Abstract

Background:

People with a strong sense of coherence (SOC) have a high ability to cope with stress and maintain good physical and mental health.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between depressive state, job stress, and SOC among nurses in a Japanese general hospital.

Materials and Methods:

A self-reporting survey was conducted among 348 female nurses in a general hospital. Job stress was measured using the Japanese version of the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) scale. Depressive state was assessed by the K6 scale. SOC was assessed with the SOC scale, which includes 29 items. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine factors that significantly affect depressive state.

Results:

SOC, over-commitment, effort-esteem ratio, and age were significantly correlated with the depressive state (β = −0.46, P < 0.001; β = 0.27, P < 0.001; β = 0.16, P < 0.001; β = −0.10, P < 0.001, respectively).

Conclusions:

SOC may have a major influence on the depressive state among female nurses in a Japanese general hospital. From a practical perspective, health care professionals should try to enhance the SOC of nurses.

Keywords: Depressive state, effort-reward imbalance over-commitment, sense of coherence

INTRODUCTION

The sense of coherence (SOC), which was proposed by Antonovsky[1] is based on the salutogenic model of health. The SOC is composed of three factors; (1) the stimuli derived from internal and external environments in the course of living are structured, predictable, and explicable (comprehensibility); (2) resources are available to meet the demands posed by these stimuli (manageability); and (3) such demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement (meaningfulness). Antonovsky[1] defined the SOC as a personality dimension that is hypothesized to influence stress recognition style, facilitate stress management, and contribute to overall well-being. People with a strong SOC have a high ability to cope with stress and maintain good physical and mental health.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

To the best of our knowledge, six studies have investigated the association between SOC, job stress, and mental health.[10,11,12,13,14,15] Findings from these studies suggest that SOC modified the effect of job stress on mental health.

To the best of our knowledge, only four studies have investigated the relationship between the SOC and depressive symptoms, one used the brief job stress questionnaire[15] and the other three used General Health Questionnaire.[10,12,13] These studies suggested that a weak SOC was a strong predictor of mental distress, including depressive symptoms.

Nurses are exposed to high-stress work environments, including irregular work schedules, shift work, and interaction with patients and other hospital staff members. Therefore, preventing mental distress, including depressive state, is an important issue for nurses. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between depressive state, job stress, and SOC among nurses in Japanese general hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In February 2013, supervisors distributed a questionnaire to all nurses (n = 710) in a general hospital with 611 beds in an urban area in Japan. Nurse specialties included intensive care, pediatrics, surgery, oncology, and emergency medicine. Management allowed nurses to complete the questionnaires during their shifts.

An explanation of the nature of the survey accompanied the questionnaire, which was anonymous and voluntary. Consent was assumed if participants answered and returned the questionnaire. The study was approved by both the local direction board and the committee for the prevention of physical disease and mental illness among health care workers at the general hospital.

The questionnaire collected data on age, hours of work (full-time or part-time), shift work, overtime hours per week, and job rank (manager, middle manager or staff nurse).

We measured job stress using the Japanese version of the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) scale (23 items) translated by Tsutsumi et al.[16] The ERI consists of three subscales; effort (6 items), reward (11 items) and over-commitment (6 items). The reward subscale is further divided into three subgroups: Esteem, job security, and promotion. The validity of this questionnaire has been confirmed.[17] The ERI model indicates that job stress is related to high effort with low reward. Four ERI ratios (ERI, effort-esteem imbalance, effort-promotion imbalance, and effort-job security imbalance) were calculated based on the total scores according to Tsutsumi et al.[16]

The SOC scale consisted of 29 items assessing comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. Scores for each item ranged from 1 to 7 points, and the total score was calculated as the SOC score. A higher score indicated a stronger SOC.

We measured depressive state using the K6 short screening questionnaire that was developed in accordance with the World Health Organization translation guidelines.[18] The K6 consists of six items on depression and anxiety, each of which is measured on a 5-point scale (0-4). Higher scores indicate a more depressive state. The K6 was translated into Japanese and showed good validity with the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, mood, and anxiety disorders in a community sample.[19]

We used Pearson's correlation to investigate the relationship among age, work related-factors, job stress, SOC, and depressive state. To examine factors with a significant effect on depressive state, stepwise multiple regression analyses were conducted with the K6 total score as the dependent variable and variables related to the depressive state as independent variables.

We used SPSS 11 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for all analyses. Significance was defined at the level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Completed questionnaires were returned by 420 out of 710 nurses (response rate, 59.2%). Male nurses were excluded from the analysis because only 28 of the 42 (66.7%) male nurses responded. Subjects with missing values for job stress, SOC, or depressive state were also excluded (n = 43). The final sample for analysis consisted of 348 female nurses (52.1%), including nurses who were managers and middle managers.

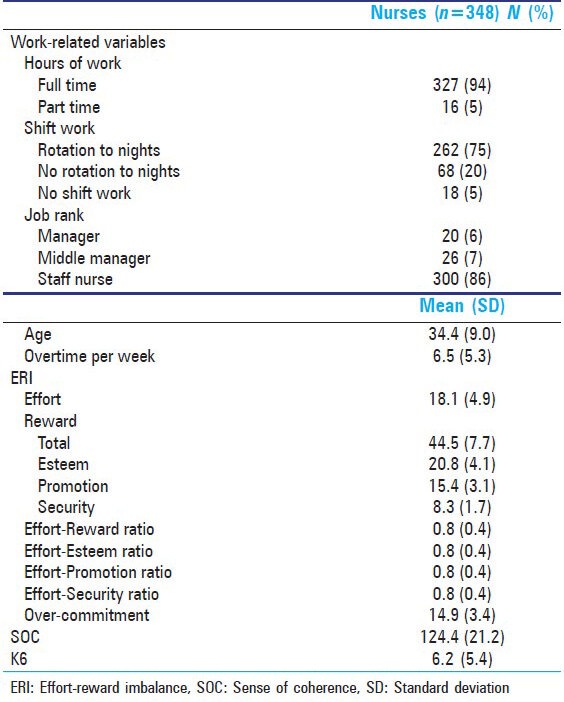

Overtime was reported in hours per week, which was voluntary but limited to 45 h/month. Shift work categories included: “No shift work,” “shift work with rotation to night shift,” or “shift work without rotation to night shift.” Only managers have a choice in shift assignment. Table 1 shows characteristics of study subjects.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects

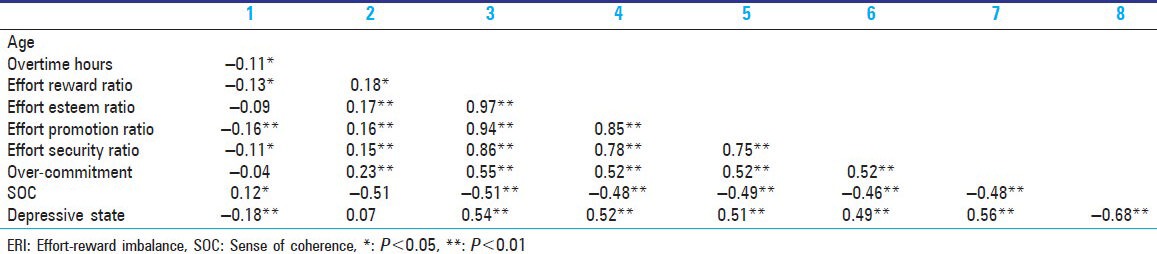

Table 2 shows the Pearson's correlation coefficients between age, overtime hours, ERI ratios, SOC, and the depressive state. Depressive state moderately correlated with three ERI ratios, over-commitment, and SOC.

Table 2.

Pearson's coreration between work environments, ERI ratios, over-commitment, SOC and depressive state

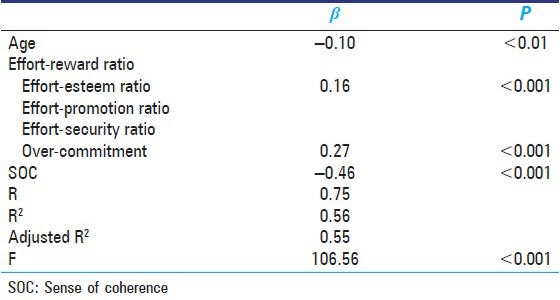

Table 3 shows the influence of work-related factors, ERI ratios, and SOC on depressive state. SOC, over-commitment, effort-esteem ratio, and age were significantly correlated with depressive state (β = −0.46, P < 0.001; β =0.27, P < 0.001; β =0.16, P < 0.001, β = −0.10, P < 0.01, respectively). The coefficient of multiple determination (R2) was 0.56 (F = 106.56 P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Stepwise multiple liner regression for depressive state

DISCUSSION

We found that SOC, over-commitment, effort-esteem ratio, and age were predictors of depressive state among female nurses in the general hospital. The SOC was inversely associated with depressive state, which was similar to previous studies.[10,12,13,15] The SOC had a major influence on depressive state [Table 3]. The present findings contribute to the literature investigating the relationship between depressive state, job stress, and SOC.

Strength of our study is that we investigated the independent contribution of three ratios of ERI (effort-esteem, effort-job security, and effort-promotion), over-commitment, and SOC to the depressive state. According to our previous study,[20] effort-promotion and over-commitment predicted a depressive state. The present findings suggest that a depressive state of nurses was associated with not only job stress but also both over-commitment and SOC.

Age correlated positively with SOC [Table 2], which was also similar to a previous study by Harri[21] who suggested that SOC tends to increase with age. Previous studies suggested that an increasing SOC of workers may reduce negative job stress responses and mental health problems.[13,15] Intervention support enhancing the SOC could be effective in preventing nurses from experiencing a depressive state.

The present study has some weaknesses. First, the sample size was small and included nurses from only one general hospital. A longitudinal study with a lager sample is necessary.

CONCLUSION

Our findings provide insight into some factors associated with a depressive state among nurses in a general hospital. From a practical perspective, the influence of SOC on a depressive state should be considered for health care professionals. Intervention support such as group cognitive psychotherapy to strengthen comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness may help nurses cope better with job stress and reduce their risk of depression.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonovsky A. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1987. Unraveling the mystery of health, how people manage stress and stay well. Translated into Japanese by Yamazaki Y and Yoshii K (2001), Yusindo Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agardh EE, Ahlbom A, Andersson T, Efendic S, Grill V, Hallqvist J, et al. Work stress and low sense of coherence is associated with type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Swedish women. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:719–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonsson A, Segesten K, Mattsson B. Post-traumatic stress among Swedish ambulance personnel. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:79–84. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kristenson M, Kucinskienë Z, Bergdahl B, Calkauskas H, Urmonas V, Orth-Gomér K. Increased psychosocial strain in Lithuanian versus Swedish men: The LiVicordia study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:277–82. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malinauskiene V, Leisyte P, Romualdas M, Kirtiklyte K. Associations between self-rated health and psychosocial conditions, lifestyle factors and health resources among hospital nurses in Lithuania. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:2383–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasermoaddeli A, Sekine M, Hamanishi S, Kagamimori S. Associations between sense of coherence and psychological work characteristics with changes in quality of life in Japanese civil servants: A 1-year follow-up study. Ind Health. 2003;41:236–41. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.41.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Runeson R, Norbäck D. Associations among sick building syndrome, psychosocial factors, and personality traits. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;100:747–59. doi: 10.2466/pms.100.3.747-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeuchi T, Yamazaki Y. Relationship between work-family conflict and a sense of coherence among Japanese registered nurses. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2010;7:158–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuomi K, Seitsamo J, Huuhtanen P. Stress management, aging, and disease. Exp Aging Res. 1999;25:353–8. doi: 10.1080/036107399243805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urakawa K, Yokoyama K. Sense of coherence (SOC) may reduce the effects of occupational stress on mental health status among Japanese factory workers. Ind Health. 2009;47:503–8. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.47.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, Klaghofer R. Chronic stress experience in young physicians: Impact of person- and workplace-related factors. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;83:373–9. doi: 10.1007/s00420-009-0467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haoka T, Sasahara S, Tomotsune Y, Yoshino S, Maeno T, Matsuzaki I. The effect of stress-related factors on mental health status among resident doctors in Japan. Med Educ. 2010;44:826–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malinauskiene V, Leisyte P, Malinauskas R. Psychosocial job characteristics, social support, and sense of coherence as determinants of mental health among nurses. Medicina (Kaunas) 2009;45:910–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogińska-Bulik N. The role of personal and social resources in preventing adverse health outcomes in employees of uniformed professions. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2005;18:233–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urakawa K, Yokoyama K, Itoh H. Sense of coherence is associated with reduced psychological responses to job stressors among Japanese factory workers. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:247. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsutsumi A, Ishitake T, Peter R, Siegrist J, Matoba T. The Japanese version of the effort-reward imbalance questionnaire: A study in dental technicians. Work Stress. 2001;15:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsustumi A, Kayaba K, Nagami M, Miki A, Kawano Y, Ohya Y, et al. The effort-reward imbalance model: Experience in Japanese working population. J Occup Health. 2002;44:398–407. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17:152–8. doi: 10.1002/mpr.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K, Yanagida K, Kawakami N. Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65:434–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikuchi Y, Nakaya M, Ikeda M, Narita K, Takeda M, Nishi M. Effort-reward imbalance and depressive state in nurses. Occup Med (Lond) 2010;60:231–3. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harri M. The sense of coherence among nurse educators in Finland. Nurse Educ Today. 1998;18:202–12. doi: 10.1016/s0260-6917(98)80080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]