Abstract

This paper tests the contribution of the toll-like receptors (TLRs), TLR4 in particular, in the initiation and maintenance of paclitaxel-related chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). TLR4 and its immediate down-stream signaling molecules MyD88 and TRIF were increased in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) by western blot by day 7 of paclitaxel treatment. The behavioral phenotype, the increase of both TLR4 and MyD88 was blocked by co-treatment with the TLR4 antagonist LPS-RS during chemotherapy. A similar, but less robust behavioral effect was observed using intrathecal treatment of MyD88 homodimerization inhibitory peptide. DRG levels of TLR4 and MyD88 reduced over the next two weeks, whereas these levels remained increased in spinal cord through day 21 following chemotherapy. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed TLR4 expression in both CGRP- and IB4-positive small DRG neurons. MyD88 was only found in CGRP-positive neurons and TRIF was found both in CGRP- and IB4-positive small DRG neurons as well as in medium and large size DRG neurons. In spinal cord TLR4 was only found co-localized to astrocytes but not with either microglia or neurons. Intrathecal treatment with the TLR4 antagonist lipopolysaccharide-RS (LPS-RS) transiently reversed pre-established CIPN mechanical hypersensitivity. These results strongly implicate TLR4 signaling in DRG and spinal cord in the induction and maintenance of paclitaxel related CIPN.

Keywords: Neuropathy, DRG, spinal cord, TLR4, MyD88, TRIF, LPS-RS

Introduction

Paclitaxel is the frontline chemotherapeutic agent used to treat many of the most common solid tumors, including those of the breast, ovary, and lung34. Peripheral neuropathy is the major dose-limiting side effect of paclitaxel and can force dose-reduction or even discontinuation of therapy thus impacting survival in cancer patients20. Additionally, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) often persists long after cancer treatment is completed and is commonly refractory to current treatment strategies thus impacting rehabilitation, the return to productivity and quality of life in cancer survivors9. Neuropathic pain in general is considered to involve an important role of glial cells and pro-inflammatory immune responses in the underlying basic pathophysiology62; and evidence implicates similar mechanisms in CIPN8,7. Of especial interest in this regard is the observation that paclitaxel engages the same signaling pathway via Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) as the very well-known pro-inflammatory agent, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)12. Paclitaxel binds to and activates TLR4 in macrophages resulting in activation of the NF-κB signal path and the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression identical to that produced by LPS12.

TLR4 is expressed on the surface of innate immune cells, small primary afferent neurons63 and central nervous system cells, including microglia and astrocytes11. Thus, there is a plausible link between TLR4 and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in neural tissue, which could contribute to behavioral hypersensitivity following exposure to chemotherapy drugs. A previous study indicated that TLR4 in the central nervous system plays a role in the development of behavioral hypersensitivity in a rodent model of neuropathic pain60. Rats that lacked functional TLR4 and those that received intrathecally administrated TLR4 anti-sense oligonucleotides showed attenuated nerve injury-induced behavioral hypersensitivity in both the initiation and maintenance phases6. There is no data at present regarding the potential role of TLR4 signaling in paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. This report explores the effects of paclitaxel chemotherapy on the expression of TLR4 in neural tissue and the effects of antagonists to TLR4 and its immediate down-stream signals, myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) and TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF), in reducing paclitaxel-induced behavioral hypersensitivity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250 – 300 g (Harlan, Houston, TX) were used to establish the neuropathic pain model. Rats were housed in temperature- and light-controlled (12 hour light/dark cycle) conditions with food and water available ad libitum. All 169 rats used in the study were included in the behavioral analysis portions and then used in either follow-up pharmacological, immunohistochemistry or western blot analysis. The numbers of rats in each of these studies are detailed in the relevant sections. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Every procedure was designed to minimize discomfort to the animals and to use the fewest animals needed for statistical analysis.

Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathy Model

Rats were treated with paclitaxel (TEVA Pharmaceuticals, Inc., North Wales, PA) as previously described69 based on the protocol of Polomano et al48. In brief, pharmaceutical grade Taxol® was diluted with sterile saline from the original stock concentration of 6 mg/mL (in 1:1 Cremophor EL: ethanol) to 1 mg/mL and given at a dosage of 2 mg/kg intraperitoneally (i.p.) every other day for a total of four injections (days 1, 3, 5, and 7) resulting in a final cumulative dose of 8mg/kg. Control animals received an equivalent volume of the vehicle only, which consisted of equal amounts of Cremophor ELR and ethanol diluted with saline to reach a concentration of vehicle similar to the paclitaxel concentration. No abnormal spontaneous behavioral changes were noted during or after paclitaxel or vehicle treatment.

TLR4 and MyD88 Antagonist Administration

To assess the role of the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway in maintaining paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain, 20 µg of the TLR4 antagonist LPS derived from R. sphaeroides (LPS-RS) in 20 µl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) or 500 µM of MyD88 homodimerization inhibitory peptide (MIP) in PBS (Imgenex, San Diego, CA) were injected intrathecally by L5 puncture at day 14 following confirmation of paclitaxel-induced mechanical hypersensitivity. The rats were briefly anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and flexed over a tube and a 27-gauge needle inserted between the L5-S1 vertebrae with a deflection of the tail indicating entry to the subarachnoid space. The dose of LPS-RS was chosen based on previously published studies whereas the dose of MIP was based on the results of pilot studies wherein rats that received a dose of 100 µM MIP showed no effect on paclitaxel CIPN and rats injected with 1mM MIP showed pronounced motor impairment. PBS (20 µl) and 500 µM MyD88 control peptide (CP, also in 20 µl PBS) were used separately as controls. To test whether LPS-RS may have an effect in preventing paclitaxel induced CIPN, rats were treated with LPS-RS beginning 2 days before and then daily through day 2 after paclitaxel treatment. It was not possible to test the role of TRIF signaling in maintaining paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain because there is no inhibitor available.

Mechanical withdrawal test

Mechanical withdrawal threshold was tested before, during and following paclitaxel treatment by an experimenter blinded to treatment groups during the mid-light hours (10AM-2PM). The 50% paw withdrawal threshold in response to a series of eight von Frey hairs (0.41 to 15.10 g) was examined by the up-down method, as described previously beginning with a filament with a bending force of 2.0g19. Animals were placed under clear acrylic cages atop a wire mesh floor. The filaments were applied to the paw just below the pads with no acceleration at a force just sufficient to produce a bend and held for 6–8 s. A quick flick or full withdrawal was considered a response.

Rotarod test

Rotarod performance was evaluated in the rats that were treated with intrathecal drugs to ensure a lack of treatment effects on motor function. Briefly, the rats were trained on the rotarod apparatus for 3 days prior to any intrathecal drug applications. Acceleration of the rotarod was set to increase from 0 to 40 rpm over 5 minutes. Each rat was tested 3 times at 5-minute intervals, and the average of the latency to drop from the rod for all trials was recorded. The rats were again tested before and then 3 hours after treatment with MIP or CP.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, 100 mg/kg, i.p., Lundbeck, Inc., Deerfield, IL) and perfused through the ascending aorta with warm saline followed by cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M PBS. The L4 and L5 DRG were removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 6 hours, and then cryo-protected in 30% sucrose solution. The L4 and L5 spinal cord segments were also removed fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 hours, and then cryo-protected in 30% sucrose solution. Transverse spinal cord sections (15 µm) and longitudinal DRG sections (8 µm) were cut in a cryostat, mounted on gelatin-coated glass slides (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) and processed for immunofluorescent staining. After blocking in 5% normal donkey serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in 1% normal donkey serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS containing primary antibodies against the following targets: TLR4 (rabbit anti-rat, 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), MyD88 (rabbit anti-rat, 1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), TRIF (rabbit anti-rat, 1:200 Abcam, Cambridge, MA), GFAP (mouse anti-rat, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), OX-42 (mouse anti-rat, 1:1000; Serotec, Raleigh, NC), NeuN (mouse anti-rat, 1:1000; Millipore, Billerica, MA), IB4 1:1000 BS-Isolectin B4 FITC Conjugate, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and CGRP (mouse anti19 rat, 1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). After washing, the sections were then incubated with Cy3-, Cy5- or FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Sections were viewed under a fluorescent microscope (Eclipse E600; Nikon, Japan). For a given experiment, all images were taken using identical acquisition parameters and experimenters blinded to treatment groups. To measure cell size, each individual neuron, including the nuclear region, was graphically highlighted. For each positive staining of TLR4, MyD88 and TRIF with IB4 or CGRP co-localization, the numbers of total and positive for co-localization neurons from 3 sections of DRG of 3 rats were counted; data from the 3 sections of same rat were averaged, and then mean values used for Mann-Whitney U test comparisons. The percentages of positive neurons to total neurons were calculated and statistically analyzed. To determine whether intrathecal injection could reach and affect signaling in both the DRG as well as the spinal cord level 20 µl of Alexa488-labeled mismatch TLR4 oligonucleotide (Invitrogen) was injected by lumbar puncture and the tissues removed, sectioned and mounted as described above. All images were analyzed using NIC Elements imaging software (Nikon, Japan).

Western Blot Analysis

L4 and L5 DRGs and L4–L5 spinal cord segments were collected from rats that were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, 100 mg/kg, i.p.). The samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissues were disrupted in RIPA lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 µg/mL leupeptin) mixed with 1 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (P0044 and P5726, Sigma) on ice. The supernatant was then collected and denatured with sample buffer (X5) consisting of 0.25 M Tris-HCl, 52% glycerol, 6% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 5% β-Mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue for 10 minutes at 70°C. Lysates (total protein: 20 µg) were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad). After blocking with 5% fat-free milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST;137 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM Tris, 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 hour at room temperature and then incubated with different antibodies: TLR4 (rabbit anti-rat, 1:1000, Proteintech, Chicago, IL), MyD88 (rabbit anti-rat, 1:1000, Imgenex, San Diego, CA), TRIF (rabbit anti-rat, 1:4000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and β-actin (mouse anti-rat, 1:10,000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 5% fat-free milk in TBST overnight at 4°C. After being washed with TBST, the membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit antibody (labeled with horseradish peroxidase, Calbiochem, CA) diluted with 5% fat-free milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature and TLR4, MyD88 and TRIF were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The blots were scanned with Spot Advanced and Adobe Photoshop 8.0 (Adobe, Inc., San Jose, CA), and the band densities were detected and compared using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). The data from 3 rats per treatment group were averaged for group comparisons.

Data Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) and analyzed with GraphPad Prism 5. Behavioral data (figures 1 and 7) were analyzed with 2-way analysis of variance (treatment X time) followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. The cell counts for immune-positive neurons and the percentages of neurons that co-localized with IB4 or CGRP were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (figures 3 and 5).

Figure 1.

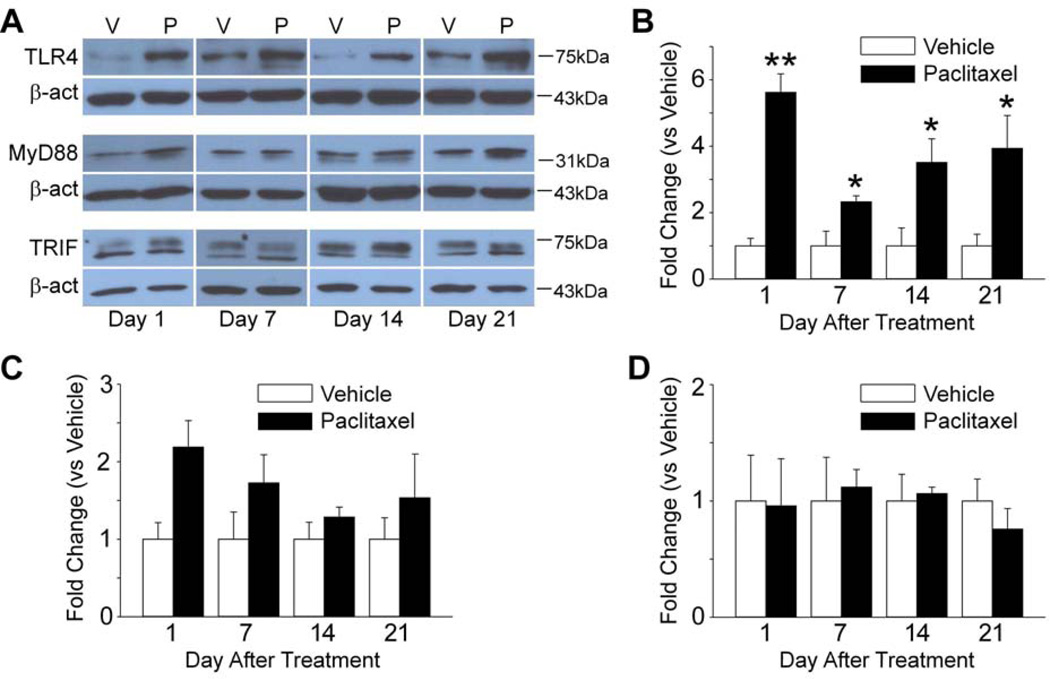

TLR4, MyD88 and TRIF are increased in the DRG in paclitaxel CIPN. The scatter and line plot in A shows the mean (and standard error) mechanical withdrawal threshold (in grams) for vehicle (n=16) (open circles) and paclitaxel treated rats (n=16) (filled circles). A decrease in withdrawal threshold was observed at day 1 after chemotherapy that became more pronounced and significantly different from that in the vehicle treated group by day 7. Withdrawal threshold remained significant lower than in the vehicle group over the remainder of the time frame observed. The representative western blot images shown in B and C and D illustrate that the expression of TLR4 (B) and MyD88 (C) was increased by day 1 of chemotherapy, while TRIF (D) was increased at day 7 in the DRG, but then fell back to the baseline level by two weeks after treatment and then remained at this level over the time frame observed. The bar graphs summarize the grouped data and indicate that the level of expression of TLR4 (B), MyD88 (C) and TRIF (D) in the DRG was significantly increased in the paclitaxel treated rats (filled bars) compared to the vehicle treated rats (open bars). N = 3 for each group in B through D. β-act = beta-actin, V = vehicle, P = paclitaxel, ** = p < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001. (F=14.38 (4, 127) in A).

Figure 7.

Reversal and prevention of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain by intrathecal injection of a TLR4 antagonist (LPS-RS) and MyD88 homodimerization inhibitory peptide (MIP). After a baseline (BL) behavioral test, rats received intraperitoneal injection of paclitaxel (P) or vehicle (V). In panel A, the rats were also treated every 12 hours with 20 µg TLR4 antagonist (LPS-RS) or PBS beginning 2 days before and continuing to 2 days after paclitaxel or vehicle treatment. The paclitaxel- LPS-RS group (n=8) rats showed a significant partial prevention of mechanical hypersensitivity compared with the paclitaxel-PBS group rats (n=8) (A). Vehicle-treated rats receiving i.t PBS (n=5) or LPS-RS (n=5) showed no changes from the baseline measures (A). In B and C paclitaxel-induced mechanical hypersensitivity was confirmed at 14 days after treatment and then rats were treated with 20 µg of the TLR4 antagonist LPS-RS (n=7) or PBS (n=4) (i.t., B) or 500 µM MyD88 inhibitor peptide (n=8) (MIP, C) or 500 µM MyD88 control peptide (n=8) (CP, C). LPS-RS (black circles) transiently reversed the mechanical hyper-responsiveness with peak effect at 3h (B). Similarly, MIP (black circles) reversed mechanical hyper-responsiveness with a peak effects at 3 hours, but the duration in effect was sorter as mechanical withdrawal threshold returned to baseline by 6 hours after injection (C). No significant difference was observed in the rotarod test of the rats between MIP group 500 µM (n=4) and CP 500 µM group (n=4) (D). (*=p < 0.05; **=p < 0.01; ***=p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the paclitaxel-LPS-RS groups and paclitaxel-MIP groups versus the paclitaxel-PBS and paclitaxel-CP groups. Crosses indicate significant decrease in mechanical withdrawal threshold in paclitaxel treated groups to baseline measures (+++ and ***= p < 0.001; ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05). (F=4.98 (12, 115), 4.18 (7, 72), 8.84 (21, 176) and 0.01 (1, 12) for A, B, C and D, respectively). The representative photographs shows a low power view of the DRG (Fig. 7E) and high power view of some two DRG neurons (Fig. 7F) showing that Alexa488- labeled oligonucleotide reached the L5 DRG and was found in neurons 3 days following i.t. injection by lumbar puncture (20 µl). Scale bar in E and F is 100 µm and 10 µm.

Figure 3.

TLR 4 is increased and co-localized to subsets of DRG neurons following paclitaxel chemotherapy. The representative immunohistochemistry images in the top line shows that the expression of TLR4 (red) in the DRG is normally quite low in vehicle-treated rats (A) and in naive rats (data not shown) but becomes quite pronounced by day 7 following paclitaxel treatment (B). The bar graphs inset in A shows that the TLR4+ neurons are predominantly small size with a diameter less that 30 µm. Double immunohistochemistry shown in the second line indicate that TLR4 expression (red) is found in subsets of CGRP positive (blue) neurons (C, co-localization indicated by purple, arrow indicated) as well as in IB4 positive (green) neurons (D, co17 localization indicated by yellow arrow indicated). The merged image in E and the bar graph shown F indicate that TLR4 was expressed in a larger percentage of IB4 positive neurons than CGRP positive neurons as well as in a substantial proportion of DRG neurons that were neither IB4 nor CGRP positive. The bar graphs also illustrate that there was no change in the proportions of IB4+, CGRP+, or the combinations of DRG neurons following paclitaxel treatment. Scale bar= 100 µm. *** = P < 0.001. (F=14.69 (2, 48).

Figure 5.

TRIF is increased and co-localized to subsets of DRG neurons following paclitaxel chemotherapy. The representative immunohistochemistry images in the top line shows that the expression of TRIF (red) in the DRG is normally quite low in vehicle-treated rats (A) and in naive rats (data not shown) but becomes quite pronounced by day 7 following paclitaxel treatment (B). The bar graphs inset in A shows that TRIF+ neurons are in large, medium and small size neurons. Double immunohistochemistry shown in the second line indicates that TRIF expression (red) is found in subsets of CGRP positive (blue) neurons (C, co-localization indicated by purple, arrow indicated) as well as in IB4 positive (green) neurons (D, co-localization indicated by yellow, arrow indicated). The merged image in E and the bar graph shown F indicates that TRIF was expressed in a substantial proportion of DRG neurons that were neither IB4 nor CGRP positive. Scale bar= 100 µm. (F=1.65 (2, 30) for F).

Immunohistochemistry and western blot data (figures 1, 2, an 8) were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 2.

TLR4 but not MyD88 or TRIF are increased in the L5 spinal dorsal horn in paclitaxel CIPN. The representative western blot images shown in A illustrate that the expression of TLR4 in the spinal cord was increased by day 1 of chemotherapy, decreased some by day 7 but then showed increasing expression at days 14 and 21. The representative western blots shown in A also illustrate that the expression of MyD88 and TRIF did not change over the time frame observed. The bar graphs summarize the grouped data and indicate that the level of expression of TLR4 (B) in the spinal cord was significantly increased in the paclitaxel treated rats (filled bars) compared to the vehicle treated rats (open bars) but the expression on MyD88 (C) and TRIF (D) were not significantly increased. N = 3 for each group. β-act = beta-actin, V = vehicle, P = paclitaxel, ** = p < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001.

Figure 8.

The increase of MyD88, but not TRIF is prevented in the DRG in paclitaxel CIPN under LPS-RS treatment. The representative western blot images shown in A illustrate that the increasing expression of MyD88 in the DRG was blocked by day 7 of LPS-RS. The representative western blots shown in B illustrate that the expression of TRIF did not change. The bar graphs summarize the grouped data and indicate that the level of expression of MyD88 (A) and TRIF (B) in the DRG in the paclitaxel-LPS-RS treated rats (filled bars) compared to the paclitaxel-PBS treated rats (open bars). N = 3 for each group. β-act = beta-actin, P = paclitaxel-PBS, L = paclitaxel-LPS-RS, ** = p < 0.01.

Results

Changes in Expression of TLR4, MyD88 and TRIF in Rats with Paclitaxel CIPN

Rats treated with paclitaxel showed a decrease in mechanical withdrawal threshold by day 1 following treatment that became more pronounced over time achieving a significant difference from baseline by day 7 of treatment (Fig. 1A). The decrease in threshold became maximal at day 14 and this was sustained through day 21. In contrast, although rats treated with vehicle showed a small decrease in withdrawal threshold at day 1 this returned to the baseline level by day 3 and remained stable throughout the experiment (Fig. 1A).

All paclitaxel-treated animals (positive controls) that were advanced to the western and immunohistochemistry experiments had confirmed mechanical hypersensitivity. The expression of TLR4 was significantly increased in the L4-5 DRG beginning by day 1 after paclitaxel treatment and this was sustained through day 7 in comparison to rats that received vehicle (Fig. 1B). The expression of TLR4 then fell to significantly below the baseline level by day 14 and remained such through day 21 (Fig. 1B). The expression of MyD88 and TRIF in the DRG paralleled that of TLR4. MyD88 showed a pronounced and significant elevation by day 1 that was sustained through day 7 after paclitaxel and then dropping back to baseline when measured at day 14 and then significantly below baseline at day 21 (Fig. 1C). TRIF showed a robust elevation by day 7 after paclitaxel and then returned back to baseline when measured at day 14 and day 21 (Fig. 1D).

The expression of TLR4 in the spinal cord showed both similarities and differences to that observed in DRG. Like observed in the DRG, spinal TLR4 expression was significantly increased by day 1 and this was sustained but also somewhat lower at day 7 after paclitaxel treatment. However, unlike observed in the DRG, the expression of TLR4 showed an apparent resurgence in the spinal cord at the later time points observed at days 14 and 21 (Fig. 2A, B). Surprisingly, the expression of MyD88 and TRIF in spinal cord showed no changes over time following paclitaxel in treated rats versus vehicle controls (Fig. 2A, C, D).

Cellular Localization of TLR4, MyD88 and TRIF in DRG

Immunohistochemistry was used to define the cellular localization of TLR4, MyD88 and TRIF in DRG and spinal cord at the peak of increased expression at day 7 after paclitaxel treatment. As shown in Figure 3, TLR4 was increased in small neurons after paclitaxel treatment compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 3A, B). More specifically, TLR4 was found to be co-localized in both CGRP-positive and in IB4-positive small DRG neurons (Fig. 3C–F). Interestingly however, MyD88 was co-localized only in CGRP-positive but not IB4-positive neurons (Fig. 4A–D). TRIF was found to be co-localized in both CGRP-positive and in IB4-positive small DRG neurons, and also localized to medium and large size DRG neurons (Fig. 5A–F). No co-localization was observed for TLR4 in either in NF200 or GFAP positive neurons or cell profiles in DRG, respectively (data not shown).

Figure 4.

MyD88 is increased and co-localized to subsets of DRG neurons following paclitaxel chemotherapy. The representative immunohistochemistry images in the top line shows that the expression of MyD88 (red) in the DRG is normally quite low in vehicle-treated rats (A) and in naive rats (data not shown) but becomes quite pronounced by day 7 following paclitaxel treatment (B). Double immunohistochemistry shown in the second line indicate that MyD88 expression (red) is found in subsets of CGRP positive (blue) neurons (C, co-localization indicated by purple, arrow indicated) but without in IB4 positive (green) neurons (D, co-localization in yellow). Scale bar= 100 µm. * = p < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01.

Distribution of TLR4 after Paclitaxel Treatment in Dorsal Horn of Spinal Cord

Consistent with our western blot results (Fig. 2A) immunohistochemistry showed a significant increase in the expression of TLR4 at day 7 after paclitaxel treatment in spinal cord dorsal horn (Fig. 6B) that was present at only very low levels in rats treated with vehicle (Fig. 6A). TLR4 was found co-expressed in GFAP-positive cells (Fig. 6C–D) but not in NeuN or OX42 positive cells (Fig. 6E–F and Fig. 6G–H, respectively).

Figure 6.

Spinal cord expression of TLR4 is increased in astrocytes but not microglia or neurons in paclitaxel-treated rats. TLR4 staining is relatively low in the spinal dorsal horn in vehicle treated rats (A) but becomes quite prominent at day 7 following paclitaxel treatments (B). Double immunohistochemistry reveals that TLR4 co-localizes to GFAP positive cells (C and higher magnification in D, arrow indicated) but is not found to co-localize with NeuN positive (E and F) or OX42 positive (G and H). Scale bar in A, B, C, E and G is 100 µm and in D, F and H is 50 µm.

Reversal and Prevention of Paclitaxel-induced CIPN by LPS-RS and MIP

The contribution of TLR4 and MyD88 to paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain was assessed by testing the effects of intrathecally administered LPS-RS and MIP on both pre-established paclitaxel CIPN and on the induction of paclitaxel CIPN (Fig. 7A–C). LPS-RS was tested to determine whether blockade of TLR4 signaling might be useful in preventing paclitaxel CIPN. LPS-RS (20 µg in 20 µl) or PBS (20 µl) was given by i.t. injection every 12 hours beginning two days before and continuing through 2 days after the chemotherapy drug. LPS-RS had no effect on baseline mechanical withdrawal threshold and showed no interaction with the paclitaxel vehicle over time (Fig. 7A). The paclitaxel-PBS treated rats (n=8) showed the expected decrease in mechanical withdrawal threshold that was significant from the vehicle treated rats by day 7 (Fig. 7A). In contrast the paclitaxel-LPS-RS rats showed only a partial development of mechanical hypersensitivity that was significantly less when compared with the paclitaxel-PBS treated rats (Fig. 7A).

In the second experiment where in LPS-RS was used to reverse paclitaxel-induced CIPN, two groups were first treated with paclitaxel and hypersensitivity to mechanical stimuli was confirmed in each group such that there was a statistical difference between the baseline measurement and that at day 14 for both while neither treatment group was different from the other (Fig. 7B). Rats in both groups were then given a single intrathecal dose of either 20 µg LPS-RS (n=7) in 20 µl PBS or 20 µl PBS alone (n=4). The LPS-RS group showed an increase in mechanical withdrawal threshold that was evident by two hours after treatment and this became significant from the PBS group at 3 hours after treatment. The effect of LPS-RS then subsided over time such that no difference from the PBS treated group remained at 24 hours after injection (Fig. 7B).

The effect of inhibiting MyD88, the immediate down-stream signal of TLR4, was tested in a similar fashion. Rats were treated with either paclitaxel or vehicle and then tested to verify establishment of the CIPN model at day 14 after treatment (Fig. 7C). The paclitaxel-treated rats showed a mechanical withdrawal threshold significantly lower that the vehicle-treated rats but that was not different from each other. The rats were then treated with MIP (n=8 in paclitaxel group, n=5 in vehicle group) or CP (n=8 in paclitaxel group, n=5 in vehicle group), and mechanical withdrawal threshold was reevaluated. MIP-treated rats showed a significant increase in mechanical withdrawal threshold that was evident by one hour and significant from the CP-treated paclitaxel group by 2 hours after injection (Fig. 7C). The peak effect of MIP in reversing paclitaxel CIPN was observed at 3 hours after injection and then waned with complete loss of effect by 6 hours after drug delivery (Fig. 7C). Finally, none of the doses of intrathecal MIP used here had any effect on motor performance assessed in the rotarod test (Fig. 7D).

To determine whether the intrathecal route of drug administration would reach and so affect signaling in the DRG as well as the spinal cord, 20 µl of Alexa488-labeled mismatch TLR4 oligonucleotide (Invitrogen) was injected and the DRG removed 3 days later, sectioned and mounted for visualization. A representative photograph showing label in both the DRG and spinal cord is shown in Figs 7E and F.

Changes in Expression of MyD88 and TRIF in Rats after LPS-RS treatment

Our data showed that intrathecal injection of the TLR4 antagonist LPS-RS prevented the induction of paclitaxel-induced pain (Fig. 7A). Since MyD88 and TRIF are down-stream signaling molecules of TLR4, we performed experiments to verify whether LPS-RS treatment could block the paclitaxel-induced increase of MyD88 and TRIF in DRG. The expression of MyD88 was significantly decreased in the L4-5 DRG at day 7 after LPS-RS treatment in paclitaxel treated rats in comparison to rats that received vehicle (Fig. 8A). The increase of expression of TRIF at day 7 was not however affected by LPS-RS treatment (Fig. 8B).

Discussion

A possible mechanism of nerve damage in CIPN is derived from several lines of evidence that show that pro-inflammatory cytokines produce sensory fiber dysfunction and pain in many diverse models of neuropathic and inflammatory pain45,24,51,56,54,53,55,58,53,66,25, and that these are also induced by the major chemotherapy drugs65,49. The cytokines IFNα/γ, TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 are increased in vitro following exposure of macrophages to paclitaxel68,42 or cisplatin3,32,46 and the chemokine CCL2 is increased in DRG and spinal cord in the early stages of taxol chemotherapy in subsets of DRG neurons and spinal astrocytes69. Loss of function studies using anti-CCL2 antibodies protected animals from taxol-induced hyperalgesia and loss of peripheral skin innervation density. A key observation is that the pattern of cytokine gene induction, synthesis and release by chemotherapeutics is very similar to that induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)4,26. This strongly implicates a role for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in CIPN given that TLR4 is the receptor in the innate immune system activated by LPS. TLR4 is expressed on the cell surface of neurons and glial cells in human brain11 and the data shown here indicate that TLR4 is expressed in dorsal horn and subsets of DRG neurons and glial cells. TLR4 antagonists reduce nerve injury induced hyperalgesia in mice and rats6,36, and knockout of either TLR4 or its signaling co-factor CD14 results in abbreviated post-inflammatory hyperalgesia, reduced spinal glial responses to inflammation, and reduced neuropathic pain22,14,60. The chemotherapeutic cisplatin increased expression of TLR4 on peritoneal macrophages in vitro and primed their cytokine response to L929 cells21; and the data shown here indicates a similar effect in vivo in both dorsal horn and DRG following paclitaxel. Finally, TLR4 mediated induction of hyperalgesia by LPS includes effects of damage associated molecular pattern (DAMPs) components including heat shock protein 90 (HSP90)35 and high14 mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) protein18,61. HSP90 and/or HMGB1 may be directly induced from DRG neurons or glia by damage to cell organelles or DNA by chemotherapy drugs39; and both directly induce hyperalgesia when exogenously administered50,30. An increase in HSP90 is induced also following proteasome inhibition with bortezomib most likely due to accumulation of mis-folded intracellular proteins64. Thus, TLR4 activation and/or DAMPs signaling may be a common entry point of pathophysiology shared amongst chemotherapeutics that ultimately results in the generation of the shared clinical CIPN phenotype.

Signal transduction following TLR4 activation occurs through 2 distinct pathways. One pathway results in the induction of a MyD88-dependent cascade leading to early NF-κB activation and subsequent increased synthesis and release of multiple cytokines and chemokines43,47. The second cascade is TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-dependent and leads to delayed NF-κB activation and interferon-β production43,47. There is growing evidence indicating that TLR4, along with other TLRs, share the same signaling cascade as the IL-1 receptor12,44. MyD88 is recruited to the receptor as an adaptor protein, and this recruitment is followed by activation of IL-1 receptor-associated kinases and TNF receptor-associated factor 6, which leads to NF-κB activation12. Alternatively, LPS also increases mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) function and NF-κB nuclear translocation occur in MyD88-knockout cells, indicating that non-MyD88 signaling also contributes to the biological response to LPS via TLR438. The MyD88 activation pathway, is recruited by all TLRs except TLR3, and leads to activation of NF-κB, and the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and interleukin (IL)-138.

Our results showed a transient analgesic effect of i.t LDP-RS and the MyD88 inhibitor at day 14 following paclitaxel, yet there was no increase in TLR4 expression in DRG and no elevated expression of MyD88 in DRG or spinal cord at this time point (Fig. 1 and 2). Indeed, MyD88 was not observed in spinal cord. These results raise a number of interesting questions that will form the basis for several lines of interesting follow-up investigation. The results with both antagonists suggest there is some means for tonic stimulation at TLR4 that is separate from that provided at early time points where paclitaxel is present and presumably providing this stimulus. One logical candidate would seem to be reactive oxygen species that have been implicated by others in the pathophysiology of CIPN29,31 and that also stimulate TLR41. Alternatively, chemotherapeutics stimulate the release of damage associated molecular pattern proteins including HMGB140 that both stimulates TLR4 in neurons2 and that promotes neuropathic pain30. Indeed, it is intriguing to speculate that these supplemental players could account for both the coasting often seen in patients and account for the transition to a chronic pain condition given that each could support a self-sustaining positive feed-back signaling loop. The lack of MyD88 in spinal cord and its presence in only a subset of DRG neurons also indicates that parallel signal pathways contribute to CIPN. TLR4 and TRIF were shown to be the expressed on both IB4-positive and CGRP-positive neurons in DRG, but MyD88 expression was increased only in CGRP-positive neurons. No TLR4 expression was found in large neurons, but somewhat surprisingly TRIF expression was found in large neurons. TRIF is shared by both TLR3 and TLR4 signaling, and produces type I interferon33,43. Hence, TLR3 may also be involved in paclitaxel-induced CIPN. In that a key role of IB4+ DRG neurons in CIPN has been demonstrated37 it would seem likely that there is also a prominent role for MAPK in this subset of cells in the pathophysiology of CIPN that remains to be defined.

It has become widely recognized that glial cells both in peripheral nerve, dorsal root ganglion and in the spinal cord react following peripheral inflammation or nerve injury and contribute to the pathophysiology of the resulting hyperalgesia41,13,70,59. Moreover, a key component in the glial response is mediated by TLR457,22. Microglia has arguably received the majority of attention as the key glial elements involved in nerve injury related pain5,23. Yet, a striking feature of the CIPN glial phenotype is an apparent major role of spinal astrocytes and much less prominent or complete lack of recruitment of microglia72,71. Spinal astrocytes become hypertrophic and show increased expression of GFAP in both paclitaxel and oxaliplatin related CIPN71,67. In addition, astrocytes in CIPN rats show increased expression of the gap junction protein connexin 43 as well as down regulation of glutamate transporters15,71. Patients not only complain of on-going pain with CIPN, but also when pain is aggravated by peripheral stimuli, that pain supercedes their on-going pain and importantly it may last for minutes, hours, or sometimes days9,10,16,28,27. Experimental animals similarly show exaggerated nocifensive behavioral reactions to peripheral stimuli in models of chemoneuropathy15,17. Given that skin innervation density is depleted in all models of CIPN studied thus far8,7,52 it seems there must be some mechanism for augmentation of signaling by the residual fibers. One potential mechanism is down-regulation of glutamate transporters in spinal astrocytes. The data shown here raises the question as to the relationship between TLR4 activation and the change in spinal astrocyte phenotype. Given that the chemotherapeutics that cause CIPN poorly penetrate to the CNS it is of further keen interest as to what the potential signal or link may be between peripheral and central TLR4 activation.

Perspective.

The Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and MyD88 signaling pathway could be a new potential therapeutic target in paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS 046606) and the National Cancer Institute (CA124787).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Asehnoune K, Strassheim D, Mitra S, Kim JY, Abraham E. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2004 Feb 15;172:2522–2529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balosso S, Liu J, Bianchi ME, Vezzani A. Disulfide-Containing High Mobility Group Box-1 Promotes N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Function and Excitotoxicity by Activating Toll-Like Receptor 4-Dependent Signaling in Hippocampal Neurons. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014 Jan 3; doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu S, Sodhi A. Increased release of interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor by interleukin-2-induced lymphokine-activated killer cells in the presence of cisplatin and FK-565. Immunol Cell Biol. 1992;70(Pt 1):15–24. doi: 10.1038/icb.1992.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beattie EC, Stellwagen D, Morishita W, Bresnahan JC, Ha BK, von Zastrow M, Beattie MS, Malenka RC. Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFa. Science. 2002;295:2282–2285. doi: 10.1126/science.1067859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beggs S, Salter MW. Stereological and somatotopic analysis of the spinal microglial response to peripheral nerve injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:624–633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bettoni I, Comelli F, Rossini C, Granucci F, Giagnoni G, Costa B. Glial TLR4 receptor as new target to treat neuropathic pain: Efficacy of a new receptor antagonist in a model of peripheral nerve injury in mice. GLIA. 2008;56:1312–1319. doi: 10.1002/glia.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyette-Davis J, Dougherty PM. Protection against oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and intraepidermal nerve fiber loss by minocycline. Exp Neurol. 2011;229:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyette-Davis J, Xin W, Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Intraepidermal nerve fiber loss corresponds to the development of Taxol-induced hyperalgesia and can be prevented by treatment with minocycline. Pain. 2011;152:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyette-Davis JA, Cata JP, Zhang H, Driver LC, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy WR, Dougherty PM. Follow-up psychophysical studies in bortezomib-related chemoneuropathy patients. J Pain. 2011 Jun 22; doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyette-Davis JA, Cata JP, Zhang H, Driver LC, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy WR, Dougherty PM. Follow-up psychophysical studies in bortezomib-related chemoneuropathy patients. J Pain. 2011;12:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bsibsi M, Ravid R, Gveric D, Van Noort JM. Broad expression of Toll-like receptors in the human central nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:1013–1021. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.11.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrd-Leifer CA, Block EF, Takeda K, Akira S, Ding A. The role of MyD88 and TLR4 in the LPS-mimetic activity of taxol. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2448–2457. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200108)31:8<2448::aid-immu2448>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campana WM. Schwann cells: Activated peripheral glia and their role in neuropathic pain. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao L, Tanga FY, DeLeo JA. The contributing role of CD14 in Toll-like receptor 4 dependent neuropathic pain. Neuroscience. 2009;158:896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cata JP, Weng HR, Chen JH, Dougherty PM. Altered discharges of spinal wide dynamic range neurons and down-regulation of glutamate transporter expression in rats with paclitaxel-induced hyperalgesia. Neuroscience. 2006;138:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cata JP, Weng H-R, Dougherty PM. Clinical and experimental findings in humans and animals with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Minerva Anes. 2006;72:151–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cata JP, Weng H-R, Dougherty PM. Behavioral and electrophysiological studies in rats with cisplatin-induced chemoneuropathy. Brain Res. 2008;1230:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang Y, Huang X, Liu Z, Han G, Huang L, Xiong Y-C, Wang Z. Dexmedetomidine inhibits the secretion of high mobility group box 1 from lipopolysaccharide- activated macrophages in vitro. J Surg Res. 2012:E1–E7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Meth. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhry V, Rowinsky EK, Sartorius SE, Donehower RC, Cornblath DR. Peripheral neuropathy from taxol and cisplatin combination chemotherapy: Clinical and electrophysiological studies. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:304–311. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauhan P, Sodhi A, Shrivastava A. Cisplatin primes murine peritoneal macrophages for enhanced expression of nitric oxide, proinflammatory cytokines, TLRs, transcription factors and activation of MAP kinases upon co-incubation with L929 cells. Immunobiol. 2009;214:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christianson CA, Dumalo DS, Stokes JA, Dennis EA, Svensson CI, Corr M, Yaksh TL. Spinal TLR4 mediates the transition to a persistent mechanical hypersensitivity after the resolution of inflammation in serum-transferred arthritis. Pain. 2011;152:2881–2891. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coull JAM, Beggs S, Boudreau D, Boivin D, Tsuda M, Inoue K, Gravel C, Salter MW, DeKoninck Y. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature. 2005;438:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui J-G, Holmin S, Mathiesen T, Meyerson BA, Linderoth B. Possible role of inflammatory mediators in tactile hypersensitivity in rat models of mononeuropathy. Pain. 2000;88:239–248. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunha JM, Cunha FQ, Poole S, Ferreira SH. Cytokine- mediated inflammatory hyperalgesia limited by interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1418–1424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding AH, Porteu F, Sanchez E, Nathan CF. Shared actions of endotoxin and taxol on TNF receptors and TNF release. Science. 2002;248:370–372. doi: 10.1126/science.1970196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dougherty PM, Cata JP, Burton AW, Vu K, Weng HR. Dysfunction in multiple primary afferent fiber subtypes revealed by quantitative sensory testing in patients with chronic vincristine-induced pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:166–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dougherty PM, Cata JP, Cordella JV, Burton A, Weng H-R. Taxol-induced sensory disturbance is characterized by preferential impairment of myelinated fiber function in cancer patients. Pain. 2004;109:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doyle T, Chen Z, Muscoli C, Bryant L, Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S, Dagostino C, Ryerse J, Rausaria S, Kamadulski A, Neumann WL, Salvemini D. Targeting the overproduction of peroxynitrite for the prevention and reversal of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6149–6160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6343-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman P, Due MR, Ripsch MS, Khanna R, White FA. The persistent release of HMGB1 contributes to tactile hyperalgesia in a rodent model of neuropathic pain. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:180. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fidanboylu M, Griffiths LA, Flatters SJ. Global inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) inhibits paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gan XH, Jewett A, Bonavida B. Activation of human peripheral-blood-derived monocytes by cis- diamminedichloroplatinum: enhanced tumoricidal activity and secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Nat Immun. 1992;11:144–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hacker G, Suttner K, Harada H, Kirschnek S. TLR-dependent Bim phosphorylation in macrophages is mediated by ERK and is connected to proteasomal degradation of the protein. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1749–1757. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hagiwara H, Sunada Y. Mechanism of taxane neurotoxicity. Breast Cancer. 2004;11:82–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02968008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hutchison MR, Ramos KM, Loram LC, Wieseler J, Sholar PW, Kearney JJ, Lewis MT, Crysdale NY, Zhang Y, Harrison JA, Maier SF, Rice KC, Watkins LR. Evidence for a role of heat shock protein-90 in Toll like receptor 4 mediated pain enhancement in rats. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1821–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutchison MR, Zhang Y, Brown K, Coats BD, Shridhar M, Sholar PW, Patel SJ, Crysdale NY, Harrison JA, Maier SF, Rice KC, Watkins LR. Non stereoselective reversal of neuropathic pain by naloxone and naltrexone: Involvement of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:20–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph EK, Chen X, Bogen O, Levine JD. Oxaliplatin acts on IB4-positive nociceptors to induce an oxidative stress-dependent acute painful peripheral neuropathy. J Pain. 2008;9:463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.01.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kono H, Rock KL. How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:279–289. doi: 10.1038/nri2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu L, Yang M, Kang R, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Yu Y, Xie M, Yin X, Livesey KM, Lotze MT, Tang D, Cao L. HMGB1-induced autophagy promotes chemotherapy resistance in leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2011;25:23–31. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milligan ED, Watkins LR. Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrn2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Brien JM, Jr, Wewers MD, Moore SA, Allen JN. Taxol and colchicine increase LPS-induced pro-IL-1 beta production, but do not increase IL-1 beta secretion. A role for microtubules in the regulation of IL-1 beta production. J Immunol. 1995 Apr 15;154:4113–4122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Neill LA, Bowie AG. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll2 like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Neill LA, Dunne A, Edjeback M, Gray P, Jefferies C, Wietek C. Mal and MyD88: adapter proteins involved in signal transduction by Toll-like receptors. J Endotoxin Res. 2003;9:55–59. doi: 10.1179/096805103125001351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okamoto K, Martin DP, Schmelzer JD, Mitsui Y, Low PA. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine gene expression in rat sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Exp Neurol. 2001;169:386–391. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pai K, Sodhi A. Effect of cisplatin, rIFN-Y, LPS and MDP on release of H2O2, O2- and lysozyme from human monocytes in vitro. Indian J Exp Biol. 1991;29:910–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palsson-McDermott EM, O'Neill LA. Signal transduction by the lipopolysaccharide receptor, Toll-like receptor-4. Immunology. 2004;113:153–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polomano RC, Mannes AJ, Clark US, Bennett GJ. A painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat produced by the chemotherapeutic drug, paclitaxel. Pain. 2001;94:293–304. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rowinsky EK, Chaudhry V, Forastiere AA, Sartorius SE, Ettinger DS, Grochow LB, Lubejko BG, Cornblath DR, Donehower RC. Phase I and pharmacologic study of paclitaxel and cisplatin with granulocyte colony-stimulating fator: Neuromuscular toxicity is dose-limiting. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:2010–2020. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shibasaki M, Sasaki M, Miura M, Mizukoshi K, Ueno H, Hashimoto S, Tanaka Y, Amaya F. Induction of high mobility group box-1 in dorsal root ganglion contributes to pain hypersensitivity after peripherl nerve injury. Pain. 2010;149:514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shubayev VI, Myers RR. Upregulation and interaction of TNFa and gelatinases A and B in painful peripheral nerve injury. Brain Res. 2000;855:83–89. 2–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siau C, Xiao W, Bennett GJ. Paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked painful peripheral neuropathies: Loss of epidermal innervation and activation of Langerhans cells. Exp Neurol. 2006 Jun 21;201:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sommer C, Lindenlaub T, Teuteberg P, Schafers M, Hartung T, Toyka KV. Anti-TNF-antibodies reduce pain-related behavior in two different mouse models of painful mononeuropathy. Brain Res. 2001;913:86–89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02743-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sommer C, Marziniak M, Myers RR. The effect of thalidomide treatment on vascular pathology and hyperalgesia caused by chronic constriction injury of rat nerve. Pain. 1998;74:83–91. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sommer C, Schafer M, Marziniak M, Toyka KV. Etanercept reduces hyperalgesia in experimental painful neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2001;6:67–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2001.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sommer C, Schmidt C, George A. Hyperalgesia in experimental neuropathy is dependent on the TNF receptor 1. Exp Neurol. 1998;151:138–142. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sorge RE, Lacroix-Fralish ML, Tuttle AH, Sotocinal SG, Austin JS, Ritchie J, Chanda ML, Graham AC, Topham L, Beggs S, Salter MW, Mogil JS. Spinal cord Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity in male but not female mice. J Neurosci. 2011 Oct 26;31:15450–15454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3859-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sorkin LS, Doom CM. Epineurial application of TNF elicits an acute mechanical hyperalgesia in the awake rat. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2000;5:96–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2000.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sweitzer SM, Colburn RW, Rutkowski M, DeLeo JA. Acute peripheral inflammation induces moderate glial activation and spinal IL-1b expression that correlates with pain behavior in the rat. Brain Res. 1999;829:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanga FY, Nutile-McMenemy N, DeLeo JA. The CNS role of Toll-like receptor 4 in innate neuroimmunity and painful neuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Apr 19;102:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501634102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsoyi K, Jang HJ, Nizamutdinova IT, Kim YM, Lee YS, Kim HJ, Seo HG, Lee JH, Chang KC. Metformin inhibits HMGB1 release in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells and increases survival rate of endotoxaemic mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1498–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vallejo R, Tilley DM, Vogel L, Benyamin R. The role of glia and the immune system in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain. Pain Pract. 2010;10:167–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wadachi R, Hargreaves KM. Trigeminal nociceptors express TLR-4 and CD14: a mechanism for pain due to infection. J Dental Res. 2006;85:49–53. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watanabe T, Nagase K, Chosa M, Tobinai K. Schwann cell autophagy induced by SAHA, 17-AAG, or clonazepam can reduce bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy. Brit J Cancer. 2010;103:1580–1587. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weintraub M, Adde MA, Venzon DJ, Shad AT, Horak ID, Neely JE, Seibel NL, Gootenberg J, Arndt C, Nieder ML, Magrath IT. Severe atypical neuropathy associated with administration of hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors and vincristine. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:935–940. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woolf CJ, Allchorne A, Safieh-Garabedian B, Poole S. Cytokines, nerve growth factor and inflammatory hyperalgesia: the contribution of tumor necrosis factor a. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:417–424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoon S-Y, Robinson CR, Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Gap junction protein connexin 43 is involved in the induction of oxaliplatin-related neuropathic pain. J Pain. 2013;14:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zaks-Zilberman M, Zaks TZ, Vogel SN. Induction of proinflammatory and chemokine genes by lipopolysaccharide and paclitaxel (Taxol) in murine and human breast cancer cell lines. Cytokine. 2001 Aug 7;15:156–165. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang H, Boyette-Davis JA, Kosturakis A, Li Y, Yoon SY, Walters ET, Dougherty PM. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and its receptor CCR2 in primary sensory neurons contributes to paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Pain. 2013;14:1031–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang H, Mei X, Zhang P, Ma C, White FA, Donnelly DF, LaMotte RH. Altered functional properties of satellite glial cells in compressed spinal ganglia. GLIA. 2009 Nov 15;57:1588–1599. doi: 10.1002/glia.20872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang H, Yoon S-Y, Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Evidence that spinal astrocytes but not microglia contribute to the pathogenesis of paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy. J Pain. 2012;13:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zheng FY, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. The response of spinal microglia to chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathies is distinct from that evoked by traumatic nerve injuries. Neuroscience. 2011 Mar 10;176:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]