Abstract

Purpose

Urinary incontinence (UI) following prostate radiotherapy is a rare toxicity that adversely affects a patient’s quality of life. This study sought to evaluate the incidence of UI following stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for prostate cancer.

Methods

Between February, 2008 and October, 2010, 204 men with clinically localized prostate cancer were treated definitively with SBRT at Georgetown University Hospital. Patients were treated to 35–36.25 Gray (Gy) in 5 fractions delivered with the CyberKnife (Accuray). UI was assessed via the Expanded Prostate Index Composite (EPIC)-26.

Results

Baseline UI was common with 4.4%, 1.0% and 3.4% of patients reporting leaking > 1 time per day, frequent dribbling and pad usage, respectively. Three year post treatment, 5.7%, 6.4% and 10.8% of patients reported UI based on leaking > 1 time per day, frequent dribbling and pad usage, respectively. Average EPIC UI summary scores showed an acute transient decline at one month post-SBRT then a second a gradual decline over the next three years. The proportion of men feeling that their UI was a moderate to big problem increased from 1% at baseline to 6.4% at three years post-SBRT.

Conclusions

Prostate SBRT was well tolerated with UI rates comparable to conventionally fractionated radiotherapy and brachytherapy. More than 90% of men who were pad-free prior to treatment remained pad-free three years following treatment. Less than 10% of men felt post-treatment UI was a moderate to big problem at any time point following treatment. Longer term follow-up is needed to confirm late effects.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, SBRT, Urinary incontinence, Expanded prostate index composite, EPIC, CyberKnife, Quality of life

Background

Involuntary leakage of urine is a common problem of aging. Urinary incontinence (UI) varies in frequency and severity, making it clinically challenging to define. In men greater than sixty five years old, the prevalence of UI may be as high is 31% [1]. UI is caused by an overactive bladder (urge incontinence) and/or poor urethral sphincter function (stress incontinence) [2]. Aging, comorbidities, obesity, benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostate cancer and its treatments may increase the risk of UI [3]. Urinary continence recovery following radical prostatectomy is variable with 5-30% of patients still requiring pads one year after surgery [4,5]. The incidence of UI after external beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy varies considerably with a reported range of 10% to 30% [6-9]. The incidence of UI is dependent on the definition utilized [10] and on the manner of data collection (i.e. patient or physician reported) [11]. Post-treatment UI develops months to years after radiation therapy without recovery [8,9] and may adversely affect a patient’s sexual function and general quality of life [12]. Bother from UI varies based on its severity [13,14]. UI is commonly refractory to treatment [15] and the daily usage of pads is a burden for patients and caregivers [16].

Clinical data suggest that hypofractionated radiation therapy may be radiobiologically favorable to smaller fraction sizes in prostate cancer radiotherapy [17]. The α/β for prostate cancer may be as low as 1.5 Gy (Gray) [17]. If the α/β for prostate cancer is less than 3 Gy, which is generally the value accepted for late urinary complications, the linear-quadratic model predicts that delivering large radiation fraction sizes will result in improved local control with a similar rate of urinary complications. Early data from trials of limited hypofractionation (fraction sizes from 2.5 to 3.5 Gy) revealed that such regimens are effective without undue urinary toxicity [18].

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) uses even larger daily fractions of radiation (7–9 Gy) to take further advantage of this postulated radiobiological advantage. Emerging clinical data suggest that this approach may provide similar clinical outcomes as other radiation modalities with high rates of biochemical control and low rates of grade 3 and higher toxicities [19-25]. Based on patient preference for a shorter treatment course, SBRT utilization is likely to increase as long as toxicity is acceptable. Here, we present our institutional patient-reported urinary incontinence rates following SBRT for clinically localized prostate cancer.

Methods

Patient selection

Patients eligible for study inclusion had histologically-confirmed prostate cancer treated per our institutional protocol. Prospectively collected quality of life (QoL) data for all patients included in our institutional database were retrospectively analyzed with Georgetown University Internal Review Board (IRB) approval.

SBRT treatment planning and delivery

SBRT treatment planning and delivery were conducted as previously described [22,26]. Four gold markers were placed into the prostate. Several days after marker placement, patients underwent magnetic resonance (MR) imaging followed shortly thereafter by a computed tomography (CT) scan. Fused CT and MR images were used for treatment planning. The clinical target volume (CTV) included the prostate and the proximal seminal vesicles. The planning target volume (PTV) equaled the CTV expanded 3 mm posteriorly and 5 mm in all other dimensions. The prescription dose was 35–36.25 Gy to the PTV delivered in five fractions of 7–7.25 Gy corresponding to a tumor equivalent dose in 2-Gy fractions (EQD2) of approximately 85–90 Gy assuming an alpha/ beta ratio of 1.5. The bladder and membranous urethra were contoured and evaluated with dose-volume histogram analysis during treatment planning using Multiplan (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) inverse treatment planning as previously defined. The dose-volume histogram (DVH) goals were for < 50% membranous urethra and < 5 cc of the bladder receiving 37 Gy. To minimize the risk of local recurrence, the dose to the prostatic urethra was not constrained [27]. Target position was verified multiple times during each treatment using paired, orthogonal x-ray images [28].

Follow-up and statistical analysis

Patients completed the Short Form-12 Health Survey (SF-12) [29], the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA) [30] and Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC)-26 [31] before treatment and during routine follow-up visits one month after the completion of SBRT, every 3 months for the first year and then every 6 months for the second and third years. UI was assessed via the urinary incontinence domain of the Expanded Prostate Index Composite (EPIC)-26 [31]. The EPIC-26 UI domain includes three questions related to function (Questions 1–3 of the EPIC-26) and one question related to bother (Question 4 of the EPIC-26). The functions assessed included UI frequency, urinary control and pad usage [32]. For each EPIC question, the responses were grouped into three to four clinically relevant categories. UI rates were defined using three separate commonly employed definitions: leaking > one time per day, frequent dribbling and daily pad usage [8]. To statistically compare changes between time points, the levels of responses were assigned a score and the significance of the mean changes in the scores was assessed by paired t test.

EPIC summary scores for the UI domain range from 0–100 with lower values representing worsening UI. The minimally important difference (MID) in EPIC score was defined as a change of one-half standard deviation (SD) from the baseline [33]. The EPIC UI domain summary scores were stratified to three levels of severity as previously described [34]: severe (0–49), moderate (50–69) and mild (70–100). Multiple logistic regression with backward elimination was used in the multivariate analysis to search for possible predicting factors for UI. The endpoint for this analysis was the EPIC UI subdomain score at 3 years post-SBRT. Baseline characteristics including age, prostate volume, α1A inhibitor usage, and AUA scores were included as variables in the logistic regression model.

Results

From February 2008 to October 2010, 204 prostate cancer patients were treated per our institutional SBRT monotherapy protocol (Table 1). The median follow-up was 3.9 years. They were ethnically diverse with 45.6% being of non-Caucasian ancestry and a median age of 69 years (range, 48–90 years). Obesity and comorbidities were common. 50% of patients had moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms prior to treatment (baseline AUA ≥ 8) with a median baseline AUA of 7.5 (Table 2). The median prostate volume was 39 (11.6-138.7) cc and 7.8% had prior procedures for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). 27.9% of patients utilized alpha-antagonists prior to SBRT. By D’Amico classification, 81 patients were low-, 106 intermediate-, and 17 high-risk. Twenty nine patients (14.2%) also received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with median duration of 3 months (range, 3–24 mon). 88.2% of the patients were treated with 36.25 Gy in five 7.25 Gy fractions.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics and treatment

| Patients (N=204) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Age (y/o) |

Median 69 (48~90) |

|

| |

Age ≤ 60 |

12.7% |

| |

60 < Age ≤ 70 |

46.6% |

| |

Age > 70 |

40.7% |

|

Race |

White |

54.4% |

| |

Black |

38.7% |

| |

Other |

7.8% |

|

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

CCI=0 |

65.2% |

| |

CCI=1 |

21.1% |

| |

CCI≥2 |

13.7% |

|

Body Mass Index (BMI) |

Median 27.60 (15.02-44.96) |

|

| |

BMI ≥ 30 |

30.5% |

|

Partner Status |

Married or Partnered |

76.0% |

| |

Not Partnered |

24.0% |

|

Employment Status |

Working |

48.0% |

| |

Not Working |

52.0% |

|

Median Prostate Volume (cc) |

Median 39 (11.6-138.7) cc |

|

|

Procedure for BPH |

|

7.8% |

|

α

1A

inhibitor usage |

|

27.9% |

|

Risk Groups (D’Amico’s) |

Low |

39.7% |

| |

Intermediate |

52.0% |

| |

High |

8.3% |

|

ADT |

|

14.2% |

|

SBRT Dose |

36.25 Gy |

88.2% |

| 35 Gy | 11.8% |

Table 2.

Pre-treatment Quality of Life (QOL) scores

| |

(n=204) |

|

|

|

Baseline AUA Score |

% Patients |

|

|

|

0-7 (mild) |

50.0% |

|

|

|

8-19 (moderate) |

43.6% |

|

|

|

≥ 20 (Severe) |

6.4% |

|

|

|

Baseline SF-12 Score |

Mean (Range) |

SD |

|

|

PCS (Physical Health Score) |

49.9 (15.6-64.4) |

8.76 |

|

|

MCS (Mental Health Score) |

56.6 (27.2-69.5) |

6.71 |

|

|

Baseline EPIC-26 Incontinence Score |

Mean (Range) |

SD |

MID |

|

Bother |

92.5 (25-100) |

14.79 |

7.4 |

| Summary | 92.3 (18.8-100) | 13.99 | 7.0 |

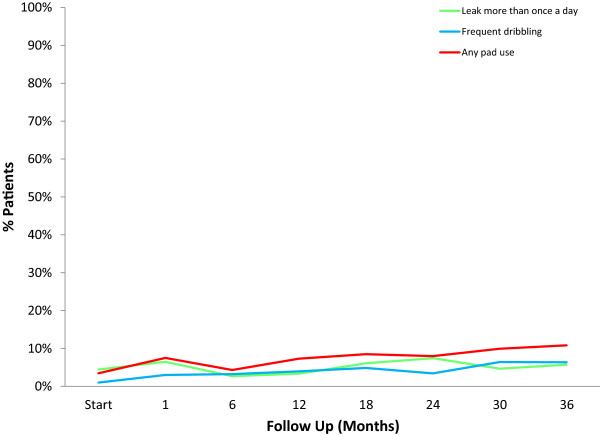

Baseline UI was common in our patients. Prior to treatment, 4.4% of the patients reporting leaking once per day or more and 1% reported frequent dribbling or no control at all (Table 3, Figure 1). Unexpectedly, 3.5% of patients reported using one or more pads per a day prior to SBRT (Table 3, Figure 1). At three year post treatment, 5.7%, 6.4% and 10.8% of patients reported incontinence based on the definitions of leaking > one time per day, frequent dribbling and pad usage, respectively (Table 3, Figure 1). However, only 1.9% reported no control of urination and only 4.5% reported using more than one pad per a day (Table 3). The increase in pad usage was unlikely solely due to aging, as the mean age of pad-using patients at 36 months (73.8 y/o) was not statistically different from non-pad using patients (71.3 y/o) (p = 0.106).

Table 3.

Urinary Incontinence following SBRT for prostate cancer: patient-reported responses to EPIC-26 questions 1 (frequency of leakage), 2 (urinary control), 3 (pad usage), 4a (dripping or leaking urine) and UI domain scores

| |

Start |

1 M |

6 M |

12 M |

18 M |

24 M |

30 M |

36 M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N= | 204 | 200 | 186 | 178 | 165 | 175 | 171 | 157 |

|

Frequency of leakage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Never leak |

79.3% |

69.5% |

69.9% |

69.1% |

69.7% |

68.0% |

65.5% |

64.3% |

|

Leak ≤ 1 time/day |

16.3% |

24.0% |

27.4% |

27.5% |

24.2% |

24.6% |

29.8% |

29.9% |

|

Leak >1 time/day |

4.4% |

6.5% |

2.7% |

3.4% |

6.1% |

7.4% |

4.7% |

5.7% |

|

Urinary Control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total Control |

72.9% |

61.8% |

61.8% |

54.8% |

57.6% |

65.1% |

59.1% |

57.3% |

|

Occasional dribbling |

26.1% |

35.2% |

34.9% |

41.2% |

37.0% |

31.4% |

34.5% |

36.3% |

|

Frequent dribbling |

0.0% |

2.0% |

1.6% |

1.7% |

3.0% |

3.4% |

5.8% |

4.5% |

|

No control |

1.0% |

1.0% |

1.6% |

2.3% |

1.8% |

0.0% |

0.6% |

1.9% |

|

Pad Usage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No pads |

96.6% |

92.5% |

95.7% |

92.7% |

91.5% |

92.0% |

90.1% |

89.2% |

|

1 pad/day |

3.0% |

5.5% |

3.2% |

5.1% |

6.1% |

5.1% |

6.4% |

6.3% |

|

≥ 2 pads/day |

0.5% |

2.0% |

1.1% |

2.2% |

2.4% |

2.9% |

3.5% |

4.5% |

|

Bother-dripping/leaking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No problem |

75.9% |

62.9% |

68.3% |

61.8% |

64.2% |

60.6% |

60.8% |

58.0% |

|

Small problem |

23.2% |

34.5% |

30.1% |

34.8% |

29.7% |

33.7% |

34.5% |

35.7% |

|

Mod-Big problem |

1.0% |

2.5% |

1.6% |

3.4% |

6.1% |

5.7% |

4.7% |

6.4% |

|

UI Domain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mild (70-100) |

90.1% |

85.5% |

86.6% |

84.8% |

81.8% |

85.1% |

83.6% |

84.7% |

|

Moderate (50-69) |

7.4% |

11.0% |

11.8% |

12.4% |

14.5% |

9.1% |

11.1% |

8.3% |

| Severe (0-49) | 2.5% | 3.5% | 1.6% | 2.8% | 3.6% | 5.7% | 5.3% | 7.0% |

Figure 1.

Differences in rates of urinary incontinence based on definition. Percentage of patients with leakage > 1 time a day, frequent dribbling or daily pad usage.

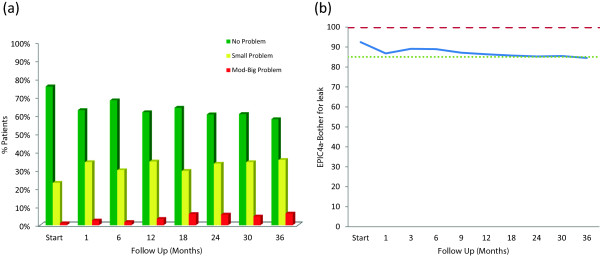

Treatment-related bother may be more important to an individual patient than treatment-related dysfunction. At baseline, 24.2% of our cohort reported some level of bother due to urinary dripping or leaking with 1.0% of the patients feeling it was a moderate to big problem (Table 3, Figure 2a). The baseline UI bother score is shown in Table 2 and mean changes in EPIC UI bother scores from baseline to 3 years of follow-up are shown in Table 4. The mean EPIC UI bother score was 92.5 at baseline (Table 2). UI bother increased following treatment with the mean score decreasing to 86.8 at 1 month post-treatment (mean change, −5.69) (p < 0.0001) (Table 4, Figure 2b). However, only 2.5% of patients felt that that was a moderate to big problem at 1 month following treatment (Table 3, Figure 2a). Although UI bother improved quickly, a second late worsening in UI bother was observed with the mean UI bother score decreasing to 84.55 at 36 months (mean change from baseline, −7.93) (p < 0.0001) (Table 4, Figure 2b). Only the decline at 36 months met the threshold for clinically significant change (MID =7.4). The proportion of men feeling that their UI was a moderate to big problem increased to 6.4% at three years post-SBRT (Table 3, Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Bother with dripping or leaking at baseline and following SBRT for prostate cancer- Question 4 of the EPIC-26. (a) Patients were stratified to three groups: no problem, very small-small problem and moderate-big problem. The percentage of patients in each group at each time point is depicted in the bar chart. (b) Average EPIC bother with dripping or leaking scores at baseline and following SBRT for prostate cancer. Thresholds for clinically significant changes in scores (½ standard deviation above and below the baseline) are marked with dashed lines. EPIC scores range from 0–100 with higher values representing a more favorable health-related QOL.

Table 4.

Changes in urinary incontinence bother and urinary incontinence summary scores following SBRT for prostate cancer

| |

1 Month Post-Treatment |

3 Month Post-Treatment |

12 Month Post-Treatment |

24 Month Post-Treatment |

36 Month Post-Treatment |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change from Baseline | SD | P | Change from Baseline | SD | P | Change from Baseline | SD | P | Change from Baseline | SD | P | Change from Baseline | SD | P | |

|

UI Bother |

-5.69 |

19.65 |

< 0.0001 |

-3.35 |

18.74 |

0.007 |

-6.11 |

20.08 |

< 0.0001 |

-7.2 |

22.93 |

< 0.0001 |

-7.93 |

22.56 |

< 0.0001 |

| UI Summary | -4.09 | 16.74 | < 0.0001 | -1.84 | 14.99 | 0.065 | -4.77 | 16.35 | < 0.0001 | -4.69 | 18.47 | < 0.001 | -6.46 | 19.45 | < 0.0001 |

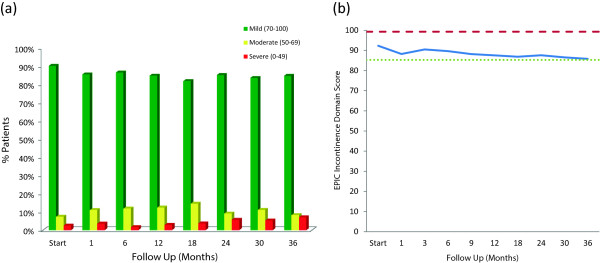

There is no universally-accepted definition for UI and commonly employed definitions based on responses to individual questions do not fully assess the clinical impact of the problem (i.e., symptom, dysfunction and bother). Domain summary scores more comprehensively assess the clinical impact of UI on the patient [31]. The baseline EPIC UI summary score is shown in Table 2 and mean changes in EPIC UI summary scores from baseline to 3 years of follow-up are shown in Table 4. At baseline, 10% of our cohort had moderate to severe UI (Table 3, Figure 3a). The mean EPIC UI summary score was 92.3 at baseline (Table 2). The EPIC UI summary score declined acutely at 1 month post-SBRT (mean change, −4.09) (Table 5, Figure 3b). However, only 14.5% of patients had moderate to severe UI (Table 3, Figure 3a). The EPIC UI summary score returned to near baseline by three months post-SBRT (mean change from baseline, −1.84) (Table 4, Figure 3b). This acute decline was statistically (p < 0.0001) but not clinically significant (MID = 7). Average EPIC UI summary scores showed a second late protracted decline over the next three years (Table 4, Figure 3b). At three years post-treatment, the mean summary score decreased from a baseline of 92.31 to 85.85 (mean change from baseline at 36 months, −6.46) (Table 4). This change was statistically (p < 0.0001) but of borderline clinical significance (MID = 7). The proportion of men with moderate to severe UI increased to 15.3% at three years post-SBRT (Table 3, Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

EPIC Urinary Incontinence Domain. (a) Patients were stratified to three groups: severe (0–49), moderate (50–69) and mild (70–100). (b) Average EPIC urinary incontinence domain scores at baseline and following SBRT for prostate cancer. Thresholds for clinically significant changes in scores (½ standard deviation above and below the baseline) are marked with dashed lines. EPIC scores range from 0–100 with higher values representing a more favorable health-related QOL.

Table 5.

Impact of baseline characteristics on EPIC-UI score three years post-SBRT

| |

Model with age and prostate volume |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | t Value | Pr > |t| | |

|

Intercept |

111.57196 |

15.64089521 |

7.13 |

< 0.0001 |

|

Age |

-0.254749 |

0.22871957 |

-1.11 |

0.2671 |

| Prostate Volume | -0.198787 | 0.07516895 | -2.64 | 0.0091 |

When modeled with EPIC UI scores at 3 years post-SBRT, age was not highly correlated with the UI outcome (p = 0.2671, Table 5). From a bivariate relationship, prostate volume and α1A antagonist usage are highly associated with the outcome, although after adjusting for age, only the prostate volume was highly associated with UI score (p = 0.0091, Table 5). No other baseline patient characteristics were significantly associated with UI score at three years following SBRT.

Discussion

Urinary incontinence following prostate cancer treatment is common [35] and an important quality of life issue [8]. A better understanding of the risk of UI following SBRT enables clinicians to provide more realistic expectations to patients as they weigh complex treatment options [36]. Currently, there is limited data on incidence of UI following SBRT for prostate cancer [22]. Previously, we reported a 10-15% risk of UI following SBRT. However, these findings relied on physician reported UI rates, which may under report the actual incidence of UI and provided no information on the associated bother [11]. In this study, we utilized the urinary incontinence domain of the EPIC-26 to comprehensively evaluate patient reported UI following SBRT [31].

The incidence of post treatment UI varies greatly depending on the definition utilized [10]. In the absence of a consensus definition of UI, direct comparison between treatment techniques remains difficult. The most commonly used definition of UI is daily pad usage [37]; however, even “pad free” men may experience periodic leakage. Likewise, men using only one pad per day may be using it due to frequent leakage or as a precaution [32,38-40]. Thus for this analysis, we evaluated the three commonly used definitions to assess the incidence and associated dysfunction. In addition, we examined the bother associated with UI (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation between urinary incontinence bother and urinary incontinence definition at three years post-SBRT

| No problem | Small problem | Moderate-big problem | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Leak > Once/day |

0.0% |

33.3% |

66.7% |

|

Frequent dribbling |

20.0% |

20.0% |

60.0% |

|

Any pad usage |

5.9% |

58.8% |

35.3% |

| EPIC UI summary “Severe” (0-49) | 0.0% | 18.2% | 81.8% |

As in other radiation therapy series, our patients were elderly with poor baseline urinary function and a high prevalence of UI prior to treatment [8]. At one month post-treatment there was an acute increase in UI that resolved by three months post SBRT. This acute increase was likely secondary to transient cystitis/urethritis, which when moderate to severe may cause urge incontinence [41]. As observed previously following treatment with alternative radiation modalities [8,9,42,43], a second gradual increase in UI occurred from 3 months to the end of follow-up without recovery. Even so, by three years post-SBRT, only 6% of these patients reported leaking more than once per day and only 5% reported needing more than one pad per day. Despite the high biologically effective dose (BED) delivered by SBRT in this series, these results seem similar to conventionally fractionated EBRT, proton therapy and brachytherapy [8,44]. It seems to be that despite the fact that patients in this study are older and have more comorbidities, the incontinence rates compare favorably to radical prostatectomy [8].

The etiology of late UI following prostate cancer radiation therapy appears to be multi-factorial [35], and is likely due in part to aging and related comorbidities [42]. Prostate cancer itself may impair the integrity of the anatomic structures that maintain urinary continence. When compared to their peers without prostate cancer, even men who choose active surveillance are at increased risk of UI [37,45,46]. Previous studies of alternative radiation modalities have also reported that late toxicity following radiation therapy is associated with pretreatment factors related to BPH, such as a high AUA score [47,48] and a large prostate volume [49]. Post-RT TURP may increase the incidence of urinary incontinence [50]. In this series, late UI secondary to post-RT TURP was rare. The one patient who experienced this had a history of benign prostatic hypertrophy with a large prostate and two prior TURP procedures prior to receiving SBRT [22].

Compared with urinary function, bother may be a more accurate indicator of the impact of treatment on an individual patient’s quality of life. Defined as the degree of interference or annoyance caused by urinary incontinence, bother is dependent on an individual’s pretreatment function [51,52]. In general, previously continent men report higher rates of post-treatment bother. In this series of men, UI bother gradually increased during the first three years following SBRT treatment (Figure 2, Table 4). Two years following SBRT, 6% of men reported UI bother as a moderate to big problem. This change is comparable to that reported at 24 months with conventionally fractionated IMRT (5%), proton therapy (4%) and brachytherapy (6%) [8,44].

Commonly employed UI definitions based on answers to single questions do not fully assess the clinical impact of urinary incontinence (i.e., symptom, dysfunction and bother). Domain summary scores more comprehensively assess the clinical impact of UI on the patient [31]. Our EPIC UI summary domain outcomes appear similar to those previously reported for high dose conventionally fractionated intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT)/proton therapy and brachytherapy [8,9]. The mean urinary incontinence score change from baseline at 24 months was – 4.7. This change from baseline was statistically significant but not clinically significant. Importantly, this change is comparable to that seen at 24 months with IMRT, proton therapy and brachytherapy, − 5.1, −4.1 and −6.0 respectively [8,9].

Conclusions

SBRT for clinically localized prostate cancer was well tolerated with UI rates comparable to conventionally fractionated external radiotherapy and brachytherapy. More than 90% of men who were pad-free prior to treatment remained pad-free three years following treatment. Less than 10% of men felt post-treatment UI was a moderate to big problem at any time point following treatment. Longer term follow-up is needed to confirm late effects.

Consent

This retrospective review of prospectively collected data was approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board.

Abbreviations

ADT: Androgen deprivation therapy; AUA: American Urological Association; BED: Biologically effective dose; BPH: Benign prostatic hyperplasia; CT: Computed tomography; CTV: Clinical target volume; DVH: Dose-volume histogram; EQD2: Equivalent dose in 2-Gy fractions; EPIC: Expanded Prostate Index Composite; GTV: Gross target volume; Gy: Gray; IMRT: Intensity modulated radiation therapy; IRB: Internal Review Board; PTV: Planning target volume; QoL: Quality of life; MID: Minimally important difference; MR: Magnetic resonance; SD: Standard deviation; SF-12: Short Form-12 Health Survey; SBRT: Stereotactic body radiation therapy; UI: Urinary incontinence.

Competing interests

SP Collins and BT Collins serve as clinical consultants to Accuray Inc. The Department of Radiation Medicine at Georgetown University Hospital receives a grant from Accuray to support a research coordinator. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LC and SS are lead authors, who participated in data collection, data analysis, manuscript drafting, table/figure creation and manuscript revision. HW participated in data analysis and manuscript drafting, table/figure creation and manuscript revision. AB and JW aided in the quality of life data collection and maintained the patient database. RM and JK aided in the quality of life data collection and maintained the patient database. TY aided in clinical data collection. SL is the dosimetrist who developed the majority of patients’ treatment plans, and contributed to the dosimetric data analysis and interpretation. BC and KK participated in the design and coordination of the study. AD is a senior author who aided in drafting the manuscript. JL is a senior author who aided in drafting the manuscript. SC was the principal investigator who initially developed the concept of the study and the design, aided in data collection, drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Leonard N Chen, Email: lnc@georgetown.edu.

Simeng Suy, Email: suys@georgetown.edu.

Hongkun Wang, Email: hw87@georgetown.edu.

Aditi Bhagat, Email: abhagat@gwmail.gwu.edu.

Jennifer A Woo, Email: jaw98@georgetown.edu.

Rudy A Moures, Email: rudy.a.moures@gunet.georgetown.edu.

Joy S Kim, Email: jsk64@georgetown.edu.

Thomas M Yung, Email: thomas.m.yung@gunet.georgetown.edu.

Siyuan Lei, Email: siyuan.lei@gunet.georgetown.edu.

Brian T Collins, Email: collinsb@gunet.georgetown.edu.

Keith Kowalczyk, Email: keith.kowalczyk@gunet.georgetown.edu.

Anatoly Dritschilo, Email: dritscha@gunet.georgetown.edu.

John H Lynch, Email: lynchj@gunet.georgetown.edu.

Sean P Collins, Email: SPC9@gunet.georgetown.edu.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the James and Theodore Pedas Family Foundation and NIH Grant P30CA051008.

References

- Anger JT, Saigal CS, Stothers L, Thom DH, Rodriguez LV, Litwin MS. The prevalence of urinary incontinence among community dwelling men: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. J Urol. 2006;176:2103–2108. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.029. discussion 2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong E, Nitti VW. Urinary incontinence. Prim Care. 2010;37:599–612. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2010.04.008. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamliyan TA, Wyman JF, Ping R, Wilt TJ, Kane RL. Male urinary incontinence: prevalence, risk factors, and preventive interventions. Rev Urol. 2009;11:145–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficarra V, Novara G, Rosen RC, Artibani W, Carroll PR, Costello A, Menon M, Montorsi F, Patel VR, Stolzenburg JU, van der Poel H, Wilsonn TG, Zattoni F, Mottrie A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62:405–417. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin KR, Prasad MM. Post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence: a confluence of 3 factors. J Urol. 2010;183:871–877. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson CE, Pettersson N, Alsadius D, Wilderang U, Tucker SL, Johansson KA, Steineck G. Patient-reported genitourinary toxicity for long-term prostate cancer survivors treated with radiation therapy. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1964–1970. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tol-Geerdink JJ, Leer JW, van Oort IM, van Lin EJ, Weijerman PC, Vergunst H, Witjes JA, Stalmeier PF. Quality of life after prostate cancer treatments in patients comparable at baseline. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1784–1789. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, Lin X, Greenfield TK, Litwin MS, Saigal CS, Mahadevan A, Klein E, Kibel A, Pisters LL, Kuban D, Kaplan I, Wood D, Ciezki J, Shah N, Wei JT. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PJ, Paly JJ, Yeap BY, Sanda MG, Sandler HM, Michalski JM, Talcott JA, Coen JJ, Hamstra DA, Shipley WU, Hahn SM, Zietman AL, Bekelman JE, Efstathiou JA. Patient-reported outcomes after 3-dimensional conformal, intensity-modulated, or proton beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1729–1735. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupski TL, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. Variation in continence and potency by definition. J Urol. 2003;170:1291–1294. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000085341.63407.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonn GA, Sadetsky N, Presti JC, Litwin MS. Differing perceptions of quality of life in patients with prostate cancer and their doctors. J Urol. 2013;189:S59–S65. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.032. discussion S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko Y, Lin SJ, Salmon JW, Bron MS. The impact of urinary incontinence on quality of life of the elderly. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S103–S111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DE, Milsom I, Kopp Z, Abrams P, Artibani W, Herschorn S. Prevalence, severity, and symptom bother of lower urinary tract symptoms among men in the EPIC study: impact of overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2009;56:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco E, Prayer-Galetti T, Pinto F, Fracalanza S, Betto G, Pagano F, Artibani W. Urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy: incidence by definition, risk factors and temporal trend in a large series with a long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2006;97:1234–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SS, Link CL, Tennstedt SL, Kusek JW, McKinlay JB. Care seeking and treatment for urinary incontinence in a diverse population. J Urol. 2007;177:680–684. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothers L, Thom D, Calhoun E. Urologic diseases in America project: urinary incontinence in males–demographics and economic burden. J Urol. 2005;173:1302–1308. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000155503.12545.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JF. The radiobiology of prostate cancer including new aspects of fractionated radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2005;44:265–276. doi: 10.1080/02841860410002824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter M, Forman J, Kupelian P, Lawton C, Petereit D. Hypofractionation for prostate cancer. Cancer J. 2009;15:1–6. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181976614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CR, Brooks JD, Gill H, Presti JC Jr. Long-term outcomes from a prospective trial of stereotactic body radiotherapy for low-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;82:877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz AJ, Santoro M, Diblasio F, Ashley R. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: disease control and quality of life at 6 years. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:118. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman DE, King CR. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for low-risk prostate cancer: five-year outcomes. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LN, Suy S, Uhm S, Oermann EK, Ju AW, Chen V, Hanscom HN, Laing S, Kim JS, Lei S, Batipps GP, Kowalczyk K, Bandi G, Pahira J, McGeagh KG, Collins BT, Krishnan P, Dawson NA, Taylor KL, Dritschilo A, Lynch JH, Collins SP. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Georgetown University experience. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride SM, Wong DS, Dombrowski JJ, Harkins B, Tapella P, Hanscom HN, Collins SP, Kaplan ID. Hypofractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy in low-risk prostate adenocarcinoma: preliminary results of a multi-institutional phase 1 feasibility trial. Cancer. 2012;118:3681–3690. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CR, Freeman D, Kaplan I, Fuller D, Bolzicco G, Collins S, Meier R, Wang J, Kupelian P, Steinberg M, Katz A. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: pooled analysis from a multi-institutional consortium of prospective phase II trials. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CR, Collins S, Fuller D, Wang PC, Kupelian P, Steinberg M, Katz A. Health-related quality of life after stereotactic body radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer: results from a multi-institutional consortium of prospective trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:939–945. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S, Piel N, Oermann EK, Chen V, Ju AW, Dahal KN, Hanscom HN, Kim JS, Yu X, Zhang G, Collins BT, Jha R, Dritschilo A, Suy S, Collins SP. Six-dimensional correction of intra-fractional prostate motion with CyberKnife stereotactic body radiation therapy. Front Oncol. 2011;1:48. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2011.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainshtein J, Abu-Isa E, Olson KB, Ray ME, Sandler HM, Normolle D, Litzenberg DW, Masi K, Pan C, Hamstra DA. Randomized phase II trial of urethral sparing intensity modulated radiation therapy in low-risk prostate cancer: implications for focal therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Djajaputra D, King CR, Hossain S, Ma L, Xing L. Intrafractional motion of the prostate during hypofractionated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, Bruskewitz RC, Holtgrewe HL, Mebust WK, Cockett AT. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. discussion 1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielb S, Dunn RL, Rashid MG, Murray S, Sanda MG, Montie JE, Wei JT. Assessment of early continence recovery after radical prostatectomy: patient reported symptoms and impairment. J Urol. 2001;166:958–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison JS, He C, Wood DP. Stratification of postprostatectomy urinary function using expanded prostate cancer index composite. Urology. 2013;81:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grise P, Thurman S. Urinary incontinence following treatment of localized prostate cancer. Cancer Control. 2001;8:532–539. doi: 10.1177/107327480100800608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symon Z, Daignault S, Symon R, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, Sandler HM. Measuring patients’ expectations regarding health-related quality-of-life outcomes associated with prostate cancer surgery or radiotherapy. Urology. 2006;68:1224–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp RP, Marshall LM, Wang PY, Bauer DC, Barrett-Connor E, Parsons JK. The burden of urinary incontinence and urinary bother among elderly prostate cancer survivors. Eur Urol. 2013;64:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepor H, Kaci L, Xue X. Continence following radical retropubic prostatectomy using self-reporting instruments. J Urol. 2004;171:1212–1215. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110631.81774.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstedt A, Carlsson S, Nilsson AE, Johansson E, Nyberg T, Steineck G, Wiklund NP. Pad use and patient reported bother from urinary leakage after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2012;187:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WS, Shikanov SA, Katz MH, Zagaja GP, Shalhav AL, Zorn KC. Analysis of continence rates following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: strict leak-free and pad-free continence. Urology. 2010;75:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.07.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosnitz RG, Schneider L, Manola J, Rocha S, Loffredo M, Lopes L, D’Amico AV. Tamsulosin palliates radiation-induced urethritis in patients with prostate cancer: results of a pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:563–566. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, Albertsen PC, Goodman M, Hamilton AS, Hoffman RM, Potosky AL, Stanford JL, Stroup AM, Van Horn RL, Penson DF. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen JJ, Paly JJ, Niemierko A, Weyman E, Rodrigues A, Shipley WU, Zietman AL, Talcott JA. Long-term quality of life outcome after proton beam monotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e201–e209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe BS, Nichols RC, Henderson RH, Morris CG, Williams CR, Costa J, Marcus RB Jr, Mendenhall WM, Li Z, Mendenhall NP. Erectile function, incontinence, and other quality of life outcomes following proton therapy for prostate cancer in men 60 years old and younger. Cancer. 2012;118:4619–4626. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, Johansson JE, Nyberg T, Ruutu M, Bill-Axelson A. Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:891–899. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman J, Litwin MS. Quality of life in men undergoing active surveillance for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:242–249. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik R, Jani AB, Liauw SL. External beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: urinary outcomes for men with high International Prostate Symptom Scores (IPSS) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes M, Miller S, Moravan V, Pickles T, McKenzie M, Pai H, Liu M, Kwan W, Agranovich A, Spadinger I, Lapointe V, Halperin R, Morris WJ. Predictive factors for acute and late urinary toxicity after permanent prostate brachytherapy: long-term outcome in 712 consecutive patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:1023–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsolia A, Vargas C, Yan D, Brabbins D, Lockman D, Liang J, Gustafson G, Vicini F, Martinez A, Kestin LL. Predictors for chronic urinary toxicity after the treatment of prostate cancer with adaptive three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy: dose-volume analysis of a phase II dose-escalation study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1100–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama H, Hirayama T, Jhaveri P, Satoh T, Paulino AC, Xu B, Butler EB, Teh BS. Is there an increase in genitourinary toxicity in patients treated with transurethral resection of the prostate and radiotherapy?: a systematic review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:297–304. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182546821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin MS, Gore JL, Kwan L, Brandeis JM, Lee SP, Withers HR, Reiter RE. Quality of life after surgery, external beam irradiation, or brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:2239–2247. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore JL, Gollapudi K, Bergman J, Kwan L, Krupski TL, Litwin MS. Correlates of bother following treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2010;184:1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]