Abstract

CONTEXT:

Pancreatic necrosis is a local complication of acute pancreatitis. The development of secondary infection in pancreatic necrosis is associated with increased mortality. Pancreatic necrosectomy is the mainstay of invasive management.

AIMS:

Surgical approach has significantly changed in the last several years with the advent of enhanced imaging techniques and minimally invasive surgery. However, there have been only a few case series related to laparoscopic approach, reported in literature to date. Herein, we present our experience with laparoscopic management of pancreatic necrosis in 28 patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A retrospective study of 28 cases [20 men, 8 women] was carried out in our institution. The medical record of these patients including history, clinical examination, investigations, and operative notes were reviewed. The mean age was 47.8 years [range, 23-70 years]. Twenty-one patients were managed by transgastrocolic, four patients by transgastric, two patients by intra-cavitary, and one patient by transmesocolic approach.

RESULTS:

The mean operating time was 100.8 min [range, 60-120 min]. The duration of hospital stay after the procedure was 10-18 days. Two cases were converted to open (7.1%) because of extensive dense adhesions. Pancreatic fistula was the most common complication (n = 8; 28.6%) followed by recollection (n = 3; 10.7%) and wound infection (n = 3; 10.7%). One patient [3.6%] died in postoperative period.

CONCLUSIONS:

Laparoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy is a promising and safe approach with all the benefits of minimally invasive surgery and is found to have reduced incidence of major complications and mortality.

Keywords: Laparoscopic necrosectomy, necrotizing pancreatitis, retroperitoneal, transgastric, transluminal

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is usually a self-limiting disease and resolve without serious complications. However, 25% of patients with AP will develop a more severe form of the disease and is associated with the development of potentially life-threatening complications like necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma, the peripancreatic tissue or both.[1] According to the Revised Atlanta Classification (2012), AP can be subdivided into two types: Interstitial oedematous pancreatitis and necrotizing pancreatitis. Interstitial edematous pancreatitis usually resolves within the first week. The natural history of necrotizing pancreatitis is variable. It may remain solid or liquefy, remain sterile or become infected, persist, or disappear over time.[2]

In the Revised Atlanta Classification, clear definitions of pancreatic and peripancreatic collections are made. Acute peripancreatic fluid collection (APFC) and pancreatic pseudocyst occur in the setting of interstitial oedematous pancreatitis. APFCs do not have a well-defined wall, are homogeneous, are confined by normal fascial planes in the retroperitoneum, and may be multiple. Most acute fluid collections remain sterile and usually resolve spontaneously without intervention. Pancreatic pseudocyst presents as a delayed (usually >4 weeks) complication of interstitial oedematous pancreatitis with a well-defined wall and devoid of solid material.[2]

In necrotizing pancreatitis, necrosis may be an acute necrotic collection (ANC) without definite demarcation in the early phase or walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN), which is surrounded by a radiologically identifiable capsule. It is difficult to differentiate an APFC from an ANC in the first week. At this stage, both types of collections will appear as areas with fluid density in contrast enhanced CT abdomen (CECT). After the first week, the distinction becomes clear. A peripancreatic collection associated with pancreatic parenchymal or peripancreatic necrosis can be properly termed as ANC. MRI, transabdominal ultrasonography or endoscopic ultrasonography may be helpful to confirm the presence of solid content in the collection. WOPN is a mature, encapsulated collection of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis. This maturation usually occurs ≥4 weeks after onset of necrotizing pancreatitis.[2]

The current standard of care in treating AP has been outlined by the International Acute Pancreatitis (IAP) guidelines where debridement and drainage is advised for infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN).[3] Surgery is also advised for symptomatic organized necrosis and sterile necrosis with clinical deterioration.[1] The traditional surgical approach to pancreatic necrosis was open necrosectomy which aims at wide drainage of all infected collections and complete removal of all necrotic tissue with the placement of drains for continuous postoperative closed lavage. Frequently, repeat laparotomy was needed to ensure complete debridement.[3] But open approach was associated with substantial morbidity and rates of perioperative mortality that exceeded 50% in some reports.[4,5]

Gagner first described minimally invasive surgical treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis in 1996, including laparoscopic retrocolic, retroperitoneoscopic, and transgastric procedures.[6] It is becoming increasingly clear that an expectant "step-up" approach to debridement and drainage may be a more appropriate strategy to reduce inflammation and eliminate microbial burden.[7] We present a retrospective study of 28 such cases managed laparoscopically along with a review of the literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were collected retrospectively from our institution's medical records from 2002 to 2012. A detailed study of 28 cases of laparoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy was carried out. All the patients were referred by medical gastroenterologists, who while on treatment or follow up for AP were found to require surgical intervention for pancreatic necrosis. Apache II score of these patients ranged from 7 to 15 at the time of presentation. Seven patients had WOPN, which was detected on follow up. These patients were stable and ambulatory, but presented with recurrent abdominal pain, abdominal distension or fever and chills, after recovering from AP. Remaining 21 patients were stable, recovering patients, who were managed in intensive care unit. Ten of these patients had ultrasound guided pig tail drainage of the necrosis, following which they improved and became fit for the definitive surgery.

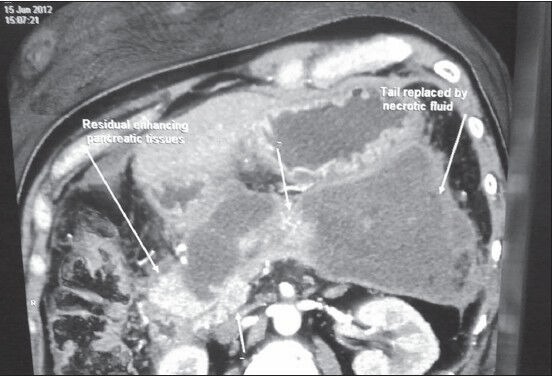

All the 28 patients had abdominal pain and distension while 22 patients had fever with chills. Sixteen patients were diagnosed to have necrosis following admission for acute severe pancreatitis in our institution, when follow up CT was done due to slow recovery or unexplained deterioration. Twelve patients were referred from elsewhere following management of acute severe pancreatitis. Eighteen patients had history of gallstone disease while twelve patients were alcoholic. The preoperative investigations included abdominal ultrasound, CECT (Figure 1) and routine blood investigations.

Figure 1.

CECT abdomen showing pancreatic necrosis

All patients were managed by laparoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy, except for two cases that required conversion to open surgery, due to extensive dense adhesions. Timing of necrosectomy was 22-35 days (average - 27.6 days) after onset of symptoms. Prophylactic antibiotic was given just after induction of general anaesthesia, if not started prior. Ryles tube was introduced in all cases and retained postoperatively.

Technique

Patient was positioned in French position. Operating surgeon stood in between the legs of the patient. Camera assistant stood on right side of the patient while first assistant and scrub nurse stood on left side. Monitor was positioned over left shoulder of the patient, closer to midline. Pneumoperitoneum was created after insertion of 12 mm optical trocar infraumbilically. Diagnostic laparoscopy was done. Two lateral pararectal trocars were inserted under vision. Peripancreatic adhesions were released by blunt dissection.

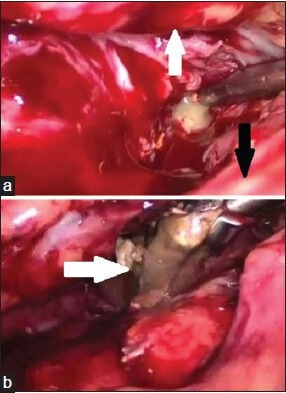

Access to the pancreatic necrotic tissue was decided based on the status and site of the necrosis, as demonstrated by preoperative CECT. Retrogastric approach was preferred in ANC. Retrogastric approach may be transgastrocolic or transmesocolic/infracolic[8] approach. In transgastrocolic approach [Figure 2a], gastrocolic ligament was opened to access the necrosed tissue. It was the preferred approach for necrosis involving head and body of pancreas and was used in 21 patients. In transmesocolic or infracolic approach, the mesocolon was opened near ligament of Treitz, between middle colic artery and left colic artery. It was the preferred approach in necrosis involving tail region of pancreas and was used in one patient. Necrotic tissue was dissected and removed [Figure 2b] using blunt dissection in an endobag. Resultant cavity was washed thoroughly with normal saline and two 30F tube drains [Figure 3] were positioned inside the cavity for post-operative lavage.

Figure 2.

Intra-operative images of (a) transgastrocolic approach to pancreatic necrotic tissue; stomach (white arrow), colon (black arrow) and (b) pancreatic necrotic tissue (white arrow) delivered out of the necrotic cavity

Figure 3.

Intra-operative image of drains (black arrows) kept into necrotic cavity

Transgastric and intracavitary approaches were preferred in patients with WOPN or predominantly liquid necrosis. If adequate gastric distension was possible, intracavitary approach was preferred and was used in one patient. Transgastric approach was used in four patients. In transgastric approach, 8-cm distal gastrotomy in the anterior wall of the stomach was created with the use of the 5-mm ultrasonic dissector. The lesser sac was entered, after confirming by aspiration, through a convenient point along the posterior gastric wall, using ultrasonic dissector. A gastrotomy, approximately 5 cm in size was created with linear stapler in the posterior gastric wall. Pus was aspirated and the cavity was thoroughly irrigated and lavaged with warm normal saline. Pancreatic necrosectomy was performed using a suction device and non-traumatic grasping forceps. The debrided tissue was removed in an endobag. The lesser sac was copiously irrigated again with warm normal saline. The anterior gastrotomy was closed and the peritoneal cavity was lavaged. A 16-Fr suction drain was placed in the left subphrenic space to drain the residual lavage fluid. In intracavitary approach, after insertion of the trocars, anterior stomach wall is pulled anteriorly and fixed to anterior abdominal wall with two transfascial sutures. Then two 5 mm trocars were inserted into stomach through 2 mm gastrotomies, one proximally on left side and next distally on right side of the patient. Stomach was insufflated with CO2 through right trocar. A 5 mm telescope was introduced through right trocar and the posterior cystogastrostomy completed using ultrasonic dissector, after confirming by aspiration. Necrotic tissue was emptied into stomach and thorough wash with warm normal saline was given.

Postoperatively, the patients were managed in the intensive care unit initially and then shifted out to ward when they were stable. In patients managed with transgastrocolic and transmesocolic approaches, drain lavage with normal saline was started from the fourth day and was continued till the drain output was clear. In the initial week, lavage was given at the rate of 100 ml/hour continuously though one drain tube and drained out through the other tube. The lavage frequency was reduced to 500 ml twice a day after 1 week. Patients were send home with the drain tubes with the advice to continue lavage at home. For 3 weeks or till the drain fluid was clear, lavage was continued. Drain tube was retained for two more weeks after cessation of lavage and removed after doing an ultrasound of the abdomen to rule out residual abscess. Eight patients developed pancreatic fistula, which was managed conservatively. Drain was retained in them till the output ceased.

Patients were followed up with ultrasound scan of abdomen after 3 months. Residual collection was found in three patients, which was drained by pigtail catheter under radiological guidance. All other patients were followed up every 6 months with ultrasound scan of abdomen for 2 years. If these patients are asymptomatic even after 2 years, annual follow up was advised.

RESULTS

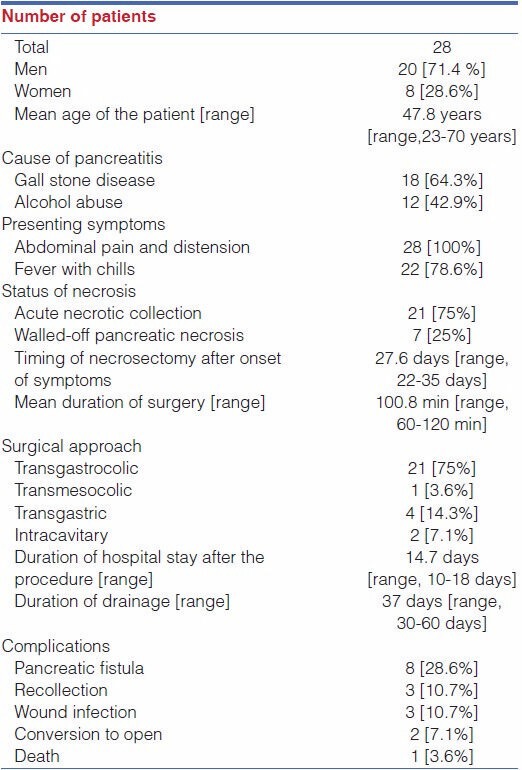

Out of 28 cases, 20 were men and 8 were women [Table 1]. Patients' age ranged from 23 to 70 years [mean age - 47.8 years]. The mean operating time was 100.8 min [range, 60-120 min]. None of the patients needed intra-operative blood transfusion. Two cases were converted to open procedure [7.1%] because of severe dense adhesions. The average duration of hospital stay after the procedure was 14.7 days [range, 10-18 days].

Table 1.

Clinical and outcome variables of patients

One patient [3.6%] died in post-operative period due to severe sepsis. Eight patients [28.6%] developed pancreatic fistula which was managed conservatively. Three patients [10.7%] had port-site infection that was managed with oral antibiotics and local wound care. Follow up ultrasound of abdomen was done in all patients after 3 months, which revealed recollection in three patients [10.7%] which was drained with pigtail catheter inserted under radiological guidance. All other patients were asymptomatic on follow-up. None of the patients developed newly detected Diabetes Mellitus or exocrine deficiency, on follow up.

DISCUSSION

AP mostly occur secondary to gallstones or excess alcohol consumption. It is usually self-limiting and localized. A proportion of these patients can develop systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).[9] Approximately, half of the deaths from AP occur within first 14 days and most of them are due to multiple organ failure. In patients who survive the initial attack, about 25% patients develop areas of pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis. Secondary infection in necrotic tissue then leads to persisting sepsis, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and accounts for the majority of the remaining late deaths.[10] Infection of pancreatic necrotic tissue significantly increases mortality [infected necrosis/sterile necrosis, 30 vs. 12 %, respectively].[3]

The diagnosis of IPN is made based on a combination of clinical manifestations, results of laboratory investigation [mainly increased levels of CRP and procalcitonin], and can be confirmed by image-guided fine-needle aspiration and culture of aspirates.[11] Plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) levels >150 mg/L suggest PN, but CRP levels seem to be equivalent in patients who do or do not have IPN.[12] Serum procalcitonin is a valuable tool in predicting the severity of AP and is used as a marker of IPN.[13] CT scan with contrast of abdomen is helpful in determining the extent of necrosis and serially monitoring the progress.[14]

A randomized trial comparing early with late necrosectomy showed better outcomes after delayed intervention [after 21 days]. During early intervention it was found that there is no demarcation of necrotic tissue, as this process takes 2-3 weeks to occur. So, it is advisable to delay intervention beyond the third week.[15]

Traditionally, surgery includes open surgical necrosectomy and extensive drainage of peripancreatic collection. During laparotomy, all the necrotic areas are debrided by finger dissection of pockets of semisolid pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis, and multiple drains are inserted. Extensive lavage and drainage are required to manage leakage of pancreatic tissue and to allow the continued flow of infected and necrotic material.[16]

Initially, it was thought that, minimally invasive procedures, including percutaneous drainage, endoscopic drainage, or minimally invasive surgery for IPN, serves as a temporary measure to bridge the critical early time after onset of acute pancreatitis to a later optimal time point for open necrosectomy.[17] But, it was disproved later by several case series.

In 2010, PANTER trial by Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group concluded that minimally invasive step-up approach, as compared with open necrosectomy, reduced the rate of the major complications or death among patients with PN and IPN.[18] With the step-up approach, more than one-third of patients were successfully treated with percutaneous drainage and did not require major abdominal surgery. After the infected fluid is drained by percutaneous drainage, the pancreatic necrosis can be left in situ, an approach that is similar to the treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis without infection. In the study, 35% of patients with IPN, who were treated with the step-up approach did not require necrosectomy. Minimally invasive surgery was indicated in patients who had ongoing sepsis even after percutaneous drainage of the infected fluid. Minimally invasive necrosectomy provoke less surgical trauma in patients who are already severely ill. This hypothesis is supported by the substantial reduction in the incidence of new-onset multiple organ failure in the step-up approach group.[18]

The laparoscopic approach has been demonstrated to be safe in several small case series. Cuschieri, in 2002, described for the first time the technique of laparoscopic infracolic necrosectomy with irrigation of the lesser sac as a valid alternative to open necrosectomy.[19] Ammori, in 2002, reported a case of IPN managed by laparoscopic transgastric approach. Operative time was 270 min. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was asymptomatic on 2 months of follow-up.[20]

Parehk, in 2006, reported a retrospective study on hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery for pancreatic necrosectomy.[21] This study described 18 patients with PN who underwent laparoscopic necrosectomy using an infracolic approach to access the lesser sac with a hand access port in order to enlarge the window in the transverse mesocolon and to bluntly remove the necrotic tissue. The outcomes were encouraging with mean length of stay of 16.3 days after the procedure and a reduction in the incidence of major wound complications.

Wani et al., in 2011, had reported minimally invasive pancreatic necrosectomy in 15 patients. Pancreatic necrosectomy was performed by laparoscopic transperitoneal approach in 12 patients [transmesocolic in 4 patients; transgastrocolic in 6 patients; and via gastrohepatic omentum in 2 patients], by retroperitoneal approach in 2 patients, and by a combination of methods in 1 patient [endoscopic transgastric drainage followed by laparoscopic intracavity necrosectomy]. There were no postoperative complications related to the procedure itself, such as major wound infections, intestinal fistulae, or postoperative hemorrhage. The average length of hospital stay after surgery was 14 days.[22]

Despite the use of less invasive techniques, complications do occur after pancreatic necrosectomy. Pancreatic and enterocutaneous fistulae occur in 30% of patients and it seems related to the severity and extent of the underlying necrosis. Fistulae should be managed conservatively initially. Surgical treatment should be delayed until pancreatitis is completely resolved. Other complications include wound infection and wound dehiscence which is less common with the laparoscopic approach. Postoperative bleeding is usually managed with endovascular techniques.[23]

Laparoscopic necrosectomy gives a better exposure of the lesser sac, left paracolic gutter and head of the pancreas, apparently overcoming the main limitation of the retroperitoneal approach in not debriding the necrotic tissue completely, with better identification of the anatomy.[23] It may also provide better access to fluid collections not amenable to endoscopic approach. These may facilitate a more thorough debridement of the necrotic cavity.[24] Endoscopic approach is technically not feasible if there is minimal liquefaction of the pancreatic necrosis, with predominant solid debris, where laparoscopic necrosectomy is preferred.[25] But the transperitoneal approach carries the risk of peritoneal contamination with infected necrosis.[23] To conclude, laparoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy is a safe approach in patients with PN and IPN. It is found to be associated with reduced incidence of major complications and mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank Prof. PK Reddy for his advice and inspiration, without which this article would not be possible. We also owe our thanks to Dr Pratap C Reddy for his kind academic support. Finally, we would like to thank our institution, Apollo Hospital (Chennai, India). We have no conflicts of interest and received no financial support for this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Doctor N, Agarwal P, Gandhi V. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. Indian J Surg. 2012;74:40–6. doi: 10.1007/s12262-011-0384-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, et al. (2013) Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–11. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhl W, Warshaw A, Imrie C, Bassi C, McKay CJ, Lankisch PG, et al. IAP Guidelines for the Surgical Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2:565–73. doi: 10.1159/000071269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mier J, León EL, Castillo A, Robledo F, Blanco R. Early versus late necrosectomy in severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:71–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besselink MG, de Bruijn MT, Rutten JP, Boermeester MA, Hofker HS, Gooszen HG. Surgical intervention in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2006;93:593–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagner M. Laparoscopic Treatment of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Semin Laparosc Surg. 1996;3:21–8. doi: 10.1053/SLAS00300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fink D, Soares R, Matthews JB, Alverdy JC. History, goals, and technique of laparoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1092–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1506-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamson GD, Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic infracolic necrosectomy for infected pancreatic necrosis. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1675. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson PG, Manji M, Neoptolemos JP. Acute pancreatitis as a model of sepsis. J Antimicrobial Chem. 1998;41:51–63. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu CY, Yeh CN, Hsu JT, Jan YY, Hwang TL. Timing of mortality in severe acute pancreatitis: Experience from 643 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1966–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i13.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakorafas GH, Lappas C, Mastoraki A, Delis SG, Safioleas M. Current trends in the management of infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2010;10:9–14. doi: 10.2174/187152610790410936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riche FC, Cholley BP, Laisne MJ, Vicaut E, Panis YH, Lajeunie EJ, et al. Inflammatory cytokines, C reactive protein, and procalcitonin as early predictors of necrosis infection in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgery. 2003;133:257–62. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mofidi R, Suttie SA, Patil PV, Ogston S, Parks RW. The value of procalcitonin at predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis and development of infected pancreatic necrosis: Systematic review. Surgery. 2009;146:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shelat VG, Diddapur RK. Minimally invasive retroperitoneal pancreatic necrosectomy in necrotising pancreatitis. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:220–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mier J, León EL, Castillo A, Robledo F, Blanco R. Early versus late necrosectomy in severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:71–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsiotos GG, Luque-de Leon E, Soreide JA, Bannon MP, Zietlow SP, Baerga-Varela Y, et al. Management of necrotizing pancreatitis by repeated operative necrosectomy using a zipper technique. Am J Surg. 1998;175:91–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner J, Feuerbach S, Uhl W, Büchler MW. Management of acute pancreatitis: From surgery to interventional intensive care. Gut. 2005;54:426–36. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuschieri A. Pancreatic necrosis: Pathogenesis and endoscopic management. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2002;9:54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic transgastric pancreatic necrosectomy for infected pancreatic necrosis. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1362. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-4202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parekh D. Laparoscopic-assisted pancreatic necrosectomy: A new surgical option for treatment of severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 2006;141:895–903. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.9.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wani SV, Patankar RV, Mathur SK. Minimally invasive approach to pancreatic necrosectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:131–6. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonsi AF, Bacchion M, Crippa S, Malleo G, Bassi C. Acute pancreatitis at the beginning of the 21st century: The state of the art. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2945–59. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bello B, Matthews JB. Minimally invasive treatment of pancreatic necrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6829–35. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ang TL. Current Status of Direct Endoscopic Necrosectomy. Proc Singapore Healthcare. 2012;21:179–86. [Google Scholar]