Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the accuracy of the amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct (AMTD) test with reference methods for the laboratory diagnosis of tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients.

METHODS:

This was a study of diagnostic accuracy comparing AMTD test results with those obtained by culture on Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium and by the BACTEC Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube 960 (BACTEC MGIT 960) system in respiratory samples analyzed at the Bioassay and Bacteriology Laboratory of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation Evandro Chagas Clinical Research Institute in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

RESULTS:

We analyzed respiratory samples collected from 118 patients, of whom 88 (74.4%) were male. The mean age was 36.6 ± 10.6 years. Using the AMTD test, the BACTEC MGIT 960 system, and LJ culture, we identified M. tuberculosis complex in 31.0%, 29.7%, and 27.1% of the samples, respectively. In comparison with LJ culture, the AMTD test had a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of 87.5%, 89.4%, 75.7%, and 95.0%, respectively, for LJ culture, whereas, in comparison with the BACTEC MGIT 960 system, it showed values of 88.6%, 92.4%, 83.8%, and 94.8%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

The AMTD test showed good sensitivity and specificity in the population studied, enabling the laboratory detection of M. tuberculosis complex in paucibacillary respiratory specimens.

Keywords: Molecular diagnostic techniques, Tuberculosis, HIV, Molecular probe techniques

Introduction

Even though more than a century has passed since the discovery of the etiologic agent of tuberculosis, i.e., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the disease remains a public health problem worldwide. Each person with active tuberculosis will infect between 10 and 15 people every year. ( 1 ) It is estimated that at least one of every 10 people who have come in contact with the tuberculosis bacillus will develop the disease and that, in HIV-infected patients, this risk is 20 to 40 times higher.( 2 ) Studies evaluating survival in patients with tuberculosis/HIV co-infection have shown that the risk of death is higher in these patients than in HIV-infected patients without tuberculosis.( 3 - 6 )

Mycobacterial culture on solid Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium is considered the gold standard isolation method.( 7 ) Although the limitation of this method is the long incubation period (2-8 weeks), it is used by most developing countries because of its low cost. Techniques such as nucleic acid amplification and automated liquid culture systems are costly and depend on sophisticated tools, which prevents their routine use in poor countries.

In the last decade, laboratory tests for detection of M. tuberculosis have evolved considerably.( 8 ) Today we have new methods, such as GeneXpert (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), which can yield results in 2 h, detecting M. tuberculosis complex and determining whether the strains are rifampin resistant; however, this method remains costly and has just begun to be used and validated for use in Brazil. The amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct (AMTD) test (Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA, USA) can detect M. tuberculosis complex rRNA in approximately 3 h. This test was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in smear microscopy-positive respiratory samples in 1995, and, after it was improved in 1999, it was approved for use in smear microscopy-negative samples.( 9 ) There is still need for a better understanding of the performance of this test for paucibacillary patients, such as HIV-infected patients in Brazil, since the quality of their samples makes it difficult to establish a laboratory diagnosis, even by gold standard methods, such as liquid culture. The objective of the present study was to compare the diagnostic accuracy of the AMTD test with other culture methods in respiratory samples collected from HIV-infected patients, by means of a study under real-life routine conditions in a mycobacteriology laboratory.

Methods

This was a study of diagnostic accuracy, conducted under routine conditions at the bacteriology laboratory of the Evandro Chagas Clinical Research Institute, which is a referral center for the treatment of infectious diseases, located in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. All respiratory samples provided by HIV-infected patients suspected of having pulmonary tuberculosis and sent to the laboratory between January of 2008 and June of 2009 were included in the study. All samples collected from the same patient subsequent to the first sample were excluded from the study. Respiratory samples included sputum, induced sputum, and bronchoalveolar lavage samples.

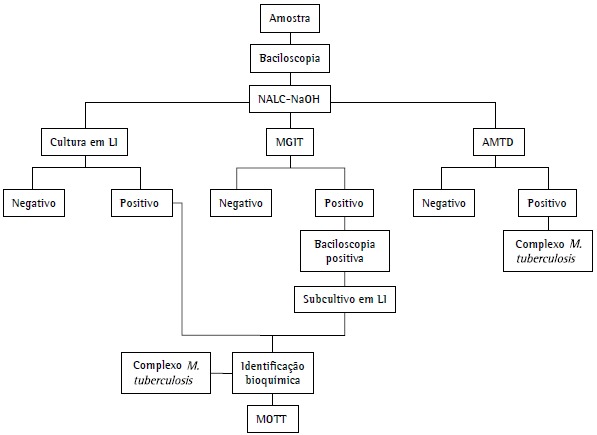

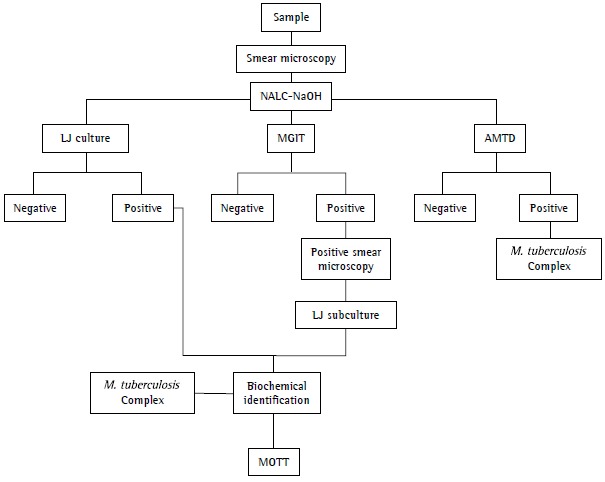

The clinical specimens were processed as shown in Figure 1. The samples were analyzed by smear microscopy, LJ culture, and the BACTEC Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube 960 (BACTEC MGIT 960) system (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA). Smear microscopy was performed on the same day the clinical specimen was received at the laboratory. In contrast, cultures were performed over the course of 2 days at most. The samples showing growth on LJ medium, through culture or through subculture of positive BACTEC MGIT 960 cultures, were sent for biochemical identification of M. tuberculosis complex (detection of niacin production, nitrate reduction, and thermal inactivation of catalase).( 10 ) In the present study, cultures that produced niacin, reduced nitrate to nitrite, and showed inactivation of catalase at 68ºC were identified as positive for M. tuberculosis complex. Different results from those described above were analyzed and defined as positive for mycobacteria other than tuberculosis (MOTT). Part of the pellet obtained from decontamination of the samples was sent for AMTD tests and subsequent interpretation of results and for incubation in the BACTEC MGIT 960 system. Both methods were carried out as described by the respective manufacturers.( 11 , 12 ) A positive result was defined as the presence of M. tuberculosis complex in the sample, and a negative result was defined as the absence of M. tuberculosis complex. The AMTD test was performed weekly, and biochemical identification was obtained in the same week the cultures or subcultures yielded positive results. All collaborators who performed the tests mentioned above are regularly trained and evaluated on these procedures. There was no blinding of the collaborators, since they were performing routine tests.

Figure 1. Sample processing flowchart. NALC-NaOH: N-acetyl-L-cysteine-sodium hydroxide; LJ: Löwenstein-Jensen; MGIT: Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube; AMTD: amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct (test); and MOTT: mycobacteria other than tuberculosis.

The outcomes of interest were sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy, likelihood ratio (LR), and respective 95% CIs. These measures were calculated using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and WINPEPI, version 11.15 (http://www.brixtonhealth.com/pepi4windows.html).

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Evandro Chagas Clinical Research Institute (Protocol no. 0002.0.009.000-11) and was developed in accordance with the recommendations of the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy.( 13 )

A letter about the present study has been published.( 14 )

Results

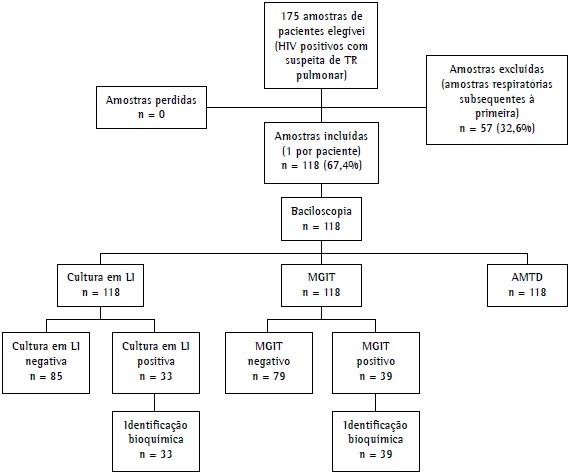

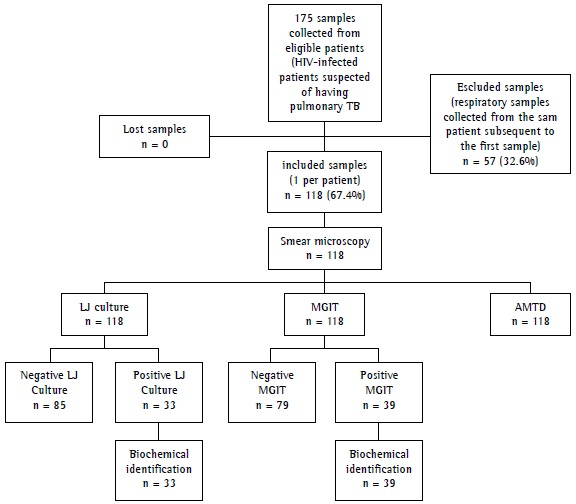

Of the 175 samples eligible for the study, 57 were excluded because they were subsequent samples from the same patient. Therefore, we analyzed the first respiratory samples collected from 118 patients, of whom 88 (74.4%) were male. The mean age was 36.6 ± 10.6 years. The results of all tests performed were conclusive. Figure 2 shows the study processing flowchart.

Figure 2. Study design diagram. TB: tuberculosis; LJ: Löwenstein-Jensen; MGIT: Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube; and AMTD: amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct (test).

Of the 118 samples analyzed, 16 (13.6%) had positive results by smear microscopy. Of those 118 samples, 33 (27.9%) were positive by LJ culture, 1 of which was identified as MOTT, whereas (33.1%) were positive by the BACTEC MGIT 960 system, 3 of which were identified as MOTT and 1 of which was identified as Rhodococcus spp. The AMTD test detected 37 positive samples (31.4%) for M. tuberculosis complex. The isolated MOTT and Rhodococcus spp. strains were excluded from the main analysis because they are not targeted by the method under analysis.

After exclusion of those 5 samples, the comparison of the AMTD test results with those obtained by LJ culture showed that there were four false-negative results and nine false-positive results, whereas the comparison of the AMTD test results with those obtained by the BACTEC MGIT 960 system showed that there were six false-positive results and four false-negative results. Table 1 shows the diagnostic accuracy of the AMTD test in comparison with LJ culture and with the BACTEC MGIT 960 system.

Table 1. Accuracy of the amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test relative to culture on Löwenstein-Jensen medium and to the BACTEC Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube 960 system.a.

| Variable | AMTD vs. LJ | AMTD vs. MGIT |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 87.5 (71.0-96.5) | 88.6 (73.3-96.8) |

| Specificity | 89.4 (80.8-95.0) | 92.4 (84.2-97.2) |

| Positive predictive value | 75.7 (58.8-88.2) | 83.8 (68.0-93.8) |

| Negative predictive value | 95.0 (87.7-98.6) | 94.8 (87.2-98.6) |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 8.25 (4.39-15.54) | 11.66 (5.35-25.40) |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.14 (0.06-0.35) | 0.12 (0.05-0.31) |

| Accuracy | 88.9 (81.7-93.9) | 91.2 (84.5-95.7) |

: amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct (test)

: Löwenstein-Jensen

: Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube

Values expressed as % (95% CI).

In comparison with the BACTEC MGIT 960 system, the AMTD test had a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPP of 88.6%, 92.4%, 83.8%, and 94.8%, respectively, whereas, in comparison with LJ culture, it showed values of 87.5%, 89.4%, 75.7%, and 95.0%, respectively. These results, together with their 95% CIs, the LRs, and the accuracy values, are shown in Table 1.

The same parameters were calculated for a subgroup of smear microscopy-negative samples, although that was not part of the initial analysis plan. The following results were obtained: sensitivity, 70.8% (95% CI: 48.6-87.3); specificity, 94.8% (95% CI: 87.2-98.6); PPV, 81.0% (95% CI: 58.1-94.6); and NPV, 91.3% (95% CI: 82.8-96.4).

Discussion

In our study, regardless of the smear microscopy results, the AMTD test results showed sensitivity and specificity comparable to those in the literature. A systematic review of 125 studies not exclusively of patients with paucibacillary disease estimated a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 96.8% for commercial nucleic-acid amplification tests.( 15 ) A study not exclusively of patients with paucibacillary disease that compared the AMTD test with GeneXpert found a sensitivity of 96.8% and a specificity of 91.2% for the AMTD test. ( 16 ) It is possible that the difference observed relative to the values estimated in our study is due to the sample composition: whereas the eligibility criteria of the aforementioned study were too restrictive, our patients were selected only because they were seropositive for HIV.

The observed discrepant results, i.e., results that were positive by the AMTD test and negative by culture, may be due to laboratory contamination or to characteristics of the method used. The AMTD test can detect non-viable or dead bacilli, which are hardly to grow in culture. The opposite, i.e., results that were negative by the AMTD test and positive by culture, may indicate the presence of inhibitory substances, which were not examined in the present study.

A feature of nucleic-acid amplification tests is that sensitivity is compromised at the expense of specificity.( 15 ) Other factors that contribute to decreased sensitivity are poor, paucibacillary, or negative samples (in HIV-infected patients) and the presence of inhibitory substances.

The present study showed that, in tuberculosis/HIV-infected patients, the AMTD test was able to detect M. tuberculosis complex in a greater number of samples than culture. However, culture is not 100% sensitive and can yield false-negative results, such as when samples contain dead bacilli, non-viable bacilli (because of decontamination of samples), or less than the minimum detectable amount for culture (approximately 102 bacilli/mL). Therefore, the study results may have been influenced by the chosen reference test.

Although it was not the purpose of our study, analysis of the results of direct examination showed that only one smear microscopy-positive sample was not detected by the AMTD test, possibly because of inhibitors, given that M. tuberculosis was isolated by the two culture methods. Smear microscopy did not detect AFB in approximately 21% of the samples in which the AMTD test was positive. This shows the weakness of smear microscopy in detecting mycobacteria in patients who are seropositive for HIV. Several factors, such as the expertise of the technician; the quality of the sample, which needs to contain between 5,000 and 10,000 bacilli/mL in order to prevent false-negative results( 17 , 18 ); and particular conditions, such as HIV co-infection,( 18 - 20 ) directly influence smear microscopy results. However, smear microscopy remains an important tool for resource-poor countries, since it is the most rapid and inexpensive method available in all countries.

Studies have reported that the sensitivity of the AMTD test varies depending of the prevalence of HIV. However, they have shown the effectiveness of the method in identifying strains in smear microscopy-negative samples.( 21 - 23 )

The AMTD test is approved for use in respiratory samples regardless of smear microscopy results. It provides the greatest benefit to patients when used in smear microscopy-negative samples, given that it enables early diagnosis and the initiation of specific treatment. In our study, according to the reference method used, we obtained sensitivity and specificity similar to that reported by other studies not exclusively of HIV-infected patients.( 24 - 28 )

The main advantage of the routine use of nucleic-acid amplification tests in laboratories is the speed at which results are obtained, enabling early intervention when necessary. However, these tests should not replace culture, since they are able to detect non-viable microorganisms. For the same reason, they are also not useful for monitoring treatment, given that they provide non-quantitative results, which should be interpreted together with results of the conventional tests and with clinical data. However, they are useful in distinguishing between M. tuberculosis and MOTT, becoming an important tool in patients with heavy MOTT colonization/MOTT disease, as is the case of HIV-infected patients.

In conclusion, the AMTD test showed good sensitivity and specificity in the population studied, enabling the laboratory detection of M. tuberculosis complex in paucibacillary respiratory specimens.

Footnotes

Study carried out at the Evandro Chagas Clinical Research Institute and at the National Institute of Quality Control in Health, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Financial support: None

Contributor Information

Leonardo Bruno Paz Ferreira Barreto, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Maria Cristina da Silva Lourenço, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Valéria Cavalcanti Rolla, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Valdiléia Gonçalves Veloso, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Gisele Huf, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis control report 2010. Geneva: World Heath Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Tuberculosis. Fact sheet No 104. Geneva: World Heath Organization; 2013. [[cited 2013 Jul 9]]. a Available from:. Available from:. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whalen CC, Nsubuga P, Okwera A, Johnson JL, Hom DL, Michael NL, et al. Impact of pulmonary tuberculosis on survival of HIV-infected adults: a prospective epidemiologic study in Uganda. AIDS. 2000;14(9):1219–1228. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whalen C, Horsburgh CR, Jr, Hom D, Lahart C, Simberkoff M, Ellner J. Site of disease and opportunistic infection predict survival in HIV-associated tuberculosis. AIDS. 1997;11(4):455–460. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whalen C, Horsburgh CR, Hom D, Lahart C, Simberkoff M, Ellner J. Accelerated course of human immunodeficiency virus infection after tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(1):129–135. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whalen C, Okwera A, Johnson J, Vjecha M, Hom D, Wallis R, et al. Predictors of survival in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. The Makerere University-Case Western Reserve University Research Collaboration. Pt 1Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(6):1977–1981. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conde MB, Melo FA, Marques AM, Cardoso NC, Pinheiro VG, Dalcin Pde T et al III Brazilian Thoracic Association Guidelines on tuberculosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(10):1018–1048. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009001000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyendak MR, Lewinsohn DA, Lewinsohn DM. New diagnostic methods for tuberculosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22(2):174–182. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283262fe9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Updated guidelines for the use of nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(1):7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent PT, Kubica GP. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory. Atlanta: US Dept. of Health and Human Services; Public Health Service; Centers for Disease Control; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson Beckton. BACTECTM MGITTM 960 User's manual. Franklin Lakes: Beckton Dickinson; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gen-Probe Inc . Teste amplified para a detecção directa das micobactérias do complexo Mycobacterium tuberculosis. San Diego: Gen-Probe Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Clin Chem. 2003;49(1):7–18. doi: 10.1373/49.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barreto LB, Lourenço MC, Rolla VC, Veloso VG, Huf G. Evaluation of the Amplified MTD(r) Test in respiratory specimens of human immunodeficiency virus patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(10):1420–1420. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ling DI, Flores LL, Riley LW, Pai M. Commercial nucleic-acid amplification tests for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in respiratory specimens: meta-analysis and meta-regression. PLoS One. 2008;3(2): doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teo J, Jureen R, Chiang D, Chan D, Lin R. Comparison of two nucleic acid amplification assays, the Xpert MTB/RIF and the amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct assay, for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in respiratory and nonrespiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(10):3659–3662. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00211-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreira AA, Queiroz KC, Torres KP, Ferreira MA, Accioly H, Alves MS. Os fatores associados à tuberculose pulmonar e a baciloscopia: uma contribuição ao diagnóstico nos serviços de saúde pública. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2005;8(2):142–149. doi: 10.1590/S1415-790X2005000200006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica . Manual nacional de vigilância laboratorial da tuberculose e outras micobactérias. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Rie A, Page-Shipp L, Scott L, Sanne I, Stevens W. Xpert((r)) MTB/RIF for point-of-care diagnosis of TB in high-HIV burden, resource-limited countries: hype or hope? Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10(7):937–946. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministério da Saúde. Fundação Nacional de Saúde. Centro Nacional de Pneumologia Sanitária . Manual de recomendações para o controle da tuberculose no Brasil. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boehme CC, Nabeta P, Hillemann D, Nicol MP, Shenai S, Krapp F, et al. Rapid molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin resistance. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(11):1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kambashi B, Mbulo G, McNerney R, Tembwe R, Kambashi A, Tihon V, et al. Utility of nucleic acid amplification techniques for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5(4):364–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kivihya-Ndugga L, Van Cleeff M, Juma E, Kimwomi J, Githui W, Oskam L, et al. Comparison of PCR with the routine procedure for diagnosis of tuberculosis in a population with high prevalences of tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(3):1012–1015. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1012-1015.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palomino JC. Molecular detection, identification and drug resistance detection in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;56(2):103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemaître N, Armand S, Vachée A, Capilliez O, Dumoulin C, Courcol RJ. Comparison of the real-time PCR method and the Gen-Probe amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in pulmonary and nonpulmonary specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(9):4307–4309. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4307-4309.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coll P, Garrigó M, Moreno C, Marti N. Routine use of Gen-Probe Amplified Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Direct (MTD) test for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with smear-positive and smear-negative specimens. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7(9):886–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Sullivan CE, Miller DR, Schneider PS, Roberts GD. Evaluation of Gen-Probe amplified mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test by using respiratory and nonrespiratory specimens in a tertiary care center laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(5):1723–1727. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1723-1727.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamboa F, Fernandez G, Padilla E, Manterola JM, Lonca J, Cardona PJ, et al. Comparative evaluation of initial and new versions of the Gen-Probe Amplified Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Direct Test for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in respiratory and nonrespiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(3):684–689. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.684-689.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]