Summary

Nestin-positive (Nes+) cells are important hematopoiesis-supporting constituents in adult bone marrow. However, how these cells originate during endochondral bone development is unknown. Studies using mice expressing GFP under the direction of nestin promoter/enhancer (Nes-GFP) revealed distinct endothelial and non-endothelial Nes+ cells in the embryonic perichondrium; the latter were early cells of the osteoblast lineage immediately descended from their progenitors upon Indian hedgehog action and Runx2 expression. During vascular invasion and formation of ossification centers, these Nes+ cells were closely associated with each other and increased in number progressively. Interestingly, cells targeted by tamoxifen-inducible cre recombinase driven by nestin enhancer (Nes-creER) in developing bone marrow were predominantly endothelial cells. Furthermore, Nes+ cells in postnatal bones were heterogeneous populations including a range of cells in the osteoblast and endothelial lineage. These findings reveal an emerging complexity of stromal populations, accommodating Nes+ cells as vasculature-associated early cells in the osteoblast and endothelial lineage.

Introduction

Bone is a multifunctional organ providing protection of vital organs, levers for motion and withstanding gravity, and the sole site in which hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) normally generate blood cells in adult mammals. Most bones are formed through endochondral ossification, in which a cartilage template is replaced by bone and bone marrow. During this process, mesenchymal condensations first define the domain for the future bones, and then develop into cartilage that continues to grow as chondrocytes proliferate (Kronenberg, 2003). When cells in the central region stop proliferating and become hypertrophic, osteoblasts appear in the surrounding perichondrium (Maes et al., 2010). A population of osteoblast precursors and endothelial cells in the perichondrium co-invades the avascular cartilage and establishes the primary ossification center; osteoblasts and stromal cells then populate the highly vascularized bone marrow. The principal site of hematopoiesis moves from the fetal liver to the spleen and bone marrow during late embryonic development (Christensen et al., 2004). Endochondral ossification establishes an HSC niche de novo within bone marrow (Chan et al., 2009). Marrow stromal cells begin making chemokines, such as chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (CXCL12) to support bone marrow hematopoiesis (Nagasawa et al., 1996). A wide range of cells of endochondral bones including endosteal osteoblasts (Calvi et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003), endothelial cells, pericytes (Ding et al., 2012; Sacchetti et al., 2007), and perivascular stromal cells, including CXCL12-abundant reticular cells (Sugiyama et al., 2006), provides microenvironmental cues that maintain hematopoietic stem cells in bone marrow. In adult bone, cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) in response to a nestin promoter/enhancer (Nes-GFP) and those expressing Nes-creER exhibit mesenchymal stem/progenitor activities and constitute an essential HSC niche component (Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2010). Nestin is an intermediate filament protein originally described in neural stem cells, and is also expressed in various cell types including pericytes and nascent endothelial cells in the developing limb bud and growing tumors (Mokry et al., 2004; Teranishi et al., 2007; Wroblewski et al., 1997). However, whether similar nestin-expressing cells participate in the process of fetal endochondral ossification and in the formation of cells that support hematopoiesis is unknown. In this study, we sought to identify the origin, heterogeneity and fate of cells expressing nestin during endochondral bone development. Our data reveal that nestin-expressing cells are associated with vasculature and encompass early cells in the osteoblast, stromal and endothelial lineages and place nestin expression downstream of Indian hedgehog and Runx2 action in the mesenchymal lineages.

Results

Development of endothelial and non-endothelial nestin+ cells during endochondral ossification

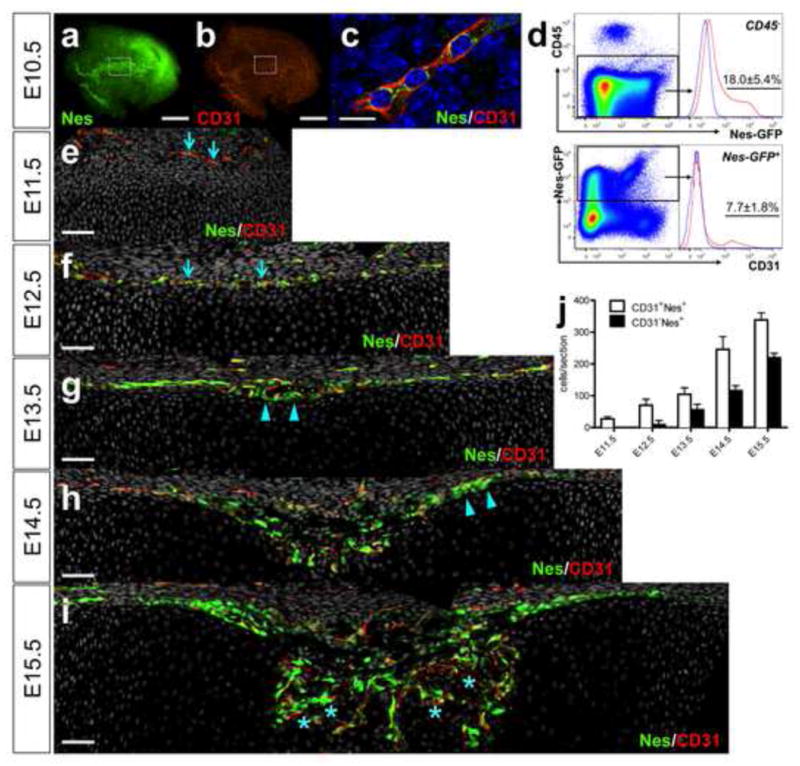

We studied embryonic endochondral bones using Nes-GFP mice (Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2010; Mignone et al., 2004). At embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5), Nes+ cells were distributed within the limb bud, partly in a reticular pattern that resembled that of CD31+ cells, though cells toward the distal end of the limb bud did not show this pattern (Fig. 1a, b). The reticular Nes+ cells co-expressed CD31 (Fig. 1c). Analysis of dissociated limb bud cells revealed that 18.0±5.4% of CD45− cells were Nes+, and 7.7±1.8% of Nes+ cells were CD31+ (Fig. 1d). At E11.5, Nes+ cells were seldom found within mesenchymal condensations, and a small number of CD31+Nes+ cells were in the area surrounding condensations (Fig. 1e, arrows). When the growth cartilage appeared at E12.5, Nes+ cells were found in the perichondrium with large numbers expressing CD31+ (Fig. 1f and Fig. S1a, arrows). At E13.5, a distinct group of CD31− Nes+ cells appeared in the innermost portions of the perichondrium adjacent to the incipient hypertrophic chondrocytes and vasculature (Fig. 1g and Fig. S1b, arrowheads). At E14.5, both types of Nes+ cells dominated the inner aspect of the enlarging wedge-shaped perichondrium, and CD31− Nes+ cells were aligned on the innermost portion of the flanking perichondrium (Fig. 1h, arrowheads). At E15.5, as vascular invasion into the cartilage template occurred, the nascent primary ossification center was populated by both CD31+ and CD31− Nes+ cells that were closely associated with each other (Fig. 1i, asterisks, see also Fig. S1c). The majority of CD31+ cells found within the perichondrium and the primary ossification center was also Nes+. CD31+Nes− cells were found mostly outside the bone anlage. The quantification on confocal sections revealed that CD31+Nes+ cells appeared earlier than CD31− Nes+ cells, and both fractions continued to increase as endochondral ossification advanced (Fig. 1j). Therefore, these data suggest that distinct endothelial and non-endothelial populations of Nes+ cells are found in the embryonic perichondrium, and that these cells closely interact with each other and increase in number during vascular invasion and endochondral ossification.

Figure 1. Development of endothelial and non-endothelial nestin+ cells during endochondral ossification.

a–c. E10.5 proximal limb bud of Nes-GFP mice stained whole-mount for CD31 and nuclei. x40 (a, b), x630 confocal (c), green: EGFP, red: Alexa546, blue: DAPI. Scale bars: 400μm (a, b), 10 μm (c). Note GFP is cytoplasmic, and CD31 is membraneous. d. Flow cytometry analysis of E10.5 Nes-GFP limb bud cells stained for CD45 and CD31 (n=3, data represented as mean ± S.D.). Upper panel: nucleated singlets gated for CD45−, blue line: GFP− control limb bud cells, lower panel: CD45− fraction gated for Nes-GFP+, blue line: GFP+ cells, unstained control. e–i. E11.5–15.5 femur sections of Nes-GFP mice stained for CD31 and nuclei. x200 confocal (e–i), green: EGFP, red: Alexa546, gray: DAPI. Dorsal halves of growth cartilage are shown. Perichondrium is on top. Arrows: CD31+Nes+ cells (e, f), arrowheads: CD31− Nes+ cells in perichondrium (g, h). Asterisks in vascular invasion front: intimate association of CD31+Nes+ and CD31− Nes+ cells (i). Scale bars: 50μm. j. Quantification of CD31+Nes+ cells (white bars) and CD31− Nes+ cells (black bars) in perichondrium and primary ossification center (n=3–6).

Non-endothelial nestin+ cells encompass early cells of the osteoblast lineage

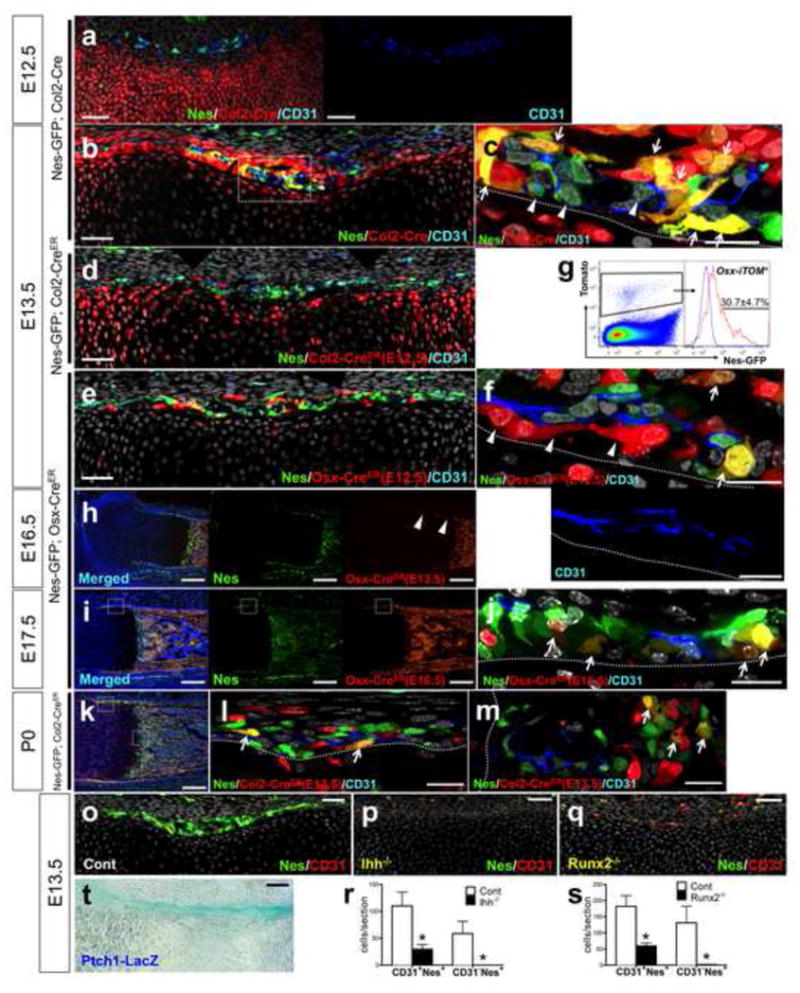

Chondrocytes and chondro-perichondrial progenitors of embryonic endochondral bones express type II collagen (Col2) (Maes et al., 2010; Nakamura et al., 2006; Szabova et al., 2009). To understand how these embryonic progenitors contribute to Nes+ populations, we tracked cell fates using triple-transgenic mice carrying Nes-GFP, constitutively active Col2-cre (Ovchinnikov et al., 2000) and a Rosa26 tomato reporter (Madisen et al., 2010). In this system, cells expressing Col2 and their descendants become red, and if they express Nes-GFP concurrently, they become yellow. At E12.5, red cells appeared mostly within the growth cartilage and some in the perichondrium, and were completely separate from CD31+Nes+ cells (Fig. 2a). At E13.5, almost all the CD31− Nes+ cells in the perichondrium were yellow (Fig. 2b, c, arrows), indicating that they were either expressing Col2 or were descendants of Col2+ cells. In contrast, CD31+Nes+ cells remained green (Fig. 2c, arrowheads). To further test if these Nes+ cells themselves express Col2 or descended from Col2-expressing cells, triple-transgenic mice carrying Nes-GFP, inducible Col2-creER (Nakamura et al., 2006) and a Rosa26 tomato reporter were generated. These mice received tamoxifen injection at E12.5 and were observed 24 hours later at E13.5. In this paradigm, cells actively expressing Col2 undergo recombination in the presence of tamoxifen and become red. Col2+ cells were seen mostly within the growth cartilage and some in the perichondrium, and were completely separate from Nes+ cells (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, when mice received tamoxifen at E13.5 and were analyzed seven days later at P0, descendants of Col2+ cells at E13.5 became yellow in the perichondrium and primary spongiosa (Fig. 2k–m). Therefore, these data suggest that the yellow cells in the perichondrium in Figure 2b are descended from cells such as the red cells in Figure 2d.

Figure 2. Non-endothelial nestin+ cells encompass early cells of the osteoblast lineage.

a–c. Nes- GFP; Col2-cre; R26RTomato femur sections stained for CD31 and nuclei. E12.5, x200 confocal (a) (right panel: CD31 single-color) and E13.5, x200 (b), x630 confocal of dotted area (c). Arrows: CD31− Nes+ Tomato+ cells, allowheads: CD31+Nes+Tomato− cells. d. Nes-GFP; Col2-creER; R26RTomato E13.5 femur sections stained for CD31 and nuclei. Pregnant mice received 2mg tamoxifen at E12.5. x200 confocal. e, f. Nes-GFP; Osx-creER; R26RTomato E13.5 femur sections stained for CD31 and nuclei. Pregnant mice received 2mg tamoxifen at E12.5. x200 (e), x630 confocal of the osteogenic perichondrium (f) (lower panel: CD31 single-color). Arrows: CD31− Nes+ Tomato+ cells, arrowheads: perivascular Tomato+ cells. Green: EGFP, red: tdTomato, blue: Alexa633, gray: DAPI. Scale bars: 50μm (a, b, d, e), 20μm (c, f). g. Flow cytometry analysis of E13.5 Nes-GFP; Osx-creER; R26RTomato limb cells (tamoxifen at E12.5) stained for CD45. CD45− fraction gated for Tomato+, blue line: Nes-GFP− Tomato+ limb cells (n=3, data represented as mean ± S.D.). h. Nes- GFP; Osx-creER; R26RTomato E16.5 femur sections (tamoxifen at E13.5) stained for nuclei. Arrowheads: Tomato+ cells disappearing from the osteogenic perichondrium. x100. Green: EGFP, red: tdTomato, blue: DAPI. i, j. Nes- GFP; Osx-creER; R26RTomato E17.5 femur sections (tamoxifen at E16.5) stained for CD31 and nuclei. x100 (i), x630 confocal of dotted area (j). Arrows: CD31− Nes+Tomato+ cells on the innermost layer of the osteogenic perichondrium. Scale bars: 200μm (h, i), 50μm (j). k–m. Nes-GFP; Col2-creER; R26RTomatoP0 femur sections (tamoxifen at E13.5) stained for CD31 and nuclei. x100 (k), x630 confocal of dotted area (l: perichondrium, m: primary spongiosa). Arrows: CD31− Nes+ Tomato+ cells. Green: EGFP, red: tdTomato, blue: Alexa633, gray: DAPI. Scale bars: 200μm (k), 20μm (l, m). o–q. E13.5 femur sections stained for CD31 and nuclei. Control (o), Ihh−/ − (p) and Runx2−/ − (q), x200 confocal. Green: EGFP, red: Alexa546, gray: DAPI. Scale bars: 50μm. r. Quantification of CD31+Nes+ cells and CD31− Nes+ cells in perichondrium. Control (while bars) and Ihh−/ − (black bars), n=4 per group, *p<0.05. s. Quantification of CD31+Nes+ cells and CD31− Nes+ cells in perichondrium. Control (while bars) and Runx2−/ − (black bars), n=4 per group, *p<0.05. t. Ptch1LacZ/+ femur stained for β-galactosidase activity. E13.5, x200. Scale bar: 50μm.

Cells expressing osterix (Osx) in the embryonic perichondrium are osteoblast precursors capable of differentiating into osteoblasts, osteocytes and peritrabecular stromal cells (Maes et al., 2010). To understand how Nes+ cells are related to osterix-expressing precursors, triple transgenic mice carrying Nes-GFP, inducible Osx-creER and Rosa26 tomato reporter received tamoxifen at E12.5 and were analyzed 24 hours later at E13.5. At E13.5, a great majority of red cells was found in the perichondrium (Fig. 2e), and some of these cells overlapped with CD31− Nes+ cells and became yellow in the perichondrium (Fig. 2f, arrows). In addition, these red cells were closely associated with, but clearly independent from CD31+Nes+ cells (Fig. 2f, arrowheads). Analysis of dissociated limb cells revealed that 30.7±4.7% of red cells expressed Nes-GFP (Fig. 2g). Furthermore, when mice received tamoxifen at E13.5 and were analyzed at E16.5, a large majority of descendants of osterix-expressing cells at E13.5 moved into the primary ossification center, and did not stay in the newly generated part of the perichondrium (Fig. 2h, arrowheads). These red cells completely disappeared from the perichondrium when chased until postnatal day 0 (data not shown). When mice received tamoxifen at E16.5 and were observed 24 hours later at E17.5, the domain of red cells extended over the Nes+ perichondrium (Fig. 2i). In fact, many yellow cells were observed on the inner aspect of the perichondrium (Fig. 2j, arrows), indicating that these CD31− Nes+ perichondrial cells expressed osterix. Thus, at least some CD31− Nes+ cells in the perichondrium are Osx+ osteoblast precursors that are continually replenished from their precursors as bones become longer.

Runx2 is an essential regulator of osteoblast differentiation downstream of Indian hedgehog (Ihh), as Runx2 mRNA is absent from the perichondrium in the absence of Ihh (St-Jacques et al., 1999). The Ihh receptor, Patched1, is a direct Ihh target gene. In Ptch1-LacZ knock-in mice, robust β-galatosidase activities were observed in the perichondrium at E11.5 (data not shown) and E13.5 (Fig. 2t), demonstrating Ihh action in the perichondrium. To determine the role of Ihh signaling in Nes-GFP cells, double-transgenic mice carrying Nes-GFP and Ihh-null alleles were analyzed at E13.5. The number of CD31+Nes+ cells was significantly reduced and CD31− Nes+ cells were completely abrogated in the resultant thin perichondrium (Fig. 2p, r). Runx2-deficiency also significantly reduced the number of CD31+Nes+ cells, and led to complete loss of CD31− Nes+ cells in the perichondrium at E13.5 (Fig. 2q, s). No CD31− Nes+ cells were observed in Runx2-deficient perichondrium when bones developed further at E16.5 and E18.5 (data not shown). Thus, Ihh and Runx2 are required for generating non-endothelial Nes+ cells in the perichondrium during embryonic endochondral bone development. In addition, Ihh and Runx2 are also important for endothelial Nes+ cells in the perichondrium, and disappearance of CD31− Nes+ cells in Ihh-null or Runx2-null embryos is likely to occur through a combination of cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous effects.

These data indicate that Ihh and Runx2 both are needed to direct mesenchymal precursors to become Nes+ cells of the osteoblast lineage in the perichondrium; some of these cells become Osx+ pre-osteoblasts.

Nes-creER preferentially targets nestin+ endothelial cells in developing bone marrow

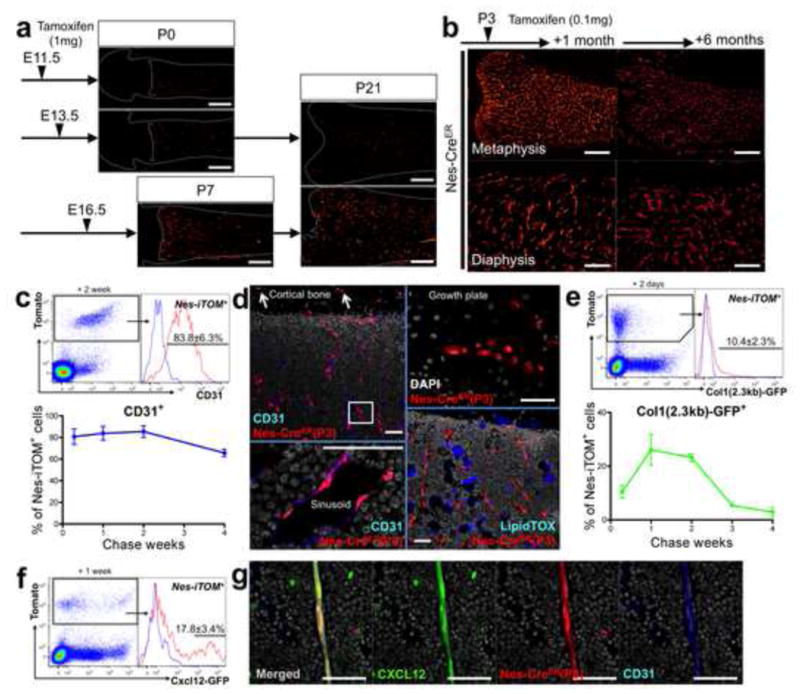

In order to unravel the fate of Nes+ cells at different stages of endochondral ossification, we took advantage of mice expressing an inducible Cre recombinase under the control of a minimal promoter and a 1.8kb nestin 2nd intron enhancer (Nes-creER) (Balordi and Fishell, 2007), along with a Rosa26 tomato reporter. When mice received tamoxifen before the primary ossification center was formed, either during formation of condensations at E11.5 or of the osteogenic perichondrium at E13.5, only a small number of red cells was observed in bone upon chase until the day of birth (P0) or until postnatal day 21 (P21). When mice received tamoxifen at E16.5 at the time that the marrow space starts to form, larger numbers of red cells appeared in bone, when chased until P7 or P21 (Fig. 3a). Therefore, there appears to be a transition of Nes-creER expression before and after the primary ossification center is established. To delineate the fate of Nes-creER-targeted cells after bone marrow hematopoiesis is fully established, mice received tamoxifen at postnatal day 3 (P3). Descendants of these cells (Nes-creER(P3)) continued to dominate the entire bone marrow up to the border with the growth plate, in a reticular pattern similar to marrow vasculature at least for 6 months thereafter (Fig. 3b). Analysis of dissociated cells from the epiphysis and metaphysis revealed that a majority of Nes-creER(P3) cells were consistently positive for CD31 for the entire first month of chase (Fig. 3c). Histological analysis revealed that Nes-creER(P3) red cells were predominantly sinusoidal endothelial cells in bone marrow (Fig. 3d, left panels). In contrast, Nes-creER(P3) cells became only a small number of red osteoblasts and osteocytes in the cortical bone (Fig. 3d arrows, see also Fig. S2a), and very infrequently, chondrocytes in the growth plate (Fig. 3d, right upper panel), but not adipocytes (Fig. 3d, right lower panel). To understand the contribution of Nes-creER(P3) cells to osteoblastic cells, triple transgenic mice carrying Col1(2.3kb)-GFP, Nes-creER and a Rosa26 tomato reporter were generated and received tamoxifen at P3. Analysis of dissociated bone cells revealed that 10.4±2.3% of Nes-creER(P3) cells were osteoblasts expressing GFP at 48 hours after injection; this increased to 26.1±5.7% and 23.2±1.5% for the first and second weeks, and then decreased to 5.4±0.1% and 2.9±1.7% for the third and fourth weeks, respectively (Fig. 3e, see also Fig. S2b for images).

Figure 3. Nes-creER preferentially targets nestin+ endothelial cells in developing bone marrow.

a. Pregnant mice received 2mg tamoxifen at indicated points (E11.5, 13,5 or 16.5), and Nes-creER; R26RTomato mice were chased until indicated postnatal days (P0, P7 or P21). Distal femur sections, x40. Red: tdTomato. Scale bars: 500μm. b. Nes-creER; R26RTomato mice received 0.1mg tamoxifen at P3 and were chased for 1 month (left panels) and 6 months (right panels). Upper panels: distal femur, metaphysis, x40, scale bars: 500μm, lower panels: diaphysis, x100, scale bars: 200μm. Red: tdTomato. c. Flow cytometry analysis of epiphyseal/metaphyseal cells from Nes-creER; R26RTomato mice received tamoxifen at P3 and chased for indicated periods. Cells were stained for CD45 and CD31. Upper panel: CD45− fraction after 2 weeks of chase gated for Tomato+, blue line: Tomato+ cells, unstained control. Lower panel: Mice were chased for 2 days (n=4), 1 week (n=6), 2 weeks (n=2) and 4 weeks (n=4). The percentage of CD31+ cells within CD45− Tomato+ fraction is shown. d. Nes-creER; R26RTomato (tamoxifen at P3) femur sections. Left panels: diaphysis after 1 month of chase stained for CD31 and nuclei. Upper left: x200 confocal, arrows: Tomato+ osteocytes in cortical bone; Lower left:, x630 confocal of boxed area from upper left, rotated perpendicularly, bone marrow sinusoid. Red: tdTomato, blue: Alexa633, gray: DAPI. Upper right: growth plate cartilage after 2 months of chase. Note Tomato+ columnar chondrocytes. x400 confocal, Red: tdTomato, gray: DAPI. Lower right panel: diaphysis after 4 months of chase stained for lipid. x200 confocal, Red: tdTomato, blue: LipidTOX Deep Red. Scale bars: 50μm. e. Flow cytometry analysis of epiphyseal/metaphyseal cells from Col1(2.3 kb)-GFP; Nes-creER; R26RTomato mice received tamoxifen at P3 and chased for indicated periods. Cells were stained for CD45. Upper panel: CD45− fraction after 2 days of chase gated for Tomato+, blue line: Tomato+ cells, unstained control. Lower panel: Mice were chased for 2 days (n=4), 1 week (n=5), 2 weeks (n=2), 3 weeks (n=4) and 4 weeks (n=4). The percentage of Col1(2.3 kb)-GFP+ cells within CD45− Tomato+ fraction is shown. f, g. Cxcl12-GFP; Nes-creER; R26RTomato mice received tamoxifen at P3 and chased for 1 week. Flow cytometry analysis of epiphyseal/metaphyseal cells (f); CD45− fraction gated for Tomato+ (n=6, blue line: Cxcl12-GFP− Tomato+ cells), sections of femur diaphysis bone marrow stained for CD31 and nuclei (g), x630 confocal. Green: EGFP, red: tdTomato, blue: Alexa633, gray: DAPI. Scale bars: 50μm. All data represented as mean ± S.D.

Various types of cells in bone and bone marrow express CXCL12, a crucial chemokine for maintaining hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Nagasawa et al., 1996), whereas depletion of Nes-creER cells rapidly reduces HSCs (Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2010). To understand how Nes-creER cells contribute to CXCL12-expressing cells, triple-transgenic mice carrying Cxcl12-GFP (Ara et al., 2003), Nes-creER and a Rosa26 tomato reporter were generated and received tamoxifen at P3. After a week of chase, 17.8±3.4% of Nes-creER(P3) cells were Cxcl12-GFP+ (Fig. 3f), and Nes-creER(P3) endothelial cells of the arterioles were found to be Cxcl12-GFP+; some of the Nes-creER cells were stromal cells as well (Fig. 3g, see also Fig. S2c and Fig. S2d for images). These data suggest that Nes-creER predominantly marks cells that become endothelial cells, as well as cells that become osteoblasts, osteocytes, stromal cells, and chondrocytes.

Nestin+ cells in developing postnatal bones are heterogeneous stromal cell populations

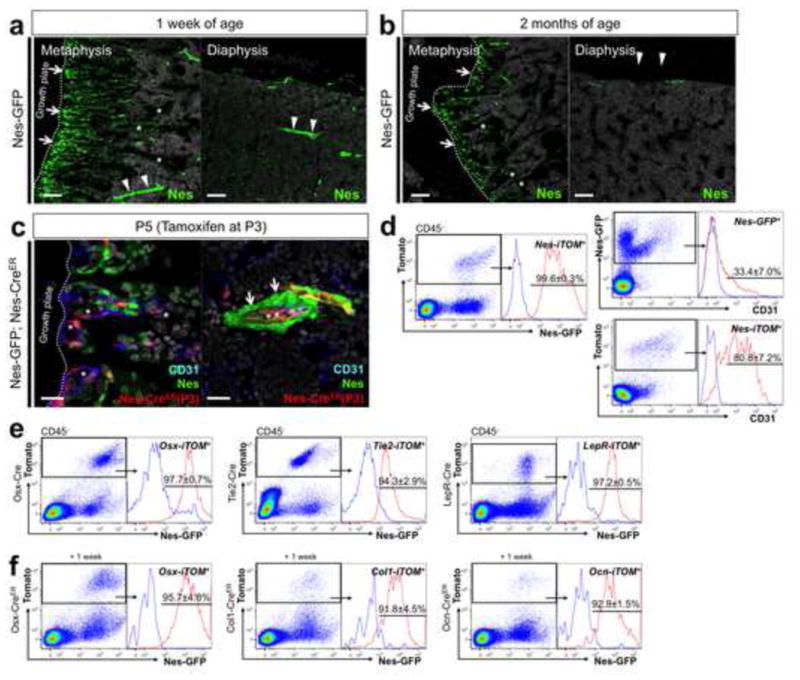

In postnatal endochondral bones at one week of age, the Nes-GFP signal was particularly intense in two locations: perivascular cells in the primary spongiosa immediately adjacent to the growth plate (Fig. 4a, left panel, arrows) and pericytes of the arterioles (Fig. 4a, arrowheads and see Fig. 4c below). In addition, moderate Nes-GFP signal was found in osteoblasts on the bone surface, osteocytes (Fig. 4a, asterisks, see also Fig. S3) and endothelial cells (Fig. 4c, asterisks). In adult endochondral bones at two months of age, the number of Nes-GFPhigh cells was decreased in the primary spongiosa and bone marrow (Fig. 4b, left panel, arrows). Nes-GFPlow cells in osteoblasts on bone surfaces and osteocytes were also decreased but still observed (Fig. 4b, left panel, asterisks, right panel, arrowheads, see also Fig. S3). To delineate the difference between cell types that Nes-GFP and Nes-creER differentially target, mice carrying both of these transgenes were generated, received tamoxifen at P3 and analyzed 48 hours later. A large majority of red cells targeted by Nes-creER was found to be CD31+ endothelial cells in the primary spongiosa and bone marrow (Fig. 4c, asterisks). Analysis of dissociated bone cells revealed that almost all the Nes-creER-tomato cells were also Nes-GFP positive (Fig. 4d, left panel). However, while 33.7±7.0% of Nes-GFP cells were CD31+, 80.8±7.2% of Nes-creER-tomato cells were CD31+ (Fig. 4d, right panels), suggesting that Nes-creER preferentially targets an endothelial subpopulation of Nes+ cells. To study if cells expressing Nes-GFP and/or Nes-creER-tomato actually express nestin gene, we examined Nestin immunoreactivity and the expression of Nestin mRNA in these cell populations (Fig. S3e–k). These data confirmed that cells expressing these transgenes also express nestin mRNA and protein. To delve more into the heterogeneity of Nes+ cells in postnatal bones, Nes-GFP was combined with cre lines targeting distinct stromal cell lineages; Osx-cre for osteoblasts (Rodda and McMahon, 2006), Tie2-cre for endothelial cells and LepR-cre for perivascular stromal cells (Ding et al., 2012). 97.7±0.7% of Osx-cre, 94.3±2.9% of Tie2-cre and 97.2±0.5% of LepR-cre targeted CD45− cells at P3 (Tie2-cre) or P7 (Osx-cre, LepR-cre) were positive for Nes-GFP (Fig. 4e). To focus further on osteoblast subpopulations of Nes+ cells, Nes-GFP was combined with creERT2 lines targeting different stages of the osteoblast lineage (Osx-creER, Col1(3.2kb)-creER and osteocalcin (Ocn)-creER). After a week of chase after pulsed at P3, 95.7±4.8%, 91.8±4.5% and 92.9±1.5% of cells targeted by Osx-creER, Col1(3.2kb)-creER and Ocn-creER were positive for Nes-GFP, respectively (Fig. 4f). Therefore, inasmuch as these reporter lines are specific for their respective lineages, Nes+ cells include a wide range of cells in the endothelial, stromal and osteoblast lineage.

Figure 4. Nestin+ cells in developing postnatal bones are heterogeneous stromal cell populations.

a, b. Distal femur sections of Nes-GFP mice at 1 week of age (a) and 2 months of age (b) stained for nuclei. x100 confocal, metaphysis (left panels) and diaphysis (right panels). Arrows: Nes-GFPhigh cells in the primary spongiosa adjacent to the growth plate, arrowheads in (a): pericytes of bone marrow arterioles, asterisks: osteoblasts on bone surface and osteocytes, arrowheads in (b): osteocytes in cortical bone. Scale bars: 100μm. c, d. Nes- GFP; Nes-creER; R26RTomato mice received tamoxifen at P3 and chased for 48 hours. (c) Femur sections of metaphysis (left panel) and diaphysis bone marrow (right panel) stained for CD31 and nuclei. Asterisks: CD31+Tomato+ cells, arrows: pericytes of bone marrow arterioles, x630 confocal, green: EGFP, red: tdTomato, blue: Alexa633, gray: DAPI. Scale bars: 20μm. (d) Flow cytometry analysis of epiphyseal/metaphyseal cells stained for CD45 and CD31; CD45− fraction gated for Tomato+ (left panel and lower right panel), Nes-GFP+ (upper right panel) (n=4), blue line: Nes-GFP− Tomato+ cells (left panel) and unstained controls (right panels). e. Flow cytometry analysis of epiphyseal/metaphyseal cells from Nes-GFP; R26RTomato mice that also carry Osx-cre (left panel), Tie2-cre (center panel) or LepR-cre (right panel). Cells were harvested at P3 (Tie2-cre) or P7 (Osx-cre, LepR-cre). f. Flow cytometry analysis of epiphyseal/metaphyseal cells from Nes-GFP; R26RTomato mice that also carry Osx-creER (left panel), Col1-creER (center panel) or Ocn-creER (right panel). Tamoxifen was administered at P3 and cells were harvested a week later. CD45− fraction gated for Tomato+ (Osx-cre: n=3, Tie2-cre: n=4, LepR-cre: n=3, Osx-creER: n=6, Col1-creER: n=4, Ocn-creER: n=3), blue lines: GFP− control. All data represented as mean ± S.D.

Discussion

Establishment of hematopoiesis and bone formation within the bone marrow during embryonic endochondral ossification requires an orchestrated invasion of osteoblast precursors and endothelial cells from the perichondrium into the avascular cartilage. Many cell types putatively supporting hematopoietic stem cells in bone marrow, e.g. osteoblasts, stromal cells, pericytes and endothelial cells, are generated simultaneously as the primary ossification center forms. Our data indicate that nestin+ cells during this process are associated with vasculature and include both endothelial and non-endothelial cells. We used two different “nestin” constructs both containing an intronic enhancer sequence; one uses a nestin gene promoter to drive GFP expression (Mignone et al., 2004), while the other uses a minimal promoter to drive creER expression (Balordi and Fishell, 2007). We found that the two constructs mark both endothelial and mesenchymal cell types, with the latter marking a higher proportion of endothelial cells in fetal and early postnatal life.

Mendez-Ferrer et al (Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2010) showed that, in adult bone marrow, Nes-GFP+ cells include all cells capable of forming CFU-F colonies in vitro; these colonies form from single cells and can generate osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes in vitro. Also, they showed that Nes-creER targeted cells in adult marrow could become osteoblasts, osteocytes and chondrocytes in vivo and were also required for support of hematopoiesis. We used a series of cell type-specific transgenes and mutant mice to order the expression of the nestin transgenes in fetal bone. We found that neither of these transgenes was expressed in mesenchymal condensations. Nes-GFP was expressed in endothelial and non-endothelial cells in the perichondrium. The latter cells appeared downstream of cells expressing transgenes driven by the type II collagen promoter: Col2-cre-tomato reporter marked chondrocytes and perichondrial cells distinct from cells expressing Nes-GFP+ at E12.5. Similarly, when Col2-creER mice were given tamoxifen at E12.5 and examined at E13.5, the marked cells were distinct from cells expressing Nes-GFP. When similar mice given tamoxifen at E13.5 were examined at P0, many Nes-GFP+ cells were descended from those expressing Col2-creER at E13.5. These findings allow us to place Nes-GFP expression downstream of Col2-creER expression in the lineage of fetal perichondrial cells.

It is of interest that, in fetal life, neither nestin construct marks the mesenchymal condensations that give rise to chondrocytes and osteoblasts; they appear in the perichondrium only after Col2+ cells populate there. Thus, multi-lineage potential is not solely a property of the earliest cells of the osteoblast lineage during development. Further, since osteoblasts and bone lining cells are also Nes+ (Fig. 4a, b and Fig. S3), it is unlikely that all Nes+ cells are multipotent in normal development.

Mice with the Ihh gene ablated fail to form osteoblasts in limb perichondrium (St-Jacques et al., 1999). We found that these mice also fail to generate perichondrial cells expressing Nes-GFP. Mice with the Runx2 gene ablated fail to form osteoblasts (Otto et al., 1997) and these mice fail to generate perichondrial cells expressing Nes-GFP. Thus, perichondrial CD31− Nes-GFP+ cells require both Ihh and Runx2 expression and also appear after expression of the Col2-cre transgene. In contrast, when Osx-creER is activated at E12.5, many CD31− Nes-GFP+ cells at E13.5 expressed the tomato reporter. Similarly, when Osx-creER is activated at later times, expression of the tomato reporter largely overlaps with expression of Nes-GFP. Also, both Col1-creER and Ocn-creER marked a subset of Nes-GFP+ cells. Thus, the CD31− Nes-GFP+ cells appear roughly at the time of Osx expression, and Nes-GFP transgene remains active in subsequent cells of the osteoblast lineage.

Nes-creER directs reporter expression in non-endothelial stromal cells in the marrow and LepR-cre also directs expression in Nes-GFP+ cells; thus, stromal cells represent one fate for nestin-expressing cells. In the accompanying manuscript, Mizoguchi et al (Mizoguchi et al., 2014) show that postnatally marked cells expressing Nes-GFP and Osx-creER-tomato include stromal cells with properties of “mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells”.

Endosteal osteoblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes and perivascular stromal cells have been implicated in defining the hematopoietic stem cell niche in bone marrow (Ding et al., 2012; Ding and Morrison, 2013; Greenbaum et al., 2013). Our data indicate that all these cell types in developing bone marrow express Nes-GFP. We also found that Nes-creER predominantly targets endothelial cells in bone marrow, including Cxcl12+ endothelial cells of the bone marrow arteriole (Fig. 3g). Our findings support the notion that both endothelial and non-endothelial Nes+ cells are important components of the hematopoietic stem cell niche.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Nestin-GFP, Col2a1-cre, Osx-cre, Col2a1-creERT2, Osx-creERT2, Col1-creERT2, Ocn-creERT2, Ihh-Neo/null, Runx2-LacZ/null, Ptch1-LacZ/null, Cxcl12-GFP/null mice have been described elsewhere. Tie2-cre (JAX8863), LepR-cre (JAX8320) and Rosa26-loxP-stop-loxP-tdTomato (R26R-tomato, JAX7914) were acquired from Jackson laboratory. All procedures were conducted in compliance with the Guideline for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals approved by Massachusetts General Hospital’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). For embryonic experiments, male mutant mice were mated to female CD1 mice and the vaginal plug was checked in the morning. Pregnant mice received 1mg tamoxifen (Sigma T5648) and progesterone (Sigma P3972) i.p. For postnatal experiments, 3 days-old mice received 0.1mg of tamoxifen i.p. Tamoxifen was dissolved first in 100% ethanol then in sunflower seed oil (Sigma S5007) overnight at 60C°.

Histology and Flow cytometry

Frozen sections at 15μm thickness were analyzed using a fluorescence (Nikon Eclipse E800) or a confocal (Zeiss LSM510) microscope. Enzymatically digested cells from dissected femurs and tibias were stained for anti-mouse CD45-APC, CD31-eFlour 450 (1:500, eBioscicence), and analyzed using a four-laser BD LSRII flow cytometer. More detailed experimental procedures are available in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Statistical Analysis

Results were represented as mean values ± S.D. Statistical evaluation was conducted based on Mann-Whitney’s U-test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Endothelial and non-endothelial nestin+ cells develop in endochondral ossification

Ihh and Runx2 action are needed for appearance of nestin+ cells becoming osteoblasts

Endothelial cells are preferentially targeted by Nes-creER in developing marrow

Nestin+cel ls in developing bones are a heterogeneous stromal cell population

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andrew McMahon for Ptch1-LacZ and Ihh-null mice and David Rowe for Col2.3-GFP mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DE022564 to N.O., DK056638 and HL069438to P.S.F., and DK056246to H.M.K., Gideon & Sevgi Rodan fellowshipfrom International Bone & Mineral Societyto N.O. and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellowship for Research Abroad and Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists 21689051 to N.O.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Ara T, Tokoyoda K, Sugiyama T, Egawa T, Kawabata K, Nagasawa T. Long-term hematopoietic stem cells require stromal cell-derived factor-1 for colonizing bone marrow during ontogeny. Immunity. 2003;19:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balordi F, Fishell G. Mosaic removal of hedgehog signaling in the adult SVZ reveals that the residual wild-type stem cells have a limited capacity for self-renewal. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14248–14259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4531-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CK, Chen CC, Luppen CA, Kim JB, DeBoer AT, Wei K, Helms JA, Kuo CJ, Kraft DL, Weissman IL. Endochondral ossification is required for haematopoietic stem-cell niche formation. Nature. 2009;457:490–494. doi: 10.1038/nature07547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JL, Wright DE, Wagers AJ, Weissman IL. Circulation and chemotaxis of fetal hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E75. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Morrison SJ. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature. 2013;495:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum A, Hsu YM, Day RB, Schuettpelz LG, Christopher MJ, Borgerding JN, Nagasawa T, Link DC. CXCL12 in early mesenchymal progenitors is required for haematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Nature. 2013;495:227–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423:332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, Lein ES, Zeng H. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes C, Kobayashi T, Selig MK, Torrekens S, Roth SI, Mackem S, Carmeliet G, Kronenberg HM. Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev Cell. 2010;19:329–344. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma’ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignone JL, Kukekov V, Chiang AS, Steindler D, Enikolopov G. Neural stem and progenitor cells in nestin-GFP transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:311–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.10964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi T, Ahmed J, Kunisaki Y, Pinho S, Ono N, Kronenberg HM, Frenette PS. Osterix marks distinct waves of primitive and definitive stromal progenitors during bone marrow development. Dev Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.013. (this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokry J, Cizkova D, Filip S, Ehrmann J, Osterreicher J, Kolar Z, English D. Nestin expression by newly formed human blood vessels. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:658–664. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382:635–638. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura E, Nguyen MT, Mackem S. Kinetics of tamoxifen-regulated Cre activity in mice using a cartilage-specific CreER(T) to assay temporal activity windows along the proximodistal limb skeleton. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2603–2612. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto F, Thornell AP, Crompton T, Denzel A, Gilmour KC, Rosewell IR, Stamp GW, Beddington RS, Mundlos S, Olsen BR, Selby PB, Owen MJ. Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell. 1997;89:765–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovchinnikov DA, Deng JM, Ogunrinu G, Behringer RR. Col2a1-directed expression of Cre recombinase in differentiating chondrocytes in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2000;26:145–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodda SJ, McMahon AP. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development. 2006;133:3231–3244. doi: 10.1242/dev.02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, Di Cesare S, Piersanti S, Saggio I, Tagliafico E, Ferrari S, Robey PG, Riminucci M, Bianco P. Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell. 2007;131:324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Jacques B, Hammerschmidt M, McMahon AP. Indian hedgehog signaling regulates proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes and is essential for bone formation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2072–2086. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabova L, Yamada SS, Wimer H, Chrysovergis K, Ingvarsen S, Behrendt N, Engelholm LH, Holmbeck K. MT1-MMP and type II collagen specify skeletal stem cells and their bone and cartilage progeny. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1905–1916. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.090510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teranishi N, Naito Z, Ishiwata T, Tanaka N, Furukawa K, Seya T, Shinji S, Tajiri T. Identification of neovasculature using nestin in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:593–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski J, Engstrom M, Edwall-Arvidsson C, Sjoberg G, Sejersen T, Lendahl U. Distribution of nestin in the developing mouse limb bud in vivo and in micro-mass cultures of cells isolated from limb buds. Differentiation. 1997;61:151–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1997.6130151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, Huang H, He X, Tong WG, Ross J, Haug J, Johnson T, Feng JQ, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.