Abstract

Wnt signaling is important for cancer pathogenesis and is often upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) function as co-receptors or modulators of Wnt activation. Glypican-3 (GPC3) is a HSPG that is highly expressed in HCC, where it can attract Wnt proteins to the cell surface and promote cell proliferation. Thus, GPC3 has emerged as a candidate therapeutic target in liver cancer. While monoclonal antibodies to GPC3 are currently being evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies, none have shown an effect on Wnt signaling. Here, we first document the expression of Wnt3a, multiple Wnt receptors and GPC3 in several HCC cell lines, and demonstrate that GPC3 enhanced the activity of Wnt3a/β-catenin signaling in these cells. Then, we report the identification of HS20, a human monoclonal antibody against GPC3, which preferentially recognized the heparan sulfate chains of GPC3, both the sulfated and non-sulfated portions. HS20 disrupted the interaction of Wnt3a and GPC3 and blocked Wnt3a/β-catenin signaling. Moreover, HS20 inhibited Wnt3a-dependent cell proliferation in vitro and HCC xenograft growth in nude mice. In addition, HS20 had no detectable undesired toxicity in mice. Taken together, our results show that a monoclonal antibody primarily targeting the heparin sulfate chains of GPC3 inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling in HCC cells and had potent anti-tumor activity in vivo.

Conclusion

Here, we provide one of the first examples of an antibody directed against the heparan sulfate of a proteoglycan that showed efficacy in blocking Wnt signaling and HCC growth, suggesting a novel strategy for liver cancer therapy.

Keywords: Cancer therapy, Wnt3a, heparan sulfate proteoglycan, phage display, antibody engineering

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common and the third most lethal malignancy in the world.1 The majority of HCC cases are identified at an advanced stage when resistance to most chemotherapeutic drugs is greater. Given that the survival rate of HCC patients is very low, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic approaches.

Wnt signaling plays an important role in cancer pathogenesis and has been studied as a potential target for cancer therapy. In HCC, at least 95% of patients have either upregulation of Frizzled/Wnt expression or down-regulation of Frizzled(FZD) receptor inhibitors such as sFRP genes.2 Therefore, blocking Wnt signaling at the extracellular level would be a reasonable strategy for HCC therapy. Currently, there are several approaches used to block Wnt signaling. One approach involves monoclonal antibodies targeting Wnt ligand or Frizzled. Antibodies against Wnt1,3 Wnt2,4 and FZD7 5 have been shown to reduce the growth of different tumors. Another approach utilizes soluble Frizzled receptors to neutralize Wnt function. A soluble FZD8 domain shows anti-tumor activity in teratoma.6 A soluble FZD7 protein inhibits Wnt signaling and sensitizes HCC cell lines to doxorubicin treatment.7 Other studies show that targeting a key partner in the Wnt/Frizzled signaling complex can also block Wnt activity. For example, disturbing the Frizzled/Dishevelled interaction by a competitive peptide decreases Wnt signaling and induces apoptosis of Huh-7 cells.8 Anti-LRP6 antibody can inhibit both Wnt1 and Wnt3a mediated signaling.9

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are ubiquitously expressed on the cell surface and extracellular matrix (ECM) in animals. HSPGs participate in almost every step of tumor development: tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, immune surveillance evasion, tumor invasion and metastasis.10 HSPGs characteristically contain one or more heparan sulfate (HS) chains that are covalently linked to a core protein.11 It has been suggested that HS binds to a multitude of molecules, including Wnt proteins, growth factors, bone morphogenetic proteins, chemokines, lipases, as well as ECM.12–13 GPC3 is a member of the glypican family containing two HS chains and anchored to the cell surface through a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linkage.14 GPC3 is highly expressed in 70–100% of HCCs but not in normal adult tissues.15 The expression of GPC3 is correlated with poor clinical prognosis for HCC survival.16 Silencing GPC3 was reported to inhibit HCC cell growth or promote cell apoptosis.17–20 Others suggested that GPC3 functions as a storage site for Wnt and facilitates Wnt/Frizzled binding for HCC growth.21 Interestingly, soluble GPC3 protein (GPC3ΔGPI) can inhibit HCC cell growth and tumorigenesis. It may act as a dominant negative form to compete with endogenous GPC3, likely by neutralizing GPC3 binding molecules.22–23 These studies indicate the role of GPC3 in HCC growth and suggest that GPC3 might be a potential target to block Wnt signaling.

Monoclonal antibodies against GPC3 have been made and tested in preclinical and clinical studies for liver cancer therapy.24–26 In particular, one of them is currently being evaluated in a Phase 2 clinical trial for the treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic HCC (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01507168). However, all of these antibodies were raised against the core protein of GPC3. No GPC3 antibody that disturbs Wnt signaling has been reported.

In the present study, we generated HS20, a human monoclonal antibody recognizing the HS chains of GPC3, and showed that the antibody disturbs the GPC3/Wnt3a complex and blocks Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The new antibody inhibits cell proliferation in vitro, and inhibits HCC xenograft tumors in mice without detectable in vivo toxicity. HS20 is a unique human antibody to GPC3, which has potential for liver cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Huh-1, Huh-4, Huh-7 and SK-hep1 cell lines were obtained from the NCI Laboratory of Human Carcinogenesis. HepG2, Hep3B and A431 (human epithelial carcinoma) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). A431-GPC3 stable line was generated by transfecting GPC3 cDNA (Genecopia, Rockville, MD) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA). Hep3B knockdown cells were constructed by using GPC3 gene-specific sh-RNA as described before.26 HEK293 SuperTopflash stable cell line was a kind gift from Dr. Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins Medical School.27 L cell line and L-Wnt3a cell line were generously provided by Dr. Yingzi Yang, NHGRI, NIH. Conditioned media were prepared as previously described28 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine.

Single-chain variable fragment (scFv) selection by phage display

The human scFv HS20 was selected from previously reported Tomlinson I + J phage display libraries (Geneservice Ltd, Cambridge, UK).29 The phage libraries were subjected to three rounds of panning on recombinant GPC3 proteins following an established laboratory protocol.30

Antibody production

The heavy chain and light chain sequences of HS20 scFv were amplified by adding IL-12 signal peptide and were inserted into the expression vectors, pFUSE-CHIg-HG1 and pFUSE2-CLIg-hk (Invivogen, San Diego, CA), respectively. The plasmids were transiently co-transfected into HEK-293T cells. The medium was collected and the HS20 IgG was purified using a Protein A Hi-Trap column (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of purified HS20 IgG was determined by SDS-PAGE and A280 absorbance on a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Asheville, NC).

Animal testing

All mice were housed and treated under the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Hep3B cells or HepG2 cells were suspended in 200 μl of PBS and inoculated subcutaneously into 4 to 6 week-old female BALB/c nu/nu nude mice (NCI- Frederick Animal Production Area, Frederick, MD). Tumor dimensions were determined using calipers and tumor volume (mm3) was calculated by the formula V = ab2/2, where a and b represent tumor length and width, respectively. When the average tumor size reached approximately 100 mm3, the mice were intravenously injected with 20 mg/kg of HS20 or human IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) three times a week. Mice were euthanized when the tumor size reached 1000mm3.

In vivo toxicology studies

BALB/c nu/nu mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 5×106 HepG2 cells. When tumors reached an average volume of 100 mm3, mice were administered HS20 (i.v. every other day, 20 mg/kg). PBS was used as the vehicle control. When tumor sizes of the control group reached 1000 mm3, samples (3 mice/ group) were processed for complete blood counts (CBC), serum chemistry and organ weights.

Statistics

All the representative results were repeated in at least three independent experiments. All group data (except those indicated) were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of a representative experiment performed in at least triplicates and similar results were obtained in at least three independent experiments. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were applied to determine significant differences, with P* <0.05 defined as significant. The GraphPad Prism 6 program (San Diego, CA) was used to statistically analyze the results.

Results

GPC3 promotes Wnt activation in HCC

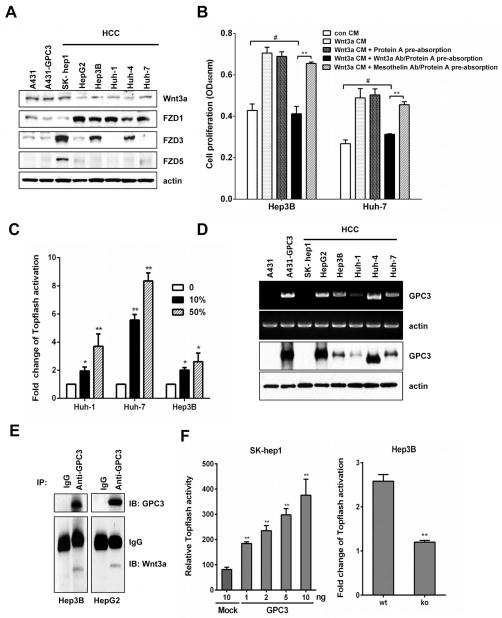

To investigate the effect of GPC3 on canonical Wnt/β–catenin signaling in HCC cells, we first examined the expression of Wnt ligand and Frizzled receptors in different HCC cell lines. We found that Wnt3a and receptors capable of transducing the β–catenin pathway were expressed in all of the cell lines, in particular FZD1 in HepG2, Hep3B, Huh-1, Huh-4 and Huh-7 cells and FZD5 in SK-hep1 cells (Fig. 1A). When we treated Hep3B and Huh-7 cells with Wnt3a-conditioned media (CM), their proliferation increased significantly. However, after we removed Wnt3a with an anti-Wnt3a antibody, Hep3B and Huh-7 cell proliferation was completely blocked, indicating that Wnt3a was the dominant growth factor present in the CM (Fig. 1B). As a control, the media pre-absorbed by an isotype control antibody specific for MSLN retained its ability to stimulate cell proliferation. Furthermore, we demonstrated that Wnt3a CM can induce Wnt/β-catenin Topflash reporter activity in native HCC cells (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that Wnt3a-mediated canonical Wnt signaling mediates HCC cell proliferation.

Figure 1. Activation of Wnt signaling by GPC3 in HCC.

(A) Wnt3a, FZD1, FZD3 and FZD5 expressions in HCC cell lines. (B) 50% Wnt3a CM was incubated with Wnt3a antibody or MSLN antibody and then the antibody-Wnt3a complex was removed by Protein A-Agarose beads. The pre-absorbed CM was added to Hep3B and Huh-7 cells. Cell proliferation was measured by WST-8 assay at 48 hours after treatment. CM: conditioned media, MSLN: mesothelin. The data represent the mean ± SD (**P <0.01 and #P > 0.05). (C) Topflash activity in Huh-1, Huh-7 and Hep3B cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were starved for 2 hours and then treated with 10% or 50% Wnt3a CM. Topflash activity was measured 24 hours later. The data represent the mean ± SD (*P <0.05 and **P <0.01). (D) GPC3 expression in HCC cell lines was measured by RT-PCR (top panel, showing full length GPC3) and Western blots (bottom panel, showing GPC3 core protein). (E) Immunoprecipitation assays detected the interaction of GPC3 and Wnt3a in Hep3B cells and HepG2 cells. The immunoprecipitated complex was detected with an anti-Wnt3a antibody or an anti-GPC3 antibody (YP7). (F) Topflash activity in GPC3-transfected SK-hep1 cells and GPC3 knockdown Hep3B cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were starved for 2 hours and then treated with 50% (SK-hep1 cells) or 100% Wnt3a CM (Hep3B cells). Topflash activity was measured 24 hours later in SK-hep1 cells and 48 hours in Hep3B cells; GPC3 knockdown efficiency was shown in Fig. 5C. Wt: wild type; ko: knockdown. The data represent the mean ± SD (**P <0.01).

Using a combination of mRNA and protein analysis, we determined that five out of six HCC lines expressed GPC3 (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, we found a smaller size of GPC3 cDNA in Huh-4. Sequencing analysis showed that the GPC3 cDNA in Huh-4 lacked exon 2. Furthermore, we found that GPC3 co-immunoprecipitated with Wnt3a in Hep3B and HepG2 cells (Fig. 1E). Overexpression of GPC3 in SK-Hep1 cells enhanced Wnt/β-catenin Topflash reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner. Alternatively, GPC3 knockdown in Hep3B cells significantly decreased the response to Wnt3a stimulation (Fig. 1F; see Fig. 5C for assessment of shRNA efficiency). Taken together, these data suggest that GPC3 is an important molecule capable of increasing Wnt/β-catenin activation in HCC.

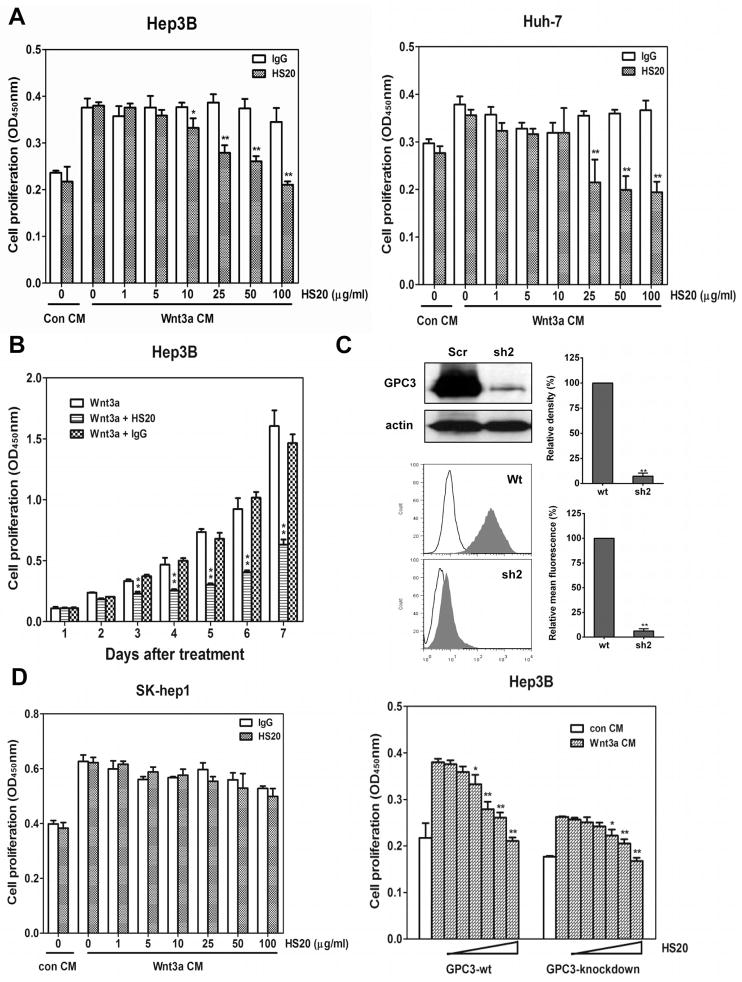

Figure 5. HS20 inhibits Wnt3a-induced cell proliferation.

(A) Cells were starved for 2 hours and then pretreated with 2x indicated concentrations of HS20. One hour later, equal volumes of Wnt3a CM were added. Cells were cultured for 3 days and cell proliferation was measured by WST-8 assay. The data represent the mean ± SD (*p <0.05 and **P <0.01). (B) Hep3B cells were treated with 100 μg/ml of HS20 as described in (A). Cell proliferation was measured on different days by WST-8 assay. The data represent the mean ± SD (**P <0.01). (C) Wild type Hep3B cells and GPC3 knockdown Hep3B cells were treated with increased concentrations of HS20 as described in (A). Cell proliferation was measured by WST-8 assay after 3 days. GPC3 knockdown efficiency was calculated by western blot and flow cytometry. The data represent the mean ± SD (*P <0.05 and **P <0.01). (D) SK-hep1 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml of HS20 as described in (A). Cell proliferation was measured on day 3. The data represent the mean ± SD.

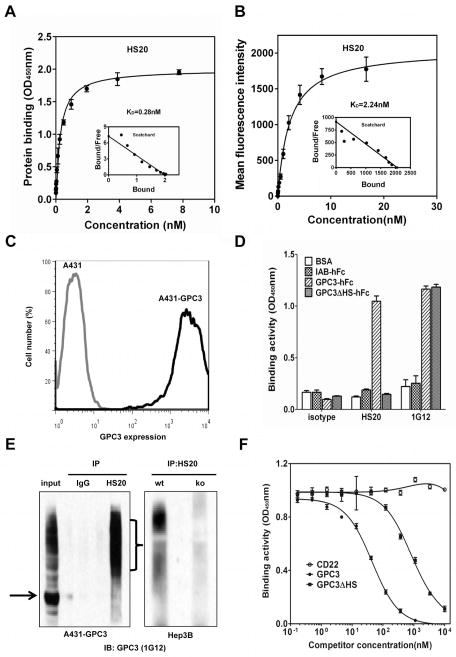

Discovery of a human monoclonal antibody against the HS chains of GPC3

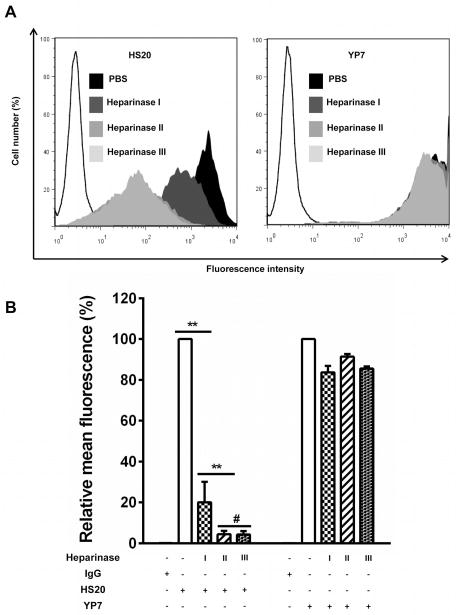

In order to isolate a neutralizing antibody to GPC3, we performed phage display and found several single-chain variable fragment (scFv) clones positively bound to recombinant GPC3 proteins. Among these isolates, clone HS20 was the strongest binder to all of the GPC3 proteins tested in our study (Fig. S1). We converted the HS20 scFv into a human IgG (named HS20) and removed an undesired N-linked glycosylation site in the light chain complementarity determining region (CDR) 2 at position N50 (Fig. S2). The binding affinity of HS20 for GPC3 protein and tumor cells was 0.28 nM and 2.24 nM, respectively (Fig. 2A and 2B), which is similar to the affinity of approved cancer therapeutic antibodies. Flow cytometric analysis of A431 and A431-GPC3 cells showed that HS20 bound A431-GPC3 efficiently but did not bind A431 cells (Fig. 2C). HS20 recognized glycosylated GPC3, but not the GPC3 mutant containing only the protein core (Fig. 2D and Fig. 2E), suggesting that the HS chains of GPC3 may contain a dominant binding site for HS20. However, we could not rule out the possibility that the core protein might also be involved in HS20 binding because we used the whole GPC3 molecule in phage panning. We performed a competitive ELISA where HS20 was pre-incubated with GPC3 or GPC3ΔHS before addition to the GPC3-coated plate. Although GPC3 showed a 20 fold higher binding activity than GPC3ΔHS, they both competed with HS20 (Fig. 2F), indicating that the GPC3 core protein may also contribute to HS20 binding. To further analyze the binding motif of HS20, we removed the HS chains of GPC3 by heparinase digestion. Heparinase I recognizes highly sulfated regions and is specific for heparin. Heparinase II digests both heparin and HS, while heparinase III degrades less-sulfated regions and is more active on HS.31 We found that HS20 cell binding decreased 80% following heparinase I treatment, and both heparinase II and heparinase III treatments led to a 96% decrease in HS20 binding. However, the binding of YP7, a previously described GPC3 core protein-specific antibody,32 did not change after heparinase treatment (Fig. 3). In summary, we isolated a human monoclonal antibody recognizing a distinct HS glycan structure of GPC3 that involves both sulfated and non-sulfated regions of HS.

Figure 2. Isolation of a human antibody targeting HS chains of GPC3.

(A) The binding affinity of HS20 on GPC3-his. (B) The binding affinity of HS20 on A431-GPC3 cells. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of HS20 on A431 and A431-GPC3 cells. (D) Binding properties of HS20 on GPC3, GPC3ΔHS, or irrelevant human Fc protein IAB. 1G12, a commercial mouse antibody against GPC3. (E) Immunoprecipitation of GPC3 in A431-GPC3 cells, Hep3B, and Hep3B GPC3 knockdown cells. Cell lysates incubated with HS20 or human IgG for immunoprecipitation. The immunoprecipitated complex was detected by 1G12. Black arrow indicates the GPC3 core protein and the bracket indicates glycosylated GPC3. Wt: wild type; ko: knockdown. GPC3 knockdown efficiency has been shown in Fig. 5C. (F) Competitive ELISA. Different concentrations of GPC3 or GPC3ΔHS were pre-incubated with HS20 (0.1 nM) for 1 hour. The mixture was added into the GPC3-coated plate to measure the binding of HS20/GPC3. CD22 was used as the negative control. The data represent the mean ± SD.

Figure 3. Both sulfated and non-sulfated regions of HS chain are involved in HS20 binding.

(A) Treatment of GPC3-expressing cells with heparinase I, II and III. A431-GPC3 cells were treated with different heparinases for 2 hours at 37°C. Cells were then stained with HS20 (5 μg/ml) or YP7 (1 μg/ml) for flow cytometry. (B) Statistical analysis of three independent experiments. The binding fluorescence signals of untreated cells represent 100%. The data represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (**P <0.01 and #P > 0.05).

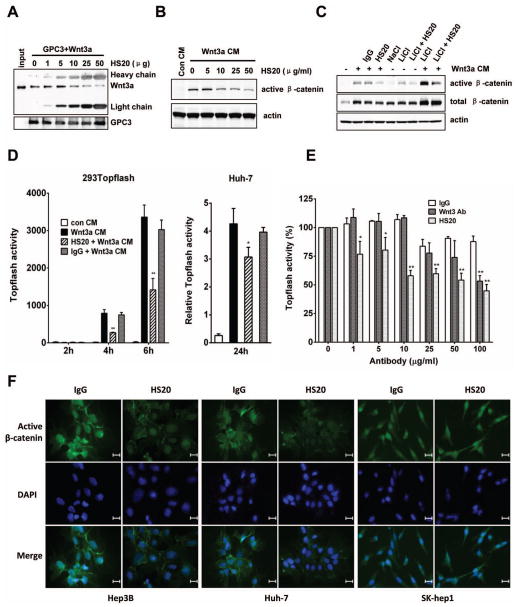

HS20 blocks Wnt activation in vitro

Given that GPC3 was proposed to be a storage site for Wnt, 21 we compared GPC3/Wnt3a interactions with or without HS20 treatment. Pre-incubation of GPC3 with HS20 blocked the Wnt3a-GPC3 interaction in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Treating cells with HS20 significantly blocked Wnt3a-induced accumulation of active β-catenin in HEK293-SuperTopFlash cells. The inhibition occurred in a dose-dependent manner with the amount of active β-catenin reduced by at least 50% after treatment with 10 μg/ml of HS20 (Fig. 4B). We used lithium chloride (LiCl), an inhibitor of GSK3β, as an intracellular activator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. HS20 also blocked LiCl induced β-catenin activation. Interestingly, a combination of LiCl and Wnt3a showed synergistic activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which was also partially blocked by HS20 (Fig. 4C and Fig. S3). The Topflash reporter assay showed that HS20 inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling in both HEK293-SuperTopflash cells and native HCC cells (Huh-7) (Fig. 4D). We also included an anti-Wnt3a commercial antibody as a positive control. Interestingly, compared to the Wnt3a antibody (100μg/ml), HS20 required a lower concentration (10μg/ml) to cause similar inhibition of Topflash activation (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, immunocytofluorescence staining showed that HS20-treated Hep3B and Huh-7 cells had a decreased amount of active β-catenin in nuclei, whereas there was little difference in the nuclear staining of active β-catenin in GPC3-negative SK-hep1 cells treated with HS20 or the control IgG (Fig. 4F). Taken together, our results show that HS20 blocks the interaction of Wnt3a and GPC3 and thereby inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling in vitro.

Figure 4. HS20 blocks Wnt/β-catenin activation.

(A) GPC3-hFc was pre-incubated with different amounts of HS20 for 1 hour on ice and then recombinant Wnt3a was added and incubated for another 2 hours on ice. Protein A-Agarose beads were added to capture the hFc fusion protein. The captured proteins were released with 1x SDS loading buffer. Western blot was performed to detect Wnt3a. (B) HEK293 SuperTopflash cells were starved for 2 hours and then pretreated with 2x indicated concentrations of HS20. An hour later, equal volumes of Wnt3a CM were added. Active β-catenin expression level was detected by Western blot 6 hours later. (C) HEK293 SuperTopFlash cells were starved for 2 hours and then pretreated with or without 200 μg/ml of HS20. One hour later, equal volumes of Wnt3a CM (combined with or without 20 mM LiCl or NaCl) were added. β-catenin expression level was detected 6 hours later. (D) HEK293 SuperTopflash cells or transfected Huh-7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml or 25 ug/ml of HS20 as described in (B). Topflash activity was measured at indicated time points. The data represent the mean ± SD (*P <0.05 and **P <0.01). (E) HEK293 SuperTopflash cells were treated with different concentrations of human IgG, HS20 or anti-Wnt3a antibody as described in (B). Topflash activity was measured after 6 hours. The data represent the mean ± SD (*P <0.05 and **P <0.01). (F) Immunocytofluorescence staining of β-catenin in Hep3B, Huh-7 and SK-hep1 cells. Cells were treated as described in (B). Twenty-four hours later, cells were stained with active β-catenin antibody after fixation. Scale bar, 20 μm.

HS20 inhibits Wnt-dependent cell proliferation

To further determine whether HS20 can neutralize GPC3 function, we tested its ability to disrupt Wnt3a-dependent proliferation of Hep3B and Huh-7 cells (Fig. 5A). HS20 showed significant inhibition with a concentration as low as 25 μg/ml. At least 50% of Wnt3a-induced cell proliferation was blocked after 4 days (Fig. 5B). When we used GPC3 shRNA to decrease expression in Hep3B cells, cells grew slower and were less sensitive to Wnt3a treatment. The cells treated with GPC3 shRNA were still inhibited by HS20, which may be due to the remaining GPC3 after knockdown (around 7%) (Fig. 5C). However, HS20 did not inhibit the proliferation of a GPC3 negative HCC cell line (SK-hep1) (Fig. 5D). These data indicate that HS20 neutralized the mitogenic activity of Wnt3a CM, presumably by blocking the interaction of GPC3 with Wnt3a.

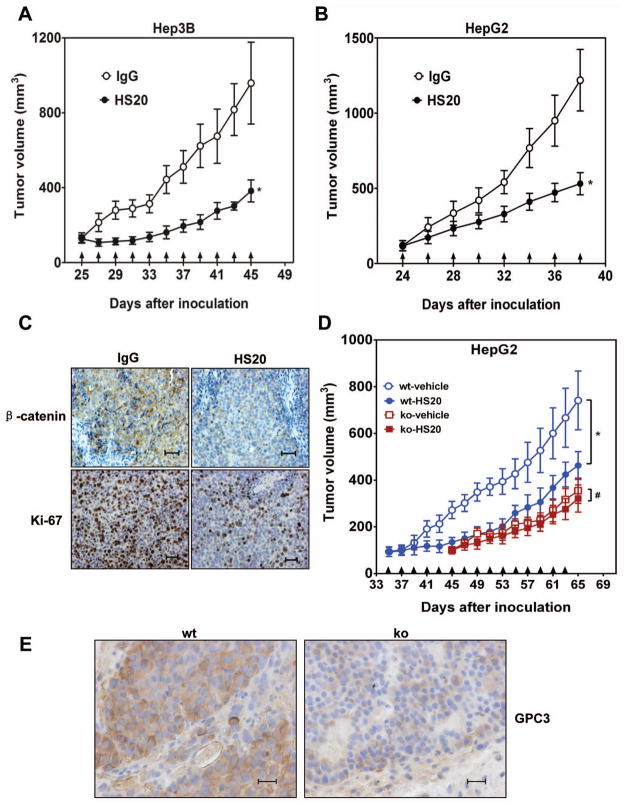

Anti-tumor activity and in vivo toxicity of HS20

To evaluate the antitumor activity of HS20 in animals, we subcutaneously inoculated nude mice with Hep3B or HepG2 cells and then treated the animals with HS20 three times a week. HS20 showed significant anti-tumor activity in both models (Fig. 6A and Fig. 6B). HS20-treated tumors also had less β-catenin staining and contained fewer proliferating cells (Fig. 6C). Moreover, when we inoculated GPC3 knockdown HepG2 cells into mice the tumor grows much slower than wild type xenografts, indicating GPC3 plays a pivotal role for HCC tumor growth. When we treated the GPC3 knockdown xenografts with HS20, tumor growth cannot be inhibited (Fig. 6D and 6E). This observation suggests inhibition of HCC tumor growth by HS20 is GPC3-dependent.

Figure 6. Anti-tumor activity via the HS20 antibody.

BALB/c nu/nu mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 5×106 Hep3B or HepG2 cells (A and B) or 3 × 106 wild type or GPC3 knockdown HepG2 cells (C). When tumors reached an average volume of 100 mm3, mice were intravenously administered 20 mg/kg HS20 three times a week. The arrows indicate HS20 injections. The data represent the mean ± SD (*P <0.05 and #P >0.05).

(A) Hep3B xenografts were treated with HS20 (n=5/group). Human IgG was injected as control. (B) HepG2 xenografts were treated with HS20 (n=7/group). Human IgG was injected as control. (C) β-catenin and Ki-67 immunohistochemistry staining of Hep3B xenografts. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Wild type HepG2 xenografts (n=5/group) and GPC3 knockdown HepG2 xenografts (n=4/group) were treated with HS20. PBS was used as vehicle control. (E) GPC3 expression level in wild type and knockdown xenograft were detected by YP7 staining.

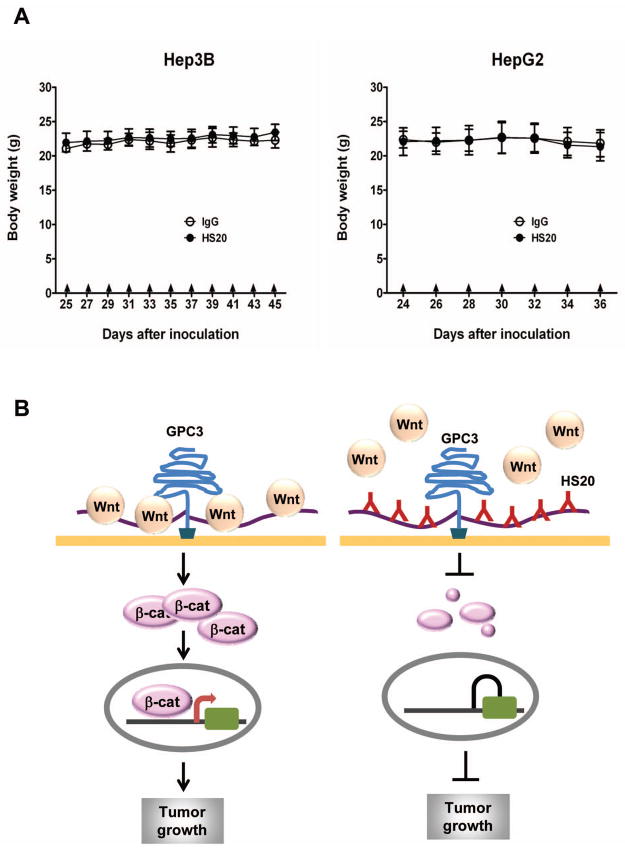

To examine the toxicity of HS20, after mice were treated with the antibody for 16 days, we performed in vivo toxicology studies. HS20 treated-mice did not lose body weight compared to control group (Fig. 7A). All serum chemistry and blood cell counts in the HS20-treated group were similar to those of the control group; the organ weights of HS20 treated-mice were not significantly different from those of the control group mice (Table 1), suggesting HS20 has no detectable in vivo toxicity in mice. Taken together, our results indicated that HS20 had potent anti-tumor activity in HCC xenograft models consistent with its inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Body weight of HS20-treated mice.

(A) Body weight of HS20 treated mice. The data represent the mean ± SD (B) The working model for the mechanistic interaction of HS20 and GPC3. The numbers and locations of Wnt and antibody molecules bound to HS chains of GPC3 were drawn arbitrarily.

Table 1.

Selected Toxicological Results and Organ Weights

| Selected Parameters | Control | HS20 | Normal Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (K/μL) | 7.14 ± 1.11 | 7.14 ± 1.59 | 1.80 – 10.70 |

| Red blood cells (M/μL) | 10.81 ± 0.51 | 9.63 ± 0.82 | 6.36 – 9.42 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.37 ± 0.29 | 3.97 ± 0.32 | 1.6 – 2.8 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 52.67 ± 13.01 | 49.33 ± 3.51 | 67 – 282 |

| Alanie aminotransferase | 50.33 ± 16.17 | 37.67 ± 9.81 | 29 – 181 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 – 0.6 |

| Creatine (mg/dL) | <0.2 | <0.2 | 0.2 – 0.4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 16.73 ± 0.45 | 14.60 ± 1.08 | 11.00 – 15.10 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.97 ± 0.23 | 5.67 ± 0.25 | 4.2 – 5.9 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 16.00 ± 2.65 | 21.67 ± 4.04 | 12 – 52 |

| Selected Organ Weights (mg) | |||

| Brain | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | NA |

| Heart | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | NA |

| Kidney | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | NA |

| Liver | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | NA |

| Lung | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | NA |

| Spleen | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | NA |

| Body weight | 21.48 ± 1.28 | 21.08 ± 0.42 | NA |

Represented toxicological data and organ weights for HepG2 xenografted mice (n = 3/group) treated with HS20 (i.v. every other day, 20 mg/kg). Data represent mean ± SD. NA, not applicable.

Discussion

Oncogenic activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is common in HCC.33 The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is regulated by HSPGs, which may capture Wnt at the cell surface and prevent it from aggregating.34 GPC3 is highly expressed in HCC and has been proposed to function as the storage site for Wnt3a.21 In the present study, we showed that the antibody HS20 had a high affinity for GPC3 and GPC3-positive cells, and inhibited Wnt3a/β-catenin signaling and HCC cell proliferation, apparently by targeting the HS chains of GPC3. These properties make HS20 a unique therapeutic antibody candidate for the treatment of liver cancer.

We demonstrated that HS20 recognized both sulfated and non-sulfated domains in the HS chains of GPC3. Although the crystal structures of Dlp35 in Drosophila and human GPC136 have recently been solved, neither of these structures contained HS. Furthermore, we did not identify any specific hits in the glycan arrays performed by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (unpublished observations). Thus; a more detailed characterization of the binding motif of HS20 is currently not feasible. Considering that previous work showed that GPC3 without HS chains still can form the complex with Wnt, 21 it is possible that HS20 might block Wnt3a/GPC3 interaction via a steric mechanism. As shown in our competitive ELISA assay, both GPC3 and GPC3ΔHS blocked HS20 binding (Fig. 2F). This result suggests that HS20 may recognize a unique binding conformation for Wnt3a, which consists of both HS and the core protein.

HS20 inhibited HCC tumor growth by neutralizing the functions of GPC3. It disturbed GPC3/Wnt3a interactions and blocked Wnt/β-catenin signaling. We compared HS20 with a Wnt3a neutralizing antibody and found that HS20 was effective at concentrations 10-fold lower than the Wnt3a antibody. This observation may indicate that targeting surface-associated GPC3 would be a promising alternative strategy to block Wnt signaling. Moreover, instead of the universal expression of Wnt or FZD molecules, GPC3 is rigorous expressed in HCC. This important property suggests that in HCC, targeting GPC3 would less likely affect normal human adult tissues which do not express cell surface GPC3.

An increasing number of HSPG functions associated with tumor progression validates HS-based treatment for cancer therapy. Currently, there are no approved drugs directed at HS. However, several HS mimetic drugs such as PI-8837–39 and M402 40 show promising results in clinical trials and provide rationale for targeting HS in the treatment of human cancers. Other anti-HS antibodies were generated and most of them were used as research reagents.41–43 A human antibody recognizing the carbohydrate antigen sialyl-Lewis doubled the median survival of mice in a colon carcinoma model.44 However, no antibody candidates that recognize tumor-associated HS are being evaluated in preclinical or clinical studies.

In conclusion, HS20 neutralized Wnt/β-catenin signaling and HCC growth by targeting the HS chains of GPC3, indicating the potential therapeutic anti-tumor activity of this antibody. HS20 may represent a novel class of neutralizing antibodies that could provide mechanistic insight into HSPG function and in particular, the role of HS in Wnt activation. This work also unveils a biologically meaningful rationale for neutralizing HS in tumors that could translate into a novel liver cancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI, Center for Cancer Research (Z01 BC 010891 and ZIA BC 010891) and by the 2011 NCI Director’s Intramural Innovation Award (Principal Investigator Award) to M. Ho.

We appreciate Drs. Xin Wei Wang and David FitzGerald (NCI) for critically reading the manuscript, Zhewei Tang (NCI) for assistance in animal testing, Dr. Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins Medical School, for providing HEK293 SuperTopflash stable cell line, and Dr. Yingzi Yang (NHGRI) for the kind gift of L-cell and L-Wnt3a cell lines. We thank Dr. Miriam Anver, Pathology/Histotechnology Laboratory, SAIC/NCI, for helping with the In vivo toxicity test, immunohistochemistry staining and quantitative analysis. We also thank the NIH Fellows Editorial Board for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HSPGs

heparan sulfate proteoglycans

- GPC3

Glypican-3

- FZD

Frizzled

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HS

heparan sulfate

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- CM

conditioned medium

- MSLN

mesothelin

- scFv

single-chain variable fragment

- LiCl

lithium chloride

- GSK3-β

glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

- CBC

complete blood counts

- CDR

complementarity determining region

Contributor Information

Wei Gao, Email: gaow2@mail.nih.gov.

Heungnam Kim, Email: heungnam87@hotmail.com.

Mingqian Feng, Email: fengm@mail.nih.gov.

Yen Phung, Email: ytphung@gmail.com.

Charles P. Xavier, Email: xaviercp@mail.nih.gov.

Jeffrey S. Rubin, Email: rubinj@mail.nih.gov.

Mitchell Ho, Email: homi@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Ho M, Kim H. Glypican-3: a new target for cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengochea A, de Souza MM, Lefrancois L, Le Roux E, Galy O, Chemin I, Kim M, et al. Common dysregulation of Wnt/Frizzled receptor elements in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:143–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei W, Chua MS, Grepper S, So SK. Blockade of Wnt-1 signaling leads to anti-tumor effects in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:76. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.You XJ, Bryant PJ, Jurnak F, Holcombe RF. Expression of Wnt pathway components frizzled and disheveled in colon cancer arising in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:691–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurney A, Axelrod F, Bond CJ, Cain J, Chartier C, Donigan L, Fischer M, et al. Wnt pathway inhibition via the targeting of Frizzled receptors results in decreased growth and tumorigenicity of human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11717–11722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120068109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeAlmeida VI, Miao L, Ernst JA, Koeppen H, Polakis P, Rubinfeld B. The soluble wnt receptor Frizzled8CRD-hFc inhibits the growth of teratocarcinomas in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5371–5379. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei W, Chua MS, Grepper S, So SK. Soluble Frizzled-7 receptor inhibits Wnt signaling and sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells towards doxorubicin. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nambotin SB, Wands JR, Kim M. Points of therapeutic intervention along the Wnt signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:549–559. doi: 10.2174/187152011796011019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettenberg SA, Charlat O, Daley MP, Liu S, Vincent KJ, Stuart DD, Schuller AG, et al. Inhibition of tumorigenesis driven by different Wnt proteins requires blockade of distinct ligand-binding regions by LRP6 antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15473–15478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007428107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasisekharan R, Shriver Z, Venkataraman G, Narayanasami U. Roles of heparan-sulphate glycosaminoglycans in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:521–528. doi: 10.1038/nrc842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, Zako M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bishop JR, Schuksz M, Esko JD. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature. 2007;446:1030–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature05817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindahl U, Li JP. Interactions between heparan sulfate and proteins-design and functional implications. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;276:105–159. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)76003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filmus J, Capurro M, Rast J. Glypicans. Genome Biol. 2008;9:224. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu HC, Cheng W, Lai PL. Cloning and expression of a developmentally regulated transcript MXR7 in hepatocellular carcinoma: biological significance and temporospatial distribution. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5179–5184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirakawa H, Suzuki H, Shimomura M, Kojima M, Gotohda N, Takahashi S, Nakagohri T, et al. Glypican-3 expression is correlated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1403–1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun CK, Chua MS, He J, So SK. Suppression of glypican 3 inhibits growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through up-regulation of TGF-beta2. Neoplasia. 2011;13:735–747. doi: 10.1593/neo.11664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruan J, Liu F, Chen X, Zhao P, Su N, Xie G, Chen J, et al. Inhibition of glypican-3 expression via RNA interference influences the growth and invasive ability of the MHCC97-H human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Int J Mol Med. 2011;28:497–503. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Li Y, Chen W, Zheng P, Liu T, He W, Zhang J, et al. Silencing glypican-3 expression induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;419:656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang N, Lin J, Ruan J, Su N, Qing R, Liu F, He B, et al. MiR-219-5p inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation by targeting glypican-3. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:884–891. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capurro MI, Xiang YY, Lobe C, Filmus J. Glypican-3 promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating canonical Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6245–6254. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zittermann SI, Capurro MI, Shi W, Filmus J. Soluble glypican 3 inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1291–1301. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng M, Kim H, Phung Y, Ho M. Recombinant soluble glypican 3 protein inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2246–2247. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishiguro T, Sugimoto M, Kinoshita Y, Miyazaki Y, Nakano K, Tsunoda H, Sugo I, et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibody as a potential antitumor agent for human liver cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9832–9838. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu AX, Gold PJ, El-Khoueiry AB, Abrams TA, Morikawa H, Ohishi N, Ohtomo T, et al. First-in-Man Phase I Study of GC33, a Novel Recombinant Humanized Antibody Against Glypican-3, in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:920–928. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng M, Gao W, Wang R, Chen W, Man YG, Figg WD, Wang XW, et al. Therapeutically targeting glypican-3 via a conformation-specific single-domain antibody in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217868110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Q, Wang Y, Dabdoub A, Smallwood PM, Williams J, Woods C, Kelley MW, et al. Vascular development in the retina and inner ear: control by Norrin and Frizzled-4, a high-affinity ligand-receptor pair. Cell. 2004;116:883–895. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Endo Y, Wolf V, Muraiso K, Kamijo K, Soon L, Uren A, Barshishat-Kupper M, et al. Wnt-3a-dependent cell motility involves RhoA activation and is specifically regulated by dishevelled-2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:777–786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Wildt RM, Tomlinson IM, van Venrooij WJ, Winter G, Hoet RM. Comparable heavy and light chain pairings in normal and systemic lupus erythematosus IgG(+) B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:254–261. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<254::AID-IMMU254>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho M, Feng M, Fisher RJ, Rader C, Pastan I. A novel high-affinity human monoclonal antibody to mesothelin. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2020–2030. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rozenberg GI, Espada J, de Cidre LL, Eijan AM, Calvo JC, Bertolesi GE. Heparan sulfate, heparin, and heparinase activity detection on polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using the fluorochrome tris(2,2′-bipyridine) ruthenium (II) Electrophoresis. 2001;22:3–11. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200101)22:1<3::AID-ELPS3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phung Y, Gao W, Man YG, Nagata S, Ho M. High-affinity monoclonal antibodies to cell surface tumor antigen glypican-3 generated through a combination of peptide immunization and flow cytometry screening. MAbs. 2012;4:592–599. doi: 10.4161/mabs.20933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee HC, Kim M, Wands JR. Wnt/Frizzled signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Biosci. 2006;11:1901–1915. doi: 10.2741/1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuerer C, Habib SJ, Nusse R. A study on the interactions between heparan sulfate proteoglycans and Wnt proteins. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:184–190. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim MS, Saunders AM, Hamaoka BY, Beachy PA, Leahy DJ. Structure of the protein core of the glypican Dally-like and localization of a region important for hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13112–13117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109877108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svensson G, Awad W, Hakansson M, Mani K, Logan DT. Crystal structure of N-glycosylated human glypican-1 core protein: structure of two loops evolutionarily conserved in vertebrate glypican-1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:14040–14051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parish CR, Freeman C, Brown KJ, Francis DJ, Cowden WB. Identification of sulfated oligosaccharide-based inhibitors of tumor growth and metastasis using novel in vitro assays for angiogenesis and heparanase activity. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3433–3441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kudchadkar R, Gonzalez R, Lewis KD. PI-88: a novel inhibitor of angiogenesis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1769–1776. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.11.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferro V, Dredge K, Liu L, Hammond E, Bytheway I, Li C, Johnstone K, et al. PI-88 and novel heparan sulfate mimetics inhibit angiogenesis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2007;33:557–568. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-982088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou H, Roy S, Cochran E, Zouaoui R, Chu CL, Duffner J, Zhao G, et al. M402, a novel heparan sulfate mimetic, targets multiple pathways implicated in tumor progression and metastasis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Born J, Salmivirta K, Henttinen T, Ostman N, Ishimaru T, Miyaura S, Yoshida K, et al. Novel heparan sulfate structures revealed by monoclonal antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20516–20523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruinsma IB, te Riet L, Gevers T, ten Dam GB, van Kuppevelt TH, David G, Kusters B, et al. Sulfation of heparan sulfate associated with amyloid-beta plaques in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wittrup A, Zhang SH, ten Dam GB, van Kuppevelt TH, Bengtson P, Johansson M, Welch J, et al. ScFv antibody-induced translocation of cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan to endocytic vesicles: evidence for heparan sulfate epitope specificity and role of both syndecan and glypican. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32959–32967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sawada R, Sun SM, Wu X, Hong F, Ragupathi G, Livingston PO, Scholz WW. Human monoclonal antibodies to sialyl-Lewis (CA19. 9) with potent CDC, ADCC, and antitumor activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1024–1032. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.