Abstract

Background

Data regarding the prescription status of individuals with diabetes are limited. This study was an analysis of participants from the relationship between cardiovascular disease and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in patients with type 2 diabetes (REBOUND) Study, which was a prospective multicenter cohort study recruited from eight general hospitals in Busan, Korea. We performed this study to investigate the current status of prescription in Korean type 2 diabetic patients.

Methods

Type 2 diabetic patients aged 30 years or more were recruited and data were collected for demographics, medical history, medications, blood pressure, and laboratory tests.

Results

Three thousands and fifty-eight type 2 diabetic patients were recruited. Mean age, duration of diabetes, and HbA1c were 59 years, 7.6 years, and 7.2%, respectively. Prevalence of hypertension was 66%. Overall, 7.3% of patients were treated with diet and exercise only, 68.2% with oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs) only, 5.3% with insulin only, and 19.2% with both insulin and OHA. The percentage of patients using antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, antiplatelet agents was similar as about 60%. The prevalence of statins and aspirin users was 52% and 32%, respectively.

Conclusion

In our study, two thirds of type 2 diabetic patients were treated with OHA only, and one fifth with insulin plus OHA, and 5% with insulin only. More than half of the patients were using each of antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, or antiplatelet agents. About a half of the patients were treated with statins and one third were treated with aspirin.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, type 2; Drug therapy; Hospitals, general

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a disease whose prevalence is increasing exponentially worldwide, causing serious socioeconomic and health issues. The prevalence of diabetes in those aged 30 years or more in Korea was merely 1.5% according to a cohort study in 1971, but the prevalence increased to 7.2% by a cohort study in Yonchon County in 1993, and again to 8.9% as reported by the National Health and Nutrient Survey in 2001 [1,2]. Despite taking into account the regional difference or the change of standard diagnostic criteria of diabetes, the prevalence increased by ~5-fold during the previous 30 years. In addition, diabetic complications including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), blindness, end-stage renal disease, lower limb amputation, etc., have constantly increased, leading to higher medical expenses, hospitalization, and even death [1,2].

Uncertainties regarding the benefits of intensive glycemic control on macrovascular complications from results of a series of recent large scale research have changed from the original strategy, concentrating on aggressive glucose control, to new strategy, considering the individual patient characteristics such as age and comorbidities [3,4]. The treatment protocols for type 2 diabetes continue to become complicated, following the development of new pharmacologic agents. The Korean Diabetes Association have been establishing a clinical practice guidelines for type 2 diabetes ever since 1990, which have been revised for the fourth time in 2011 [5], and the insurance payment guidelines for antidiabetic drugs were newly announced in July 2011. Prescription patterns of clinicians is predicted to change immensely depending on the revision of treatment guidelines for diabetes and insurance guidelines for antidiabetic drugs. However, clinical data regarding the current status of prescription in type 2 diabetic patients remains rare [6].

The relationship between cardiovascular disease and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in patients with type 2 diabetes (REBOUND) is a study comparing and analyzing the differences in the prevalence of CVDs according to the brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity, of type 2 diabetic patients aged 30 years or more from eight general hospitals in Busan. Here, we have investigated the current status of prescription in type 2 diabetic patients that are being treated in general hospitals in Busan by analyzing the data from the first visit of the REBOUND study.

METHODS

Patients

Type 2 diabetic patients aged 30 years or more who were undergoing treatment at the division of Endocrinology and Metabolism in eight general hospitals in Busan (Bong Seng Hospital, Busan St. Mary's Hospital, Daedong Hospital, Ilsin Hospital, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Maryknoll Hospital, Moonhwa Hospital, and Pusan National University Hospital) were recruited from June 2008 to December 2010. Those who absolutely required insulin treatment and had medical history of ketoacidosis were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each hospital and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection and laboratory tests

Age, sex, duration of diabetes, smoking history, medical history, and current medical status were investigated through interviews and medical records. The patients were divided into current smokers and nonsmokers according to their smoking history. Medical history of retinopathy and CVD was investigated.

Treatment modalities of diabetes, the number of classes and combination types of antihyperglycemic, antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, and antiplatelet agents were investigated. Treatment modalities of diabetes were divided into diet only, oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs) alone, insulin alone, and a combination of insulin and OHA. As for the OHA alone group, patients were divided into four groups according to the number of OHA classes, and were further divided according to combination types of OHA classes within each group. The patients in both insulin and OHA group were also investigated in the same way after dividing into three groups.

Height, weight, and waist circumference of the patients were measured, and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and systolic blood pressures (SBP) were measured at a stable state. The waist circumference was measured from the middle point between the lower line of bottom rib and upper line of the iliac crest. Their body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the height in square meters. The anthropometric measurement of the patients was done using standardized instruments with their coat and shoes off and the blood pressure was measured using a standardized automated sphygmomanometer. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥25 kg/m2, and hypertension was defined as SBP of at least 140 mm Hg or DBP of at least 80 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medications.

The subjects were fasted for at least 8 hours before measuring their fasting glucose level, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), serum lipid, serum insulin, C-peptide, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transferase, serum and urine creatinine, and urine microalbumin. If there were no measured low density lipoprotein (LDL-C) value available, an estimated value (LDL-C=total cholesterol-[triglycerides/5]-HDL-C) was used for patients with triglyceride <4.5 mmol/L, while the value of those with triglyceride level ≥4.5 mmol/L was handled as a 'missing value' [7].

The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated by using the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) formula.

The MDRD fomula: GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)=175×serum Cr (mg/dL)-1.154×age (year-old)-0.203×1.212 (if patient is black)×0.742 (if female).

The microalbuminuria index was obtained from the ratio of microalbuminuria level (µg) and urine creatinine level (µg) of the spot urine sample. The prevalence of retinopathy, and CVD was investigated based on medical history. Microalbuminuria and overt proteinuria were defined as random urine albumin creatinine ratio between 30 and 300 µg/mr Cr, and above 300 µg/mg Cr, respectively. Chronic kidney disease was defined as GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as median values (interquartile range), while stochastic variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. Patient data entry and arrangement were performed using Microsoft Access version 2007 (Microsoft, St. Redmond, WA, USA). Student t-test wase used for continuous variables and either Fisher exact test or chi-square test for categoric variables. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistics software version 3.0.0 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) [8]. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The histogram for the diabetes duration revealed that it was not normally distributed, but skewed. Thus, we used median value instead of the mean value as the representative value of variables.

RESULTS

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study population

Table 1 shows the basal characteristic of the study population. In this analysis, 3,058 patients were included, and 57% (1,745 patients) of them were women. The median age was 59 years; 56 years in men and 62 years in women, showing that women were older. The median BMI was 24.7 kg/m2, with 24.5 kg/m2 in men and 25.0 kg/m2 in women. The prevalence of obesity was 45%; 41% in men and 48% in women. The median waist circumference was 89.5 cm in men and 88.0 cm in women. The median diabetes duration was 7.6 years; 7.0 years in men, and 8.0 years in women, showing that women had slight longer disease duration. 19% (494), 23% (637), 7% (213), 22% (648), and 6.5% (173 patients) had retinopathy, microalbuminuria, overt proteinuria, chronic renal diseases, and CVD, respectively. The median HbA1c level was 7.2%, and there was no significant difference between men and women. The prevalence of hypertension was 66%; 65% in men and 67% in women.

Table 1.

Basal characteristics of study subjects

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular diseases; FPG, fasting plasma sugar; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Prescription status of drug therapy for glucose control

Of the patients, 7.3% (222 patients) were treated with diet only, 68.2% (2,086 patients) with OHA alone, 5.3% (162 patients) with insulin alone, and 19.2% (588 patients) with a combination of insulin and OHA (Table 2). OHA alone therapy was the most prevalent, and insulin therapy was used by 24.5% of the patients. As for the OHA alone therapy, the proportion of the patients in OHA 1, 2, 3, and 4 groups was 19.2% (587 patients), 33.5% (1,025 patients), 15% (460 patients), and 0.5% (14 patients), respectively, showing that approximately half of these patients were using two OHA (Table 2). As for the combination therapy of insulin and OHA, the proportion of the patients in OHA 1, 2, and 3 group was 11.9% (365 patients), 6.1% (188 patients), and 1.1% (35 patients), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prescription status of therapy for diabetes

OHA, oral hypoglycemic agent.

Regarding OHA alone therapy, the most frequently used OHA class in OHA 1 group was metformin (Met), which comprised 76%, followed by sulfonylurea (SU) with 17%, α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGI) with 5%, meglitinides with 2%, and thiazolidinediones (TZD) with 0.7% (Table 3). Of the patients in OHA 2 group, Met+SU combination was used most frequently (43%), followed by Met+dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP4I), Met+TZD, SU+AGI, and SU+TZD combination, which comprised 24%, 14%, 6%, and 5%, respectively (Table 3). Of the patients in OHA 3 group, both Met+SU+TZD and Met+SU+AGI combination was similarly prevalent, as 40% (Table 3). Met was being used by 90% of the patients using OHA alone therapy as single or combination therapy.

Table 3.

Prescription status of therapy for diabetes in patient using oral hypoglycemic agent only

OHA, oral hypoglycemic agent; Met, metformin; SU, sulfonylurea; AGI, α-glucosidase inhibitor; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; Glinide, meglitinide; TZD, thiazolidinedione; DPP4I, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor.

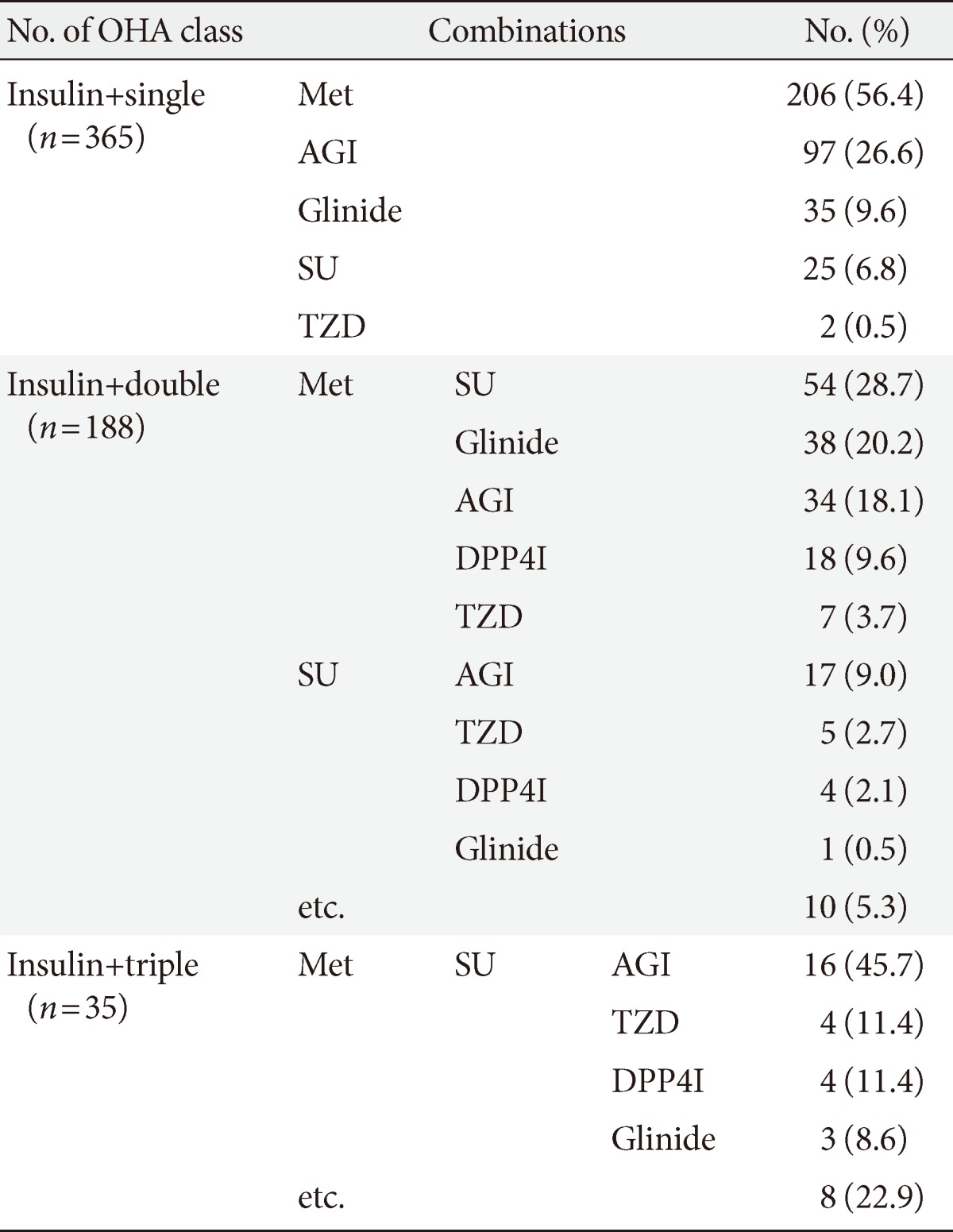

Regarding combination therapy of insulin and OHA, most patients were in OHA 1 or 2 groups. Of the patients in insulin and OHA 1 group, Met was used most frequently by 56%, followed by AGI, meglitinide, and SU, which comprised 27%, 10%, and 7%, respectively. Of the patients in insulin and OHA 2 group, the most popular combination was Met+SU by 29%, followed by Met+meglitinide, Met+AGI, Met and DPP4I, SU and AGI combination, by 20%, 18%, 10%, and 9%, respectively (Table 4). Finally, of the patients in insulin and OHA 3 group, Met+SU+AGI combination was used most frequently by 45.7%, followed by Met+SU+TZD and Met+SU+DPP4I combination, each was used by 11% (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prescription status of therapy for diabetes in patients using insulin and oral hypoglycemic agent

OHA, oral hypoglycemic agent; Met, metformin; AGI, α-glucosidase inhibitor; Glinide, meglitinide; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione; DPP4I, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor.

Prescription status of antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, and antiplatelet agents

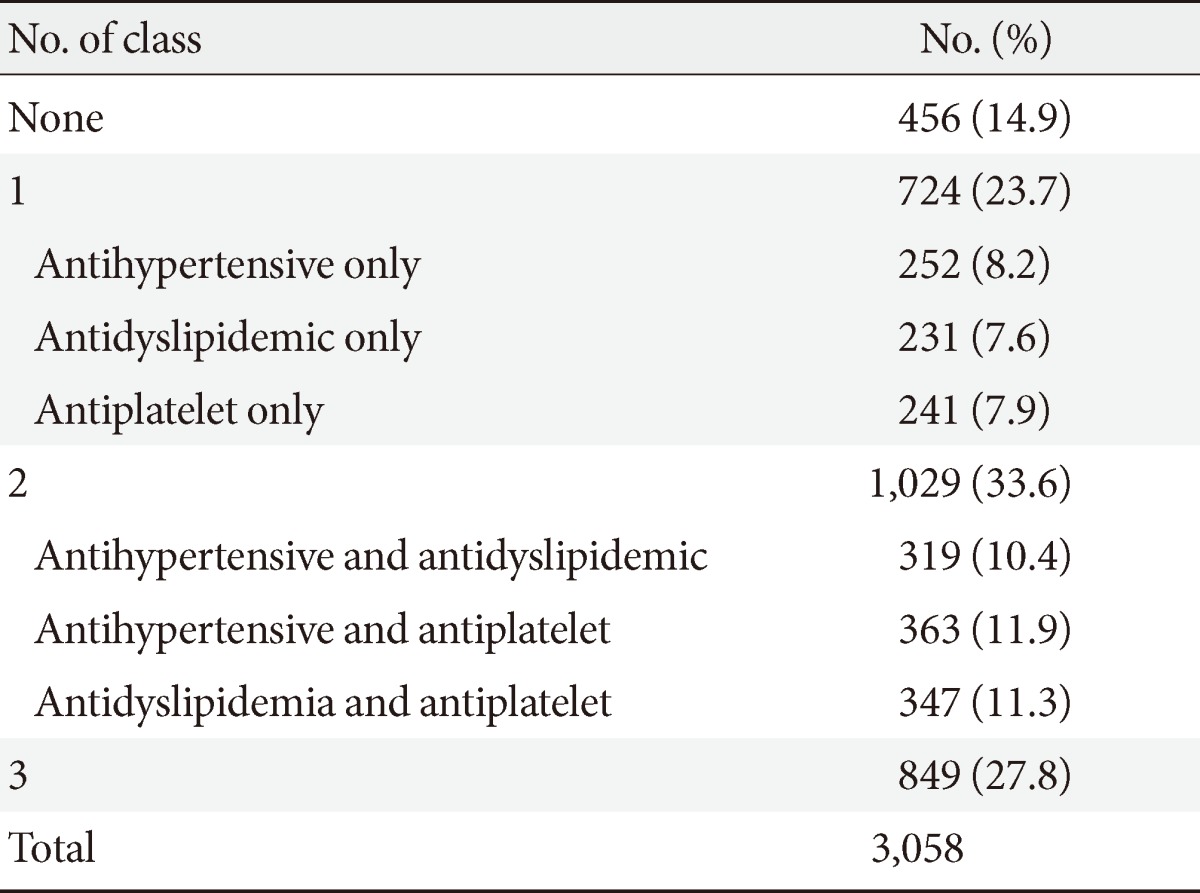

Of the patients, 15% were not treated with any of antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, or antiplatelet agents, 8% were treated with each of three agents only, 10% with both antihypertensive and antidyslipidemic agents, 12% with both antihypertensive and antiplatelet agents, 12% with both antidyslipidemic and antiplatelet agents, and 28% with all three agents (Table 5). The proportion of patients using each of antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, or antiplatelet agents either individually or as a combination was 58% to 59%, which was fairly similar.

Table 5.

Prescription status of antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, and antiplatelet agents

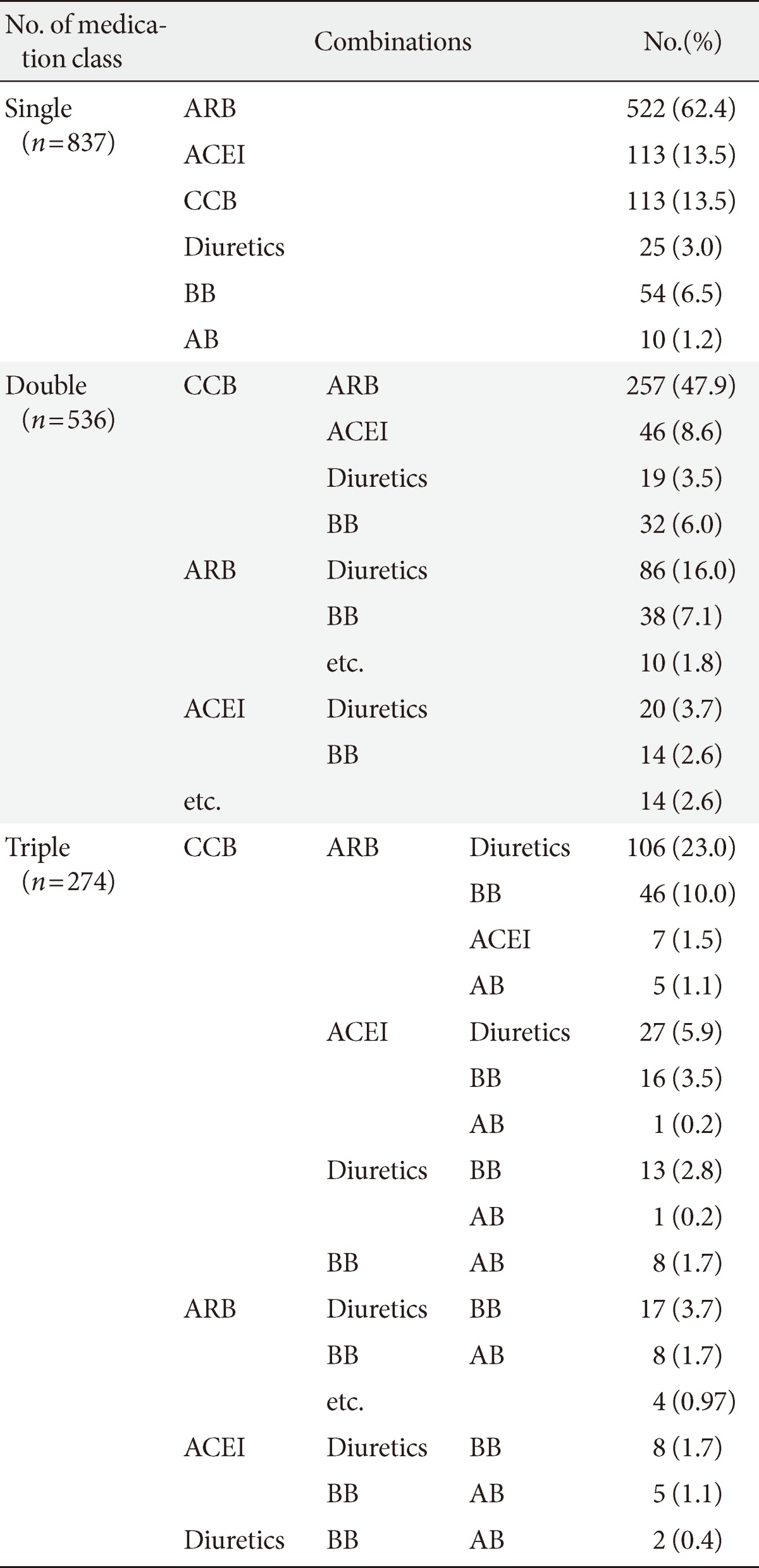

Regarding antihypertensive therapy, 48% were treated with single class, 30.4% with two classes, 16% with three classes, 5% with four classes, 1.2% with five classes, and 0.2% with six classes. Of the patients with single class, 62% was using angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), which was the most popular, followed by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), diuretics, β-blockers (BBs), and α-blockers (ABs), which comprised 13.5%, 13.5%, 3%, 6.5%, and 1.2%, respectively (Table 6). Of the patients with two classes, ARB+CCB combination was used most popularly by 48%, followed by ARB+diuretics, ACEI+CCB, ARB+BB, CCB+BB, and ACEI+diuretics, which comprised 16%, 9%, 7%, 6%, and 4%, respectively (Table 6). Finally, CCB+ARB+diuretics combination was most popular of the classes group, which was used by 23% (Table 6).

Table 6.

Prescription status of antihypertensive agents

ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; CCB, calcium channel blocker; BB, β-blocker; AB, α-blocker.

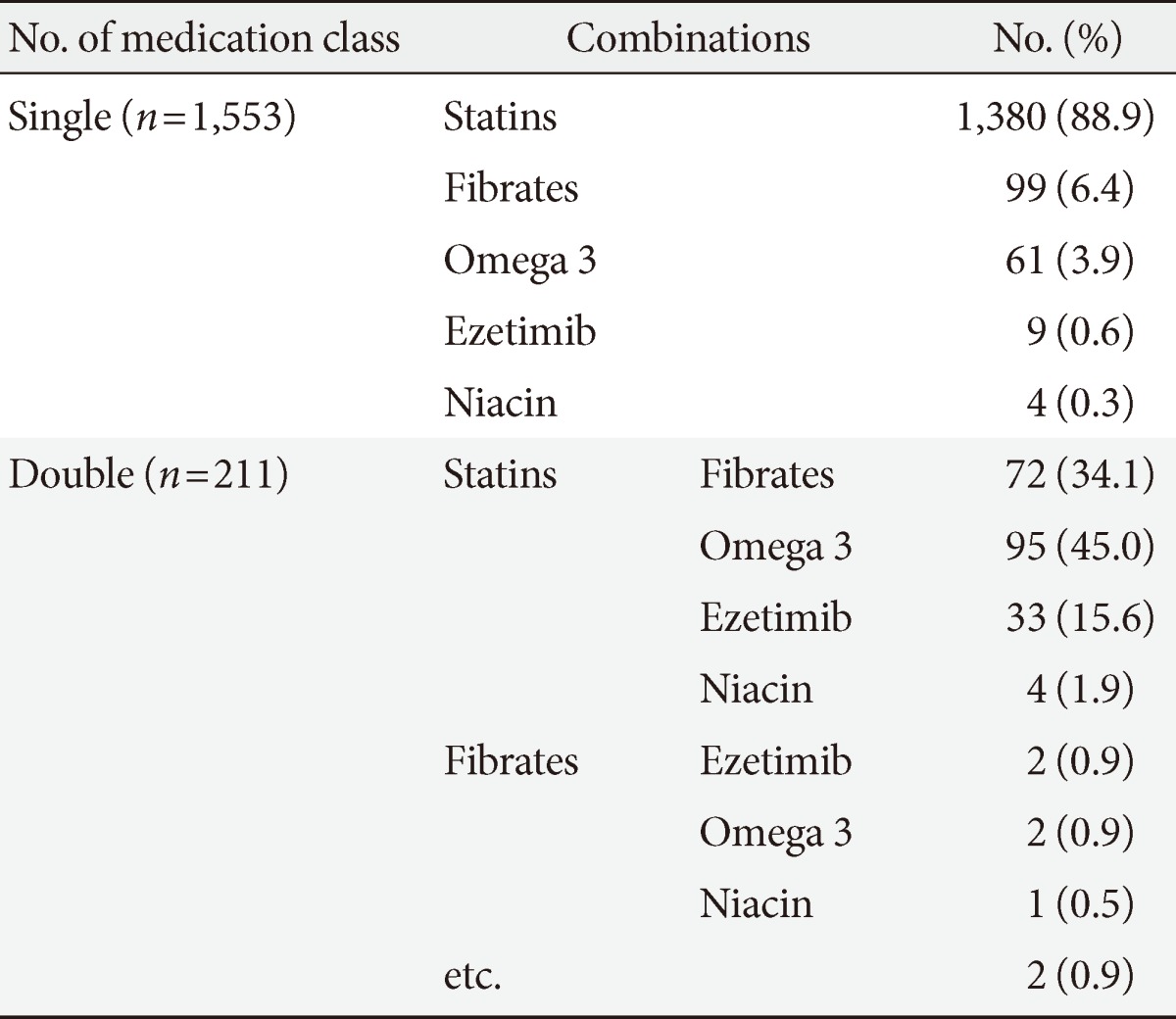

Regarding antidyslipidemic therapy, most patients (88%) were treated with single class, 12% with two classes, and 0.1% with three classes. Of the patients with single class, statins was most popularly used by 89%, followed by fibrates, omega-3 fatty acid, ezetimibe, and niacin, used by 6%, 4%, 0.6%, and 0.3%, respectively (Table 7). Of the patients with two classes, statins+omega-3 fatty acid, statins+fibrates, statins+ezetimib, and statins+niacin combinations were used by 45%, 34%, 17%, and 2%, respectively (Table 7). The 52% of the total patients were using statins in single or combination.

Table 7.

Prescription status of antidyslipidemic agents

Omega 3, omega-3 fatty acid.

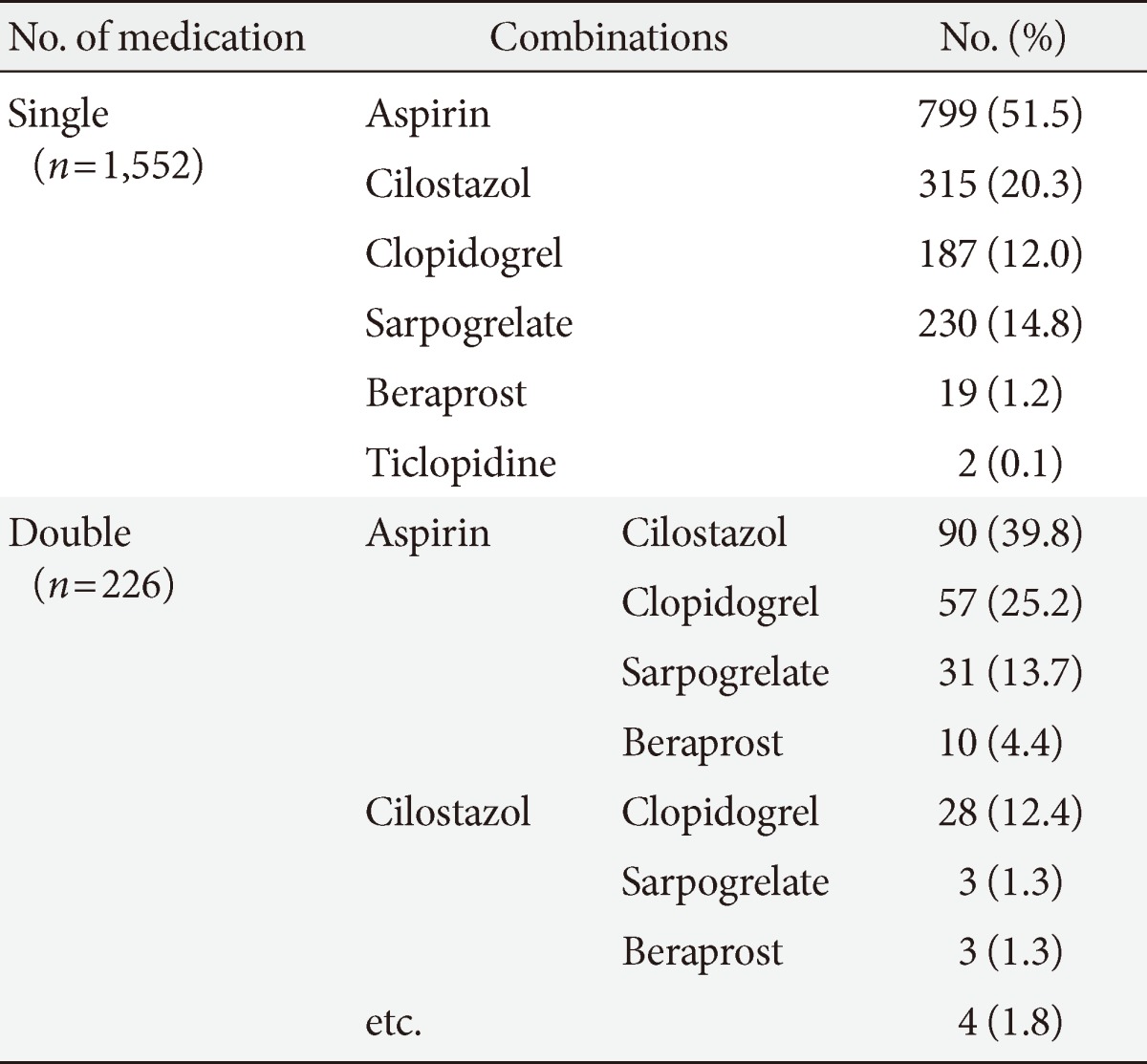

Regarding antiplatelet therapy, most patients (86%) were treated with single agent, 13% with two agents, and 1% with three agents, and 0.1% with four agents. Of the patients with single agent, aspirin was used most frequently by 52%, followed by cilostazol, clopidogrel, sarpogrelate, beraprost, and ticlopidine, which were used by 20%, 12%, 15%, 1.2%, and 0.1%, respectively (Table 8). Of the patients with two agents, aspirin+cilostazol combination was most frequently used by 40%, followed by aspirin+clopidogrel, aspirin+sarpogrelate, and aspirin+beraprost, used by 25%, 14%, and 4%, respectively (Table 8). The 32% of the total patients were using aspirin in single or combination.

Table 8.

Prescription status of antiplatelet agents

DISCUSSION

General characteristics such as age, BMI, waist circumference, etc. and the fact that women tended to be older was similar to previous studies in Korea [9]. However, HbA1c levels were lower but the prevalence of obesity was higher compared to previous reports [9]. The prevalence of hypertension of our study was 66%, which was higher than the health insurance data from 2007 (51% in men 58% in women [9]), but it was similar to another study performed in 2006 by the Department of Endocrinology of the tertiary hospitals in Korea who reported 60.4% prevalence of hypertension [10]. The prevalence of hypertension in diabetic patients varied between each study depending on age, diabetes period, and the definition of hypertension. In our study, hypertension was defined by the usage of any antihypertensive agents or systolic pressure >140 mm Hg or diastolic pressure >90 mm Hg at stable state at the time of initial investigation. The prevalence of hypertension was higher in women, which might be derived from higher age and longer diabetes duration in women. Analysis of the health insurance data from 2007 also showed similar sexual difference in prevalence of hypertension (51% in males and 58% in females).

Our study showed a fairly low prevalence of diabetic complications, which was 19%, 23.1%, 7%, 22%, and 6.5% for retinopathy, microalbuminuria, overt proteinuria, chronic renal diseases, and CVDs [10]. The prevalence of retinopathy and CVDs might be largely underestimated because the definition is vague, based on the medical history rather than objective examinations, and from a number of missing values. We expect that the prevalence of cardiovascular or renal complications to be underestimated as well due to selection bias, as there is a large chance of patients being excluded during recruitment if they were receiving treatment from the Department of Nephrology, Cardiology, or Neurology. Since this study was not aimed at investigating the prevalence of complications, and the definition of neuropathy is uncertain, we did not investigate the prevalence of neuropathy. However, because there is a possibility that relatively small proportion of patients with complications were recruited and large proportion of highly compliant patients were included, we need to be cautious to interpret. According to a health insurance data results by the national sample survey reported in 2007, limited regarding complications of diabetes (about 30% of all patients) showed that 15% were positive with the standard of proteinuria 1+ or more [9]. In a previous study with 5,652 diabetic patients from the Department of Endocrinology of 13 different tertiary hospitals in Korea in 2006, the prevalence of microalbuminruia, retinopathy, neuropathy, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and peripheral vascular diseases were 30.4%, 38.3%, 44.6%, 8.7%, 6.7%, and 3%, respectively [10].

In our study, the most popular therapeutic options of antihyperglycemic therapy was OHA alone, which was used by 68% of patients. According to the health insurance data by the national survey reported in 2007, proportion of patients taking OHA only, insulin only, both insulin and OHA, and diet therapy only was 70%, 4%, 10%, and 16%, respectively [9]. The proportion of patients taking OHA only was similar to our study, but the proportion of insulin therapy was higher, and that of diet therapy was lower in our study. Such a difference may be derived from the fact that the present study was performed in general hospitals not a nationwide survey. According to an American national health and nutrition survey that was done from 2003 to 2006, 18% were treated with diet only, 14% with insulin alone, 57% with OHA alone, and 12% with both insulin and OHA, of which the proportion of insulin alone therapy was higher than the present study [11].

Following the revision of the guidelines from the American Diabetes Association in 2010, a fourth revision was announced in 2011 and the insurance payment criteria for diabetic drugs have also changed accordingly in July, 2007 [5]. In the revised criteria, Met was emphasized to be used primarily as an OHA only treatment method, HbA1c level was to be considered when increasing the quantity of OHA or choosing combination methods, and an insurance payment criteria included for patients using three OHA [5]. In the original guideline, any combinations other than Met, SU, and AGI combination were not admitted as a treatment method using three OHA, but now any three OHA combinations including TZD or DPP4I is accepted as well as taking insulin with Met and SU as a combination. Some combinations are strictly specified to be disallowed, which are SU and meglitinides, AGI and TZD, meglitinides and DPP4I, and AGI and DPP4I combinations [5]. Patients were recruited from June 2008 to December 2010 for this study, which was before the insurance payment criteria revision, but Met was already popularly used, by 90% as an OHA only method and 70% of both insulin and OHA therapy. Furthermore, the previously specified combinations to be disallowed were very rarely used, by 0.9%.

Over 85% of all patients used one or more of antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, and antiplatelet agents, and the proportion of patients taking each of these three agents either individually or in combination were each 58% to 59%, which are all very similar, and 28% used all three together. From this we can see that not only glycemic control but also the usage of antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, and antiplatelet agents are carefully considered for diabetic patients.

Here, the proportion of patients using 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more classes of antihypertensive agents were 47.5%, 30.4%, 15.6%, and 6.5%, respectively. According to a study with patients being treated in the divison of Endocrinology and Metabolism of 13 different tertiary hospitals in Korea in 2006, the proportion of patients using 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more classes of antihypertensive agents was 65%, 25%, 7%, and 3%, respectively, showing that the prevalence of combination therapy has increased over time [10]. Although it is difficult to compare the proportion of specific classes of antihypertensive agents due to the large proportion of combination therapy, it seems that ARB usage has decreased while that of CCB and diuretics has increased. We suspect that the proportion of combination therapy has been increased because of the increased awareness for the importance of tight BP control in type 2 diabetic patients and launching of various new combination drugs of antihypertensives, leading to increased market share. ARB was the most commonly used class of antihypertensive agents, and followed CCB, diuretics, BB, ACEI, and AB, in the order of frequency. ARB or ACEI was used by one third of all patients. ARB was singularly used by 17% of all patients, and ACEI was singularly used by 4% of all patients, which, for this case, some patients might have used these drugs for the treatment of either microalbuminuria or overt proteinuria. However it is mostly difficult to distinguish them in the clinics, so all patients using ARB or ACEI were regarded as having hypertension in this study.

Traditionally, diabetic patients were recommended to take low dose aspirin by most guidelines for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events, but recent large clinical trials and several meta-analyses have failed to show primary preventive effect of CVD in diabetic patients, raising doubts about their efficacy [12,13,14]. Following these reports, the American Diabetes Association have revised their guidelines to recommend aspirin for primary prevention in diabetic patients who are at increased CVD risk (10-year risk of CVD events >10%) and who are not at increased risk for bleeding [15]. In our study, 59% of patients with type 2 diabetes were using antiplatelet agents, and half of them were using aspirin and 80% of these patients were using aspirin singularly. In 2006, an analysis report of the health insurance data was announced, which investigated aspirin usage in newly diagnosed diabetic patients aged 40 years or more from 2001 to 2003, and showed a gradual increase in the proportion of aspirin user, as 6.9% in 2001, 8.9% in 2002, and 11.6% in 2003 [16]. Though direct comparison between two studies is difficult due to the difference in the study design and population, it seems that the usage of aspirin has increased over time, But, considering that our study were subjected at data from before the American Diabetes Association guideline revision in 2010, we expect that the proportion of aspirin user would be decreasing in future studies. With insufficient evidence for primary preventive effects of aspirin and concerns about safety of aspirin in diabetic patients, interests in other antiplatelet agents or antiplatelet combination therapy has increased. But revised insurance guidelines in 2010 still recommends to preferentially use aspirin while restricting the use of other antiplatelet agents only in high-risk patients or if aspirin cannot be used. As far as we are aware, no studies have been presented regarding the prescription status of antiplatelet agents other than aspirin. In our study, the next most frequently used antiplatelet agent after aspirin was cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase III inhibitor, which counted for 20% of antiplatelet monotherapy. The third was sarpogrelate, a serotonin 2A receptor inhibitor, was more frequently used than clopidogrel. Although sarpogrelate has a limitation that it lacks long-term clinical data, it has the advantage being relatively safe and having little side-effects.

Because this study is neither a regional sample study nor a nationwide survey, the results cannot be generalized. However, we believe that this study has significant meaning in that many experts were involved to gather the detailed medical history and prescription status and that this is a relatively large scale study including secondary and tertiary hospitals in Busan. We also believe that an organized and standardized national research is required.

In conclusion, in the type 2 diabetic patients aged 30 years or more enrolled from the general hospitals in Busan, OHA only was the most popular form of diabetes treatment, accounting for two third of patients, followed by both insulin and OHA for one fifth and insulin only for 5%. Over half of all patients were using each of antihypertensive, antidyslipidemic, or antiplatelet agents. A half of all patients were using statins and one third were using aspirin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Tae Yong Kim MD, PhD, in University of Ulsan College of Medicine for his data handling and statistical analysis. This research was supported by Korea Otsuka Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi-Aventis Korea.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Park Y, Lee H, Koh CS, Min H, Yoo K, Kim Y, Shin Y. Prevalence of diabetes and IGT in Yonchon County, South Korea. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:545–548. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SM, Lee JS, Lee J, Na JK, Han JH, Yoon DK, Baik SH, Choi DS, Choi KM. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in Korea: Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2001. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:226–231. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, Peters AL, Tsapas A, Wender R, Matthews DR American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–1379. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Jr, Bigger JT, Buse JB, Cushman WC, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Grimm RH, Jr, Probstfield JL, Simons-Morton DG, Friedewald WT. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko SH, Kim DJ, Oh SJ, Lee HJ, Shim KH, Woo MH, Kim JY, Kim NH, Kim JT, Kim CH, Kim HJ, Jeong IK, Hong EG, Cho JH, Mok JO, Yoon KH, Kim SR Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines Korean Diabetes Association. 2011 Clinical practice guidelines for type 2 diabetes in Korea. J Korean Diabetes. 2011;12:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuang LM, Tsai ST, Huang BY, Tai TY Diabcare-Asia 1998 Study Group. The status of diabetes control in Asia: a cross-sectional survey of 24,317 patients with diabetes mellitus in 1998. Diabet Med. 2002;19:978–985. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol In adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.R Development Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. [cited 2007 Dec 5]. Available from: http://www.R-project.org.

- 9.Park SW, Kim DJ, Min KW, Baik SH, Choi KM, Park IB, Park JH, Son HS, Ahn CW, Oh JY, Lee J, Chung CH, Kim J, Kim H. Current status of diabetes management in Korea using National Health Insurance Database. J Korean Diabetes Assoc. 2007;31:362–367. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim S, Kim DJ, Jeong IK, Son HS, Chung CH, Koh G, Lee DH, Won KC, Park JH, Park TS, Ahn J, Kim J, Park KG, Ko SH, Ahn YB, Lee I. A nationwide survey about the current status of glycemic control and complications in diabetic patients in 2006: the Committee of the Korean Diabetes Association on the Epidemiology of Diabetes Mellitus. Korean Diabetes J. 2009;33:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung BM, Ong KL, Cherny SS, Sham PC, Tso AW, Lam KS. Diabetes prevalence and therapeutic target achievement in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Am J Med. 2009;122:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morimoto T, Fukui T, Lee TH, Matsui K. Application of U.S. guidelines in other countries: aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japan. Am J Med. 2004;117:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, Cobbe S, Taylor R, Prescott R, Lee R, Bancroft J, MacEwan S, Shepherd J, Macfarlane P, Morris A, Jung R, Kelly C, Connacher A, Peden N, Jamieson A, Matthews D, Leese G, McKnight J, O'Brien I, Semple C, Petrie J, Gordon D, Pringle S, MacWalter R Prevention of Progression of Arterial Disease and Diabetes Study Group; Diabetes Registry Group; Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ. 2008;337:a1840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogawa H, Nakayama M, Morimoto T, Uemura S, Kanauchi M, Doi N, Jinnouchi H, Sugiyama S, Saito Y Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis with Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) Trial Investigators. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic events in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2134–2141. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes: 2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(Suppl 1):S11–S63. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park IB, Kim DJ, Kim J, Kim H, Kim H, Min KW, Park SW, Park JH, Baik SH, Son HS, Ahn CW, Oh JY, Lee S, Lee J, Chung CH, Choi I, Choi KM. Current status of aspirin user in Korean diabetic patients using Korean Health Insurance Database. J Korean Diabetes Assoc. 2006;30:363–371. [Google Scholar]