Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative bacterium that opportunistically infects critically ill hospitalized patients with breaches in skin integrity and airway protection, leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Considering the paucity of well-established animal models of immunosuppression to study A. baumannii pathogenesis, we set out to characterize a murine model of immunosuppression using the alkylating agent cyclophosphamide (CYP). We hypothesized that CYP-induced immunosuppression would increase the susceptibility of C57BL/6 mice to developing A. baumannii-mediated pneumonia followed by systemic disease. We demonstrated that CYP intensified A. baumannii-mediated pulmonary disease, abrogated normal immune cell function and led to altered pro-inflammatory cytokine release. The development of an animal model that mimics A. baumannii infection onset in immunosuppressed individuals is crucial for generating novel approaches to patient care and improving public health strategies to decrease exposure to infection for individuals at risk.

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative coccobacillus that has emerged as one of the most problematic causative agents of hospital-related infections in the world. The current clinical manifestations of A. baumannii infections include diverse nosocomial illnesses, such as intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired pneumonia (Gaynes & Edwards, 2005), bloodstream infection (Wisplinghoff et al., 2004), urinary tract infection (Gaynes & Edwards, 2005), meningitis (Metan et al., 2007) and, in occasional cases, endocarditis (Olut & Erkek, 2005). Additionally, the microbe is responsible for the majority of community-acquired pneumonia cases in certain tropical climates (Anstey et al., 2002; Leung et al., 2006). Importantly, A. baumannii’s prominence is due to its association with infected traumatic wounds acquired in battlefield and natural disaster conditions (Johnson et al., 2007; Murray et al., 2006; Petersen et al., 2007). To exacerbate the problem, A. baumannii is intrinsically resistant to a number of commonly used antibiotics.

Moreover, there is significant morbidity and mortality associated with this opportunistic microbe. In the USA, A. baumannii ICU-acquired pneumonia is usually encountered in 5–10 % of patients receiving mechanical ventilation (Gaynes & Edwards, 2005). More than 35 % of ICU patients with bloodstream infections die (Wisplinghoff et al., 2004). Moreover, both ICU-related conditions typically have late onsets after prolonged hospitalization and prior antibiotic exposure. Mortality from post-neurosurgical A. baumannii meningitis in patients with external ventricular shunts may be as high as 70 % (Metan et al., 2007). Community-acquired pneumonia affects alcoholics in tropical regions primarily during the rainy season, frequently leads to systemic infection and has a mortality rate of ~50 % (Leung et al., 2006). The organism causes 2.1 % of ICU-acquired skin/soft tissue infections (Gaynes & Edwards, 2005) and was isolated from >30 % of combat victims with open tibial fractures in Iraq and Afghanistan (Johnson et al., 2007).

Cyclophosphamide (CYP) is a cytotoxic alkylating agent widely used for the treatment of neoplastic and severe autoimmune diseases. CYP has been reported to reduce or augment a wide variety of immune responses. For instance, CYP suppresses myelopoiesis resulting in neutrophil depletion in murine models (Zuluaga et al., 2006). Moreover, CYP inhibits a suppressor response that normally prevents activation of effector T cells (Yasunami & Bach, 1988). The exacerbation of inflammatory responses and blockade of suppressive activity after CYP treatment is consistent with the suggestion that CYP preferentially depletes suppressor or regulatory T cells (Ghiringhelli et al., 2004; Yasunami & Bach, 1988).

A. baumannii is an extremely successful opportunistic pathogen of immunosuppressed individuals. Currently there is a lack of well-established animal models of immunosuppression to study its pathogenesis. The objective of the present study was to characterize a murine model of impaired immunity using CYP in order to mimic the opportunistic behaviour of A. baumannii in a hospital setting. We hypothesized that CYP-induced immunosuppression would increase animals’ susceptibility to A. baumannii-mediated pneumonia followed by systemic disease. Finally, we documented the effect of this alkylating agent on the antimicrobial function of phagocytic cells during A. baumannii infection.

Methods

Acinetobacter baumannii.

A. baumannii 0057, a clinical isolate acquired from Mark D. Adams (Cleveland, OH), was chosen for this study because it has been sequenced and it is resistant to multiple antibiotics, including carbapenem, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol and penicillin, which are commonly used to treat Gram-negative infections (Adams et al., 2008; Falagas et al., 2006). The strain was isolated in 2004 from a soldier’s blood culture at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington DC, USA. The strain was stored at −80 °C in brain heart infusion broth (Becton Dickinson) with 40 % glycerol until use. Test organisms were grown in a tryptic soy broth (MP Biomedicals) overnight at 37 °C using a rotary shaker set at 150 r.p.m. Growth was monitored by measuring OD600 (Bio-Tek). A. baumannii 0057 is available to the scientific community on request to the corresponding author.

CYP administration and infection.

All animal studies were conducted according to the experimental practices and standards approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Long Island University. To investigate the immunosuppressive effects of CYP in A. baumannii pneumonia, a single dose of 300 mg kg−1 CYP (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was administered intraperitoneally to female C57BL/6 mice (age, 6–8 weeks; Charles Rivers) 3 days before infection. PBS was similarly injected intraperitoneally into control mice before infection. To assess survival rates, infection was induced by anaesthetization [100 mg kg−1 ketamine (Keta-set), 10 mg kg−1 xylazine (Anased)] and intranasal inoculation with 3.75×106, 5×106 or 107 A. baumannii cells. For other studies, sublethal infection was performed by intranasal inoculation of 3.75×106 A. baumannii cells. Animals were killed humanely at days 3 and 7, and lung tissues were excised for histology, c.f.u. determinations and cytokine production. Uninfected CYP- and PBS-treated mice were used as controls.

Colony count determinations in tissues.

At days 3 and 7 post-infection, mouse tissues (lungs, liver and kidney) were excised and homogenized in sterile PBS. Serial dilutions of homogenates were made; a 100 µl suspension of each sample was then plated on tryptic soy agar (MP Biomedicals) plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Quantification of viable bacterial cells was determined by c.f.u. counts and the results were normalized by tissue weights.

Histological processing.

At days 3 and 7 post-infection, wound tissues were excised from humanely killed mice; the tissues were fixed in 10 % formalin and embedded in paraffin. Vertical sections (4 μm) were cut, and then fixed to glass slides and subjected to haematoxylin and eosin Gram staining to assess morphology and presence of bacteria, and immunohistochemistry for myeloperoxidase (MPO) or F4/80 to detect neutrophil or macrophage infiltration, respectively. The slides were examined using an Axiovert 40CFL inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss) and images were captured with an AxioCam MRc digital camera using the Zen 2011 digital imaging software.

J774.16 macrophage-like cells.

The J774.16 macrophage cell line originated from a murine reticulum cell sarcoma and has been extensively used to study microbe–macrophage interactions (American Type Culture Collection). The J774.16 cells were stored at −80 °C prior to use. The J774.16 cells were suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10 % heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 10 % NCTC-109 (Gibco Laboratories, Life Technologies) and 1 % non-essential amino acids (Cellgro; Mediatech), passaged three to four times, and grown as confluent monolayers on tissue culture plates prior to each experiment.

Phagocytosis assay.

Phagocytosis was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. J774.16 macrophages (106 cells) were incubated on six-well plates (3 ml per well) with CYP (12.5 or 25 µmol l−1; Sigma) or PBS for 2 h at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. A. baumannii cells labelled with FITC (Molecular Probes) were incubated with 25 % mouse serum (Sigma) for 30 min to allow complement proteins to opsonize A. baumannii. Bacterial cells were washed and then 107 bacterial cells were added to J774.16 cells for 2 h. Samples were processed on an LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Biosciences) and were analysed using FlowJo software.

A. baumannii killing assay.

J774.16 and A. baumannii cell interaction assays were performed as described in the phagocytosis assay protocol. Quantification of viable bacteria was determined at 18 h by measuring c.f.u. after macrophages had been lysed by forcibly passing the culture through a 27-gauge needle 5–7 times. Four microtitre wells per experimental condition were used to ascertain c.f.u. For each well, serial dilutions were plated in triplicate onto tryptic soy agar plates, which were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Nitric oxide determinations.

Nitric oxide (NO) produced in supernatants by untreated or CYP-treated macrophages was quantified after exposure to A. baumannii using a Griess method kit (Promega).

Cytokine determinations.

Three mice per group were killed humanely at days 3 and 7 post-infection. The right lung of each mouse was excised and homogenized in PBS with protease inhibitors (Complete Mini). Cell debris was removed from homogenates by centrifugation at 6000 g for 10 min to remove cell debris. Samples were stored at −80 °C until tested. Supernatants were tested for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 by ELISA (Becton Dickinson). The limits of detection were 31.3 pg ml−1 for IFN-γ and 15.6 pg ml−1 for TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analysed using Prism (GraphPad). Differences in survival rates were analysed by the log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). Analyses of colony counts, cell counts, killing assay, NO and cytokine data were done using ANOVA and adjusted by use of the Bonferroni correction. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

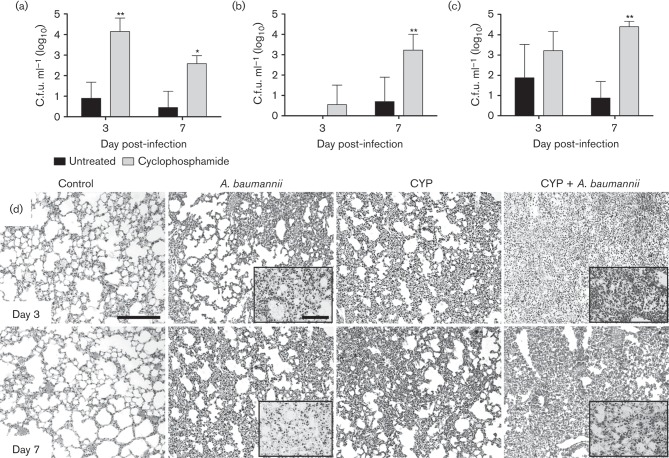

CYP-treated mice display reduced survival in A. baumannii infection

In order to develop an animal model of immunosuppression to study the opportunistic nature and progression of A. baumannii pathogenesis, we injected C57BL/6 mice with a single dose of 300 mg kg−1 CYP followed by microbial infection with sublethal inocula. Sublethal inocula were used with the objective of identifying the lowest bacterial load necessary to study disease progression for prolonged periods of time since previous studies in our laboratory have shown that intranasal infections of 107 A. baumannii 0057 cells in healthy mice are mostly cleared by the animal’s immune system within 72 h. Our findings indicate that CYP accelerated the death of mice infected with 5×106 or 107 c.f.u. A. baumannii cells compared to mice infected with 3.75×106 cells (P<0.01; Fig. 1). At 96 and 120 h post-infection, 100 % of CYP-treated mice infected with 5×106 and 107 A. baumannii cells died. In contrast, only 20 % of the CYP-treated mice infected with the lowest inoculum (3.75×106) died. On average, CYP-treated mice infected with 5×106 and 107 A. baumannii cells died of A. baumannii-mediated pneumonia at 96 and 78 h post-infection (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CYP administration reduces survival in C57BL/6 mice after A. baumannii sublethal intranasal infections. Survival differences of CYP C57BL/6 mice after infection with 3.75×106, 5×106 or 107 A. baumannii cells (n = 5 per group). Asterisks denote P-value significance (*P<0.01) calculated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) analysis. This experiment was performed twice and similar results were obtained.

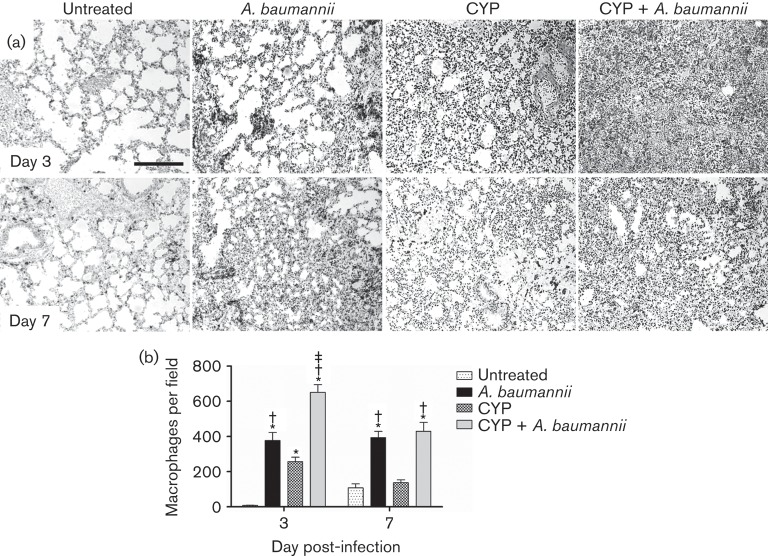

CYP exacerbates A. baumannii-mediated pneumonia in vivo

In sublethally infected mice, the pulmonary bacterial burden of CYP-treated animals was significantly higher than of untreated mice 3 (P<0.05) and 7 (P<0.01) days post-infection (Fig. 2a). We monitored whether CYP enhances A. baumannii dissemination from the lungs to the liver and kidneys. A. baumannii disseminated significantly from the lungs of CYP-treated mice to the liver (P<0.01; Fig. 2b) and kidneys (P<0.01; Fig. 2c) 7 days after infection. Histological examination revealed that untreated A. baumannii-infected and CYP-treated uninfected mice had moderate inflammation on days 3 and 7 (Fig. 2d). After infection, CYP-treated mice exhibited significant peribronchial inflammation and inflammatory cells were present within the alveoli (Fig. 2d). Gram staining showed a higher number of Gram-negative bacteria within the alveolar spaces of the lungs of infected mice treated with CYP than those of untreated controls on days 3 and 7 (Fig. 2d; insets). Untreated uninfected mice showed minimal recruitment and normal alveolar spaces. These studies demonstrated that CYP administration enhances disease progression by increasing pulmonary A. baumannii burden as shown in the colony count data.

Fig. 2.

CYP exacerbates A. baumannii-mediated pneumonia in vivo. Bacterial burden (c.f.u.) in (a) lungs, (b) liver and (c) kidneys excised from untreated and CYP-treated mice, infected with 3.75×106 A. baumannii cells (n = 5 per group) at 3 and 7 days post-infection. Asterisks denote P-value significance (*P<0.05 or **P<0.01) calculated by ANOVA and adjusted by use of the Bonferroni correction. This experiment was performed twice and similar results were obtained. (d) Histological analysis of lungs removed from untreated and uninfected (Control), untreated infected (A. baumannii), CYP-treated, uninfected (CYP) and CYP-treated, infected (CYP + A. baumannii) C57BL/6 mice. Representative haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of the lungs are shown with insets showing the Gram-negative A. baumannii. Bars, 10 µm.

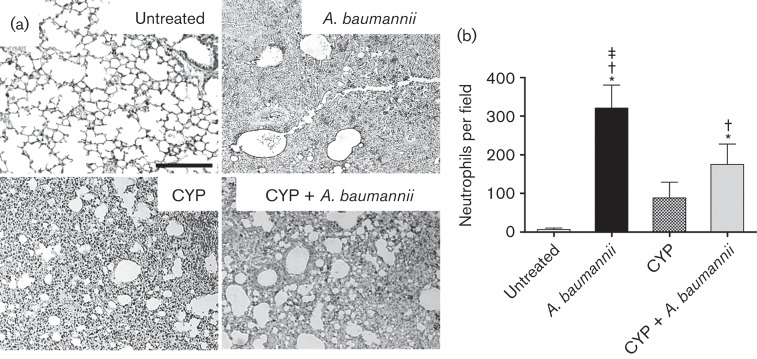

CYP administration and A. baumannii infection reduces neutrophil infiltration

We investigated the effect of CYP on neutrophil migration to the lungs (Fig. 3). First, neutrophil infiltration was evaluated by measuring the production of MPO in the pulmonary tissue. MPO is an enzyme present in abundant quantities within neutrophils. Three days post-infection, the localized dark staining indicated more neutrophil infiltration in uninfected and CYP-treated infected mice compared to untreated groups (Fig. 3a). However, CYP-treated infected mice showed considerably less MPO staining than untreated infected mice in the pulmonary tissue. Our quantitative analysis confirmed the presence of fewer neutrophils in the lungs of uninfected mice per field when compared to tissues of A. baumannii-infected mice (P<0.01) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

CYP decreases neutrophil infiltration in the lungs. (a) Histological analysis of untreated, A. baumannii, CYP and CYP + A. baumannii lungs excised from C57BL/6 mice, day 3. The dark staining indicates neutrophil infiltration. Representative MPO-immunostained sections of pulmonary tissue are shown. Bars, 10 µm. (b) Number of neutrophils per field in lung tissue of untreated, A. baumannii, CYP and CYP + A. baumannii mice. Solid bars are the mean numbers of neutrophils in 15 different fields, and error bars signify sd. *, † and ‡ indicate greater numbers of neutrophils than untreated, CYP and CYP + A. baumannii groups, respectively. Asterisks represent P-value significance (P<0.01) calculated by ANOVA and adjusted by use of the Bonferroni correction.

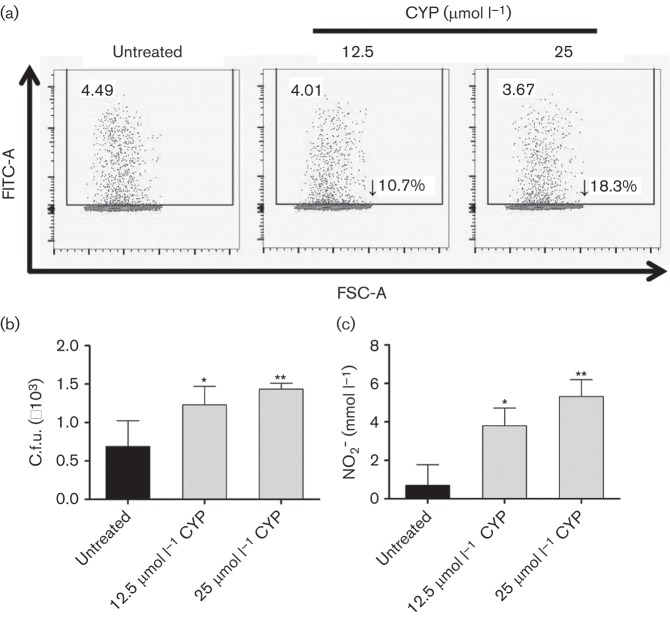

CYP and A. baumannii infection increases pulmonary macrophage infiltration

We identified macrophage infiltration by measuring the expression of F4/80, which is a marker typically expressed and upregulated during the activation of these cells. On day 3 post-infection, tissue sections from untreated murine lungs displayed clear alveolar spaces and minimal macrophage recruitment. CYP-treated infected mice showed a more massive macrophage infiltration to the lung area than infected or CYP-treated uninfected groups (Fig. 4a). The histological results were confirmed quantitatively: CYP-treated infected mice showed significantly higher numbers of macrophage had migrated to the lungs when compared to untreated (P<0.01), infected (P<0.01) or CYP-treated mice (P<0.01) (Fig. 4b). On day 7 post-infection, similar F4/80 staining was observed in the untreated and treated A. baumannii-infected groups (Fig. 4a). Uninfected groups demonstrated less macrophage infiltration in a scattered pattern when compared to A. baumannii-infected groups. The qualitative results were again quantitatively confirmed by macrophage counts (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

CYP administration and A. baumannii infection increases pulmonary macrophage infiltration. (a) Histological analysis of untreated, A. baumannii, CYP and CYP + A. baumannii lungs excised from humanely killed C57BL/6 mice, days 3 and 7. The dark staining indicates macrophage infiltration. Representative F4/80-immunostained sections of the lungs are shown. Bars, 10 µm. (b) Number of macrophages per field in pulmonary tissue of untreated, A. baumannii, CYP and CYP + A. baumannii mice. Solid bars are the mean numbers of macrophages in 15 different fields, and error bars denote sd. *, † and ‡ indicate greater number of neutrophils than untreated, CYP and CYP + A. baumannii groups, respectively. Asterisks denote P-value significance (P<0.01) calculated by ANOVA and adjusted by use of the Bonferroni correction.

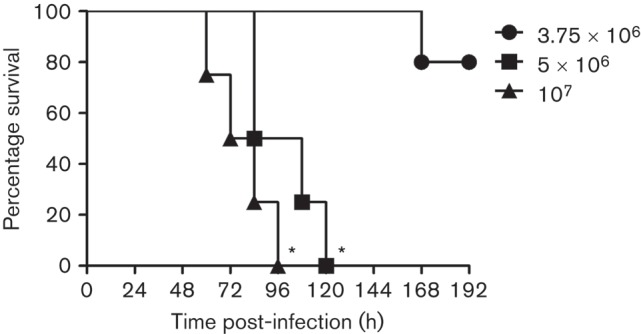

CYP alters phagocytosis and killing of A. baumannii by J774.16 cells

We analysed the effects of physiological CYP on A. baumannii phagocytosis and killing by J774.16 macrophage-like cells using FACS analysis. CYP reduced phagocytosis of A. baumannii by macrophages moderately, compared with the control (Fig. 5a). Our results show a 10.7 % and 18.3 % phagocytosis inhibition in cells treated with 12.5 and 25 µmol l−1 CYP, respectively, when compared to control cells.

Fig. 5.

CYP reduces J774.16 macrophage-cell like phagocytosis, NO production and killing of A. baumannii. J774.16 cells were untreated or exposed to CYP for 2 h followed by incubation with A. baumannii. (a) Phagocytosis of FITC-labelled A. baumannii by macrophages was determined using FACS analysis. FSC-A, forward scatter. (b) Killing of A. baumannii by J774.16 cells was determined using c.f.u. analysis. (c) NO production was quantified using the Griess method after untreated or CYP-treated macrophages were co-incubated with A. baumannii. For (b) and (c), error bars denote sd. Asterisks denote P-value significance (*P<0.05; **P<0.001) calculated by ANOVA and adjusted by use of the Bonferroni correction. These experiments were performed twice and similar results were obtained.

We examined whether CYP interferes with macrophage-mediated killing of A. baumannii. CYP significantly reduced bacterial killing by J774.16 cells (P<0.05) (Fig. 5b). Consequently, we investigated the impact of CYP on extracellular NO production by these macrophages after co-incubation with A. baumannii. Our results indicate that NO levels were significantly increased in the supernatants of CYP-treated cells (12.5 µmol l−1; P<0.05 and 25 µmol l−1; P<0.001) when compared to controls (Fig. c).

CYP administration increases host cytokine expression

We measured the pro-inflammatory cytokine response (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β and IL-6) in the lungs of untreated or CYP-treated mice that were uninfected or infected with A. baumannii (Table 1). On day 3, the pulmonary tissue of infected CYP-treated mice contained significantly higher quantities of IFN-γ (P<0.05), TNF-α (P<0.05) and IL-1β (P<0.05) than in other groups; IL-6 levels were similar. The untreated infected group displayed significantly higher levels of IFN-γ (P<0.05) than untreated controls. CYP-treated mice showed higher levels of IFN-γ (P<0.05), TNF-α (P<0.05) and IL-1β (P<0.05) than untreated mice. On day 7, the lungs of infected CYP-treated mice contained significantly lower levels of IFN-γ (P<0.05) and IL-1β (P<0.05) compared to the other groups. Untreated A. baumannii-infected mice exhibited significant increases in TNF-α (P<0.05), IL-1β (P<0.05) and IL-6 levels compared to untreated controls. In contrast, untreated infected mice showed lower levels of TNF-α (P<0.05) than untreated controls. In addition, significant increases in TNF-α (P<0.05) production and reduced IL-1β (P<0.05) and IL-6 (P<0.05) production were observed in CYP-treated mice compared to the untreated controls. Lastly, the infected CYP-treated group produced more IL-6 than the CYP-treated group and less than the infected untreated group (P<0.05).

Table 1. Cytokine levels in the lungs of C57BL/6 mice.

| Cytokine levels (pg ml−1) (mean±sem) | ||||||||

| Day 3 | Day 7 | |||||||

| IFN-γ | TNF-α | IL-1β | IL-6 | IFN-γ | TNF-α | IL-1β | IL-6 | |

| Untreated | 232.58±8.32 | 190.26±7.62 | 251.26±5.17 | 260.36±6.17 | 828.93±9.26 | 697.96±12.36 | 586.39±8.93 | 306.65±7.58 |

| A. baumannii | 453.08±5.48* | 138.62±4.04 | 384.08±2.41 | 343.65±3.66 | 1191.17±8.92* | 366.67±10.25§, † | 1307.49±14.36* | 677.01±6.99*,‡ |

| CYP | 599.21±2.65* | 382.36±5.89* | 1223.36±6.32* | 350.98±2.98 | 670.12±7.18 | 1221.82±11.63* | 365.94±15.08§, || | 173.4±7.35§ |

| CYP+A. baumannii | 1581.09±2.15*,†,‡ | 512.88±5.81*,†,‡ | 1462.59±3.03*,† | 357.59±4.58 | 391.99±10.29§, ||, # | 878.42±12.70† | 165.62±9.05§, || | 398.7±9.74‡, || |

, †, ‡ indicate higher levels than untreated, A .baumannii, and CYP groups, respectively.

, ||, # indicate lower levels than untreated, A. baumannii, and CYP groups, respectively.

Discussion

Although CYP, a well-described immunosuppressant, has been previously used to test the efficacy of single and combined antibiotic therapy against A. baumannii infection in an immunosuppressed mouse model (Song et al., 2009), the immune response against A. baumannii in this model has not been extensively characterized. In this study, we demonstrated that CYP administration had a profound effect on survival in mice which had been intranasally challenged with sublethal (5×106 and 107) A. baumannii inocula. These data may be useful in future investigations to gain insight into the efficacy of antimicrobial drugs or passive administration in the setting of impaired immunity, realistically mimicking clinical scenarios. Interestingly, phagocytic cells could be isolated from CYP-treated animals to study host–pathogen interactions to elucidate leukocyte function and the specific cellular cytokine profile during impaired immunity.

The increased mortality in CYP-treated mice was attributable to defective microbial clearance by immune cells. We observed a significant increase in bacterial burden and cellular recruitment in the lungs of CYP-treated animals compared to controls. After infection, A. baumannii-infected and CYP-treated mice had similar inflammation and inflammatory cells present within the alveoli, suggesting that increased A. baumannii burden and reduced animal survival were not a consequence of diminished recruitment of immune cells to the lungs. Both phenomena could be explained by decreased cellular microbicidal capacity, the type of cellular infiltration combating the infection or both.

The increased mortality in CYP-treated mice may be related to the reduction in the number of neutrophils. CYP-treated animals experienced a considerable reduction in recruitment of neutrophils to the lungs post-infection when compared to the untreated-infected group, as shown by MPO immunohistochemistry. Supporting the immunohistochemistry results, quantitative analysis showed a significant decrease in MPO production in the pulmonary tissue of CYP-treated animals. CYP causes significant changes in the numbers and composition of circulating neutrophils (Zimecki et al., 2010), therefore impairing resolution of bacterial infections by the host.

Macrophages participate in the early inflammatory responses and host defence against A. baumannii infection (Qiu et al., 2012). F4/80 immunohistochemistry showed an increase in macrophage recruitment in mice treated with CYP, suggesting that the massive infiltration of these phagocytic cells compensates for the reduction of neutrophils early during infection. The massive macrophage infiltration might be explained by the high levels of pro-inflammatory IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1β present in the pulmonary tissue of CYP-treated mice on day 3 post-infection. However, as A. baumannii disease progresses, CYP-treated animals displayed a significant reduction in the numbers of macrophages recruited to the infection site, even in the presence of high levels of TNF-α in the lungs. An increase in TNF-α levels might be attributed to a combined LPS-induced production by macrophages and lymphocytes recruited to the pulmonary tissue and not to IFN-γ priming as this pro-inflammatory cytokine was significantly reduced in infected CYP-treated mice. In contrast, immune-competent animals infected with A. baumannii produced high levels of IFN-γ, IL-1β and IL-6 and lower levels of TNF-α, and were, therefore, able to control the infection by modulating a balanced immune response.

Our findings suggest that CYP impairs the ability of macrophages to engulf and kill A. baumannii within the lungs (Hunninghake & Fauci, 1977) resulting in dissemination of infection to the bloodstream and other organs. We observed that A. baumannii phagocytosis was moderately reduced. After phagocytosis, bacteria are rapidly exposed to the microbicidal armamentarium of the macrophages, which consists of toxic reactive species (NO and lysosomal hydrolases). Our data show that NO generation is significantly increased in J774.16 cells that are exposed to CYP. In this regard, reduction of neutrophils by CYP stimulates massive recruitment of macrophages to the infection site increasing the probability of tissue damage by high production of NO. This observation is supported by an increase in TNF-α and suppression of IL-1β (Guo et al., 2002), which may be relevant in the activation of the inducible NO synthase, the enzyme responsible for NO production. At the cellular level, CYP might create an ideal environment for A. baumannii survival, facilitating intracellular replication and regulation of the phagolysosomal milieu.

In conclusion, this is the first report that demonstrates the impact of CYP on immunity in A. baumannii infection. This study describes a CYP-induced murine model of immunosuppression that may provide novel insights in the opportunistic nature of this microbe. The study of A. baumannii’s virulence mechanisms and host interactions is necessary to develop better public health strategies to decrease the incidence of hospital-related pneumonia for individuals at risk as well as generate novel approaches to patient care.

Acknowledgements

L. R. M. is supported by the National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases 5K22A1087817-02 and Long Island University-Post Faculty Research Committee awards. We acknowledge David Sanchez for his assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations:

- CYP

cyclophosphamide

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

References

- Adams M. D., Goglin K., Molyneaux N., Hujer K. M., Lavender H., Jamison J. J., MacDonald I. J., Martin K. M., Russo T. & other authors (2008). Comparative genome sequence analysis of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol 190, 8053–8064 10.1128/JB.00834-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstey N. M., Currie B. J., Hassell M., Palmer D., Dwyer B., Seifert H. (2002). Community-acquired bacteremic Acinetobacter pneumonia in tropical Australia is caused by diverse strains of Acinetobacter baumannii, with carriage in the throat in at-risk groups. J Clin Microbiol 40, 685–686 10.1128/JCM.40.2.685-686.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falagas M. E., Koletsi P. K., Bliziotis I. A. (2006). The diversity of definitions of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and pandrug-resistant (PDR) Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol 55, 1619–1629 10.1099/jmm.0.46747-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiringhelli F., Larmonier N., Schmitt E., Parcellier A., Cathelin D., Garrido C., Chauffert B., Solary E., Bonnotte B., Martin F. (2004). CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress tumor immunity but are sensitive to cyclophosphamide which allows immunotherapy of established tumors to be curative. Eur J Immunol 34, 336–344 10.1002/eji.200324181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Zhang Z., Green K., Stanton R. C. (2002). Suppression of interleukin-1 beta-induced nitric oxide production in RINm5F cells by inhibition of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 41, 14726–14733 10.1021/bi026110v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunninghake G. W., Fauci A. S. (1977). Immunological reactivity of the lung. IV. Effect of cyclophosphamide on alveolar macrophage cytotoxic effector function. Clin Exp Immunol 27, 555–559 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. N., Burns T. C., Hayda R. A., Hospenthal D. R., Murray C. K. (2007). Infectious complications of open type III tibial fractures among combat casualties. Clin Infect Dis 45, 409–415 10.1086/520029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W. S., Chu C. M., Tsang K. Y., Lo F. H., Lo K. F., Ho P. L. (2006). Fulminant community-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia as a distinct clinical syndrome. Chest 129, 102–109 10.1378/chest.129.1.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metan G., Alp E., Aygen B., Sumerkan B. (2007). Acinetobacter baumannii meningitis in post-neurosurgical patients: clinical outcome and impact of carbapenem resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 60, 197–199 10.1093/jac/dkm181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. K., Yun H. C., Griffith M. E., Hospenthal D. R., Tong M. J. (2006). Acinetobacter infection: what was the true impact during the Vietnam conflict? Clin Infect Dis 43, 383–384 10.1086/505601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olut A. I., Erkek E. (2005). Early prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Acinetobacter baumannii: a case report and brief review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis 37, 919–921 10.1080/00365540500262567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen K., Riddle M. S., Danko J. R., Blazes D. L., Hayden R., Tasker S. A., Dunne J. R. (2007). Trauma-related infections in battlefield casualties from Iraq. Ann Surg 245, 803–811 10.1097/01.sla.0000251707.32332.c1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H., KuoLee R., Harris G., Van Rooijen N., Patel G. B., Chen W. (2012). Role of macrophages in early host resistance to respiratory Acinetobacter baumannii infection. PLoS ONE 7, e40019 10.1371/journal.pone.0040019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. Y., Cheong H. J., Lee J., Sung A. K., Kim W. J. (2009). Efficacy of monotherapy and combined antibiotic therapy for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia in an immunosuppressed mouse model. Int J Antimicrob Agents 33, 33–39 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein R. A., Gaynes R., Edwards J. R., National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (2005). Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis 41, 848–854 10.1086/421946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisplinghoff H., Bischoff T., Tallent S. M., Seifert H., Wenzel R. P., Edmond M. B. (2004). Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 39, 309–317 10.1086/421946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasunami R., Bach J. F. (1988). Anti-suppressor effect of cyclophosphamide on the development of spontaneous diabetes in NOD mice. Eur J Immunol 18, 481–484 10.1002/eji.1830180325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimecki M., Artym J., Kocieba M., Weber-Dabrowska B., Borysowski J., Górski A. (2010). Prophylactic effect of bacteriophages on mice subjected to chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression and bone marrow transplant upon infection with Staphylococcus aureus. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl) 199, 71–79 10.1007/s00430-009-0135-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuluaga A. F., Salazar B. E., Rodriguez C. A., Zapata A. X., Agudelo M., Vesga O. (2006). Neutropenia induced in outbred mice by a simplified low-dose cyclophosphamide regimen: characterization and applicability to diverse experimental models of infectious diseases. BMC Infect Dis 6, 55 10.1186/1471-2334-6-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]