Abstract

Identifying predictors of evidence-based practice (EBP) use, such as supervision processes and therapist characteristics, may support dissemination. Therapists (N = 57) received training and supervision in EBPs to treat community-based youth (N = 136). Supervision involving modeling and role-play predicted higher overall practice use than supervision involving discussion, and modeling predicted practice use in the next therapy session. No therapist characteristics predicted practice use, but therapist sex and age moderated the supervision and practice use relation. Supervision involving discussion predicted practice use for male therapists only, and modeling and role-play in supervision predicted practice use for older, not younger, therapists.

Keywords: clinical supervision, therapist characteristics, treatment adherence, evidence based practices

Establishing effective, evidence-based care in community practice contexts for youth has emerged as one of the dominant challenges of the past decade in mental health services research and implementation. By community practice, we are referring to community-based agencies that provide mental health services to youth, both children and adolescents. Despite the wealth of treatments that have demonstrated efficacy in university-based randomized clinical trials (Chorpita et al., 2011; Weisz, 2004), the degree to which the findings from research trials retain their effectiveness when implemented in practice settings is a matter of some concern (Weisz, Jensen-Doss, & Hawley, 2006). Practices tested and found to be effective in randomized clinical trials—hereafter referred to as evidence-based practices (EBPs)—appear to outperform “treatment as usual” overall in head-to-head comparisons; however, the magnitude of clinical effect is attenuated when the study characteristics more closely approximate the circumstances of typical service settings (Baker, McFall, & Shoham, 2009; Weisz & Gray, 2008). Helping therapists who work in typical, non-research service settings make use of scientifically supported practices requires a systematic understanding of the variables that support successful implementation. The current study examined two hypothesized predictors of treatment implementation—therapist characteristics and supervision processes—in an effectiveness study of EBPs for youth in community mental health clinics.

Therapist Characteristics

Therapist attributes are among the variables theorized to be critical when considering the dissemination and implementation of EBPs outside of the research context (Beidas, Koerner, Weingardt, & Kendall, 2011). It has been noted that therapists tasked with delivering interventions in the context of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) may differ from the typical workforce found in community mental health clinics (Persons & Silberschatz, 1998; Weisz & Gray, 2008). Only a handful of studies in the evidence base employed any practicing therapists as treatment providers (Weisz, Doss, & Hawley, 2005; Hoagwood, Burns, Kiser, Ringeisen, & Schoenwald, 2001). The majority of RCTs use experienced, highly-trained therapists, or highly motivated graduate students who are trained by the treatment developer and receive expert supervision and immediate feedback (Weisz & Gray, 2008). In contrast, community therapists vary widely in degree of specialized training and access to expert supervision or evaluative feedback (Glisson et al., 2008;Weisz & Addis, 2006). Categorizing unique qualities of community therapists who are able to implement EBPs, versus those who are less likely to implement these practices, may provide some indication of how EBPs can best be supported in non-research service settings. Although there are many plausible explanations for effect size differences between efficacy trials and effectiveness trials, therapist attitudes, motivation, learning history, and background are one set of variables to consider. For example, the effects of such variables could manifest in a given therapist's tendency to implement an agreed-upon service plan (as outlined by a manual or supervisor) as opposed to straying from that plan.

Characteristics such as age, professional degree, years of clinical experience, theoretical orientation and attitudes towards EBPs may all play a role in identifying therapists who are best suited to adopt evidence-based practices, and may also impact factors such as treatment integrity and, ultimately, client outcomes (Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & David, 2010). Some researchers have found that therapists with doctoral degrees had more knowledge of EBPs than their counterparts, and also held more positive attitudes towards EBPs (Ashcraft et al., 2011; Nakamura, Higa-McMillan, Okamura, & Shimabukuro, 2011), and that therapists with more clinical experience were less likely to engage in EBP trainings (Stewart, Chambless, & Baron, 2012), while those with less clinical experience were more likely to use EBPs in session (Brookman-Frazee, Haine, Baker-Ericzen, Zoffness, & Garland, 2010).

The findings from studies examining the influence of therapist characteristics on various treatment outcomes, however, call into question what role—if any—therapist characteristics play. In the adult literature, therapist training, experience, and discipline have been shown to impact outcomes in some studies (Beutler et al., 2004; Huppert et al., 2001), whereas others have found that these factors accounted for little variability in outcome (Wampold & Brown, 2005). In youth psychotherapy outcome research, therapists’ years of experience were associated with client satisfaction in one study of disruptive behavior disorders (Garland, Haine, & Boxmeyer, 2007), whereas a review of 19 treatment studies of child and adolescent depression found that age and training level did not differentially predict outcomes (Michael, Huelsman, & Crowley, 2005).

Much of the literature has focused on attitudes rather than experience. Therapists with favorable attitudes towards treatment manuals self-reported more frequent use of EBPs in one study (Kolko, Cohen, Mannarino, Baumann, & Knudsen, 2009); in another, therapists who reported a negative view of manual-based treatments reported less openness towards new treatments (Ashcraft et al., 2011). Therapists may be more likely to implement EBPs when they are consistent with their own theoretical orientation. Therapists who self-identified as cognitive-behavioral or behavioral were more likely to use EBPs in observed therapy sessions for youth disruptive behavior problems (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2010). Taken together, therapist characteristics may be important for some outcomes related to EBP implementation, such as who signs up for a workshop or how much a therapist elects to use EBPs in therapy, but few studies have found that therapist characteristics predict differential outcomes in studies testing the benefits of EBPs, or have looked at their role in observed EBP implementation. Successful diffusion of innovation in healthcare may require selecting the “right target audience,”—the therapists most capable of using EBPs in practice (Cain & Mittman, 2002, p. 15)—but further examination is warranted to determine the true influence of therapist characteristics on the delivery and impact of effective treatments.

Training and Supervision

In the RCTs used to determine a treatment's efficacy, the training and supervision model is usually well-defined and carefully implemented, consisting most often of comprehensive pre-service training (in which the treatment protocol and theoretical underpinnings are learned and practiced), a probationary period wherein the therapist develops a minimal level of competency, and then on-going supervision with a treatment expert who has access to the therapists’ sessions via recordings and can give evaluative feedback (Crits-Christoph et al., 1998; Henggeler, Schoenwald, Liao, Letourneau, & Edwards, 2002). In contrast, the development of new skill sets in community practice usually consists of therapist selection of pre-service trainings that offer continuing education credits, with little—if any—follow-up during implementation (Bickman, 1999; Herschell et al., 2010). A review of studies examining training in EBP from 1990 through 2008 noted that although perceived and declarative knowledge increased following such trainings, none of the trainees met proficiency standards for adherence in studies that independently rated behavior (Beidas & Kendall, 2010).

Clinical supervision in typical community practice may differ from what is routine in research trials, with standard hour-long weekly meetings often encompassing both clinical supervision and administrative management (Bickman, 1999; Garland, Hurlburt, & Hawley, 2006). Characterizations of “supervision as usual” vary: A survey of 200 directors of mental health clinics described supervision similar to the procedures used in RCTs, with weekly meetings for almost all cases, frequent live observation of sessions, and regular use of session recordings (Schoenwald et al., 2008). In contrast, 20% of therapists treating youth for child sexual abuse in community mental health clinics reported monthly supervision or no supervision at all (Kolko et al., 2009). Therapists and their supervisors treating youth for disruptive behavior disorders in publicly funded clinics reported on how thoroughly they discussed EBP practice elements during supervision meetings, from “not at all” to “thoroughly.” Both reported that “thorough” discussion of specific practices occurred rarely (Accurso, Taylor, & Garland, 2011). In sum, it seems that the quantity and quality of supervision in typical practice is variable.

Even though anecdotal examples of the critical role of coaching and supervision in EBP implementation abound within the mental health literature (Murray, Southerland, Farmer, & Bellentine, 2010; Reinke, Stormont, Webster-Stratton, Newcomer, & Herman, 2012; Woo et al., 2012), this process has not been subjected to much systematic research. An exception to this is Multisystemic Therapy (MST), one of the few scientifically supported treatments to be effectively implemented into multiple, independent service settings (Henggeler et al., 2002; Schoenwald, Sheidow, & Chapman, 2009; Schoenwald, Sheidow, & Letourneau, 2004). The MST model requires that community clinics provide, among other services, weekly consultation with an MST expert trained in a consultation protocol, booster trainings to bolster the initial five-day orientation, and regular feedback regarding therapist adherence to MST practice use during sessions. Supervision has a demonstrated impact on both therapist adherence as well as youth outcomes, with greater adherence to the MST supervision model predictive of both (Schoenwald et al., 2009).

Apart from MST, the impact of training and supervision procedures has not been well documented in practice settings. A review of 18 published studies examining supervision in psychotherapy (Wheelers & Richards, 2007) noted only one study that examined the implementation of therapeutic skills in the client session (Borders, 1990), and only one, a single case-design, that documented a relation between supervision and client outcomes (Milne, Pikington, Gracie, & James, 2003). In general, research on supervision has largely focused on relationship factors between therapist and supervisor, without explicitly examining supervisor behaviors, therapist behaviors, or the relations of either to each other or to clinical outcomes. In one study that used random assignment to evaluate the role of supervision on adherence, therapists were assigned to (a) manual only, (b) manual and web-based training, or (c) manual, didactic training, and supervision conditions (Sholomskas, Syracuse-Siewert, Rounsaville, Ball, & Nuro, 2005). The supervision condition resulted in the highest levels of adherence using behavioral observation in a role-play. In a similar vein, a study by Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez & Pirritano (2004) randomly assigned licensed substance use professionals to different conditions for learning motivational interviewing (MI). As in other studies, the therapists who attended only a two-day workshop did not meet MI proficiency standards on selected work samples, whereas those who received either additional coaching sessions, feedback, or both met MI proficiency standards at 4-month and 8-month follow-up.

In order to develop training and supervision models that promote effective practice implementation, we need to identify specific strategies that lead to changes in therapist behavior. Candidate variables associated with effective training and supervision include educational role-plays (Milne, 1982), defined as enacting or rehearsing the practice elements from either the perspective of the therapist or the client, and modeling or demonstration (Baum & Gray, 1992), which includes watching others demonstrate a strategy (Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling, & Fennell, 2009). Because it appears to be the primary method of addressing practice use in supervision meetings, discussion of practices should also be considered (Accurso et al., 2011).

Several decades of developing, testing, and refining treatments for youth have resulted in an impressive evidence base with proven efficacy under optimal conditions. The current challenge is to identify the factors that can support effective use of these practices in community practice settings (President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003; U.S. Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, 1999). In the spirit of this challenge, the current study examined the relation of therapist characteristics and supervision processes on therapist implementation of EBPs for youth with anxiety, depression, and disruptive behavior in community clinics and schools. Fifty-seven therapists employed by community mental health clinics or school mental health programs participating in a multi-site effectiveness trial (Weisz et al., 2012) were randomly assigned to receive training and supervision in EBPs for anxiety, depression, and disruptive conduct. To address the criticisms of prior trials of EBPs, care was taken to ensure that participants and study contexts were clinically representative, and not recruited or selected, and therapist report of in-session behavior was validated with observational methods (Ward et al., 2012).

Method

Participants

Therapist participants

The sample included 57 therapists from 10 different partner clinical service organizations, from Hawaii and Massachusetts, providing office- and school-based outpatient treatment. All therapist participants had been hired by and had worked in their sites before participating in our study, none was an employee of the researchers or their institutions, and all were retained regardless of demonstration of skill. Therapists delivered EBPs using either a Standard Manual or a Modular Manual, described below; there were no significant differences between these conditions on any of the therapist characteristics measured in this study. Because studies examining provider settings have documented some differences between school-based clinics and community mental health clinics (Langley, Nadeem, Kataoka, Stein, & Jaycox, 2010), we also compared therapist characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, years of experience, degree, theoretical orientation, and attitudes toward EBPs) by setting. Therapists in school settings differed from those in community mental health clinics in terms of years of experience, degree, mental health specialty, primary theoretical orientation, and licensure status.1

Characteristics of participating therapists are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 57 Participating Therapists

| Characteristic | N | School Setting (N =19) | Clinic Setting (N = 38) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N % | ||||

| Female | 48 | 84 | 16 | 84 | 32 | 84 |

| Age (M±SD)a | 41.9±10.6 | 40.4±9.9 | 42.70±11.1 | |||

| Years of clinical experience | ||||||

| (M±SD)b | 8.7±8.1 | 5.9±5.8 | 10.3±8.9 | |||

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 39 | 68 | 10 | 53 | 29 | 76 |

| Asian | 14 | 25 | 8 | 42 | 6 | 16 |

| African American | 4 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Mental health discipline | ||||||

| Social work | 22 | 39 | 5 | 26 | 17 | 47 |

| Psychology | 14 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 39 |

| Masters level counselor | 9 | 16 | 4 | 21 | 5 | 14 |

| Other | 10 | 17 | 10 | 53 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Highest degree obtained | ||||||

| Bachelor’s | 28 | 49 | 11 | 58 | 17 | 45 |

| Master’s | 18 | 32 | 8 | 42 | 10 | 26 |

| Doctoral | 11 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 29 |

| Primary theoretical orientation | ||||||

| Cognitive-Behavioral/ Cognitive/Behavioral | 24 | 42 | 14 | 74 | 10 | 26 |

| Eclectic | 15 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 40 |

| Psychodynamic | 10 | 18 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 21 |

| Family Systems | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Other | 2 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Unknown | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Licensed | 38 | 67 | 8 | 42 | 30 | 79 |

Range: 25-60

Range: 0-35

Supervisor participants

Supervisors for this sample were 12 doctoral-level consultants located at each of the study sites in Boston (N = 7) and Honolulu (N = 5) and employed as members of the research team. Ninety-two percent were women, and the sample was 51% Caucasian non-Hispanic, 33% Asian, 8% African-American, and 8% Hispanic. All supervisors received intensive training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Depression, CBT for Anxiety, and Behavioral Parent Training (BPT) for Conduct Problems prior to the start of the study, and had experience treating youth using these treatments. Supervisors co-led all the pre-study trainings and led weekly one-hour individual supervision with study therapists. Supervisors participated in two weekly one-hour conference calls with national experts in child anxiety, depression, and conduct treatment to discuss supervised cases.

Youth participants

Study therapists treated 136 youth ages seven to 13 years (M age = 10.21), a subset of a larger research sample (N = 174; Weisz et al., 2012) referred for treatment at partner agencies for primary problems related to anxiety (30.1%), depression (25.0%), and disruptive conduct (44.1%). The current study included only those randomly assigned to the EBP conditions, excluding those assigned to the usual care condition. The larger sample has been described in detail (Weisz et al., 2012); the current subset represented a similar distribution of characteristics (67.6% boys; 47.8% Caucasian non-Hispanic, 28.4% multi-ethnic, 9.7% African-American, 7.5% Hispanic, 3.0% Asian-American/Pacific Islander, and 3.6% “Other”). The most common primary inclusion diagnosis was for disruptive conduct (44.1%), followed by anxiety (30.1%), and depression (25.0%); the majority (77%) of youth had more than one diagnosis.

Measures

Evidence based practices attitudes scale

The EBPAS (Aarons, 2004) is a 15-item measure that generates four scales: appeal, requirements, openness, and divergence. Participants indicate level of agreement with each item, ranging from 0, “not at all”, to 4, “a very great extent.” Total scores can range from 0 to 4, with 4 reflecting the most positive attitude towards EBPs. Aarons (2004) assessed the EBPAS in a study of 322 therapists across various public mental health agencies. Internal consistency was good, with Cronbach's alpha ranging from .77 for the EBPAS total scale to .90 for the requirements subscale.

Consultation Record – (MATCH and Standard Versions)

Project supervisors completed a Consultation Record (Ward et al., 2012) in collaboration with therapists for each session discussed during weekly supervision meetings. This measure was designed to facilitate a structured interview between supervisor and therapist regarding their prior use (in the previous therapy session) and planned use (in the upcoming session) of activities or strategies related to the practices represented in the EBT protocols, for example “relaxation” or “problem solving.” For each practice, supervisors noted whether an EBP practice content item was covered in the prior client session or planned for the next, upcoming client session. For each EBP practice content item planned for an upcoming client session, the supervisor further indicated whether it was discussed, modeled, or role-played during the supervision meeting. Supervisors were trained on use of the measure and definitions of the terms by the study prior to the collection of data. The PIs (Weisz & Chorpita) operationalized discussion, role play, and modeling behaviors and recorded these definitions in the study supervision protocol; these were reviewed on weekly phone calls with the study supervisors, national treatment experts, and the PIs.

Data from the Consultation Record was used to determine clinician actual use during client sessions of the EBP practice elements planned in supervision. Treatment planning in the current study took into consideration the clinical response of the client, as reported weekly by the client and caregiver, and agreement between the therapist, supervisors, and national experts about the upcoming session (see Weisz et al., 2012, for a more complete description), using the prescribed treatment manual content as a guide. Thus, concordance, considered to be a “match” between the practice content item planned in supervision and the practice content item that occurred in the next session, represented adherence to the treatment implementation system.

To determine the reliability of clinician report of practice content items used in client sessions, the Consultation Records were validated using agreement with observational coding of audio or video recordings of the same session. Coders were trained to high levels of inter-coder agreement (Average ICC = .80); average agreement for session coverage between therapist report and coders was acceptable according to the standards of Cicchetti and Sparrow (1981) for both standard manual delivery (ICC = .71) and modular manual delivery (ICC = .74; Ward et al., 2012).

Procedures

Training

Therapists participated in three, two-day trainings for CBT for Anxiety and Depression and BPT for Disruptive Conduct. All therapists received identical training, and were in the same room at the same tables at the same time. Most of the training was spent discussing the theoretical framework of the EBPs for each disorder and role-playing various treatment techniques. Training sessions were organized by skills (i.e. behavioral exposure or a time-out procedure) and each event covered nine to 12 skills.

Treatment

Therapists met with youths who were referred to their clinic for treatment. Youths were randomly assigned to therapists in the two EBP conditions (Standard Manual and Modular Manual), as well as to usual care therapists (not included in these analyses). In the Standard Manual condition, therapists used three manuals that were representative of (and included the common core elements of) CBT for anxiety, CBT for depression, and BPT for youth conduct problems: Coping Cat (Kendall, 1994; Kendall, Kane Howard, & Siqueland, 1990), Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training (PASCET; Weisz, Thurber, Sweeney, Proffitt, & LeGagnoux, 1997; Weisz et al., 2005), and Defiant Children (Barkley, 1997). In the Modular Manual condition, therapists used a trans-diagnostic treatment protocol, Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, and Conduct Problems (MATCH-ADC; Chorpita & Weisz, 2005). MATCH-ADC included modules for core treatment elements that systematic reviews had found to be most common in CBT for anxiety, CBT for depression, and BPT for youth conduct problems; the MATCH modules functionally correspond to the treatment procedures included in Coping Cat, PASCET, and Defiant Children. All therapy sessions were audio- or video-recorded.

Supervision

Therapists met weekly for one-hour of individual supervision with their assigned supervisor. On average, therapists and supervisors met 18.2 times per treatment case. Supervision was face-to-face, at the therapists’ service setting. During the meetings, supervisors reviewed and recorded (a) events that happened prior to the preceding therapy session, such as client homework completion; (b) events that took place during the preceding therapy session, including the EBP practices that had been implemented, the child or caregiver's understanding of the treatment content, and the use of homework assignments, behavioral rehearsal, or in-vivo activities during the session; and (c) events that occurred during the supervision meeting, including discussion, live modeling, or role-playing of specific EBP practices; and (d) what EBP practices were planned for the upcoming session. When possible, supervisors reviewed session recordings prior to meeting therapists.

Results

The first set of analyses examined whether therapist characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, years of experience, degree, theoretical orientation, and attitudes toward EBPs) predicted the main study outcome: overall percentage of concordance between planned and subsequently reported practices, relative to total number of sessions. Univariate regression analyses separately modeled the percentage of concordance for each client case, predicted by each of the therapist characteristics. None of the therapist characteristics emerged as significant predictors of overall content matches in session. This model, and all the non-significant predictor models, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Univariate regression models for practice concordance predicted by therapist characteristics.

| Predictor Variable | β | se | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapist Age | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.08 | .281 |

| Therapist Sex | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.08 | .937 |

| Therapist Ethnicity | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.31 | .755 |

| Years of Experience | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.10 | .276 |

| Therapist Degree | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.96 | .339 |

| Theoretical Orientation | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.42 | .677 |

| Attitudes towards EBPs | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.56 | .576 |

Univariate regression analyses were also performed to examine the relation of supervision processes (discussion of planned content, modeling of planned content, or role-play of planned content) on the overall percentage of session practice concordance, controlling for the number of supervision meetings. Modeling (β = 0.28, t = 2.70, p = .008, r2 = 0.10) and role-play (β = 0.22, t = 2.49, p = .014, r2 = 0.09) in supervision meetings significantly predicted increased practice concordance; the relation between discussion of content in supervision and practice concordance in session was not significant (β = -0.11, t = -0.74, p = .458, r2 = 0.05).

To further investigate the explanatory power of supervision processes, the effects of supervision processes on the immediately following therapy session were examined for clients over the course of treatment, modeling the probability of a match between planned and executed content in the session, using HLM version 6.08 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004). To manage the dichotomous variable, we used a Bernoulli sampling model and a logit-link to examine the relation of each prior session supervision procedure to future content match. Intraclass correlations as calculated from an empty (i.e., random intercept only) model were .93 for matches, suggesting that most of the variance for content matching occurred between persons and was not accounted for by time. Preliminary analyses suggested that a fixed effects model for the likelihood of content match at level 2 had acceptable fit; thus all conditional models were examined using that structure as a baseline. Modeling practices in supervision significantly predicted practice concordance in the immediate next session (β = 1.02, t = 7.84, p < 0.001, OR = 2.77). Practice concordance was not significantly predicted by discussion of practice elements in supervision (β = -0.01, t = -0.39, p = 0.70, OR = 0.99) or by role-play (β = -0.01, t = -0.84, p = 0.43, OR = 0.99) in the immediately prior supervision meeting.

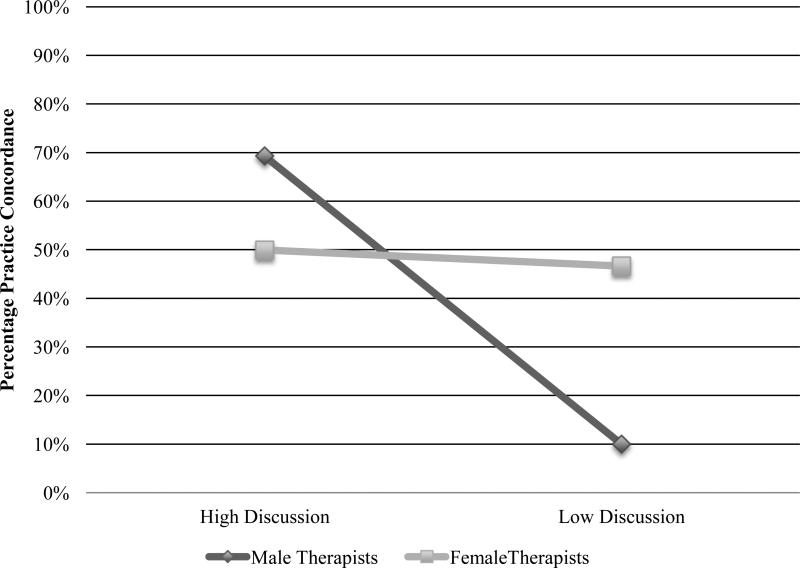

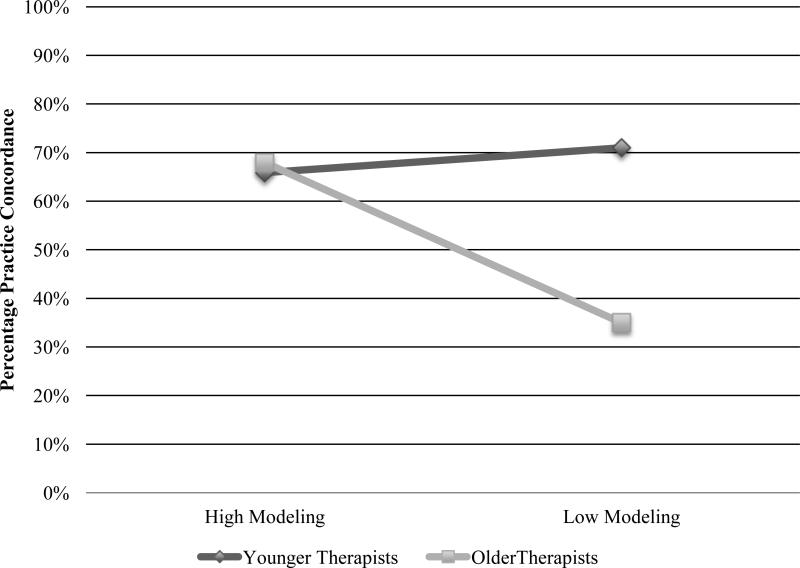

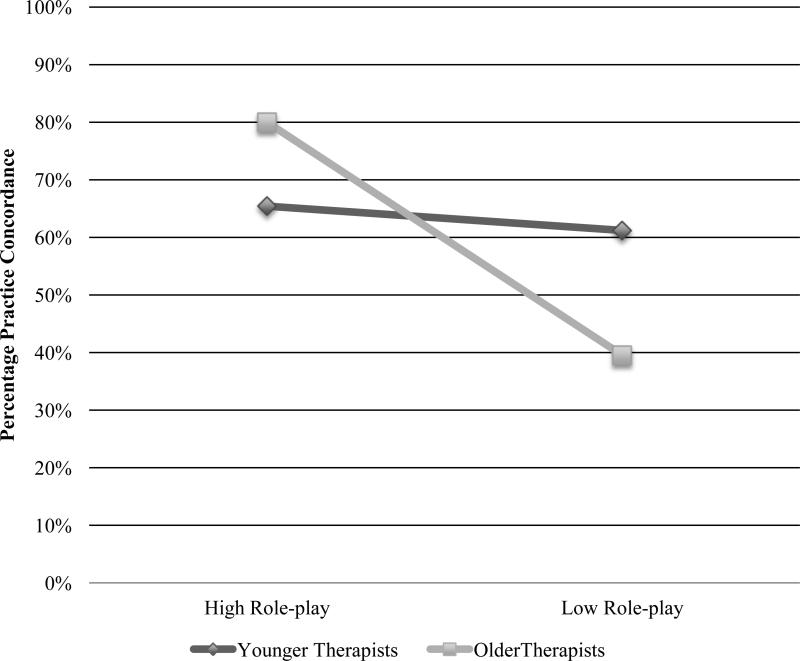

To test whether the therapist characteristics moderated the relation of supervision processes and EBP concordance, each supervision process (Discussion, Modeling, Role-play), therapist characteristic (Age, Degree, Years of Clinical Experience, Attitudes toward EBTs, Primary Theoretical Orientation), and their interactions were entered into separate linear regression models, controlling for total number of supervision meetings (Baron & Kenny, 1986). To correct for multiple comparisons, we used The interaction of therapist sex and discussion of planned content was significant (β = 0.43, t = 2.14, p = .034, r2 = 0.08); follow-up analyses completed separately by sex demonstrated that discussion in supervision predicted content match for male therapists (β = 1.25, t = 3.15, p = .007, r2 = 0.46), but not for female therapists (β = -0.27, t = - 1.73, p = .087, r2 = 0.06). These interactions are illustrated in Figure 1. The interaction of therapist age and modeling was significant (β = 0.96, t = 2.47, p = .015, r2 = 0.16), and therapist age and role-play approached significance (β = 0.74, t = 1.80, p = .074, r2 = 0.13). Simple slope analyses probed the form of significant interactions at 1 SD (10.61) above and below the mean of the moderator, age (M = 41.91) following Aiken and West (1991). For older therapists (> 53 years of age), modeling (β = 1.11, t = 5.67, p < .001, r2 = 0.73) and role-play (β = 0.85, t = 5.68, p < .001, r2 = 0.73) in supervision meetings predicted content matches in session, whereas neither modeling (β = 0.81, t = 0.32, p = .755, r2 = 0.00) nor role-plays (β = 0.04, t = 0.02, p = .984, r2 = 0.00) were significant predictors for younger (< 31 years of age) therapists. Mean concordance for older therapists (M = 59.82%) and younger therapists (M = 52.31%) did not differ significantly. These interactions are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Therapist sex moderates the relation of supervision discussion and practice concordance in session.

Figure 2.

Therapist age moderates the relation of supervision modeling and practice concordance in session.

Figure 3.

Therapist age moderates the relation of supervision role-play and practice concordance in session.

Discussion

Increasing the use of EBPs by community therapists to improve mental health care for youth requires a firm understanding of the processes that support their effective application. Possible explanations for the decreased benefit of practices, sometimes seen in service settings relative to research trials, have included the heterogeneity of therapists in typical practice on a number of demographic, professional, and philosophical characteristics (Weisz & Gray, 2008). It is also possible that supervision processes play a role in effective EBP implementation. The current study examined whether therapist characteristics, supervision processes, and the interaction of these factors predicted the use of planned EBPs in treatment sessions. As has been noted, ensuring that therapist EBP skills and techniques are used with fidelity is critical to a clearer understanding of whether practices are beneficial, and under what conditions this benefit can be maximized (Schoenwald, Garland, Southam-Gerow, Chorpita, & Chapman, 2011).

In the current study, we measured one type of treatment adherence: congruence, or “match” between the EBP element planned in supervision meetings with supervisors and the actual use of the practice element in session. This differs somewhat from the typical measurement of treatment adherence, in which the content of a session is evaluated in terms of how well it approximates the content described in the treatment protocol (Schoenwald et al., 2010). Supervisors in the current study generally recommended the use of practices delineated in the EBP protocols and the sequence of practice elements indicated by the EBP programs. However, therapists and supervisors also received weekly input about client progress from the youth and caregiver, and specific practice recommendations from national treatment experts. Therefore, the execution of the weekly supervision “plan” as agreed upon by the therapist and the supervisor represented adherence to the overall treatment system used in this study, and appears to fit the APA definition of EBP as “the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture, and preferences,” (2001, p.1).

We examined both therapist characteristics and processes that occurred in supervision meetings to determine their relation to planned practice use. Despite research suggesting that therapist degree, clinical experience, and attitudes towards EBPs may be related to use of EBPs (Ashcraft et al., 2011; Nakamura et al., 2011; Nelson & Steele, 2007; Stewart et al., 2012), in this study no therapist characteristic emerged as a predictor of the match between planned and implemented practices, and therapists’ practice use in session was concordant more than half of the time (57%). This bodes well for efforts to increase EBP use among community therapists, given that the front-line work force will vary widely with regard to variables such as training, degree, years of experience, and theoretical orientation (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2009; Kolko et al., 2009). The current study suggests that therapists who vary along these dimensions may be equally capable of delivering EBP practice elements as planned in supervision.

Additionally, we assessed the cumulative and immediate impact of supervision processes hypothesized to be associated with therapist practice use in session. Overall, the supervision strategies that predicted greater concordance were the use of supervisor modeling practices and use of therapist-enacted role-plays. Discussion of practices did not predict whether those practices occurred. The same variables were examined in terms of their immediate impact: modeling of practices in supervision predicted concordance in the session that immediately followed, whereas discussion and role-play did not predict greater concordance in the next session. Although role-play in supervision appears to increase the likelihood that therapists will use EBP practices in session over the course of treatment, perhaps the observation of expert modeling is most essential to EBP use in the immediate future. Innovative presentations of expert demonstration, such as via multimedia online training demonstrations, may be a useful, low-cost way to influence practice behaviors of therapists in community practice settings (Dimeff et al., 2009; Ruzek & Rosen, 2009).

Supervision processes such as focused discussion, expert demonstration, and therapist behavioral rehearsal of practices may be commonplace in efficacy trials; in practice settings, supervision may vary in terms of time and attention paid to administrative tasks, discussion of practices, and active learning strategies (Accurso et al., 2011; Bickman, 1999; Schoenwald et al., 2009). There is a growing evidence base supporting the use of active learning strategies to augment the traditional training structure of continuing education workshops (Baum & Gray, 1992; Miller & Mount, 2001). This study supports the use of these same strategies in ongoing community practice supervision in order to increase the likelihood that practices will be executed in session as planned. This dovetails with a recent review of empirical studies suggesting that educational role-play and modeling should be considered supported methods of supervision (Milne, Sheikh, Pattison, & Wilkinson, 2011). It is also consistent with survey research examining the development of skills among CBT therapists (Bennett-Levy et al., 2009), and with experiential learning educational models (Kolb, 1984).

The relation of supervision processes on EBP use in session may vary with certain therapist characteristics. In this sample, discussion of EBP practices predicted use of those practices for male therapists, but not for female. The implications of this result are unclear; male and female therapists in this study did not significantly differ in terms of age, years of experience, level of degree, or primary theoretical orientation. There were significant ethnic differences between the samples of male and female therapists, with more female therapists (75%) than male therapists (33%) who identified as Caucasian, non-Hispanic. The vast majority of therapists in our study were women, who saw 80% of the cases in this sample, as in similar studies of child and adolescent mental health therapists (Garland et al., 2010; Kolko et al., 2009). Such a small sample of cases with male therapists (N = 18) limits our confidence in this finding.

Discussion of practice elements appears to be a common part of “supervision as usual,” (Accurso et al., 2011); modeling and role-playing may be less typical, but were especially potent predictors of planned practice use for older therapists. Although years of clinical experience did not moderate the effect of supervision processes on concordance, it is possible that older therapists may be less familiar with EBPs, and therefore benefit from the opportunity to see demonstrations or to rehearse in supervision. Other studies have likewise found differences in therapist attitudes towards EBPs and use of EBPs indicating that less experience, or closer proximity to formal training, may result in more willingness to use EBPs (Brookman-Frazee, et al., 2010; Stewart et al., 2012). Perhaps active learning strategies are less crucial with these types of therapists relative to their older colleagues.

The promise of practices that have been found effective is predicated on the actual delivery of these practices in the service settings; identifying the variables that foster EBP use is therefore an important step in services research. Nonetheless, several limitations of the research must be acknowledged. All of the therapists in the current study volunteered to participate in the RCT of EBPs at their site, and may differ from those who did not volunteer, particularly in terms of their willingness to use EBPs. Nonetheless, the therapists who participated in this project were employees in community service settings and represented a broad continuum in terms of age, degree, theoretical orientation and attitudes towards EBPs. Secondly, while implementation of planned content is an important part of treatment integrity, this study did not measure the skillfulness with which practice elements were delivered. Therapist competency with EBPs is another variable that may differ between typical practice and research-based trials, and may play a part in the attenuation of effects as treatments move from research into practice (Fairburn & Cooper, 2011). Finally, this study did not randomly assign supervisors or therapists to conditions that manipulated the supervision processes of interest, such as discussion, modeling, or role-play. A trial that used an experimental design to examine the role of these supervision processes and practice concordance would increase confidence in the causal relations of these variables.

This study used therapist report of in-session behaviors as a measure of practices implemented in session, and therapists in this study demonstrated acceptable agreement with observational coders regarding the presence and absence of practice content items. However, it is important to view this within the parameters of the current study: therapists discussed the sessions at length with expert study consultants, and in the presence of session recordings. Accordingly, while we are confident in the reliability of therapist report in the current study, the reliability of therapist self-report in the absence of these conditions is not known, and has been found to be discordant with observational coding in another study of in session behavior (Hurlburt et al., 2010). The fact that therapy sessions in this study were recorded may have inflated the rate of therapist adherence with the supervision plan; future studies should consider other ways of measuring standard practice, such as random “work samples.”

In this study, supervisors were research staff and were fairly homogenous in terms of degree, professional specialty, primary theoretical orientation, and years of experience. This study did not measure supervisor variables, such as adherence to supervision, or clinician development, that have been found to predict therapist and client behaviors in other studies (Schoenwald et al., 2009). Future studies should consider the role that supervisor characteristics, and the alliance between the therapist and supervisor, may play in determining therapist behavior as well as other indicators of EBP implementation.

Despite these caveats, the results of this study have important implications for the up-scaling of effective practices in service settings. Therapists of varying age, degrees, experience, theoretical orientations, and attitudes towards EBPs can deliver these practices in session as planned. Additionally, the supervision processes related to practice execution are modifiable, can be systematically included in efforts to support the use of EBPs in practice settings, and may be especially helpful for older therapists. Given that clinical supervision has been judged a “core professional competency” for the mental health field (Falender et al., 2004), identifying the specific aspects that impact therapist behavior could inform efforts to standardize its application and increase the availability of effective, evidence-based treatments for youth outside the context of research settings. There is increasing evidence that didactic trainings without behavioral rehearsal or ongoing support are not sufficient to change therapist behavior (Beidas & Kendall, 2010); the current study suggests that modeling and role-play may be two important behaviors to include in training and supervision of EBPs, and that therapists in community practice are able to implement these EBP practices.

Acknowledgments

The Research Network on Youth Mental Health is a collaborative network funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Network Members at the time this work was performed included: John Weisz, Ph.D. (Network Director), Bruce Chorpita, Ph.D., Robert Gibbons, Ph.D., Charles Glisson, Ph.D., Evelyn Polk Green, M.A., Kimberly Hoagwood, Ph.D., Kelly Kelleher, M.D., John Landsverk, Ph.D., Stephen Mayberg, Ph.D., Jeanne Miranda, Ph.D., Lawrence Palinkas, Ph.D., and Sonja Schoenwald, Ph.D. This manuscript was presented at the annual convention of the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies in November, 2011, Toronto, Canada.

Footnotes

We explored whether provider setting predicted the main study outcome: overall percentage of concordance between planned and subsequently reported EBP use, relative to total number of sessions in a univariate regression model. Provider setting did not predict planned EBP use in session (β = 0.47, t = 1.08, p = .281, r2 = 0.009), nor did provider setting moderate the relations between supervision processes and planned EBP use.

Contributor Information

Sarah Kate Bearman, Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology, Department of School-Clinical Child Psychology, Yeshiva University.

John R. Weisz, Department of Psychology, Harvard University.

Bruce F. Chorpita, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Kimberly Hoagwood, The Child Study Center, New York University.

Alyssa Ward, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Ana M. Ugueto, Department of Psychology, Harvard University.

Adam Bernstein, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- Aarons G. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services. 2004;6:61–74. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000024351.12294.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Sommerfeld DH, Hecht DB, Silovsky JF, Chaffin MJ. The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: Evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:270–280. doi: 10.1037/a0013223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accurso EC, Taylor RM, Garland AF. Evidence-based practices addressed in community-based children's mental health clinical supervision. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 2011;5:88–96. doi: 10.1037/a0023537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME, Krasnow AD. A national survey of practicing psychologists’ attitudes toward psychotherapy treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:331–339. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Policy Statement on Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology. 2001 Available online at http://www2.apa.org/practice/ebpstatement.pdf.

- Ashcraft RP, Foster SL, Lowery AE, Henggeler SW, Chapman JE, Rowland MD. Measuring practitioner attitudes toward evidence-based treatments: A validation study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2011;20:166–183. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, McFall RM, Shoham V. Current status and future prospects of clinical psychology: Toward a scientifically principled approach to mental and behavioral health. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;9:4–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Defiant children: A clinician's manual for assessment and parent training. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY US: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable Distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;61:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum BE, Gray JJ. Expert modeling, self-observation using videotape, and acquisition of basic therapy skills. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1992;23:220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Koerner K, Weingardt KR, Kendall PC. Training research: Practical recommendations for maximum impact. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:223–237. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0338-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett-Levy J, McManus F, Westling BE, Fennell M. Acquiring and refining CBT skills and competencies: Which training methods are perceived to be most effective? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;37:571–583. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809990270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE, Malik ML, Alimohamed S, Harwood TM, Talebi H, Noble S. Therapist variables. In: Lambert MJ, et al., editors. Bergin and Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. 5th ed. Wiley; New York: 2004. pp. 227–306. [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. Practice makes perfect and other myths about mental health services. American Psychologist. 1999;54:965–978. [Google Scholar]

- Borders LD. Developmental changes during supervisees’ first practicum. Clinical Supervisor. 1990;8:157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Haine RA, Baker-Ericzen M, Zoffness R, Garland AF. Factors associated with use of evidence-based practice strategies in usual care youth psychotherapy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:254–269. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain M, Mittman R. Diffusion of innovation in health care. California HealthCare Foundation; 2002. Available via California HealthCare Foundation. http://www.chcf.org/publications/2002/05/diffusion-of-innovation-in-health-care. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Ebesutani C, Young J, Becker KD, Nakamura BJ, Phillips L, Ward A, Lynch R, Trent L, Smith R, Okamura K, Starace N. Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness.Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18:154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Weisz JR. Modular approach to therapy for children with anxiety, depression, or conduct problems. University of Hawaii at Manoa and Judge Baker Children's Center, Harvard Medical School; Honolulu and Boston: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetii DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1981;86:127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Chittams J, Barber JP, Beck AT, Frank A, Liese B, Luborsky L, Mark D, Mercer D, Onken LS, Najavits LM, Thase ME, Woody G. Training in cognitive, supportive-expressive, and drug counseling therapies for cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:484–492. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis NM, Ronan KR, Borduin CM. Multisystemic Treatment: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:411–419. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Koerner K, Woodcock EA, Beadnell B, Brown MZ, Skutch JM, et al. Which training method works best? A randomized controlled trial comparing three methods of training clinicians in dialectical behavior therapy skills. Behavioural Research and Therapy. 2009;47:921–930. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. Therapist competence, therapy quality, and therapist training. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falender CA, Cornish J, Goodyear R, Hatcher R, Kaslow NJ, Leventhal G, Grus C. Defining Competencies in Psychology Supervision: A Consensus Statement. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;60:771–785. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Brookman-Frazee L, Hurlburt MS, Accurso EC, Zoffness RJ, Haine-Schlagel R, Ganger B. Mental health care for children with disruptive behavior problems: A view inside therapists’ offices. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:1–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Haine RA, Boxmeyer CL. Determinates of youth and parent satisfaction in usual care psychotherapy. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2007;30:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hurlburt MS, Hawley KM. Examining psychotherapy processes in a services research context. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK, Kelleher K, Landsverk J, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S, Green P. Therapist turnover and new program sustainability in mental health clinics as a function of organizational culture, climate, and service structure. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35:124–133. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ. Multisystemic treatment of substance-abusing and –dependent delinquents: Outcomes, treatment, fidelity, and transportability. Mental Health Services Research. 1999;1:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022373813261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Liao JG, Letourneau EJ, Edwards DL. Transporting efficacious treatments to field settings: The link between supervisory practices and therapist fidelity in MST programs. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2002;31:155–167. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, David AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Kiser L, Ringeisen H, Schoenwald SK. Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1179–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert JD, Bufka LF, Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW. Therapists, therapist variables, and cognitive-behavioral therapy outcome in a multicenter trial for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:747–755. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt M, Garland A, Nguyen K, Brookman-Frazee L. Child and family therapy process: Concordance of therapist and observational perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:230–244. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0251-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:100–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Kane M, Howard B, Siqueland L. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of anxious children: Treatment manual. Workbook Publishing; Ardmore, PA.: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb DA. Experiential Learning. Prentice-Hall; New Jersey: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Baumann BL, Knudsen K. Community treatment of child sexual abuse: A survey of practitioners in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36:37–49. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley AK, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH. Evidence-based mental health programs in schools: Barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. School Mental Health. 2010;2:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9038-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael KD, Huelsman TJ, Crowley SL. Interventions for child and adolescent depression: Do professional therapists produce better results? Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Mount KA. A small study of training in motivational interviewing: Does one workshop change clinician and client behaivor? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moters TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne DL. A comparison of two methods of teaching behaviour modification to mental handicap nurses. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1982;10:54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Milne D, Pilkington J, Gracie J, James I. Transferring skills from supervision to therapy: A qualitative and quantitative N = 1 analysis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2003;31:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Milne DL, Sheikh AI, Pattison S, Wilkinson A. Evidence-based training for clinical supervisors: A systematic review of 11 controlled studies. The Clinical Supervisor. 2011;30:53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Murray MM, Southerland D, Farmer EM, Ballentine K. Enhancing and adapting treatment foster care: Lessons learned in trying to change practice. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:393–403. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9310-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura BJ, Higa-McMillan CK, Okamura KH, Shimabukuro S. Knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence-based practices in community child mental health practitioners. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2011;38:287–300. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TD, Steele RG. Predictors of practitioner self-reported use of evidence-based practices: Practitioner training, clinical setting, and attitudes toward research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Treat TA, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity in psychotherapy research: Analysis of the studies and examination of the associated factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:829–841. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persons J, Silberschatz G. Are results of randomized clinical trials useful to psychotherapists? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:126–135. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health . Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2003. Final Report (DHHS Pub. No. SMA-03-3832) [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM (Version 6.08) [Computer software] Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke WM, Stormont M, Webster-Stratton C, Newcomer LL, Herman KC. The Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management Program: Using coaching to support generalization to real-world classroom settings. Psychology in the Schools. 2012;49:416–428. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzek JI, Rosen RC. Disseminating evidence-based treatments for PTSD in organizational settings: A high priority focus area. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Garland AF, Chapman JE, Frazier SL, Sheidow AJ, Southam Gerow MA. Toward the effective and efficient measurement of implementation fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;38:32–43. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Garland AF, Southam-Gerow MA, Chorpita BF, Chapman JE. Adherence measurement in treatments for disruptive behavior disorders: Pursuing clear vision through varied lenses. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18:331–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01264.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Kelleher K, Weisz J, The Research Network on Youth Mental Health Building bridges to evidence-based practice: The MacArthur Foundation Child System and Treatment Enhancement Projects (Child STEPs). Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35:66–72. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow AJ, Chapman JE. Clinical supervision in treatment transport: effects on adherence and outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:410–421. doi: 10.1037/a0013788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow AJ, Letourneau EJ. Toward effective quality assurance in evidence-based practice: Links between expert consultation, therapist fidelity, and child outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:94–104. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF. We don't train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training therapists in cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RE, Chambless DL, Baron J. Theoretical and practical barriers to practitioners’ willingness to seek training in empirically supported treatments. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68:8–23. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General . Mental health: A report of the surgeon general. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Brown GS. Estimating variability in outcomes attributable to therapists: A naturalistic study of outcomes in managed care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:914–923. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A, Regan J, Chorpita B, Starace N, Rodriguez A, Okamura K, Daleiden E, Bearman SK, Weisz J. Tracking Evidence-Based Practice with Youth: Validity of the MATCH and Standard Manual Consultation Records. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.700505. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR. Psychotherapy for children and adolescents: Evidence-based treatments and case examples. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Addis ME. The research-practice tango and other choreographic challenges: Using and testing evidence-based psychotherapies in clinical care settings. In: Goodheart CD, Kazdin AE, Sternberg RJ, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapy: Where practice and research meet. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC US: 2006. pp. 179–206. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman S, Gibbons RD. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:274–282. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Doss AJ, Hawley KM. Youth psychotherapy outcome research: A review of critique of the evidence base. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:337–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Gray JS. Evidence-based psychotherapy for children and adolescents: Data from the present and a model for the future. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2008;13:54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM. Evidence-based youth psychotherapies versus usual clinical care: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. American Psychologist. 2006;61:671–689. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Moore PS, Southam-Gerow MA, Weersing VR, Valeri SM, McCarty CA. Therapist's Manual PASCET: Primary and secondary control enhancement training program. 3 ed. University of California; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Thurber CA, Sweeney L, Proffitt VD, LeGagnoux GL. Brief treatment of mild-to-moderate child depression using primary and secondary control enhancement training. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:703–707. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S, Richards K. The impact of clinical supervision on counselors and therapists, their practice and their clients. A systematic review of the literature. Counseling and Psychotherapy Research. 2007;7:54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Woo SM, Hepner KA, Gilbert EA, Osilla K, Hunter SB, Muñoz RF, Watkins KE. Training addiction counselors to implement an evidence-based intervention: Strategies for increasing organizational and provider acceptance. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.03.004. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]