Abstract

The number of genetically defined Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases (PID) has increased exponentially, especially in the past decade. The biennial classification published by the IUIS PID expert committee is therefore quickly expanding, providing valuable information regarding the disease-causing genotypes, the immunological anomalies, and the associated clinical features of PIDs. These are grouped in eight, somewhat overlapping, categories of immune dysfunction. However, based on this immunological classification, the diagnosis of a specific PID from the clinician’s observation of an individual clinical and/or immunological phenotype remains difficult, especially for non-PID specialists. The purpose of this work is to suggest a phenotypic classification that forms the basis for diagnostic trees, leading the physician to particular groups of PIDs, starting from clinical features and combining routine immunological investigations along the way.We present 8 colored diagnostic figures that correspond to the 8 PID groups in the IUIS Classification, including all the PIDs cited in the 2011 update of the IUIS classification and most of those reported since.

Keywords: Primary immunodeficiency, classification, IUIS, diagnosis tool

Introduction

Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases (PID) comprise at least 200 genetically-defined inborn errors of immunity [1–3]. The International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS) PID expert committee has proposed a PID classification [1], which facilitates clinical care and clinical research studies world-wide; it is updated every other year to include new information. The PIDs are grouped into eight categories based on the principal mechanism in each disease, though if more than one mechanism is involved, there are diseases that could appear in more than one category. For each individual PID, the genotype, immunological and clinical phenotypes are briefly described. Since the number of disorders is quickly increasing every year [4–6], at an even faster pace since the advent of next-generation sequencing, the classification and these tables are therefore cumbersome. They offer limited assistance to most physicians at the bedside, especially those outside the field of PIDs and those in training; clinicians in regions of the world where awareness for PIDs is limited may also find the tables tricky.

Patients with a PID may first present to many types of medical and surgical disciplines and this is likely to be increasingly common given the growing number of patients with known or suspected PIDs [7]. Such physicians, who may lack familiarity with PIDs, need a classification that is based on a clinical and/or biological phenotype that they observe. This prompted IUIS PID experts to work on a simplified classification, based on simple clinical and immunological phenotypes, in order to provide some easy-to-follow algorithms to diagnose a particular PID or group of PIDs. This will optimize collaboration between primary centers and specialized centers, particularly for genetic studies, and will lead to faster and more precise molecular diagnosis and genetic counseling, paving the way to more appropriate management of affected patients and families. This work presents a user-friendly classification of PIDs, providing a tree-based decision-making process based on the observation of clinical and biological phenotypes.

Methodology

We included all diseases from the 2011 update of IUIS PID classification [1]. To stay up-to-date, we also included new diseases described in the last 2 years [2]. However, there may be other genes associated with PIDs that are not included here to be faithful to our inclusion criteria. An algorithm was assigned to each of the eight main groups of the classification. We used the same color for each group of similar conditions. Disease names are written in red. As in the IUIS Classification, an asterisk is added to highlight extremely rare disorders (less than 10 cases reported in the medical literature). These algorithms were first established by a small committee; then validated by one or two experts for each figure.

Results

A classification validated by the IUIS PID expert committee is presented in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8.

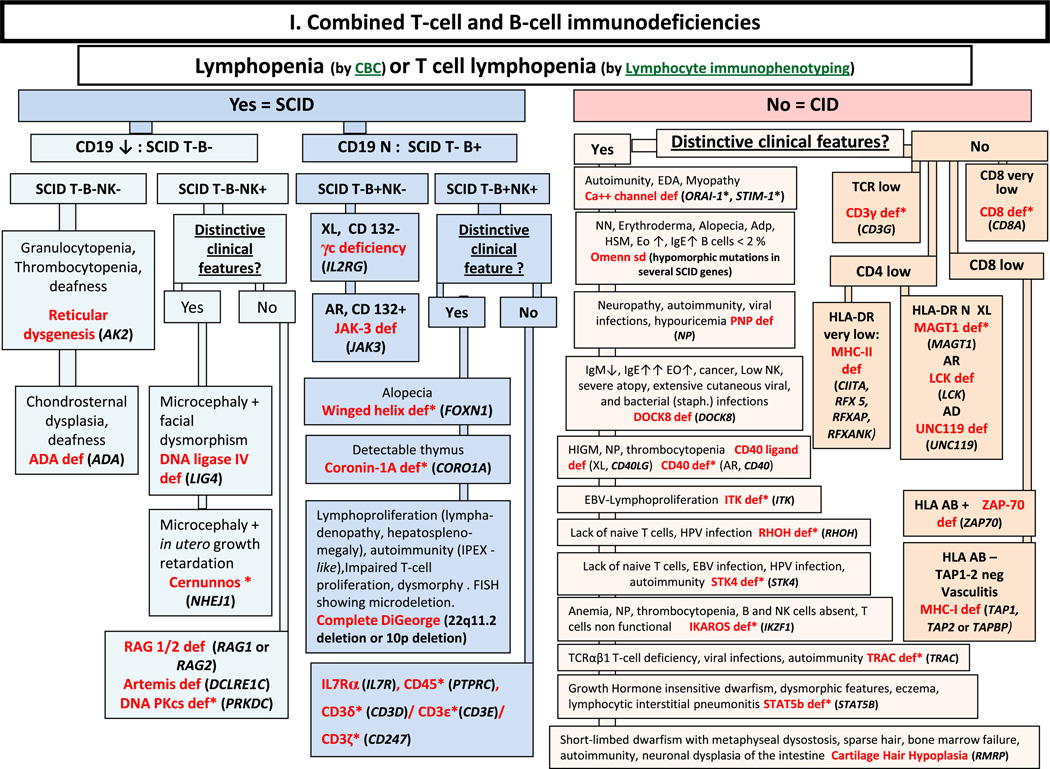

Fig. 1.

Combined T- and B- cell immunodeficiencies. ADA: Adenosine Deaminase; Adp: adenopathy; AIHA: Auto-Immune Hemolytic Anemia; AR: Autosomal Recessive inheritance; CBC: Complete Blood Count; CD: Cluster of Differentiation; CID: Combined Immunodeficiency; EBV: Ep-stein-Barr Virus; EDA: Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia; EO: Eosinophils; FISH: Fluorescence in situ Hybridization; HIGM: Hyper IgM syndrome; HLA: Human Leukocyte Antigen; HSM: Hepatosplenomegaly; Ig: Immunoglobulin; N: Normal, not low; NK: Natural Killer; NN: Neonate; NP: Neutropenia; PT: Platelet; SCID: Severe Combined ImmunoDeficiency; TCR: T-Cell Receptor; XL: X-Linked

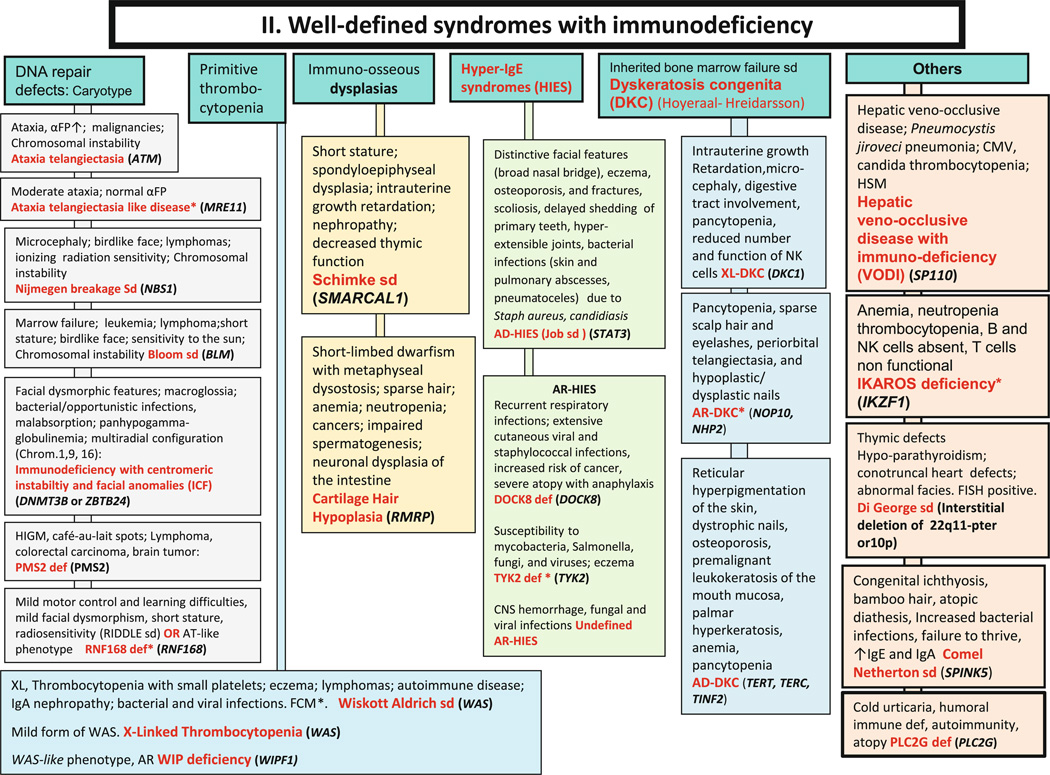

Fig. 2.

Well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiencies. These syndromes are generally associated with T-cell immunodeficiency. αFP: alpha- fetoprotein; AD: Autosomal Dominant inheritance; AR: Autosomal Recessive inheritance; CNS: Central Nervous System; FCM*: Flow cytometry available; FISH: Fluorescence in situ Hybridization; HSM: Hepatosplenomegaly; Ig: Immuno-globulin; NK: Natural Killer; XL: X-Linked inheritance

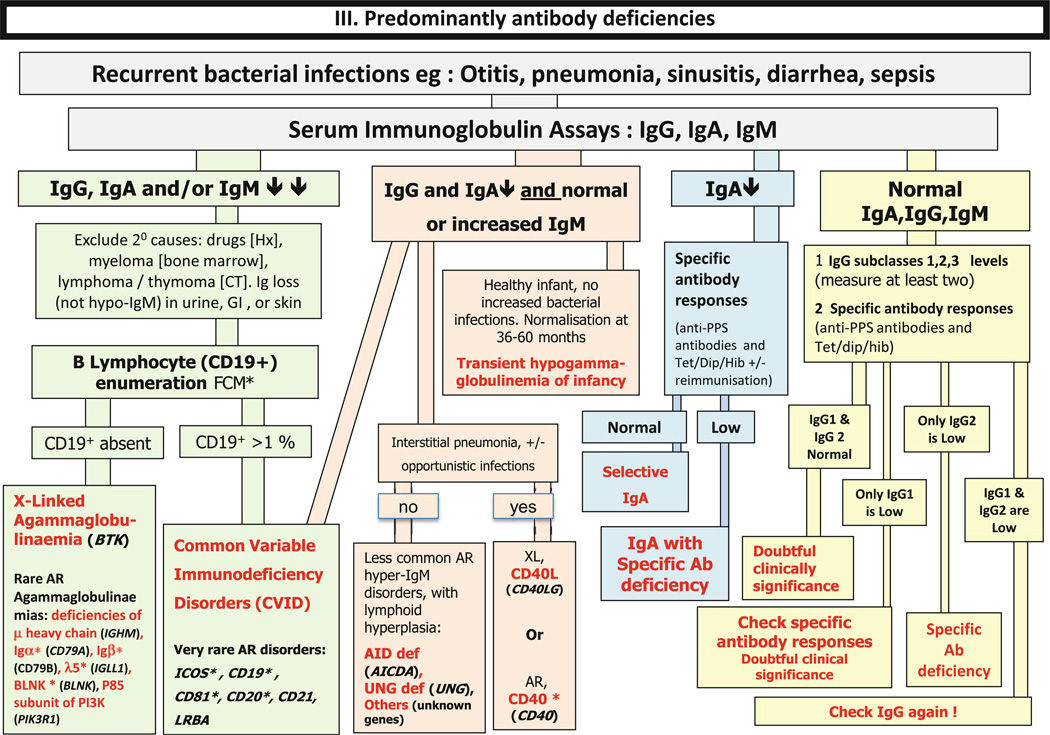

Fig. 3.

Predominantly antibody deficiencies. Ab: Antibody; Anti PPS: Anti- pneumococcal polysaccharide antibodies: AR: Auto-somal Recessive inheritance; CD: Cluster of Differentiation; CVID: Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders; CT: Computed Tomography; Dip: Diphtheria; FCM*: Flow cytometry available; GI: Gastrointestinal; Hib: Haemophilus influenzae se-rotype b; Hx: medical history; Ig: Immunoglobulin; subcl: IgG subclass; Tet; Tetanus; XL: X-Linked inheritance

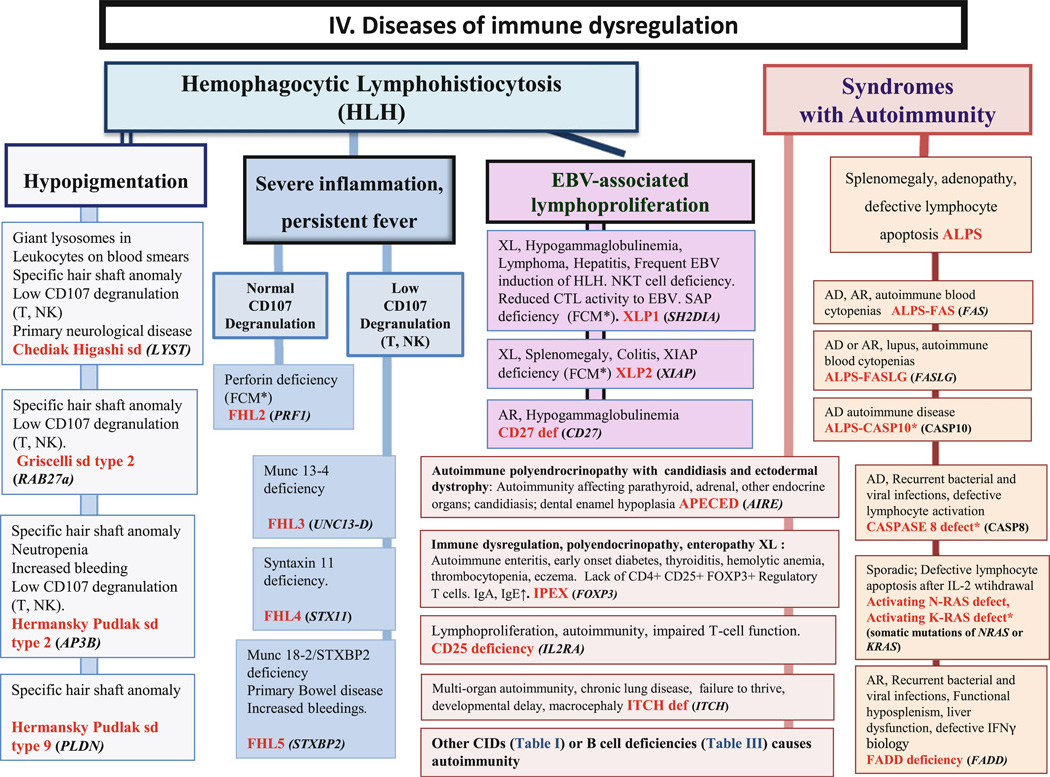

Fig. 4.

Diseases of immune dysregulation. AD: Autosomal Dominant inheritance; AR: Autosomal Recessive inheritance; CD: Cluster of Differentiation; CTL: Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte; EBV: Epstein-Barr Virus; FCM*: Flow cytometry available; HSM: Hepatosplenomegaly; Ig: Immunoglobulin; IL: interleukin; NK: Natural Killer; NKT: Natural Killer T cell; TL: T lymphocyte; XL: X-Linked inheritance

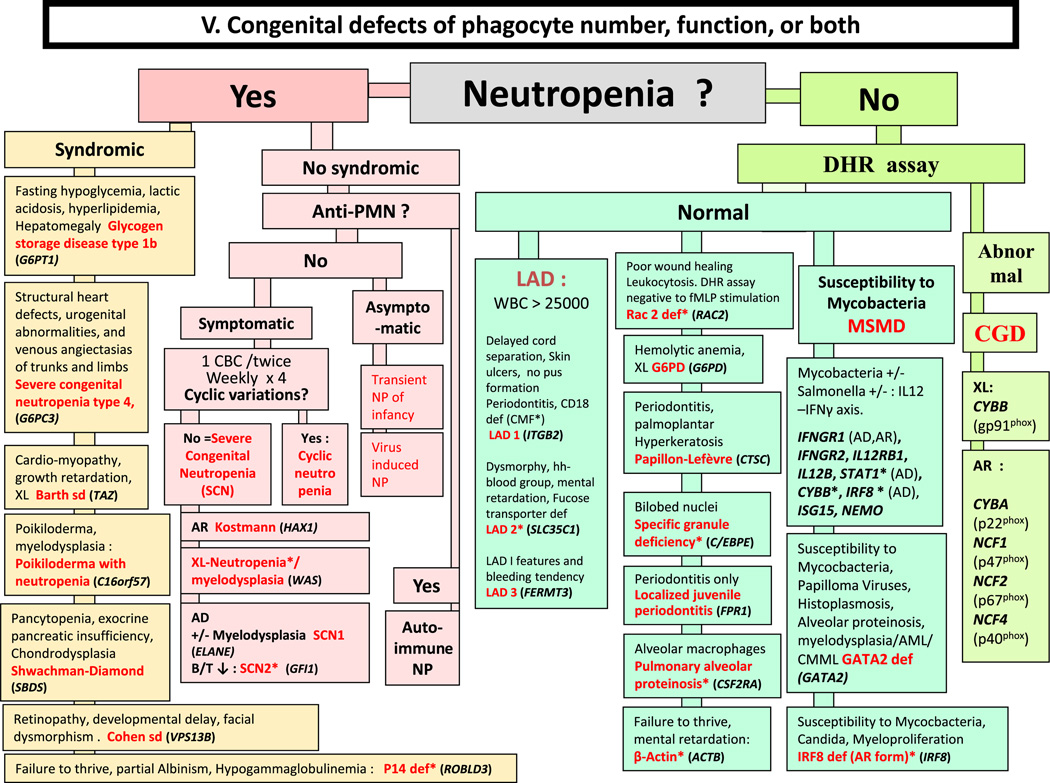

Fig. 5.

Congenital defects of phagocyte number, function, or both. For DHR assay, the results can distinguish XL-CGD from AR-CGD, and gp40phox defect from others AR forms. AD: Autosomal Dominant inheritance; AML: Acute Myeloid Leukemia; AR: Autosomal Recessive inheritance; CBC: Complete Blood Count; CD: Cluster of Differentiation; CGD: Chronic Granulomatous Disease; CMML: Chronic Myelo-monocytic Leukemia; DHR: DiHydroRhodamine; LAD: Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency; MSMD: Mendelian Susceptibility to Mycobacteria Disease; NP: Neutropenia; PNN: Neutrophils; WBC: White Blood Cells; XL: X-Linked inheritance

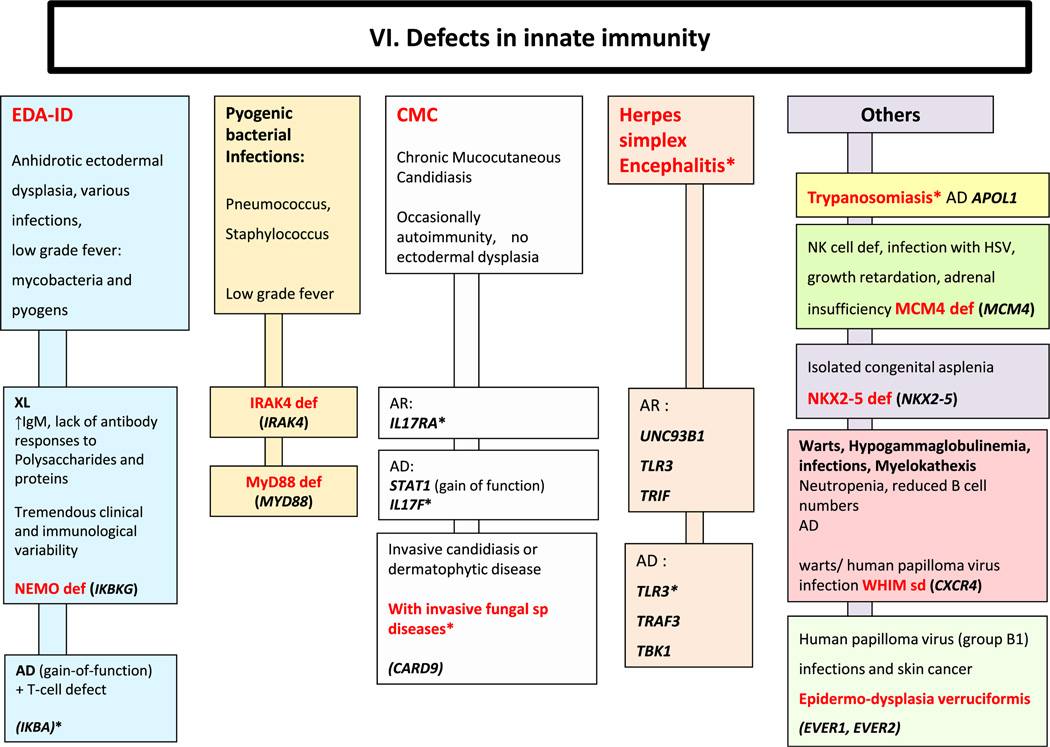

Fig. 6.

Defects in innate immunity. AD: Autosomal Dominant inheritance; AR: Autosomal Recessive inheritance; BL: B lymphocyte; EDA-ID: Anhidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia with Immunodeficiency; Ig: Immunoglobulin; PNN: Neutrophils; XL: X-Linked inheritance

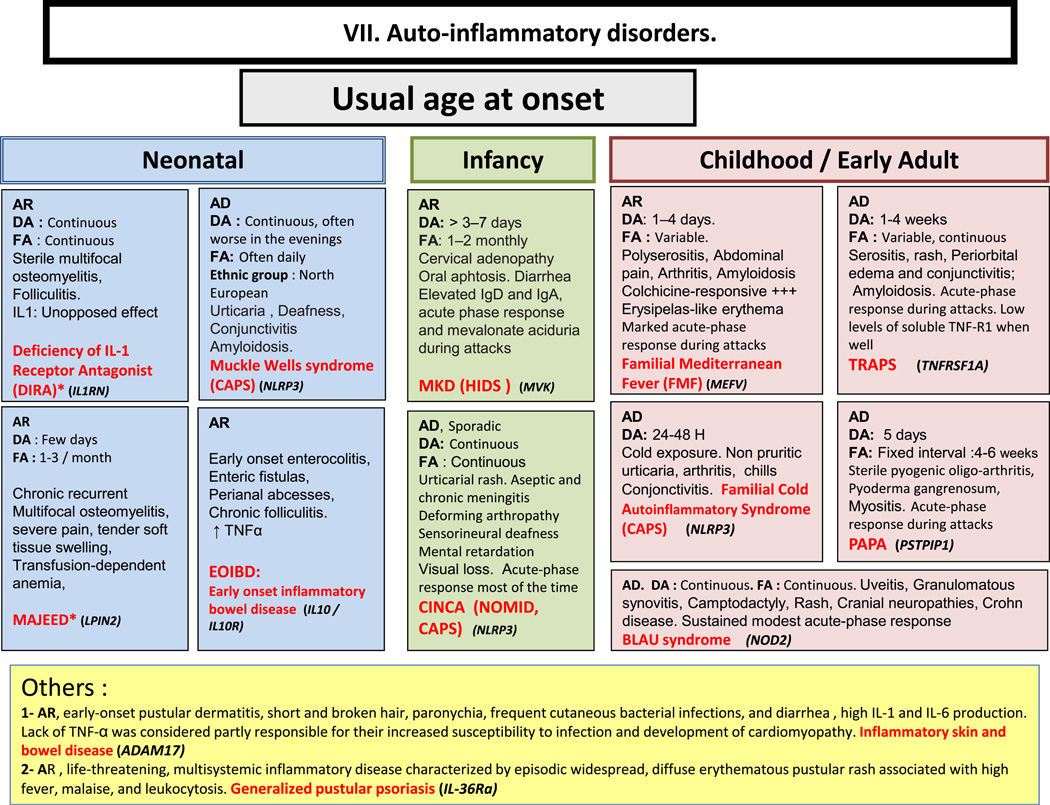

Fig. 7.

Autoinflammatory disorders. AD: Autosomal Dominant inheritance; AR: Autosomal Recessive inheritance; CAPS: Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic syndromes; CINCA: Chronic Infantile Neurologic Cutaneous and Articular syndrome; DA: Duration of Attacks; FA: Frequency of Attacks; FCAS: Familial Cold Autoinflammatory Syndrome; HIDS: Hyper IgD syndrome; Ig: Immunoglobulin; IL: interleukin; MKD: Mevalonate Kinase deficiency; MWS: Muckle-Wells syndrome; NOMID: Neonatal Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disease; PAPA: Pyogenic sterile Arthritis, Pyoderma gangrenosum, Acne syndrome; SPM: Splenomegaly; TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor; TRAPS: TNF Receptor-Associated Periodic Syndrome

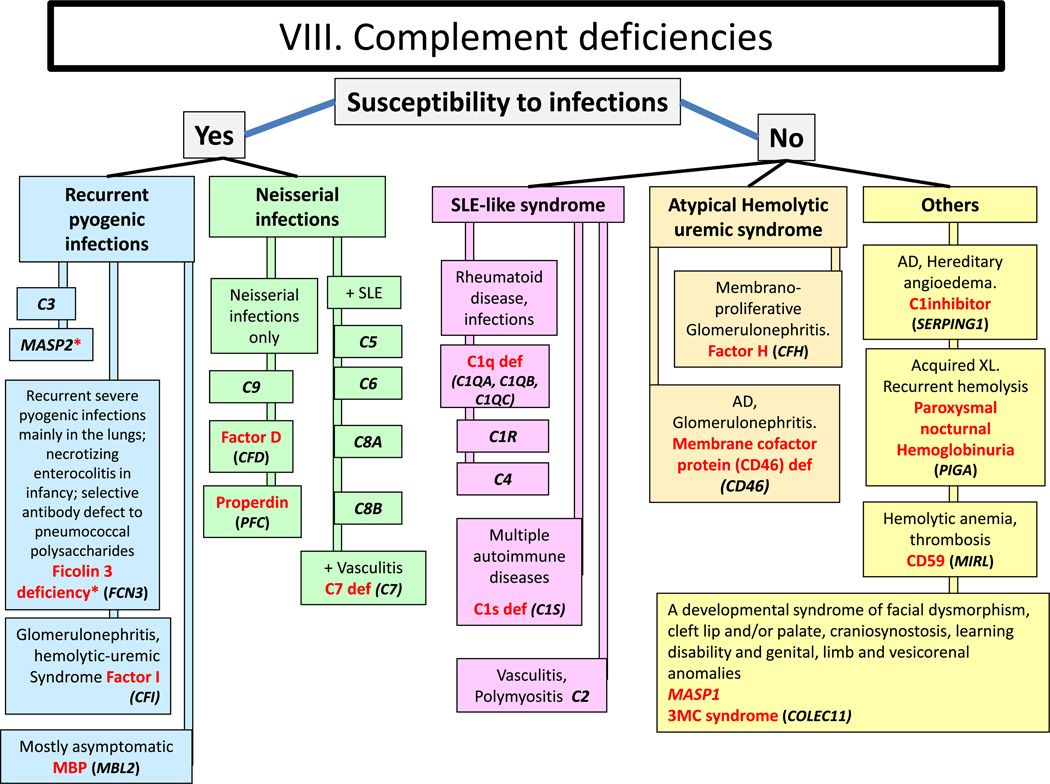

Fig. 8.

Complement deficiencies. Def: deficiency; SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Discussion

These figures are diagnostic tools that represent a modified and simplified version of the 2011 IUIS classification [1]. They are based on patients’ clinical and biological phenotypes and are mostly presented as decision trees for diagnostic orientation. These figures serve as diagnostic orientation tools for the typical forms of PID; the more atypical presentations of PIDs are not covered in these figures. These figures do not therefore aim to replace decisional trees or diagnostic protocols proposed by other teams or scientific societies [8–11]. Rather they aim at being a user-friendly first approach to the IUIS classification [1]. These figures enable non-PID specialists to select the most appropriate diagnostic tree and to undertake some preliminary investigations, whilst contacting an expert in PIDs. They may also help in the selection of the center or expert to whom the patient should be referred, given the patient’s particular phenotype. In all cases, whether a tentative diagnosis can be made based on these figures or not, we recommend that the practitioner outside the field who sees a patient with a possible PID seeks specialist advice.

To simplify our figures, we did not systematically include all data from the IUIS classification (OMIM number, presumed pathogenesis, affected cells or function…) [1]. In order to present the 24 pages from the IUIS classification in only 8 figures, we used common abbreviations familiar to most physicians (explained in footnotes). The use of a color code makes these figures easy to follow, so that they could be hung, in larger format, in clinical wards. This is also suitable for informing young clinicians and students.

To make these figures easier to use by clinicians and biologists, we highlighted the clinical and biological features, adding to the data from the IUIS classification some other features typical of the PID in question. This allows an initial orientation towards a particular disease or group of diseases. Whenever it was possible, we have focused on clinical or routine laboratory features that distinguish disorders that are closely related. Example: A female infant with an opportunistic infection in whom lymphocyte subpopulation investigation reveals profound CD3 and CD16/56 lymphopenia without CD19/20 lymphopenia has a SCID T-B+NK- phenotype, which strongly suggests Jak3 deficiency (Fig. 1). After discussion with a team specialized in the diagnosis and treatment of SCID patients, an analysis of the JAK3 gene will be arranged as a priority, while expert advice will be given on the appropriate management for the infant.

Though atypical forms of PID are increasingly reported in the literature [12–15], typical presentations of these conditions remain predominant, permitting this classification to be useful in most of cases. Moreover, the genetic heterogeneity of most PIDs is high and patients with almost any PID may lack coding mutations in known disease-causing genes. This manuscript will therefore be up-dated every other year along with the IUIS classification. Meanwhile, we hope that this phenotypic approach to diagnosis of PID can constitute a useful tool for physicians or biologists from various related specialties, especially in the setting of pediatric and adult medicine (internal medicine, pulmonology, he-matology, oncology, immunology, infectious diseases, etc…) who may encounter the first presentation of PID patients.

Conclusion

The strengths of this algorithmic approach to the diagnosis of PID are its simplified format, reliance on phenotypic features, presentation in user-friendly pathways, and validation by a group of PID experts. We hope they will be useful to physicians at the bedside in several areas of pediatrics, internal medicine, and surgery. While these algorithms cannot be comprehensive, due to the tremendous genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of PIDs, they will be improved over time with progress in the field as well as by feed-back from users. They will also be expanded with the discovery of new PIDs and the refined description of known PIDs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Capucine Picard and Dr Claire Fieschi for their contribution to this work.

Abbreviations

- αFP

Alpha- fetoprotein

- Ab

Antibody

- AD

Autosomal dominant inheritance

- ADA

Adenosine deaminase

- Adp

Adenopathy

- AIHA

Auto-immune hemolytic anemia

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- Anti PSS

Anti- pneumococcus polysaccharide antibodies

- AR

Autosomal recessive inheritance

- BL

Blymphocyte

- CAPS

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes

- CBC

Complete blood count

- CD

Cluster of differentiation

- CGD

Chronic granulomatous disease

- CID

Combined immunodeficiency

- CINCA

Chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome

- FCM*

Flow cytometry available

- CMML

Chronic myelo-monocytic leukemia

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CVID

Common variable immunodeficiency disorders

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTL

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

- DA

Duration ofattacks

- Def

Deficiency

- DHR

DiHydroRhodamine

- Dip

Diphtheria

- EBV

Epstein-barr virus

- EDA

Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia

- EDA-ID

Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency

- EO

Eosinophils

- FA

Frequencyofattacks

- FCAS

Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- Hib

Haemophilus influenzae serotype b

- HIDS

Hyper IgD syndrome

- HIES

Hyper IgE syndrome

- HIGM

Hyper Ig M syndrome

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- HSM

Hepatosplenomegaly

- Hx

Medical history

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- IL

Interleukin

- LAD

Leukocyte adhesion deficiency

- MKD

Mevalonate kinase deficiency

- MSMD

Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacteria disease

- MWS

Muckle-Wells syndrome

- N

Normal, not low

- NK

Natural killer

- NKT

Natural killer Tcell

- NN

Neonate

- NOMID

Neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease

- NP

Neutropenia

- PAPA

Pyogenic sterile arthritis pyoderma gangrenosum, Acne syndrome

- PMN

Neutrophils

- PT

Platelet

- SCID

Severe combined immune deficiencies

- Sd

Syndrome

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- SPM

Splenomegaly

- Subcl

IgG subclass

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- Tet

Tetanus

- TL

Tlymphocyte

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- TRAPS

TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome

- WBC

White blood cells

- XL

X-linked

Contributor Information

Ahmed Aziz Bousfiha, Email: profbousfiha@gmail.com, Clinical Immunology Unit, A. Harouchi Children Hospital, Ibn Rochd Medical School, King Hassan II University, 60, rue 2, Quartier Miamar, Californie, Casablanca, Morocco.

Leïla Jeddane, Clinical Immunology Unit, A. Harouchi Children Hospital, Ibn Rochd Medical School, King Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco.

Fatima Ailal, Clinical Immunology Unit, A. Harouchi Children Hospital, Ibn Rochd Medical School, King Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco.

Waleed Al Herz, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, Kuwait City, Kuwait; Allergy and Clinical Immunology Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Al-Sabah Hospital, Kuwait City, Kuwait.

Mary Ellen Conley, Department of Pediatrics, University of Tennessee College of Medicine, Memphis, TN, USA; Department of Immunology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA.

Charlotte Cunningham-Rundles, Department of Medicine and Pediatrics, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA.

Amos Etzioni, Meyer’s Children Hospital– Technion, Haifa, Israel.

Alain Fischer, Pediatric Hematology- Immunology Unit, Hôpital Necker Enfants-Malades, Assistance Publique–Hôpital de Paris, Necker Medical School, Paris Descartes University, Paris, France.

Jose Luis Franco, Group of Primary Immunodeficiencies, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Raif S. Geha, Division of Immunology, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA, USA

Lennart Hammarström, Division of Clinical Immunology, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Karolinska Institute at Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden.

Shigeaki Nonoyama, Department of Pediatrics, National Defense Medical College, Saitama, Japan.

Hans D. Ochs, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, WA, USA

Chaim M. Roifman, Division of Immunology and Allergy, Department of Pediatrics, The Hospital for Sick Children and the University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Reinhard Seger, Division of Immunology, University Children’s Hospital, Zürich, Switzerland.

Mimi L. K. Tang, Department of Allergy and Immunology, Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Jennifer M. Puck, Department of Pediatrics, University of California San Francisco and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, San Francisco, CA, USA

Helen Chapel, Clinical Immunology Unit, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Luigi D. Notarangelo, Division of Immunology, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA, USA The Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA, USA.

Jean-Laurent Casanova, St. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA; Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Necker Branch, Necker Medical School, University Paris Descartes and INSERM U980, Paris, France.

References

- 1.Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova JL, Chapel H, Conley ME, Cunningham-Rundles C, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee for Primary Immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2011;2:54. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parvaneh N, Casanova JL, Notarangelo LD, Conley ME. Primary immunodeficiencies: a rapidly evolving story. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(2):314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ochs HD, Smith CIE, Puck JM. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: a molecular & cellular approach. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casanova JL, Abel L. Primary immunodeficiencies: a field in its infancy. Science. 2007;317:617–619. doi: 10.1126/science.1142963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Notarangelo LD, Casanova JL. Primary immunodeficiencies: increasing market share. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conley ME, Notarangelo LD, Casanova JL. Definition of primary immunodeficiency in 2011: a “trialogue” among friends. NY Acad Sci. 2011;1238:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bousfiha AA, Jeddane L, Ailal F, Benhsaien I, Mahlaoui N, Casanova JL, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases worldwide: more common than generally thought. J Clin Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9751-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vries E. European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) members. Patient-centred screening for primary immunodeficiency, a multi-stage diagnostic protocol designed for non-immunologists: 2011 update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167(1):108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira JB, Fleisher TA. Laboratory evaluation of primary immunodeficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:S297–S305. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Admou B, Haouach K, Ailal F, Benhsaien I, Barbouch MR, Bejaoui M, et al. Primary immunodeficiencies: diagnosis approach in emergent countries (African Society for Primary Immunodeficiencies) Immunol Biol Spec. 2010;25(5–6):257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samarghitean C, Ortutay C, Vihinen M. Systematic classification of primary immunodeficiencies based on clinical, pathological, and laboratory parameters. J Immunol. 2009;183(11):7569–7575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perreault S, Bernard G, Lortie A, Le Deist F, Decaluwe H. Ataxia-telangiectasia presenting with a novel immunodeficiency. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46(5):322–324. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohr J, Beutel K, Maul-Pavicic A, Vraetz T, Thiel J, Warnatz K, et al. Atypical familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to mutations in UNC13D and STXBP2 overlaps with primary immunodeficiency diseases. Haematologica. 2010;95(12):2080–2087. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.029389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pessach I, Walter J, Notarangelo LD. Recent advances in primary immunodeficiencies: identification of novel genetic defects and unanticipated phenotypes. Pediatr Res. 2009;65(5 Pt 2):3R–12. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819dbe1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villa A, Sobacchi C, Notarangelo LD, Bozzi F, Abinun M, Abrahamsen TG, et al. V(D)J recombination defects in lymphocytes due to RAG mutations: severe immunodeficiency with a spectrum of clinical presentations. Blood. 2001;97(1):81–88. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]