithelia also facilitates migration of T cells through the epithelial basement membrane into the epithelium.9 Dry eye also appears to decrease levels of Fas ligand by the ocular surface epithelia, which has been found to play a role in immune privilege by stimulating apoptosis of Fas-expressing T cells.18

Cytokines released by the infiltrating CD4+ T cells are capable of altering conjunctival epithelial homeostasis. IL-17 alone or in conjunction with interferon (IFN)-γ or TNF-α has been found to stimulate the production of inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, IL-8, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, interferon-inducible protein (IP)-10, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, human leukocyte antigen-DR, and β-defensin-2 by mucosal epithelial cells.19–26 We have reported that IFN-γ decreases goblet cell differentiation and increases expression of cornified envelope precursor proteins such as involucrin and small proline-rich protein-2.15

The relationship between T-cell infiltration of the conjunctiva and loss of goblet cells has been observed in other inflammatory models. Chronic activation of NF-κB signaling in I kappa bata zeta (IKBz) knockout mice has been observed to induce CD4+ T-cell migration into the conjunctiva and marked goblet cell loss.27

These findings are consistent with the clinical features of human dry eye disease. A decrease of conjunctival goblet cell density is recognized as a sine qua non of aqueous tear deficiency.28 Furthermore, it is recognized that goblet cell loss is greatest in conditions associated with severe T-cell infiltration of the conjunctiva such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome, graft-versus-host disease, and mucus membrane pemphigoid.29–31 Furthermore, increased expression of cornified envelope precursor proteins and crosslinking transglutaminase-1 enzyme in the conjunctival epithelium has been observed in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and Sjögren syndrome.32,33

Finally, epithelial stress pathways activated by osmotic stress and T-cell cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α may contribute to the increased conjunctival epithelial apoptosis that has been observed in human and murine dry eye.34,35

THERAPEUTIC TARGETS

The above findings suggest that therapeutic strategies could be utilized to inhibit components of the inflammatory cycle of dry eye. Hydration of the ocular surface can be maintained with use of moisture chamber spectacles and therapeutic contact lenses—particularly the Boston lens, which serves as a liquid bandage.36 Osmoprotectants added to artificial tear solutions have been found to inhibit MAPK activation in the ocular surface epithelia in response to osmotic stress.37 Corticosteroids inhibit NF-κB–mediated production of numerous cytokines and chemokines.8,38,39 Tetracyclines inhibit MAPK activation and are potent inhibitors of MMPs.7,8,38 Cyclosporin A decreases the production of factors by activated T cells and has been found to inhibit ocular surface epithelial apoptosis and to increase conjunctival goblet cell density in humans and mice with dry eye.13,40–42 Autologous serum and constituents such as albumin have been found to have antiapoptotic effects on the ocular surface epithelia.43

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Eye Institute grants EY11915 (S.C.P.), EY014553 (D.-Q.L.), and EY016928-01 (C.S.d.P.); an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness; the Oshman Foundation, the William Stamps Farish Fund; the Hamill Foundation; and an unrestricted grant from Allergan (S.C.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilbard JP, Farris RL, Santamaria J., II Osmolarity of tear microvolumes in keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:677–681. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910050373015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols JJ, Mitchell GL, King-Smith PE. Thinning rate of the precorneal and prelens tear films. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2353–2361. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart P, Chen Z, Farley W, et al. Effect of experimental dry eye on tear sodium concentration in the mouse. Eye Contact Lens. 2005;31:175–178. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000161705.19602.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosette C, Karin M. Ultraviolet light and osmotic stress: activation of the JNK cascade through multiple growth factor and cytokine receptors. Science. 1996;274:1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo L, Li DQ, Doshi A, et al. Experimental dry eye stimulates production of inflammatory cytokines and MMP-9 and activates MAPK signaling pathways on the ocular surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4293–4301. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo L, Li DQ, Corrales RM, et al. Hyperosmolar saline is a proinflammatory stress on the mouse ocular surface. Eye Contact Lens. 2005;31:186–193. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000162759.79740.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li DQ, Chen Z, Song XJ, et al. Stimulation of matrix metalloproteinases by hyperosmolarity via a JNK pathway in human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4302–4311. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li DQ, Luo L, Chen Z, et al. JNK and ERK MAP kinases mediate induction of IL-1beta, TNF-alpha and IL-8 following hyperosmolar stress in human limbal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrales RM, Stern ME, De Paiva CS, et al. Desiccating stress stimulates expression of matrix metalloproteinases by the corneal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3293–3302. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamrah P, Liu Y, Zhang Q, et al. Alterations in corneal stromal dendritic cell phenotype and distribution in inflammation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1132–1140. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamrah P, Liu Y, Zhang Q, et al. The corneal stroma is endowed with a significant number of resident dendritic cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:581–589. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen L, Barabino S, Taylor AW, et al. Effect of the ocular microenvironment in regulating corneal dendritic cell maturation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:908–915. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.7.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pflugfelder SC, De Paiva CS, Villarreal A, et al. Effects of sequential artificial tear and cyclosporine emulsion therapy on conjunctival goblet cell density and transforming growth factor-beta2 production. Cornea. 2008;27:64–69. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318158f6dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niederkorn JY, Stern ME, Pflugfelder SC, et al. Desiccating stress induces T cell-mediated Sjogren’s syndrome-like lacrimal keratoconjunctivitis. J Immunol. 2006;176:3950–3957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Paiva CS, Villarreal AL, Corrales RM, et al. Dry eye-induced conjunctival epithelial squamous metaplasia is modulated by interferon-gamma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2553–2560. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon KC, De Paiva CS, Qi H, et al. Desiccating environmental stress exacerbates autoimmune lacrimal keratoconjunctivitis in non-obese diabetic mice. J Autoimmun. 2008;30:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon KC, De Paiva CS, Qi H, et al. Expression of Th-1 chemokines and chemokine receptors on the ocular surface of C57BL/6 mice: effects of desiccating stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2561–2569. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hori J, Joyce N, Streilein JW. Epithelium-deficient corneal allografts display immune privilege beneath the kidney capsule. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:443–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawaguchi M, Kokubu F, Fuga H, et al. Effect of IL-17 on ICAM-1 expression on human bronchial epithelial cells NCI-H 292. Arerugi. 1999;48:1184–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones CE, Chan K. IL-17 stimulates the expression of IL-8, growth related oncogene alpha and G-CSF by human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:748–753. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:950–957. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawaguchi M, Kokubu F, Huang SK, et al. The IL-17F signaling pathway is involved in the induction of IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 in bronchial epithelial cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1408–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Berg A, Kuiper M, Snoek M, et al. Interleukin-17 induces hyperresponsive interleukin-8 and interleukin-6 production to tumor necrosis factor-alpha in structural lung cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:97–104. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0022OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teunissen MB, Koomen CW, de Waal Malefyt R, et al. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma synergize in the enhancement of proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:645–649. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang SC, Tan XY, Luxenberg DP, et al. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2271–2279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueta M, Hamuro J, Yamamoto M, et al. Spontaneous ocular surface inflammation and goblet cell disappearance in I kappa B zeta gene-disrupted mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:579–588. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pflugfelder SC, Tseng SCG, Yoshino K, et al. Correlation of goblet cell density and mucosal epithelial mucin expression with rose Bengal staining in patients with ocular irritation. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:223–235. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawasaki S, Nishida K, Sotozono C, et al. Conjunctival inflammation in the chronic phase of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1191–1193. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.10.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas B, Cuhna R, Zafirakis P, et al. Cell populations and adhesion molecules expression in conjunctiva before and after bone marrow transplantation. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81:313–325. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice BA, Foster CS. Immunopathology of cicatricial pemphigoid affecting the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1476–1483. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura T, Nishida K, Dota A, et al. Elevated expression of transglutaminase 1 and keratinization-related proteins in conjunctiva in severe ocular surface disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirai N, Kawasaki S, Tanioka H, et al. Pathological keratinisation in the conjunctival epithelium of Sjogren’s syndrome. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh S, Song XJ, Farley W, et al. Apoptosis of ocular surface cells in experimentally induced dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:124–129. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo L, Li DQ, Pflugfelder SC. Hyperosmolarity-induced apoptosis in human corneal epithelial cells is mediated by cytochrome c and MAPK pathways. Cornea. 2007;26:452–460. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318030d259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenthal P, Croteau A. Fluid-ventilated, gas-permeable scleral contact lens is an effective option for managing severe ocular surface disease and many corneal disorders that would otherwise require penetrating keratoplasty. Eye Contact Lens. 2005;31:130–134. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000152492.98553.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corrales RM, Luo L, Chang EY, Pflugfelder SC. Effects of osmoprotectants on hyperosmolar stress in cultured human corneal epithelial cells. Cornea. 2008 doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318165b19e. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Paiva CS, Corrales RM, Villarreal AL, et al. Apical corneal barrier disruption in experimental murine dry eye is abrogated by methylprednisolone and doxycycline. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2847–2856. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almawi WY, Melemedjian OK. Negative regulation of nuclear factor-kappa B activation and function by glucocorticoids. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;28:69–78. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0280069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsuda S, Koyasu S. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine. Immunopharmacology. 2000;47:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halestrap AP, McStay GP, Clarke SJ. The permeability transition pore complex: another view. Biochimie. 2002;84:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strong B, Farley W, Stern ME, et al. Topical cyclosporine inhibits conjunctival epithelial apoptosis in experimental murine keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Cornea. 2005;24:80–85. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000133994.22392.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higuchi A, Ueno R, Shimmura S, et al. Albumin rescues ocular epithelial cells from cell death in dry eye. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:83–88. doi: 10.1080/02713680601147690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]