Abstract

The evolution of cancer therapy into complex regimens with multiple drugs requires novel approaches for the development and evaluation of companion biomarkers. Liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry (LC-MRM) is a versatile platform for biomarker measurement. In this study, we describe the development and use of the LC-MRM platform to study the adaptive signaling responses of melanoma cells to inhibitors of HSP90 (XL888) and MEK (AZD6244). XL888 had good anti-tumor activity against NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines as well as BRAF mutant cells with acquired resistance to BRAF inhibitors both in vitro and in vivo. LC-MRM analysis showed HSP90 inhibition to be associated with decreased expression of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases, modules in the PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway, and the MAPK/CDK4 signaling axis in NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines and the inhibition of PI3K/AKT signaling in BRAF mutant melanoma xenografts with acquired vemurafenib resistance. The LC-MRM approach targeting more than 80 cancer signaling proteins was highly sensitive and could be applied to fine needle aspirates from xenografts and clinical melanoma specimens (using 50 μg of total protein). We further showed MEK inhibition to be associated with signaling through the NFκB and WNT signaling pathways, as well as increased receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activation. Validation studies identified PDGF receptor β signaling as a potential escape mechanism from MEK inhibition, which could be overcome through combined use of AZD6244 and the PDGF receptor inhibitor, crenolanib. Together, our studies show LC-MRM to have unique value as a platform for the systems level understanding of the molecular mechanisms of drug response and therapeutic escape. This work provides the proof-of-principle for the future development of LC-MRM assays for monitoring drug responses in the clinic.

Despite excitement about the development of targeted therapy strategies for cancer, few cures have been achieved. In patients with BRAF mutant melanoma, treatment with small molecule BRAF inhibitors typically follows a course of response and tumor shrinkage followed by eventual relapse and resistance (mean progression-free survival is ∼5.3 months) (1). Resistance to BRAF inhibitors is typically accompanied by reactivation of the MAPK signaling pathway, an effect mediated through activating mutations in NRAS and MEK1/2, genomic amplification of BRAF, increased expression of CRAF and Cot, and the acquisition of BRAF splice-form mutants (2–5). There is also evidence that increased PI3K/AKT signaling, resulting from the genetic inactivation of PTEN and NF1 and increased receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)1 signaling, may be involved in acquired BRAF inhibitor resistance (5–7). Many of the signaling proteins implicated in the escape from BRAF inhibitor therapy are clients of heat shock protein (HSP)-90 (8). Preclinical evidence now indicates that HSP90 inhibitors can overcome acquired and intrinsic BRAF inhibitor resistance, and clinical trials have been initiated to evaluate the BRAF/HSP90 combination in newly diagnosed patients (8, 9).

Although targeted therapy strategies have been promising in BRAF mutant melanoma, few options currently exist for the 15–20% of melanoma patients whose tumors harbor activating NRAS mutations (10). Although there is some evidence that MEK inhibitors have activity in NRAS mutant melanoma patients, responses tend to be short-lived (mean progression-free survival ∼3 months) and resistance is nearly inevitable (11). Our emerging experience suggests that oncogene-driven signaling networks are highly robust with the capacity to rapidly adapt (12, 13). The future success of targeted therapy for melanoma and other cancers will depend upon the development of strategies that identify and overcome these adaptive escape mechanisms.

The evaluation of targeted therapy responses in patients has proved to be challenging. The clinical development of HSP90 inhibitors has been hampered in part by the lack of a good pharmacodynamic assay for measuring HSP90 inhibition within tumor specimens (14). Additionally, very little is known about the adaptive changes that occur following the inhibition of MEK/ERK signaling in NRAS mutant melanoma. To address these issues, the optimal technique is liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry, which been shown to be highly reproducible and portable across laboratories (15–18).

In addition to these technical developments, LC-MRM has also been shown to have excellent application to the study of biological pathways, including phosphotyrosine signaling, β-catenin signaling in colon cancer, and the evasion of apoptosis following BRAF inhibition in PTEN null melanoma (19–21). This technique can also be readily translated from cell line models to patient specimens. Here, we have developed a novel multiplexed LC-MRM assay to quantify the expression of >80 key signaling proteins in cell line models and fine needle aspirates from accessible melanoma lesions (22). In this study, we present the proof-of-principle for monitoring multiple signaling proteins in melanomas treated with either HSP90 or MEK inhibitors. Through this method, we identify the degradation of key HSP90 client proteins in vivo and elucidate a novel mechanism of adaptation to MEK inhibition through increased RTK signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and MTT Assay

WM1361A, WM1366, and WM1346 melanoma cell lines were a kind gift from Dr. Meenhard Herlyn (The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA), and M318 and M245 cell lines were a gift from Antoni Ribas (UCLA, Los Angeles, CA). All cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% FBS. MTT assays were performed as described previously (15).

LC-MRM Analysis of HSPs and Cancer Signaling Proteins

HSPs were quantified from digests of whole cell lysates; protein extracts from ∼2,000 cells (200 ng of total protein digest) were analyzed with LC-MRM after denaturation with 8 m urea, reduction, alkylation, and in-solution digestion.

The GeLC-MRM approach to quantify lower abundance cancer signaling proteins was developed based on previous implementations of SDS-PAGE fractionation combined with LC-MRM quantification (22–25). From each cell lysate or tissue homogenate, an aliquot of protein extract (50 μg) was fractionated by SDS-PAGE into five regions of 4–12% BisTris gels (Criterion XT, Bio-Rad) and visualized with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 (Aldrich), as described in supplemental Fig. 1. The approximate molecular weight ranges are as follows: band 1, >250 kDa; band 2, 120–250 kDa; band 3, 70–120 kDa; band 4, 30–70 kDa; and band 5, <30 kDa. Gel regions were excised and diced (to ∼1 mm3) for processing. After destaining, cysteines were reduced with 2 mm tris(carboxyethyl)phosphine and alkylated with 20 mm iodoacetamide prior to overnight digestion with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI). The resulting proteolytic peptides were extracted with aqueous 50% acetonitrile, 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid and concentrated vacuum centrifugation (SC210A, Speedvac, Thermo). Peptides were resuspended in 2% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (loading solvent), containing the internal standards.

LC-MRM analysis was performed in triplicate on a nanoLC (EasynLC, Proxeon, Thermo, San Jose, CA) interfaced with an electrospray triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (TSQ Quantum Ultra or Vantage, Thermo, San Jose, CA). The following solvent system is used for LC-MRM analysis; solvent A is aqueous 5% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, and solvent B is aqueous 90% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. For each sample, an aliquot of the peptide mixture (5 μl, ∼1/6 of the sample) was loaded onto the trap column at 6 μl/min and washed with loading solvent for 5 min. Then, a gradient of 5% B to 50% B was applied over 35 min prior to washing the column and re-equilibrating over a total of 45 min for the LC experiment. Mass spectrometry instrument parameters include the following: 2400-V spray voltage; 250 °C transfer tube temperature; Q1 resolution 0.4 when transitions were monitored for the entire LC separation (HSPs and band 1) and 0.7 when scheduled methods were used (bands 2–5); 1.5 millitorr collision gas pressure; Q3 resolution 0.7; and 20-ms scan time per transition. The list of proteins, peptides, and transitions is given in supplemental Table 1. Briefly, the number of peptides and transitions for each gel band ranged from band 1 with six peptides and 30 transitions to band 3 with 68 peptides and 252 transitions. Collision energy values were optimized by infusion of the standard peptides.

Skyline version 1.3 was used for data evaluation (26). Peaks were evaluated by comparison of their elution time and fragment ion signal ratios to their matched internal standards. All transitions above 10% of the base peak were used for quantification. Data were exported to Excel for calculations of protein quantity, standard deviation, and column volumes (%).

Western Blotting and Phospho-RTK Array

Melanoma cells were treated with either 300 nm XL-888 for up to 48 h or with 1 μm AZD6244 for 24 h before protein lysate was collected and run on 8–16% Tris/glycine gels. Proteins were subsequently immunoblotted with the antibodies to AKT1, APC, phospho-NFκB (Ser-536), mTOR, phospho-AKT (Ser-473), CDK4, PDGFR-β, EGF receptor, c-MET, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and IGF-1Rβ, which were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The β-catenin antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences, and GAPDH was purchased from Sigma. WM1361A and WM1366 cells were treated with 1 μm AZD6244 for 24 h, and the lysate collected was used for phospho-RTK arrays, which were carried out using the phospho-RTK kit from R&D Systems (catalog no. ARY001B), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were plated into 6-well tissue culture plates at 60% confluence and left to grow overnight before being treated with either 1 μm AZD6244 alone, 1 μm crenolanib or the combination of AZD6244 and crenolanib for 120 h before being harvested. In other studies, cells were treated with β-catenin siRNA followed by treatment with either vehicle or AZD6244. Annexin-V staining was performed as described previously (19), and apoptosis was assessed via flow cytometry.

Xenograft Studies and Human Tumor Acquisition

Animal experiments were conducted under a protocol approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IS0000324). BALB SCID mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were subcutaneously injected with 2.5 × 106 cells per mouse (resuspended in 111 μl of L-15 media, 10 mm HEPES, 37.5 μl Matrigel). Tumors were grown to ∼100 mm3 prior to dosing. Mice were treated with either 100 mg of XL888/kg (n = 5) or an equivalent volume of vehicle (10 mm HCl), three times per week by oral gavage. Mouse weights and tumor volumes (L × W2/2) were measured three times per week. Upon completion of the experiment, vehicle and drug-treated tumor biopsies were processed for LC-MRM analysis (as above). Human specimens were procured in the operating theater by fine needle aspiration of resected tumors under a protocol approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board (MCC number 15375); samples were transferred on ice and processed immediately for GeLC-MRM analysis for an exploratory study in the feasibility of assay transfer from preclinical models.

Colony Formation

WM1366 and WM1361A cells were treated with either 1 μm AZD6244 alone, 1 μm crenolanib alone, or the combination of AZD6244 and crenolanib twice a week for 4 weeks before being fixed in crystal violet and quantified.

β-Catenin siRNA

WM1366 cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% FBS and plated 200,000 cells per well in a 6-well plate and allowed to adhere overnight. The next day, the media were aspirated, and wells were washed with 1 ml of Opti-MEM and replaced with 1 ml of Opti-MEM. Cells were transfected with 50 nm β-catenin siRNA (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) or 50 nm scrambled RNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) with Lipofectamine, according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 24 h of transfection, wells were supplemented with RPMI 1640 medium, FBS, and/or AZD6244 to make a final concentration of 5% FBS in the wells and a final concentration of 1 μm AZD6244 for MEKi-treated wells. Lysate was created after 24 h of exposure to AZD6244, and Western blotting was performed to analyze β-catenin knockdown efficiency and the associated effects upon pERK, ERK, cyclin B1, and cyclin D1. GAPDH was used as the loading control.

Statistical Analysis

Data show the mean of at least three independent experiments. GraphPad Prism 5 statistical software was used to perform the Student's t test, where * indicates p ≤ 0.05; ** indicates 0.05 ≤ p ≤ 0.01; *** indicates p ≤ 0.001, and **** indicates p ≤ 0.0001.

RESULTS

Assay Workflow and Outline of the Signaling Scheme Interrogated by the Assay

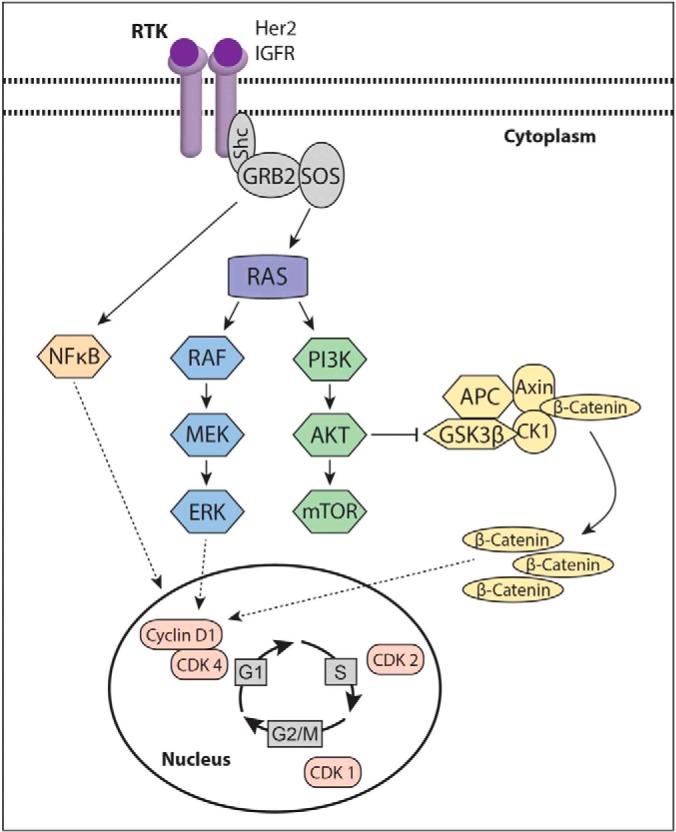

An LC-MRM assay was designed to capture all of the HSP family of chaperones and a series of 81 proteins in multiple signaling pathways known to be important for melanoma progression and resistance to targeted therapies. Pathways and processes covered included the cell cycle (CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, cyclin D1, and CHK1), receptor tyrosine kinases (ERBB2 and IGF1R), RAS/MAPK signaling (NRAS, HRAS, KRAS, SOS1, SHC1, BRAF, ARAF, CRAF, MEK1/2, and c-Myc), PI3K/AKT signaling (AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, mTOR, CSK, FAK1, and GSK3β), β-catenin/WNT signaling (APC, axin, β-catenin, and α-catenin), NFκB, Src, and MITF (signaling scheme is shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Scheme showing the signaling nodes covered by the LC-MRM assay.

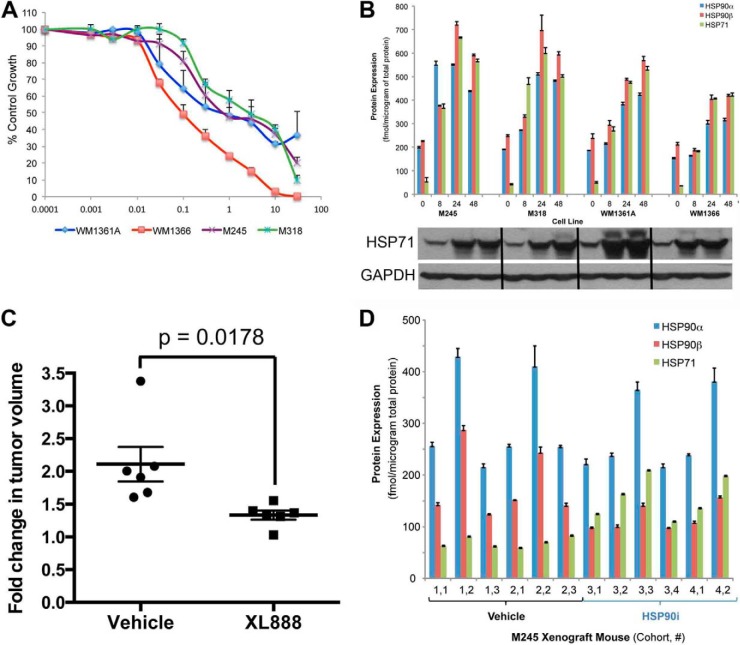

HSP90 Inhibition Is Associated with Induction of HSP70 in Vitro and in Vivo

Inhibition of HSP90 is known to be associated with compensatory increases in the expression of the highly abundant chaperone protein HSP70. We began using the LC-MRM platform to analyze the altered expression of chaperones following treatment with HSP90 inhibitor. Increasing concentrations of the HSP90 inhibitor XL888 led to concentration-dependent decreases in the growth of four NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines (M245, M318, WM1361A, and WM1366) (Fig. 2A). In the four cell line models, XL888 (300 nm) induced the expression of HSP70 isoform 1 (HSP71), HSP90α, and HSP90β as measured by LC-MRM (Fig. 2B). Western blot studies confirmed the increases in HSP71 (Fig. 2B). In a second series of experiments, NRAS mutant M245 melanoma cells were grown as xenografts in SCID mice. After tumors were palpable, treatment with XL888 (125 mg/kg) was initiated for 15 days, with drug treatment being associated with significant decreases in tumor volume (p < 0.02) (Fig. 2C). LC-MRM analysis of tumor specimens harvested on treatment showed increased levels of HSP70 isoform 1 expression compared with vehicle controls (Fig. 2D). Total expression levels (in femtomoles/μg total protein) are lower in tumors than the cell line models due to the amounts of protein contributed by the stroma and blood in the mouse tissue.

Fig. 2.

LC-MRM detects increased HSP70 expression following treatment with the HSP90 inhibitor XL888. A, XL888 is associated with concentration-dependent decreases in cell growth in NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines. Four NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of XL888 for 72 h. Cell viability was measured using the Alamar Blue assay. B, LC-MRM quantification of HSP90α, HSP90β, and HSP70 isoform 1 (HSP71) induction following treatment of four NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines (M245, M318, WM1361A, and WM1366) with XL888 (300 nm, 0–48 h). Protein expression is shown in femtomoles/μg of total protein. C, in vivo efficacy of XL888. NRAS mutant M245 melanoma cells were grown as xenografts in SCID mice. Treatment with XL888 (100 mg/kg, daily) was initiated once tumors were palpable. Data show the tumor volume fold-change from baseline following treatment with either vehicle or XL888. D, LC-MRM analysis of HSP90α, HSP90β, and HSP71 expression following treatment with either vehicle or XL888. Protein expression is given as femtomoles/μg of total protein.

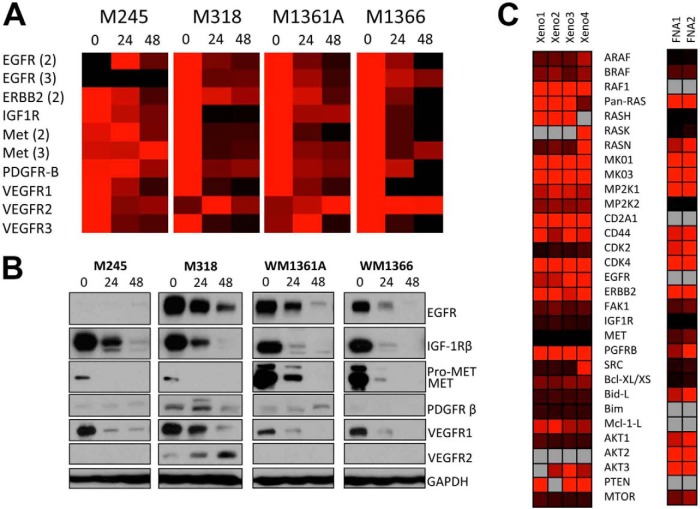

LC-MRM-mediated Detection of Client Protein Degradation in NRAS Mutant Melanoma

Over 200 proteins have been identified to be clients of HSP90 (27). The efficacy of HSP90 inhibitors is dependent upon the degradation of client proteins that are essential for tumor survival. As yet, no assays exist that enable multiple client proteins to be monitored simultaneously and evaluated in small clinical specimens. A panel of four NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines (M245, M318, WM1361A, and WM1366) were treated with XL888 (300 nm, 24 h), processed for GeLC-MRM, and analyzed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 3A). XL888 treatment led to a marked decrease in the expression of multiple RTKs, including EGF receptor, IGF-1Rβ, c-MET, and VEGFR1 (Fig. 3A). Unexpectedly, HSP90 inhibition increased expression of VEGFR2 (Fig. 3A). Western blot validation confirmed the decreases in client protein expression identified by LC-MRM, as well as the increased expression of VEGFR2 (Fig. 3B). As the availability of clinical material for analysis is often limited, we next determined whether the LC-MRM platform was sufficiently sensitive to measure the expression of client proteins in small samples of ∼50 μg of total protein, such as those available from fine needle aspirates. Proteins could be detected and quantified in fine needle aspirates taken from both human melanoma xenografts as well as from two melanoma specimens; heat maps are shown for selected proteins (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

LC-MRM detection of HSP client proteins. A, LC-MRM analysis of NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines following treatment with XL888. NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines were treated with XL888 (300 nm, 0–48 h) before being analyzed by LC-MRM. B, Western blot validation confirming decreased levels in RTK expression following XL888 treatment. C, heat maps of relative quantification of RTK expression in fine needle aspirates taken from xenografts of human melanoma cells and from two clinical melanoma specimens.

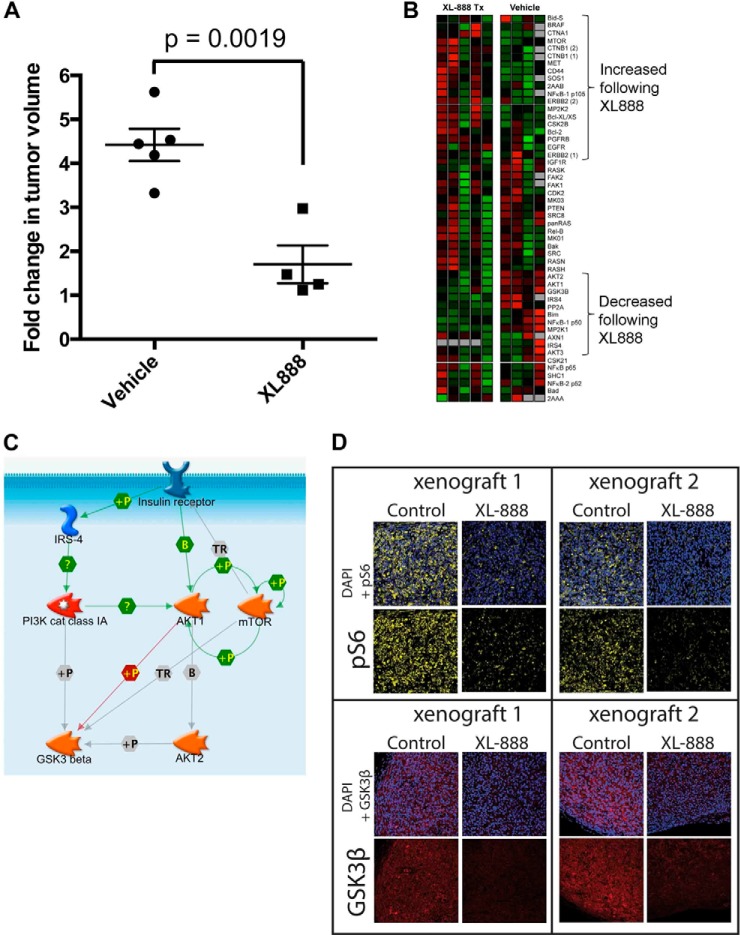

LC-MRM Detects Client Protein Expression and Client Protein Degradation in Vivo

Acquired resistance to BRAF inhibitors limits their long term use in advanced melanoma. HSP90 inhibition is one potential strategy to overcome acquired BRAF inhibitor resistance that our group is exploring clinically (NCT01657591). XL888 (125 mg/kg, p.o., daily) significantly reduced the growth of vemurafenib-resistant 1205LuR melanoma cells xenografted onto SCID mice (Fig. 4A). LC-MRM analysis of specimens from tumor specimens collected following 15 days of XL888 therapy showed significant decreases in the expression of proteins in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, including mTOR, IRS-4, GSK3β, and AKT1/2 (Fig. 4B; signaling pathway illustrated in Fig. 4C). Immunohistochemical staining of matched specimens from vehicle and XL888-treated mice confirmed the LC-MRM data. HSP90 inhibition decreases GSK3β expression and results in inhibition of mTOR signaling, as shown by reduced staining for phospho-Ser-6 (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

LC-MRM as a platform for the detection of decreased HSP client expression in an in vivo model of acquired vemurafenib resistance following XL888 treatment. A, treatment of M229R vemurafenib-resistant xenografts with XL888 leads to significant levels of tumor shrinkage in vivo. M229R cells were allowed to form palpable xenografts, before treatment was initiated with either vehicle or XL888. Data show fold change from baseline after 14 days of treatment. B, LC-MRM analysis of xenograft specimens treated with either vehicle or XL888. C, LC-MRM quantification shows the decreased expression of proteins associated with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in XL888-treated xenografts. D, immunofluorescence staining demonstrating the loss of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in 1205LuR xenografts following XL888 treatment.

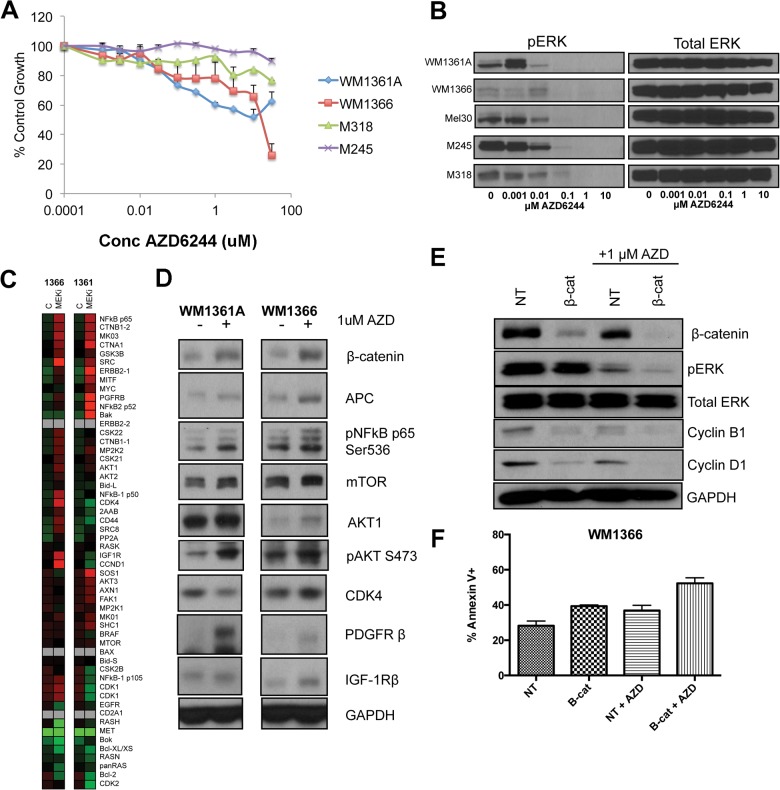

LC-MRM Analysis of Responses to MEK Inhibition Identifies Adaptive Signaling Nodes in NRAS Mutant Melanoma Cell Lines

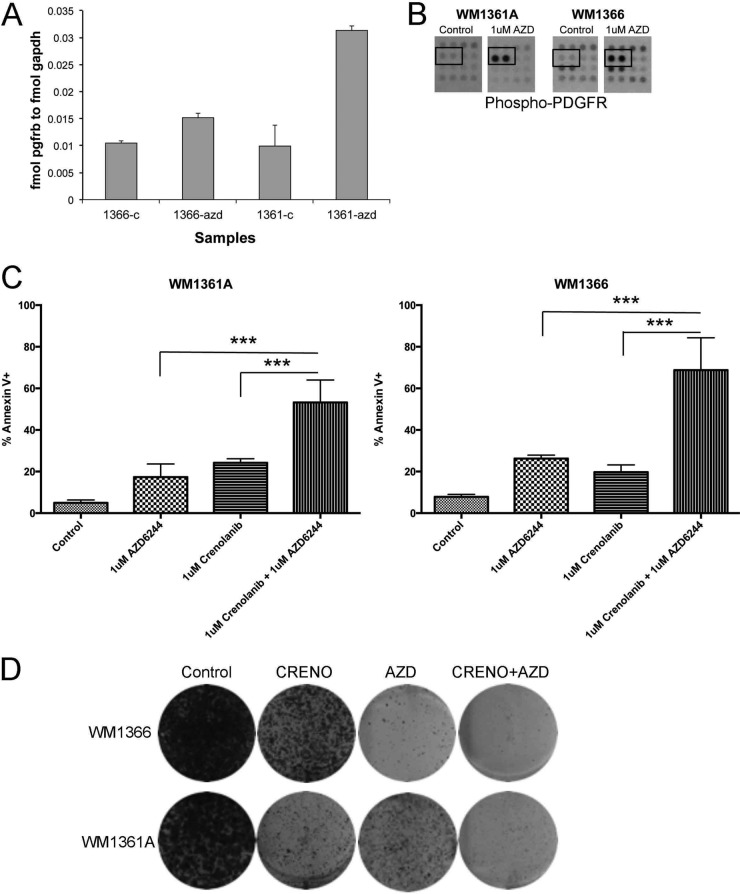

MEK inhibition is one strategy being investigated clinically for NRAS mutant melanoma. Treatment of NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines with the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 led to weak inhibitory effects upon cell growth (Fig. 5A) and was associated with inhibition of ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 5B). Because the concentrations of AZD6244 required to inhibit ERK signaling and cell growth were not well correlated, we used the LC-MRM platform to identify potential adaptive signaling mechanisms to MEK inhibition in two NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines (Fig. 5C). It was noted that AZD6244 treatment was associated with a signature associated with increased WNT signaling (increased β-catenin and APC expression), the increased phosphorylation of the NFκB p65 subunit, and an enhancement of PDGFR-β expression (Fig. 5, C and D). Functional studies showed a potential role for WNT signaling in therapeutic escape, with siRNA knockdown of β-catenin being found to cooperate in the down-regulation of pERK and cyclin D1 expression following AZD6244 treatment (Fig. 5E). There was also evidence that β-catenin knockdown slightly enhanced AZD6244-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5F). Further analysis showed increased PDGFR-β expression to be paralleled by enhanced signaling, with LC-MRM and RTK arrays demonstrating AZD6244 to increase the level of expression of total and phosphorylated PDGFR-β (Fig. 6, A and B). Treatment of the WM1366 and WM1361A cell lines with the combination of AZD6244 and crenolanib (an RTK inhibitor that targets PDGFR signaling) significantly enhanced the level of apoptosis compared with either agent alone and prevented the outgrowth of drug-resistant colonies (Fig. 6, C and D).

Fig. 5.

LC-MRM quantification of adaptive signaling in NRAS mutant melanoma following MEK inhibition. A, MEK inhibitor, AZD62442, leads to concentration-dependent decreases in the growth of NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines. Cells were treated with AZD6244 for 72 h, and levels of growth inhibition were quantified using the MTT assay. B, AZD6244 inhibits MAPK signaling in NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines. NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of AZD6244 (1 nm to 10 μm) for 1 h. Western blots show phospho-ERK levels and total ERK expression. C, LC-MRM peptide quantification indicates altered expression of multiple proteins in WM1366 and WM1361A cells following AZD6244 treatment. D, Western blot showing increased expression of WNT signaling proteins (β-catenin/APC), NFκB, and RTKs. E, siRNA knockdown of β-catenin cooperates with AZD6244 to limit phospho-ERK and cyclin D1 expression. Western blot showing the effects of β-catenin knockdown ± AZD6244 (1 μm) upon the expression of phospho-ERK, total ERK, cyclin B1, and cyclin D1. GADPH levels confirm even protein loading. F, siRNA knockdown of β-catenin enhances the level of AZD6244-mediated apoptosis in WM1366 cells. Levels of apoptosis were analyzed by annexin-V binding and flow cytometry. 2AZD is AZD-6244 (MEK inhibitor). NT is non-targeting siRNA used as a vehicle control. APC stands for Adenomatous Polyposis Coli.

Fig. 6.

Co-targeting of MEK and PDGFR limits therapeutic escape. A, LC-MRM analysis of absolute PDGFR expression (in mol normalized to GAPDH expression in fmol) following MEK inhibition. B, RTK array analysis demonstrates increased phosphorylation of PDGFR-β following MEK inhibition. WM131A and WM1366 cells were treated with AZD6244 (1 μm, 24 h) and analyzed on RTK arrays. Data show increased tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGFR-β following AZD6244 treatment. C, PDGFR inhibition overcomes escape from AZD6244 therapy. WM1361A and WM1366 cells were treated with vehicle, AZD6244 alone, crenolanib alone, or AZD6244 + crenolanib for 72 h. Levels of apoptosis were analyzed by annexin-V binding and flow cytometry. D, PDGFR inhibition prevents escape from AZD6244 treatment in long term colony formation assays. WM1366 and WM1361A cells were treated with vehicle, AZD6244 alone, crenolanib alone, or AZD6244 + crenolanib twice weekly for 4 weeks. Colonies were visualized by staining with crystal violet; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide. *** indicates p values < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

To date, most attempts to personalize cancer therapy have relied upon the matching of small molecule kinase inhibitors to patients with tumors harboring defined oncogenic mutations. Examples where this approach has been successfully used include vemurafenib in BRAF mutant melanoma, imatinib in KIT mutant gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and crizotinib in EML4-ALK mutant lung cancer (1, 28, 29). In the majority of cases, initially impressive responses were followed by eventual treatment failure. To date, strategies to define mechanisms of acquired resistance have centered upon the genetic analysis (typically whole exome sequencing) of matched pairs of naive and resistant cell lines and patient specimens (30, 31). Although these approaches have proven to be useful in identifying mutations that convey acquired drug resistance, they have shed little light upon the mechanisms by which cancer cells adapt to kinase inhibitor treatment. Novel technologies that can assess multiple components of the proteome are therefore urgently needed to allow early drug responses to be modeled, thus allowing personalized drug combinations to be defined for each patient. LC-MRM allows the expression of multiple proteins to be quantified in relatively small biopsy specimens. We here provide two examples that demonstrate the utility of LC-MRM in defining adaptive signaling responses of melanoma cells to drug treatment.

The majority of proteins required for malignant transformation and maintenance of the oncogenic phenotype are clients of the HSP family of chaperones (32). The HSPs play a critical role in stabilizing and maintaining the conformational profiles of diverse proteins, including RTKs, kinases, among other things (33, 34). The ability to target multiple oncogenic pathways simultaneously through pharmacological inhibition of HSP90 function has made this an attractive target for drug development. Although there has been some success of HSP90 inhibitors in the single agent setting (such as in anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive lung cancer), clinical responses have generally been disappointing. Interest in the strategy has been renewed in light of the ability of HSP90 inhibitors to enhance the activity of targeted therapy agents. There is already evidence that HSP90 inhibitors overcome trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer patients whose tumors overexpress HER2 and can also potentiate the effects of proteasome inhibitors in treatment-refractory multiple myeloma (14, 35–38). The exact clinical context supporting the use of HSP inhibitors has been limited by the large numbers of potential client proteins as well as the discordance between the in vitro and in vivo effects of HSP90 inhibitors.

In melanoma, the HSP90 inhibitor, XL888, decreased the growth of cell lines harboring NRAS mutations as well as those with acquired BRAF inhibitor resistance. In both cell culture and xenograft studies, HSP90 inhibition was associated with the induction of another chaperone, HSP70. The detection of increased HSP70 was highly sensitive, with quantification possible on as little 2,000 cells. There is evidence that induction of HSP70 compensates for inhibition of HSP90 function, and it may constitute a resistance mechanism to HSP90 inhibitors (39). Studies are currently underway to develop pharmacological inhibitors of HSP70, and there is preclinical evidence that co-targeting of HSP90 and HSP70 may be an effective therapeutic strategy (39–41). Although detection of increased HSP70 expression is often used as a biomarker of HSP90 inhibition in clinical studies, its induction occurs early and is not always well correlated with the anti-tumor activity of the drugs (36).

A more effective approach to monitor the efficacy of HSP90 inhibitors is through the quantification of the client proteins that are critical for maintaining the oncogenic phenotype. As our proof-of-principle, an LC-MRM assay was designed that incorporated tryptic peptides representing ∼80 proteins known to be critical for melanoma development and progression. Treatment of NRAS mutant melanoma cells with XL888 led to the time-dependent degradation of multiple RTKS. In this context, LC-MRM exhibited greater capability than Western blotting in terms of both the sensitivity of peptide detection and the ability to quantify expression changes following drug treatment. The future clinical utility of LC-MRM was demonstrated by the quantification of multiple cancer signaling proteins from melanoma xenografts as well as from fine needle aspirates taken from human melanoma specimens. The potential of this assay to measure pharmacodynamic responses to HSP90 inhibition was examined in xenografts of human melanoma cells with acquired vemurafenib resistance. Here, XL888 led to a significant reduction in tumor growth, with the LC-MRM assay demonstrating an unsuspected role for inhibition of signaling through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. In line with the predicted role of PI3K/mTOR in this model, the use of a combined PI3K/mTOR inhibitor was found to partly reverse acquired vemurafenib resistance. These observations agree with other recent studies implicating increased PI3K/AKT signaling to be a clinically relevant mediator of BRAF inhibitor resistance (6, 30, 42). These data give further weight to the future use of LC-MRM in the screening for HSP client proteins that may be the targets for other more specific kinase inhibitors.

As a final step, we determined whether the LC-MRM platform could be used to interrogate the adaptive signaling following kinase inhibition, which would demonstrate applicability in settings other than those like HSP inhibition, which involve regulation of protein expression. In agreement with previous work on BRAF mutant melanoma and triple negative breast cancer, MEK inhibition was found to up-regulate levels of RTK expression (12, 43, 44). In the case of the NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines studied, PDGFR-β, an RTK implicated in acquired BRAF inhibitor resistance, emerged as a candidate mediator of resistance (5). Although PDGFR-β was critical for therapeutic escape in this context, the expression of RTKs in melanoma is highly heterogeneous, and could be ultimately patient/tumor-specific. The multiplicity of RTK expression in melanoma cell lines and tumors is suggestive of many potential escape mechanisms and again underscores the need for multiplexed screening platforms such as the one described here (45, 46). With regard to the future clinical application of LC-MRM, a situation can be envisaged where the interrogation of adaptive RTK signaling could be used to design personalized, patient-specific MEK/RTK inhibitor combinations that limit the onset of resistance.

In addition to RTK up-regulation, increased expression and activation of components of the WNT, NFκB, and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways were also observed. There is already evidence that reciprocal up-regulation of AKT signaling, resulting from either loss of the negative pathway regulator PTEN or adaptive RTK signaling, can reduce responses to both BRAF and MEK inhibitors in melanoma cells. The potential role of WNT signaling in the response to MAPK pathway inhibitors in melanoma is more complex with recent studies showing the addition of WNT3A to enhance the cytotoxic activity of both AZD6244 in NRAS mutant melanoma cells and the BRAF inhibitor PLX4720 in BRAF mutant melanoma cells (47, 48). Here, we provide evidence that increased β-catenin expression following MEK inhibition may play a role in NRAS mutant melanoma cell survival through the maintenance of cyclin D1 expression. As yet, the potential role of increased NFκB signaling secondary to MEK inhibition has been little explored, but it could be representative of a further possible mechanism of escape.

In summary, we have described the development of a comprehensive new LC-MRM assay to measure adaptive signaling responses following targeted therapy in cancer, and we have given examples of its potential future utility. The further expansion, refinement, and validation of such assays will greatly aid the future elucidation of cancer biology as well as personalization of treatment for cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author contributions: V.W.R., E.R.W., A.S., G.T.G., V.K.S., J.M.K., and K.S.S. designed research; V.W.R., E.R.W., I.V.F., K.H.P., H.E.H., Y.C., and Y.X. performed research; Y.C., Y.X., and J.M.K. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; V.W.R., E.R.W., I.V.F., K.H.P., H.E.H., Y.C., Y.X., J.M.K., and K.S.S. analyzed data; V.W.R., E.R.W., A.S., G.T.G., V.K.S., J.M.K., and K.S.S. wrote the paper; A.S., G.T.G., and V.K.S. provided clinical support and insight.

* This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA161107-01, SPORE Grant P50 CA168536-01A, and Cancer Center Support Grant P30-CA076292 from the NCI. This work was also supported by Pilot Funding from the Department of Cutaneous Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center. The Moffitt Proteomics Facility is supported by the United States Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under Award W81XWH-08-2-0101 for a National Functional Genomics Center, and the Moffitt Foundation. The triple quadrupole mass spectrometer was purchased with a shared instrument grant from the Bankhead-Coley Cancer Research Program of the Florida Department of Health Grant 09BE-04.

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- LC-MRM

- liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry

- RTK

- receptor tyrosine kinase

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- HSP

- heat shock protein

- PDGFR

- PDGF receptor

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- APC

- adenomatous polyposis coli.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chapman P. B., Hauschild A., Robert C., Haanen J. B., Ascierto P., Larkin J., Dummer R., Garbe C., Testori A., Maio M., Hogg D., Lorigan P., Lebbe C., Jouary T., Schadendorf D., Ribas A., O'Day S. J., Sosman J. A., Kirkwood J. M., Eggermont A. M., Dreno B., Nolop K., Li J., Nelson B., Hou J., Lee R. J., Flaherty K. T., McArthur G. A. (2011) Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2507–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trunzer K., Pavlick A. C., Schuchter L., Gonzalez R., McArthur G. A., Hutson T. E., Moschos S. J., Flaherty K. T., Kim K. B., Weber J. S., Hersey P., Long G. V., Lawrence D., Ott P. A., Amaravadi R. K., Lewis K. D., Puzanov I., Lo R. S., Koehler A., Kockx M., Spleiss O., Schell-Steven A., Gilbert H. N., Cockey L., Bollag G., Lee R. J., Joe A. K., Sosman J. A., Ribas A. (2013) Pharmacodynamic effects and mechanisms of resistance to vemurafenib in patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 1767–1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fedorenko I. V., Paraiso K. H., Smalley K. S. (2011) Acquired and intrinsic BRAF inhibitor resistance in BRAF V600E mutant melanoma. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82, 201–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poulikakos P. I., Persaud Y., Janakiraman M., Kong X., Ng C., Moriceau G., Shi H., Atefi M., Titz B., Gabay M. T., Salton M., Dahlman K. B., Tadi M., Wargo J. A., Flaherty K. T., Kelley M. C., Misteli T., Chapman P. B., Sosman J. A., Graeber T. G., Ribas A., Lo R. S., Rosen N., Solit D. B. (2011) RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E). Nature 480, 387–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nazarian R., Shi H., Wang Q., Kong X., Koya R. C., Lee H., Chen Z., Lee M. K., Attar N., Sazegar H., Chodon T., Nelson S. F., McArthur G., Sosman J. A., Ribas A., Lo R. S. (2010) Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature 468, 973–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paraiso K. H., Xiang Y., Rebecca V. W., Abel E. V., Chen Y. A., Munko A. C., Wood E., Fedorenko I. V., Sondak V. K., Anderson A. R., Ribas A., Palma M. D., Nathanson K. L., Koomen J. M., Messina J. L., Smalley K. S. (2011) PTEN loss confers BRAF inhibitor resistance to melanoma cells through the suppression of BIM expression. Cancer Res. 71, 2750–2760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Whittaker S. R., Theurillat J. P., Van Allen E., Wagle N., Hsiao J., Cowley G. S., Schadendorf D., Root D. E., Garraway L. A. (2013) A genome-scale RNA interference screen implicates NF1 loss in resistance to RAF inhibition. Cancer Discov., 3, 350–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paraiso K. H., Haarberg H. E., Wood E., Rebecca V. W., Chen Y. A., Xiang Y., Ribas A., Lo R. S., Weber J. S., Sondak V. K., John J. K., Sarnaik A. A., Koomen J. M., Smalley K. S. (2012) The HSP90 inhibitor XL888 overcomes BRAF inhibitor resistance mediated through diverse mechanisms. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 2502–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu X., Marmarelis M. E., Hodi F. S. (2013) Activity of the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor ganetespib in melanoma. PLoS ONE 8, e56134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fedorenko I. V., Gibney G. T., Smalley K. S. (2013) NRAS mutant melanoma: biological behavior and future strategies for therapeutic management. Oncogene, 32, 3009–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ascierto P. A., Schadendorf D., Berking C., Agarwala S. S., van Herpen C. M., Queirolo P., Blank C. U., Hauschild A., Beck J. T., St-Pierre A., Niazi F., Wandel S., Peters M., Zubel A., Dummer R. (2013) MEK162 for patients with advanced melanoma harbouring NRAS or Val600 BRAF mutations: a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 14, 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lito P., Pratilas C. A., Joseph E. W., Tadi M., Halilovic E., Zubrowski M., Huang A., Wong W. L., Callahan M. K., Merghoub T., Wolchok J. D., de Stanchina E., Chandarlapaty S., Poulikakos P. I., Fagin J. A., Rosen N. (2012) Relief of profound feedback inhibition of mitogenic signaling by RAF inhibitors attenuates their activity in BRAFV600E melanomas. Cancer Cell 22, 668–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chandarlapaty S., Sawai A., Scaltriti M., Rodrik-Outmezguine V., Grbovic-Huezo O., Serra V., Majumder P. K., Baselga J., Rosen N. (2011) AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell 19, 58–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Richardson P. G., Chanan-Khan A. A., Lonial S., Krishnan A. Y., Carroll M. P., Alsina M., Albitar M., Berman D., Messina M., Anderson K. C. (2011) Tanespimycin and bortezomib combination treatment in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: results of a phase 1/2 study. Br. J. Haematol. 153, 729–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Addona T. A., Abbatiello S. E., Schilling B., Skates S. J., Mani D. R., Bunk D. M., Spiegelman C. H., Zimmerman L. J., Ham A. J., Keshishian H., Hall S. C., Allen S., Blackman R. K., Borchers C. H., Buck C., Cardasis H. L., Cusack M. P., Dodder N. G., Gibson B. W., Held J. M., Hiltke T., Jackson A., Johansen E. B., Kinsinger C. R., Li J., Mesri M., Neubert T. A., Niles R. K., Pulsipher T. C., Ransohoff D., Rodriguez H., Rudnick P. A., Smith D., Tabb D. L., Tegeler T. J., Variyath A. M., Vega-Montoto L. J., Wahlander A., Waldemarson S., Wang M., Whiteaker J. R., Zhao L., Anderson N. L., Fisher S. J., Liebler D. C., Paulovich A. G., Regnier F. E., Tempst P., Carr S. A. (2009) Multi-site assessment of the precision and reproducibility of multiple reaction monitoring-based measurements of proteins in plasma. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 633–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kennedy J. J., Abbatiello S. E., Kim K., Yan P., Whiteaker J. R., Lin C., Kim J. S., Zhang Y., Wang X., Ivey R. G., Zhao L., Min H., Lee Y., Yu M. H., Yang E. G., Lee C., Wang P., Rodriguez H., Kim Y., Carr S. A., Paulovich A. G. (2014) Demonstrating the feasibility of large-scale development of standardized assays to quantify human proteins. Nat. Methods, 11, 149–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prakash A., Rezai T., Krastins B., Sarracino D., Athanas M., Russo P., Zhang H., Tian Y., Li Y., Kulasingam V., Drabovich A., Smith C. R., Batruch I., Oran P. E., Fredolini C., Luchini A., Liotta L., Petricoin E., Diamandis E. P., Chan D. W., Nelson R., Lopez M. F. (2012) Interlaboratory reproducibility of selective reaction monitoring assays using multiple upfront analyte enrichment strategies. J. Proteome Res. 11, 3986–3995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prakash A., Rezai T., Krastins B., Sarracino D., Athanas M., Russo P., Ross M. M., Zhang H., Tian Y., Kulasingam V., Drabovich A. P., Smith C., Batruch I., Liotta L., Petricoin E., Diamandis E. P., Chan D. W., Lopez M. F. (2010) Platform for establishing interlaboratory reproducibility of selected reaction monitoring-based mass spectrometry peptide assays. J. Proteome Res. 9, 6678–6688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wolf-Yadlin A., Hautaniemi S., Lauffenburger D. A., White F. M. (2007) Multiple reaction monitoring for robust quantitative proteomic analysis of cellular signaling networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5860–5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen Y., Gruidl M., Remily-Wood E., Liu R. Z., Eschrich S., Lloyd M., Nasir A., Bui M. M., Huang E., Shibata D., Yeatman T., Koomen J. M. (2010) Quantification of β-catenin signaling components in colon cancer cell lines, tissue sections, and microdissected tumor cells using reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 9, 4215–4227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xiang Y., Remily-Wood E. R., Oliveira V., Yarde D., He L., Cheng J. Q., Mathews L., Boucher K., Cubitt C., Perez L., Gauthier T. J., Eschrich S. A., Shain K. H., Dalton W. S., Hazlehurst L., Koomen J. M. (2011) Monitoring a nuclear factor-κB signature of drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Mol. Cell. Proteomics, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Remily-Wood E. R., Liu R. Z., Xiang Y., Chen Y., Thomas C. E., Rajyaguru N., Kaufman L. M., Ochoa J. E., Hazlehurst L., Pinilla-Ibarz J., Lancet J., Zhang G., Haura E., Shibata D., Yeatman T., Smalley K. S., Dalton W. S., Huang E., Scott E., Bloom G. C., Eschrich S. A., Koomen J. M. (2011) A database of reaction monitoring mass spectrometry assays for elucidating therapeutic response in cancer. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 5, 383–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barnidge D. R., Goodmanson M. K., Klee G. G., Muddiman D. C. (2004) Absolute quantification of the model biomarker prostate-specific antigen in serum by LC-Ms/MS using protein cleavage and isotope dilution mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 3, 644–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gerber S. A., Rush J., Stemman O., Kirschner M. W., Gygi S. P. (2003) Absolute quantification of proteins and phosphoproteins from cell lysates by tandem MS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6940–6945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Havlis J., Shevchenko A. (2004) Absolute quantification of proteins in solutions and in polyacrylamide gels by mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 76, 3029–3036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. MacLean B., Tomazela D. M., Shulman N., Chambers M., Finney G. L., Frewen B., Kern R., Tabb D. L., Liebler D. C., MacCoss M. J. (2010) Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 26, 966–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taipale M., Krykbaeva I., Koeva M., Kayatekin C., Westover K. D., Karras G. I., Lindquist S. (2012) Quantitative analysis of hsp90-client interactions reveals principles of substrate recognition. Cell 150, 987–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sawyers C. (2004) Targeted cancer therapy. Nature 432, 294–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kwak E. L., Bang Y. J., Camidge D. R., Shaw A. T., Solomon B., Maki R. G., Ou S. H., Dezube B. J., Jänne P. A., Costa D. B., Varella-Garcia M., Kim W. H., Lynch T. J., Fidias P., Stubbs H., Engelman J. A., Sequist L. V., Tan W., Gandhi L., Mino-Kenudson M., Wei G. C., Shreeve S. M., Ratain M. J., Settleman J., Christensen J. G., Haber D. A., Wilner K., Salgia R., Shapiro G. I., Clark J. W., Iafrate A. J. (2010) Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1693–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi H., Hugo W., Kong X., Hong A., Koya R. C., Moriceau G., Chodon T., Guo R., Johnson D. B., Dahlman K. B., Kelley M. C., Kefford R. F., Chmielowski B., Glaspy J. A., Sosman J. A., van Baren N., Long G. V., Ribas A., Lo R. S. (2014) Acquired Resistance and Clonal Evolution in Melanoma during BRAF Inhibitor Therapy. Cancer Discov., 4, 80–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wagle N., Emery C., Berger M. F., Davis M. J., Sawyer A., Pochanard P., Kehoe S. M., Johannessen C. M., Macconaill L. E., Hahn W. C., Meyerson M., Garraway L. A. (2011) Dissecting therapeutic resistance to RAF inhibition in melanoma by tumor genomic profiling. J. Clin. Oncol., 29, 3085–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trepel J., Mollapour M., Giaccone G., Neckers L. (2010) Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 537–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taipale M., Jarosz D. F., Lindquist S. (2010) HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 515–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu W., Neckers L. (2007) Targeting the molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90 provides a multifaceted effect on diverse cell signaling pathways of cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 1625–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Modi S., Stopeck A., Linden H., Solit D., Chandarlapaty S., Rosen N., D'Andrea G., Dickler M., Moynahan M. E., Sugarman S., Ma W., Patil S., Norton L., Hannah A. L., Hudis C. (2011) HSP90 Inhibition is effective in breast cancer: a phase II trial of tanespimycin (17-AAG) plus trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer progressing on trastuzumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 5132–5139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Solit D. B., Osman I., Polsky D., Panageas K. S., Daud A., Goydos J. S., Teitcher J., Wolchok J. D., Germino F. J., Krown S. E., Coit D., Rosen N., Chapman P. B. (2008) Phase II trial of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 8302–8307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arteaga C. L. (2011) Why is this effective HSP90 inhibitor not being developed in HER2+ breast cancer? Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 4919–4921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scaltriti M., Dawood S., Cortes J. (2012) Molecular pathways: targeting hsp90–who benefits and who does not. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 4508–4513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leu J. I., Pimkina J., Frank A., Murphy M. E., George D. L. (2009) A small molecule inhibitor of inducible heat shock protein 70. Mol. Cell 36, 15–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murphy M. E. (2013) The HSP70 family and cancer. Carcinogenesis 34, 1181–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Balaburski G. M., Leu J. I., Beeharry N., Hayik S., Andrake M. D., Zhang G., Herlyn M., Villanueva J., Dunbrack R. L., Jr., Yen T., George D. L., Murphy M. E. (2013) A modified HSP70 inhibitor shows broad activity as an anticancer agent. Mol. Cancer Res. 11, 219–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi H., Hong A., Kong X., Koya R. C., Song C., Moriceau G., Hugo W., Yu C. C., Ng C., Chodon T., Scolyer R. A., Kefford R. F., Ribas A., Long G. V., Lo R. S. (2014) A novel AKT1 mutant amplifies an adaptive melanoma response to BRAF inhibition. Cancer Discov., 4, 69–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Duncan J. S., Whittle M. C., Nakamura K., Abell A. N., Midland A. A., Zawistowski J. S., Johnson N. L., Granger D. A., Jordan N. V., Darr D. B., Usary J., Kuan P. F., Smalley D. M., Major B., He X., Hoadley K. A., Zhou B., Sharpless N. E., Perou C. M., Kim W. Y., Gomez S. M., Chen X., Jin J., Frye S. V., Earp H. S., Graves L. M., Johnson G. L. (2012) Dynamic reprogramming of the kinome in response to targeted MEK inhibition in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell 149, 307–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abel E. V., Basile K. J., Kugel C. H., 3rd, Witkiewicz A. K., Le K., Amaravadi R. K., Karakousis G. C., Xu X., Xu W., Schuchter L. M., Lee J. B., Ertel A., Fortina P., Aplin A. E. (2013) Melanoma adapts to RAF/MEK inhibitors through FOXD3-mediated upregulation of ERBB3. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 2155–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tworkoski K., Singhal G., Szpakowski S., Zito C. I., Bacchiocchi A., Muthusamy V., Bosenberg M., Krauthammer M., Halaban R., Stern D. F. (2011) Phosphoproteomic screen identifies potential therapeutic targets in melanoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 9, 801–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sensi M., Catani M., Castellano G., Nicolini G., Alciato F., Tragni G., De Santis G., Bersani I., Avanzi G., Tomassetti A., Canevari S., Anichini A. (2011) Human cutaneous melanomas lacking MITF and melanocyte differentiation antigens express a functional Axl receptor kinase. J. Invest. Dermatol. 131, 2448–2457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Conrad W. H., Swift R. D., Biechele T. L., Kulikauskas R. M., Moon R. T., Chien A. J. (2012) Regulating the response to targeted MEK inhibition in melanoma: enhancing apoptosis in NRAS- and BRAF-mutant melanoma cells with Wnt/β-catenin activation. Cell Cycle 11, 3724–3730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Biechele T. L., Kulikauskas R. M., Toroni R. A., Lucero O. M., Swift R. D., James R. G., Robin N. C., Dawson D. W., Moon R. T., Chien A. J. (2012) Wnt/β-catenin signaling and AXIN1 regulate apoptosis triggered by inhibition of the mutant kinase BRAFV600E in human melanoma. Sci. Signal. 5, ra3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.