Abstract

Background

Asymmetries in dynamic balance stability have been previously observed. The goal of this study was to determine whether leg preference influenced the stepping response to a waist-pull perturbation in older adult fallers and non-fallers.

Methods

39 healthy, community-dwelling, older adult (>65 years) volunteers participated. Participants were grouped into non-faller and faller cohorts based on fall history in the 12 months prior to the study. Participants received 60 lateral waist-pull perturbations of varying magnitude towards their preferred and non-preferred sides during quiet standing. Outcome measures included balance tolerance limit, number of recovery steps taken and type of recovery step taken for perturbations to each side.

Findings

No significant differences in balance tolerance limit (P ≥ 0.102) or number of recovery steps taken (η2partial ≤ 0.027; P ≥ 0.442) were observed between perturbations towards the preferred and non-preferred legs. However, non-faller participants more frequently responded with a medial step when pulled towards their non-preferred side and cross-over steps when pulled towards their preferred side (P = 0.015).

Interpretation

Leg preference may influence the protective stepping response to standing balance perturbations in older adults at risk for falls, particularly with the type of recovery responses used. Such asymmetries in balance stability recovery may represent a contributing factor for falls among older individuals and should be considered for rehabilitation interventions aimed at improving balance stability and reducing fall risk.

Keywords: Falls, Stepping response, Leg preference, Older adults

1. Introduction

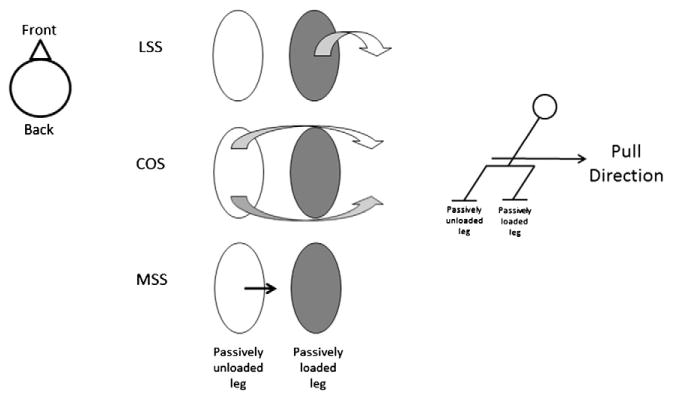

Aging effects on lateral balance are apparent. Laterally-directed falls, which result in landing impact near the hip, increase the risk of hip fracture (Hayes et al., 1993). Older adults tend to be less efficient in recovering from standing balance perturbations and to select less effective stepping strategies in response to lateral challenges to standing balance (Mille et al., 2005). Decreased ability to control lateral balance or to respond to lateral perturbations to balance stability effectively, in turn, increases risk of falling (Hilliard et al., 2008). Stepping responses to lateral standing balance perturbations are well-characterized. Three recovery stepping strategies are commonly observed (Maki et al., 2000; Mille et al., 2005; Yungher et al., 2012): 1) a lateral side step with the passively loaded leg; 2) an unloaded crossover step with the passively unloaded leg in front of or behind the body; and 3) an unloaded step with the passively unloaded leg that moves medially towards the passively loaded leg followed by a lateral step with the passively loaded leg (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Step type definitions for lateral side step (LSS), crossover steps (COS) and a medial side step (MSS). During a COS, the stepping limb can either cross in front of or behind the stance limb.

Older adults use multiple step recoveries more than younger adults (Patton et al., 2006). Older adult fallers also begin taking steps at lower perturbation magnitudes (Patton et al., 2006) and have a lower “balance tolerance limit” (BTL, limit at which multiple step rather than single step recovery strategies are used) than older adult non-fallers (Yungher et al., 2012). Younger adults often use lateral side-stepping strategies when exposed to lateral waist-pull perturbations whereas older adults tend to use crossover stepping response strategies (Mille et al., 2005, 2013). These studies have mostly focused on responses to perturbations in one direction only (Patton et al., 2006) or grouped outcomes from perturbations to the left and right together (Mille et al., 2005; Yungher et al., 2012); they have not yet examined whether stepping responses are dependent on the perturbation direction with respect to leg preference.

Asymmetries in dynamic balance stability have been observed using various mechanical (McAndrew Young et al., 2012; Rosenblatt and Grabiner, 2010) and nonlinear measures of stability (Granata and Lockhart, 2008). However, these stability asymmetries have not always been statistically significant and their clinical significance remains unknown. One previous study indicates that asymmetries in dynamic stability may be associated with fall-risk status in older adults (Granata and Lockhart, 2008). As such, asymmetries in dynamic stability may represent a previously unrecognized precipitating factor for falls in older adults.

Leg preference has been indicated as a potential contributing factor to balance asymmetries (Rosenblatt and Grabiner, 2010). The “preferred” or “dominant” leg depends on the activity. Peters (Peters, 1988) suggested that the preferred leg is the leading or “manipulating” leg and the non-preferred leg is the support leg. In a one-leg standing balance or ball-kick test, the leg on which an individual stands is the non-preferred leg and the lifted or kicking leg is the preferred or dominant leg. Previous work indicates that leg dominance, where dominance was defined as the kicking leg, does not appear to influence unperturbed single-leg standing postural balance of young adults (Alonso et al., 2011). However, no studies have investigated this relationship in older adults. Moreover, marked asymmetries in minimum toe clearance, an indicator of potential to fall, between the dominant and non-dominant limbs during walking in older adults at high-risk for falls have been observed (Nagano et al., 2011).

We wanted to determine how leg preference affected balance recovery strategies in older adults with and without a history of falling following a perturbation to standing balance. We defined the preferred/non-preferred leg based on the suggestion of Peters (Peters, 1988) using a one-leg balance test and administered lateral standing balance perturbations at the waist in the directions of participants' preferred and non-preferred legs. We reasoned that participants' balance would be more challenged when individuals were perturbed towards their non-preferred, or stabilizing, leg because the stabilizing leg was also the less dexterous leg and as such less likely to be used to quickly respond to the balance perturbation. We hypothesized that older individuals, regardless of fall status would (1) be more likely to take multiple, riskier recovery steps at a lower perturbation magnitude (i.e. have a lower BTL), (2) require more recovery steps and (3) utilize less biomechanically favorable stepping strategies (i.e. use more crossover steps) when perturbed towards their non-preferred (i.e. support) side. We further hypothesized that older adults with and without history of falling would exhibit systematic differences in the numbers of steps and stepping strategy utilized to recover their standing balance. Specifically, we predicted that older adults with a history of falling would take more steps and use crossover stepping strategies more frequently than older adult non-fallers when pulled towards their non-preferred, or stabilizing, leg.

2. Methods

Thirty-nine healthy, community dwelling older adult volunteers participated (20 males/19 females, 65–87 years old). Potential participants underwent a telephone screen and medical examination. Exclusion criteria included: 1) cognitive impairment (Folstein Mini Mental Score <24); 2) sedative use; 3) non-ambulatory; 4) any clinically significant functional impairment related to musculoskeletal, neurological, cardiopulmonary, metabolic or other general medical problems; 5) participated in any regular vigorous or muscle strengthening exercise regimen; and 6) Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Survey score >16. All participants provided written, informed consent prior to participation, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the Baltimore Veteran's Administration Medical Center.

Participants were grouped into faller and non-faller cohorts based on fall history in the 12 months prior to the study (Lord et al., 1999). A fall was defined as “coming to rest unintentionally on the ground or lower level, not as a result of a major intrinsic event (such as stroke) or overwhelming hazard” (Tinetti et al., 1988). Any individual who fell 1 or more times in the past year was classified as a faller.

The experimental setup has been previously presented (Yungher et al., 2012). Briefly, participants received 60 lateral waist-pull perturbations of varying magnitude during quiet standing using a custom stepper motor waist-pull system for inducing protective stepping (Pidcoe and Rogers, 1998). Participants wore a belt around their waist to which cables for the waist-pull system were attached and through which the perturbations were applied. The application point of the perturbation was standardized for different body types by aligning the pulling cables with the same anatomical landmarks (pelvis markers) for each subject. Six trials were conducted for each of 5 different pull intensities to the left and to the right (2 directions × 5 intensities × 6 repetitions). The smallest pull magnitude (Level 1) caused a displacement of 4.5 cm at 8.6 cm/s. The largest pull magnitude (Level 5) caused a displacement of 22.5 cm at 50 cm/s. The order in which the trials were presented was randomized to prevent anticipatory and sequence learning effects.

Participants stood in a self-selected, comfortable standing position at the start of each trial with each foot on a separate force platform (Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA). Foot tracings, of the self-selected foot placement, ensured consistent foot placement between trials. They were instructed to “relax and react naturally to prevent themselves from falling.” Kinetic data were collected at 600 Hz. Kinematic data were collected using a 6-camera motion analysis system (Vicon, Centennial, CO, USA) at 120 Hz. Reflective markers were placed bilaterally on the following anatomical landmarks: mastoid process, acromion process, lateral elbow joint, radial and ulnar prominences of wrist, anterior and posterior superior iliac spine, greater trochanter, lateral knee and lateral malleolus. A single marker was also placed in the center of the forehead. Wand markers were attached bilaterally to the upper arm, thigh and lower leg.

Numbers and types of steps were documented by observation and kinematic data. Step count was the number of steps taken to recovery balance in each trial and was averaged over all of the trials for each perturbation-direction combination. Three stepping strategies were observed as mentioned earlier (Yungher et al., 2012): 1) a lateral side step with the passively loaded leg (LSS); 2) an unloaded crossover step with the passively unloaded leg in front of or behind the body (COS); and 3) an unloaded step with the passively unloaded leg that moves medially towards the passively loaded leg (MSS) (Fig. 1). For each trial, step type were recorded for the first step only. If no recovery steps were taken, the trial was recorded as a no step (NOS)trial and NOS trials were included in the analysis of step response types.

Leg preference was determined by recording the leg participants chose to stand on when asked to balance on one leg for 10 s. The leg lifted was considered the preferred, or dexterous, leg and the leg on which participants stood was the non-preferred, or support, leg.

The balance tolerance limit (BTL) is the perturbation magnitude at which an individual takes more than one step on average to recover his or her balance following the perturbation (Yungher et al., 2012). The BTL was calculated for each subject for pulls to the preferred and non-preferred sides.

T-tests were used to assess differences between fall group characteristics. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to analyze side-to-side differences in BTL for combined data and for faller and non-faller groups separately. Step count and step type results were grouped by magnitude category: Below, At and Above BTL. A three-way mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) (fall history × leg preference direction × magnitude) was used to assess statistical differences in step count. Pearson chi-square analysis was used to determine the interaction between step type and leg preference direction at each magnitude for all subjects (i.e. how frequently a given step type was used for pulls in a given direction at a given magnitude) and between first step type and leg preference direction for each fall-status group. Pearson chi-square analysis was also used to determine the interaction between type of COS step (cross-front vs. cross-back) and leg preference direction at each magnitude for each fall-status group. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistics were conducted using SPSS 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

There were no significant differences between faller and non-faller participant characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by group.

| Fallers | Non-fallers | |

|---|---|---|

| # participants | 16 | 23 |

| Age | 73.4 ± 1.1 | 74.6 ± 1.6 |

| Height (cm) | 167.1 ± 2.8 | 168.1 ± 2.0 |

| Weight (kg) | 79.8 ± 4.8 | 78.1 ± 3.0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 1.2 | 27.4 ± 0.8 |

| Activity-specific balance confidence score (max. 100%) | 90.7 ± 2.4 | 94.5 ± 1.0 |

| Berg balance scale (max. 56) | 53 ± 0.8 | 54 ± 0.4 |

| Dynamic gait index (max. 24) | 19.5 ± 0.8 | 21.2 ± 0.4 |

Note: no significant differences were found between groups.

3.2. Balance tolerance limit (BTL)

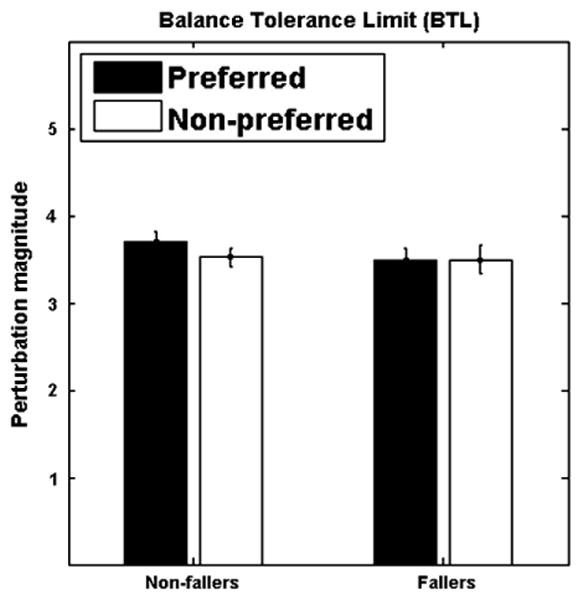

The BTL was not significantly different for pulls to the preferred versus non-preferred sides for all participants combined (P = 0.206) or for the faller and non-faller groups independently (P ≥ 0.102; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Balance tolerance limit (BTL) for perturbations towards the preferred and non-preferred sides by fall-risk status. For most subjects, BTL was at perturbation magnitude of 3 or 4, resulting in the observed mean BTL of ∼3.5. Perturbation magnitudes caused displacements ranging from 4.5 cm at Level 1 to 22.5 cm at Level 5. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

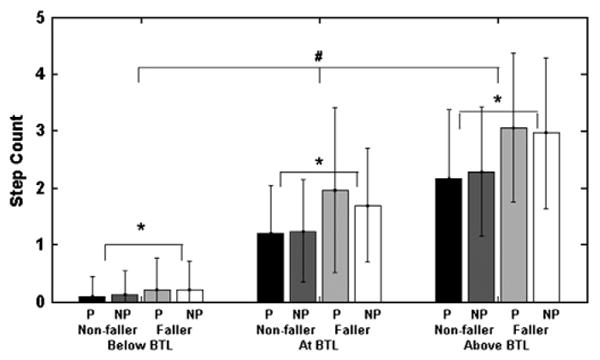

3.3. Recovery step count

Mauchley's test of sphericity indicated that sphericity could be assumed for magnitude (P = 0.060) and direction × magnitude (P = 0.094). There was a significant Within-Subjects main effect for magnitude (η2partial = 0.874; P ≤ 0.0005), with participants taking more steps with increasing perturbation magnitude, but no significant Within-Subject, main, 2-way or 3-way interactions involving direction (η2partial ≤ 0.027; P ≥ 0.442). There was a significant Between-Subject main effect of fall history for recovery step count with the faller group taking more steps than the non-faller group across magnitude (η2partial = 0.169; P = 0.019; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean number of recovery steps taken for pulls to preferred (P) and non-preferred (NP) sides. # indicates P < 0.05 for with-in subject effect of magnitude. * indicates P < 0.05 for Between-Subject effect of fall-status. No significant effect of pull direction was observed.

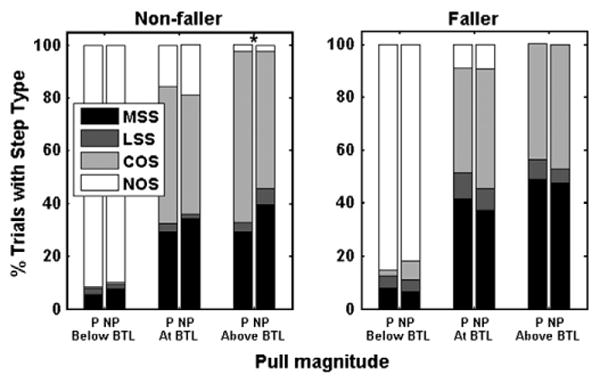

3.4. Frequency of recovery step type

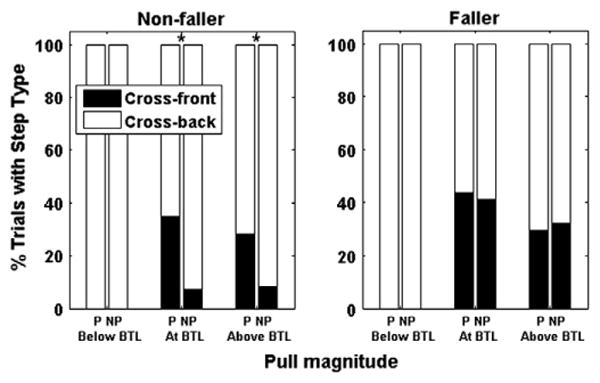

Collectively, there was not a significant interaction between direction and response first step type at any perturbation magnitude for the older adult population in this study (P ≥ 0.325; Fig. 4). However, when we examined the results by fall history, non-fallers did exhibit significant first step type by direction interactions (P = 0.008). Specifically, these differences occurred when pull magnitudes were Above their BTL. Above their BTL, non-fallers had an increased frequency of MSS first steps when pulled towards their non-preferred, or stabilizing, side and more frequently, used COS stepping strategies when pulled towards their preferred, or dexterous, side (P = 0.015). The faller group exhibited no significant first step type frequency by direction interactions overall (P = 0.549) or at any specific magnitude (P ≥ 0.332); however, Above their BTL, the trends in step type were opposite those of non-fallers. Significant trends were not found at magnitudes Below the BTL for either fall group, which may have been because during this condition participants rarely needed to take recovery steps to respond to the perturbation. Table 2 contains counts of the number of trials in which the various step types were used.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of trials in which a given recovery first step type was taken for pulls towards the preferred (P) and nonpreferred (NP) sides for pull magnitude category. Recovery first step types included medial step (MSS), lateral side step (LSS), crossover step (COS) or no step (NOS). * indicate significant interaction between step type and pull direction for a pull magnitude category at the P < 0.05-level.

Table 2.

Number of trials in which lateral (LSS), crossover (COS), medial (MSS) and no (NOS) recovery steps were taken for perturbations towards the preferred and non-preferred legs for perturbation magnitudes Above, At and Below the balance tolerance limit.

| LSS | COS | MSS | NOS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Magnitude | Fall status | Non-preferred | Preferred | Non-preferred | Preferred | Non-preferred | Preferred | Non-preferred | Preferred |

| Above | Faller | 116 | 102 | 89 | 111 | 15 | 10 | 3 | 0 |

| Non-faller | 91 | 111 | 189 | 167 | 11 | 18 | 13 | 12 | |

| At | Faller | 26 | 33 | 34 | 41 | 12 | 6 | 20 | 15 |

| Non-faller | 37 | 41 | 61 | 52 | 4 | 2 | 35 | 33 | |

| Below | Faller | 10 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 89 | 103 |

| Non-faller | 9 | 19 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 177 | 165 | |

Because COS were a significant percentage of the first step type taken, we examined the distribution of cross-over step types (cross-front and cross-back) with respect to the total number of trials in which a COS was used as the first step type for a given direction, magnitude and fall group. Significant differences in the frequency of cross-front and cross-back step types in response to perturbations towards the preferred vs. non-preferred sides were observed for non-fallers At and Above their BTL (P < 0.0005; Fig. 5). There were less cross-over steps taken from perturbations to the non-preferred side relative to the preferred side. Fallers demonstrated no significant interactions between crossover step type and leg preference direction at any perturbation magnitude (P ≥ 0.684).

Fig. 5.

Cross-front or cross-back step distribution as a percentage of the total number of trials with crossover steps (COS) for the first step for perturbations towards the preferred (P) and non-preferred (NP) sides. * indicate significant interaction between step type and direction for a pull magnitude category at the P < 0.05-level.

4. Discussion

We examined the relationship between leg preference and standing balance recovery in older adults. Regardless of previous history of falls, we did not find significant differences between the perturbation magnitudes at which participants required more than one step to recover their standing balance (i.e. no significant difference in BTL on the preferred and non-preferred sides). While individuals with history of falls took more recovery steps than non-fallers for pulls in both directions, neither group took more recovery steps when pulled towards one side versus the other. However, non-fallers took more crossover steps when pulled towards their preferred, or dexterous, side and used a MSS recovery approach more frequently when pulled towards their non-preferred, or stabilizing, side. Fallers demonstrated no significant differences in recovery step type, with respect to leg preference, regardless of perturbation magnitude.

We predicted that individuals would have a lower BTL when pulled towards their non-preferred side. We reasoned that when pulled towards the stabilizing (i.e. less dexterous) side an individual would be less able to appropriately position their leg for optimal recovery and that the individual would therefore require more steps to recover at a smaller perturbation magnitude. Our results did not support this hypothesis as there were no significant differences in BTL between sides collectively, or for either fall group (Fig. 2).

All participants took more steps, on average, as the magnitude of postural perturbations applied increased (Fig. 3). An increase in number of recovery steps in response to an increasingly large perturbation is consistent with previous studies (Luchies et al., 1994). However, we had predicted that differences would be observed between the numbers of recovery steps taken when the pull was towards the preferred versus the non-preferred leg, specifically that more steps would be taken when pulled towards the non-preferred, or stabilizing, leg. This hypothesis was also not supported by our data as participants were able to respond equivalently, in terms of number of steps required to regain their balance, regardless of perturbation direction. That one leg may be preferred for dexterity or stabilizing tasks did not seem to influence the total number of steps needed to recover.

Although the number of recovery steps did not diverge based on leg preference Above individuals' BTL, stepping strategies did for the non-fallers. This group tended to use MSS strategies when pulled towards their non-preferred, or stabilizing, side and a crossover step strategy more frequently when pulled to their preferred, or dexterous, side (Fig. 4). Individuals with history of falls, however, did not display these trends. Below, we examine these trends by step type in order to explain how they are related to leg preference.

Initiating a balance perturbation recovery with a lateral step is the most biomechanically efficient approach. An individual's base of support is quickly enlarged upon step touchdown, ideally “capturing” the center of mass within it. There is no opportunity for limb collision. Not surprisingly, then, young adults take more lateral recovery steps in response to lateral standing balance perturbations (Mille et al., 2005); however older adults tend to utilize other step types. Consistent with these earlier findings, lateral steps constituted <2% of first recovery steps taken by the non-fallers Above their BTL (Fig. 4). When taking a lateral step in response to a perturbation towards the non-preferred side, individuals step with their non-preferred leg. It is important to remember, however, that the non-preferred leg, as defined here, is an individual's supporting or stabilizing leg during a one-leg standing task. Thus, a lateral step required them to step with the leg they would normally choose to stand on for a standing balance task rather than to step with the leg they would prefer to lift and move to maintain balance. This indicates that individuals are “comfortable” using their non-support leg as an anchor while re-positioning their preferred support leg.

A similar response as the lateral step is the MSS as it consists of a medial step on one side and is generally followed by the lateral repositioning step on the other side. For non-fallers, the frequency of MSS first step responses increased for pulls towards the non-preferred side (Fig. 4). Non-fallers were using this strategy as a first recovery step response to ∼40% of the perturbations towards their non-preferred, or stabilizing, side compared to only ∼30% of the time when perturbed toward their preferred side at magnitudes Above their BTL. Thus, the non-fallers did indicate a preference to move their preferred dexterous leg over their non-preferred support leg as an initial response to a perturbation Above their BTL. However, given the relatively small displacement amplitude of the initial medial step, and the larger excursion of the following lateral step with the opposite limb, it is apparent that the second step laterally is the more stabilizing component of the MSS sequence. Therefore, non-fallers showed an adaptive response pattern during imbalance towards their preferred stabilizing limb that moderated their tendency to use potentially more destabilizing and riskier crossover steps for this direction.

The tendency of older adults to take more COS than LSS, as we observed in both directions for both groups At and Above the BTL (Fig. 4), is consistent with previous observations indicating that older adults tend to take more COS than LSS (Mille et al., 2005). Non-fallers took crossover recovery steps more frequently when pulled towards their preferred side, where individuals are stepping with their non-preferred leg. During crossover stepping, there are two options. One can cross the landing leg in front of the stance leg (“cross-front” step) or behind it (“cross-back” step). In general, the frequency of cross-back steps used increased with increasing magnitude regardless of fall-status or pull direction (Fig. 5). In taking a cross-back step, an individual cannot see the surface on which their step lands, which restricts the use of visual information. Rotating to the front, however, would allow visualization of the landing area. Non-fallers took more cross-front steps when pulled towards their preferred, dexterous side, and more cross-back steps when pulled towards their non-preferred, stabilizing side, but only when exposed to perturbation magnitudes At or Above their BTL. This indicates that individuals were using their more dexterous limb to step when taking cross-back steps, but their stabilizing, less dexterous leg to step when taking cross-front steps. Fallers displayed the opposite trends in direction for utilizing cross-over steps, though they were not significant (Fig. 4) and did not display significantly different frequencies of cross-front versus cross-back steps (Fig. 5). One, very speculative, interpretation of these data is that non-fallers are more aware than fallers, either consciously or sub-consciously, of the asymmetrical properties of their preferred or non-preferred legs. Relatedly, and alternatively, fallers may have developed less asymmetry in their limbs over time. These speculations need further investigation to determine a mechanistic link between a propensity to fall and asymmetry in limb function.

There are limitations to the outcomes of this study. First, there are many ways to define the preferred versus non-preferred leg. We chose the one-leg standing portion of the Berg balance test as it is an indicator of standing balance stability; however, it is possible that defining leg preference in other ways may yield different results. Likewise, an assessment of the strength of the observed leg preferences would also be useful for future studies. Second, group trends in step count and step type may be influenced by the numbers of subjects in each group, which are different (Table 1). Additional subjects may also be needed to observe significant differences in trends at the BTL as the results of the present study approached significance. Finally, we used a retrospective fall analysis to group participants in our study; however, in the future, a prospective analysis might enable a more accurate method for identifying fall category.

5. Conclusions

Leg preference does not have a clearly defined relationship to standing balance recovery in older adults. Leg preference was related to the stepping strategy of individuals with no history of falls but only in response to large perturbations. Individuals with a history of falling displayed opposite, though not significant, trends, but significance may have been limited by the number of participants. Asymmetrical trends in stepping responses may indicate a previously unrecognized precipitating factor for falls that should be taken into account when designing balance enhancement interventions for fall prevention; however, the physiological, and perhaps psychological, mechanisms through which leg preference influences standing balance recovery remain to be determined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 AG029510, P30 AG028747, NIDRR Grant H133P100014, the Baltimore VA Medical Center, and Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC).

References

- Alonso AC, Brech GC, Bourquin AM, Greve JM. The influence of lower-limb dominance on postural balance. Sao Paulo Med J. 2011;129:410–413. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802011000600007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata KP, Lockhart TE, Granata KP, Lockhart TE. Dynamic stability differences in fall-prone and healthy adults. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008;18:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes WC, Myers ER, Morris JN, Gerhart TN, Yett HS, Lipsitz LA. Impact near the hip dominates fracture risk in elderly nursing home residents who fall. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;52:192–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00298717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard MJ, Martinez KM, Janssen I, Edwards B, Mille ML, Zhang Y, et al. Lateral balance factors predict future falls in community-living older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1708–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord SR, Rogers MW, Howland A, Fitzpatrick R. Lateral stability, sensorimotor function and falls in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1077–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchies CW, Alexander NB, Schultz AB, Ashton-Miller J. Stepping responses of young and old adults to postural disturbances: kinematics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:506–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb04972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki BE, Edmondstone MA, McIlroy WE. Age-related differences in laterally directed compensatory stepping behavior. J Gerontol. 2000;55A:M270–M277. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.5.m270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew Young PM, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Dynamic margins of stability during human walking in destabilizing environments. J Biomech. 2012;45:1053–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mille ML, Johnson ME, Martinez KM, Rogers MW. Age-dependent differences in lateral balance recovery through protective stepping. Clin Biomech. 2005;20:607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mille ML, Johnson-Hilliard M, Martinez KM, Zhang Y, Edwards BJ, Rogers MW. One Step, Two Steps, Three Steps More … Directional Vulnerability to Falls in Community-Dwelling Older People. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt062. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glt062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nagano H, Begg RK, Sparrow WA, Taylor S. Ageing and limb dominance effects on foot-ground clearance during treadmill and overground walking. Clin Biomech. 2011;26:962–968. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JL, Hilliard MJ, Martinez K, Mille ML, Rogers MW. A simple model of stability limits applied to sidestepping in young, elderly and elderly fallers. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006;1:3305–3308. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.260199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M. Footedness: asymmetries in foot preference and skill and neuropsychological assessment of foot movement. Psychol Bull. 1988;103:179–192. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidcoe PE, Rogers MW. A closed-loop stepper motor waist-pull system for inducing protective stepping in humans. J Biomech. 1998;31:377–381. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt NJ, Grabiner MD. Measures of frontal plane stability during treadmill and overground walking. Gait Posture. 2010;31:380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti M, Speechley M, Ginter S. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1701–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yungher DA, Morgia J, Bair WN, Inacio M, Beamer BA, Prettyman MG, et al. Short-term changes in protective stepping for lateral balance recovery in older adults. Clin Biomech. 2012;27:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]