While HMG-CoA-reductase inhibitors (statins) have significantly contributed to the reduction in major adverse cardiac events observed in primary and secondary prevention trials, in part, by lowering circulating low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), ischemic cardiovascular disease still remains the number one cause of death in the US, suggesting that additional therapies that address patient “residual risk” are desperately needed.1, 2 Recent epidemiological studies in patients treated with statins suggest a marked association with levels of circulating high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) and future cardiovascular risk independent of LDL-C.3 Indeed, an inverse association has been implicated for HDL-C and future cardiovascular risk from various populations.4 While several prospective studies aimed to increase HDL-C have not demonstrated improved efficacy for major adverse cardiovascular events, intense scientific interest remains at identifying new targets that harness many of the salutary pleiotropic effects of HDL-C such as promoting efflux of cholesterol from the vessel wall, reducing inflammation, or facilitating reverse cholesterol transport.5–7

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, evolutionarily conserved non-coding RNAs that inhibit target genes by binding to the 3’-UTRs of mRNAs to promote mRNA degradation or translational repression. Several miRNAs have been implicated in regulating HDL-C and/or cholesterol metabolism including microRNA-33 (miR-33).8–10 Human miR-33a and miR-33b are located in the introns of the sterol-response-element-binding protein (SREBP) genes SREBP2 and SREBP1, respectively. MiR-33a and miR-33b differ by two nucleotides in their mature form with the same seed sequence. MiR-33a is expressed across different species including rodents, primates, and humans; however, miR-33b is not expressed in rodents. Several groups identified miR-33 as a key regulator in cholesterol metabolism by targeting the adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) in 2010.11–15 Antisense inhibition or genetic deletion of miR-33 resulted in increased ABCA1 expression, HDL-C, and macrophage cholesterol efflux,11, 12, 14, 15 while lentiviral or adenoviral delivery of miR-33 had the opposite effects.12, 15 Emerging studies in non-human primates have also demonstrated increased levels of HDL-C in response to miR-33 inhibition.16, 17 Recent studies, however, examining the role of miR-33 inhibition in the context of atherosclerotic progression have revealed conflicting effects in Ldlr−/− mice.18, 19 Work by Marquart et al.18 showed no effect on atherosclerotic lesion size, composition, or HDL-C, rather, surprisingly, miR-33 inhibition induced a marked increase in circulating triglycerides (TG). In this issue of Circulation Research, work from the same group extend these observations and identified a novel mechanism by which miR-33 controls cholesterol metabolism by regulating the secretion of very low-density lipoprotein-TG (VLDL-TG) (Figure 1).20 Prolonged miR-33 inhibition over 11 weeks increased plasma levels of VLDL-TG in chow-fed C57BL/6 mice due to increased hepatic N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) expression, which they identified as a new direct target of miR-33 utilizing a combination of complementary gain- and loss-of-function approaches. MiR-33 inhibition also increased the secretion of other hepatic-associated proteins including ApoB, ApoA1, and albumin. Knockdown of NSF expression decreased VLDL-TG secretion, which phenocopied the effects of miR-33 overexpression. In contrast, NSF overexpression enhanced VLDL-TG and secretion of other hepatic proteins ApoB, ApoA1, and albumin, and rescued the effect of miR-33. The study demonstrates that the miR-33-NSF axis regulates the overall secretory pathway in both mice and human hepatocytes. Whether similar operative mechanisms exist for miR-33 inhibition in insulin resistant mice, for example, on high-fat diet or in the background of LDLR-deficiency remains unclear. Furthermore, whether the increased plasma VLDL-TG due to miR-33 inhibition in this study exerts any detrimental functional effects on atherosclerotic progression or regression warrants further examination. Nevertheless, the findings by Allen et al.20 add another layer to the complexity of miR-33’s effects in regulating lipoprotein metabolism and shed light to partially explain the discrepancies regarding the role of miR-33 in the progression of atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice as discussed below. Moreover, the study enforces the notion that additional studies may be required for a better understanding of anti-miR-33 therapy prior to translating this promising therapeutic approach from the bench to clinic for ameliorating atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

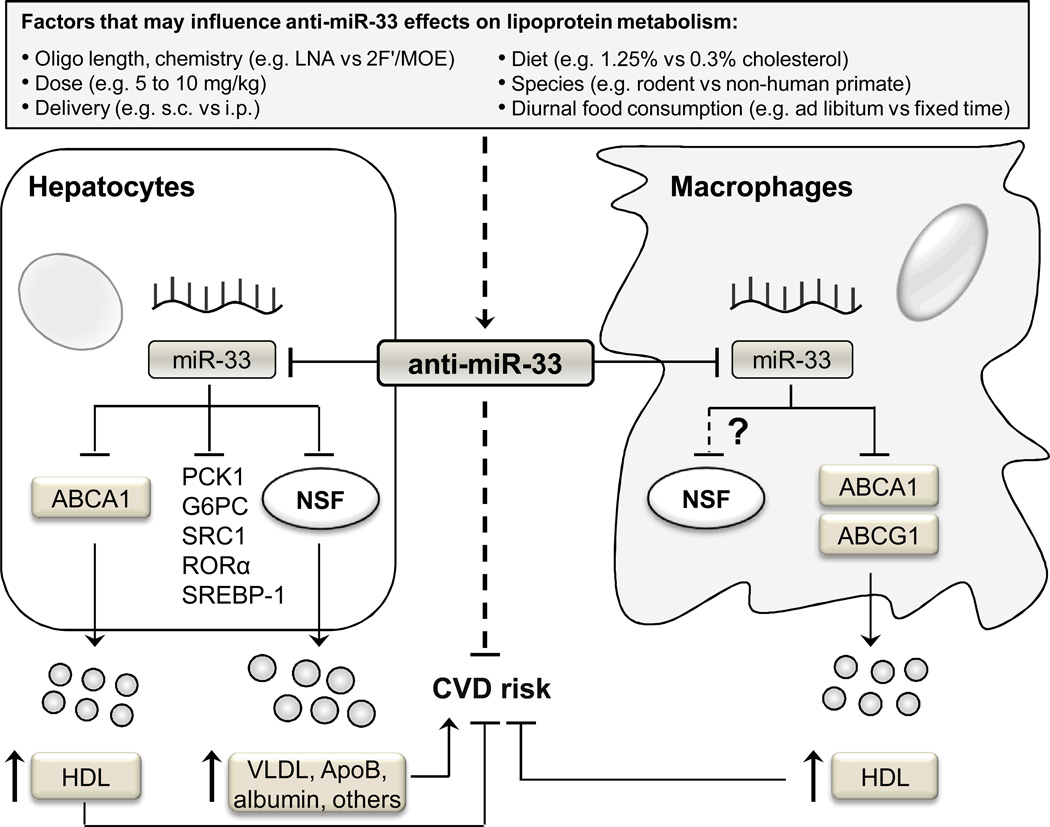

Figure 1. The multifaceted regulation of lipoprotein metabolism by miR-33 and the potential impact on cardiovascular disease.

MiR-33 inhibition may influence HDL, VLDL-TG, and hepatic-secreted proteins to impact cardiovascular disease risk. Inhibition of miR-33 in hepatocytes leads to increased HDL synthesis and hepatic secretion of VLDL-TG and other hepatic proteins due to de-repression of ABCA1 and NSF, respectively. In macrophages, miR-33 targets ABCA1/ABCG1; however, a role for NSF as a direct target of miR-33 remains unexplored in extra-hepatic cell types. Increased VLDL-TG secretion may adversely impact CVD. Inhibition of miR-33 promotes reverse cholesterol transport in macrophages, an effect that may confer protection against CVD. Multiple factors in miR-33 inhibitor studies may account for differences observed across studies on lipoprotein metabolism and/or atherosclerosis: percentage of cholesterol in the diet, length or chemical modification of the anti-miR-33 oligonucleotides, delivery dose/route, length of treatment, and animal strains used.

Accumulating studies among both human subjects and animals reveal a strong association with over-secretion of hepatic apoB100-enriched VLDL particles into the circulation and the development of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, or atherosclerosis.21–25 VLDL-TG particles, secreted by the liver, deliver TGs to other tissues and are subsequently hydrolyzed and converted into intermediate-density lipoprotein and LDL, which are eventually cleared by the liver.26,27 Dysregulation of this process may contribute to excessive accumulation of atherogenic lipoprotein particles in the circulation.28 As such, pharmacologic therapies that reduce VLDL-TG secretion from the liver may offer a complementary approach at limiting hyperlipidemia and, possibly, coronary artery disease (CAD). Indeed, an inhibitor to microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (Mttp), a critical protein for effective hepatic assembly of VLDL, has shown efficacy in lowering LDL in patients with familial homozygous hypercholesterolemia,29, 30 one of the most severe forms of hyperlipidemia (often due to deficiency or absence of the LDL receptor) that can lead to pre-mature CAD, myocardial infarction, and death.31 In the study by Allen et al., while miR-33 inhibition increased secretion of VLDL-TG and ApoB100, it did not alter expression of Mttp or ApoB or regulate their 3’-UTR reporter activities suggesting other potential mechanisms underlying the increased VLDL-TG secretion. Mobilization of ApoB-enriched cargo from the endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi to the cell outer membrane is thought to rely upon an intricate series of proteins, termed soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complexes, that facilitate vesicular membrane fusion and may also bind ApoB100. Using a deductive approach for exploring potential proteins involved in VLDL vesicular trafficking in primary mouse and human hepatocytes, they found that miR-33 overexpression reduced NSF mRNA and protein, whereas expression of others (Napa, Sec22b, Gosr1, Stx5, or Bet1) were not altered. Furthermore, in the presence of miR-33 overexpression, NSF was dynamically recruited into the RNA-induced silencing complex (where miRNAs associate with target mRNA in association with Argonaute-2) and bound to the NSF 3’-UTR, strongly implicating that it is a bona fide miR-33 target in hepatocytes. Interestingly, NSF activity is needed for resolution of the SNARE complexes formed during this vesicular trafficking stage. As such, miR-33 inhibition may, in theory, enhance nascent VLDL trafficking and hepatic VLDL-TG mobilization and secretion by altering a component of this multi-step SNARE-dependent process.32 Because SNARE-regulated vesicular trafficking occurs in a variety of extra-hepatic cell types, including cells involved in innate and adaptive immunity or coagulation, future investigation should consider the tantalizing possibility that miR-33 may alter SNARE-dependent events such as phagocytosis, endocytosis, or the secretion of inflammatory or thrombotic mediators.

Given that miR-33 inhibition has been extensively studied from rodents to non-human primates, the findings from Allen et al.20 also beg the larger question—how do we still reconcile their observations from the other miR-33 inhibition studies,17–19, 33, 34 in which no inductive effects on TG or VLDL-TG were observed? After early studies demonstrated miR-33 inhibition increased HDL-C levels and promoted reverse cholesterol transport, subsequent studies examined its role in regulating circulating lipoproteins and the regression or progression of atherosclerosis in mice.18, 19, 33, 34 Specific influential factors in these miR-33 inhibitor studies include: percentage of cholesterol in the diet, chemical modification of the anti-miR-33 oligonucleotides, delivery dose/route, length of treatment, and animal strains used. To assess the effect of miR-33 inhibition on the regression of atherosclerosis, Rayner et al.34 examined 4-week-old Ldlr−/− mice fed a high-fat diet (0.3% cholesterol) for 14 weeks, followed by chow diet for 4 weeks. Mice were treated with 2’-fluoro/methoxyethyl (2’F/MOE) modified anti-miR-33 (21 nucleotides in length, 10 mg/kg i.p.) during the period of 4-week chow diet. MiR-33 inhibition in these mice increased HDL-C, facilitated reverse cholesterol transport, and reduced plaque size, lipid content, and inflammation.34 However, there was no effect on circulating TGs or VLDL. Three studies subsequently examined miR-33 deficiency on circulating lipoproteins and in the progression of atherosclerosis in mice. First, genetic loss of miR-33 in ApoE−/− mice led to an increase of HDL-C levels and decreased atherosclerotic plaque area throughout the aorta.33 These double knockout mice were fed a western-type diet (0.15% cholesterol) at 6 weeks of age for 16 weeks. Total circulating TGs trended higher in ApoE−/− mice with genetic loss of miR-33; however, it did not reach significance.33 Interestingly, bone marrow transplant studies revealed that chimeric mice with miR-33 myeloid deficiency did not increase HDL-C levels or reduce atherosclerotic plaque size, although lipid accumulation was reduced in atherosclerotic plaques. These data suggest that the protective effect of miR-33 inhibition may not be the result of loss of miR-33-mediated effects in macrophages (e.g. cholesterol efflux), but rather hepatic or extra-hepatic effects. To assess the efficacy of anti-miR-33 inhibitors on the progression of atherosclerosis, Rotllan et al.19 injected 9-week-old Ldlr−/− mice (Jackson Laboratories) subcutaneously with 2’F/MOE phophorothioate anti-miR-33 oligonucleotides (21 nucleotides in length, 10mg/kg), and fed a high-fat diet (0.3% cholesterol) for 12 weeks.19 Anti-miR-33 treatment reduced lesion size and macrophage content, but not collagen content and necrotic areas. Surprisingly, hepatic ABCA1 protein expression was not increased by miR-33 inhibition. In agreement with this observation, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and TG levels were not different among treatments. Nevertheless, HDL from these anti-miR-33-treated mice had, intriguingly, improved functionality evidenced by its ability to promote cellular cholesterol efflux and to protect endothelial cells (ECs) from cytokine-induced activation. In addition, anti-miR-33 increased ABCA1 expression in aortas from mice fed a HFD suggesting that these anti-miRs may penetrate the vessel wall. In chow-fed mice for 4 weeks, anti-miR-33 led to increased plasma HDL, increased hepatic expression of miR-33 targets such as ABCA1 in mice, but plasma TG levels were similar. These data suggest that high-fat diet may blunt effects on circulating HDL-C in response to 2F’/MOE-anti-miR-33 therapy in mice. Finally, Marquart et al.18 examined 10-week-old Ldlr−/− mice injected intraperitoneally with locked nucleic acid (LNA)-anti-miR-33 (15 nucleotides in length, 7 mg/kg), and fed a western diet (1.25% cholesterol) for 12 weeks after two weeks on chow.18 The anti-miR-33 group exhibited a trend for increased body weight gain. HDL-C was not increased by miR-33 inhibition at the end of the western diet feeding, although in the first 2 weeks when the mice were chow-fed HDL-C significantly increased. Mice that received LNA-anti-miR-33 exhibited increased plasma TGs both on chow and after western diet, with similar atherosclerotic lesion size, despite the increase in hepatic expression of miR-33 targets such as ABCA1. Notably, the expression of ABCA1 in aortas was not examined in the study to correlate miR-33 expression, targets, and efficiency of penetration in the vessel wall. Importantly, the level of total cholesterol achieved in this study was significantly higher (~1200 mg/dl on 1.25% cholesterol diet) compared to the study by Rotllan (~900 mg/dl on 0.3% cholesterol diet). In theory, rapid induction of high cholesterol could reduce miR-33 expression to a level beyond the inhibitory effect of LNA-anti-miR-33 in the liver or arterial wall.

Several reasonable explanations may, therefore, underlie why miR-33 depletion has different effects on circulating lipoproteins, and in particular, in the progression of atherosclerosis (Figure 1).18–20, 35 Collectively, diet (1.25% vs 0.3% cholesterol), oligonucleotide length (23 vs 16 nt) and chemistries (LNA vs 2’F/MOE), delivery route (i.p. vs s.c.), and anti-miR dose (7 mg/kg vs 10 mg/kg) may have contributed to the discrepancies for the effects of miR-33 inhibition on circulating HDL, VLDL, TGs, and atherosclerosis. In earlier studies when miR-33 was acutely depleted in mice, no changes of VLDL and TGs levels were reported.11, 15, 17 Different target profiles may be exposed in response to LNA-anti-miR-33 and 2’F/MOE anti-miR-33 treatment, an effect also influenced by acute and prolonged depletion of miR-33. NSF expression may also be differentially regulated upon miR-33 knockdown in different studies. Genetic depletion of miR-33 did not cause an increase of plasma VLDL and TGs in mice,14 which may reflect the activation of compensatory mechanisms or de-repression of factors that counter the increase of NSF expression in the context of complete absence of miR-33.

In addition to its role in cholesterol metabolism, miR-33 also regulates fatty acid and glucose metabolism.13, 36, 37 MiR-33 inhibits fatty acid oxidation and degradation,13, 36 inhibits gluconeogenesis and glycolysis,37 and regulates insulin signaling.36 Interestingly, the passenger strand of miR-33 (miR-33*) shares a similar target gene network as the guide strand in different cell types, suggesting both arms of the miR-33/miR-33* duplex regulate lipid metabolism.38 Surprisingly, genetic deletion of miR-33 aggravated high-fat diet-induced obesity and liver steatosis by targeting the SREBP-1 pathway in mice.39 While there were no changes in circulating TG in WT and miR-33−/− mice, the high-fat diet groups actually had lower circulating TG than the chow-fed groups making interpretation unclear.

Whether similar mechanisms exist for the miR-33-NSF axis regulating VLDL secretion in human subjects remains unknown. However, two studies performed in non-human primates – African green monkeys – demonstrated no such effects on VLDL-TG. Systemic delivery of 2’F/MOE anti-miR-33 oligonucleotide (21 nucleotides in length, 5 mg/kg s.c. twice weekly for two weeks, then weekly for 10 weeks) in African green monkeys increased hepatic expression of miR-33 target genes including ABCA1, and increased plasma HDL-C levels (~50%) over 12 weeks.16 Monkeys were fed a normal chow diet for 4 weeks, then switched to a high carbohydrate, moderate cholesterol diet for 8 weeks. HDL from anti-miR-33 treated monkeys maintained anti-inflammatory properties in ECs, and had similar capacity for cholesterol efflux in macrophages. MiR-33 inhibition surprisingly reduced the plasma levels of VLDL-TG ascribed, in part, to decreased gene expression involved in fatty acid synthesis (e.g. Srebp1 by de-repression of Prkaa1) and increased those involved in fatty acid oxidation (e.g. Hadhb, Cpt1a, and Crot). In a more recent study using African green monkeys, long-term treatment with the 8-mer LNA-anti-miR-33a/b increased HDL (up to 25% on high-fat diet; up to 39% on high carb-diet) and hepatic ABCA1 expression without evidence of off-target effects or toxicity.17 No change in TG levels was detected in response to the 8-mer LNA anti-miR-33a/b treatment. Thus, how do we reconcile why miR-33 inhibition in monkeys had no effect or even decreased levels of plasma VLDL-TG? Potential explanations also highlighted in the discussion by Allen et al.20 include: 1) the clearance of VLDL-TG from circulation is very efficient in African green monkeys, an effect leading to significantly lower baseline circulating VLDL-TG levels (by ~15–30%) compared to VLDL-TG levels in humans.40, 41 Due to this high turnover, hepatic VLDL-TG secretion may be difficult to accurately monitor by a static measurement of plasma TG concentration;42 2) both non-human primate studies did not have important additional control groups; the study by Rayner et al.16 lacked a vehicle control group, whereas the study by Rottiers et al.17 lacked an oligonucleotide control group (but had a vehicle control group). Thus, data interpretation is unclear regarding whether control oligonucleotides raised VLDL-TG in the former, and whether the lack of control oligonucleotides minimized any VLDL-TG effects in the latter; and 3) the study by Rottiers et al.17 reported no difference in TG levels, but TG lipoprotein distribution was not shown. In addition, VLDL and TGs levels measured in circulation in non-human primate studies may need to be carefully interpreted in the absence of blocking the clearance pathway in an analogous manner in mice. Finally, mice, but not monkeys, consumed food ad libitum in the above studies,18, 20 which might need to be taken into consideration for effects of diurnal feeding patterns on lipoprotein metabolism.

The study by Allen et al.20 also raises important issues not only for miR-33 in particular, but also for the field of miRNA therapeutics in general. Relevant points to appreciate include: 1) differences of miRNA expression across species (e.g. miR-33a and miR-33b in humans and primates; only one miR-33 in rodents) may result in differential miRNA regulation and/or target gene expression; 2) differences may exist in bioavailability, potency, penetration efficiency, and pharmacokinetic properties of 2’F/MOE- and LNA-anti-miR-33 in relevant tissues and cell types (e.g. hepatic and extra-hepatic tissues including the vessel wall (ECs and smooth muscle cells), peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and other insulin-responsive depots (e.g. visceral fat and skeletal muscle); 3) diurnal fluctuations of blood lipid, insulin, and glucose levels across rodents, monkeys, and humans can be vastly different; 4) how anti-miR-33 treatment regulates functionality of lipoproteins including HDL and VLDL-TG (e.g. HDL may transfer miRNAs to ECs to exert anti-inflammatory properties43); and 5) whether miR-33, ABCA1, and NSF are dynamically regulated in patients with cardiovascular or metabolic disease.

The role miR-33 in cholesterol efflux, and fatty acid and glucose metabolism, makes it an attractive therapeutic target for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. The study by Allen et al.,20 however, provides scientific pause to further investigate miR-33’s potential effects on VLDL-TG secretion, other hepatic-secreted proteins, and NSF-mediated effects in relevant extra-hepatic cells types that may impact health and disease as this therapy inches towards the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (HL115141 and HL117994) to M.W.F.

Glossary

- ABCA1

indicates the ATP binding cassette transporter A1

- ABCG1

the ATP binding cassette transporter G1

- NSF

N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor

- PCK1

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- G6PC

glucose-6-phosphatase

- SRC1

steroid receptor coactivator 1

- RORα

retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-related orphan receptor alpha

- SREBP-1

the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- VLDL

very low-density lipoprotein

- TG

triglycerides

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- LNA

locked nucleic acid

- 2’F/MOE

fluoro/methoxyethyl

- ApoB

apolipoprotein B

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, Bhala N, Peto R, Barnes EH, Keech A, Simes J, Collins R. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of ldl cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, Maroni J, Szarek M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Bittner V, Fruchart JC. Hdl cholesterol, very low levels of ldl cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357:1301–1310. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, Neaton JD, Castelli WP, Knoke JD, Jacobs DR, Jr, Bangdiwala S, Tyroler HA. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective american studies. Circulation. 1989;79:8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rye KA, Barter PJ. Regulation of high-density lipoprotein metabolism. Circulation research. 2014;114:143–156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Capelleveen JC, Brewer HB, Kastelein JJ, Hovingh GK. Novel therapies focused on the high-density lipoprotein particle. Circulation research. 2014;114:193–204. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feig JE, Hewing B, Smith JD, Hazen SL, Fisher EA. High-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis regression: Evidence from preclinical and clinical studies. Circulation research. 2014;114:205–213. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouimet M, Moore KJ. A big role for small rnas in hdl homeostasis. Journal of lipid research. 2013;54:1161–1167. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotllan N, Fernandez-Hernando C. Microrna regulation of cholesterol metabolism. Cholesterol. 2012;2012:847–849. doi: 10.1155/2012/847849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rayner KJ, Moore KJ. Microrna control of high-density lipoprotein metabolism and function. Circulation research. 2014;114:183–192. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Kristo F, Li Y, Shioda T, Cohen DE, Gerszten RE, Naar AM. Microrna-33 and the srebp host genes cooperate to control cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 2010;328:1566–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.1189123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rayner KJ, Suarez Y, Davalos A, Parathath S, Fitzgerald ML, Tamehiro N, Fisher EA, Moore KJ, Fernandez-Hernando C. Mir-33 contributes to the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 2010;328:1570–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1189862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerin I, Clerbaux LA, Haumont O, Lanthier N, Das AK, Burant CF, Leclercq IA, MacDougald OA, Bommer GT. Expression of mir-33 from an srebp2 intron inhibits cholesterol export and fatty acid oxidation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:33652–33661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.152090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horie T, Ono K, Horiguchi M, Nishi H, Nakamura T, Nagao K, Kinoshita M, Kuwabara Y, Marusawa H, Iwanaga Y, Hasegawa K, Yokode M, Kimura T, Kita T. Microrna-33 encoded by an intron of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (srebp2) regulates hdl in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:17321–17326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008499107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marquart TJ, Allen RM, Ory DS, Baldan A. Mir-33 links srebp-2 induction to repression of sterol transporters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12228–12232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005191107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rayner KJ, Esau CC, Hussain FN, McDaniel AL, Marshall SM, van Gils JM, Ray TD, Sheedy FJ, Goedeke L, Liu X, Khatsenko OG, Kaimal V, Lees CJ, Fernandez-Hernando C, Fisher EA, Temel RE, Moore KJ. Inhibition of mir-33a/b in non-human primates raises plasma hdl and lowers vldl triglycerides. Nature. 2011;478:404–407. doi: 10.1038/nature10486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rottiers V, Obad S, Petri A, McGarrah R, Lindholm MW, Black JC, Sinha S, Goody RJ, Lawrence MS, deLemos AS, Hansen HF, Whittaker S, Henry S, Brookes R, Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Chung RT, Whetstine JR, Gerszten RE, Kauppinen S, Naar AM. Pharmacological inhibition of a microrna family in nonhuman primates by a seed-targeting 8-mer antimir. Science translational medicine. 2013;5:212ra162. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marquart TJ, Wu J, Lusis AJ, Baldan A. Anti-mir-33 therapy does not alter the progression of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:455–458. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotllan N, Ramirez CM, Aryal B, Esau CC, Fernandez-Hernando C. Therapeutic silencing of microrna-33 inhibits the progression of atherosclerosis in ldlr−/− mice--brief report. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:1973–1977. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen RM, Marquart TJ, Jesse JJ, Baldan A. Control of very-low density lipoprotein secretion by n-ethylmaleimide--sensitive factor and mir-33. Circulation research. 2014;115:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hokanson JE, Austin MA. Plasma triglyceride level is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level: A meta-analysis of population-based prospective studies. Journal of cardiovascular risk. 1996;3:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.VanderLaan PA, Reardon CA, Thisted RA, Getz GS. Vldl best predicts aortic root atherosclerosis in ldl receptor deficient mice. Journal of lipid research. 2009;50:376–385. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800284-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:299–308. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adiels M, Boren J, Caslake MJ, Stewart P, Soro A, Westerbacka J, Wennberg B, Olofsson SO, Packard C, Taskinen MR. Overproduction of vldl1 driven by hyperglycemia is a dominant feature of diabetic dyslipidemia. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2005;25:1697–1703. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000172689.53992.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adiels M, Olofsson SO, Taskinen MR, Boren J. Overproduction of very low-density lipoproteins is the hallmark of the dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28:1225–1236. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. doi: 10.1126/science.3513311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginsberg HN, Fisher EA. The ever-expanding role of degradation in the regulation of apolipoprotein b metabolism. Journal of lipid research. 2009;50(Suppl):S162–S166. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800090-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bamba V, Rader DJ. Obesity and atherogenic dyslipidemia. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2181–2190. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuchel M, Bloedon LT, Szapary PO, Kolansky DM, Wolfe ML, Sarkis A, Millar JS, Ikewaki K, Siegelman ES, Gregg RE, Rader DJ. Inhibition of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in familial hypercholesterolemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356:148–156. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuchel M, Meagher EA, du Toit Theron H, Blom DJ, Marais AD, Hegele RA, Averna MR, Sirtori CR, Shah PK, Gaudet D, Stefanutti C, Vigna GB, Du Plessis AM, Propert KJ, Sasiela WJ, Bloedon LT, Rader DJ. Efficacy and safety of a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitor in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: A single-arm, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2013;381:40–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin MA, Hutter CM, Zimmern RL, Humphries SE. Familial hypercholesterolemia and coronary heart disease: A huge association review. American journal of epidemiology. 2004;160:421–429. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stow JL, Manderson AP, Murray RZ. Snareing immunity: The role of snares in the immune system. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2006;6:919–929. doi: 10.1038/nri1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horie T, Baba O, Kuwabara Y, Chujo Y, Watanabe S, Kinoshita M, Horiguchi M, Nakamura T, Chonabayashi K, Hishizawa M, Hasegawa K, Kume N, Yokode M, Kita T, Kimura T, Ono K. Microrna-33 deficiency reduces the progression of atherosclerotic plaque in apoe−/− mice. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2012;1:e003376. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.003376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rayner KJ, Sheedy FJ, Esau CC, Hussain FN, Temel RE, Parathath S, van Gils JM, Rayner AJ, Chang AN, Suarez Y, Fernandez-Hernando C, Fisher EA, Moore KJ. Antagonism of mir-33 in mice promotes reverse cholesterol transport and regression of atherosclerosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:2921–2931. doi: 10.1172/JCI57275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naar AM. Anti-atherosclerosis or no anti-atherosclerosis: That is the mir-33 question. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:447–448. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.301021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davalos A, Goedeke L, Smibert P, Ramirez CM, Warrier NP, Andreo U, Cirera-Salinas D, Rayner K, Suresh U, Pastor-Pareja JC, Esplugues E, Fisher EA, Penalva LO, Moore KJ, Suarez Y, Lai EC, Fernandez-Hernando C. Mir-33a/b contribute to the regulation of fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:9232–9237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102281108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramirez CM, Goedeke L, Rotllan N, Yoon JH, Cirera-Salinas D, Mattison JA, Suarez Y, de Cabo R, Gorospe M, Fernandez-Hernando C. Microrna 33 regulates glucose metabolism. Molecular and cellular biology. 2013;33:2891–2902. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00016-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goedeke L, Vales-Lara FM, Fenstermaker M, Cirera-Salinas D, Chamorro-Jorganes A, Ramirez CM, Mattison JA, de Cabo R, Suarez Y, Fernandez-Hernando C. A regulatory role for microrna 33* in controlling lipid metabolism gene expression. Molecular and cellular biology. 2013;33:2339–2352. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01714-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horie T, Nishino T, Baba O, Kuwabara Y, Nakao T, Nishiga M, Usami S, Izuhara M, Sowa N, Yahagi N, Shimano H, Matsumura S, Inoue K, Marusawa H, Nakamura T, Hasegawa K, Kume N, Yokode M, Kita T, Kimura T, Ono K. Microrna-33 regulates sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 expression in mice. Nature communications. 2013;4:2883. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin W, Carballo-Jane E, McLaren DG, Mendoza VH, Gagen K, Geoghagen NS, McNamara LA, Gorski JN, Eiermann GJ, Petrov A, Wolff M, Tong X, Wilsie LC, Akiyama TE, Chen J, Thankappan A, Xue J, Ping X, Andrews G, Wickham LA, Gai CL, Trinh T, Kulick AA, Donnelly MJ, Voronin GO, Rosa R, Cumiskey AM, Bekkari K, Mitnaul LJ, Puig O, Chen F, Raubertas R, Wong PH, Hansen BC, Koblan KS, Roddy TP, Hubbard BK, Strack AM. Plasma lipid profiling across species for the identification of optimal animal models of human dyslipidemia. Journal of lipid research. 2012;53:51–65. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M019927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marzetta CA, Johnson FL, Zech LA, Foster DM, Rudel LL. Metabolic behavior of hepatic vldl and plasma ldl apob-100 in african green monkeys. Journal of lipid research. 1989;30:357–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parks JS, Johnson FL, Wilson MD, Rudel LL. Effect of fish oil diet on hepatic lipid metabolism in nonhuman primates: Lowering of secretion of hepatic triglyceride but not apob. Journal of lipid research. 1990;31:455–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabet F, Vickers KC, Cuesta Torres LF, Wiese CB, Shoucri BM, Lambert G, Catherinet C, Prado-Lourenco L, Levin MG, Thacker S, Sethupathy P, Barter PJ, Remaley AT, Rye KA. Hdl-transferred microrna-223 regulates icam-1 expression in endothelial cells. Nature communications. 2014;5:3292. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.