Abstract

Reverse phase protein array (RPPA) technology introduced a miniaturized “antigen-down” or “dot-blot” immunoassay suitable for quantifying the relative, semi-quantitative or quantitative (if a well-accepted reference standard exists) abundance of total protein levels and post-translational modifications across a variety of biological samples including cultured cells, tissues, and body fluids. The recent evolution of RPPA combined with more sophisticated sample handling, optical detection, quality control, and better quality affinity reagents provides exquisite sensitivity and high sample throughput at a reasonable cost per sample. This facilitates large-scale multiplex analysis of multiple post-translational markers across samples from in vitro, preclinical, or clinical samples. The technical power of RPPA is stimulating the application and widespread adoption of RPPA methods within academic, clinical, and industrial research laboratories.

Advances in RPPA technology now offer scientists the opportunity to quantify protein analytes with high precision, sensitivity, throughput, and robustness. As a result, adopters of RPPA technology have recognized critical success factors for useful and maximum exploitation of RPPA technologies, including the following:

preservation and optimization of pre-analytical sample quality,

application of validated high-affinity and specific antibody (or other protein affinity) detection reagents,

dedicated informatics solutions to ensure accurate and robust quantification of protein analytes, and

quality-assured procedures and data analysis workflows compatible with application within regulated clinical environments.

In 2011, 2012, and 2013, the first three Global RPPA workshops were held in the United States, Europe, and Japan, respectively. These workshops provided an opportunity for RPPA laboratories, vendors, and users to share and discuss results, the latest technology platforms, best practices, and future challenges and opportunities. The outcomes of the workshops included a number of key opportunities to advance the RPPA field and provide added benefit to existing and future participants in the RPPA research community. The purpose of this report is to share and disseminate, as a community, current knowledge and future directions of the RPPA technology.

Reverse phase protein array (RPPA)1 technology represents a highly efficient and cost-effective descendent of miniaturized immunoassays that use a sandwich format for antigen capture (1, 2). Immunoassay arrays were generally sandwich-style assays in which a series of antibodies immobilized on the solid phase were used to capture the analyte of interest (“antibody capture”), with a second antibody, directed against a different epitope on the same protein, used as a detection molecule. In contrast, in “reverse phase” the analytes (antigens) are immobilized on the solid phase (usually nitrocellulose) and subsequently probed with an antibody or other affinity reagent toward a specific target. The term “reverse phase protein microarray” was coined by Paweletz et al. in a paper describing the implementation of the technology for application to cell signaling analysis of laser capture microdissected pre-malignant prostate lesions (3). Since then, terms used in the literature have included “lysate array” (4), “reverse phase lysate microarray” (5), “reverse phase protein array” (6), and “protein microarray” (7, 8). For the purposes of this report, and in an attempt to develop a consensus terminology, we use “reverse phase protein array.”

RPPA technology is dependent on the availability of high-quality monospecific affinity reagents, usually antibodies that can detect with high affinity and specificity a protein or post-translationally modified protein on a solid matrix. Further international efforts such as the Human Protein Atlas Project, Antibodypedia, NCI's Antibody Characterization Program, the Human Antibody Initiative, and aptamerbase are underway to develop, catalog, and validate well-characterized libraries of high-quality affinity reagents that can be used by the community. However, it is important to understand that quality control at each step is paramount for the success of RPPA, in particular in the selection, validation, and implementation of affinity reagents. Challenges associated with this are discussed later in the paper. A number of Web-based resources have recently come online that provide details of antibody validation protocols and published lists of validated RPPA antibodies in current use, including the following:

“Antibody Lists and Protocols,” available from The MD Anderson Cancer Center's Functional Proteomics RPPA Core Facility

Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum's page on current protein microarray projects, including RPPA projects

A discussion of protein microarray systems from Zeptosens Bioanalytical Solutions

Furthermore, as the technology is based on a sample-down approach, it is possible to generate and store additional slides (sample arrays) so that further analysis can be performed as new affinity reagents become available or new hypotheses need to be tested. Thus, RPPA provides a highly flexible tool for supporting functional proteomic studies.

RPPA technology has been applied to a diverse range of sample types to achieve a multiplex quantitative measurement of a large number of analytes extracted from a relatively small number of cells. The technology can be used for protein signal pathway mapping in animal models from Drosophila to mouse, in cell lines and xenografts, and in clinical sample profiling. The biological input can consist of enriched cell populations from tissue microdissection (4, 7, 9–15) or from direct extraction of heterogeneous tissue samples (16–21), cell lines (20, 22–25), or subcellular fractions.2 RPPA technology has also been successfully applied to serum/plasma (26–29). The technology is uniquely suited for profiling the state of in vivo signaling networks because of its minimal total cellular volume requirements, high sensitivity (picomole-to-femtomole range), and excellent precision (<15% cv) (3, 6, 13, 30, 31). Reverse phase protein arrays allow quantitative analysis of phosphorylated, glycosylated, acetylated, cleaved, or total cellular proteins from multiple samples as long as specific detection reagents of high quality are available (32). The dot blot approach, which is dependent on the detection of a single epitope by an affinity reagent, usually an antibody, is particularly applicable to clinical samples, as it is less sensitive to protein quality than is a sandwich antibody-like approach in which two independent epitopes and the intervening region must be intact for quantitative analysis. Indeed, with a number of caveats, RPPA can be applied to at least a subset of targets from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded patient samples (33–35).

The RPPA format has been successfully implemented in a variety of formats by a large number of international laboratories. Each laboratory has made significant technical improvements at many stages or has adapted the technology for a particular new use. For example, improvements have been reported concerning the substratum and data capture. Functionalized glass (36, 37), hydrogel (38, 39), PVDF (40, 41), macroporous silicon (42), nitrocellulose polymers (43, 44) (Grace Bio-Labs; Maine Manufacturing; Sartorius), and planar wave guide surfaces (ZEPTOSENS) (45) have all been successfully implemented to improve sensitivity, spot morphology, precision, and accuracy. Further marked improvements have been made in informatics approaches to deal with sample handling, regional staining correction, quality control, and the identification of high-quality samples and reagents. In many cases these have been integrated into publicly available algorithms such as “Supercurve” (46), “Normacurve” (31), and the RPPanalyzer that is available as an R-Package on the CRAN platform (47).

The technology has entered the biotechnology sector under two models: (i) a fee-for-service model, and (ii) as a research tool used in basic and clinical research. Recently, RPPA technology graduated to use in national clinical trials (48) in a focused personalized medicine trial, and it has become an integral part of large-scale cell line and patient sample characterization efforts such as the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia, the Cancer Genome Atlas, and the ISPY2 adaptive design clinical trial.

The first three Global RPPA Workshops, held in Houston, TX (Oct. 10–11, 2011), Edinburgh, UK (Nov. 12–13, 2012), and Kobe, Japan (Nov. 12–13, 2013), highlighted that, at that point in time, it seemed particularly appropriate to gather together the collective wisdom of the RPPA user community for several important goals. The first goal was to share and disseminate the latest technologies, algorithms, databases, and best practices from each of the participating labs. The second goal was to share lists of validated antibodies and other affinity reagents applicable to RPPA to create a common database for all RPPA users. As the validation of high-quality affinity reagents remains the rate-limiting factor for the implementation of RPPA, a community effort would increase utility, decrease redundancy, and decrease costs. A third goal was the development of general recommendations for sample collection and handling, arraying, data collection, and bioinformatics. The institution of standardized protocols was not the goal of the working group, as the technology is still evolving and a need for flexibility and innovation remains paramount. Nevertheless, the establishment of guiding principles and sharing of best practices and algorithms for quality control for RPPA technology can be essential for (a) accelerating the learning curve for new users, (b) increasing the utility of the platform, (c) clinical trial design and approval, and (d) use of the technology under College of Academic Pathologists/CLIA compliance. The creation of an RPPA society and the organization of yearly workshops were considered essential in order for these goals to be attained. Here, we aim to share and disseminate, as a community, current knowledge and future directions of the RPPA technology. These will now be discussed in further detail.

RPPA: The Process

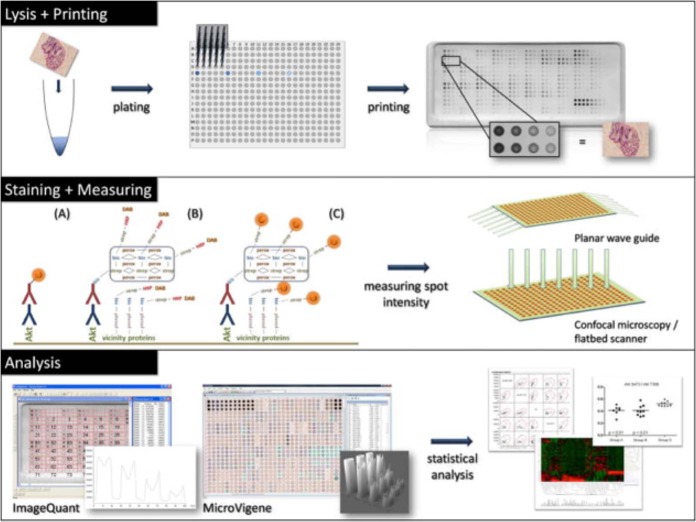

The general process of RPPA is outlined in Fig. 1, and the following subsections discuss key areas that were identified in the workshops as requiring specific consideration with regard to current challenges, optimal performance, and future development. For further detail on more general methods and protocols relating to RPPA, we refer readers to specific publications dedicated to this topic (49).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the RPPA workflow. Reprinted from Mueller, C. M., Liotta, L. A., and Espina, V. (2010) Reverse phase protein microarrays advance to use in clinical trials. Mol. Oncol. 4, 461–481. Copyright (2010), with permission from Elsevier.

Protein Extraction Methods

Protein extraction from cells and tissues is a critical step in any proteomic analysis, and it is imperative that protein samples be prepared in appropriate buffers using standardized operating procedures that maintain the integrity and activity of protein analytes under evaluation. Protein extraction is typically performed in a buffer containing chaotropes such as urea or detergents (e.g. Nonidet P-40, Triton X-100, CHAPS); reducing agents; and inhibitors of proteases, phosphatases, and oxidoreductases (50). However, many buffer types are suboptimal for the solubilization of specific protein classes such as membrane or other highly hydrophobic proteins. The development of specialized buffers including urea/thiourea mixtures and new zwitterionic detergents such as sulfobetaines have improved the solubilization of hydrophobic proteins (51–53).

A further consideration for certain RPPA studies may be extraction of the relevant protein fraction. Lipid rafts within the plasma membrane are important molecular platforms for signaling function, and specialized methods have been developed to enable the extraction of detergent-insoluble lipid rafts for proteomic analysis (51). Sonication methods or stronger detergents may be required for efficient extraction of analytes integrated within compacted cytoskeletal or heterochromatin structures. Increased sensitivity of low-abundant nuclear and DNA binding proteins may be further enhanced by isolating nuclear fractions prior to protein extraction and RPPA (54). Further evolution of subcellular fractionation protocols for proteomic studies compatible with the handling of multiple samples suitable for RPPA might enhance the sensitivity and analysis of specific subcellular compartments and spatially distinct signaling complexes. It is clear that a single protein extraction buffer or method will not be suitable for every RPPA platform, printing substrate, and analyte. Further comparison of the performance and representation of the proteome using different protein extraction buffers will enable a greater understanding of the limitations and benefits of different buffers and methods of protein extraction for RPPA.

Array Printing: Considerations and Current Challenges

A wide range of slide formats are commercially available (1–64 pads/subarrays per slide) for the immobilization of protein samples enabling the development of focused, high-throughput, multiplex assay formats. The first step in generating an RPPA is the selection of a suitable substrate for printing, the most common of which is nitrocellulose. There are also a number of important considerations when choosing lysis buffers and spotting buffers to ensure compatibility with both the substrate and the arrayer. The inclusion of harsh or excessive amounts of detergents can induce “foam formation” effects, hampering sample recovery and microarray printing. Extraction buffers and methods that create samples with high viscosity might not be suitable for certain printing platforms. High detergent concentrations in samples can also impair the immobilization of protein samples on specific hydrophobic substrates utilized in RPPA, adversely influencing microarray quality.

Currently, a number of different printing technologies are used for sample deposition, namely, solid pin contact, piezoelectric, and inkjet spotting. Like many technologies, each of these has advantages and disadvantages; therefore, it would not be appropriate to recommend one particular type of arrayer for the generation of RPPA. The temperature and humidity during the print run also require careful consideration to minimize sample evaporation and maximize sample preservation. Environmental control is a feature built into many commercial arrayers. Thus, there are a number of important parameters that require optimization for the successful generation of high-quality RPPAs.

The standard approach, used by many in the field, is to print each lysate as a serial dilution, with subsequent detection using high-affinity reagents, as initially implemented by Liotta, Petricoin, and colleagues (3) Generally, it is accepted that this concept provides an improved quantitative readout and better quality control relative to sample analysis in a single concentration format as realized in the initial dot blot approaches. However, preparing, managing, and printing serial dilutions from large numbers of samples (e.g. several hundreds) is very demanding in terms of time, and printing large numbers of samples can quickly exhaust the capacity provided by the 2 cm × 7 cm area of the standard single-pad slide format (Fig. 1), as well as introduce variance due to manual serial pipetting. As an alternative to printing each sample as a serial dilution, it is possible to print serial dilutions of reference lysates that contain differing amounts of the target analyte as a calibration curve that spans the linear dynamic range of the assay, as well as high and low controls, and to include individual experimental samples in a single concentration, adopting a format more closely related to that used in a standard ELISA or clinical immunoassay. This strategy can be especially advantageous when the starting concentration of the analyte of interest is extremely low and dilution series spots would not contribute to the quality of quantitation (e.g. laser microdissected clinical tissue).

In summary, current RPPA approaches meet the technical requirements for cost-effective and quantitative analysis of cellular proteomes in a flexible format. Samples can be analyzed in small numbers (e.g. 5 to 50 individual samples), but the analysis format can easily be expanded to compare thousands of individual samples in parallel. This scale of throughput is currently not feasible with conventional Western blot or any other proteomic technology. In addition, the flexibility of the platform for the analysis of large sample numbers in parallel either for the protein network of choice or in an unbiased manner remains a major strength of the platform.

Validation of Affinity Reagents for Use in RPPA

Antibodies are among the most commonly used tools in basic science research, as well as within clinical assays. In RPPA they are used to detect the protein of interest in cell, tissue, or blood lysates. Like other widely used clinical immunoassays such as immunohistochemistry (IHC) that are dependent on the fidelity and specificity of the primary and secondary antibody binding, the reliability of RPPA results largely depends on the quality of the antibodies used. However, universally accepted guidelines or standardized methods for determining the validity of antibodies for use in RPPA have not yet been established. In a typical RPPA assay, as in IHC, there is no separation of the proteins according to molecular weight; therefore, antibody validation is crucial for the outcome of the assay, as signals from potential cross-reactivities cannot be distinguished from specific signals. Although the RPPA technology is currently based primarily on the use of antibodies as affinity reagents, other reagents such as aptamers could be applied. However, it is expected that the underlying principles of quality control and validation will remain a key challenge.

A “validated” antibody must be shown to be specific, selective, and reproducible in the context for which it is to be used. For RPPA, a good correlation between explainable bands in Western blot and RPPA data should be demonstrated. Further, the antibody must perform robustly across different sample types and over time. It is critical to emphasize that the quality of many antibodies, both monoclonal and polyclonal, can change over time, requiring revalidation of different batches. Furthermore, ongoing studies can reveal previously unnoticed liabilities, requiring reevaluation of the validation status of many antibodies. Given the known and unexpected liabilities of affinity reagents, it is optimal to confirm the results of an RPPA study with an orthologous technology where possible. Indeed, the RPPA platform is ideally suited as a discovery or primary screening platform. Nevertheless, with the appropriate quality control and high-quality reagents, the RPPA platform can provide the precision and robustness exemplified by other approaches such as ELISA or IHC tests.

Three general approaches for antibody validation have been described. 1—Perform RPPA on a large panel (>10) of cell lines and/or tissue samples, then do Western blotting on those samples that show differential expression. This is a cost-effective approach and ensures that Western blotting is done on samples with a wide dynamic range, a prerequisite for validation. 2—Perform antibody validation on a panel of standard cell lines with Western blot. Confirmation of results obtained from the Western blot with RPPA needs to be shown afterward (“reverse validation”). 3—Western-blot-based antibody validation using the material later intended for the use of the RPPA (e.g. human tissue lysates). In this case, potential cross-reactivity of the antibody should be detected before the antibody is used for RPPA. In either case, the two minimum criteria for antibody specificity are explainable single or multiple bands in a Western blot and good correlation between Western blot and RPPA results. Indeed, the correlation between Western blot and RPPA data provides a good indication of antibody quality. However, the number and spectrum of samples on which the correlation is established will affect its power. On a typical Western blot, 10 to 15 samples are tested. If the same samples are present on the RPPA array, a standard Pearson correlation can be made. However, if the expression level among all samples is similar (a histone protein, for example), or if, in contrast, expression is seen in only one sample (a protein involved in apoptosis, for example), the correlation is not representative and is subject to potential artifacts. In addition, it can matter whether the correlation is based on raw data or on normalized data, and in the latter case how the normalization was done. Thus, correlation coefficients from different laboratories are not directly comparable. Nevertheless, they remain of importance as an objective indication of antibody performance and can be used to categorize antibodies with regard to their specificity as follows: (i) highly specific, (ii) use antibody with caution, or (iii) antibody is not reliable.

Additional validation methods for affinity reagents may include perturbed systems—the use of an agonist or antagonist to, respectively, activate or inhibit a specific signaling pathway before Western blot and RPPA analysis; the use of a phosphatase when a phospho-epitope is to be validated; overexpression or inhibition by siRNA of the gene of interest; or the use of cells or tissues from transgenes or knockout animals. In the case of tissue samples, a combination of two different methods may be used to validate an antibody (e.g. IHC and Western blot) (55). Higher throughput Western blot analysis including the so-called microwestern array technology (56) or automated capillary-based systems including Simple Western™ technology from proteinsimpleTM will help overcome analytical and throughput bottlenecks in conventional Western blot analysis, expediting antibody validation for RPPA. The application of further technology advances (e.g. hybridoma and phage-display technologies) in a coordinated large-scale antibody generation and validation effort might help in the future with the generation of specific and renewable “protein binders” (57, 58).

Many other ancillary approaches can contribute to confidence in the robustness of RPPA data and thus the antibodies used. For example, a high correlation between protein levels in an RPPA analysis with RNA levels in the same sample set would argue for antibody validity. However, as post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation are common, protein levels, and in particular post-translational modifications, often do not correlate with RNA levels, and therefore a lack of correlation between RPPA and RNA levels does not invalidate an antibody. Further, coordinate expression patterns of individual proteins, in particular proteins and post-translationally modified proteins within a specific signaling pathway, adds to the likelihood that the antibodies used are valid.

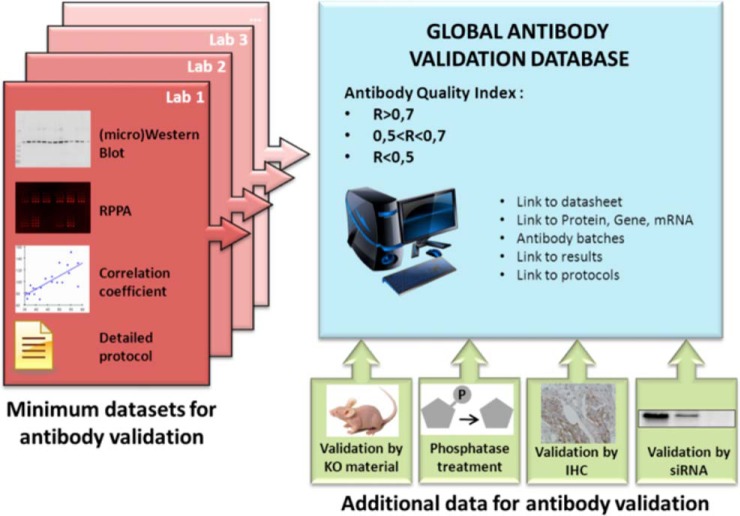

Antibody validation is both time consuming and costly. Sharing antibody validation data, therefore, seems an obvious way to accelerate research. Beyond the RPPA community, these data are of interest for many laboratories and many applications. Although validated antibodies can only be considered as such in the samples (and under the conditions) that they have been tested in, an antibody that performs well in a particular context is more likely to give satisfactory results in other assays (59). It is also likely that the RPPA format and experimental conditions utilized could alter the validity of particular antibody reagents. Indeed, reagents that perform well on cell line studies might not perform well in patient samples, and antibodies that provide accurate results with human tissues might not be usable with other species such as mouse (because of binding characteristics and cross-reactivity with murine immunoglobulin) and drosophila. Thus, a global antibody database would be cost effective and could provide important information to guide laboratories in the selection of antibodies to test in their own platforms and assay conditions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A global database providing a quality index for antibodies and comprehensive information about the validation process will be the first stop for researchers performing the RPPA technology.

Few studies have been published on antibody validation for RPPA. An important effort has been made by Major and colleagues (60) through the creation of AbMiner, a valuable database of more than 600 antibodies. This database includes Western blot results, from tests performed on a pool (mixture) of 60 cell lines, and refers to official naming of the genes and proteins targeted by each antibody. However, to our knowledge, the database is not up to date (antibody validation was performed in 2001–2003), does not provide links to the validation data, and does not include comparison between RPPA and Western blot. The ASKMD database of 279 antibodies described by Spurrier and colleagues (61) is no longer accessible. More recently, Mannsperger and colleagues (62, 63) tested antibodies via Western blot followed by RPPA on samples in which the target protein had been depleted by siRNA. In this manner, they described the validation of antibodies for up to 26 proteins. Although very powerful, this approach seems incompatible with the high-throughput validation of large panels of antibodies. Sevecka and colleagues (59) have attempted to increase the throughput of antibody validation for RPPA. They tested 383 commercial antibodies, first with RPPA and then via Western blot. For RPPA, they selected only those antibodies that showed a significant difference in expression among a panel of 11 cell lines grown in different conditions. Indeed, they reason that an important amount of nonspecific binding would cover specific signals and thus flatten out the differences among samples. This approach assumes that nonspecific binding is of similar intensity among all samples, which is not always the case. Nevertheless, performing RPPA prior to Western blot allows for (i) primary selection of the antibodies and (ii) further testing of the successful antibodies via conventional methods on those samples that show differential expression according to RPPA. The authors validated only those antibodies that showed a good Pearson correlation (r > 0.75) between normalized RPPA data and Western blot intensities. Using these criteria, 82 out of 383 antibodies were validated. Other groups have published lists and validation status for specific studies; however, the validation approaches and, in particular, primary data are often not available for inspection and quality control.

These examples of published antibody validation sets show the different requirements (and pitfalls) of a global antibody database. In order to serve the RPPA community, such a database would be required to meet the following criteria:

Continuously updated by multiple laboratories

Includes details of methods used for validation

Includes the validation data (Western blot and RPPA images)

Indicates the correlation coefficient between Western blot and RPPA for each antibody

Making such a database publically available is also expected to impact positively on antibody suppliers, as it would be in their best interest to have an important fraction of validated RPPA antibodies from their respective portfolios in this global database.

Detection and Processing

Possibly the largest divergence among RPPA laboratories concerns technical approaches employed for the visualization and analysis of antibody signals. Approaches include visualization via dye precipitation, chemiluminescence, near-infrared dyes, quantum dots, and ultrasensitive planar waveguide technologies. Different detection approaches require specialized instrumentation to generate high-resolution digital images that can subsequently be used for data analysis. Importantly, the choice of detection strategy can greatly influence the performance of the assay by reducing background and increasing the dynamic range and sensitivity. In some cases RPPA detection hardware and analysis software are platform specific, as is the case for ZeptoREADER and ZeptoVIEW software integrated within the Zeptosens platform provided by Zeptosens-Bayer Technology Services. Other hardware and software solutions are platform agnostic, such as standard/infrared microarray readers; conventional and infrared flatbed scanners; and microarray image analysis software like MicroVigeneTM (VigeneTech), GenePix Pro (Molecular Devices), Array-Pro Analyzer (Media Cybernetics), and Mapix (Innopsys), each of which can be tailored toward RPPA. Each approach has its own particular strengths and limitations that must be considered in data analysis and in the interpretation of the resultant data. For this reason, it is not appropriate to recommend a particular approach at this point in time. However, it is critical that all developers and users rapidly share best practices and approaches to ensure the implementation of robust approaches in a cost-effective manner.

A key feature of RPPA is that the detection reagents (e.g. antibodies) are physically separated from each other. Thus, each array or subarray is probed with a single antibody and represents an independent entity. To enable mass-parallel multiplex analysis, biological samples are immobilized on multiple replicate arrays. For this reason, in terms of quality control within a specific study, it is important to assess the coefficient of variation within results from a single affinity matrix. However, assessment across slides and experiments provides important quality control information on the printing, affinity reagent, development, and imaging approaches. This information is of particular importance when attempting to combine information across studies. There are multiple approaches for assessing the quality of an individual RPPA slide that can exploit the unique properties of RPPA including printing of standard samples, high and low controls, calibrator curves that span the dynamic range of the assay, and analysis of the behavior of all samples. Information obtained from these samples serves as a basis for judging data quality and monitoring reproducibility. The discussion on how to judge the quality of individual arrays revealed that most investigators would want to know what range of cv is commonly considered as acceptable for data analysis.

Analysis Software

General Considerations

The first step in the analysis of RPPA data is the quantification of the raw signal intensity of each spot. For this, powerful and flexible software tools are required that robustly localize spots on the arrays while being capable of adapting to every potential layout of the slide. RPPA arrays generally contain dilution series of at least a fraction of the samples, and the software thus needs to correctly detect spots with intensities varying from background to saturation levels within one array. Furthermore, current printing devices allow many types of customized layouts, containing several levels of subgridding combined with randomized sample deposition. Ideally, the printing device communicates with the quantification software to inform about the design and the localization of each lysate. Importation of the sample name and its dilution step, corresponding to each spot, is an absolute requirement for further data analysis and can be done either at the level of the printer or before array quantification.

In addition, the quantification software can propose a first local background correction, and the possibility of implementing additional analysis packages, for quality control and data processing, can be of interest.

Current Packages in Use

A number of commercial software packages are currently in use for the analysis of RPPA data. These include MicroVigene (VigeneTech), Array Pro (Media Cybernetics), GenePix Pro (Molecular Devices), and Mapix (Innopsys). With the exception of MicroVigene, these packages are designed for standard microarray analysis, but they are sufficient to perform many of the basic functions required in the initial stages of RPPA analysis.

Future Requirements

Instead of having separate software tools for printing, labeling, quantification, and analysis, RPPA would benefit from a single software tool that allows automated sample management throughout all steps, from sample lysis up to quality control and statistical analysis, including quantification of the data. Barcoding each sample and each array facilitates this process. The name and the dilution step of each lysate, and its precise localization on the array, could be automatically traced, thus minimizing errors due to manual intervention. However, none of the RPPA platforms currently have the exact same operating procedures and the same equipment; therefore, the exact requirements would be different for each laboratory. Important in-house efforts have been made to develop such tools,3,4 which could be adapted by other laboratories to their local workflow. As RPPA becomes more widely used in a clinical laboratory environment, incorporation of these software management tools will graduate under formal laboratory information management systems–based oversight, as a regulatory requirement.

Additional Software Currently Available for Improving the Quality of RPPA Data

Once spot intensities have been quantified using software (such as that detailed above), it may be necessary to perform additional data processing steps before the data can be used for analysis. It is important to note that these steps will vary depending on the method of detection used (e.g. background is generally greater when using colorimetric versus infrared detection). This section discusses the steps needed to remove nonbiological artifacts from the data, from single slides to multiple batches of slides.

Correcting Spatial Effects When Processing a Single Slide

Spot intensities and non-printed background intensities may vary on a slide depending on their location. Those spatial effects may be due to a variety of factors, including nonspecific binding of the secondary antibody or components from the signal amplification steps to contaminants or the slide substrate itself. As a result, a slide may show patches of high or low intensity across its surface; therefore surface adjustment is required to account for that technical variation. Positive and negative controls spotted on the slide can help to address such spatial defects and thus greatly improve inter- and intraslide spatial variabilities (64–66). Positive controls can be mixtures of cell lines that express all the proteins of interest or standard analytes representing the antibody target, whereas negative controls are buffers, preferably containing amounts of protein similar to that in the test sample, that do not bind to any antibody. As the positive controls should all be expressed at the same level, any differences between spots on the array can be attributed to spatial effects. The underlying principle is to compute the level of background noise at each location on the slide and remove it from the observed intensities.

Obtaining a Single Value from a Dilution Series When Processing a Single Slide

Samples are often spotted on arrays in a dilution series, often consisting of 5 to 10 spots. Using a mathematical model, the dilution series is converted into a single value that is indicative of the protein concentration in the sample. Various models have been proposed in the literature, making different assumptions about the data. They range from linear models (3) to log-linear (67), logistic (22), and non-parametric (46). Of these, the non-parametric model makes the least restrictive assumption that the observed intensities increase monotonically with respect to the true protein concentrations. However, at very low or very high intensities, the models tend to saturate at either extreme, and the results become less reliable. Indeed, the key limitation is that several of the dilutions need to be in the “linear” range of the concentration curve. Further, contributions of background at high and low dilutions will be different, potentially displacing the curve.

Processing Several Slides of the Same Antibody

Surprisingly, processing identical sets of samples on different slides labeled with the same antibody can result in datasets that have very different means and variances. Neeley et al. (68) processed clinically similar acute lymphoblastic leukemia samples in two batches and observed differences in their protein data distributions. There were additive and multiplicative effects in the data that could not be accounted for by biological or sample loading differences. They developed an algorithm called variable slope normalization to detect and correct the multiplicative effects. The additive effects can be removed by median-centering all the samples on a slide. Applying those methods allows effective comparison of different slides labeled with the same antibody, provided the sample sets on the slides are biologically similar to each other. Indeed, this approach tends to normalize differences between samples and in particular is dependent on the sample sets' sharing a similar “structure” in terms of types of samples and levels of proteins.

Processing a Sample Set Across Several Different Antibodies

Sample loading differences can occur as a result of several factors, such as differences in protein concentration, heterogeneity in cell size, or heterogeneity in the cellular compositions of tissues. In addition, protein degradation or access of antibody to protein in spots can vary. Several methods for normalization can be used. Normalization toward (a set of) housekeeping proteins should be used with caution, as the stability of these proteins in the studied lysates is difficult to assess. Currently, methods for staining total protein are widely used, such as Sypro Ruby, FAST green, and colloidal gold (31). Samples can also be normalized to DNA content, particularly when the sample is contaminated with blood, fat, or high-abundance proteins (69). When a large series of proteins has been studied, the observed expression levels of many different proteins in one sample allow estimation of the differences in the total amount of protein in that sample versus other samples. Indeed, when a sample shows low expression levels for dozens of phosphoproteins that act in different pathways, this may be considered as a potential bias due to low protein quantity/quality in that sample and should be flagged for further analysis. To correct for such sample loading differences, the median protein expression in a sample can be normalized using all of the expression levels for that sample. That makes the median protein expression for all samples equal to zero, accounting for any loading differences. The procedure enforces the assumption that the relative amounts of proteins in each sample are the same and that one sample does not truly over- or underexpress all studied proteins (regardless of whether that is biologically true or not).

If the sample is a biological fluid, such as plasma, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, saliva, or some other, less conventional type of liquid sample, normalization will have to be to volume. Intuitively, most clinical tests of biological fluids are based on the concentration of an analyte, not the total mass. Therefore, simply printing a sample, without concern for the included quantity of protein, is the recommended strategy (70, 71). Secondly, if a fluorescent small molecule is included in the sample, a representation of the volume printed can be accurately determined on a fluorescent slide reader. In the interest of conserving slides, the fluorescent small molecule can be washed away as part of the routine workflow, or the slide can be developed using a method that is insensitive to the fluorescent signal, such as dye deposition.

We must remember that unless well-established calibrators with known protein concentrations are printed along with the samples, RPPA provides relative data, not absolute. We can therefore only compare concentrations relative to other samples using the same antibody. Because the coefficient of proportionality of observed values versus true concentrations may vary from one antibody to the next, we cannot directly compare observed data values to make inferences about concentrations of different proteins. For instance, in the absence of calibrators, we cannot directly infer that the concentration of protein x is greater than that of protein y in sample j, or vice versa. Further, inherent characteristics of each antibody such as affinity and background can influence the apparent concentration of the analyte. These challenges must be borne in mind when performing analysis across different proteins.

Many of the techniques described above are implemented in the SuperCurve (46) and NormaCurve (31) software.

Processing Multiple Batches of Samples Across Several Different Antibodies

When processing multiple batches of samples, we have to consider potential batch effects. Batch effects are technical variations that are inadvertently introduced during sample extraction, shipping, or processing. Common methods used to assess batch effects include clustering, singular value decomposition/principle component analysis, or standard statistical tests such as t test or F-test. When using clustering or singular value decomposition/principle component analysis plots, we determine whether samples cluster together by batch or whether they are evenly dispersed in the plots. If the batches are clinically similar to each other but the samples cluster together by batch, this might indicate potential batch effects. Many different algorithms are available to correct for batch effects, including empirical Bayes (72) and analysis of variance. However, in trying to correct for technical variation, we might end up diminishing biological variation as well, so such approaches must be used with caution.

In summary, there are a number of different software packages available for further processing of RPPA data. Although these assist one in “cleaning up” the data, it is important to use these with caution so as to not overprocess the data and risk losing true biological relevance and insight. The software packages outlined above can be applied to many types of RPPA data; however, they are insufficient for use in real-time clinical assays. Alternative approaches for processing clinical data are discussed below.

Current RPPA Applications

Basic Research

Although many of the underlying causes of human disease occur at genetic and epigenetic levels, disease pathophysiology and drug response are dictated by cellular phenotypes that in turn are regulated at the post-translational protein level. The cellular proteome is an interconnected network of signaling pathways that control specific cellular functions. These signaling networks are dynamic and continuously adapt to environmental cues and biochemical or pharmacological perturbations affecting cell function. No single protein acts in isolation; thus detailed mechanistic analysis of gene, protein, and cell function requires the study of integrated signaling networks for a particular biological context. Functional proteomics describes the large-scale study of protein expression levels, post-translational modifications, and activation states supporting the systematic analysis of signaling networks that control biological function. Traditionally, proteomic methodology relied on quantitative mass spectrometry techniques that remain the standard for the de novo identification of post-translational modifications that might represent markers for specific biochemical signaling pathways or biological events. However, limitations regarding the speed, cost, and sensitivity of mass spectrometry restrict high-throughput application across multiple samples. The evolution of the RPPA method combined with more sophisticated sample handling and optical detection provides new advances in the sensitivity, throughput, and speed of functional proteomics. Thus RPPA has emerged as an alternative and complementary approach to Western blot, ELISA, and mass spectrometry methods by providing quantitative and high-resolution analysis of the dynamic state of post-translational signaling networks that supports a broad range of basic science applications.

Basic research applications of RPPA include the following:

Understanding pathway regulators implicated in cell differentiation and embryonic development

Elucidating signaling pathway cross-talk following siRNA/shRNA/small molecule targeting

Functional genomics: pathway analysis of genome-wide screens or selected transgenic knockout studies to link gene function to key pathway nodes

Characterizing the host pathway response following bacterial or viral infection

Providing empirical input into the development, iteration, and validation of mathematical modeling and other systems biology tools

Indeed, protein levels and activation status are not static but dynamic, and these dynamics can be addressed by perturbed systems as well as by time course studies (73). A recent study demonstrated the power of dynamic profiling of post-translational signaling events by RPPA by demonstrating that time-staggered inhibition of EGF sensitizes cancer cells to genotoxic drugs (74). Such temporal analysis of pathway signaling at post-translational levels provides additional context to the field of functional proteomics by informing on the precise sequence and duration of post-translational signaling events necessary to produce a specific functional outcome. Such datasets are ideally suited to building more accurate mathematical models that can be used to predict how dynamic remodeling of pathway networks can modify cell function (74). However, the number of samples easily exceeds 1000 in these types of analyses (59, 75). RPPA is currently the only technology capable of analyzing protein pathways in such large series of samples simultaneously, and the RPPA technology provides a tremendous contribution to our systems biology modeling of cancer based on network models (76–80) and can serve to validate the integrity of established mathematical models (81). It is still a challenging field, but the unique ability of RPPA to accommodate large numbers of lysates in a cost- and time-efficient manner clearly provides an opportunity for discovery and validation in the field of systems biology.

Drug Discovery/Biomarker Research

Drug targets are typically proteins; thus, although the therapeutic response is often influenced by underlying genetic factors, a drug's mechanism of action and drug sensitivity are ultimately dictated at the protein level. Many diseases are now considered a consequence of malfunctioning pathways, and for those complex disease traits that do not represent single gene disorders, the pathway networks that control and predict therapeutic response are unclear and may be distinct across a heterogeneous patient population, distinct anatomical sites, and evolving disease etiology. Heterogeneity in a disease mechanism at the pathway level represents a contributing factor to poor clinical efficacy and high attrition rates during drug development. Therefore, only by studying the proteome can we obtain a clear understanding of a drug's mechanism and the relationship between pathways and potential targets that can inform new drug discovery and biomarker discovery programs that embrace the complexities of disease. RPPA technology is particularly well suited to drug and biomarker discovery as a result of the high-sensitivity, high-reproducibility, high-throughput, and quantitative features of the approach. Recent studies have applied RPPA to determine the mechanism of action and selectivity of emerging drug candidates at the pathway level (82), as well as to uncover unexpected drug resistance mechanisms (83). Dose- and time-dependent profiling of pathway responses via RPPA following exposure of cultured cells to candidate drugs enables precise calculation of the potency upon key signaling molecules. Correlation of potency (e.g. EC50) values across multiple analytes at sequential time points following drug addition enables discrimination of off-target activities from downstream signaling and pathway cross-talk events (82, 84).

Combining RPPA with quantitative microscopy extends the field of high-content biology from purely microscopic measurement of cell morphology and specific subcellular molecules to precise measurements of multiple signaling pathways following compound dosing. A combined approach employing high-content imaging and RPPA profiling facilitates a more unbiased approach to classifying drug mechanisms of action and triaging optimal compound mechanisms of action for further development (85). Such applications are well positioned to support the reemerging area of phenotypic drug discovery, in which candidate drugs are selected on the basis of their biological properties rather than potency upon a single target (86, 87).

An important area of modern drug discovery is the identification of predictive biomarkers that enable future patient stratification strategies and/or inform on appropriate combination and alternate therapies to counteract anticipated drug resistance mechanisms. Separate studies by Cardnell and Byers and by Ummanni et al. correlated drug sensitivity across a panel of small cell lung cancer cells with basal levels of protein and post-translational modifications determined via RPPA to identify minimal sets of protein markers that predict drug sensitivity and resistance (88, 89). Thus, RPPA can be used to identify therapeutic response markers that might be readily suitable for the development of antibody-diagnostic tests to select patients for treatment study. The identification of pathway markers of drug resistance can be directly cross-referenced to approved drug or broader drug-target databases to build rational drug combination hypotheses for further testing (90). RPPA has been used to identify new, unexpected mechanisms of targeted therapy resistance. In such work the ability to quantitatively measure the activation state of many dozens of signaling proteins at once was exploited (83), and the results pointed to the need to alter the way certain kinase inhibitors are selected and graduate within the lead optimization process. The application of these approaches at the preclinical phase might help reduce high attrition rates in drug discovery and development by supporting investment in movement of the most promising candidate drug biomarker and/or candidate drug combination strategies forward into clinical development.

Key drug discovery and biomarker applications include the following:

Target validation at the post-translational pathway level

Compound screening: accurate EC50 value determinations across dose- and time-series studies to define on- and off-target effects

De-orphanize compounds with unknown modes of action through pathway screening

Drug candidate profiling: establish pathway activity profiles across a range of preclinical models to inform disease positioning

Drug repurposing: disease repurposing of candidate drugs based on pathway-level activities

Predictive pharmacodynamics: monitoring organ-specific pathway effects in vivo

Rational drug combinations: identification of compensatory and redundant pathway mechanisms to inform drug combination strategies

Biomarker discovery: detection of preclinical pharmacodynamic biomarkers to guide in vivo and clinical drug dosing and scheduling; identification of putative predictive biomarkers in preclinical discovery to inform future pharmacodiagnostic strategies

Clinical Applications

RPPA has attributes that favor immediate adoption for translational research and biomarker guided clinical research trials. RPPA's clinical utility is based upon a number of key and unique attributes of the technology. Firstly, RPPA provides tremendous analytical sensitivity, for both tissue markers and body fluid analytes (3, 71, 91–93). Depending on the affinity and avidity of a given antibody, a few thousand molecules of a given analyte can be accurately quantitated in a given sample. No existing competing technology can quantitatively measure large numbers of low-abundance analytes, such as phosphorylated signaling proteins, from a single small sample input (71, 94). Often the amount of a given tissue or body fluid sample from a clinical trial/patient sample is very small—for example, a few microliters of nipple fluid aspirate. Tissue samples in a given clinical trial biobank from neoadjuvant and metastatic sampling are usually small-bore core biopsies or fine needle aspirates with exceedingly small amounts of target material available for analysis. In these instances, RPPA has been shown to be able to concurrently measure a large number of analytes (95) with analytical precision and accuracy as good as or better than clinical-grade assays such as ELISA (27). Secondly, RPPA provides the opportunity to study hundreds of patient samples simultaneously through the massively parallel printing of small amounts of cell lysates or biofluids on a single affinity matrix. This reversed orientation format then generates extremely reproducible results with cv values that are often less than 5% (71, 91). The resulting format of serial slides supports discovery science, in that almost any question regarding proteins or post-translational modifications of proteins can be simultaneously asked of hundreds of patient samples, provided that appropriate high-quality affinity reagents are available. This platform also supports hypothesis-driven science, in that once a “hit” has been detected, massively parallel, hypothesis-based proteomic interrogation of a large ensemble of samples becomes possible. The outcome can be the detection of a unique change in the expression of one or a few proteins, or a pattern of changes in many proteins, or the identification of a dysfunctional signaling pathway or network. The ability to analyze thousands of samples is particularly important for studies of human tissues and for a thorough statistical analysis such as required by Bayesian modeling and genome-wide screening approaches.

However, there are many strategic decisions to be made and problems to be solved before success can be ensured with this novel proteomics approach in clinical medicine, because of the complex nature of clinical samples. We mention a few of them here, along with some of the solutions that are currently available in the RPPA armamentarium.

Data Normalization for Clinical Applications

Assuming that initial quality control experiments have been satisfied in terms of antibody performance, the first concern is how to normalize the data obtained from the microarray. This is described in detail in a preceding section.

Quantitation of the Data

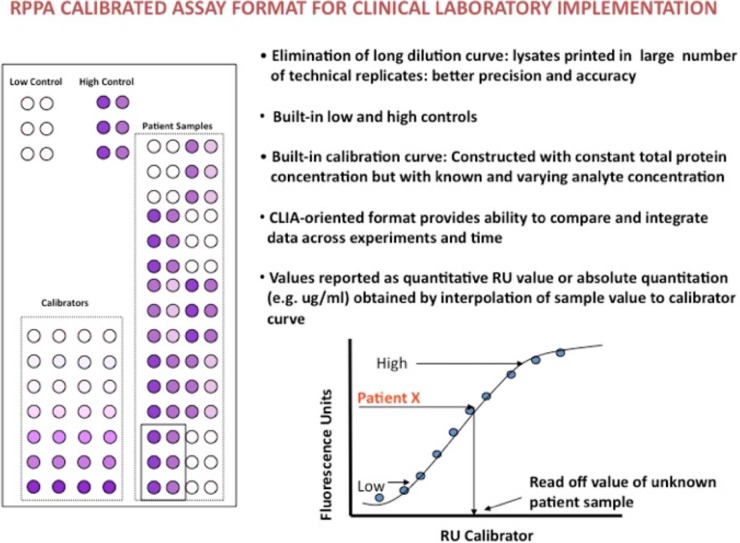

In the early clinical applications of the RPPA technology, most investigators were satisfied to characterize their set of clinical samples based on relative protein levels across the samples analyzed. However, currently the best way to approach quantitation is to print standard curves of purified proteins corresponding to the specificity of the antibodies to be tested on the array. The originating RPPA papers used dilution curve approaches to determine the linear dynamic range of antibody signals (3). More recently, others have proposed further methods such as SuperCurve (46) or NormaCurve (31) approaches for data normalization and analysis. Although these approaches are highly useful for the comparative analysis of many samples, these types of approaches are not sufficient for real-time clinical implementation in which the determination of a given patient value above or below a predetermined cutoff point is required. In these instances quantitation of the analyte is needed where the RPPA assay becomes a calibrated immunoassay equivalent to an ELISA-type approach that has demonstrated clinical utility (96, 97) (Fig. 3). In such instances, a calibrator comprising known amounts of the target analyte (or analytes) varies by prespecified amounts while the background matrix (which should be similar or identical in nature to the clinical samples analyzed) remains invariant. A calibration curve is not the same as a simple dilution curve where the total protein and the analyte are co-varying at the same time. In such instances (dilution curve approaches), nonspecific binding of the secondary and primary antibodies changes in variable ways depending on the concentration of the input sample and the analyte within the sample itself. With a calibration curve, nonspecific binding is more consistent, as the total protein amount remains constant, but the target analyte varies by predetermined amounts. The result is that quantitative values for patient samples can be specified in terms of specific amounts such as pg/mg protein for solid samples or pg/ml for fluid samples by interpolation to the calibration curve. Moreover, in accordance with FDA-cleared immunoassay methods such as ELISA and dot-blot assays, clinical implementation of RPPA should include low and high controls that are above and below any cutoff point used for decision making. Importantly, the FDA in the United States and similar bodies in Europe prefer quantitative information of this sort.

Fig. 3.

How RPPA can be used as a calibrated immunoassay able to classify a given patient value above or below a predetermined cutoff point using low and high controls and a calibration curve.

Once quantitative data has been obtained from the large sample sets available on the RPPA platform, the next step is to use conventional statistical and bioinformatic protocols to determine how specific the RPPA-based discrimination is between patients and controls. For single analytes, the approaches are routine. However, multiple analytes, of individually marginal significance, can potentially be combined to generate much better signals using simple ratios or more complex pathway analysis (98). This is especially true for ratios if one signal is elevated and the other is reduced. Composites of multiple analytes can also be deployed to assess more complex relationships. In all cases, receiver operating condition curves, an absolute requirement in the pharmaceutical industry for validation of an assay, can unambiguously identify problems with false negative and false positive signals (71, 98).

Matrix Effects on RPPA Output

The medium that the patient analyte is suspended in is termed the matrix, and it can have substantial effects on the values obtained from an analysis because of nonspecific primary and secondary affinity reagent (antibody) binding, epitope masking, and effects on spot morphology. Thus, it is important to print patient samples and standards/calibrators in a common matrix. Plasma, for example, has its own consequence for standard curves that is different from those for other biological fluids such as serum, cerebrospinal fluid, or urine (71). Some investigators are utilizing new sample processing and analyte-enrichment approaches including nanoparticle-based biomarker “harvesting” techniques to reduce matrix effects and concentrate analytes into the linear dynamic range of RPPA and other immunoassay formats (99). However, this can introduce additional challenges regarding things such as the completeness of the concentrating approach, as well as changes in the matrix that will then be unique to whatever solution is used to generate the sample. These concerns require replication of the enrichment process with standards. Importantly, different standards, in their own matrices, should be printed on the same RPPA slides, so that the entire analysis can be performed without the need for sample-specific RPPA slides.

Patients and “Controls”

The identification of a disease- or treatment-specific signal depends on the proper choice of control patients who do not have the disease or treatment of interest. The term “control patient” is intended to emphasize the obvious, as there is no such thing as a control human who is actually “normal.” Simply scrutinizing the ranges said to be “normal” in conventional clinical chemistry will immediately show this to be true. In addition, the variance of signals from the patients will often be much tighter than the variance of signals from the control patients. This is because the disease-specific patients may have more in common than a collection of people who can be included in the non-disease-specific category. Many statistical approaches depend on the assumption of a common variance in the samples being compared. Clinical statisticians can give advice on how to address this problem. Finally, examining the entire dataset from the vantage point of the hierarchical clustering algorithm will often identify subcategories of patients, both diseased and control, that had previously been expected to be homogeneous (14, 35).

Patient Samples and Sources of Error

As with any other clinical immunoassay such as ELISA or IHC, the quality of the output from an RPPA platform is only as good as the quality of the samples provided. Careful consideration must be given to preanalytical variables; therefore, the workflow for RPPA applications to clinical samples must begin at the point of procurement of the sample. Biopsy samples that sit at room temperature for variable (or sometimes unknown) periods of time may allow the analyte of interest to be degraded by proteases or a post-translational modification such as phosphorylation to be modified, either through degradation by phosphatases or, somewhat unexpectedly, activation by kinases. Recent literature has revealed the lability of the proteome and phosphoproteome due to preanalytical variables such as intraoperative hypoxia, post-excision delay times, tissue processing times, etc. (100–103). Formalin penetrates at 1 mm/h, providing ample time for many proteins to change in the hypoxic, acidotic tissue environment of the wounded tissue sample before it is properly fixed or frozen. Because many clinical sites lack the ability to snap-freeze tissue, new types of rapidly penetrating tissue fixatives are being developed to provide formalin-like histomorphology concomitant with protein/phosphoprotein preservation equivalent to that of snap-frozen tissue. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of sources of error that begin before the RPPA is ever printed. Depending on the intended use of the RPPA application, up-front cellular enrichment might be required for accurate protein quantitation of a target analyte in particular cell populations in patient material. Techniques such as laser capture microdissection have been shown to be critical for obtaining accurate information concerning the quantitative values of a given signaling protein in particular cell populations in heterogeneous tissue samples (15, 35, 104). Many of the new molecular targeted therapies are directed against hyperactivated protein signaling networks, and many of the drug targets within the implicated networks such as PI3K-AKT, RAS-ERK, JAK-STAT, etc. are expressed in both tumor epithelium and stromal compartments (endothelial cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, etc.) in a tumor biopsy. Furthermore, it is now apparent that marked intratumoral heterogeneity in genomic aberrations can occur and be spatially constrained. Thus, an ability to assess different areas of a given tumor might provide additional information not available from analysis of the whole tumor. RPPA is extremely well positioned to serve as a powerful companion diagnostic technology that could potentially determine changes in signaling or other molecules in particular cell populations or specific areas in a tumor. As we identify means of stratifying patients based on the underpinning molecular signatures of their tumors and measure these drug target activities, the absolute onus is on us to get the measurement right. In order to properly transition the RPPA from a research-oriented clinical technology to a CLIA/College of Academic Pathologists–complaint/certified format, different workflows will need to be devised and implemented.

RPPA as a Clinical Laboratory Technique

One goal for RPPA technology is its implementation as a routine clinical laboratory test. In the United States, this means that the product must be compatible with the CLIA regulatory standards that are applied to all clinical laboratory testing using approaches approved by the College of Academic Pathologists. Other countries have similar regulations to ensure that test results, no matter where or when the tests are performed, will be the same in terms of accuracy, reliability, and timeliness. Accuracy is codified in the cv. For RPPAs performed in the most experienced academic laboratories, between-array cv values of 5% to 6% are frequently observed (31, 71, 91). Clinical assays generally require cv values of 15% or less. This suggests that the RPPA platform has the intrinsic capability to be routinely implemented in a clinical laboratory as opportunities and needs arise. The combination of exquisite analytical sensitivity and clinical-grade accuracy should not be surprising given the background philosophical pedigree of the RPPA. As RPPA is essentially a micro/nanodot-blot technique that has a number of FDA predicates, utilizes FDA-cleared IHC devices for staining that are routinely found in CLIA-certified pathology and clinical laboratories, and uses analyte amplification from FDA-approved kits (e.g. Dako CSA for HercepTest™), the format is highly amenable to CLIA-compliant/accredited laboratories. By using predetermined cutoff points, highly trained personnel, and written standard operating procedures and by tracking all possible sources of variability, recent clinical trials for metastatic colorectal and breast cancer have shown that RPPA can be applied in a clinical laboratory setting (48).

Implementation of RPPA as a Clinical Diagnostic/Prognostic Tool for Personalized Healthcare

Because of RPPA's ability to quantitatively measure the functional activation state of a broad number of drug targets from clinical material, a growing number of investigators are implementing the technology as a clinical diagnostic and/or prognostic tool (35, 48). The development of a rapidly growing cadre of targeted therapeutics, each with its own predictive companion diagnostic marker set, heralds a not-too-distant future wherein tissue-based analysis will expand beyond the measurement of a handful of tissue markers (e.g. HER2, ALK, ER, etc.) to a clinical reality in which panels of dozens to hundreds of specific markers will need to be quantitatively measured at once. Measuring such large panels of proteins and phosphoproteins will not be possible with immunohistochemical analysis, as this approach, even in multiplex, requires more tissue than is practically obtainable in a clinical setting—especially with fine needle aspirates and core needle biopsies, which underpin most personalized therapy-based workflows. In contrast, the RPPA platform is especially and uniquely well suited for such a task (105). Moreover, such assays may combine prognostic with predictive markers whereby a tissue biopsy sample is used to determined disease outcome risk (e.g. high-risk recurrence versus low-risk recurrence) and at the same time provide a molecular rationale to stratify high-risk subjects to tailored therapy. Such efforts have been recently posited for diseases such as node-negative lung cancer (94). Recently, the RPPA technology was successfully implemented to uncover a new phenotype of breast cancer wherein the patients were found to have activated HER2 signaling (phosphorylated HER2) in the absence of FISH/IHC positivity (35). This finding has been subsequently validated by others (106) and is underpinning evaluation of patient selection by HER2 phosphorylation status.

Integration of RPPA data with other genomic, metabolomic, lipidomic, and drug sensitivity sets will inevitably provide additional insight into disease and drug mechanism studies. RPPA analysis of the activation state of proteins will provide an additional function context for genomic mutation and variant analysis data. A recent study published by the Cancer Genome Atlas Network applied multivariate statistical analysis to a combined dataset consisting of RPPA, genomic DNA copy number, DNA methylation, exome sequencing, mRNA arrays, and microRNA analysis of breast cancer patient biopsies (107). Broadscale multi-omic integration of RPPA phosphoprotein and protein data along with genomic, metabolomic, and other data types has been recently utilized across the NCI-60 cell line set (95). Thus the integration of RPPA proteomic data with other omic datasets is well positioned to provide novel insights and enhance the value of any single omics approach. However, significant bioinformatics challenges in defining how to best integrate orthogonal datasets remain to be resolved. Data integration and the development of user-friendly software tools to support robust bioinformatic and statistical analysis of combined omics data are key priorities for future development.

RPPA Platform of the Future

Future technologic advances can be envisioned that will simplify the RPPA workflow, reduce the complexity of the assay steps, and render a direct quantitative output. The basic advantages of the RPPA concept that are likely to be retained in any future version of the technology are as follows:

Antigen-down configuration: The analyte antigen is immobilized on a solid phase with high protein binding capacity per unit area. Only one type of primary antibody is required for antigen recognition, obviating the need for an antibody sandwich pair. This attribute also vastly expands the repertoire of antibodies to include any specific anti-peptide antibody.

Miniaturization and multiplexing: Hundreds of different analytes can be measured with very high sensitivity and precision from a starting sample volume of only 20 μl. This is an extremely competitive aspect of the technology, particularly in dealing with patient samples for which earlier diagnostics have resulted in less material being available for analysis.

Beyond these basic constraints, a major target of RPPA technology improvement would be to eliminate the need for image capture and image analysis of the stained array. We can imagine an RPPA platform of the future in which the quantitative readout is done automatically for each array spot. In this future version of the technology, the array slides are loaded into a reader and the data are generated immediately, without the need for fluorescence or colorimetric staining and image capture. Two classes of emerging technologies offer means to generate a direct readout. The first is MALDI using isotope-labeled antibodies or antibodies with mass tags. The second is nanosensor technology that employs amperometric sensing of enzyme tags. Both of these approaches are under development in RPPA labs. We can speculate that within the next few years a fully automated clinical-grade RPPA platform will exist that can take an input sample from a body fluid, cell lysate, or microdissected tissue sample and directly read out the quantitative results for hundreds of analytes.

Final Conclusions: Current Limitations and Future Directions to Advance the Field

RPPA represents a rapidly emerging and advancing cost-effective technology that is able to quantitatively analyze hundreds of proteins and post-translational modifications at low levels in small samples. Although mass spectroscopy approaches hold great promise for the analysis of samples, they do not currently have the throughput, sensitivity, ability to deal with small amounts of material, or cost effectiveness of the RPPA platform. However, one of the limitations of the RPPA platform is that, like other antibody-dependent technologies (e.g. ELISA, forward phase array, bead capture assay, immunohistochemistry), the platform is inherently less of a de novo discovery platform, such as mass spectrometry, and more of a profiling/highly multiplexed clinical immunoassay in which the targets are known ahead of time. One of the special attributes of the RPPA platform is its unparalleled ability to measure a large number of low-abundance signaling proteins/phosphoproteins from a small amount of input material. Typical clinical applications using 10,000 to 20,000 laser capture microdissected cells can be used to generate quantitative data via RPPA for 100 to 150 signaling proteins (94, 108). The analytical sensitivity of RPPA has been evaluated by a number of investigators who have reported the lower limits of detection as in the fg/ml range, with linearity in the sub-pg/ml range (91, 109), which is more than several orders of magnitude more sensitive than current multiple reaction monitoring lower limits of detection (110, 111).

RPPA has been shown by many investigators to generate linear quantitative data from as little as a single cell equivalent and a few thousand molecules per “spot” (91, 109). Recent reviews have discussed more thoroughly the analytical sensitivity comparisons between RPPA and other immunoassay measurement techniques (105). In contrast to RPPA, MS-based analysis does not rely on a priori knowledge about the target or the availability of high-quality antibodies, can measure many types of post-translational modifications, and does not rely on an antibody for detection. However, MS has very poor analytical sensitivity relative to immunoassays, including RPPA. This deficiency limits the utility of MS for clinical biomarker measurement. Based on the strengths and limitations of the two approaches, a highly synergic workflow could be established wherein MS analysis is used for up-front de novo target discovery and immunoassay techniques such as RPPA are used in clinic and research settings for high-throughput protein/multiplexed validation and profiling.

The RPPA platform has demonstrated utility in the characterization of cell lines, animal models, and patient samples, including for the clinical management of patients. The power of the technology is manifest at least in part in the hundreds of publications using and evaluating the RPPA technology identified in a scan of Medline. This makes a community-wide effort to define and share information on hardware, software algorithms, and analytical challenges and limitations critical in order for the promise of the platform to be realized in discovery and clinical research. Although establishing best practices is important for discovery research and hypothesis validation, the opportunity and, indeed, the need to implement RPPA into patient care in a CLIA or GLCP environment requires a much higher standard of validation.

Although the RPPA technology has unmatched attributes when it comes to multiplexed protein analysis of small amounts of clinical samples and large numbers of samples, there are numerous aspects of the technique that have the potential for improvement that could allow those in the field to more fully capitalize on the platform.

The platform is critically dependent on high-quality affinity reagents. A concerted effort by academia and industry has resulted in a rapid increase in high-quality affinity reagents, greatly facilitating the implementation and utility of RPPA. However, the effort and approaches needed for validation and revalidation of affinity reagents remain perhaps the greatest challenge and opportunity for a concerted community effort. It is important to emphasize that the unique characteristics of RPPA require greater specificity and different antibody characteristics than many other approaches. Indeed, once the initial repertoire of high-quality antibodies is exhausted, the validation rate for new targets and antibodies will probably be in the range of 20%. Thus the commitment from the RPPA Workshop participants to share antibody lists and validation approaches is critical to cost containment and to democratizing the technology platform.

As the amount of high-quality data generated on the RPPA platform is rapidly increasing, it is becoming possible to consider the generation and dissemination of a “Human Proteomics Atlas” that would both complement and extend the utility of similar genomics efforts. This will require the development of a centralized user-friendly data repository for RPPA data storage and sharing, similar to those existing for gene expression profiling. RPPA data have already been hosted on several of the publicly available cancer genomics data portals, such as the University of California Santa Cruz Cancer Genomics Browser (112, 113), the MSKCC cBio portal (114), and the Cancer Genome Atlas portal. Beyond the importance of sharing RPPA data, these data portals are of great interest for their capacity to integrate data from different sources, such as RPPA, phenotype, gene expression, copy number, mutation status, small molecules, and drug sensitivity data (95, 115). In this manner, the RPPA technology will provide a tremendous contribution to systems biology modeling of cancer based on network models. These annotated network models allow better understanding of genomic drivers and identify new protein biomarkers and drug targets. These types of data-mining and pathway-network building tools provide unique opportunities to develop interomic data “stitching” and a systems network view of biology that could enable a much deeper understanding of diseases such as cancer.

New uses for RPPA—for example, in drug screening; systems biology; and the analysis of subcellular fractions, serum, and plasma—will require flexible approaches and platforms. Thus, although high-quality best practices should be shared across the community, the platform needs to remain flexible with the ability to rapidly adapt to emerging opportunities. At this point, reporting conventions such as MIAME, MIAPE, MIARE, and MISFISHIE and validation approaches such as REMARK and BRISQ are likely too rigid for current implementation; however, at some point the platform would benefit from reporting requirements and even standardized best practices as they emerge. The development of shared reference material and standards would be especially useful to the RPPA community.