Abstract

Sexual satisfaction is an integral component of sexual health and well-being, yet we know little about which factors contribute to it among lesbian/bisexual women. To examine a proposed ecological model of sexual satisfaction, we conducted an internet survey of married heterosexual women and lesbian/bisexual women in committed same-sex relationships. Structural equation modeling included five final latent variables for heterosexual women and seven final latent variables for lesbian/bisexual women. Overall, results indicated that, for both groups of women, a similar constellation of factors (depressive symptoms, relationship satisfaction, sexual functioning, and social support) was related to sexual satisfaction. In lesbian/bisexual women, internalized homophobia was an additional factor. Contrary to expectations, the presence of children in the home and a history of childhood sexual abuse did not contribute significantly to the model for either group. Findings support the idea that gender socialization may influence sexual satisfaction more than socialization around sexual orientation. Additionally, given that for both groups of women relationship satisfaction explained a substantial amount of variance in sexual satisfaction, sexual concerns may be better addressed at the relationship than the individual level.

Keywords: Sexual satisfaction, Women, Lesbian, Ecological model

Introduction

Sexual satisfaction is an integral component of sexual health and well-being. Despite its contextual nature, sexual satisfaction is often considered solely in terms of physiology, based on the medical model of sexual functioning popularized by Masters and Johnson (1970; see also Rosen & Leiblum, 1995). Rarely is sexual satisfaction conceptualized, studied, or treated within the context of a relationship. Moreover, when sexuality is studied in a relational context, the majority of this research has focused on heterosexual men and women, most often in the context of marriage. Research on other relationships is less common, and comparable studies using same-sex couples are rare (Clark & Serovich, 1997; Martell, Safren, & Prince, 2004).

Women, in particular, appear to regard sexuality from a relational orientation in which sexuality is viewed as one aspect of an intimate relationship (Waite & Joyner, 2001). Therefore, an encompassing theory of female sexuality needs to consider the larger relationship context and it needs to address all women, not merely heterosexual women. Though the etiology of sexual orientation remains unknown, especially in women, we do know that irrespective of gender-atypical experiences, attitudes, or overt sexual orientation, most children of the same sex appear to be socialized in a similar manner from birth through childhood (Bailey, Gaulin, Agyei, & Gladue, 1994).

Studies assessing the association of sexual orientation and gendered behaviors with sexual variables have found mixed results. One study found that gender had a greater impact on sexual attitudes and behaviors than did sexual orientation (Bailey et al., 1994). In other words, while there were some differences attributable to the effects of sexual orientation, lesbian women were more like heterosexual women than gay men, and gay men responded more like heterosexual men than lesbian women. Further, in a recent study, similar proportions of lesbian and heterosexual women reported high levels of sexual satisfaction in their relationship (Matthews, Tartaro, & Hughes, 2003).

While some studies identified domains in which lesbian women responded more similarly (than dissimilarly) to heterosexual women, others have determined differences in lesbian and heterosexual women’s attitudes and behaviors toward sex and intimate relationships. For example, lesbian women reported finding visual sexual stimuli (visual erotica) more stimulating (Bailey et al., 1994) and reported that sex was a more important factor in their satisfaction than did heterosexual women (Matthews et al., 2003). Contrary to some previous research (Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983), lesbian women did not report lower frequencies of sexual behaviors (Matthews et al., 2003). In relationships, lesbian women reported a greater flexibility in the roles each partner might take, as well as greater equality within the relationship relative to a heterosexual comparison group (Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983; Kurdek, 1987). Also, lesbian women in relationships reported that affectionate behaviors, such as cuddling or snuggling, are ends unto them selves, not necessarily precursors to intercourse, as heterosexual couples often regard them (Huston & Schwartz, 1995).

Ecological Theory

Ecological theory provided the overarching framework of this study. Previous research findings will be discussed within a larger framework of an ecological model. Paramount to ecological theory is the interaction between an individual and other individuals, objects, and social forces in the environment (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). When extended to social systems, ecological theory allows for conceptualization at multiple levels, not just at the level of the individual. Such a theory considers the importance of environmental and societal conditions on individual functioning. Ecological theory defines layers of environment in relation to a variable studied, moving from proximal to distal factors. It allows for interactions between layers and anticipates that layers will affect one another (Pillari & Newsom, 1998).

First, there is a microsystem, or the individual level. This layer of analysis accounts for individual differences as well as an individual’s beliefs, values, and emotions. One layer removed from the microsystem is the mesosystem. This system includes intimate relationships, often with a spouse or partner. The exosystem is another layer removed from the individual, and reflects larger, less direct factors that may influence the mesosystem as well as an individual’s beliefs or behavior, such as extended family and social support networks. Finally, the macrosystem is the farthest removed from the individual and contains institutional and societal factors, including laws, ideologies, and widely held cultural beliefs.

As previous research has shown, conceptualizing sexual satisfaction from multiple perspectives may produce a more accurate understanding of the factors that influence sexual satisfaction, especially among women. Feminist psychological theorists commend ecological theory for providing a more accurate portrayal of women living in a patriarchal society (Ballou, Matsumoto, & Wagner, 2002). Indeed, ecological models enable theorists to consider an individual beyond the paradigm validated on the middle-class, Caucasian, heterosexual male and can account for effects of sexism, racism, and homophobia and for interactions among factors at varying levels of analysis.

In the present study, we considered factors at the microsystem (i.e., depression, child sexual abuse, internalized homophobia); mesosystem (i.e., relationship satisfaction, sexual functioning); and exosystem (i.e., social support, parenthood) levels as they may influence sexual satisfaction for lesbian and heterosexual women. These particular variables were considered in the present model due to prior studies that suggested their relationship with sexual satisfaction. Moreover, we were interested in taking factors into account at each of the above levels in the ecological framework. In the next sections, we review the relevant literature for each of these factors.

Microsystem Level

Depression

Depressive symptoms often have a negative impact on sexual functioning. Studies show that among depressed individuals, the rates of comorbid sexual dysfunction are significantly higher than in non-depressed individuals (Baldwin, 2001; Clayton, 2001). Upwards of 70% of individuals diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder report some detriment to their sexual functioning (Clayton, 2001). Women who endorse depressive symptoms also report lower levels of sexual satisfaction overall (Cyranowski et al., 2003).

Furthermore, there is a well-documented relationship between depression and relationship dissatisfaction in heterosexual married couples (for a review, see Whisman, 2001). Although this relationship is widely accepted, researchers have yet to determine any causal direction (Cramer, 2004; Whisman & Bruce, 1999). Many note that depressive symptoms, diminished interest in pleasurable activities, and general anhedonia may exacerbate poor relationship functioning or serve to maintain low levels of relationship satisfaction (Baldwin, 2001; Ferguson, 2001). In a national survey, the association between marital dissatisfaction and depression appeared more salient for women than for men, even when controlling for previous depressive symptoms (Whisman & Bruce, 1999).

Interestingly, the well-established connection between depression and relationship satisfaction may not be present in the lesbian population. Lesbian women may be at a greater risk for depression, facing additional stressors due to their sexual orientation to which heterosexual women are not exposed (Tait, 1997). However, involvement in a romantic relationship may serve as a protective factor against depression in lesbian women (Ayala & Coleman, 2000; Oetjen & Rothblum, 2000). Support for this idea remains equivocal. Lesbian women who reported few depression symptoms also reported greater relationship satisfaction (Kurdek, 1993). However, one study found that while satisfaction with one’s relationship status was significantly correlated with depression, overall relationship satisfaction was not significantly associated with depression (Oetjen & Rothblum, 2000). Further studies may help clarify the relationship between depression and relationship satisfaction.

Child Sexual Abuse

Child sexual abuse is related to anindividual’s personal history and is thus considered at the individual level (Small & Luster, 1994). Research on the impact of child sexual abuse on sexual functioning in adulthood is somewhat variable. Some studies have found that childhood sexual abuse correlates with minimal problems in adulthood, while others have reported more significant impairment in adult functioning (for a review, see Loeb et al., 2002; Najman et al., 2005). For example, studies have found that upwards of 85% of women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse also report some level of sexual problems (Gorcey, Santiago, & McCall-Perez, 1986). Several studies have found that among childhood sexual abuse victims, nearly half of the women meet DSM-IV criteria for at least one sexual dysfunction (Leonard & Follette, 2002; Loeb et al., 2002). Among women who report a greater severity of sexual abuse (multiple incidents of sexual abuse rather than one incident), there is a concomitant report of greater sexual problems, particularly sexual desire or sexual arousal problems or delay or absence of orgasm (Kinzl, Traweger, & Biebl, 1995). Additionally, survivors of childhood sexual abuse also report lower levels of sexual satisfaction within their relationships (DiLillo, 2001; Leonard & Follette, 2002; Loeb et al., 2002; Rellini & Meston, 2007). Some of the inconsistency in results in this literature can be attributed to variance in definitions of sexual abuse. Theorists and researchers refer to different types of sexual behavior, age limits, and criteria that define an incident as abuse and these factors may differentially impact later sexual functioning (Loeb et al., 2002; Rellini & Meston, 2007).

Because of differing definitions, prevalence reports of childhood sexual abuse also vary. Rates of childhood sexual abuse in women range from 7% to 36% (Finkelhor, 1994). Women are one and one-half to three times more likely to be victims of childhood sexual abuse than are men. Among women, significant differences have been found in the rates of childhood sexual abuse according to sexual orientation, with 42–43% of lesbians and 25–27% of heterosexuals reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse (Hughes, Johnson, & Wilsnack, 2001; Tomeo, Templer, Anderson, & Kotler, 2001).

Internalized Homophobia

Internalized homophobia, or a gay or lesbian person’s internalization of society’s negative attitudes toward gay and lesbian individuals, is a suggested cause of distress for many lesbian women and gay men (Williamson, 2000). High rates of internalized homophobia have been associated with substance abuse, eating disorders, and suicidality (Meyer, 2003). Additionally, internalized homophobia is correlated with depressive symptomatology and anxiety symptoms (Williamson, 2000). Though there is an association between relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction, this research has looked at gay men, often within an HIV prevention framework (Ross & Rosser, 1996). While there is evidence that internalized homophobia may have negative associations with relationship and sexual satisfaction in gay men, there has been little research with lesbian women. One study did find an inverse relationship between internalized homophobia and relationship satisfaction (Balsam, 2002), but further research is necessary to further establish this association.

Mesosystem Level

Relationship Satisfaction

Several researchers have examined heterosexual and lesbian couples on factors related to relationship satisfaction. Cohabiting (but unmarried) heterosexual couples typically report lower levels of relationship satisfaction than lesbian and married couples, who report equivalent levels of satisfaction (Duffy & Rusbult, 1985; Gottman et al., 2003).

Early in comparative research, it was speculated that lesbian couples would report lower levels of relationship satisfaction than heterosexual couples because the former received less societal and institutional support for their relationships. Additionally, lesbian couples may have less social support from non-accepting friends and family, which may result in decreased relationship satisfaction (Peplau, Padesky, & Hamilton, 1982). However, as a general rule, speculations of decreased relationship satisfaction have not been supported (Duffy & Rusbult, 1985; Peplau, 1991). In fact, one study found that lesbian women reported greater relationship satisfaction than did heterosexual women (Kurdek, 1989). A study comparing lesbian and heterosexual couples stated that the two couple types were more alike than they were different on dimensions of relationship satisfaction (Kurdek, 1987).

Further, relationship satisfaction has been shown to be significantly associated with sexual satisfaction both in heterosexual couples as well as in lesbian couples (Byers, 2005; Mackey, Diemer, & O’Brien, 2000). Indeed, over 90% of the lesbian women participants in one study reported high levels of intimacy and relationship satisfaction if they also reported a positive sexual relationship and high levels of physical affection (Mackey et al., 2000).

Sexual Functioning

Sexual functioning is a mesosystem variable in that it occurs within the context of a relationship (that is, it is one step removed from the individual level). Sexual satisfaction is significantly related to sexual frequency in heterosexual couples. Couples that report having sex more frequently also report higher levels of sexual satisfaction (Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). Studies have found that sexual frequency in married couples decreases over time, but that both men and women still report high levels of sexual satisfaction (Christopher & Sprecher, 2000).

Sexual satisfaction is also associated with an individual’s sexual concerns. In a study looking at married couples, a majority of women reported at least one sexual concern or problem (MacNeil & Byers, 1997). Reporting any sexual concerns or sexual problems was inversely related to sexual satisfaction. In a different study, female reports of low sexual desire (i.e., Hypoactive Desire Disorder) were significantly related to decreased sexual satisfaction. Also, heterosexual women who reported decreased intimacy and affection reported decreased sexual desire and decreased sexual satisfaction (Davies, Katz, & Jackson, 1999), and this was also found among lesbian women (Kathleen & Junginger, 2007). Taken together, a comprehensive perspective of sexual functioning, including sexual frequency, desire, sexual concerns, and related domains, appears to be significantly related to sexual satisfaction.

Exosystem Level

Social Support

Cutrona (1996) predicted that during stressful events within a relationship, support for that relationship helps prevent isolation from one’s partner, as well as promotes a sense of connectedness within the couple. There is evidence that couples who feel supported report higher degrees of relationship satisfaction (Julien, Chartrand, Simard, Bouthilier, & Begin, 2003). Jordan and Deluty (2000) found that lesbian couples who reported greater perceived social support also reported greater satisfaction in their relationship. Nonetheless, in lesbian relationships, couples may have less support from their families. Murphy (1989) assessed the impact of parental attitudes on lesbian women’s relationships. Perceived parental attitudes about the couple had no significant impact on relationship quality. While having support from one’s parents can serve to strengthen the relationship, for the women in the study, even parental disapproval was outweighed by the positive experience of disclosing about their relationship (Murphy, 1989).

Parenthood

Couples who become parents face different factors than childfree couples that affect their satisfaction with the relationship. While the rewards from having a child may be immense, research suggests there is a significant decline in relationship satisfaction after the birth of the first child in heterosexual couples (Shapiro, Gottman, & Carrere, 2000). It may be that this decrease in satisfaction is attributable to a substantial decrease in time spent by the couple sharing companionate activities. Also, there is often a decrease in positive communication between parents and an increase in conflict (Shapiro et al., 2000). Moreover, a large study with first-time parents found that parenting impacted couples’ dyadic sexuality, such as engaging in sex less frequently (Ahlborg, Dahlof, & Hallberg, 2005). Unfortunately, there exists no comparable research looking at how raising children affects the relationships of lesbian couples. The little available research on gay and lesbian parents demonstrates they are similar to heterosexual parents in their commitment to raising their families (Hare, 1994).

The Present Study

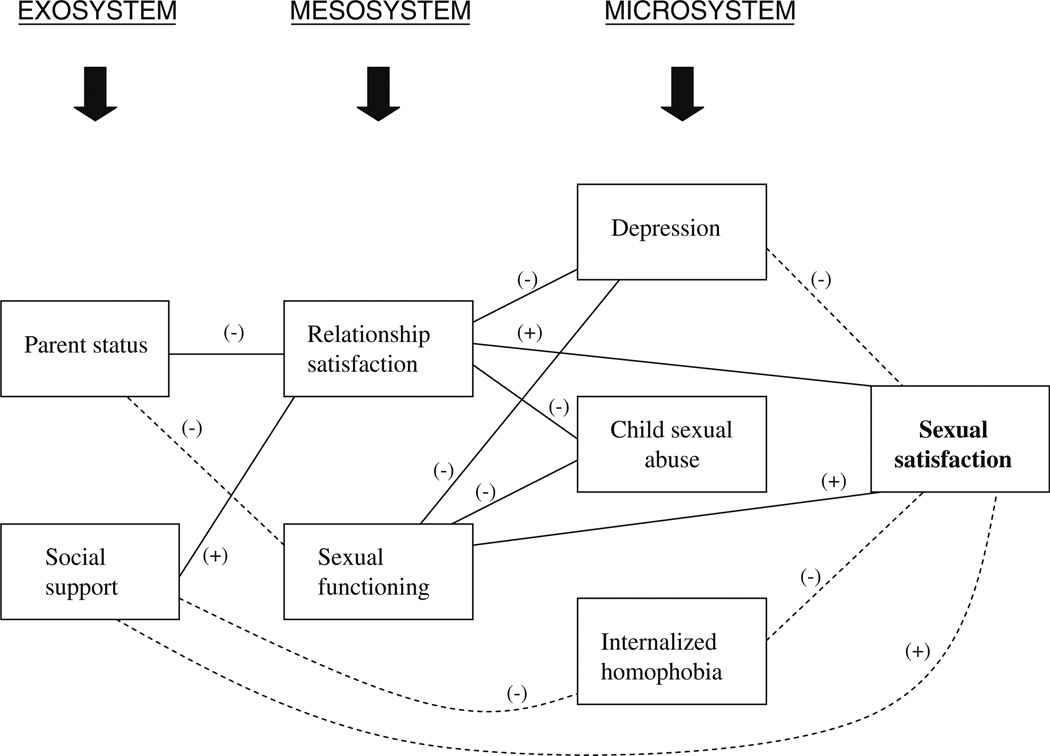

Based on the literature and clinical practice, we developed an ecological model of sexual satisfaction that considered factors at three system levels and attempts to explain the relationship among these levels (see Fig. 1). The outcome of sexual satisfaction was conceptualized at the individual or microsystem level, defined as an individual’s subjective evaluation of her sexual relationship.

Fig. 1.

Proposed ecological model of female sexual satisfaction. Solid lines indicate relationships supported by previous studies. Dashed lines indicate relationships hypothesized by the current study, but not validated by previous studies

At the individual or microsystem level, we anticipated that depressive symptoms as well as a history of childhood sexual abuse would affect sexual satisfaction, directly or indirectly. Both of these variables have been shown to have a negative impact on functioning in women, and it was proposed that the relationship would be maintained in this model. Additionally, in lesbian women, it was predicted that higher rates of internalized homophobia would have an inverse relationship with sexual satisfaction.

At the relationship or mesosystem level, two variables were considered to impact sexual satisfaction: relationship satisfaction and sexual functioning. These two variables were placed at the mesosystem level because they reflect perceptions or behaviors that involve an intimate partner. The association between relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction has been well established for women, and we anticipated that this robust finding would be maintained in the present study.

Finally, at the exosystem or social network level of analysis, social support and parenthood were included in the model. Research has shown that individuals who feel supported by friends or family also report higher levels of relationship satisfaction, and we hypothesized that it may be associated with sexual satisfaction as well. It was proposed that, in lesbian women, social support would be negatively associated with internalized homophobia, a microsystem level variable; internalized homophobia may, in turn, contribute to decreased sexual satisfaction. Also, parenthood status was added at the exosystem level, recognizing that the presence of children in the home has an inverse relationship with relationship satisfaction in married heterosexual couples, and may negatively impact sexual functioning (e.g., sexual frequency and desire). This model looked for similar effects in lesbian couples for the first time in the literature. The primary goal of this study was to determine if the ecological model described above provided an accurate description of sexual satisfaction in women. Many of the relationships suggested by the proposed model of sexual satisfaction have been previously supported by prior empirical research (denoted by solid lines in Fig. 1). This study served to replicate these previous findings and test their relations to one another. Additionally, this study investigated relationships between variables thathavenot been confirmed by previous research, but were thought necessary to better understand female sexual satisfaction (denoted by dashed lines in Fig. 1). Relationships between these proposed variables were examined through structural equation modeling.

Finally, the overall model was assessed to determine its ability to explain sexual satisfaction on the basis of sexual orientation. Specifically, sexual orientation was thought to moderate the relationship among the variables proposed in the model. Again, the factor of internalized homophobia is unique to the lesbian participants and, for this subgroup, the model was tested to determine how the addition of this variable contributes to an understanding of sexual satisfaction for lesbian women.

Method

Participants

This study was conducted online and participants were recruited primarily via the Internet. Inclusion criteria stipulated that heterosexual women needed to be married and living with their husbands for at least one year. Lesbian women had to be living with their partner for at least one year and identify their relationship as monogamous and committed. We requested participation be limited to one member of the couple. Participants were recruited via newspaper advertisements, online advertisements, posted fliers, and advertisements on e-mail listservs that directed women to the study website. Specifically, we posted announcements on Craigslist, queer aliases at Microsoft and Amazon, and a gay and lesbian listserv at the University of Washington. Lesbian participants with children were targeted through advertisements with gay and lesbian parenting groups and listservs.

The questionnaire for the study was posted online. Aside from the five copies that were printed from the website and mailed to the principal investigator, no paper copies were distributed or otherwise collected. The dedicated study website explained the study in detail and provided an information statement that served as an online consent form. After consenting, women could complete the entire study online.

A total of 253 women completed the study, consisting of 139 married heterosexual women and 114 lesbian/bisexual women. Eighty-five percent of the heterosexual women and 83% of the lesbian/bisexual women were Caucasian and a majority of the participants had a 4-year college degree and were employed full time (see Table 1). Over 90% of the participants were from the greater Puget Sound Metropolitan area (i.e., Seattle proper and its surrounding suburbs).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics for heterosexual and lesbian/bisexual women in relationships

| Heterosexual (n = 139) |

Lesbian/Bisexual (n = 114) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % | χ2 |

| Ethnicity | 7.25 | ||||

| Latina | 5 | 3.6 | 4 | 3.5 | |

| African American | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Asian | 7 | 5.0 | 4 | 3.5 | |

| American Indian | 3 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Caucasian | 118 | 84.9 | 94 | 82.5 | |

| Other | 6 | 4.3 | 10 | 8.8 | |

| Education | 2.59 | ||||

| <High school | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| High school degree | 4 | 2.9 | 4 | 3.5 | |

| Some college | 32 | 23.0 | 22 | 19.3 | |

| 2-yr. Degree | 9 | 6.5 | 8 | 7.0 | |

| 4-yr. Degree | 57 | 41.0 | 46 | 40.4 | |

| Graduate degree | 27 | 19.4 | 29 | 25.4 | |

| Vocational training | 8 | 5.8 | 5 | 4.4 | |

| Employment status | 33.95*** | ||||

| Employed full-time | 59 | 42.4 | 65 | 57.0 | |

| Employed part-time | 8 | 5.8 | 17 | 14.9 | |

| Work at home | 17 | 12.2 | 5 | 4.4 | |

| Homemaker | 24 | 17.3 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Student | 22 | 15.8 | 15 | 13.2 | |

| Unemployed | 7 | 5.0 | 10 | 8.8 | |

| Annual Income | 17.34 | ||||

| <$30,000 | 12 | 8.6 | 32 | 28.1 | |

| <60,000 | 40 | 28.8 | 27 | 23.7 | |

| <90,000 | 38 | 27.3 | 25 | 21.9 | |

| ≥90,000 | 49 | 35.3 | 30 | 26.3 | |

| M | SD | M | SD | t test | |

| Age (in years) | 32.9 | 7.67 | 33.4 | 8.31 | −.51 |

| Range | 19–61 | 20–62 | |||

| Age of partner (in years) | 34.8 | 6.95 | 33.5 | 8.79 | 1.32 |

| Range | 22–54 | 20–59 | |||

| Duration of relationship (in years) | 8.1 | 5.33 | 4.87 | 4.55 | 5.11*** |

| Range | 1–26 | 1–25 | |||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Measures

Sociodemographics

Participants were asked to provide the following demographic information: biological sex, sexual orientation, age, level of education, current occupation, length of marriage/relationship, length of time living with partner, number of children, and number of children living in the home.

Depressive Symptomatology

The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CESD; Radloff, 1977) is a well-validated and widely used inventory that assesses an individual’s current level of depressive symptoms. The CESD consists of 20 items assessing the frequency of depressive symptoms in the past two weeks (from “rarely or none of the time” to “most or all of the time”). The scale has four subscales: depressive affect, positive affect, somatic and retarded activity, and interpersonal difficulties. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .82 for the scale and ranged from .57 to .88 for the subscales.

Childhood Sexual Abuse

The Childhood Sexual Abuse Scale (CSA; Finkelhor, 1994) was modified for this study. This measure contains behaviorally based items (e.g., Has anyone touched your sex organs?) rather than asking participants if they experienced sexual abuse, which allows for varying perceptions of the term “abuse”. The measure was modified to create a composite item where participants were asked to endorse seven sexual behaviors they experienced before the age of 14 with a person at least 5 years older as well as the frequency of these incidents (e.g., When you were 14 years old or younger, did an older person [at least 5 years older than you] ever fondle you in a sexual way? How many times did this occur?). Studies show that the total number of incidents correlates with greater negative outcomes (Kinzl et al., 1995), and this modified measure assesses that important component of childhood sexual abuse. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .77 for this scale.

Internalized Homophobia

The Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale (LIHS) is a 52-item questionnaire designed for lesbian women in an effort to avoid validity problems found with measures developed with gay men (Szymanski, Chung, & Balsam, 2001). The LIHS accesses five dimensions: (1) connections with the lesbian community, (2) public identification as a lesbian, (3) personal feelings about identifying as lesbian, (4) religious and moral attitudes towards lesbianism, and (5) attitudes towards other lesbians. Due to the length of the questionnaire, the personal feelings about identifying as a lesbian (PFL) subscale was used, as recommended by the author (D. M. Szymanski, personal communication, June 4, 2004). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .77 for this subscale.

Relationship Satisfaction

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976) is a 32-item instrument that assesses satisfaction, cohesion, and consensus within a relationship. The DAS is reliable and well-validated (Whisman & Jacobson, 1992). The 4 items on the DAS pertaining to sex within the relationship (categorized in the DAS as Affectional Expression) were removed from analyses of relationship satisfaction to ensure that the constructs of sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction were more independent. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .81 for the scale and ranged from .70 to .89 for the subscales. The retained subscales in the subsequent models included consensus and satisfaction.

Sexual Functioning

The Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BISF-W) is a 22-item self-report measure designed and validated to assess current levels of female sexual functioning (Mazer, Leiblum, & Rosen, 2000; Meston & Derogatis, 2002). This measure provides an overall composite score of sexual functioning as well as seven subscale scores (i.e., desire, arousal, frequency of sexual activity, receptivity/initiation, pleasure/orgasm, relationship satisfaction, and problems affecting sexual function). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .67 for the scale and ranged from .60 to .87 for the subscales.

Social Support

Social support was measured by the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ6), a 12-item measure, with half of the items assessing the quantity of social supports and half of the items assessing satisfaction with social support (Sarason, Sarason, Shearin, & Pierce, 1987). This measure is well-validated and highly correlated with the original Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .92 for this scale.

Sexual Satisfaction

The Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX; Lawrance & Byers, 1998) measures an individual’s global level of sexual satisfaction. The measure asks participants to rate their sexual relationship on five 7-point scales (i.e., good-bad, valuable-worthless, pleasant-unpleasant, positive negative, satisfying-unsatisfying). The GMSEX has been validated in married and dating relationships, as well as cross-culturally (Byers, Demmons, & Lawrance, 1998; Renaud, Byers, & Pan, 1997). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .94 for this scale.

Data Analyses

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to evaluate both proposed models. SEM is a measurement procedure that combines factor analysis and multiple regression to evaluate both the latent factors in a model as well as the measurement of the model as a whole (Kline, 1998). Additionally, SEM allows for measurement error and for the possibility of correlated residuals among indicators, which allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how factors and error terms influence one another (Schumacker & Lomax, 1996). The structural and measurement models were evaluated with the maximum likelihood estimation executed by M-Plus 3.01 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998). Multiple goodness-of-fit indices were considered. The chi-square statistic is a commonly reported indicator of fit, as it is sensitive to the assumption of multivariate normality. However, chi-square is also sensitive to sample size, which was small in this study. Therefore, other fit indices were considered. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TFI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973) provide fit indices that are less sensitive to sample size, and indicate an adequate fit for values equal to or above .90 (Klein, 1998). Additionally, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) index was referenced, with values under .08 and the lower bound of the confidence interval under .05 indicating an adequate fit (McDonald & Ho, 2002).

Results

Descriptive Data

Means and SDs for all main variables are shown in Table 2. Independent sample t-tests were conducted comparing heterosexual women and lesbian/bisexual women. Significant differences were found for many main variables (Table 2). Therefore, the two groups were not combined in any model testing.

Table 2.

Descriptive data on main study variables for heterosexual and lesbian/bisexual women in relationships

| Heterosexual (n = 139) |

Lesbian/Bisexual (n = 114) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | Range | t test |

| Social support | ||||||

| Received support | 2.83 | 1.89 | 3.06 | 2.12 | 0.00–9.00 | -.93 |

| Satisfaction with support | 5.31 | 0.96 | 5.26 | 0.94 | 0.83–6.00 | .35 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | ||||||

| Severity | 2.13 | 5.08 | 4.01 | 6.91 | 0.00–28.00 | −2.49** |

| Frequencya | 3.11 | 1.75 | 3.47 | 1.55 | 1.00–5.00 | -.94 |

| Relationship satisfaction | ||||||

| Consensus | 49.13 | 8.48 | 49.46 | 7.46 | 0.00–64.00 | -.32 |

| Cohesion | 16.16 | 4.48 | 17.26 | 3.55 | 4.00–24.00 | −2.17* |

| Satisfaction | 37.37 | 7.47 | 38.47 | 6.68 | 7.00–48.00 | −1.23 |

| Depressive symptomatology | ||||||

| Depressive affect | 4.74 | 4.45 | 4.52 | 4.40 | 0.00–21.00 | .40 |

| Positive affect | 3.83 | 3.21 | 2.92 | 2.90 | 0.00–12.00 | 2.32* |

| Somatic and retarded activity | 5.95 | 4.11 | 5.54 | 4.23 | 0.00–18.00 | .77 |

| Interpersonal problems | 0.84 | 1.15 | 0.76 | 1.04 | 0.00–6.00 | .55 |

| Sexual functioning | ||||||

| Desire | 7.30 | 2.47 | 8.44 | 2.33 | 1.29–13.00 | −3.74*** |

| Arousal | 6.99 | 2.43 | 7.98 | 2.58 | 0.50–12.00 | −3.17** |

| Frequency | 5.93 | 1.82 | 6.48 | 2.23 | 2.25–12.00 | −2.17* |

| Receptivity/initiation | 9.25 | 4.45 | 10.35 | 4.62 | 0.00–16.00 | −1.92 |

| Pleasure/orgasm | 5.16 | 2.34 | 6.17 | 2.29 | 0.00–11.25 | −3.46*** |

| Sexual problems | 5.18 | 2.44 | 4.38 | 1.93 | 0.00–11.51 | 2.83** |

| Sexual Satisfaction | 26.69 | 7.21 | 28.62 | 6.57 | 5.00–35.00 | −2.09* |

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | ||

| Children in the home | ||||||

| Yes | 70 | 50.4 | 31 | 27.2 | 14.02*** | |

| No | 69 | 49.6 | 83 | 72.8 | ||

Scores for frequency of childhood sexual abuse are as follows: 1 = one time, 2 = 2–4 times, 3 = 5–7 times, 4 = 8–10 times, 5 = 11 or more times

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001

Bivariate Analyses

In bivariate analyses, age, partner’s age, income, education, and job status were significantly correlated with several of the main study variables. Additionally, income, education, and job status were highly correlated with one another. Means of these three variables were converted to standardized z-scores and combined to form a composite socioeconomic status (SES) variable. This new SES variable also had significant correlations with main study variables; therefore, age, partner’s age, and SES were entered into the proposed model for both the lesbian and heterosexual groups.

The quantity of social support received was not significantly correlated with the other main study variables, so it was dropped from the proposed model. Satisfaction with social support remained as the indicator for social support in both models. Additionally, reported childhood sexual abuse, though significantly correlated with satisfaction with social support, r(253) = −0.26, p <.05, the CES-D activity sub-scale, r(253) = 0.21, p < .05, and the satisfaction indicator of relationship satisfaction, r(253) = -.23, p <.05, were not significantly associated with the other study variables for either the lesbian or heterosexual groups. However, given the extensive field of research suggesting that childhood sexual abuse does have negative associations with sexual and relationship functioning, it was included in model testing.

Model Evaluation

A preliminary confirmatory factor analysis indicated a poor fit for the initially proposed models that included 7 indicators of the latent factor of sexual functioning; 3 indicators of the latent factor of relationship satisfaction; and 4 indicators of the latent factor of depressive symptomatology. Modification indices indicated that only frequency of sexual activity and pleasure from sexual activity contributed significantly to the factor of sexual functioning. Similarly, the interpersonal component of depressive symptomatology contributed very little to the depressive symptoms factor. Satisfaction and consensus, subscales of the DAS, remained strong indicators for relationship satisfaction, while cohesion contributed very little. These results were found for both models, and insignificant indicators were dropped from the model in subsequent analyses.

The models adjusted for factor indicators were tested with SEM using M-Plus software, identical except for the addition of internalized homophobia in the lesbian/bisexual model. With both models, fit indices showed that even with modified factors, childhood sexual abuse became an insignificant predictor within the model. Also in both models, age and partner’s age were no longer significant factors in predicting sexual satisfaction. For both groups, these factors were dropped from the model to see if the modified model better fit the data.

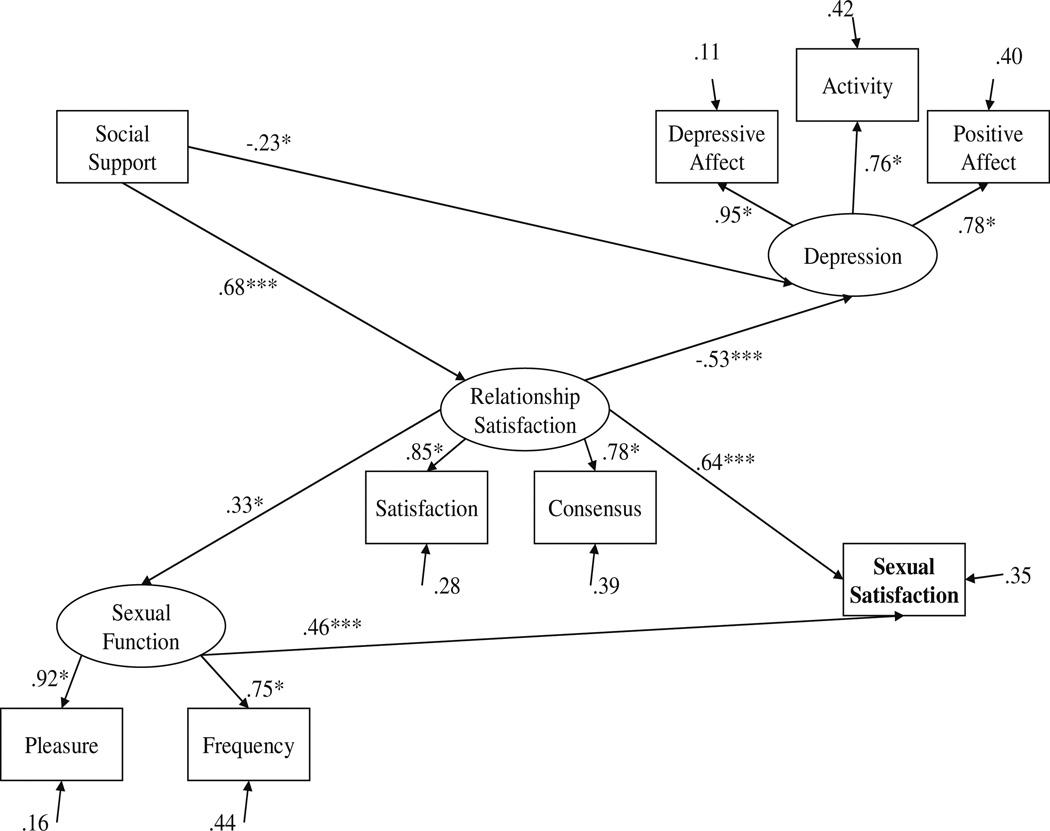

For heterosexual women, after removing age, partner’s age and childhood sexual abuse, SES dropped out of the model as a significant predictor. Removing SES, the newly modified model fit the data well (see Fig. 2): χ2 = 37.45 (23, 139). RMSEA was within range (0.07 [0.02,0.11]), and both the CFI (0.97) and the TFI (0.95) were well above the benchmark criterion of 0.90. As shown, social support (an exosystem variable) predicted relationship satisfaction (a mesosystem factor), though not sexual functioning, the other mesosystem variable. Previous findings have been replicated: the positive relationships between sexual satisfaction and both sexual functioning and relationship satisfaction. Depressive symptomatology and sexual satisfaction were initially significantly correlated, though when combined with other factors in the model, the significance between the variables drops, and there remains no direct path between the two microsystem variables. Relationship satisfaction served to mediate the association between social support and sexual satisfaction. Social support and sexual satisfaction were initially correlated, r(139) = .35, p < .001, but the addition of relationship satisfaction resulted in the correlation between social support and sexual satisfaction becoming non-significant. Squared multiple correlates indicate that the model accounts for 65% of the variance in sexual satisfaction among heterosexual women.

Fig. 2.

Ecological model of sexual satisfaction in heterosexual women (n = 139)

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

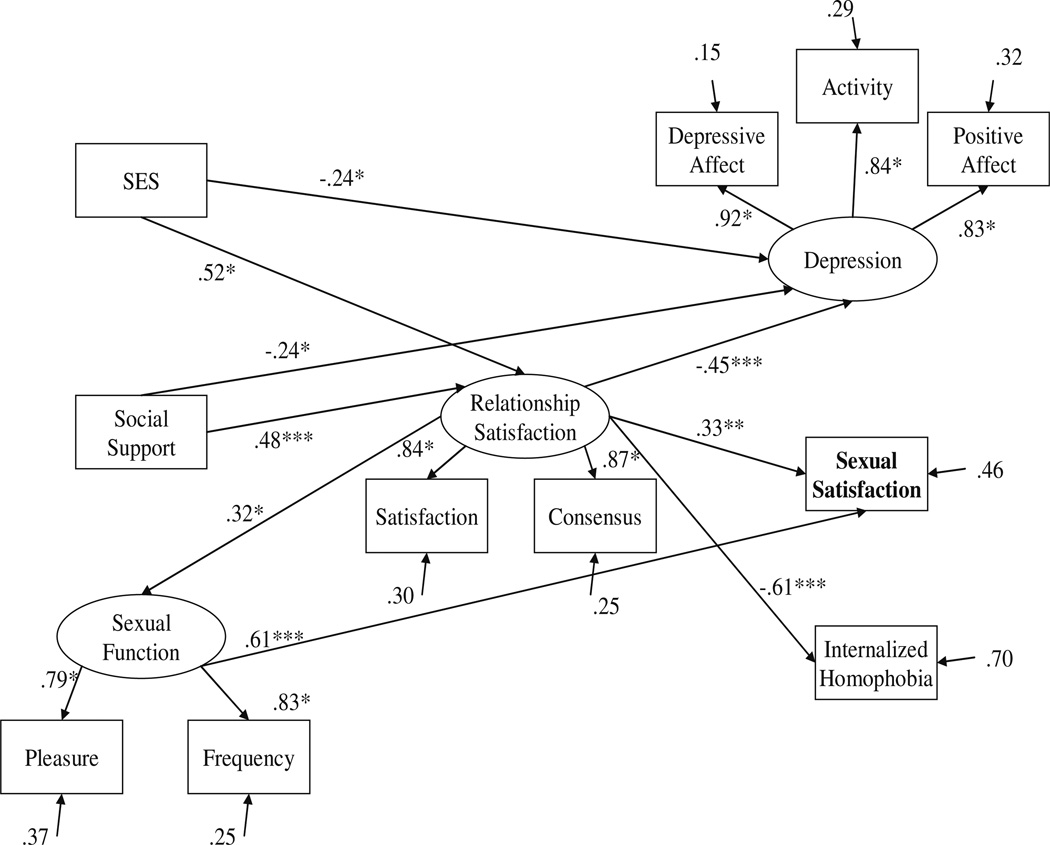

A modified model (removing age, partner’s age, and childhood sexual abuse) was also tested with the lesbian/bisexual sample (see Fig. 3). This model provided a good fit for the data, χ2 = 42.61 (27, 114). RMSEA was within range (0.077 [0.03,0.12]), and both the CFI (0.97) and the TFI (0.94) were greater than required. Similar to the heterosexual model, relationship satisfaction appeared to mediate the relationship between social support and sexual satisfaction, as well as between social support and internalized homophobia. Unlike the heterosexual model, SES remained a significant predictor within the model. Bivariate analyses indicated that internalized homophobia and sexual satisfaction were significantly correlated, r(114) = -.21, p < .05, but with all factors entered into the model, the association between the two was no longer significant. Similarly, the significant association between depressive symptomatology and sexual satisfaction in lesbian women became insignificant when other variables were entered into the model. Thus, the three microsystem variables (i.e., sexual satisfaction, depressive symptomatology and internalized homophobia) remain unconnected in the model. Squared multiple correlations indicate that this model accounts for 54% of the variance in sexual satisfaction in lesbian women.

Fig. 3.

Ecological model of sexual satisfaction in lesbian/bisexual women (n = 114)

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Comparison of the Models for Heterosexual and Lesbian/Bisexual Women

The models were tested for significant differences in the overall fit of the models as well as for differences in specific paths between factors. Internalized homophobia was removed from the lesbian/bisexual model for this comparison, as all factors included in model comparison must have responses from all participants, and only lesbian and bisexual women completed the internalized homophobia items. Thus, though SES was not a significant predictor of sexual satisfaction in the heterosexual model, it remained in the model comparison because every participant had a SES score.

Initially, the models were compared with no constraints on the paths between factors. The chi-square for this unconstrained model was 93.97, with 54 df. Then, all the paths between factors were constrained to be equal between models (e.g., the path between depressive symptomatology and relationship satisfaction was constrained to be equal in both the lesbian/bisexual model and the heterosexual model). This constrained to equivalent model had a chi-square of 112.83, df = 68. In model comparison, if the difference in chi-square surpasses the critical value given the change in degrees of freedom, the models are assumed statistically significant. Here, the change in chi-square of 18.86 was not larger than the critical value of 22.36 given a change in degrees of freedom of 13. As such, the overall models are not significantly different.

Though the models were deemed functionally equivalent, individual paths between factors were compared between models to ascertain if, though globally equivalent, there might be differences between factor relationships. Significant differences were found between sexual functioning and SES, Δχ2 = 6.17, Δdf = 1, p <.05. The paths between depressive symptomatology and SES (Δχ2 = 3.61, Δdf = 1, p <.10) and between sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction (Δχ2 = 3.50, Δdf = 1, p <.10) approached significance. When these three paths (sexual functioning and SES, depressive symptomatology and SES, and sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction) were constrained and the remaining paths free, the two models do look significantly different, Δχ2 = 13.47, Δdf = 3, p <.01. Thus, these three relationships may be considered paths that show more difference between the lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual models of sexual satisfaction.

Discussion

This study tested an ecological model of sexual satisfaction in lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual women. Microsystem variables (depressive symptoms, a history of childhood sexual abuse, and internalized homophobia), mesosystem variables (relationship satisfaction and sexual functioning), and exosystem variables (social support, presence of children in the home, and socioeconomic status) were entered into a model as predictors of sexual satisfaction. Separate models were tested for heterosexual and lesbian/bisexual women, with the model for lesbian/bisexual women including an additional factor of internalized homophobia. Individual models were evaluated for goodness-of-fit and modified to enhance fit indices when appropriate. Final models for each group (heterosexual and lesbian/bisexual) were then compared to detect significant differences between the models. Notable similarities and differences are discussed below, as well as implications for theory, clinical practice, and future research.

For both the lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual samples, the ecological model provided a good fit for the data and explained 54% and 65% of the variance in sexual satisfaction, respectively. These models predicted substantially greater variance in sexual satisfaction than other models (Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction; MacNeil & Byers, 1997). We can be certain that the ecological model assessed a wider scope of variables at different levels that influence sexual satisfaction and offers a different approach to addressing sexual satisfaction.

A factor common to both lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual models was the central role of relationship satisfaction. This connection has been well documented in previous studies and has been replicated in the present models (Bancroft, Loftus, & Long, 2003). It is notable that the association between relationship and sexual satisfaction remained robust even with the addition of other variables that also explained some of the variance in sexual satisfaction. Relationship satisfaction mediated the relationship between social support and sexual satisfaction in both lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual women. Also, relationship satisfaction mediated the association between sexual functioning and depressive symptomatology in both groups, as well as the relationship between social support and internalized homophobia in the lesbian/bisexual model.

Moreover, sexual functioning—and in particular sexual pleasure/orgasm and frequency—was another common factor that successfully predicted sexual satisfaction for both the heterosexual and lesbian/bisexual women. Interestingly, the lesbian/bisexual women scored significantly higher on all of the BISF-W subscales (i.e., desire, arousal, frequency, pleasure/orgasm; see Table 2) compared to heterosexual women. This finding may seem initially surprising given some previous work. In particular, Blumstein and Schwartz (1983) published a highly regarded study comparing lesbian, gay male, married heterosexual, and unmarried heterosexual couples. A major finding was that lesbian couples experienced less frequent sexual activity than others. Nonetheless, more recent work has begun to challenge the long-standing assumption that lesbians are not as sexual as their heterosexual counterparts. Matthews et al. (2003) found no differences in sexual frequency rates of heterosexual versus lesbian women, while Iasenza (1992) found lesbians to be more sexually arousable and more sexually assertive compared to heterosexual women. Moreover, results from another study found that lesbians reported significantly fewer sexual problems and more frequent orgasm than heterosexual women (Nichols, 2004). Our findings complement these studies, demonstrating lesbians’ increased sexual functioning with a comprehensive measure.

We had hypothesized that childhood sexual abuse would contribute to sexual satisfaction for both lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual women. Bivariate correlations indicated that childhood sexual abuse was significantly negatively correlated to social support, relationship satisfaction, and some depressive symptoms for study participants. However, when all study variables were considered in the model, the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and the main study variables became insignificant, contradicting previous research. There have been a few studies published, most notably Rind and Tromovitch (1997), which, though controversial, argue that incidence of childhood sexual abuse may not be associated with negative outcomes, or if it is, the effect is small. Possibly, the abbreviated childhood sexual abuse measure did not adequately assess the severity of the abuse in study participants. The measure did not ask about the relationship to the perpetrator (i.e., family member, stranger, etc.), nor did it address the perceived impact by the adult victim. The term “sexual abuse” encompasses a wide variety of experiences from more benign, or sex-positive experiences, to extremely traumatizing. It may be the case that the women in this study who indicated a history of behaviors that meet criteria for childhood sexual abuse experienced fewer negative consequences. Indeed, some research has suggested that the impact of child sexual abuse on adult sexual satisfaction in adults varies depending on its definition (Rellini & Meston, 2007). For example, women who actually identify as childhood sexual abuse survivors may show greater sexual distress compared to women who experienced similar unwanted sexual experiences but did not identify as childhood sexual abuse survivors (Rellini & Meston, 2007). While sexual abuse behaviors were assessed in the current study, self-identification as a childhood sexual abuse survivor was not.

Another variable that was hypothesized to contribute to sexual satisfaction was the presence of children in the home. The dichotomous variable of “children” versus “no children” failed to contribute significantly to the model. This finding is contrary to previous findings, which have supported the idea that the presence of children in the home would have negative associations with relationship satisfaction, sexual functioning, and possibly sexual satisfaction directly (Ahlborget al., 2005). We did not, however, access specific information about child-care arrangements or the age of the child, which may provide valuable information about the relationship between children in the home and other study variables.

Though SES correlated with many of the main study variables for both heterosexual and lesbian/bisexual women, it remained a significant factor only in the lesbian/bisexual model of sexual satisfaction. SES may serve as a protective factor in the face of stress, shielding an individual from a variety of negative factors. It may be the case that heterosexual women in this sample have enough institutional support (by virtue of being legally married) that SES became less important relative to other study variables. However, lesbian and bisexual relationships generally receive less institutional support, which may make women in these relationships more vulnerable to the effects of SES. Additionally, in this sample, heterosexual married women had a higher income than did lesbian women. Given that men in the United States on average make more than women, it is not surprising that a household with an adult male might have a greater annual income than one without, especially in a dual-income household (Greenstein, 2000). When income is compared across heterosexual married and lesbian cohabiting couples, lesbian couples traditionally have a significantly lower combined annual income (Kurdek, 1991), which may expose lesbian couples to additional stressors.

Finally, we had hypothesized that other microsystem variables, depressive symptomatology and internalized homophobia for lesbian/bisexual women, would predict sexual satisfaction. Bivariate correlations between the main study variables did indicate significant relationships between depressive symptomatology and sexual satisfaction for both groups, and between internalized homophobia and sexual satisfaction for the lesbian/bisexual group. However, with other study variables entered into the model, the significance of those associations fell to non-significant values. It is possible that the non-significance is due to a small sample size.

Findings from the present study have implications for theoretical conceptualizations of sexual satisfaction among women. Psychologists have documented that women are socialized to be more relationally oriented and focused. The “self-in-relation” theory offers a re-conceptualization of psychology: rather than focusing on the individual “self,” the field should focus on relationships and connections (Jordan & Surrey, 1986). This interactional sense of self does not merely value relationships but rather is inherently connected with others and tied to relationships and the context relationships create (Jordan, 1997). Thus, to assess sexual satisfaction without considering the relationships in which a woman processes her life would be to ignore an important aspect of women’s functioning.

The ecological model emphasizes the importance of relationship satisfaction in sexual satisfaction, a finding supported by “self-in-relation” theory. Sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction have been normed on a medical model with men and then extended to women. When considering sexual problems, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria are relatively medical, in the sense that they are based on asters and Johnson’s (1970) model, and may reduce sex to a physical act, a microsystem variable only, thus disregarding the myriad of non-physical factors that contribute to the quality of one’s sexual relationship, notably the relevance of the relationship itself (Tiefer, Hall, & Tarvis, 2002).

There has been some progress made in the field of sexual functioning toward this end, with feminist psychologists objecting to the traditional classification of sexual problems or concerns in women. A campaign by the Working Group for a New View of Women’s Sexual Problems (2001) highlighted that women’s sexual problems may relate not only to medical factors but also to psychological factors (e.g., the microsystem level), partner and relationships (e.g., the mesosystem level), and sociocultural, political, or economic factors (e.g., the macrosystem level). Given that there exists ample evidence that women regard sex in a more contextual framework, failing to acknowledge this framework and its implications does not adequately describe women’s sexual experiences. The ecological models derived in this study provide a theoretical framework on which to base criteria for sexual satisfaction and possibly sexual concerns, and extend female sexuality beyond physiology.

An ecological understanding of sexual satisfaction in women has distinct clinical implications aside from re-conceptualizing diagnostic criteria for female sexual concerns. Though individuals seek treatment for specific sexual problems or dysfunctions, even more couples seek counseling for less severe sexual concerns or sexual dissatisfaction (Byers, 1999). Thus, practitioners may more often deal with a lack of sexual satisfaction rather than dysfunctions that meet diagnostic criteria for a sexual disorder.

Early developments in the field of sex therapy provided individuals with sexual difficulties psychoeducation and behavioral “sensate” focused exercises (Masters & Johnson, 1970). However, as the population became more informed about sexuality and sexual practices, the direction in sex therapy shifted, and in the past two decades, sexual concerns have been approached with increasingly organic or medical treatments (Ragucci & Culhane, 2003; Rosen & Leiblum, 1995). In fact, many individuals with sexual concerns visit their primary care physician rather than a mental health professional for treatment (Ragucci & Culhane, 2003). Heiman (2002) noted that little research on the psychological treatment of sexual dysfunction has been done since the late 1980s, so complete is the paradigm shift.

This study provides support for a psychological model of sexual satisfaction, particularly for women. It may be more beneficial to intervene with a couple, not merely with the individual voicing sexual concerns. It may be that for many women sexual complaints mask underlying relationship problems. As such, treating the sexual problem without assessing and possibly treating relational concerns could lead to an ineffective intervention. Treating the couple is not a unique approach when there are sexual concerns (Schnarch, 1991), but there has been little evidence to support any theory supporting treating the coupleas opposed to the individual. This model indicates that increasing relationship satisfaction may have global changes for women, increasing sexual satisfaction as well.

Given that the models of sexual satisfaction are functionally equivalent between lesbian/bisexual women and heterosexual women, clinical implications are similar for both groups. Though there is far less published about sexual problems in lesbian or bisexual women, some evidence shows that there are common processes in couple therapy that serve to increase relationship satisfaction in both heterosexual and lesbian couples (Martell et al., 2004). Addressing relationship concerns specific to lesbian/bisexual couples (i.e., gender role socialization, oppression, and internalized homophobia) will also increase relationship satisfaction in lesbian/bisexual couples and concomitantly increase sexual satisfaction for these women (Green & Mitchell, 2002).

Several methodological factors limited this study. Participants in this study were predominantly Caucasian women of a fairly high socioeconomic status. Additionally, women were recruited in and around Seattle, Washington, a city known for its liberal leanings and gay-friendly atmosphere. Caution should be used in generalizing to both heterosexual and lesbian/bisexual women in other areas of the country. Additionally, this model may not be applicable for women of color, particularly lesbian and bisexual women of color who live with a dual minority status, as an ethnic/racial minority and as a sexual minority, which would likely create additional stressors. Also, while data collection via the Internet has been shown to be similar to other recruitment methods regarding the validity of data (Gosling, Vazire, Srivastavea, & John, 2004), it may lead to sampling of a specific group of individuals who have access to a computer and are facile with that technology. Though computers and the Internet are becoming more and more widespread, they are likely less accessible in more poverty-stricken neighborhoods or in lower paying jobs. Thus, the mode of recruitment is likely connected to the high SES sample that was recruited. Finally, all data were cross-sectional; therefore, causal effects cannot be assumed. For example, we cannot determine whether depressive symptomatology is a precursor to relationship dissatisfaction in our sample or whether relationship dissatisfaction itself leads to depressive symptomatology.

Despite these limitations, the study contributes to the current literature and points to several directions for future research. An unexpected opportunity was presented when 14 bisexual women completed the study, despite inclusion criteria of identifying as either lesbian or heterosexual. Research on bisexual women and men remains scarce, and often individuals who identify as bisexual are grouped with gay men or lesbian women without testing for group differences (Cochran, Sullivan, Greer, & Mays, 2003). Some studies note that bisexual men and women do have experiences that are different from gay and lesbian individuals, sometimes experiencing hostility expressed at their bisexual orientation (Herek, 2002). Additionally, bisexual women may feel ostracized by both heterosexual and lesbian women for occupying an uncomfortable “middle ground,” not adhering to a dichotomous understanding of sexual orientation (Weasel, 1996). The concept of sexual plasticity in women (Baumeister, 2000) may unintentionally serve to support a belief that women who identify as bisexual are in flux, and in transition from identifying as heterosexual to lesbian or vice versa. As such, bisexual women, possibly even more than bisexual men, may have the credulity of their sexual orientation questioned by others. In this study there were no significant differences between lesbian and bisexual women with female partners in any sociodemo-graphic or main study variables, so the two groups were combined. Nonetheless, future studies should examine variables that may distinguish bisexual women from lesbian and heterosexual women and contribute to their sexual satisfaction.

Though the models of sexual satisfaction for heterosexual and lesbian/bisexual women were functionally equivalent, there are components within the models that differ. Given the nature of our sample, we could not determine whether those differences were due to participant sexual orientation or sex of partner. In this study, bisexual women with female partners were not significantly different from lesbian women. However, it is not possible to explain this similarity with certainty. It could be that lesbian and bisexual women are socialized in a similar manner around their sexual orientation or it could be because they both have female partners. Both theory and research provide evidence for either argument. This study highlights the relevance of the relationship in perceptions of sexual satisfaction. It may be that women are so relationally oriented that they adapt themselves to the specific conditions of their relationship and partner, including the sex of their partner.

One possible means of addressing this conundrum is to recruit more bisexual women, creating a sample of bisexual women with male partners and a sample of bisexual women with female partners. With these two groups, sexual orientation remains constant (bisexual) and gender of partner varies, so differences between models could be more easily attributed to gender of partner. However, this line of research has its own limitations, particularly knowing that sexual orientation is more mutable in women. Additionally, bisexual women with male partners may “pass” as heterosexual, and may experience less discrimination or victimization on the basis of their sexual orientation relative to a bisexual woman with a female partner. Though future studies would need to address these limitations, sampling bisexual women may provide the field greater clarity about differences between women of diverse sexual orientations.

The ecological model contains a macrosystem level, which includes the broadest factors that influence a system, generally culture, societal beliefs and norms, and laws. Future studies that recruit a more diverse population will have the opportunity to find variance at the macrosystem level (i.e., political climate and gay marriage rights). Then, a more expanded model of sexual satisfaction might be evaluated, one that perhaps could comprehensively elucidate the complex interconnections of factors that underlie sexual satisfaction among women.

References

- Ahlborg T, Dahlof LG, Hallberg LR. Quality of intimate and sexual relationship in first-time parents six months after delivery. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42:167–174. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala J, Coleman H. Predictors of depression among lesbian women. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2000;4:71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JM, Gaulin S, Agyei Y, Gladue BA. Effects of gender and sexual orientation on evolutionarily relevant aspects of human mating psychology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:1081–1093. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DS. Depression and sexual dysfunction. British Medical Bulletin. 2001;57:81–99. doi: 10.1093/bmb/57.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballou M, Matsumoto A, Wagner M. Toward a feminist ecological theory of human nature: Theory building in response to real-world dynamics. In: Ballou M, Brown LS, editors. Rethinking mental health and disorder: Feminist perspectives. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 99–144. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam K. Lesbian internalized homophobia, relationship quality, and domestic violence. Chicago, IL: Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; Aug, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J, Loftus JL, Long SJ. Distress about sex: A national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:193–208. doi: 10.1023/a:1023420431760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:347–374. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein P, Schwartz P. American couples: Money, work and sex. New York: Pocket Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The International encyclopedia of education. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Oxford, England: Elsevier; 1994. Ecological models of human development; pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Byers SE. The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction: Implications for sex therapy with couples. Canadian Journal of Counseling. 1999;33:95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Byers SE. Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42:113–118. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers SE, Demmons S, Lawrance K. Sexual satisfaction within dating relationships: A test of the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15:257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher FS, Sprecher S. Sexuality in marriage, dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:999–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Clark WM, Serovich JM. Twenty years and still in the dark? Content analysis of articles pertaining to gay, lesbian and bisexual issues in marriage and family therapy journals. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1997;23:239–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1997.tb01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AH. Recognition and assessment of sexual dysfunction associated with depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Sullivan J, Mays VM. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:53–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer D. Emotional support, conflict, depression and relationship satisfaction in a romantic partner. Journal of Psychology. 2004;138:532–543. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.138.6.532-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE. Social support in couples: Marriage as a resource in times of stress. London: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Cherry C, Houch P, Kupfer DJ. Prospective assessment of sexual function in women treated for recurrent major depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;38:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Katz J, Jackson JL. Sexual desire discrepancies: Effects on sexual and relationship satisfaction in heterosexual dating couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1999;28:553–567. doi: 10.1023/a:1018721417683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D. Interpersonal functioning among women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse: Empirical findings and methodological issues. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:553–576. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy SM, Rusbult CE. Satisfaction and commitment in homosexual and heterosexual relationships. Journal of Homosexuality. 1985;12:1–23. doi: 10.1300/j082v12n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JM. The effects of antidepressants on sexual functioning in depressed patients: A review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:22–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1994;18:409–417. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorcey M, Santiago JM, McCall-Perez F. Psychological consequences for women sexually abused in childhood. Social Psychiatry. 1986;54:129–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00582682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Vazire S, Srivastava S, John OP. Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about Internet questionnaires. American Psychologist. 2004;59:93–104. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Levenson RW, Gross J, Frederickson BL, McCoy K, Rosenthal L, et al. Correlates of gay and lesbian couples’ relationship satisfaction and relationship dissolution. Journal of Homosexuality. 2003;45:23–43. doi: 10.1300/J082v45n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R, Mitchell V. Gay and lesbian couples in therapy: Homophobia, relational ambiguity and social support. In: Gurman AS, Jacobson NS, editors. Clinical handbook of couple therapy. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford; 2002. pp. 546–568. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein T. Economic dependence, gender, and the division of labor in the home: A replication and extension. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hare J. Concerns and issues faced by families headed by a lesbian couple. Families in Society. 1994;75:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Heiman JR. Psychologic treatments for female sexual dysfunction: Are they effective and do we need them? Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2002;31:445–450. doi: 10.1023/a:1019848310142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39:264–274. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Johnson T, Wilsnack SC. Sexual assault and alcohol abuse: A comparison of lesbians and heterosexual women. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:515–532. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston M, Schwartz P. The relationships of lesbians and gay men. In: Woods JT, Duck S, editors. Under-studied relationships: Off the beaten track. London: Sage; 1995. pp. 89–121. [Google Scholar]

- Iasenza S. The relations among selected aspects of sexual orientation and sexual functioning in females. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1992;52:3945. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan J. A relational perspective for understanding women’s development. In: Jordan J, editor. Women’s growth in diversity: More writings from the Stone Center. New York: Guilford; 1997. pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KM, Deluty RH. Social support, coming out, and relationship satisfaction in lesbian couples. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2000;4:145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan J, Surrey J. The self-in-relation: Empathy and the mother-daughter relationship. In: Bernay T, Cantor D, editors. The psychology of today’s woman: New psychoanalytic visions. Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press; 1986. pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Julien D, Chartrand E, Simard M, Bouthillier D, Begin J. Conflict, social support, and relationship quality: An observational study of heterosexual, gay male, and lesbian couples’ communication. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:419–428. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen TJ, Junginger J. Correlates of lesbian sexual functioning. Journal of Women’s Health. 2007;16:499–509. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzl JF, Trawefer C, Biebl W. Sexual dysfunctions: Relationship to childhood sexual abuse and early family experiences in a nonclinical sample. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1995;19:785–792. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00048-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Sex role self-schema and psychological adjustment in coupled homosexual and heterosexual men and women. Sex Roles. 1987;17:549–562. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Relationship quality in gay and lesbian cohabiting couples: A 1-year follow-up study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1989;6:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Correlates of relationship satisfaction in cohabiting gay and lesbian couples: Integration of contextual, investment, and problem-solving models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:910–922. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.6.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. The nature and correlates of relationship quality in gay, lesbian and heterosexual cohabitating couples: A test of the individual difference, interdependence, and discrepancy models. In: Greene BG, Herek GM, editors. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay issues: Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance K, Byers ES. Interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction questionnaire. In: Davis C, Yarber WL, Bauserman R, Schreer G, Davis SL, editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 514–518. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard LM, Follette VM. Sexual functioning in women reporting a history of child sexual abuse: Review of the empirical literature and clinical implications. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2002;13:346–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb TB, Williams JK, Carmona JV, Rivkin I, Wyatt GE, Chin D, et al. Child sexual abuse: Associations with the sexual functioning of adolescents and adults. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2002;13:307–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey RA, Diemer MA, O’Brien BA. Psychological intimacy in the lasting relationships of heterosexual and same-gender couples. Sex Roles. 2000;42:201–227. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil S, Byers ES. The relationship between sexual problems, communication, and sexual satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 1997;6:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR, Safren SA, Prince SE. Cognitive behavioral therapies with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual inadequacy. New York: Bantam Books; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Tartaro J, Hughes TL. A comparative study of lesbian and heterosexual women in committed relationships. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7:101–114. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazer NA, Leiblum SR, Rosen RC. The Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BSIF-W): A new scoring algorithm and comparison of normative and surgically meno-pausal populations. Menopause. 2000;7:350–363. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho MR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Derogatis LR. Validated instruments for assessing female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2002;28:155–164. doi: 10.1080/00926230252851276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BC. Lesbian couples and their parents: The effects of perceived parental attitudes on the couple. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1989;68:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Dunne MP, Purdie DM, Boyle FM, Coxeter PD. Sexual abuse in childhood and sexual dysfunction in adulthood: An Australian population-based study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2005;34:517–526. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-6277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M. Lesbian sexuality/female sexuality: Rethinking ‘lesbian bed death’. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2004;19:363–371. [Google Scholar]

- Oetjen H, Rothblum ED. When lesbians aren’t gay Factors affecting depression among lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality. 2000;39:49–73. doi: 10.1300/J082v39n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA. Lesbian and gay relationships. In: Garnets LD, Kimmel DC, editors. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay males experiences. New York: Columbia University Press; 1991. pp. 395–419. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, Padesky C, Hamilton M. Satisfaction in lesbian relationships. Journal of Homosexuality. 1982;8:23–35. doi: 10.1300/j082v08n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillari V, Newsom M. Human behavior inthe social environment: Families, groups, organizations, and communities. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ragucci KR, Culhane NS. Treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2003;37:546–555. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellini A, Meston C. Sexual function and satisfaction in adults based on the definition of child sexual abuse. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2007;4:1312–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud CA, Byers ES, Pan S. Sexual and relationship satisfaction in mainland China. Journal of Sex Research. 1997;34:399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Rind B, Tromovitch P. A meta-analytic review of findings from national samples on psychological correlates of child sexual abuse. Journal of Sex Research. 1997;34:237–255. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Treatment of sexual disorders in the 1990s: An integrated approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:877–890. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rosser BRS. Psychodynamics and psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996;52:15–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199601)52:1<15::AID-JCLP2>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1987;4:497–510. [Google Scholar]