Abstract

Background

While several MRI parameters are used to assess tissue perfusion during hyperacute stroke, it is unclear which is optimal for measuring clinically-relevant reperfusion. We directly compared MTT prolongation (MTTp), TTP, and time-to-maximum (Tmax) to determine which best predicted neurological improvement and tissue salvage following early reperfusion.

Methods

Acute ischemic stroke patients underwent three MRI's: <4.5hr (tp1), at 6hr (tp2), and at 1 month after onset. Perfusion deficits at tp1 and tp2 were defined by MTTp, TTP, or Tmax beyond four commonly-used thresholds. Percent reperfusion (%Reperf) was calculated for each parameter and threshold. Regression analysis was used to fit %Reperf for each parameter and threshold as a predictor of neurological improvement [defined as admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) – 1 month NIHSS (ΔNIHSS)] after adjusting for baseline clinical variables. Volume of reperfusion, for each parameter and threshold, was correlated with tissue salvage, defined as tp1 perfusion deficit volume – final infarct volume.

Results

50 patients were scanned at 2.7 hours and 6.2 hours after stroke onset. %Reperf predicted ΔNIHSS for all MTTp thresholds, for Tmax > 6s and > 8s, but for no TTP thresholds. Tissue salvage significantly correlated with reperfusion for all MTTp thresholds and with Tmax > 6s, while there was no correlation with any TTP threshold. Among all parameters, reperfusion defined by MTTp was most strongly associated with ΔNIHSS (MTTp>3s, p=0.0002) and tissue salvage (MTTp> 3s and 4s, P<0.0001).

Conclusion

MTT-defined reperfusion was the best predictor of neurological improvement and tissue salvage in hyperacute ischemic stroke.

Introduction

MRI and CT have been extensively studied in acute ischemic stroke to identify early signatures which can delineate the ischemic penumbra--non-functioning, but viable tissue which can be salvaged with reperfusion.[1] Because of the reperfusion-dependence of tissue outcome in the ischemic penumbra, finding the ideal measure for perfusion and reperfusion is essential towards the goal of developing “penumbral imaging.” Calculating absolute CBF and CBV using bolus-tracking methods requires several assumptions which are prone to error when applied clinically.[2] Moreover, CBF and CBV values vary two to three fold between gray and white matter.[3] These limitations have led to the development of perfusion parameters based on the temporal characteristics of the intravascular contrast signal after intravenous injection. These “time-based” perfusion parameters have the advantage over CBF and CBV maps of being uniform across gray and white matter, allowing for easier visual detection of perfusion lesions and obviating the need for gray-white segmentation. While several parameters have been studied, the three most commonly used in stroke trials[4-6] are: (1) MTT defined as CBV/CBF, (2) TTP defined as the time from contrast arrival (of the arterial input function) to the time of maximal tissue concentration, and (3) time-to-maximum (Tmax), defined as time at which the maximum value of the residue function occurs after deconvolution.[2]

Effective tissue reperfusion (perfusion restoration sufficient to meet metabolic demand) is a critical determinant for salvage of the ischemic penumbra and subsequent clinical improvement when accomplished early after arterial occlusion.[1] With the advent of non-invasive, rapid methods to measure local perfusion using MR and CT, reperfusion has served as an imaging endpoint in recent stroke trials evaluating the efficacy of acute reperfusion therapies in patients with diffusion- or CT-perfusion mismatch.[4-6] While reperfusion, measured in a variety of ways, is associated with less infarct growth [7, 8] and improved clinical outcome after stroke,[8-10] it is not clear which perfusion parameter is optimal for detecting clinically-effective reperfusion as they have not been directly compared for prediction of neurological improvement and tissue salvage within a single study. Therefore, we investigated MTT, TTP, and Tmax to determine which reperfusion measurement was most strongly associated with neurological improvement (“clinically-relevant” reperfusion) and tissue salvage during acute ischemic stroke.

Methods

Patients and Inclusion Criteria

This study utilized data collected from a prospective observational MRI study in acute ischemic stroke patients at a large, urban, tertiary care referral center. After approval from the institutional review board, consecutive patients were enrolled within 4.5 hours of stroke onset based on the following pre-specified inclusion criteria: clinically-suspected acute cortical ischemic stroke; age ≥ 18 years; NIHSS ≥ 5; and patient or patient's next of kin capable of providing written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included bilateral strokes, infratentorial stroke, contraindication to MRI or MRI contrast, pregnancy, or any acute endovascular intervention. Both IV tPA-treated and untreated patients were included. The study imposed no delay in time-to-tPA treatment and no deviation from standard monitoring practices or standard inclusion/exclusion criteria for IV tPA administration. The NIHSS was collected prospectively by a stroke neurologist or research coordinator on admission, at all imaging time-points, and at one month follow-up. Clinical data including demographic data and past medical history were obtained by the coordinator prospectively at the time of patient enrollment.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Protocol

Patients underwent serial MRI scans within 4.5 hours (tp1), at 6 hours (tp2), and at 1 month after stroke onset, on a 3T Siemens whole body Trio scanner with a 12-channel head coil. For tPA-treated patients, tp1 was performed as soon as possible after IV tPA bolus (during tPA infusion). Because tissue fate depends on the history of perfusion change during the hyperacute phase of ischemia (while tissue may still be reversibly injured), we measured tissue reperfusion within the first six hours of onset to examine the correlation between reperfusion and clinical improvement. Six hours was chosen because reperfusion-based therapies administered within, but not beyond, this time-frame have demonstrated clinical efficacy.[11, 12]

The protocol included diffusion-weighted, FLAIR [TR/TE=10000/115ms; inversion time = 2500ms; matrix=512×416; 20 slices, slice thickness (TH)=5mm], and dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion images with 0.2ml/kg gadolinium injected at 5ml/sec (T2*-weighted gradient echo EPI sequence; TR/TE=1500/43ms; 14 slices, TH=5mm, zero interslice gap; matrix=128×128).

Image Post-Processing and Data Analysis

MTT, TTP, and Tmax maps were calculated for each patient at tp1 and tp2. Voxels within the middle cerebral artery (MCA) of the contralateral hemisphere were manually chosen and the mean concentration curve of these voxels was used as the arterial input function (AIF). Perfusion parameters were calculated according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where Ct(t)=relative contrast agent concentration in the tissue at time t, derived from the T2* relaxation rate change under the assumption of linearity; Ca(t)=the AIF; and R(t)=the unit impulse response of the residue function, a measure of the amount of tracer in the voxel at time t.[2] Convolution (represented by ⊗) is necessary to calculate the tissue concentration curve as the true AIF is temporally distributed, made up of multiple short impulses over time, rather than a single unit impulse function. TTP was calculated as the time from AIF contrast bolus arrival to the time of maximal Ct(t). Relative CBV was computed as the ratio of [the integral of tissue concentration curve, Ct(t)] / [the integral of the AIF curve, Ca(t)]. To minimize time lag effects of the AIF on perfusion measurements, a time-shift insensitive block-circulant singular value decomposition was utilized to deconvolve Eq. 1.[13] After deconvolution, CBF*R(t) was obtained. The time when the maximal concentration of the deconvolved tissue curve [CBF*R(t)] occurs is Tmax and the height of the curve at this maximal concentration was used to measure relative CBF. MTT was calculated as: [CBV/CBF]. Six parameter rigid registration aligned all images across time-points for each patient using FSL 3.2 (FMRIB, Oxford, UK).[14]

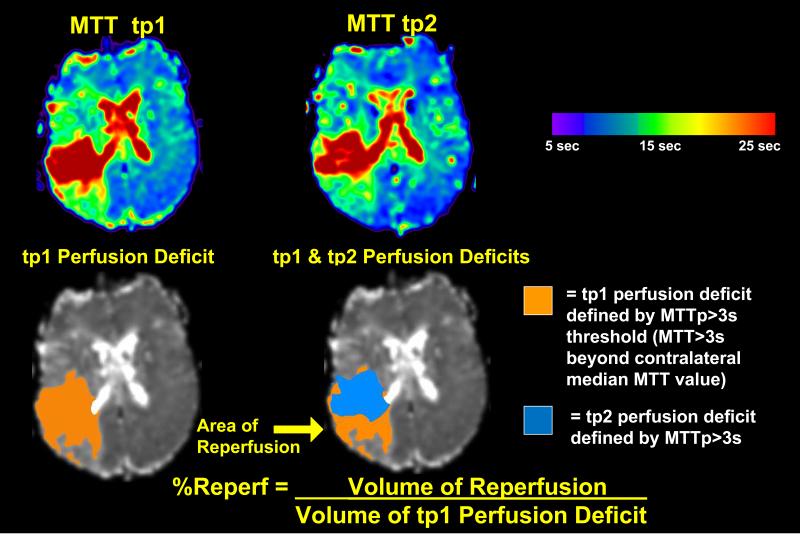

The “perfusion deficit” for each voxel within the ischemic hemisphere was evaluated using MTT prolongation (MTTp), TTP, and Tmax. MTTp for each voxel was defined as [MTT within each voxel of the ischemic hemisphere]–[median MTT of contralateral hemisphere], whereas TTP and Tmax were absolute measures. Based on previous studies, four commonly-used thresholds of “perfusion deficits” were chosen to test a range of varying perfusion deficit severities.[15-17] For MTTp, thresholds of 3, 4, 5, and 6 seconds (s) were tested. For TTP and Tmax, thresholds of 2, 4, 6, and 8s were tested. The “volume of reperfusion” (Vreperf) was defined as the volume of voxels with perfusion deficit at tp1, but no perfusion deficit at tp2. The “percent reperfusion” (%Reperf) was defined as [volume of reperfusion] / [volume of tp1 perfusion deficit] (Figure 1). The “volume of non-reperfusion” (Vnon-reperf) was defined as the volume of voxels with perfusion deficit at both tp1 and tp2. “Tissue salvage” was defined as: [tp1 perfusion deficit volume]–[1 month infarct volume]. For infarct delineation, hyperintense lesions were manually outlined on the 1 month FLAIR image by a stroke neurologist (A.L.F.). The study team members calculating the perfusion maps were blinded to all clinical data. Isolated regions of abnormal perfusion <1 ml were removed from analyses to minimize inclusion of noise-induced variations.

Figure 1. Calculation of Reperfusion.

MTTp, TTP, and Tmax perfusion deficits were calculated for tp1 and tp2. The “volume of reperfusion” was defined as: the volume of voxels with perfusion deficit at tp1, but no perfusion deficit at tp2. The “percent reperfusion” (%Reperf) was defined as [volume of reperfusion] / [volume of tp1 perfusion deficit]. In the upper panel, example perfusion maps (for MTT) at tp1 and tp2 are shown: warm colors represent maximal hypoperfusion, while cool colors represent normal perfusion (color bar). In the lower panel, the orange mask delineates the tp1 perfusion deficit defined by MTT >3s longer than the median MTT of the contralateral hemisphere (MTTp >3s threshold). The blue mask delineates the tp2 perfusion deficit at MTTp >3s. At tp2, the perfusion deficit shrinks and the non-overlapped region (yellow arrow) indicates the region of reperfusion.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 and Graphpad Prism 5. P-value<0.05 was required for significance. A variable-selection method evaluated which reperfusion measurement (MTTp, TTP, or Tmax) and which threshold best predicted neurological improvement while adjusting for three baseline clinical variables. Neurological improvement was defined as admission NIHSS–1 month NIHSS (ΔNIHSS), such that a positive ΔNIHSS indicates improvement. Specifically, 12 linear regression models (3 parameters, 4 thresholds) were used to fit %Reperf as a predictor of neurological improvement while adjusting for age, admission NIHSS, and tPA treatment status. The latter clinical variables were chosen based on an exploratory univariate analysis requiring a p-value < 0.2 for entry into the model. Age and baseline NIHSS met this criteria, while the other patient characteristics listed in Table 1 did not. In addition to age and baseline NIHSS, tPA treatment status was added to each model due to its known effect on clinical outcome after stroke. [18, 19] The latter three variables were entered into all 12 regression models. Regression diagnostics evaluated distributional assumptions of the residuals and functional form of the covariates.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| N=50 | |

|---|---|

| Female† | 18 (35%) |

| Age, years* | 65 [57,74] |

| Admission NIHSS* | 16 [8,20] |

| African-American† | 19 (37%) |

| tPA treatment† | 38 (74%) |

| Admission Mean Arterial Pressure, mmHg* | 113 [104,129] |

| Admission Glucose, mg/dl* | 124 [106,148] |

| Time to tp1, hour* | 2.7 [2.1,3.5] |

| Time to tp2, hour* | 6.2 [6.1,6.5] |

| Medical History | |

| Hypertension† | 38 (74%) |

| Diabetes† | 17 (33%) |

| Congestive Heart Failure† | 6 (12%) |

| Tobacco Use† | 12 (24%) |

| Coronary Artery Disease† | 14 (28%) |

| Stroke or TIA† | 8 (16%) |

Median [interquartile range];

n (%)

To measure the effect of reperfusion on tissue fate, Vreperf for each parameter/threshold was correlated with tissue salvage using Spearman rank correlation (ρ).

Differences in Vreperf, Vnon-reperf, and %Reperf between MTTp vs. Tmax and MTTp vs. TTP were compared using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. The overlap (similarity index, SI) between two parameters was assessed using the Dice coefficient, computed as 2*|A⋂B| / (|A|+|B|), where A and B are regions of tp1 perfusion deficit, reperfusion, or non-reperfusion from the two MR parameters being compared. SI ranged from 0 and 1 corresponding to no and perfect overlap, respectively.

Results

A total of 63 acute ischemic stroke patients were prospectively scanned. Five patients did not go on to receive tp2 due to intolerance of tp1 scan due to claustrophobia, poor contrast delivery on the perfusion weighted imaging, or medical instability, leaving 58 patients who received the tp2 scan. An additional eight patients who received both tp1 and tp2 scans were excluded from the analysis due to motion artifact or poor perfusion studies limiting ability to process the perfusion images. This left 50 patients total for the primary analysis. An additional ten patients did not complete the one month scan due to death or loss to follow-up, leaving a total of 40 patients for analyses including the final infarct. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

MTT-defined reperfusion best predicted neurological improvement at one month

%Reperf was significantly associated with ΔNIHSS for all MTTp thresholds with the strongest association for the MTTp>3s threshold (P=0.0002). %Reperf was significantly associated with ΔNIHSS for two Tmax thresholds: 6s (P=0.037) and 8s (P=0.009). %Reperf was not associated with ΔNIHSS for any TTP threshold (Table 2).

Table 2.

Neurological Improvement and Percent Reperfusion†

| Parameter / Threshold | β(SE)§ | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|

| MTTp >3s | 0.114 (0.039) | 0.0002 |

| MTTp >4s | 0.108 (0.028) | 0.0004 |

| MTTp >5s | 0.103 (0.027) | 0.001 |

| MTTp >6s | 0.097 (0.027) | 0.001 |

| TTP >2s | 0.054 (0.047) | 0.14 |

| TTP >4s | 0.036 (0.051) | 0.18 |

| TTP >6s | 0.015 (0.050) | 0.052 |

| TTP >8s | 0.011 (0.047) | 0.056 |

| Tmax >2s | 0.079 (0.048) | 0.12 |

| Tmax >4s | 0.063 (0.036) | 0.070 |

| Tmax >6s | 0.079 (0.036) | 0.037 |

| Tmax >8s | 0.074 (0.034) | 0.009 |

ΔNIHSS=Admission NIHSS-1month NIHSS;

The predictor of interest (%Reperf) was adjusted for age, admission NIHSS, and tPA treatment.

β(SE)=Regression coefficient (standard error)

P<0.05 for statistical significance.

MTT-defined reperfusion best correlated with tissue salvage at 1 month

We then examined which reperfusion parameter/threshold correlated with tissue salvage. Reperfusion measured by MTTp significantly correlated with tissue salvage across all MTTp thresholds (strongest was for MTTp>3s and >4s; ρ=0.576, P<0.0001 and ρ =0.555, P<0.0001, respectively) and for one Tmax threshold, (Tmax>6s: ρ=0.321, P=0.038), but did not correlate with tissue salvage for any TTP threshold (Table 3).

Table 3.

| Parameter/Threshold | ρ § | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|

| MTTp >3s | 0.576 | <0.0001 |

| MTTp >4s | 0.555 | <0.0001 |

| MTTp >5s | 0.457 | 0.002 |

| MTTp >6s | 0.414 | 0.006 |

| TTP >2s | 0.150 | 0.18 |

| TTP >4s | 0.292 | 0.34 |

| TTP >6s | 0.288 | 0.060 |

| TTP >8s | 0.055 | 0.72 |

| Tmax >2s | 0.149 | 0.35 |

| Tmax >4s | 0.266 | 0.089 |

| Tmax >6s | 0.321 | 0.038 |

| Tmax >8s | 0.209 | 0.18 |

Vreperf=[volume of voxels which had a perfusion deficit at tp1 and no perfusion deficit at tp2].

Tissue salvage=[volume of tp1 perfusion deficit]-[1 month infarct volume].

Spearman's Correlation Coefficient

P<0.05 for statistical significance.

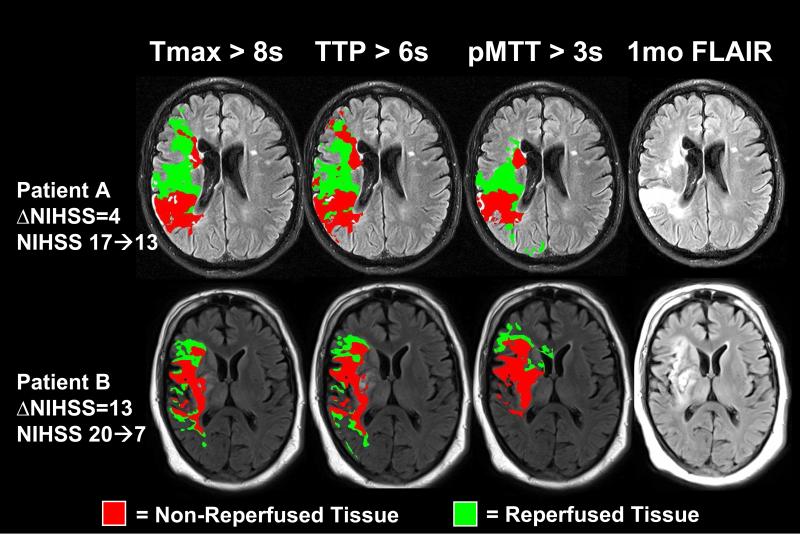

Reperfused tissue measured by MTTp vs. Tmax and TTP demonstrated low spatial overlap

For a closer look at the differences between the best-performing thresholds from each parameter, Vreperf, Vnon-reperf, and %Reperf were compared for Tmax and TTP as compared to MTTp. Vreperf and Vnon-reperf was higher for MTTp than Tmax. Vreperf was higher for MTTp than TTP (Table 4). We then assessed spatial overlap across the three parameters for regions of tp1 perfusion deficit, reperfusion, and non-reperfusion across all subjects. Overlap for the regions of reperfusion between MTTp and Tmax or TTP were low at 0.35 and 0.34, respectively (Table 4). To visualize how perfusion changes for a given parameter/threshold correlated with eventual tissue fate, masks of reperfused and non-reperfused tissue for MTTp>3s, Tmax>8s, and TTP>6s were overlaid onto the 1 month FLAIR for two example patients, showing better agreement for MTTp with the final infarct region (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Volume of Reperfusion, Volume of Non-Reperfusion, Percent Reperfusion, and Similarity Index comparing MTTp to Tmax and TTP

| MTTp>3s | Tmax>8s | TTP>6s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vreperf, m1† | 18.8 [9.9, 36.8] | 13.5 [3.3, 26.5]** | 16.0 [6.1, 26.3]* |

| Vnon-reperf, m1† | 41.2 [22.2, 79.2] | 27.0 [8.1, 64.6]*** | 33.2 [15.8, 65.3] |

| %Reperf† | 32.5 [11.6, 48.4] | 33.8 [11.9, 56.8] | 29.8 [14.9, 43.0] |

| SI§ for tp1 perfusion deficit | 0.57 [0.46 ,0.73] | 0.58, [0.42, 0.72] | |

| SI§ for region of reperfusion | 0.35 [0.21, 0.42] | 0.34 [0.22, 0.47] | |

| SI§ for region of non-reperfusion | 0.63 [0.37, 0.72] | 0.49 [0.31, 0.72] |

Median [interquartile range]

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.0001; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test vs. MTTp>3s.

Similarity Index (SI) was computed as 2*|A∩B| / (|A|+|B|) (Dice coefficient), where A and B are regions of overlap for MTTp>3s vs. Tmax>8s and MTTp>3s vs. TTP>6s; SI ranges from 0 to 1, corresponding to no and perfect agreement, respectively.

Figure 2. Comparison of MTT, Tmax, and TTP in Two Example Patients.

Shown are two patient examples of (A) right MCA stroke in a 55 year old man with limited neurological improvement by 1 month (ΔNIHSS =4) and (B) right MCA stroke in a 54 year old man with significant neurological improvement by 1 month (ΔNIHSS=13). Reperfused (green) and non-reperfused (red) tissue for MTTp >3s and Tmax >6s were overlaid on the final infarct at 1 month. Perfusion changes for MTTp >3s more closely approximated the final infarct and surrounding non-infarct regions on 1 month FLAIR relative to Tmax >8s or TTP >6s which overestimate the tissue at risk.

Discussion

In this prospective observational imaging study of serial MRIs measuring early reperfusion as a critical determinant of tissue salvage, MTTp-defined reperfusion >3s was the parameter/threshold most strongly associated with neurological improvement. Weaker associations were observed for MTTp>4, 5, and 6s and for Tmax>6 and 8s. Tissue salvage was associated with all MTTp thresholds and Tmax>6s while no significant association was found with the remaining Tmax thresholds or any TTP threshold. Indeed, we found that the volumes of reperfusion differed within patients for the optimal MTTp, Tmax, and TTP thresholds. Moreover, there was little overlap for the regions of reperfusion between MTTp and Tmax or TTP (Table 4, Figure 2).

Early reperfusion predicts neurological improvement during acute stroke[7-10] and often serves as an imaging endpoint in clinical trials of acute therapies.[4, 6, 20] Therefore, knowing which reperfusion measurement most closely reflects neurological improvement would guide future trial design. In a meta-analysis of clinical trials using diffusion-perfusion mismatch to select patients for thrombolytic treatment, reperfusion was associated with an odds ratio of 5.2 for improved clinical outcome as measured by 3 month modified Rankin scale.[10] Thus far, however, studies have not determined which definition of reperfusion is most closely tied to neurological improvement after stroke.

Numerous studies have attempted to identify the optimal parameter and threshold measuring the baseline perfusion deficit as a predictor of final tissue fate and/or clinical outcome, but have had conflicting results. [15, 16, 21-23] Few studies have considered reperfusion status when searching for the optimal parameter or threshold.[23, 24] In the Diffusion and Perfusion Imaging Evaluation for Understanding Stroke Evolution (DEFUSE) trial, which measured perfusion using Tmax, penumbral salvage (defined as baseline perfusion deficit volume-final infarct volume) correlated with infarct growth for Tmax >6s compared to other thresholds.[24] In patients without reperfusion, Tmax >4s was a more accurate predictor of final infarct than Tmax >2s.

It is likely that both the quantitative degree of reperfusion as well as the timing of reperfusion contribute to the ability of reperfusion to accurately predict neurological improvement. Studies using dual-imaging paradigms to assess reperfusion have typically defined reperfusion as an “all or none” event. For example, in DEFUSE, stroke subjects were defined as “reperfused” if the volume of reperfusion was >30% (imaged at 6-9 hours after stroke onset).[25] In the Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolytic Evaluation Trial (EPITHET), subjects were defined as “reperfused” if the volume of reperfusion was >90% (imaged at 3-5 days after onset).[4] More quantitative tissue-based reperfusion with a continuous range of reperfusion may predict outcomes more precisely. Vessel recanalization is another potential marker of early improvement and is associated with good outcome and reduced mortality;[26] however, recanalization does not always lead to reperfusion at the tissue level, and the lack of recanalization does not always translate to non-reperfusion, given the presence collateral flow.[27]

While MTTp-defined reperfusion performed optimally in predicting neurological improvement (Table 2) and more closely approximated the final infarct than Tmax or TTP (Table 3, Figure 2), this study was not designed to answer why MTTp performed better. Clinical and in silico studies provide potential explanations for the short-comings of TTP and Tmax relative to MTT. While MTT is thought to reflect tissue perfusion at the microvascular level (defined as CBV/CBF), TTP and Tmax, are largely affected by contrast “delay” from indirect macrovascular pathways of contrast delivery (i.e. collateral flow). Calculation of TTP and Tmax includes the time between arrival of contrast at the contralateral MCA and contrast delivery to the tissue, a delay which may be particularly significant in the setting of arterial stenosis or occlusion proximal to the tissue of interest.[28] Simulations suggest that TTP and Tmax are influenced by contrast arrival delay and may also be affected by dispersion, but to a much lesser degree.[29] It is possible that tissue may demonstrate abnormal TTP or Tmax due to delay despite adequate and normal perfusion. Therefore, MTTp may be a more accurate marker of perfusion changes relative to other time-based perfusion parameters. A relative decrease in sensitivity to voxel-wise perfusion changes by Tmax may explain why Tmax-measured reperfusion did not correlate with neurological improvement and tissue salvage at the same threshold.

The study has several limitations. Data was obtained from a single institution. We required that patients have an NIHSS ≥ 5 to be included; therefore, this cohort included strokes of greater severity than average stroke patients. Thus, our results may not apply to patients with low stroke severity. Reperfusion was specifically measured within 6 hours; therefore, our associations may not be valid outside this time window. The majority of patients received IV tPA which may bias the results towards any unique effects of tPA beyond reperfusion; therefore, tPA was included as a covariate. However, the mechanism by which reperfusion occurred (either spontaneous or via tPA) should not impact our conclusions regarding the relationship between reperfusion and neurological improvement or tissue salvage. NIHSS improvement as an endpoint may introduce some heterogeneity as the NIHSS is not equally represented throughout the brain, however we chose ΔNIHSS in order to capture improvement from reperfusion and tissue salvage rather than disability scales which may be influenced by clinical course, co-morbidities, and recovery mechanisms. While this study focused on common time-based perfusion parameters and specific thresholds of these parameters used in recent clinical trials, there are several additional parameters, such as CBF and CBV which are also useful in predicting neurological improvement and tissue salvage which were not evaluated in this study. Furthermore, there are other factors besides early reperfusion which affect neurological improvement and tissue salvage, such as intrinsic tissue vulnerability, which were not accounted for in the present study.

Conclusion

MTT may be the best time-based perfusion parameter to define clinically-relevant reperfusion after stroke and may be considered in future studies when reperfusion is used as a radiological biomarker in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

None

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health NIH 5P50NS055977 (to JML) and K23 NS069807 (to AF) and from the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Requirements Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any financial relationships with the National Institutes of Health who funded this research.

John Smith declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Andria L. Ford, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Hongyu An, DSc declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Linglong Kong, PhD declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Hongtu Zhu, PhD declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Katie D. Vo, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

William J. Powers, MD declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Weili Lin, PhD declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Jin-Moo Lee, MD, PhD declares that he has no conflict of interest.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

References

- 1.Astrup J, Siesjo BK, Symon L. Thresholds in cerebral ischemia - the ischemic penumbra. Stroke. 1981;12(6):723–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.12.6.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostergaard L. Principles of cerebral perfusion imaging by bolus tracking. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22(6):710–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostergaard L, et al. High resolution measurement of cerebral blood flow using intravascular tracer bolus passages. Part II: Experimental comparison and preliminary results. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(5):726–36. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis SM, et al. Effects of alteplase beyond 3 h after stroke in the Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolytic Evaluation Trial (EPITHET): a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):299–309. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hacke W, et al. Intravenous desmoteplase in patients with acute ischaemic stroke selected by MRI perfusion-diffusion weighted imaging or perfusion CT (DIAS-2): a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):141–50. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70267-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons M, et al. A randomized trial of tenecteplase versus alteplase for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1099–107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butcher KS, et al. Refining the perfusion-diffusion mismatch hypothesis. Stroke. 2005;36(6):1153–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000166181.86928.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schellinger PD, et al. Stroke magnetic resonance imaging within 6 hours after onset of hyperacute cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(4):460–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalela JA, et al. Early magnetic resonance imaging findings in patients receiving tissue plasminogen activator predict outcome: Insights into the pathophysiology of acute stroke in the thrombolysis era. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(1):105–12. doi: 10.1002/ana.10781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra NK, et al. Mismatch-based delayed thrombolysis: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2011;41(1):e25–33. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.566869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furlan A, et al. Intra-arterial prourokinase for acute ischemic stroke. The PROACT II study: a randomized controlled trial. Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism. Jama. 1999;282(21):2003–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khatri P, et al. Good clinical outcome after ischemic stroke with successful revascularization is time-dependent. Neurology. 2009;73(13):1066–72. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b9c847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu O, et al. Tracer arrival timing-insensitive technique for estimating flow in MR perfusion-weighted imaging using singular value decomposition with a block-circulant deconvolution matrix. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(1):164–74. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143–56. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih LC, et al. Perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging thresholds identifying core, irreversibly infarcted tissue. Stroke. 2003;34(6):1425–30. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000072998.70087.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobesky J, et al. Which time-to-peak threshold best identifies penumbral flow? A comparison of perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35(12):2843–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147043.29399.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah MK, et al. Quantitative cerebral MR perfusion imaging: preliminary results in stroke. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32(4):796–802. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Counsell C, et al. Predicting outcome after acute and subacute stroke: development and validation of new prognostic models. Stroke. 2002;33(4):1041–7. doi: 10.1161/hs0402.105909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams HP, Jr., et al. Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology. 1999;53(1):126–31. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hacke W, et al. The Desmoteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke Trial (DIAS): a phase II MRI-based 9-hour window acute stroke thrombolysis trial with intravenous desmoteplase. Stroke. 2005;36(1):66–73. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149938.08731.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kane I, et al. Comparison of 10 different magnetic resonance perfusion imaging processing methods in acute ischemic stroke: effect on lesion size, proportion of patients with diffusion/perfusion mismatch, clinical scores, and radiologic outcomes. Stroke. 2007;38(12):3158–64. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.483842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaro-Weber O, et al. Maps of time to maximum and time to peak for mismatch definition in clinical stroke studies validated with positron emission tomography. Stroke. 2010;41(12):2817–21. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.594432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galinovic I, et al. Search for a map and threshold in perfusion MRI to accurately predict tissue fate: a protocol for assessing lesion growth in patients with persistent vessel occlusion. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(2):186–93. doi: 10.1159/000328663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivot JM, et al. Optimal Tmax threshold for predicting penumbral tissue in acute stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(2):469–75. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albers GW, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging profiles predict clinical response to early reperfusion: the diffusion and perfusion imaging evaluation for understanding stroke evolution (DEFUSE) study. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(5):508–17. doi: 10.1002/ana.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rha JH, Saver JL. The impact of recanalization on ischemic stroke outcome: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2007;38(3):967–73. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258112.14918.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soares BP, et al. Reperfusion is a more accurate predictor of follow-up infarct volume than recanalization: a proof of concept using CT in acute ischemic stroke patients. Stroke. 2010;41(1):e34–40. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.568766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada K, et al. Magnetic resonance perfusion-weighted imaging of acute cerebral infarction: effect of the calculation methods and underlying vasculopathy. Stroke. 2002;33(1):87–94. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calamante F, et al. The physiological significance of the time-to-maximum (Tmax) parameter in perfusion MRI. Stroke. 2010;41(6):1169–74. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.580670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]