Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of early rehabilitation after surgery program (ERAS) in patients undergoing laparoscopic assisted total gastrectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This is a study where 47 patients who are undergoing lap assisted total gastrectomy are selected. Twenty-two (n = 22) patients received enhanced recovery programme (ERAS) management and rest twenty-five (n = 25) conventional management during the perioperative period. The length of postoperative hospital stay, time to passage of first flatus, intraoperative and postoperative complications, readmission rate and 30 day mortality is compared. Serum levels of C-reactive protein pre-operatively and also on post-op day 1 and 3 are compared.

RESULTS:

Postoperative hospital stay is shorter in ERAS group (78 ± 26 h) when compared to conventional group (140 ± 28 h). ERAS group passed flatus earlier than conventional group (37 ± 9 h vs. 74 ± 16 h). There is no significant difference in complications between the two groups. Serum levels of CRP are significantly low in ERAS group in comparison to conventional group. [d1 (52.40 ± 10.43) g/L vs. (73.07 ± 19.32) g/L, d3 (126.10 ± 18.62) g/L vs. (160.72 ± 26.18) g/L)].

CONCLUSION:

ERAS in lap-assisted total gastrectomy is safe, feasible and efficient and it can ameliorate post-operative stress and accelerate postoperative rehabilitation in patients with gastric cancer. Short term follow up results are encouraging but we need long term studies to know its long term benefits.

Keywords: Early rehabilitation after surgery (ERAS), fast track surgery, gastric cancer, perioperative period, total gastrectomy

INTRODUCTION

The continuously growing pressure upon medical systems as a result of the increasing number of patients who need a surgical procedure and as a result of the economical restrains lead to the development of a new concept: fast-track surgery (FTS).[1] This concept of fast track surgery (FTS) better called early rehabilitation after surgery program (ERAS) brings together different perioperative strategies which according to evidence-based medicine are useful strategies. The goal of the concept is to optimize the perioperative management of the patient in order to reduce morbidity, to enhance recovery of the patient after a surgical procedure, to reduce hospital stay, and to reduce costs.[1]

After major gastric surgeries a stay of 1 week is the minimum that can be expected. This prolonged post-operative stay is not only due to the morbidity associated with the disease and the operative procedure but also due to the conventional perioperative care. Inadequate pain management, intestinal dysfunction, and immobilisation have been recognized since at least 1997 as among the main factors delaying post-operative recovery in patients subjected to major surgery.[2] So this ERAS is advanced perioperative care for better outcome of the patient.

The implementation of this concept relies upon hospital policies developed and applied in all departments and services involved in the management of the surgical patients. The team approach includes a lot of medical personnel, but the main actors are the surgeon and the anesthetist, who have the most constant and direct contact with the patient.[1] The ERAS refers to all phases of perioperative care: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative strategies. The results that can be achieved with ERAS(FTS)-reductions in postoperative morbity, average length of hospital stay and the consumption of resources-are, however, significant.[3,4,5,6]

The concept of ERAS (FTS) allowing accelerated post-operative recovery is accepted in colorectal surgery, but efficacy data are only preliminary for patients undergoing total gastrectomy for carcinoma stomach. The present work compares the short and medium term results returned by ERAS (FTS) when combined with lap-assisted total gastrectomy with lap total gastrectomy alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is the comparative study, which involved 47 patients, who underwent lap-assisted total gastrectomy for carcinoma stomach between Nov 2009 to Jan 2012 with a follow up for 3 months in SCB Medical college and Hospital, Cuttack, Odisha, India. ERAS protocol for laparoscopic gastrectomy was introduced in this hospital in November 2010. Therefore, twenty-two (n = 22) patients operated between November 2010 to January 2012 formed the ERAS group. Twenty-five (n = 25) patients who underwent total gastrectomy between November 2009 to October 2010 received conventional perioperative care was assigned as a control group (n = 25). All data were retrospectively collected from patient case charts. The FTS protocol was developed by us which can fit to our setup by bringing few modifications to the published protocols.[1,3,7,8,9,10,11,12]

Inclusion Criteria

All patients had to be more than 18 years of age and,

Those suffering from carcinoma stomach in cardiac region, fundus or body of stomach requiring total gastrectomy.

Who underwent laparoscopic assisted total gastrectomy.

Exclusion Criteria

The need for emergency surgery,

An American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) class of IV,

Inability to give informed consent,

Conversion to open procedure.

Conventional Care

In conventional care group patient is kept nil per oral from the day prior to surgery, nasogastric tube is given, and stomach wash started. Patients were admitted the day before their operation. In the operating room all patients received a urinary catheter. Thirty minutes before the first incision, cefoperazone (1000 mg) and metronidazole (500 mg) were given intravenously. Patients were operated under general anesthesia. Nasogastric tubes were routinely used. In general, one drain was placed in the oesophagojejunostomy site. Postoperatively, oral intake was prohibited, and standard intravenous fluid was set at 2-2.5 L/24 h. Patients received 4000 mg of paracetamol (in four separate doses of 1000 mg). If necessary, diclofenac 150 mg in three doses of 50 mg and morphine substitutes were also given. Nasogastric tubes, drains, and catheters were removed at the surgeon's decision. After removal of the nasogastric tube, patients were allowed clear fluids. Discharge was arranged when the following criteria were met: There are no remaining lines or catheters, solid food is tolerated, there has been passage of stool, pain is controlled using oral analgesics only and the patient is able to restart basic daily activities and self-care, or function at the preoperative level.

Early Rehabilitation After Surgery Protocol

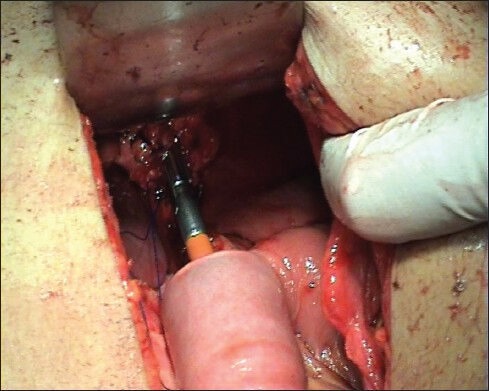

Table 1 summarizes the ERAS protocol followed for total gastrectomy during our study:

Table 1.

ERAS protocol followed during the study

Surgical technique

Is same for both conventional care group and ERAS group.

Laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy with D2 dissection

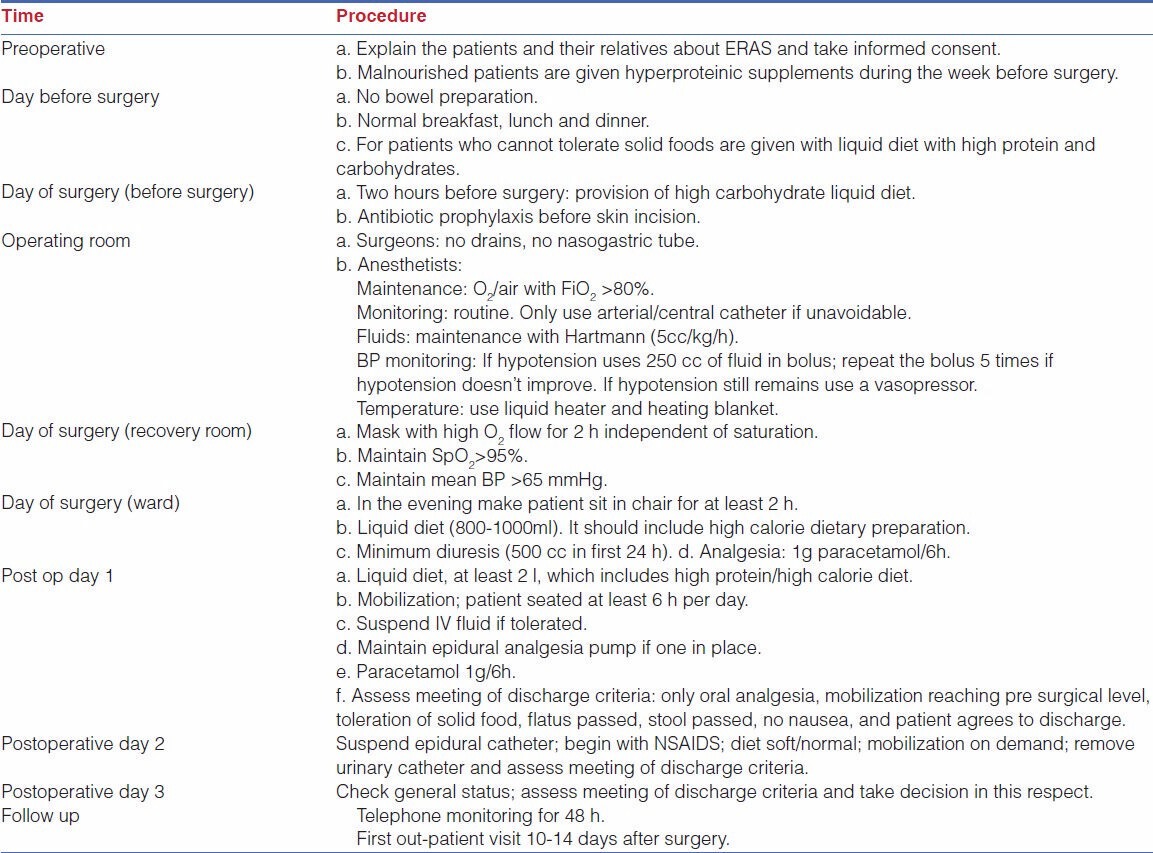

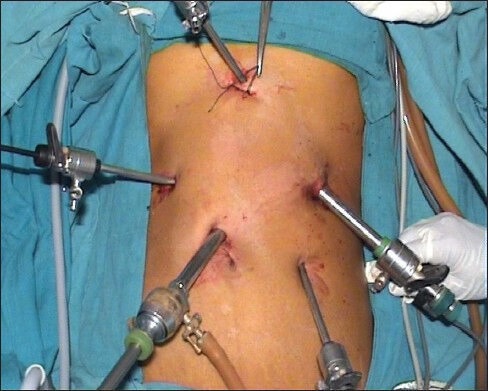

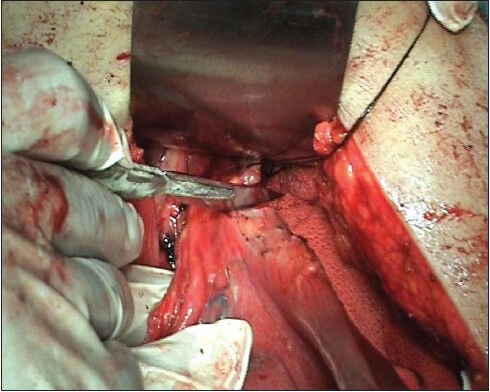

This procedure was performed for gastric cancer involving more than 2/3 of the stomach. Port position as shown in Figure 1 includes optic port near umbilicus, subxiphoid liver elevating port, right and left mid clavicular subcostal working port and left iliac fossa port for gastric retraction. The greater omentum was first dissected, using the harmonic scalpel along the border of the transverse colon. The right gastroepiploic vessel was clipped and cut at its origin with the harmonic; lymph nodes alongside of it were removed. The duodenal tunnel was made and duodenum was divided 2 cm distal to prepyloric vein. Then the left gas-troepiploic vessel was cut, allowing lymph nodes alongside it to be removed. Then the gastropan-creatic fold was exposed. Along with the gastroduodenal artery, the common hepatic artery could be skeletonized easily. The right gas-tric artery was divided and cut at its origin, from the proper hepatic artery to complete dissection of lymph nodes alongside of it. Then the lymph nodes located along the celiac trunk and the left gastric artery was removed. The left gastric artery was cut from the celiac trunk using clips. Then the splenic artery was skeletonized from its origin to the end in order to remove lymph nodes. After returning the stomach and the greater omentum to normal posi-tion, the lesser omentum could be resected close to the liver edge to the esophagogastric junction, with dissec-tion of lymph nodes. Lastly lymph nodes along the hepatic artery were dissected. After standard D2 dissection was completed, an upper midline incision (about 10 cm) was made. The gastrectomy was performed using knife at the oesophago-gastric junction [Figure 2] and oesophagojejunostomy was done using circular stapler (Ethicon make) [Figure 3] and jejunojejunostomy was done to complete Roux-en-y anastomosis.

Figure 1.

Port position

Figure 2.

Dividing gastro esophageal junction using knife

Figure 3.

Esophago-jejunostomy using circular stapler

Stastical Analysis

All collected data were entered in a database and analyzed using SPSS Statistics 17.0 for Windows. To determine significant differences between the ERAS and control groups, statistical analysis was performed using a χ2 test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous data are expressed as median (range) or as mean (±SD) and were analyzed using Mann–Whitney U test. BMI was converted to a categorical variable, representing certain risk groups. All categorical and dichotomous variables were analyzed using χ2 test.

RESULTS

Seventy-eight patients with the diagnosis of gastric cancer were referred to our hospital from November 2009 to January 2012. Of these patients, 52 were eligible to enter the study. Five patients were excluded thereafter because of distant nodal involvement, liver metastases or peritoneal carcinosis found intraoperatively or conversion to open surgery.

Among the 47 patients left for study who underwent lap assisted total gastrectomy (26 males and 21 females; median age 68, range 38-75), 22 received ERAS protocol (46.8%) and rest 25 conventional care during perioperative period (53.2%). The patients were followed up for 3 months.

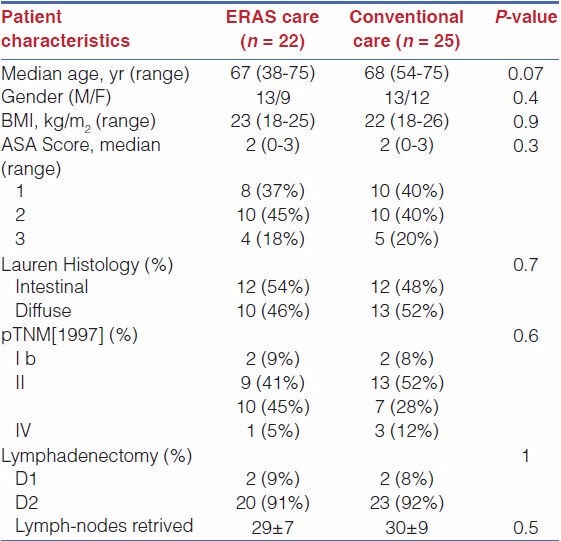

There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to demographics and preoperative data considered, type of resection, type of lymphadenectomy, and number of harvested lymph nodes. The mean preoperative hospital stay was 0.82 days (SD: 1.93). The mean duration of surgery was 184.4 min. The median length of time spent in the recovery room was 90 min (60-240 min).

The characteristics of the study population and the surgical procedure details are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical and pathologic details

Clinical Outcome

The intestinal function was defined as passage of flatus, morbidity requiring treatment during the first 30 postoperative days, postoperative hospital stay time, and readmission rate. No patient was lost during the follow-up. General complications were defined as those occurred in the cardiovascular, pulmonary, thromboembolic, urinary systems, while surgical complications were defined as wound complication, anastomotic leak, and bowel obstruction requiring reoperation.[13]

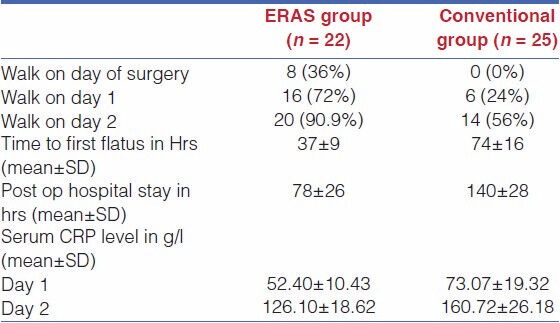

The intestinal function of patients in the fast track rehabilitation program group and conventional care group became normal 37 ± 9 h (mean ± SD) and 74± 16 h (mean ± SD), respectively, after lap assisted total gastrectomy. The median postoperative hospital stay time was 78 ± 26 h and140 ± 28 h, respectively, for the patients in the fast track rehabilitation program group and conventional care group. The postoperative rehabilitation was also faster in patients of the fast track rehabilitation program group than in those of conventional care group. On the day of surgery, eight patients (36%) in the fast track rehabilitation program group and no patient in the conventional care group were able to walk. On postoperative day 1, 16 patients (72%) in the fast track rehabilitation program group and 6 patients (24%) in the conventional care program group were able to walk. On postoperative day 2, 20 patients (90.9%) in the fast track rehabilitation program group and 14 patients (56%) in the conventional care group were able to walk [Table 3].

Table 3.

Outcome of the study

The urethral catheter in 18 patients (81%) of the fast track rehabilitation program group and in 5 patients (20%) of the conventional care group was removed on day 1 after surgery (P < 0.05), and in 20 patients (92%) of the fast track rehabilitation program group and in 11 patients (45%) of the conventional care group on day 2 after surgery (P < 0.05). Urinary retention occurred in one patient (5%) of the fast track rehabilitation program group and in four patients (16%) of the conventional care group. Urethral catheter was inserted again in one patients of the fast track rehabilitation program group and in four patients of the conventional care group.

No significant difference was observed in re-admission rate between the two groups within 30 d after resection of gastric cancer. One patient (4%) in the fast track rehabilitation program group was readmitted due to wound infection, and no readmission in the conventional care group.

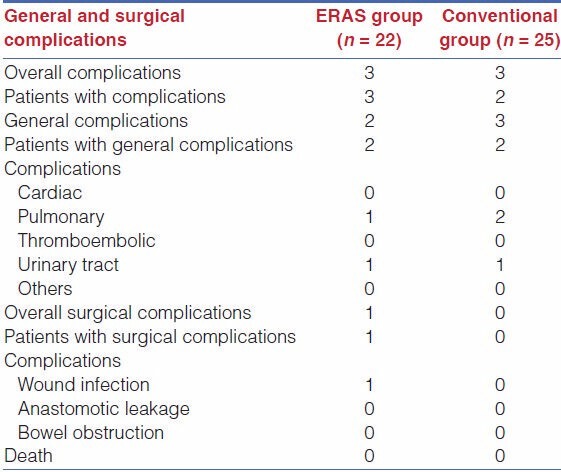

There was no difference with relation to complications between the two groups.

The types of complications are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

General and surgical complications

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study indicate that fast-track rehabilitation program can significantly accelerate the restoration of gastrointestinal function and reduce the hospital stay time of patients after total gastrectomy. The results of this study show that preoperative education of patients, epidural anesthesia or regional anesthesia, early ambulation and early postoperative oral nutrition are the important predictors for the rehabilitation of patients after total gastrectomy.

Preoperative education of patients is regarded as one of the crucial factors for fast-track rehabilitation. It is necessary to explain the detailed treatment plan, different stages of fast-track rehabilitation program and relevant measures for recovery for the patients in order to make them better understand the importance of fast-track rehabilitation program. Generally, since the gastric emptying time of solid meal and fluid is 6 and 2 h, respectively,[14] the patients should be encouraged to have liquid meal 2 h before operation instead of fasting. It has been shown that preoperative oral carbohydrate is safe and can efficiently reduce complications.[15]

Nasogastric tube: The rationale for using prophylactic nasogastric decompression tubes has been a reduction of postoperative nausea and vomiting, a decrease of abdominal distension, less chance of pulmonary aspiration, reduced risk of wound separation and infection, earlier return of bowel function and shorter duration of hospital stay.[16] A more recent systematic review of 28 randomized controlled trials (RCT) by Nelson et al., in 2005 showed that patients without or selective nasogastric tubes experienced earlier bowel movements, a decrease in pulmonary complications and a marginal increase in wound infection and ventral hernia formation.[16] They conclude that nasogastric decompression does not achieve the intended goals and should therefore be abandoned as a routine technique and only applied in selected cases.

The role of epidural anesthesia or regional anesthesia in fast-track rehabilitation program should be stressed. Postoperative epidural analgesia can avoid stress-induced neurological, endocrinological and homeostatic changes or the blocking of sympathetic nerve-related surgical stress response, reduce complications such nausea, vomiting and enteroparalysis after operation, early ambulation, improve the intestinal function and shorten the hospital stay time of patients after resection of gastric cancer.[17,18,19,20,21,22,23]

Mechanical bowel preparation prior to abdominal surgery is aimed at cleaning the large bowel of feces and thereby reducing the probability of abdominal infections and postoperative complications. For decades the practice of bowel preparation has been considered as an essential part in the prevention of postoperative complications induced by bacterial contamination. Although the use of mechanical bowel preparation has been generally accepted, a mandatory correlation between prepared bowels and a reduction of postoperative morbidity was not clearly shown. On the contrary, studies evaluating the outcome of patients with filled bowels undergoing emergency surgery found no increase in anastomotic complications as might have been expected.[10] These data suggest that the use of bowel cleansing may be unnecessary. Additionally, mechanical bowel preparation causes significant discomfort due to nausea, abdominal bloating, and diarrhea in almost all patients.[12] Physiological changes include electrolyte imbalance and dehydration. In view of the possible disadvantages and the evidence of several randomized studies, mechanical bowel preparation in the classic way should be abandoned. A preoperative enema appears to be sufficient to remove solid parts of feces.

Early postoperative oral nutrition also plays an essential part in fast-track rehabilitation program. Food intake can stimulate gastrointestinal peristalsis, and early feeding during the first 24 h after surgery promotes the recovery of ileus. It has been illustrated that early postoperative oral nutrition attenuates catabolism and potentially decreases infectious complications.[24,25] Animal trials have shown that starvation reduces collagen content in anastomotic scar tissues and impairs the healing process while feeding increases collagen deposition and strength.[26,27] Regarding these findings, several trials on humans undergoing gastrointestinal surgery were performed to evaluate differences between both concepts. A meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials by Lewis et al., showed that early enteral feeding may be beneficial for patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery.[28] Enforced postoperative mobilization of patients can reduce protein loss due to long-term bedridden, pulmonary infection and venous thrombosis. In this study, complete analgesia, control of nausea and vomiting, early postoperative oral nutrition and early ambulation efficiently reduced the postoperative complication of ileus and improved the recovery of intestinal function.

In this study, the early removal of gastric tube and urethral catheter decreased not only the infectious complications in cardiopulmonary and urinary systems but also the symptoms of patients. The shortened fasting time, preoperative carbohydrate load, and intraoperative fluid restriction effectively protected against homeostasis in patients after total gastrectomy. The outcome of fast-track rehabilitation program was better than that of conventional care.

Recently, laparoscopic surgery, applied in treatment of colorectal and early gastric cancer, can significantly reduce trauma and speed up the rehabilitation of patients after surgery. It was reported that the hospital stay time is shorter and the morbidity and readmission rate are lower after laparoscopic surgery.[29,30] However, these studies only compared open surgery with laparoscopic surgery rather than laparoscopic surgery with fast-track rehabilitation program.[29,30] Therefore, we in this study have focused on the potential influence of laparoscopy assisted surgery with or without fast-track rehabilitation program on the recovery of patients after total gastrectomy. Laparoscopic surgery and fast-track rehabilitation program can effectively promote the recovery of patients after resection of gastric cancer.

We believe that laparoscopic surgery in combination with ERAS program is significantly advantageous over other procedures for patients after resection of gastric cancer.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, ERAS program plays an important role in the recovery of patients after lap-assisted total gastrectomy, which can accelerate the restoration of their gastrointestinal function, decrease their postoperative complications, and shorten their hospital stay time.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grigoras J. Fast track surgery- A new concept- The perioperative anesthetic management. Jurnalul de Chirurgie, Iasi. 2007;3:Nr.2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:606–17. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson AD, McNaught CE, MacFie J, Tring I, Barker P, Mitchell CJ. Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization and standard perioperative surgical care. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1497–504. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Senagore AJ, Robinson B, Halverson AL, Remzi FH. ‘Fast Track’ postoperative management protocol for patients with high co-morbidity undergoing complex abdominal and pelvic colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1533–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kehlet H, Mogensen T. Hospital stay of 2 days after open sigmoidectomy with a multimodal rehabilitation programme. Br J Surg. 1999;86:227–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephen AE, Berger DL. Shortened length of stay and hospital cost reduction with implementation of an accelerated clinical care pathway after elective colon resection. Surgery. 2003;133:277–82. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183:630–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delaney CP, Zutshi M, Senagore AJ, Remzi FH, Hammel J, Fazio VW. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial between a pathway of controlled rehabilitation with early ambulation and diet and traditional prospective care after laparotomy and intestinal resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:851–9. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gatt M, Anderson AD, Reddy BS, Hayward-Sampson P, Tring IC, MacFie J. Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization of surgical care in patients undergoing major colonic resection. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1354–62. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoo CK, Vickery CJ, Forsyth N, Vinall NS, Eyre-Brook IA. A prospective randomized controlled trial of multimodal perioperative management protocol in patients undergoing elective colorectal resection for cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;245:867–72. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000259219.08209.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maessen J, Dejong CH, Hausel J, Nygren J, Lassen K, Andersen J, et al. A protocol is not enough to implement an enhanced recovery programme for colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2007;94:224–31. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez JM, Blasco JA, Roig JV, Maeso-Martínez S, Casal JE, Esteban F, et al. Enhanced recovery in colorectal surgery: A multicentre study. BMC Surg. 2011;11:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ljungqvist O, Søreide E. Preoperative fasting. Br J Surg. 2003;90:400–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis SJ, Egger M, Sylvester PA, Thomas S. Early enteral feeding versus “nil by mouth” after gastrointestinal surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. BMJ. 2001;323:773–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson R, Tse B, Edwards S. Systematic review of prophylactic nasogastric decompression after abdominal operations. Br J Surg. 2005;92:673–80. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CL, Cohen SR, Richman JM, Rowlingson AJ, Courpas GE, Cheung K, et al. Efficacy of postoperative patient-controlled and continuous infusion epidural analgesia versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with opioids: A meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1079. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200511000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carli F, Mayo N, Klubien K, Schricker T, Trudel J, Belliveau P. Epidural analgesia enhances functional exercise capacity and health-related quality of life after colonic surgery: Results of a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:540–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clemente A, Carli F. The physiological effects of thoracic epidural anesthesia and analgesia on the cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal systems. Minerva Anestesiol. 2008;74:549–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberg RB, Liu SS, Wu CL, Mackey DC, Grass JA, Ahlén K, et al. Comparison of ropivacaine-fentanyl patient controlled epidural analgesia with morphine intravenous patient-controlled analgesia for perioperative analgesia and recovery after open colon surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2002;14:571–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(02)00451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taqi A, Hong X, Mistraletti G, Stein B, Charlebois P, Carli F. Thoracic epidural analgesia facilitates the restoration of bowel function and dietary intake in patients undergoing laparoscopic colon resection using a traditional, nonaccelerated, perioperative care program. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:247–52. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marret E, Remy C, Bonnet F. Meta-analysis of epidural analgesia versus parenteral opioid analgesia after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2007;94:665–73. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Augestad KM, Delaney CP. Postoperative ileus: Impact of pharmacological treatment, laparoscopic surgery and enhanced recovery pathways. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2067–74. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i17.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen HK, Lewis SJ, Thomas S. Early enteral nutrition within 24h of colorectal surgery versus later commencement of feeding for postoperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD004080. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004080.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gatt M, MacFie J. Randomized clinical trial of the impact of early enteral feeding on postoperative ileus and recovery (Br J Surg 2007; 94: 555-561) Br J Surg. 2007;94:1044–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward MW, Danzi M, Lewin MR, Rennie MJ, Clark CG. The effects of subclinical malnutrition and refeeding on the healing of experimental colonic anastomoses. Br J Surg. 1982;69:308–10. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800690604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenstein A, Rogers P, Moss G. Doubled fourth-day colorectal anastomotic strength with complete retention of intestinal mature wound collagen and accelerated deposition following immediate full enteral nutrition. Surg Forum. 1978;29:78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis SJ, Egger M, Sylvester PA, Thomas S. Early enteral feeding versus “nil by mouth” after gastrointestinal surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. BMJ. 2001;323:773–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Lee IK, Lee YS, Kang WK, Park JK, Oh ST, et al. A comparative study on the short-term clinicopathologic outcomes of laparoscopic surgery versus conventional open surgery for transverse colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1812–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0348-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steele SR, Brown TA, Rush RM, Martin MJ. Laparoscopic vs open colectomy for colon cancer: Results from a large nationwide population-based analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:583–91. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]