Abstract

Background:

In Turkey, general practitioners were authorized to work as family physicians without specialization, within the scope of the Health Transformation Programme, due to inadequate number of family medicine specialists since 2004. With this new implementation Family Medicine specialty became a less preferable option for medical students.

Aims:

The study was to investigate the perspectives of medical students and understand the issues to choose Family Medicine specialty as a career option.

Materials and Methods:

This qualitative study was performed with 48 final year medical students using a convenience sample from two medical universities.

Results:

Three main categories emerged from the data viewing Family Medicine ‘as a specialty’, ‘as an employment’, and finally ‘as a system’. Very few students stated that Family Medicine would be their choice for specialty.

Conclusions:

Family Medicine does not seem to be an attractive option in career planning by medical students. Several factors that may constrain students from choosing Family Medicine include: not perceiving Family Medicine as a field of expertise, and the adverse conditions at work which may originate from duality in the system.

Keywords: Career, Choose, Family medicine, General practice, Specialty

Introduction

To implement high-quality primary care, an equal, qualified, and accessible health-care system is inevitable. Family Medicine (FM) specialists are certainly the most appropriate physicians to be positioned in primary care. However, the relatively low number of FM specialists is currently a prevalent problem all over the world.

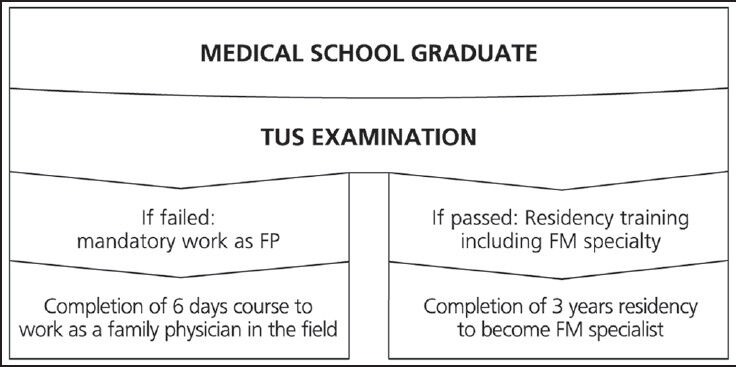

In Turkey, the only way to enter a specialty programme is to succeed in the Medical Specialty Examination (TUS) after graduation. TUS is a centralized multiple choice test that has been held biannually since 1986. The medical graduates are positioned by their TUS scores in the residencies that they have applied for. Each year, the score to enter a given specialty may change according to the popularity of that specialty among the graduates. Furthermore, these positions are restricted by the number of positions listed, especially in popular branches. Because of high number of graduates, and applications to TUS, some physicians may not be matched to any residency. Physicians who are not successful in obtaining their desired residency position may take TUS again, or they may complete their mandatory obligation and serve 1 year as a family physician (FP) in a rural area, more commonly being in the eastern part of Turkey [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Two different paths to become a family physician in Turkey

FM has been recognized as a field of specialization in Turkey for nearly 30 years.[1] Medical school graduates who want to pursue a career in FM specialty also were required to take TUS.[2] However, since 2004, the Ministry of Health (MoH) authorized the general practitioners (GPs) who were already working in the field to continue within the scope of the Health Transformation Programme (HTP). This was due to inadequate number of FM specialists. A standardized training model was put forward for GPs by the MoH, and the training was planned to be conducted in two phases. During the initial phase, medical graduates and GPs, working in the system, would attend orientation training for 1 week. The second planned phase is a 1-year modular training programme. Within this plan, the physicians who complete their first phase orientation training go onto the second longer term training phase.[3,4] During this time, and after signing a new contract, physicians begin working as FPs in their offices. Within the scope of the HTP, the MoH started a new process of restructuring the primary health care and has called it the “Family Medicine System.” As a consequence, this situation has caused confusion among the medical students about FM being “a discipline” or “a system.” Furthermore, these new policies and implementations also caused confusion among medical professionals.

Although some of the factors that influenced medical students’ career choices had been reported from Turkey, our research is the first to use a qualitative methodology to understand the motivating factors of medical students in their final year to become FPs. In this study, our aim was to explore the perspectives of medical students and understand the motivating or demotivating issues.

Materials and Methods

All participants consented to be interviewed, and the Yeditepe University Ethical Board approved the study. The study was performed from January to April 2013.

This qualitative study was conducted in two medical universities, with a total of 48 final-year students, using a convenience sample. Focus group discussions were held, each including six to nine students. Three focus groups were performed in a private foundation university (with 92 final-year students), whereas another three were held in a state university (with 145 final-year students).

Students were invited to participate in the discussions, which were requested by the principal investigator. One moderator and one observer, who were previously trained, worked during these focus group sessions. The sessions lasted between 45-60 minutes and were recorded digitally (audio only) with permission from the participants.

Setting

This study was conducted in Istanbul, a densely populated city of Turkey. In Istanbul, there are nine foundation (private) medical universities and three government (state) medical universities that receive students from all over Turkey for medical training. In the Yeditepe University Faculty of Medicine, medical students have rural medicine clerkship during their final year, which consists of 2 weeks spent at the campus with theoretical lectures on the fundamentals of family practice and four weeks spent with a practicing FP. At the Marmara University Medical Faculty, the students do not undergo FM clerkship in their final year; they visit family health units in their second and third year when they also have theoretical lectures in FM.

Participants

Twenty male and 28 female students participated in the focus groups. The mean age was 24.45 ± 1.08 (range, 23-27). Six students’ parents were physicians, whereas 11 students had close relatives who were physicians.

Data collection

After a literature review, questions were determined by the consensus of the researchers. The questions included are as follows: “What are your opinions about family medicine?” “Do you consider FM as a specialty option?” and “How did your medical school training influence your perspectives in FM?” Data saturation was reached following the fifth focus group.

Statistical analysis

After each focus group, the recordings were listened to, transcribed, and correlated with the notes that interviewers had taken during the focus groups. Each focus group transcript was read separately and during a meeting to form a coding structure. Four investigators read, identified, and assigned codes for the major themes of the data. These codes were assigned to lines of text, and then, a word processing program was used in the data analysis by recalling relevant codes from the text. In our study, we used “phenomenological approach and thematic analysis.”

Results

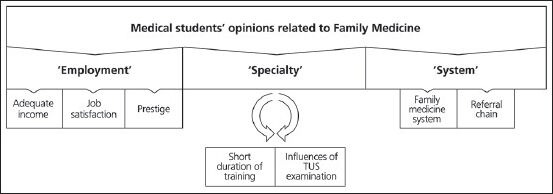

Three main headings emerged from the data regarding the participants’ views about “family medicine”: initially, “as a specialty,” then “as an employment,” and finally, “as a system” [Figure 2]. A very scarce number of students stated that FM would be among their choices for specialty. The most favorable example for choosing to become an FP was the guaranteed employment by the government after graduation without a need for specialization. Key themes influencing to choose FM are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework regarding medical students’ opinions related to FM

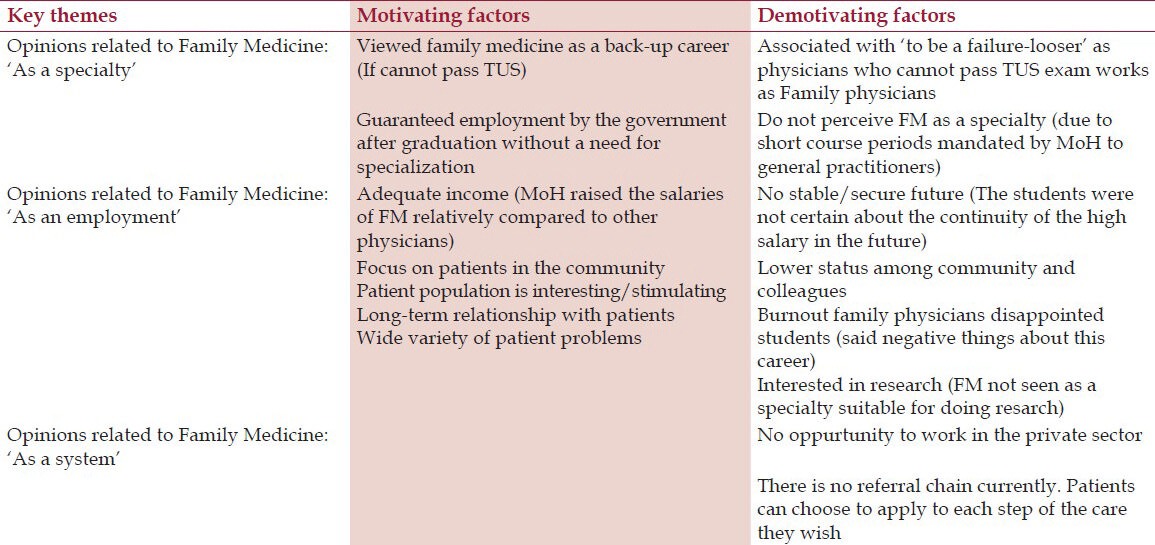

Table 1.

Key themes influencing to choose or not to choose FM as a career

Opinions related to family medicine “as a specialty”

Two apparent subdomains were mentioned within the category of opinions related to FM “as a specialty”: Influences of short duration of training for GPs to become FPs and the influences of TUS.

Influences of GP's short duration of training to become FP

Turkey has not officially set a deadline for FM to become a specialty, which mandates postgraduate specialty training. The Turkish MoH has also made some decisions in relation to the development of family health centers. Practitioners need to become an FP to work in these centers and therefore need to retrain completing a 1-week course. This was certainly not an appealing condition to medical students. The majority of the students we assessed from the state university reported that they did not perceive FM as a specialty because GPs get the title of “Family Physician” after completing a 1-week course, and therefore, there was a conceptual confusion among the students.

“A person who is taking the course (one week course) cannot be an expert… I do not understand why family medicine is treated like a field of expertise? Why would I choose it in TUS if they will give a certificate in 1-2 weeks? Why do they bother with the specialty?” (24 years, male, first focus group, state university).

“I think it is a nice branch, but you need to be an expert. It's not my preference under these circumstances. Lay people do not know that. ‘Family Physician’ is written on everyone's door. Oh, why would we choose the long way if we already have a shortcut?” (27 years, female, second focus group, state university).

Dual system

The students from the foundation university approached FM in a more positive way. However, they also emphasized the importance of regular residency training to become an FP. Furthermore, they have mentioned about the awkwardness of the dual system.

“I have really liked this branch of medicine but I have to admit that I have concerns on two things. Firstly, is that we do not know the future of family medicine in our country. Secondly, is that people get the title of family physician without having done their residency. I would prefer to do the residency first. However, after three years of residency you will have the same status as others. I will take TUS examination and if I don't succeed I may choose FM.” (24 years, female, second group, foundation university).

“The family physicians do not seem to be better than the general practitioners at the moment. This is not a pleasant thing to do your residency training and then do same job as general practitioners. There are no job descriptions to differentiate these two.” (24 years, male, first focus group, foundation university).

Influences of the TUS examination viewed FM as “a career failure”

All of the students viewed FM as a “career failure” as they stated that they may want to work as FPs if they could not succeed in TUS. Preferring FM in the TUS examination was often perceived by students as “to be a failure/looser,” as physicians who do not pass TUS, work as FPs without residency training. This is particularly true for high-achiever students who were encouraged to choose a specialty, which was “better” than FM.

“When people learn that I go to medical school they usually ask, “What do you want to be?” When I say, “To work in family medicine”, they reply with, “Do you go to medical school for nothing? You’re a good student. Do you really want that?” (24 years, male, first focus group, foundation university).

“I think people do not trust their family physicians. They say he could not pass the TUS exam therefore, he became a family physician.” (25 years, male, second focus group, state university).

Opinions related to family medicine “as an employment”

Three subdomains emerged within the category of opinions related to FM “as an employment”: The influences of adequate income, job satisfaction, and prestige.

Influences of adequate income

The participants viewed FM as a guaranteed employment by the government after graduation without a need for specialization. The MoH raised the salaries relatively for FP compared with other physicians, and therefore, adequate income was an attractive factor for the students. They thought they could work as a FP for 1 or 2 years to earn some money. However, at the same time, they stated that this increase in the salaries would not last long, and they pointed out that there was no stable/secure future.

“I might think to become a FP for a short duration of time. They earn a good salary at the moment, but we do not know if this will continue in the future. First I want to earn some money, and then go and do my residency.” (24 years, female, third focus group, state university).

Influences of job satisfaction

The data showed that the students had both positive and negative views about job satisfaction in primary care. The participants from both universities (state and foundation) were aware of the heavy workload of FPs. They have stated that dealing with wide variety of patient problems and having deeper relationship with patients would be stimulating. However, they encountered some FPs with “burnout” during their clerkships, and this disappointed them. They mentioned about the negative performance criteria, which means getting negative points if you miss to vaccinate a child or do not give prenatal care to the pregnant women in your region. Some of the students had concerns that they would have no opportunity to work in the private sector because there is no payroll for FP there. Finally, a few students pointed out that they were interested in research and thought that FM was not a suitable specialty for doing research.

“You follow the same patient for a very long time. If the patient recovers everything is fine. But, usually they have chronic problems and it is tiring for the physician. But on the other hand, you deal with a wide variety of patient problems which makes the practice dynamic.” (23 years, female, second focus group, foundation university).

Influences of prestige

The majority of the students perceived FM as having a lower status among the community and colleagues and having a decreased scientific prestige compared with other specializations.

“I know that some of my patients don't know how to read and write. But even these people may say that, “This doctor's (FP) education is not enough.” (26 years, male, first focus group, foundation university).

Opinions related to family medicine “as a system”

It would be worth to note that FPs do not have a “gate-keeper role” in Turkey. Because there is currently no referral chain, patients can choose to apply their own path of care as they wish. Some of the students stated that if there was a referral system, they might think of becoming an FP because in that way, they hold the power over patients. Another issue was that FPs were perceived as service providers that have to obey patients’ demands for prescription refills rather than allowing them to utilize their full scope of practice.

“I would think of family medicine if there was a referral system… because that way the patients would think that you are an important person and would listen to you more.”(27 years, female, second focus group, state university).

“Patients might perceive you as the person who writes the prescription refills.” (25 years, male, second focus group, state university)

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that although there is an increasing demand, FM specialty does not seem to be on the list of career options among medical students, and it is perceived as an unattractive branch of the medicine. Despite the Turkish MoH trying to give the GPs and primary care physicians more centralized roles in the significant reorganization, the medical specialists still seem to be at the core of the Turkish health-care system.[5]

Khader et al. reported from Jordan that FM was among one of the unpopular specialty preferences with medical students, which seems to be similar with the findings of other studies.[6,7,8] Identical trends were noted from Canada and the United States over the last decade, which have shown a declining interest in FM.[9,10,11]

Schafer et al. indicated that students who do not think FM in their career options were more likely to report lower prestige, lower intellectual content, and concerns about the wide content area as reasons for the rejection.[12] In different countries that have a decreased number of students in choosing FM, the primary influences have been postulated as multifactorial, complex, dynamic, and individualized. Unique features of medical school,[13,14,15,16,17,18] personal exposure,[19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] and lifestyle preferences, in addition to workplace factors, expected income, and high prestige, were the factors reported to be associated with choosing FM. Medical educators, on the other hand, have primarily emphasized the educational influences such as curriculum, primary care experiences, and faculty role models.[27] In the present study, the medical students also mentioned these factors, but the main concern of the Turkish students was the lack of postgraduate training. One striking finding of the current study was that the final-year medical students stated that they have not perceived FM as a specialty and thought that without residency training, they would not consider FM specialty among their career options. Furthermore, the dual system in Turkey, as a consequence of health reform, affected the students not to choose FM as a career choice. The possibility to get into the system without residency training has resulted in some confusion, and the students thought that they were wasting time with residency training because the difference was not perceived by lay people. Although they have underlined good salaries to be as one of the attractive points, they thought that the uncertainties in the job descriptions and the unstable or insecure professional future made them move away from FM.

Edirne et al. from Turkey have reported that physicians without any postgraduate training caused a lack of respect and trust among the majority of people in Turkey.[2] In Europe, it is not possible to work as an FP without specific training[28] (exceptions include Hungary (no longer than 5 years), Romania, Croatia, and Montenegro).

At this point, several possible solutions are needed to reassure medical students of FM specialty in the future. First, an announcement of a deadline for the official date of change might transform the perception of students about FM as a specialty. After this date, there should be only one way to enter the primary health-care system as an FM specialist. At least 3-year residency training should be mandatory. Furthermore, as Guldal et al. have stated, FM is best learned within general practice; therefore, half of the training time should be given in a primary care setting.[29] Primary care should be the learning ground for the FM specialty training; therefore, universities and primary care should work collaboratively.[30]

The qualitative methodology of our study can be viewed as both a limitation and strength of the manuscript. A limitation to our study is that the qualitative methodology used was not designed to produce generalizable results beyond the study participants, although as found here, the design provides useful insight into the Turkish medical students’ perspectives of FM as a specialty. Another is the limited coverage of the students from two universities in Istanbul. Further studies are needed to investigate the rationale for the declining student interest in FM and to recommend changes in the training programmes.

Conclusions

Currently, the Family Medicine specialty does not seem to be a forefront option when career planning by medical students. Lack of prestige and lower satisfaction levels at work, not perceiving FM as a field of expertise, and the adverse conditions at work, which may originate from duality in the system, may constrain the students from choosing it.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ersoy F, Sarp N. Restructuring the primary health care services and changing profile of family physicians in Turkey. Fam Pract. 1998;15:576–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.6.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edirne T, Bloom P, Ersoy F. Update on family medicine in Turkey. Fam Med. 2004;36:311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basak O. Part-time distance training and its place in medical education. Turk J Fam Pract. 2012;16:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kisa S, Kisa A. National health system steps in Turkey: Concerns of family physician residents in Turkey regarding the proposed national family physician system. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2006;25:254–62. doi: 10.1097/00126450-200607000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asan A. Overview of specialty training in medicine: Problems and solutions. Akademik Dizayn Dergisi. 2007;1:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khader Y, Al-Zoubi D, Amarin Z, Alkafagei A, Khasawneh M, Burgan S, et al. Factors affecting medical students in formulating their specialty preferences in Jordan. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pugno PA, McPherson DS, Schmittling GT, Kahn NB., Jr Results of the 2001 National Resident Matching Program: Family practice. Fam Med. 2001;33:594–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: A reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:502–12. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skinner BD, Newton WP. A long-term perspective on family practice residency match success: 1984-1998. Fam Med. 1999;31:559–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn NB, Jr, Schmittling GT, Graham R. Results of the 1999 National Resident Matching Program: Family practice. Fam Med. 1999;31:551–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pugno PA, McPherson DS, Schmittling GT, Kahn NB., Jr Results of the 2000 National Resident Matching Program: Family practice. Fam Med. 2000;32:543–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schafer S, Shore W, French L, Tovar J, Hughes S, Hearst N. Rejecting family practice: Why medical students switch to other specialties. Fam Med. 2000;32:320–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Watkins AJ, Bastacky S, Killian C. A systematic analysis of how medical school characteristics relate to graduates’ choices of primary care specialties. Acad Med. 1997;72:524–33. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199706000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitcomb ME, Cullen TJ, Hart LG, Lishner DM, Rosenblatt RA. Comparing the characteristics of schools that produce high percentages and low percentages of primary care physicians. Acad Med. 1992;67:587–91. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen SS, Sherman MB, Bland CJ, Fiola JA. Effect of early exposure to family medicine on students’ attitudes toward the specialty. J Med Educ. 1987;62:911–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campos-Outcalt D, Senf JH. Characteristics of medical schools related to the choice of family medicine as a specialty. Acad Med. 1989;64:610–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duerson MC, Crandall LA, Dwyer JW. Impact of a required family medicine clerkship on medical students’ attitudes about primary care. Acad Med. 1989;64:546–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meurer LN. Influence of medical school curriculum on primary care specialty choice: Analysis and synthesis of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70:388–97. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199505000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basco WT, Jr, Buchbinder SB, Duggan AK, Wilson MH. Associations between primary care-oriented practices in medical school admission and the practice intentions of matriculants. Acad Med. 1998;73:1207–10. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199811000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz LA, Sarnacki RE, Schimpfhauser F. The role of negative factors in changes in career selection by medical students. J Med Educ. 1984;59:285–90. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paiva RE, Vu NV, Verhulst SJ. The effect of clinical experiences in medical school on specialty choice decisions. J Med Educ. 1982;57:666–74. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiner E, Stoken JM. Overcoming barriers to generalism in medicine: The residents’ perspective. Acad Med. 1995;70(Suppl):94. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199501000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Connelly MT, Sullivan AM, Peters AS, Clark-Chiarelli N, Zotov N, Martin N, et al. Variation in predictors of primary care career choice by year and stage of training. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:159–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.01208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geertsma RH, Romano J. Relationship between expected indebtedness and career choice of medical students. J Med Educ. 1986;61:555–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mutha S, Takayama JI, O’Neil EH. Insights into medical students’ career choices based on third- and fourth-year students’ focus-group discussions. Acad Med. 1997;72:635–40. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199707000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tardiff K, Cella D, Seiferth C, Perry S. Selection and change of specialties by medical school graduates. J Med Educ. 1986;61:790–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198610000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saigal P, Takemura Y, Nishiue T, Fetters MD. Factors considered by medical students when formulating their specialty preferences in Japan: Findings from a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oleszczyk M, Svab I, Seifert B, Krztoń-Królewiecka A, Windak A. Family medicine in post-communist Europe needs a boost. Exploring the position of family medicine in healthcare systems of Central and Eastern Europe and Russia. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guldal D, Windac A, Maagaard R, Allen J, Kjaer NK. Educational expectations of GP trainers. A EURACT needs analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2012;18:233–7. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2012.712958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metsemakers JF. Family medicine training in Turkey: Some thoughts. Turk J Fam Med. 2012;16:23–34. [Google Scholar]