Abstract

The purpose of the study is to investigate the effects of electrospun fiber diameter and orientation on differentiation and ECM organization of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs), in attempt to provide rationale for fabrication of a periosteum mimetic for bone defect repair. Cellular growth, differentiation, and ECM organization were analyzed on PLGA-based random and aligned fibers using fluorescent microscopy, gene analyses, electron scanning microscopy (SEM), and multiphoton laser scanning microscopy (MPLSM). BMSCs on aligned fibers had a reduced number of ALP+ colony at day 10 as compared to the random fibers of the same size. However, the ALP+ area in the aligned fibers increased to a similar level as the random fibers at day 21 following stimulation with osteogenic media. Compared with the random fibers, BMSCs on the aligned fibers showed a higher expression of OSX and RUNX2. Analyses of ECM on decellularized spun fibers showed highly organized ECM arranged according to the orientation of the spun fibers, with a broad size distribution of collagen fibers in a range of 40nm to 2.4µm. Taken together, our data support the use of submicron-sized electrospun fibers for engineering of oriented fibrous tissue mimetic, such as periosteum, for guided bone repair and reconstruction.

Keywords: Electrospinning, Extracellular Matrix (ECM), periosteum

Introduction

Tissue engineering holds enormous potential to provide functional substitutes for damaged tissues. A key component of tissue engineering is to fabricate man-made substitutes (scaffolds) to guide the regenerative process of the damaged tissue. While underlying cellular mechanisms for functions may vary greatly in different tissue types, all engineered materials must closely mimic the natural tissue environment to successfully meet or perhaps surpass the original mechanical, structural, and functional properties. To this end, providing biological and structural cues that mimic the complex properties of the native tissue has become an essential element in the design of tissue-engineering scaffolds.

Electrospinning has emerged as a mainstay in tissue engineering due to its versatility in fabricating randomly oriented or aligned fibers that are characteristic of the extracellular matrix (ECM).1,2 Electrospinning is used to draw micron- and nanometer-sized nonwoven fibers through the electrostatic interactions of the charged polymers. Fibers produced from this technique exhibit high uniformity and mechanical strength and form porous scaffolds with a high surface-to-volume ratio.3 A wide range of synthetic biodegradable polymers as well as natural macromolecules have been used to create fibrous scaffolds.4–7 Although electrospun natural polymers show higher hydrophilicity, synthetic polymers are more robust and present higher mechanical properties.8 Scaffolds consisting of synthetic electrospun fibers can be further functionalized for enhanced cellular activities by incorporating compounds or morphogens such as hydroxyapatite,9 glycosaminoglycan,10 and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2.11 Release of these compounds from the scaffolds can be controlled by careful blending of different synthetic biodegradable polymers.12,13 By offering both topographical and biochemical signals, the electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds may provide an optimal microenvironment mimicking native ECM for the seeded cells. With the development of increasingly complicated techniques, electrospinning has become not only a versatile tool for fabrication of various tissues, but also a valuable approach for understanding the complex tissue-specific microenvironment for biomimetic tissue regeneration.14

Although electrospun fibers have been explored in bone tissue engineering,15–115-17 the application is perhaps best suited for fabrication of a multilayered membranous type of tissue mimicking periosteum for bone graft repair and reconstruction.18–20 The versatile electrospinning technique will allow creation of a multilayered membrane simulating the highly organized ECM in periosteum.21,22 Combined with adequate progenitor cell populations and molecular signals, this biomimetic fibrous membrane could be used as a periosteum replacement for bone defect repair and reconstruction. To further understand the design specifics for this application, electrospun fibers of different diameters and orientation were created using a modified electrospinning technique. The impact of the synthetic fiber topology, specifically the fiber diameter and orientation on osteogenic differentiation and ECM organization, was examined using bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) isolated from a GFP transgenic mouse model.

Materials and Methods

Electrospinning

Electrospun fibrous scaffold was fabricated using a modified magnetic-field-assisted-electrospinning procedure as described previously.23 Poly (D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) with 75:25 monomer ratios between lactic and glycolic acids were purchased from Lactel Absorbable Polymers (Pelham, AL). 1, 1, 1, 3, 3, 3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFP) with 99+% purity (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) was used as the solvent for all polymers. Homogenous polymer solutions in HFP were prepared by stirring overnight at room temperature. The concentrations of the polymer from 10 to 20g/100mL were used. Briefly, a 10-mL syringe with a 22G1½ needle (BD, Bedford, MA), used as a solution reservoir and a spinneret, respectively, was attached to a syringe pump (Chemyx Incorporation, Houston, TX). The tip of the needle was connected to a high-voltage power supply (Gamma High Voltage Research, Ormond Beach, FL). The applied voltage and flow rate of the pump were kept constant during an electrospinning session. To minimize possible effect of air flow on electrospinning, the collection area was kept inside a custom-made polycarbonate box (35 cm × 35 cm × 40 cm). Nonstick aluminum foil was used to collect deposited fibers. Needle-to-collector distance was kept at 12 cm. A pair of ceramic block magnets (4.8 cm × 2.2 cm × 0.95 cm; Hillman, Cincinnati, OH) covered in aluminum foil was used for generating aligned fibers. The pore size of the scaffold, as determined by analyses using Image J, ranges from 100nm to 50nm. For all in vitro analyses, a single layer 2×2 cm fibrous membrane was glued to the bottom of the 6-well culture plate for cell seeding.

Isolation of BMSCs

Bone marrow cells were isolated from 2-month-old transgenic mice engineered to express GFP ubiquitously as previously described.24 The use of a GFP transgenic mouse model allows easy tracking of the cells using fluorescence-based microscopic techniques in vitro. Briefly, femora and tibiae were removed aseptically and dissected free of adherent soft tissue. The bone ends were cut, and bone marrow cells were flushed from the marrow cavity by injecting alpha-MEM medium slowly at one end of the bone using a sterile 21-gauge needle. About 5×106 recovered bone marrow cells were seeded on sterile electrospun fibers in 6-well plates and cultured in alpha-MEM media containing 15% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT) for 10 days. Osteogenic differentiation media containing 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, 5mM β-glycerophosphate, and 10% FBS in alpha-MEM was added at day 10 and cultured for additional 21 days.

Analysis of the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs

An inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL) was used to examine the attachment, growth, and differentiation of the murine BMSCs. To determine whether the cultured BMSCs were capable of differentiating into osteoblastic lineage on the scaffolds, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining was performed on day 10, 15 and 28 following seeding.19 Stained scaffolds at day 10, 15, and day 21 were photographed by a digital camera mounted on a microscope (Olympus SZX12). The numbers of ALP+ colonies on the fiber mesh were recorded and manually counted. The areas of the ALP+ region were quantified using Image J.24 To determine osteogenic gene expression, total RNA was isolated from day 10 and day 21 cultures. Quantitative real-time PCR analyses were performed to examine RUNX2 and OSX expression as previously described.25,26 Three separate experiments were performed to determine osteogenic differentiation on different scaffolds.

Scanning electron microscope

Field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; Carl Zeiss NTS GmbH; Model: SUPRA™ 40VP) was used for characterization and analysis of fiber morphology. All samples were mounted onto imaging stubs and sputter-coated with gold for 40 seconds (Desk –, Denton Vacuum). Images were taken at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV using the InLens mode. The specimens used for imaging the cross-sections of electrospun fibers were made by freezing the sample in liquid nitrogen for 5 min, followed by cutting with a sharp knife. Data are expressed as a mean value plus or minus the standard deviation of the mean.

Analyses of the size distribution of collagen fibril/fiber in ECM

Analyses of the thickness of collagen fibril/fiber were performed on seeded scaffolds at day 21. Cells on the scaffold were removed by incubating a mixture of 0.5% Triton X and 20 mM NH4OH for 5 minutes at room temperature.27 The remaining matrix and scaffolds were mounted and imaged by SEM. Measurements of collagen fiber diameter were made on at least 5 images of the ECM obtained from three samples at 5000× magnification. The average thickness of the fibers was calculated via Image J (Bethesda, MD, USA) using a methodology described by Dougherty et al.28 The fiber size distribution was plotted based on raw data extracted from Image J plug-ins. In some cases, a mean was calculated based on the manual measurements of at least 50 collagen fibers at the different regions of the scaffold using build-in software in SEM.

Multiphoton laser scanning microscopy (MPLSM)

A multiphoton microscope (Olympus Fluoview 1000 AOM-MPM) was used to image the cells and native collagen matrix in the scaffolds. Using the excitation wavelength 780 nm to generate multiphoton excitation signals from GFP, and second harmonic generation (SHG) signals from collagen at 390 nm, BMSCs and ECM were detected simultaneously on cultured cellular scaffolds. Three-dimensional images were reconstructed via Amira imaging software (VSG, Burlington, MA). The diameters of the collagen fibers were directly measured using Image J. The means were determined based on at least 50 fibers at different regions of the substrate.

Statistical analyses

Data were expressed as a mean value plus or minus the SEM. Statistical significance between experimental groups was determined using one-way analysis of variance and a Tukey's post hoc test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

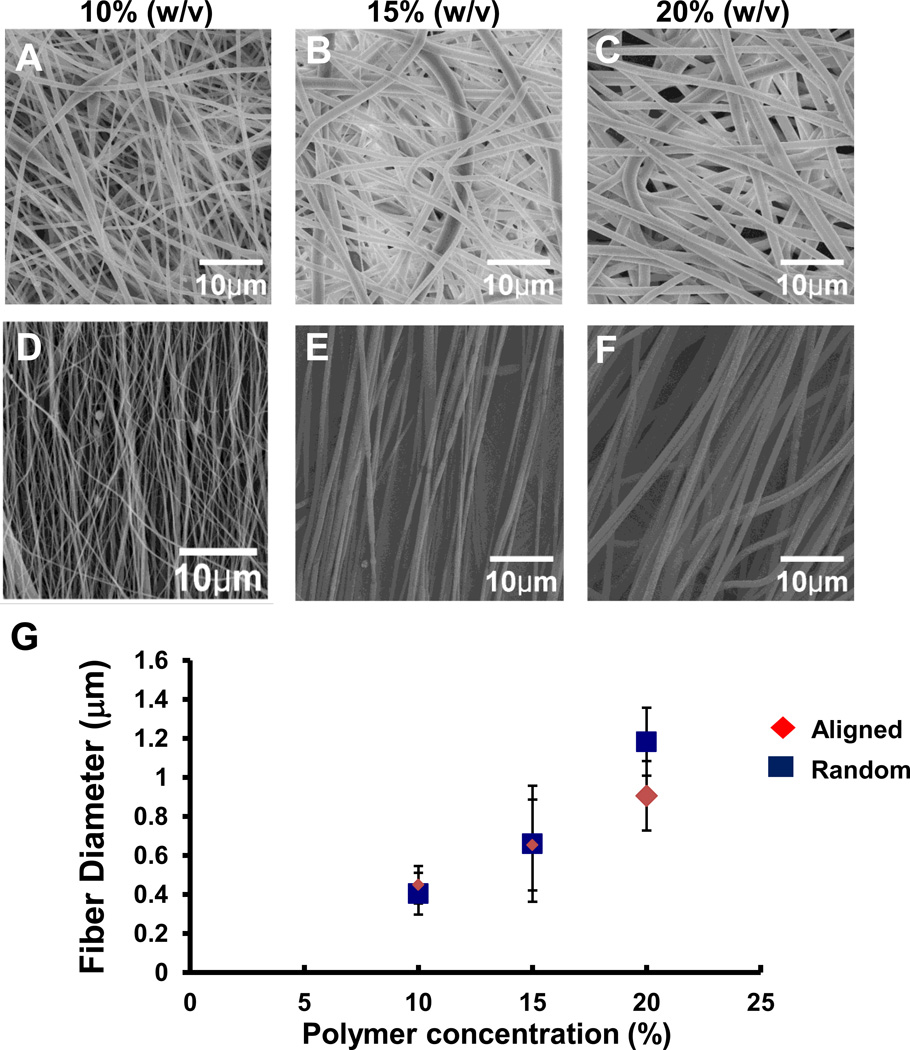

By varying the concentration of the polymer solution, fibrous scaffolds with different fiber diameters were obtained by electrospinning. Characterization of the fibers showed a near linear relationship between fiber diameters and the polymer concentration at 10%, 15%, and 20%. As the concentration of the polymeric solution increased, the resulting fiber diameter increased for both aligned and random fibers (Fig. 1). At a lower or higher concentration outside the range, deformation of the fiber such as beading and branching occurred, compromising the uniformity of the as-spun fibers. Based on the synthetic fiber diameters and orientation, four groups of fibers were selected for detailed analyses on cellular attachment and differentiation: 1) aligned fibers from 10% polymer solution with a diameter of 404±107; 2) aligned fibers from 20% polymer solution with a diameter of 906±178; 3) random fibers created from 10% polymer solution with a diameter of 449±96; and 4) random fiber from 20% polymer solution with a diameter of 1183±174. Fibers created from 15% polymer solution displayed an overlapping diameter range with those from both 10% and 20% solution (Fig. 1), and therefore were excluded from the analyses.

Fig. 1.

A–G Representative SEM images showing randomly oriented (A–C) and aligned (D–F) electrospun fibers fabricated at a concentration of 10% (A, D), 15% (B, E), and 20% (C, F) 75:25 PLGA. The means of the fiber diameter are directly correlated with the indicated concentrations of polymer (w/v) for both aligned and random fibers (G).

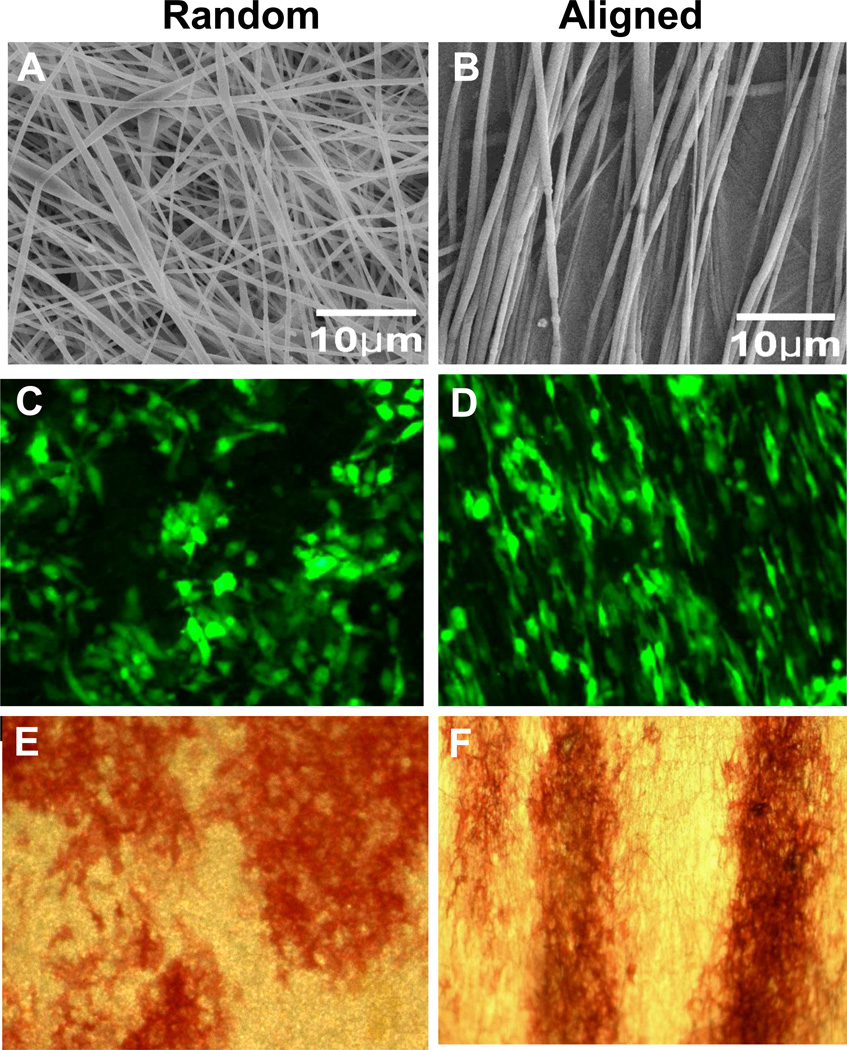

Fluorescence imaging showed attachment of GFP-tagged BMSCs on both aligned and randomly oriented PLGA scaffolds (Fig. 2). Cells on aligned fibers showed more elongated and spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 2D) compared with the ones on randomly oriented fibers, which were more spherical (Fig. 2C). Cells on aligned fibers oriented themselves along the direction of the fibers. ALP staining showed that both aligned and randomly oriented scaffolds supported osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. On randomly oriented fibrous scaffold, the ALP-positive colonies were irregularly shaped (Fig. 2E). On aligned fibrous scaffold, ALP-positive colonies existed in strips, suggesting directional guidance from the electrospun fibers (Fig. 2F). When ALP staining was performed on day 10, more ALP-positive colonies were found on the random fibers than the aligned fibers (Fig. 3A and B). This difference was observed regardless of the fiber diameters. Real-time PCR analyses further showed that at day 10 following seeding, BMSCs exhibited reduced expression of OSX on aligned fibers (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, after additional 11 days of culture in osteogenic medium, ALP staining was markedly induced in both aligned and random fiber groups (Fig. 3A). Measurements of the area of ALP+ regions at day 21 showed similar differentiation on all 4 types of fibers (Fig. 3C). Quantitative real time PCR showed marked induction of OSX and RUNX2 expression in day 21 cultures as compared to day 10 (Fig. 3D and E), with aligned fibers exhibiting higher expression of OSX and RUNX2 (p<0.05). All 4 types of fibers within a diameter range of 300–1300 nm supported osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs.

Fig. 2.

A–F SEM analyses show distinctive topology of random (A, 1000×) or aligned (B, 1000×) PLGA fibers. Fluorescence images of GFP-tagged murine bone marrow stromal cells cultured on both types of fibers show distinctive morphology. Cells on randomly fibers adopted a rounder morphology (C, 25×) whereas cells on aligned fibers were elongated (D, 25×). ALP-positive colonies on scaffolds at day 10 displayed a similar morphology on random (E, 4×) and aligned fibers (F, 4×).

Fig. 3.

A–E Alkaline phosphatase staining were performed on random and aligned fibers on days 10, 15 and 21 as indicated (A). Photographs of the colony formation on fibrous meshes were taken at a magnification of 1× via a dissection microscope. Numbers of the ALP+ colony were quantified at day 10 (B) and areas of the ALP+ region were quantified at day 21 (C). Real time PCR analyses show osteogenic marker gene OSX (D) and RUNX2 (E) expressions at day 10 and day 21. * indicate p<0.05.

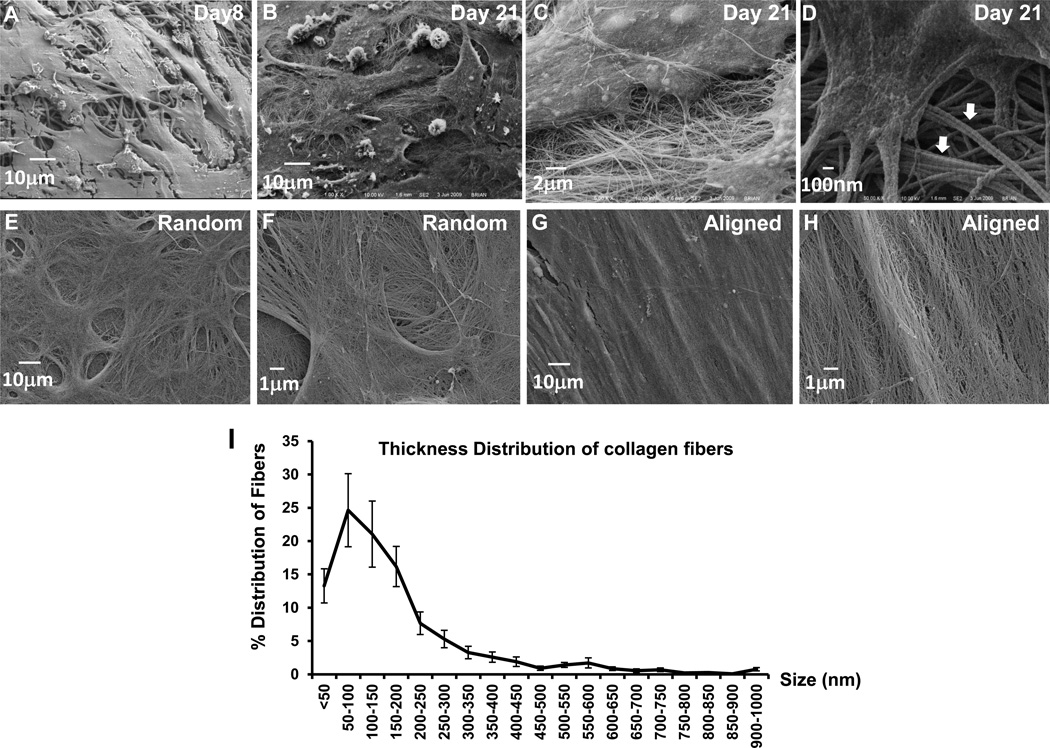

High resolution analyses using SEM revealed detailed interactions between BMSCs and the electrospun fibers during cellular differentiation. On Day 8, BMSCs showed attachment and growth into the fibrous PLGA scaffold (Fig. 4A). By Day 21, BMSCs were found to be embedded within cell-derived ECM that covered the entire scaffold (Fig. 4B). On randomly reoriented scaffold, collagen fibers were seen extending from all directions from the polygonal cells (Fig. 4B–C). These fibers were formed through bundling of the thin collagen fibrils. Examination of these thin collagen fibrils at a higher magnification showed characteristic banded repeats with typical uniformity (Fig. 4D).29 Measurement of the collagen fibrils showed a narrow diameter distribution with a mean of 41 and a standard deviation of 8 nm. Following decellularization to remove cells, SEM showed that the scaffold was covered with native collagen matrix produced by BMSCs (Fig. 4E–H). The orientation of the large collagen fibers or collagen bundles were organized according to the alignment of the electrospun polymeric fibers. The collagen matrix adopted a swirling morphology on randomly oriented polymeric fibers (Fig. 4E–F). On the aligned polymeric fibers, the collagen fibers were organized along the longitudinal direction of the polymeric fibers (Fig. 4G–H). Thin collagen fibrils appeared to be woven in between the large collagen fibers/bundles. Analyses of the thickness of collagen fibers in BMSC cultures showed a broad range of distribution from 35 to 1000 nm (Fig. 4I). Image analyses from three samples revealed an average diameter of 143nm.

Fig. 4.

A–H Representative SEM images (×1000) of bone marrow stromal cells cultured on randomly oriented electrospun fibers on Day 8 (A) and Day 21 (B). Higher magnification image (×10,000) shows detailed morphology of and nano and micron-sized collagen matrix with polygonal cells (C). Characteristic collagen fibrils and collagen bundles (arrows) are shown at ×30,000 (D). Following removal of the cells (decellularization), the native collagen matrix produced by BMSCs cultured on randomly oriented (E, F) or an aligned fibers (G, H) is shown at ×1000 and ×5000.

MPLSM analyses in the living cultures of BMSCs (Fig. 5) showed that cells (shown as green in Fig. 5A, B, E, F) occupied the synthetic fiber network and constructed their own collagen matrix in the surroundings (shown as cyan in Fig. 5C, D, G, H). The majority of the cells were spread and differentiated on the surface of the fibrous scaffold (Fig. 5A and B). Infiltration of cells into the deeper region of the polymeric fibers can be found in both random and aligned fibrous meshes at 50µm depth (Fig. 5E and F). Consistently with the previous finding in SEM, BMSCs and collagen matrix were arranged according to the orientation and alignment of the electrospun fibers (Fig. 5A, C, E, G vs. B, D, F, and H). On the random fibers, BMSCs formed “honeycomb”-like matrix with cells dwelling inside (Fig. 5C and G). In cultures on the aligned fibers, cells as well as the matrix were organized into strips (Fig. 5D and H). Analyses of the collagen fiber diameter using image J showed the coexistence of both high-contrast nano- and micro-scaled collagen fibers produced from BMSCs. Measurements of the distinctive thicker fibers showed a mean diameter of 1.786±0.6 µm (n=85). These thicker fibers formed an extended nest surrounding the cells. The decellularization procedure allowed removal of the cells without disruption of the overall morphology of the ECM produced from BMSCs in both random and aligned fibers (Fig. 5G and H).

Fig. 5.

A–D Fluorescent excitation and SHG of live GFP-positive cells cultured on random or aligned fibers were imaged via MPLSM at day 21. Cells are shown as green and collagen matrix produced by these cells shown as cyan. Distinctive cellular morphology and collagen matrix organization are shown in randomly oriented (A, C, E, G) and aligned (B, D, F, H) fibers. Multiphoton microscopy further allows optical sectioning of the live specimens at a depths of 5um (A–D, surface layer) and 50 um (E and F, deeper layer). G and H show collagen matrix in random or aligned decellularized electrospun fibers.

Discussion

We have previously demonstrated a tissue-engineering approach that combines structural bone graft, genes, and BMSCs in a murine model to repair a large segmental defect.18,19,30 A major limitation to the translation of this approach is the lack of a cellular osteoinductive scaffold that could function as periosteum to fit around a bone of any size or shape. Electrospun nanofibers have offered a versatile technique for fabrication of a biomimetic scaffold best suited for such an application. To provide further rationales for the use of electrospun fibers as a scaffolding platform for fabrication of a periosteum replacement, we performed a series of in vitro experiments to determine the impact of fiber diameter and orientation on cellular differentiation and ECM organization of BMSCs. Our studies showed that the orientation of the fibers had a significant impact on the differentiation of BMSCs and the organization of ECM. Using oriented electrospun fibers could provide significant advantages for guided bone tissue repair and reconstruction.

While the electrospun fibrous scaffolds have been shown to support cellular attachment, proliferation, and differentiation in a variety of cell types, the impact of fiber diameter and fiber orientation on osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs has not been well characterized. Careful examination of the literature shows contradictory results or ambiguous descriptions in regards to the effects of alignment and fiber diameter on the differentiation of BMSCs.31–36 An earlier report using MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cell line shows that the fiber diameter affects cellular density at the early stage of osteoblastic differentiation.35 Following addition of osteogenic differentiation media, cell density and differentiation become comparable in fibers ranging from 0.5–2 µm. Other reports using various polymeric materials show conflicting results in cultures.31–35 In our current study, in which freshly isolated bone marrow stromal cell cultures were used, we found that fiber diameter at a range of 300–1200nm had a minimal effect on differentiation of BMSCs. However, at the same diameter range, fiber orientation significantly impacted the early behavior and differentiation of BMSCs. Cells cultured on aligned fibers had a reduced number of ALP+ colony at day 10, indicating a slight delay in early osteoblastic differentiation. However, this negative effect on differentiation could be overcome by the addition of osteogenic differentiation media containing ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate, such that by day 21 the cells on aligned fibers exhibited higher levels of RUNX2 and OSX gene expression. These results show that the aligned fibers of nano and sub-micron size could be used as a suitable scaffolding platform to support the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs.

Two complementary imaging technologies were used to analyze ECM deposition on the electrospun fibers. While both SEM and MPLSM allow analyses at high resolution, SEM only permits high resolution imaging of the surfaces. In comparison, MPLSM offers a significant advantage in analyzing fluorescence labeled cells throughout the fiber mesh in living cultures. MPLSM further allows visualization of collagen-rich ECM via Second Harmonic Generation (SHG). SHG is produced in the noncentrosymmetric biomolecules such as collagen fibrils or collagen fiber in ECM. SHG is enhanced when disordered collagen triple helices are converted into ordered fibrils and further compacted into collagen fibers.37–40 SHG microscopy has been widely used for visualization and assessment of tissue structure in wound healing, malignancy, and development.41–43 As an intrinsic signal from the collagen, measurement of SHG overcomes variability and uncertainty that are often associated with immunohistochemical staining.39,40

The analyses of the native ECM showed that the ECM deposited on the fibrous scaffolds was organized largely according to the orientation of the polymeric fibers.44–51 This important feature could be used to produce highly organized ECM of the native tissues, such as periosteum during healing. Although the detailed microstructure of periosteum remains elusive, early study of periosteum in chick calvaria shows that periosteum explant forms densely packed, highly oriented, crossbanded collagen fibrils prior to mineralization,22 suggesting highly organized collagen matrix formation prior to bone formation. A recent study from Foolen et al. further shows that collagen orientation in periosteum and perichondrium is aligned with preferential directions of tissue growth.21 Our unpublished data indicated that the collagen fiber arrangement at the cortical bone gap consisted of multilayered, crisscrossing, and highly oriented collagen bundles. The unique arrangement of the collagen fibers at the site of repair suggests the necessary guidance cues for directional growth and migration of progenitor cells during repair and reconstruction. In support of this notion, several recent studies indicate that the spatially oriented electrospun fibers could serve as a guidance substrate for wound repair. MSCs migrate faster along oriented fibers than non-oriented counterparts.52,53 Thus, from a biomimetic standpoint, electrospun fiber with its versatility in producing patterned ECM could be used as a bonding matrix that bridges damaged bone tissues, providing necessary cues for guided bone tissue repair and reconstruction.

While submicron to micro-sized polymeric fibers were shown to effectively support BMSC growth and differentiation, analyses of the native ECM/collagen matrix indicated that the majority of collagen fibers (74%) deposited by BMSCs had a diameter range of 35 to 200nm, significantly smaller than polymeric fibers generated via electrospinning. Spun fibers in nanometer scale could be produced using our current method. However, as previously reported the uniformity of fibers in the order of 50–200nm were often compromised due to beading and branching.54 To overcome this, we demonstrated an ECM-coated spun fiber-based scaffold created by removal of the cells from the seeded fiber meshes (Fig. 4E–H). These decellularized matrices maintained the spatial orientation of the synthetic fibers with newly deposited collagen fibers organized according to the instructive cues of the synthetic fibers. These ECM coated polymeric fibers combine the benefits of ECM, such as the rich content of growth factors for cell proliferation and differentiation,27,55,56 and the direction guidance of aligned synthetic fibers, therefore could provide advantages for progenitor cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation in a more suitable bone healing microenvironment. The efficacy of these native ECM-coated electrospun fibrous scaffolds for repair and reconstruction is currently under investigation.

Although electrospinning still faces issues such as control of porous structure, cell infiltration, and fiber degradation, its versatility and simplicity in producing patterned and oriented nano and submicron-sized fibers has provided distinctive advantages in scaffold design and fabrication. Many recent advances such as co-axial or core-shell electrospinning, two-phase electrospinning, simultaneous cell-spraying, and electrospinning of nanoparticle-incorporated polymers suggest that there is a tremendous potential for this technique in tissue engineering.57–62 With such methods as blowing-assisted or multi-jet electrospinning, a large industry-scale production of electrospun fibers for clinical use is also conceivable.63

In summary, using a versatile electrospinning technique that allows fabrication of polymeric fibers with controlled uniformity and alignment, in this study, we examined the impact of fiber diameter and orientation on BMSC differentiation and ECM deposition in vitro. Our data demonstrated an advantage of using oriented and organized nano- and submicron- fibers as a scaffolding platform for engineering periosteum mimetics for bone tissue repair and reconstruction.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by grants from the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation (XPZ), NYSTEM N08G-495 (XPZ) and N09G346 (XPZ), and the National Institutes of Health (R21 DE021513 to XPZ, RC1AR058435 to XPZ, AR051469 to XPZ). We thank Ming Xue for her assistance in isolation of bone marrow stromal cells from GFP transgenic mice.

References

- 1.Ma Z, Kotaki M, Inai R, Ramakrishna S. Potential of nanofiber matrix as tissue-engineering scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:101–109. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumbar SG, James R, Nukavarapu SP, Laurencin CT. Electrospun nanofiber scaffolds: engineering soft tissues. Biomed Mater. 2008;3:034002. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li D, Xia Y. Electrospinning of Nanofibers: Reinventing the Wheel? Advanced Materials. 2004;16:1151. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlin RL, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Polymeric nanofibers in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2011;17:349–364. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holzwarth JM, Ma PX. Biomimetic nanofibrous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9622–9629. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prabhakaran MP, Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L, Ramakrishna S. Electrospun composite nanofibers for tissue regeneration. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2011;11:3039–3057. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2011.3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong S, Zhang Y, Lim CT. Fabrication of large pores in electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for cellular infiltration: A review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2011.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gee AO, Baker BM, Silverstein AM, et al. Fabrication and evaluation of biomimetic-synthetic nanofibrous composites for soft tissue regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:803–813. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madurantakam PA, Cost CP, Simpson DG, Bowlin GL. Science of nanofibrous scaffold fabrication: strategies for next generation tissue-engineering scaffolds. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2009;4:193–206. doi: 10.2217/17435889.4.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanfer B, Seib FP, Freudenberg U, et al. The growth and differentiation of mesenchymal stem and progenitor cells cultured on aligned collagen matrices. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5950–5958. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li C, Vepari C, Jin HJ, et al. Electrospun silk-BMP-2 scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3115–3124. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashammakhi N, Ndreu A, Piras A, et al. Biodegradable nanomats produced by electrospinning: expanding multifunctionality and potential for tissue engineering. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6:2693–2711. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sill TJ, von Recum HA. Electrospinning: applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1989–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith LG, Swartz MA. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:211–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Martino A, Liverani L, Rainer A, et al. Electrospun scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Musculoskelet Surg. 2011;95:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s12306-011-0097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramachandran K, Gouma PI. Electrospinning for bone tissue engineering. Recent Pat Nanotechnol. 2008;2:1–7. doi: 10.2174/187221008783478608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li WJ, Laurencin CT, Caterson EJ, et al. Electrospun nanofibrous structure: a novel scaffold for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60:613–621. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Awad HA, O'Keefe RJ, et al. A perspective: engineering periosteum for structural bone graft healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1777–1787. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0312-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Xie C, Lin AS, et al. Periosteal progenitor cell fate in segmental cortical bone graft transplantations: implications for functional tissue engineering. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2124–2137. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knothe Tate ML, Dolejs S, McBride SH, et al. Multiscale mechanobiology of de novo bone generation, remodeling and adaptation of autograft in a common ovine femur model. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2011;4:829–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foolen J, van Donkelaar C, Nowlan N, et al. Collagen orientation in periosteum and perichondrium is aligned with preferential directions of tissue growth. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1263–1268. doi: 10.1002/jor.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenenbaum HC, Palangio KG, Holmyard DP, Pritzker KP. An ultrastructural study of osteogenesis in chick periosteum in vitro. Bone. 1986;7:295–302. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(86)90211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Zhang X, Xia Y, Yang H. Magnetic field-assisted electrospinning of aligned straight and wavy polymeric nanofibers. Advanced Materials. 2010;22:2454–2457. doi: 10.1002/adma.200903870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Schwarz EM, Young DA, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates mesenchymal cell differentiation into the osteoblast lineage and is critically involved in bone repair. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1405–1415. doi: 10.1172/JCI15681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Huang C, Zeng F, et al. Activation of the Hh pathway in periosteum-derived mesenchymal stem cells induces bone formation in vivo: implication for postnatal bone repair. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:3100–3111. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Q, Huang C, Xue M, Zhang X. Expression of endogenous BMP-2 in periosteal progenitor cells is essential for bone healing. Bone. 2011;48:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen XD, Dusevich V, Feng JQ, et al. Extracellular matrix made by bone marrow cells facilitates expansion of marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells and prevents their differentiation into osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1943–1956. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dougherty R, Kunzelmann KH. Microscopy & Microanalysis Meeting. Ft. Lauderdale, Florida: 2007. Computing Local Thickness of 3D Structures with ImageJ. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Provenzano PP, Vanderby R., Jr Collagen fibril morphology and organization: implications for force transmission in ligament and tendon. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie C, Reynolds D, Awad H, et al. Structural bone allograft combined with genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells as a novel platform for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:435–445. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu LX, Wang YY, Mao X, et al. The effects of PHBV electrospun fibers with different diameters and orientations on growth behavior of bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed Mater. 2012;7:015002. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/7/1/015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen JP, Chen SH, Lai GJ. Preparation and characterization of biomimetic silk fibroin/chitosan composite nanofibers by electrospinning for osteoblasts culture. Nanoscale research letters. 2012;7:170. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen JP, Chang YS. Preparation and characterization of composite nanofibers of polycaprolactone and nanohydroxyapatite for osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Colloids and surfaces. B, Biointerfaces. 2011;86:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bashur CA, Shaffer RD, Dahlgren LA, et al. Effect of fiber diameter and alignment of electrospun polyurethane meshes on mesenchymal progenitor cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2435–2445. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badami AS, Kreke MR, Thompson MS, et al. Effect of fiber diameter on spreading, proliferation, and differentiation of osteoblastic cells on electrospun poly(lactic acid) substrates. Biomaterials. 2006;27:596–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma J, He X, Jabbari E. Osteogenic differentiation of marrow stromal cells on random and aligned electrospun poly(L-lactide) nanofibers. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2011;39:14–25. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown EB, Campbell RB, Tsuzuki Y, et al. In vivo measurement of gene expression, angiogenesis and physiological function in tumors using multiphoton laser scanning microscopy. Nat Med. 2001;7:864–868. doi: 10.1038/89997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown EB, Boucher Y, Nasser S, Jain RK. Measurement of macromolecular diffusion coefficients in human tumors. Microvasc Res. 2004;67:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown E, McKee T, diTomaso E, et al. Dynamic imaging of collagen and its modulation in tumors in vivo using second-harmonic generation. Nat Med. 2003;9:796–800. doi: 10.1038/nm879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han X, Burke RM, Zettel ML, et al. Second harmonic properties of tumor collagen: determining the structural relationship between reactive stroma and healthy stroma. Opt Express. 2008;16:1846–1859. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condeelis J, Segall JE. Intravital imaging of cell movement in tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:921–930. doi: 10.1038/nrc1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sidani M, Wyckoff J, Xue C, et al. Probing the microenvironment of mammary tumors using multiphoton microscopy. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2006;11:151–163. doi: 10.1007/s10911-006-9021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang W, Wyckoff JB, Frohlich VC, et al. Single cell behavior in metastatic primary mammary tumors correlated with gene expression patterns revealed by molecular profiling. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6278–6288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aviss KJ, Gough JE, Downes S. Aligned electrospun polymer fibres for skeletal muscle regeneration. Eur Cell Mater. 2010;19:193–204. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v019a19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu X, Chen J, Gilmore KJ, et al. Guidance of neurite outgrowth on aligned electrospun polypyrrole/poly(styrene-beta-isobutylene-beta-styrene) fiber platforms. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94:1004–1011. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nisbet DR, Forsythe JS, Shen W, et al. Review paper: a review of the cellular response on electrospun nanofibers for tissue engineering. J Biomater Appl. 2009;24:7–29. doi: 10.1177/0885328208099086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valmikinathan CM, Hoffman J, Yu X. Impact of Scaffold Micro and Macro Architecture on Schwann Cell Proliferation under Dynamic Conditions in a Rotating Wall Vessel Bioreactor. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2011;31:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bettinger CJ, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Engineering substrate topography at the micro- and nanoscale to control cell function. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:5406–5415. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lenhert S, Meier MB, Meyer U, et al. Osteoblast alignment, elongation and migration on grooved polystyrene surfaces patterned by Langmuir-Blodgett lithography. Biomaterials. 2005;26:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang JH, Grood ES, Florer J, Wenstrup R. Alignment and proliferation of MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts in microgrooved silicone substrata subjected to cyclic stretching. J Biomech. 2000;33:729–735. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang PY, Yu J, Lin JH, Tsai WB. Modulation of alignment, elongation and contraction of cardiomyocytes through a combination of nanotopography and rigidity of substrates. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:3285–3293. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu X, Wang H. Spatial arrangement of polycaprolactone/collagen nanofiber scaffolds regulates the wound healing related behaviors of human adipose stromal cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:631–642. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie J, Macewan MR, Ray WZ, et al. Radially aligned, electrospun nanofibers as dural substitutes for wound closure and tissue regeneration applications. ACS nano. 2010;4:5027–5036. doi: 10.1021/nn101554u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li L, Hsieh YL. Chitosan bicomponent nanofibers and nanoporous fibers. Carbohydr Res. 2006;341:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pei M, He F. Extracellular matrix deposited by synovium-derived stem cells delays replicative senescent chondrocyte dedifferentiation and enhances redifferentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pei M, He F, Kish VL. Expansion on Extracellular Matrix Deposited by Human Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Facilitates Stem Cell Proliferation and Tissue-Specific Lineage Potential. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madurantakam PA, Rodriguez IA, Cost CP, et al. Multiple factor interactions in biomimetic mineralization of electrospun scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5456–5464. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baker BM, Gee AO, Metter RB, et al. The potential to improve cell infiltration in composite fiber-aligned electrospun scaffolds by the selective removal of sacrificial fibers. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2348–2358. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee J, Lee SY, Jang J, et al. Fabrication of patterned nanofibrous mats using direct-write electrospinning. Langmuir. 2012;28:7267–7275. doi: 10.1021/la3009249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gupta D, Venugopal J, Mitra S, et al. Nanostructured biocomposite substrates by electrospinning and electrospraying for the mineralization of osteoblasts. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2085–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blakeney BA, Tambralli A, Anderson JM, et al. Cell infiltration and growth in a low density, uncompressed three-dimensional electrospun nanofibrous scaffold. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1583–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhong S, Zhang Y, Lim CT. Fabrication of large pores in electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for cellular infiltration: a review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:77–87. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2011.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alamein MA, Liu Q, Stephens S, et al. Nanospiderwebs: Artificial 3D Extracellular Matrix from Nanofibers by Novel Clinical Grade Electrospinning for Stem Cell Delivery. Advanced healthcare materials. 2012 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200287. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]