Abstract

Autoreactive B lymphocytes are essential for the development of T cell–mediated type 1 diabetes (T1D). Cytoplasmic Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a key component of B cell signaling, and its deletion in T1D-prone NOD mice significantly reduces diabetes. However, the role of BTK in the survival and function of autoreactive B cells is not clear. To evaluate the contributions of BTK, we used mice in which B cells express an anti-insulin BCR (125Tg) and promote T1D, despite being anergic. Crossing Btk deficiency onto 125Tg mice reveals that, in contrast to immature B cells, mature anti-insulin B cells are exquisitely dependent upon BTK, because their numbers are reduced by 95%. BTK kinase domain inhibition reproduces this effect in mature anti-insulin B cells, with less impact at transitional stages. The increased dependence of anti-insulin B cells on BTK became particularly evident in an Igκ locus site–directed model, in which 50% of B cells edit their BCRs to noninsulin specificities; Btk deficiency preferentially depletes insulin binders from the follicular and marginal zone B cell subsets. The persistent few Btk-deficient anti-insulin B cells remain competent to internalize Ag and invade pancreatic islets. As such, loss of BTK does not significantly reduce diabetes incidence in 125Tg/NOD mice as it does in NOD mice with a normal B cell repertoire. Thus, BTK targeting may not impair autoreactive anti-insulin B cell function, yet it may provide protection in an endogenous repertoire by decreasing the relative availability of mature autoreactive B cells.

Tolerant, or anergic, autoreactive-prone B cells make up a significant portion of the normal repertoire and may be increased in autoimmune disease states (1–4). Although the tolerant state of these cells is thought to provide protection from autoimmunity, there is evidence that they can be pathogenic. B cells expressing transgenic BCR specific for insulin (125Tg) have an anergic phenotype, characterized by lack of calcium signaling upon engagement with their Ag, loss of proliferative response to B cell mitogens, and failure to produce Ab in response to T-dependent immunization (5, 6). Nevertheless, these tolerant B cells can present Ag to T cells and promote development of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in the NOD mouse background (7, 8). In this model, the BCR affinity for insulin is moderate (Kd = 10−7 M) (9); the small, soluble Ag does not strongly cross-link the BCR; and the cells develop normally to fill all mature splenic subset niches (6), allowing study of a population that may mimic tolerant autoreactive cells in a natural repertoire.

B cell signaling governs all aspects of B cell development and response (10). Tonic signals through the BCR are necessary for normal development and survival (11). Ag binding of the BCR governs selection in the bone marrow, as well as mature B cell activation (12). Anergic B cells are exposed to their Ag in vivo and exist in a state in which signaling is impaired, illustrated by their loss of calcium flux and proliferation in response to Ag and their loss of Ab production in response to immunization. Understanding how signaling responses differ in these cells may provide interventional targets for treatment and prevention of autoimmunity.

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a component of the signaling cascade that propagates signals from the BCR (13, 14). This cytosolic Tec kinase is activated when BCR signaling promotes its recruitment to the cell membrane via PI3K-mediated actions and subsequent phosphorylation by SYK. Activated BTK phosphorylates PLCγ2, with downstream production of IP3 and diacyl glycerol, resulting in calcium flux and activation of transcription factors NF-κB and NFAT (15–20). BTK protein levels affect signaling responses; a reduction in the amount of available BTK was shown to blunt autoimmunity induced by Lyn deficiency, whereas overexpression induces a lupus-like syndrome (10, 21, 22). Because BTK inhibitors are in development for clinical use (23–26), understanding the role of this protein in the development, survival, and function of mature autoreactive cells relative to nonautoreactive cells may be useful for optimizing therapeutic strategies.

We showed previously that Btk deficiency in NOD mice protects against T1D (27), a T cell–mediated disease in which B lymphocytes are essential APCs (8, 28–30). Interestingly, anti-insulin Abs are lost in Btk-deficient NOD mice, whereas total serum IgG is unchanged, suggesting that selective elimination of autoreactive B cells may be responsible for the disease protection observed (27). Introduction of an anti-insulin H chain BCR transgene (VH125Tg), paired with endogenous L chains, revealed a role for BTK in the production or survival of anti-insulin B cells, because VH125Tg/Btk−/−/NOD mice have only half as many insulin-specific B cells as do their Btk-sufficient counterparts (27). However, these are small populations of cells whose functional status is unknown.

To explore the role of BTK in tolerant, autoreactive B cells, the 125Tg/NOD model (VH+Vκ) was used to provide a uniform, well-studied population of anergic anti-insulin B cells. The findings show that anergic, anti-insulin B cells depend more heavily upon BTK than do their nonautoreactive counterparts, having <10% of the normal numbers of B cells, and that this effect is specific to mature follicular and marginal zone subsets. Use of a BTK kinase inhibitor, ibrutinib, demonstrates the dependence of mature anti-insulin B cells on the kinase function of BTK. Surviving Btk-deficient anti-insulin B cells retain their ability to internalize Ag, traffic to inflamed islets, and promote disease, although at a somewhat delayed rate. These findings suggest that protective effects in the setting of a wild-type (WT) repertoire are likely to be due to a reduction in the numbers of available autoreactive cells rather than impairment of pathogenic function.

Materials and Methods

Animals and disease studies

125Tg/NOD mice, generated as previously described (5, 7), were crossed with Btk-deficient NOD mice, also generated as previously described (27), to produce 125Tg/NOD Btk−/− mice, which were backcrossed onto the NOD strain for ≥10 generations. Female mice were monitored for blood glucose levels weekly and considered diabetic at the first of two consecutive readings > 200 mg/dl.

Anti-insulin Vκ125 was targeted to the Igκ locus to generate Vκ125SDNeo mice (a kind gift from James W. Thomas, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) as follows. DNA encoding Vκ125/Jκ5 in the pSVG-125Vκ vector, originally used to generate Vκ125Tg mice (5), was amplified and cloned into the pVKR3-83-2Neo targeting vector (kindly provided by Roberta Pelanda, University of Colorado, Denver, CO) (31). The new pVKR-Vκ125SDNeo targeting construct was verified through sequencing. The pVKR-Vκ125SDNeo targeting vector was electroporated into mouse TL1 embryonic stem (ES) cells (129 strain), and ES cell clones were selected with 200 μg/ml G418 and 2 μM ganciclovir. Double-resistant colony DNA was SacI digested, and the targeted allele was identified by Southern blot using the 1.6-kb EcoRI probe (kindly provided by Roberta Pelanda) (31). Two clones were injected into blastocysts that were transplanted into pseudopregnant females. ES cell electroporation, selection, expansion, DNA isolation and digestion for initial Southern blot screening, and injection of ES cells into blastocysts were performed by the Vanderbilt Transgenic Mouse/Embryonic Stem Cell Shared Resource.

Chimeric male offspring were intercrossed with C57BL/6 females, and progeny were screened through PCR (using the following primers: forward 5′-TCTGCAAATGTCTGATGAGT-3′ and reverse 5′-CTCGTGCTTTACGG-TATCGC-3′) and Southern blot analysis, as above, to confirm the presence of the targeted allele. PCR also was used to confirm that the intact Vκ125/Jκ5 was present in targeted mice (forward 5′−AATGGATTTTCAGGTGCAGAT-3′ and reverse 5′−GCTCCAGCTTGGTCCCAGCA-3′). Six chimeric founder males were backcrossed to WT C57BL/6 females to generate mice carrying the targeted Vκ125SDNeo allele. The six independent lines of progeny were all found to contain the targeted allele, based on PCR and Southern blot analysis. Vκ125SDNeo mice were intercrossed with VH125Tg C57BL/6 females [Cg-Tg (Igh-6/Igh-V125)2Jwt/JwtJ] to generate VH125/Vκ125SDNeo offspring. Progeny from all six founder lines exhibited similar percentages of “edited” noninsulin-binding B cells, as assessed by flow cytometry, which remained consistent at various stages of backcrossing. One line was subsequently used for continued backcrossing to C57BL/6 and NOD mice and in experiments shown. VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo mice were intercrossed with Btk−/− mice to generate VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo Btk-sufficient mice and VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo Btk-deficient mice that were backcrossed onto the NOD strain for at least seven generations. All mice were housed under specific pathogen–free conditions, and all studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University.

BTK inhibitor treatment

125Tg/NOD mice were fed Ibrutinib (PCI-32765; Pharmacyclics [Sunnyvale, CA]; 0.24 g Ibrutinib/kg chow) or placebo chow ad libitum for 5–10 wk. All formulations were provided as a kind gift from Pharmacyclics. An average of 38 mg/kg Ibrutinib inhibitor was consumed per day, based on food weight consumed throughout the duration of the study and the number of mice/cage. This is above the dosage that ensures 99% inhibitor activity (24 mg/kg/d; personal communication, Pharmacyclics). B cell subsets were assessed by flow cytometry in freshly isolated organs, as outlined below.

Cell isolation, flow cytometry, and Abs

Bone marrow was eluted from long bones, and spleens and draining pancreatic lymph nodes were macerated with HBSS (Invitrogen) plus 10% FBS (HyClone). RBCs were lysed using Tris-NH4Cl. Freshly isolated pancreata were digested with 3 ml 1 mg/ml collagenase P diluted in HBSS for 30 min at 37°C, and tissue was disrupted using an 18-gauge needle. Ice-cold HBSS plus 10% FBS was added immediately to inhibit collagenase activity. Cells were directly analyzed by flow cytometry. Flow cytometry Ab reagents were reactive with B220 (6B2), IgMa (DS-1), CD19 (1D3), CD21 (7G6), CD23 (B3B4), CD93 (AA4.1) (BD Biosciences), or IgM (μ-chain specific) (Life Technologies). Biotin N-hydroxysuccinimide ester was used to biotinylate human insulin (both from Sigma) at pH 8 in bicine buffer. Streptavidin reagents (BD Biosciences) were used to detect biotinylated reagents. 7-Aminoactinomycin D (BD Biosciences) was used to exclude dead cells. Sample acquisition was performed using an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and FlowJo software (TreeStar) was used for analysis.

Ca2+-mobilization assay

Bone marrow cells were harvested and grown in bone marrow culture media with 15 ng/ml recombinant human IL-7 (PeproTech) for 5 d and then with no IL-7 for an additional 2 d to promote differentiation, as previously described (32). Intracellular Ca2+ mobilization was measured by determining changes in the ratio of bound/free fura 2-AM fluorescence intensities using a FlexStation II fluorometer (Molecular Devices), as previously described (32). Basal readings were taken for 45 s prior to stimulation. Cells were stimulated with 1 μg/ml anti-IgM [F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse μ-chain; Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs], and well fluorescence was monitored at 37°C.

In vivo labeling of sinusoidal bone marrow B cells

As described previously (33), lateral tail veins of mice were injected with 1 μg CD19-PE (BD Pharmingen) in 200 μl sterile 1× PBS. Mice were sacrificed after 2 min, and bone marrow was immediately eluted from femurs. Cells were isolated, as described above, and subsequently incubated with the indicated Abs to stain cell surface markers, together with CD19-allophycocyanin to help delineate all CD19+ cells, including sinusoidal B cells preferentially labeled with CD19-PE.

BCR-internalization assay

Ag internalization was performed as previously described (8). Briefly, freshly isolated bone marrow and spleen cells were incubated with biotinylated insulin for 30 min on ice to occupy BCR. After washing away excess biotinylated insulin, cells were incubated in complete media at 37°C for 0–10 min, at which point cells were stained with streptavidin-fluorochrome, as well as other indicated Abs. The relative surface level of biotinylated insulin or IgM was determined by dividing the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) at each time point by the MFI at t = 0, such that 100% represents no change in surface expression.

Results

Anergic, autoreactive B cells depend upon BTK

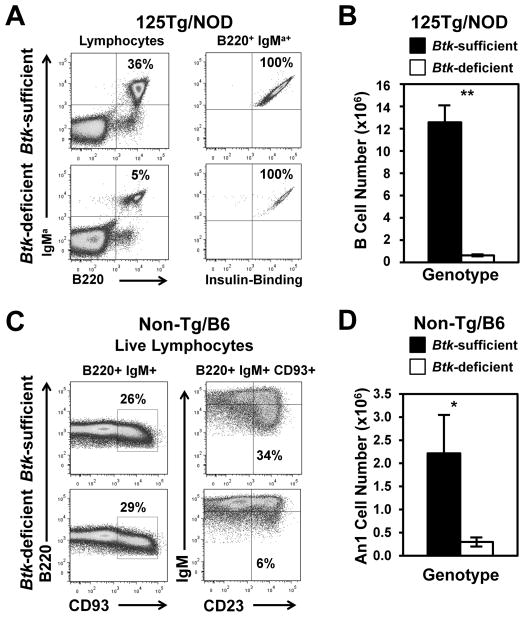

Btk deficiency was crossed onto 125Tg mice, on both C57BL/6 and NOD backgrounds. Fig. 1A shows representative flow cytometry dot plots from Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice versus their Btk-sufficient counterparts (summarized in Table I). Btk-deficient 125Tg mice had severely reduced spleen B cell compartments (0.63 ± 0.10 × 106 versus 12.6 ± 1.5 × 106 cells, p < 0.001), retaining only 5% of the normal numbers of insulin-binding B cells (Fig. 1B, Table II). Results for C57BL/6 mice do not differ from those for NOD mice (data not shown). To extend these findings to anergic B cells in a fully polyclonal repertoire, we also examined the effect of Btk deficiency on the anergic, autoreactive-prone An1 subset in nontransgenic mice. The An1 subset is CD93+/CD23+/IgMlo. This subset cannot be examined in NOD mice because of technical issues with the AA4.1 (anti-CD93) Ab, so studies were performed using C57BL/6 mice. Fig. 1C shows representative dot plots of B220+ IgM+ live lymphocytes (left panels) gated on CD93+ cells depicting the An1 subset (CD23+/IgMlo; right panels) from Btk-sufficient and -deficient mice with endogenous BCRs. Fig. 1D and Table III show that Btk-deficient mice have significantly reduced percentages and numbers of An1 B cells (p < 0.01). These data are similar to previously published findings in the Btk-deficient BALB.xid model, in which this subset, then defined as T3, also was found to be decreased (34). Thus, Btk deficiency dramatically decreases the numbers of autoreactive-prone, anergic B cells in both a naturally occurring population, as well as in a well-studied anergic, anti-insulin–transgenic model.

FIGURE 1.

Btk deficiency reduces anti-insulin B cells and An1 cells in the spleen. (A and B) The expression of B220 and IgM and insulin reactivity were assessed in 125Tg/NOD Btk-sufficient or Btk-deficient splenocytes using flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots. Left panel is gated on live lymphocytes. Right panel is gated on B220+ IgMa+ live lymphocytes. (B) Average number (± SEM) of B cells. (C) Splenocytes were harvested, and CD93+ cells were identified in B220+ IgM+ live lymphocytes (left panels); CD93+-gated B cells were divided into the An1 subset (IgMlo CD23+) from WT/C57BL/6 Btk-sufficient or Btk-deficient mice (right panel). (D) Total number of An1 cells for Btk-sufficient or Btk-deficient mice. In (A) and (B), n ≥ 10, 8–15-wk-old male and female mice/group, n = 3 experiments. In (C) and (D), n ≥ 7, 8–10-wk-old male and female mice/group, n = 2 experiments. All mice had blood glucose < 200 mg/dl. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, two-tailed t test.

Table I.

125Tg B cell subset percentages

| Organ | B Cell Subseta | Btk Sufficient | Btk Deficient | p Value (t Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | Totalb | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 0.35 |

| Bone marrow | Pro/pre | 13.2 ± 1.9 | 19.5 ± 2.9 | 0.08 |

| Bone marrow | Immature | 42.4 ± 6.0 | 78.3 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Bone marrow | Mature Recirculating | 43.4 ± 6.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | Totalb | 14.0 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | T1 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 16.5 ± 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | T2 | 10.0 ± 1.8 | 22.2 ± 2.8 | 0.002 |

| Spleen | Follicular | 25.1 ± 3.2 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | Premarginal zone | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Spleen | Marginal zone | 57.5 ± 3.2 | 55.0 ± 4.2 | 0.65 |

| PLN | Totalb | 8.2 ± 4.0 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Pancreas | Totalb | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.03 |

Table II.

125Tg B cell subset numbers

| Organ | B Cell Subseta | Btk Sufficient (× 104 Cells) | Btk Deficient (× 104 Cells) | p Value (t Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | Totalb | 44.4 ± 10.6 | 73.8 ± 20.5 | 0.19 |

| Bone marrow | Pro/pre | 7.1 ± 2.8 | 14.9 ± 4.9 | 0.16 |

| Bone marrow | Immature | 17.9 ± 4.6 | 57.3 ± 15.6 | 0.013 |

| Bone marrow | Mature recirculating | 19.0 ± 5.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.008 |

| Spleen | Totalb | 1256.7 ± 152.5 | 62.8 ± 10.1 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | T1 | 31.9 ± 5.4 | 9.2 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | T2 | 124.1 ± 30.3 | 13.0 ± 1.8 | 0.0011 |

| Spleen | Follicular | 335.1 ± 79.1 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | Premarginal zone | 66.0 ± 16.0 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | Marginal zone | 699.6 ± 72.4 | 36.7 ± 8.2 | <0.001 |

| PLN | Totalb | 33.9 ± 19.7 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Pancreas | Totalb | 4.1 ± 1.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.014 |

Table III.

An1 B cell subset numbers and percentages

| Organ | Btk Sufficient (× 104 Cells) | Btk Deficient (× 104 Cells) | p Value (t Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| An1 subset (%)a | 7.0 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| An1 subset (no.; ×104 cells) | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

An1 subset identified as B220+ CD93 (AA4.1)+ CD23+ IgMlow.

Percentage of total B lymphocytes.

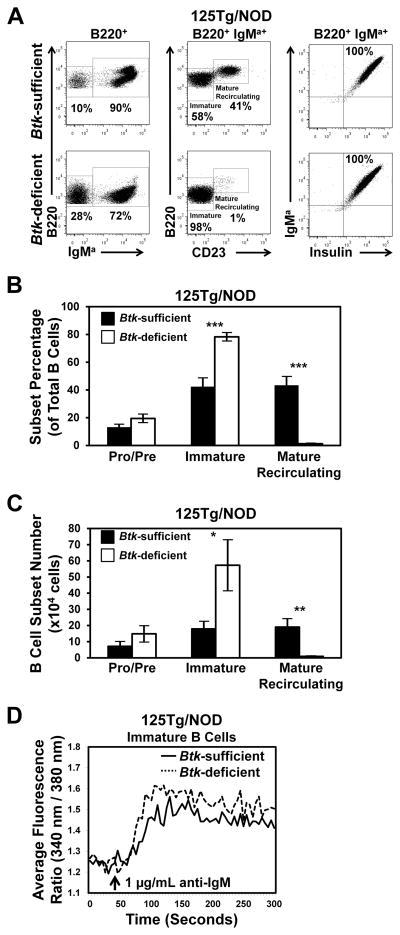

BTK is dispensable for development of immature anti-insulin B cells

B cell–developmental subsets were identified in freshly isolated bone marrow of Btk-sufficient or -deficient 125Tg/NOD mice using flow cytometry to detect B220, IgMa, and CD23 expression. Insulin-binding specificity was confirmed with biotinylated insulin staining detected by a streptavidin-fluorochrome conjugate. Representative plots are shown in Fig. 2A, and the average frequency ± SEM (Fig. 2B, Table I) or total number ± SEM (Fig. 2C, Table II) of pro and pre (B220+ IgMa−), immature (B220mid IgMa+ CD23−), or mature recirculating (B220high IgMa+ CD23+) B cells is shown. Btk deficiency confers a comparable or elevated frequency and number of immature B cells in the bone marrow of 125Tg/NOD mice. In contrast, mature recirculating B cell numbers are significantly reduced (0.9 ± 0.2 × 104 versus 19.0 ± 5.1 × 104 cells, p = 0.008).

FIGURE 2.

Anti-insulin immature B cells do not require BTK to develop or to mobilize calcium following BCR stimulation. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots of bone marrow isolates from Btk-sufficient or Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice. Left panel is gated on B220+ live lymphocytes. Middle and right panels are gated on B220+ IgMa+ live lymphocytes. The average (± SEM) percentages (B) or total numbers (C) of pro/pre (IgMa−), immature (IgMa+ CD23−), or mature recirculating (IgMa+ CD23+) B cells (B220+ live lymphocytes). n ≥ 8 male and female mice, 9–16 wk of age, n = 4 experiments. (D) Bone marrow cells from 125Tg/NOD Btk-sufficient or -deficient mice were cultured with IL-7 for 5 d and then for 2 d without IL-7 to generate naive immature B cells (32). Cells were stimulated, and calcium mobilization was measured as in Materials and Methods. Arrow indicates stimulation with 1 μg/ml anti-IgM. Data are representative of n ≥ 4 mice, n = 2 experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two-tailed t test.

BCR-mediated calcium flux in immature anti-insulin B cells does not require BTK

BCR signaling is known to be impaired in mature Btk-deficient B cells (35, 36). However, the fact that immature B cell development is unimpeded in Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice raises the question of whether BCR signaling in anti-insulin B cells occurs independently of BTK at this developmental stage. To test this, naive immature 125Tg B cells were generated using IL-7–driven culture, as previously described (Materials and Methods) (32). BCR-induced calcium mobilization was measured in Btk-sufficient and -deficient immature B cells following stimulation with anti-IgM. Interestingly, comparable calcium mobilization was observed in 125Tg/NOD immature B cells, regardless of BTK status (Fig. 2D). Impaired calcium flux was observed in mature Btk-deficient 125Tg B cells, as expected (data not shown). Consistent with the above data on B cell development, these data show that Btk deficiency does not impair calcium mobilization following BCR stimulation in immature 125Tg B cells, highlighting a major difference in signaling between immature and mature anti-insulin B cells.

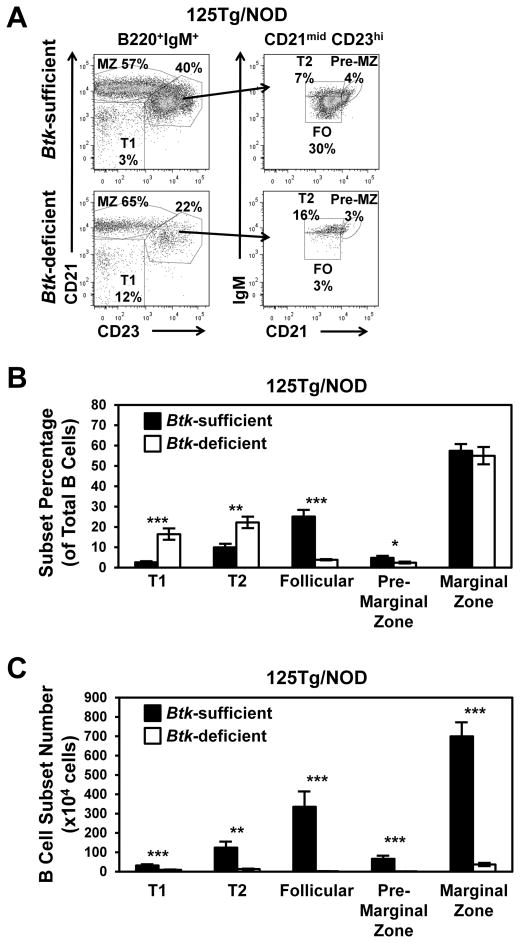

Btk deficiency results in loss of anti-insulin B cells at every developmental stage in the spleen

Btk deficiency in NOD mice with nontransgenic BCRs confers an 18% reduction in splenic B cell numbers (27). However, in 125Tg/NOD mice, Btk deficiency results in >90% loss of B cells (Fig. 1). In NOD mice with endogenous BCRs, Btk deficiency causes a partial block at the T2 to follicular B cell transition, as well as a small reduction in marginal zone B cell numbers (27). To address whether Btk deficiency affects anti-insulin B cell development differently, spleen B cell subsets were compared in Btk-sufficient and -deficient 125Tg/NOD mice. Fig. 3A shows the flow cytometry gating scheme to detect early transitional T1 (CD21low CD23low), late transitional T2 (CD21mid CD23high IgMhigh), follicular (CD21mid CD23high IgMmid), premarginal zone (CD21high CD23high IgMhigh), and marginal zone (CD21high CD23mid) B cells. Quantification of subset proportions for each genotype (Fig. 3B, Table I) shows that both early and late transitional components are relatively overrepresented in the setting of Btk deficiency, suggesting that there is a block in maturation beyond both of these checkpoints.

FIGURE 3.

Btk deficiency decreases the numbers of anti-insulin B cells at all developmental stages, with profound loss of mature subsets. Flow cytometry was used to analyze splenic B cell subsets in 125Tg/NOD mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots show the gating scheme for T1, T2, follicular, premarginal zone, and marginal zone B cells from Btk-sufficient (upper panels) and Btk-deficient (lower panels) 125Tg/NOD mice. Left panels: B220+ IgMa+ live lymphocytes; right panels: B220+ IgMa+ CD21mid CD23high live lymphocytes. The average (± SEM) percentages (B) or total numbers (C) of T1 (CD21low CD23low), T2 (CD21mid CD23high, IgMhigh), follicular (CD21mid CD23high, IgMmid), premarginal zone (CD21high, CD23high, IgMhigh), and marginal zone (CD21high CD23mid) B cells (B220+, IgM+ live lymphocytes) for Btk-sufficient and Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice. All mice had blood glucose < 200 mg/dl. In (B) and (C), n ≥ 10, 8–15-wk-old male and female mice/group, n = 3 experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two-tailed t test.

However, quantification of total cell numbers shows that anti-insulin B cells are lost at all phases of development (Fig. 3C, Table II). The number of follicular B cells in 125Tg/NOD Btk-deficient mice was reduced 99% compared with 125Tg/NOD Btk-sufficient mice (2.2 ± 0.3 × 104 versus 335.1 ± 79.1 × 104, p < 0.001). Although the frequency of marginal zone B cells was not different, the total number of marginal zone B cells was reduced 95% in Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice (36.7 ± 8.2 × 104 versus 699.6 ± 72.4 × 104, p < 0.001). The cell populations from which these mature subsets arise are also markedly reduced: the early transitional T1 subset is reduced by 71% (9.2 ± 1.4 × 104 versus 31.9 ± 5.4 × 104, p < 0.001), the late transitional T2 subset is reduced by 90% (13.0 ± 1.8 × 104 versus 124.1 ± 30.3 × 104, p = 0.0011), and the premarginal zone subset is reduced by 89% (1.7 ± 0.4 × 104 versus 66.0 ± 16.0 × 104, p < 0.001). These data show that anti-insulin B cell maturation and/or survival is more profoundly impaired by loss of BTK than is observed in the polyclonal repertoire of NOD mice with nontransgenic BCRs (27).

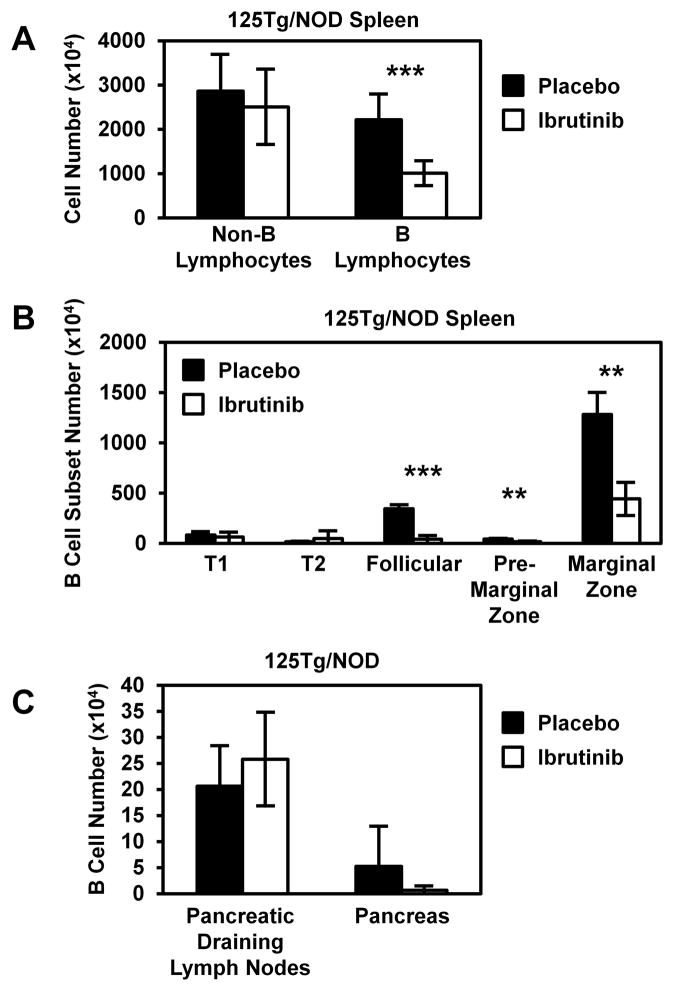

Kinase inhibition of BTK reduces mature, but not transitional, anti-insulin B cells

BTK is a complex protein with adapter, as well as kinase, functions that have independent effects on various aspects of B cell development and function (37, 38). Therefore, a kinase inhibitor of BTK, Ibrutinib (PCI-32765; a kind gift from Pharmacyclics) (23, 39), was used to test the effects of kinase inhibition on anti-insulin B cell development and survival. Ibrutinib chow or placebo chow was fed to 125Tg/NOD mice for 5–10 wk. The average inhibitor dosage was 38 mg/kg/d (sufficient to elicit 99% inhibitor function; personal communication, Pharmacyclics). Flow cytometry analysis of freshly isolated splenocytes was used to identify B cell subsets, as in Fig. 3. These data mirror the developmental alteration seen in 125Tg/NOD Btk-deficient mice. The number of B lymphocytes was decreased in ibrutinib chow–fed mice versus placebo chow–fed mice (10 ± 3 × 106 versus 22 ± 6 × 106 cells, p < 0.001), whereas no difference was observed in non-B lymphocyte numbers (25 ± 9 × 106 versus 29 ± 8 × 106 cells, Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, no significant difference was observed in T1 (63 ± 47 × 104 versus 83 ± 32 × 104 cells, p = 0.57) or T2 (49 ± 76 × 104 versus 17 ± 3 × 104 cells, p = 0.51) B cell subset numbers in the spleen. However, an 88% reduction in follicular (41 ± 37 × 104 versus 345 ± 38 × 104 cells, p < 0.001), a 60% reduction in premarginal zone (17 ± 5 × 104 versus 43 ± 6 × 104 cells, p = 0.0015), and a 65% reduction in marginal zone (443 ± 164 × 104 versus 1283 ± 217 × 104 cells, p = 0.002) B cell numbers was observed. In contrast, no significant difference was observed in the number of B cells in the pancreatic draining lymph nodes (26 ± 9 × 104 versus 21 ± 8 × 104, p = 0.49) or pancreas (0.66 ± 0.80 × 104 versus 5.2 ± 7.7 × 104, p = 0.36, Fig. 4C) of 125Tg/NOD mice treated with Ibrutinib. These data show that inhibition of BTK kinase function impairs the maturation and/or survival of anti-insulin B lymphocytes but that Ibrutinib does not block their trafficking to pancreatic draining lymph nodes or pancreas.

FIGURE 4.

Ibrutinib, a BTK kinase inhibitor, decreases the numbers of mature anti-insulin B cells in the spleen but not in the draining pancreatic lymph nodes or pancreas. 125Tg/NOD mice were fed 0.24 g ibrutinib/kg feed, for an average of 38 mg inhibitor/kg consumed per day per mouse (>24 mg/kg/d dosing recommended to achieve 99% inhibitor activity). After 5–10 wk, spleen, draining pancreatic lymph nodes, and pancreata were harvested, and flow cytometry was used to analyze B cell subsets. (A) The numbers of B lymphocytes (B220+ IgM+ live lymphocytes) and non-B lymphocytes (B220− IgM− live lymphocytes) were assessed in spleens (n = 6 placebo-treated [black] and n = 7 inhibitor-treated [white] male and female mice). (B) Spleen B cell subsets were identified, as in Fig. 3, and subset numbers were determined (n = 3 placebo-treated [black] and n = 3 inhibitor-treated [white] mice). (C) B cell numbers were assessed by flow cytometry in freshly isolated pancreatic draining lymph nodes and pancreata (n = 3 female mice/group). Mice were 12–13 wk old at the time of analysis. Error bars indicate SD. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two-tailed t test.

Anti-insulin B cells are preferentially susceptible to Btk deficiency

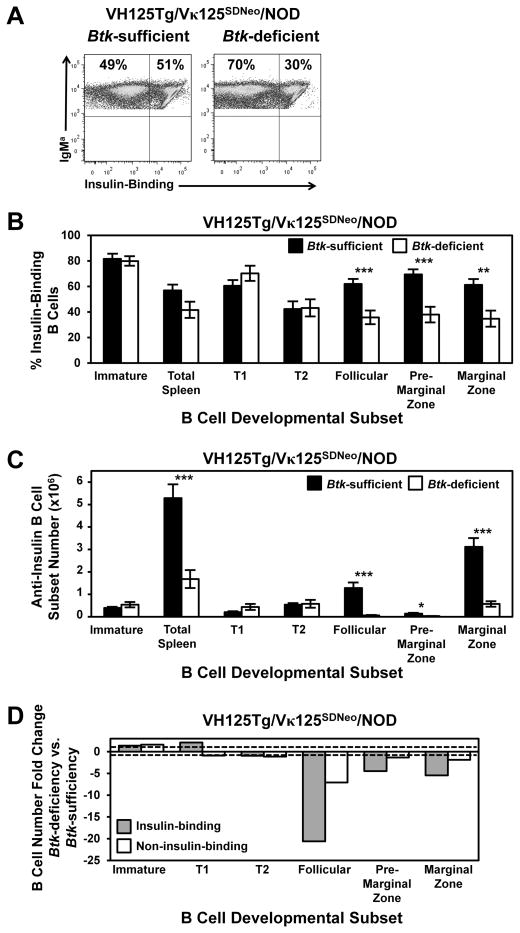

The dramatic reduction in mature B cell subsets in 125Tg/NOD mice compared with Btk-deficient NOD mice with endogenous BCRs suggests that autoreactive (anti-insulin) B cells rely more heavily on BTK-mediated signaling than do nonautoreactive B cells. However, the presence of a BCR transgene may have unrecognized effects that are unrelated to Ag specificity. Therefore, we used a novel BCR-transgenic model, in which an anti-insulin L chain is targeted to the Igκ locus to allow receptor editing (kindly provided by Dr. James Thomas, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). This model, VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo, provides the unique opportunity to track a substantial population of anti-insulin B cells (~50%) that develops alongside an equally large competing repertoire harboring the same BCR VH transgene (Fig. 5A, freshly isolated spleen is shown). Developmental subsets were characterized in the bone marrow and spleens of VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo/NOD Btk-deficient or -sufficient mice, as in Figs. 2 and 3, using flow cytometry (Fig. 5, Tables IV–VI). Btk deficiency has no effect on the proportion or number of insulin-binding B cells found among immature cells in the bone marrow (Fig. 5B, 5C, Tables IV, VI). Interestingly, the proportion and number of insulin-binding B cells in the transitional T1 and T2 stages in the spleen are unchanged by BTK loss in this model. However, the proportions and numbers of insulin-binding Btk-deficient B cells decrease markedly with BTK loss in the follicular (42%, 95%, respectively), premarginal zone (45%, 78%), and marginal zone (43%, 82%) subsets (Fig. 5B, 5C, Tables IV, VI).

FIGURE 5.

Anti-insulin B cells are selectively impaired for transition into follicular and marginal zone B cells in the absence of BTK. VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo/NOD mice were developed as in Materials and Methods, and bone marrow and splenocyte B cell subsets were identified as in Figs. 2 and 3. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of B220+ IgMa+–gated live lymphocytes from spleens, showing insulin binding by staining with labeled insulin. Average percentages (± SEM) (B) or total numbers (± SEM) (C) of insulin-binding B cells present in immature, T1, T2, follicular, premarginal zone, and marginal zone subsets. (D) The fold change in the number of insulin-binding B cells present in each subset from (C) was calculated by dividing the average number of B cells in the Btk-sufficient subset by the average number in the comparable subset from Btk-deficient mice (or the reverse for fold increase). The same was calculated for noninsulin-binding B cells. Dashed lines = 1 (no change). n ≥ 9 mice, n ≥ 2 experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two-tailed t test.

Table IV.

VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo B cell subset percentages

| Organ | B Cell Subseta | Btk Sufficient Total | Btk Deficient Total | p Value (t Test) | Btk Sufficient Insulin Binding | Btk Deficient Insulin Binding | p Value (t Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | Totalb | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 0.26 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bone marrow | Pro/pre | 29.9 ± 3.3 | 38.9 ± 4.8 | 0.14 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bone marrow | Immature | 46.7 ± 4.1 | 49.0 ± 4.1 | 0.70 | 81.6 ± 3.9 | 79.8 ± 3.6 | 0.75 |

| Bone marrow | Mature recirculating | 15.6 ± 3.3 | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 0.02 | 63.3 ± 5.7 | 44.8 ± 5.4 | 0.03 |

| Spleen | Totalb | 13.2 ± 1.0 | 6.4 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | 56.9 ± 4.4 | 41.5 ± 6.3 | 0.057 |

| Spleen | T1 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 15.6 ± 2.7 | <0.001 | 60.5 ± 4.2 | 70.2 ± 5.9 | 0.19 |

| Spleen | T2 | 14.8 ± 0.8 | 30.1 ± 3.2 | <0.001 | 42.3 ± 5.9 | 43.1 ± 6.7 | 0.93 |

| Spleen | Follicular | 21.9 ± 3.0 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | >0.001 | 61.9 ± 3.6 | 35.7 ± 5.3 | >0.001 |

| Spleen | Premarginal zone | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 0.72 | 69.4 ± 3.9 | 38.0 ± 6.1 | >0.001 |

| Spleen | Marginal zone | 54.2 ± 3.0 | 42.3 ± 3.8 | 0.02 | 61.2 ± 4.6 | 34.7 ± 6.3 | 0.003 |

| Pancreatic draining lymph nodes | Totalb | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | <0.001 | 43.9 ± 1.6 | 44.1 ± 7.2 | 0.98 |

| Pancreas | Totalb | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.03 | 45.8 ± 2.1 | 47.2 ± 8.6 | 0.87 |

B cell subsets identified as in Fig. 5.

“Total” indicates B lymphocyte percentage of total cells in the indicated organ.

N/A, Not applicable.

Table VI.

VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo noninsulin-binding and insulin-binding B cell subset numbers

| Organ | B Cell Subseta |

Btk Sufficient (× 104 Cells) Noninsulin Binding |

Btk Deficient (× 104 Cells) Noninsulin Binding |

p Value (t Test) |

Btk Sufficient (× 104 Cells) Insulin Binding |

Btk Deficient (× 104 Cells) Insulin Binding |

p Value (t Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | Immature | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 2.4 | 0.16 | 39.5 ± 4.9 | 54.1 ± 11.9 | 0.27 |

| Bone marrow | Mature recirculating | 6.8 ± 1.7 | 4.8 ± 1.5 | 0.39 | 9.1 ± 1.9 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 0.03 |

| Spleen | Totalb | 420.0 ± 72.4 | 224.9 ± 52.4 | 0.047 | 528.7 ± 61.7 | 168.1 ± 40.1 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | T1 | 15.3 ± 3.7 | 17.1 ± 3.7 | 0.73 | 20.8 ± 3.7 | 43.7 ± 13.3 | 0.10 |

| Spleen | T2 | 88.4 ± 13.9 | 77.6 ± 25.7 | 0.71 | 54.1 ± 7.0 | 57.8 ± 17.5 | 0.84 |

| Spleen | Follicular | 90.8 ± 21.4 | 12.8 ± 4.6 | 0.004 | 128.2 ± 24.6 | 6.2 ± 2.1 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | Premarginal zone | 8.4 ± 3.2 | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 0.58 | 13.9 ± 3.9 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 0.02 |

| Spleen | Marginal zone | 221.4 ± 40.1 | 118.5 ± 26.9 | 0.053 | 311.7 ± 39.2 | 57.2 ± 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Pancreatic draining lymph nodes | Totalb | 10.0 ± 3.6 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 0.06 | 7.2 ± 2.1 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.007 |

| Pancreas | Totalb | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.08 |

B cell subsets identified as in Fig. 5.

“Total” indicates total B cell number in the indicated organ.

The fold change in B cell numbers was calculated for each developmental subset, differentiating between insulin-binding and noninsulin-binding B cells from the same mice: the average number of insulin-binding Btk-sufficient follicular B cells was divided by the average number of insulin-binding Btk-deficient follicular B cells (or the reverse for fold increase). The same was also calculated for noninsulin-binding B cells. Btk deficiency preferentially reduced insulin-binding follicular (21-fold), premarginal zone (4-fold), and marginal zone (5-fold) B cell numbers compared with the reduction in noninsulin-binding follicular (7-fold), premarginal zone (no change), and marginal zone (2-fold) B cell numbers (Fig. 5D). These data confirm that self-reactive anti-insulin B cells depend more heavily on BTK than do nonautoreactive B cells and that this differential dependency emerges in the follicular, premarginal zone, and marginal zone subsets, rather than at the earlier transitional stages.

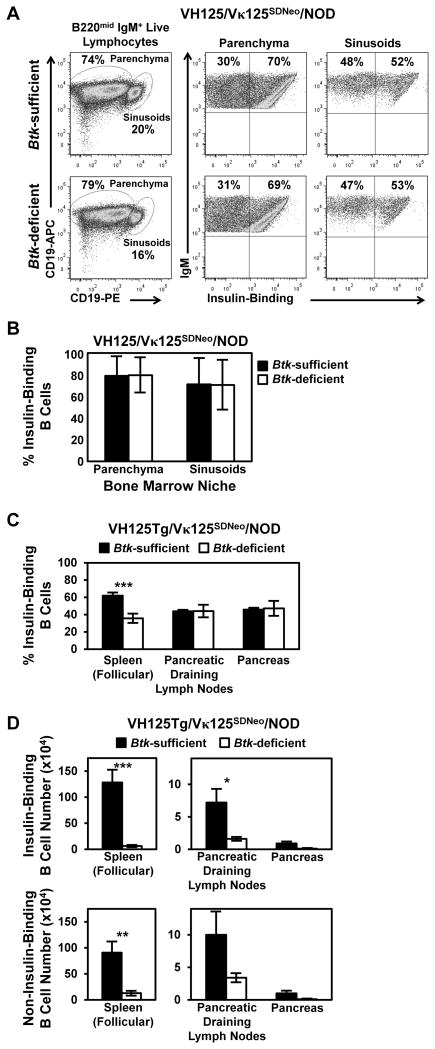

Btk-deficient insulin-binding B cells are normally positioned for bone marrow exit in the sinusoids

The VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo model also allows comparison of factors governing migration of insulin-binding and noninsulin-binding B cells from bone marrow to spleen, as well as their level of dependency on BTK. Because BTK was shown to support chemotactic responses (24, 25, 40), we evaluated whether anti-insulin B cells had altered reliance on BTK compared with nonautoreactive B cells. B lymphocytes in the bone marrow initially localize to the parenchyma, but they migrate to the sinusoids prior to egress to the periphery (33). To investigate whether BTK supports this process in insulin-specific B cells, we labeled sinusoid B cells by injecting anti-CD19–PE i.v., followed by euthanasia after 2 min. This preferentially labels B cells already in contact with blood flow in the sinusoids over those positioned away from the blood in the parenchyma (33). B cells were then harvested from bone marrow and stained with Abs to delineate immature B cells, as well as anti-CD19–allophycocyanin to help delineate the populations. Increased CD19-PE staining identifies B cells positioned in the sinusoids compared with parenchymal B cells that stain with lower levels of CD19-PE. Fig. 6A shows immature gated (IgM+ B220mid CD23−) sinusoidal and parenchymal populations from Btk-sufficient and Btk-deficient VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo/NOD mice. The data show that Btk deficiency does not affect the proportion of insulin-binding immature B cells in the sinusoids (Fig. 6B), suggesting that BTK-mediated signaling does not contribute preferentially to their exit from the bone marrow. Cell surface levels of CXCR5, which governs homing to secondary lymphoid follicles, were reduced in all BTK-deficient B cells, regardless of BCR specificity (data not shown). Therefore, we hypothesize that alteration in cellular homing is not sufficient to explain the preferential negative impact of BTK loss on mature anti-insulin B cells.

FIGURE 6.

Btk-mediated effects on factors related to B cell trafficking in VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo/NOD mice. (A and B) Sinusoidal positioning for bone marrow exit: anti-CD19–PE Ab was injected i.v., and VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo/NOD mice were sacrificed after 2 min to preferentially label sinusoidal B cells, as in Materials and Methods. (A) Bone marrow was harvested immediately, and Abs reactive with B220, IgM, CD19-allophycocyanin, and CD23 were used to identify immature B cells (left panels) that were divided into parenchymal (CD19-PEmid; middle panels) and sinusoidal (CD19-PEhigh; right panels) B cell populations. (B) Insulin-binding B cells were further identified using labeled insulin. Representative flow cytometry plots (A) and average percentages (± SD) of insulin-binding parenchymal or sinusoidal immature B cells (B) (n ≥ 5 mice, n = 2 experiments). Flow cytometry using labeled insulin was used to assess the proportion of anti-insulin B cells (C) and the number of insulin-binding B cells (D, top panels) or noninsulin-binding B cells (D, bottom panels) in spleen, pancreas, and draining pancreatic lymph nodes in Btk-sufficient and Btk-deficient mice (n ≥ 6 female mice, n ≥ 3 experiments). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two-tailed t test.

Btk deficiency does not preferentially prevent anti-insulin B cells from reaching the pancreatic draining lymph nodes and infiltrating the pancreas

Btk deficiency reduces anti-insulin B cells at mature stages in the spleen more markedly than noninsulin-binding B lymphocytes in the same mice (Fig. 5). To investigate whether Btk deficiency preferentially impacts the ability of anti-insulin B cells to home to the draining pancreatic lymph nodes and to infiltrate the pancreas in NOD mice, the average frequency of anti-insulin B cells present in these organs was compared between VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo/NOD Btk-sufficient and -deficient mice. As shown in Fig. 6C and Table IV, the proportion of anti-insulin B cells at these inflammatory sites is unchanged by BTK loss. Total B cell numbers are markedly reduced in both draining pancreatic lymph nodes and pancreata of Btk-deficient VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo/NOD mice, regardless of specificity, and anti-insulin B cell numbers reflect this overall reduction (Fig. 6D, Tables V, VI). The selective reduction in mature Btk-deficient anti-insulin B cells in the spleen relative to noninsulin-binding counterparts (21-fold versus 7-fold reduction) is less apparent in pancreatic draining lymph nodes (5-fold versus 3-fold reduction), and it is not reflected at the primary site of inflammation in the pancreas (9-fold versus 10-fold reduction) (Fig. 6D, Table VI). These data show that Btk deficiency does not preferentially impede anti-insulin B cell homing to these inflammatory sites, despite bias in the mature repertoire in the spleen.

Table V.

VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo B cell subset numbers

| Organ | B Cell Subseta | Btk Sufficient (× 104 Cells) | Btk Deficient (× 104 Cells) | p Value (t Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | Totalb | 102.2 ± 4.9 | 132.2 ± 19.3 | 0.15 |

| Bone marrow | Pro/pre | 31.0 ± 4.3 | 49.1 ± 8.5 | 0.07 |

| Bone marrow | Immature | 47.2 ± 3.8 | 66.4 ± 12.2 | 0.15 |

| Bone marrow | Mature recirculating | 16.1 ± 3.5 | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 0.11 |

| Spleen | Totalb | 948.7 ± 114.6 | 393.0 ± 78.2 | 0.0011 |

| Spleen | T1 | 35.5 ± 7.1 | 57.6 ± 13.4 | 0.15 |

| Spleen | T2 | 136.0 ± 16.1 | 125.0 ± 35.3 | 0.77 |

| Spleen | Follicular | 213.0 ± 42.5 | 18.2 ± 6.1 | <0.001 |

| Spleen | Premarginal zone | 22.4 ± 7.2 | 9.2 ± 2.5 | 0.12 |

| Spleen | Marginal zone | 516.6 ± 67.6 | 166.2 ± 32.4 | <0.001 |

| Pancreatic draining lymph nodes | Totalb | 17.4 ± 5.6 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 0.03 |

| Pancreas | Totalb | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.08 |

B cell subsets identified as in Fig. 5.

“Total” indicates Total B cell number in the indicated organ.

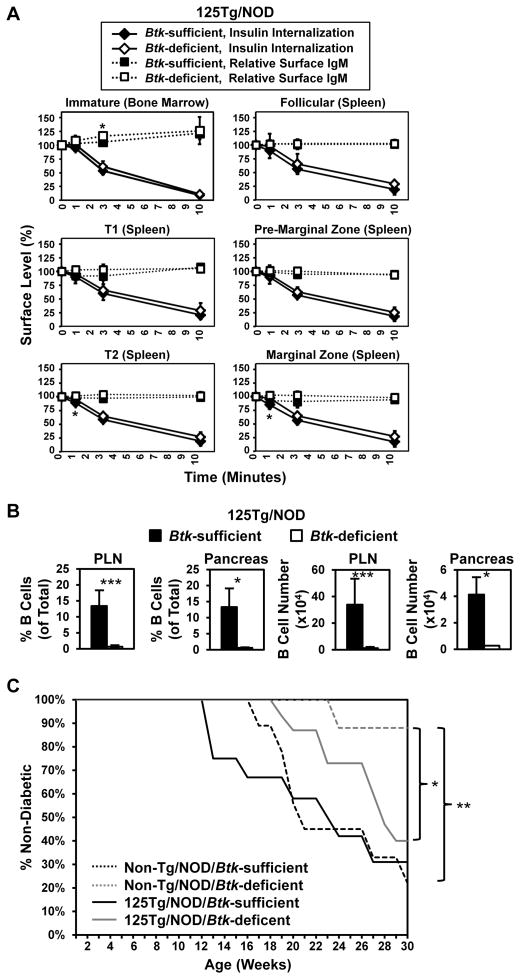

BCR internalization of insulin is Btk independent

To define the role of BTK in anti-insulin B cell function that promotes T1D, we analyzed factors related to disease outcomes in the 125Tg/NOD model, in which the BCR repertoire specificity is essentially uniform. Anti-insulin B cells can present insulin autoantigen to T cells and are necessary for disease in NOD mice (6–8). BCR internalization is critical for autoantigen processing and presentation to T cells. Loss of BTK reduces BCR internalization following anti-IgM stimulation (41). To identify whether BTK controls BCR internalization of a small, physiologic auto-antigen by anergic B cells, BCR internalization of insulin was assessed in Btk-deficient or -sufficient 125Tg/NOD mice. Surprisingly, the large majority of insulin was internalized with comparable kinetics in Btk-deficient and Btk-sufficient 125TgNOD mice within 10 min among all B cell subsets characterized (Fig. 7A). Surface IgM levels remained relatively constant during this time period in all subsets (Fig. 7A). Similar studies were performed using anti-IgMa stimulation. Consistent with previously published results (41), Btk-deficient follicular B cells showed diminished BCR internalization following stimulation with biotinylated anti-IgMa (data not shown). These data indicate that insulin internalization through the BCR is not altered by Btk deficiency and suggest that the mechanism of internalization of a small, soluble, low-affinity Ag may differ from that incurred by higher-affinity, cross-linking antigenic stimulation.

FIGURE 7.

B cells deficient for BTK internalize insulin auto-antigen and are capable of supporting diabetes relative to their BTK-sufficient counterparts. (A) 125Tg/NOD Btk-sufficient or Btk-deficient bone marrow or spleens were harvested, and cells were loaded with 50 ng/ml biotinylated insulin in media on ice, washed, and placed at 37°C for 0–10 min. Cells were then stained on ice with streptavidin-fluorochrome to detect remaining surface insulin, as well as with Abs reactive with B220, IgM, CD23 (bone marrow), and CD21 (spleen) to identify developmental subsets, as in Figs. 2 and 3. The MFI of insulin-biotin/streptavidin-fluorochrome (or IgM) at each time point was divided by the insulin-biotin/streptavidin-fluorochrome (or IgM) MFI at t = 0, such that 0 min = 100% expression for insulin (or IgM) on the cell surface. Insulin internalization (solid lines) and relative surface IgM (dashed lines) are plotted. The average ± SD is shown (n = 4 Btk-sufficient and n = 6 Btk-deficient male and female mice, 8–13 wk of age; n = 3 experiments). *p < 0.05, Btk-sufficient mice versus Btk-deficient mice, two-tailed t test. (B) Flow cytometry was used to assess the proportion of total (left panels) and number of (right panels) insulin-binding B cells in draining pancreatic lymph nodes (PLN) and pancreas (live B220+ IgMa+ lymphocytes) in Btk-sufficient or Btk-deficient mice (n ≥ 9, 9–15-wk-old female nondiabetic mice). (C) Diabetes onset was monitored in 125Tg/NOD Btk-sufficient (n = 12), 125Tg/NOD Btk-deficient (n = 15), Non-Tg/NOD Btk-sufficient (n = 9), and Non-Tg/NOD Btk-deficient (n = 8) female mice. Mice were considered diabetic after two consecutive blood glucose readings > 200 mg/dl. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, log-rank test.

Btk-deficient 125Tg B cells support diabetes development in NOD mice

Btk deficiency protects against T1D in NOD mice with non-transgenic BCRs (27). Disease is restored in that model when an anti-insulin BCR H chain transgene (VH125Tg) is introduced. VH125Tg/NOD/Btk-deficient mice have reduced, but measurable, numbers of anti-insulin B cells, as well as a large B cell population with a broad repertoire of noninsulin-specific B cells that may include other autoantigen specificities (27). In contrast, the 125Tg/NOD/Btk-deficient mice described in this report have very few B cells remaining; nearly all of them are specific for insulin, providing the opportunity to determine directly whether anergic, anti-insulin B cells require BTK-mediated signaling to support development of T1D. The number of anti-insulin B cells was reduced in both Btk-deficient pancreatic draining lymph nodes (1.2 ± 1.1 × 104 versus 33.9 ± 19.7 × 104 cells, p < 0.001) and pancreata (0.3 ± 0.1 × 104 versus 4.1 ± 1.3 × 104 cells, p = 0.014) (Fig. 7B, Table II). As shown in Fig. 7C, diabetes onset is delayed in Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice; however, by age 30 wk, the proportion with disease approaches that of their Btk-sufficient 125Tg/NOD littermates (60 versus 69%, p = 0.235). In contrast, despite having such low numbers of B cells, Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice have significantly higher levels of disease than do Btk-deficient nontransgenic NOD controls expressing endogenous BCR repertoires (12%, p = 0.045). Nontransgenic/NOD Btk-deficient mice are protected from disease compared with nontransgenic/NOD Btk-sufficient mice, (p = 0.007), as previously reported (27). These data show that low numbers of residual anti-insulin B lymphocytes in Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice can still support T1D.

Discussion

Autoreactive B cells that escape central tolerance in an anergic state have altered signaling responses compared with normal naive B cells (1, 42, 43), providing a potential opportunity to target these cells to treat or prevent autoimmune diseases. The data presented in this article show that anergic anti-insulin 125Tg B cells are exquisitely sensitive to loss of BTK. This BTK dependence of autoreactive-prone cells is mirrored in the reduction of the physiologically anergic An1 cell population. The VH125/Vκ125SDNeo model, in which roughly half of peripheral B cells bind insulin, confirms that mature insulin-specific B cells depend more heavily on BTK than do nonautoreactive B cells. The BTK kinase inhibitor, Ibrutinib, also affects mature anti-insulin B cell subsets preferentially, suggesting that activation of the kinase domain contributes to mature anti-insulin B cell development and/or survival.

Surprisingly, mature anti-insulin B cells internalize insulin autoantigen normally in the absence of BTK. Despite multiple defects, anti-insulin B cells can still home to inflamed islets and induce T1D, although with slightly delayed kinetics. This disease-related finding differs from that of BTK deficiency in NOD mice with endogenous BCRs, which significantly reduces the incidence of T1D (27). Because identifiable autoreactive B cells in the general repertoire of WT/NOD mice (as well as in humans with T1D) are rare (44), it is possible that a 95% reduction in their numbers as a result of BTK deficiency could decrease disease incidence.

In tracking the role of BTK through the developmental stages of tolerant anti-insulin 125Tg B cells, the data show that immature cells in the bone marrow develop and flux calcium normally in the absence of BTK (Fig. 2). These findings highlight a major difference in how immature and mature anti-insulin B cells signal through the BCR. Cell loss begins between the bone marrow and the early transitional T1 stage in Btk-deficient 125Tg B cells, where there is a 71% loss of cell numbers (Fig. 3, Table II). At the late transitional T2 stage, Btk-deficient 125Tg B cells, like their nontransgenic Btk-deficient counterparts with endogenous BCRs, have increased levels of surface IgM, commensurate with a block in maturation through this stage (27). However, unlike Btk-deficient mice with endogenous BCRs, there is a failure to increase T2 numbers, which is the normal result when cells destined for the follicular compartment are held back (27). Thus, it is likely that there is both a maturational block at T2 in Btk-deficient anti-insulin B cells and a loss of cells at that juncture that is more dramatic than the numbers alone would indicate.

Mature anti-insulin B cells clearly depend exquisitely on BTK, because follicular and marginal zone subsets are almost completely depleted in its absence. The VH125/Vκ125SDNeo model is especially useful in determining the role of Ag specificity at this stage, because anti-insulin follicular, premarginal zone, and marginal zone B cells are preferentially depleted compared with noninsulin-binding counterparts from the same animals (Fig. 5, Tables IV–VI). This may indicate that Ag engagement of the BCR provides an essential, positive selective signal mediated by BTK. The similar phenotype incurred by the BTK inhibitor, Ibrutinib, which blocks activation of the kinase domain while leaving the adapter function intact, further suggests that this may be the case (Fig. 4).

Of note, VH125/Vκ125SDNeo cells used in these experiments retain a neomycin-resistance cassette that enhances replacement of the anti-insulin Vκ, possibly by promoter augmentation of germline transcription through the κ locus (R.H. Bonami, A.R. Rachakonda, C. Hulbert, and J.W. Thomas, manuscript in preparation). Thus, although it is useful for analyzing differences in cell fates of the resulting insulin-binding versus noninsulin-binding populations, possible effects of the cassette on receptor editing precludes conclusions regarding BTK contributions in this area. Nevertheless, VH125/Vκ125SDNeo mice still provide a unique tool for teasing out the effects of autoreactivity versus transgene effects. For example, Btk-deficient 125Tg B cells show similar maturational blocks as Btk-deficient transgenic 3-83μδ B cells on the nondeleting H2-Kd background (37). The 3-83 BCR recognizes H2-Kk/b, resulting in cellular deletion when expressed on that background but not on the H2-Kd background. Nevertheless, when Btk deficiency was tested in 3-83μδ mice on the nondeleting background, the transgenic B cells were nearly all depleted, recapitulating many of the other findings that we report in this article for the 125Tg system, including an increased proportion of T1 cells (Fig. 3). The conclusion drawn from those findings was that a preformed BCR transgene results in faster transition out of the bone marrow and higher dependence on BTK as a result. However, in the VH125/Vκ125SDNeo model, we see identical BTK-mediated outcomes on insulin binders and noninsulin binders all the way through the T2 stage, with differential depletion of insulin binders emerging only at the more mature stages, arguing against an effect that is limited to timing of the transition out of the bone marrow (Fig. 5, Tables IV–VI). These new data suggest that the autoreactive specificity confers increased BTK dependency at maturation, in addition to transgene effects that may be associated with expedited bone marrow exodus. It is possible that the 3-83 BCR may recognize H2-Kd, or another unidentified autoantigen, at similar affinity to insulin; therefore, it may share some autoreactive properties with the anti-insulin 125Tg BCR, a viewpoint suggested by previous work regarding receptor editing in the 3-83 model (45). Both of these studies contrast with a new report regarding transgenic AM14 rheumatoid factor B cells, which recognize IgG2a with low affinity (Kd = 2.2 × 106) (46, 47). Genetic deficiency of BTK in this AM14 model depletes the transgenic autoreactive cells only to the same extent that the endogenous repertoire is depleted, further emphasizing that BTK requirements depend on the nature and affinity of the Ag (46, 47).

VH125/Vκ125SDNeo mice also allow analysis of insulin-specific B cell invasion of islets relative to noninsulin-binding counterparts in the same mice, which is normally a difficult task because the amount of overall islet inflammation varies significantly from mouse to mouse. Btk-deficient insulin-binding B cells are found in the pancreatic islets and draining pancreatic lymph nodes in equivalent proportions to their noninsulin-binding counterparts, regardless of BTK status, despite being preferentially culled during development in the spleen (Figs. 5, 6, Tables IV–VI), indicating that Btk-deficient insulin-binding B cells are equally adept at invading islets as are their noninsulin-binding counterparts. Of note, however, noninsulin-binding B cells in islets may differ from those in the spleen, because they are likely to be enriched for unidentified autoreactive specificities, and BTK also may support these other autoreactive B cells or may mediate responses to inflammatory cytokines, regardless of specificity.

Surprisingly, Btk-deficient anti-insulin B cells are able to internalize insulin Ag as well as their Btk-sufficient counterparts (Fig. 7). This is in contrast to other published work suggesting that BTK is required for Ag internalization (41). One key difference is the nature of the Ag being internalized. A small, physiologic Ag, such as insulin, may interact differently with the BCR compared with a strongly cross-linking Ag of high affinity, such as anti-IgM. We hypothesize that differences in signaling requirements exist for insulin internalization compared with large, multivalent Ags. The Kendall laboratory also found that 125Tg B cells, which are anergic, internalize Ag more efficiently than do nonanergic cells, which may also be a factor (8). Btk-deficient 125Tg/NOD mice develop diabetes (Fig. 7), despite having very few B cells, suggesting that they retain Ag-presenting function, because that is their role in the disease process (6, 8). This may have important implications for how a broad class of autoantigens is processed and presented to provoke autoimmunity and, thus, guide rationale for therapeutic targeting of this critical process.

Taken together, these data indicate that anergic, autoreactive B cells rely on BTK-mediated signaling for maturation or survival, but they can still traffic to inflamed tissues, internalize Ag, and promote cell-mediated autoimmunity without it. Thus, targeting of BTK may be most effective in reducing autoreactive cell numbers, rather than impairing their disease-related functions. This has clinical significance because a mAb that specifically depletes anti-insulin B cells was shown to prevent disease in NOD mice (44). Selectively targeting autoreactive B cells through BTK inhibition has the added advantage of not requiring prior knowledge of Ag specificity. The observation that loss of BTK in nontransgenic/NOD mice dramatically reduces serum anti-insulin IgG, without altering total IgG (27), supports the concept that anti-insulin B cells can be selectively targeted by inhibiting BTK function in a fully polyclonal repertoire. Thus, the greater dependence of anti-insulin B cells on BTK relative to nonautoreactive B cells suggests that therapeutic inhibition of BTK function may hold promise for the treatment of T1D and possibly other autoimmune diseases mediated by B cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants T32 HL069765 and T32 AR059039 and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant 3-2013-121 (to R.H.B.); National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK084246 and K08 DK070924, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant 1-2008-108, and a gift from Pharmacyclics (to P.L.K.); Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant 1-2005-167 (to James W. Thomas); and Grant R21AI 088511 (to W.N.K.). The Vanderbilt Medical Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource is supported by the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485) and the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center (DK058404). The Vanderbilt Transgenic/Embryonic Stem Cell Shared Resource Core is supported by The Cancer Center Support Grant (National Institutes of Health Grant CA68485), the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center (National Institutes of Health Grant DK20593), the Vanderbilt Brain Institute, and the Center for Stem Cell Biology.

We thank Roberta Pelanda (University of Colorado, Denver, CO) for providing the targeting construct and Southern blot probe DNA and the Vanderbilt Transgenic Mouse/Embryonic Stem Cell Shared Resource for the development of Vκ125SDNeo mice. We thank Dr. James Thomas for kindly providing the VH125Tg/Vκ125SDNeo/NOD mice, as well as for critical manuscript review. We thank Dr. Betty Y. Chang (Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, CA) for scientific insights regarding Ibrutinib, as well as for provision of the inhibitor. Flow cytometry data acquisition was performed in the Vanderbilt Medical Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource.

Abbreviations in this article

- BTK

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

- ES

embryonic stem

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- T1

early transitional

- T2

late transitional

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Merrell KT, Benschop RJ, Gauld SB, Aviszus K, Decote-Ricardo D, Wysocki LJ, Cambier JC. Identification of anergic B cells within a wild-type repertoire. Immunity. 2006;25:953–962. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duty JA, Szodoray P, Zheng NY, Koelsch KA, Zhang Q, Swiatkowski M, Mathias M, Garman L, Helms C, Nakken B, et al. Functional anergy in a subpopulation of naive B cells from healthy humans that express autoreactive immunoglobulin receptors. J Exp Med. 2009;206:139–151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quach TD, Manjarrez-Orduno N, Adlowitz DG, Silver L, Yang H, Wei C, Milner EC, Sanz I. Anergic responses characterize a large fraction of human autoreactive naive B cells expressing low levels of surface IgM. J Immunol. 2011;186:4640–4648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zikherman J, Parameswaran R, Weiss A. Endogenous antigen tunes the responsiveness of naive B cells but not T cells. Nature. 2012;489:160–164. doi: 10.1038/nature11311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojas M, Hulbert C, Thomas JW. Anergy and not clonal ignorance determines the fate of B cells that recognize a physiological autoantigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:3194–3200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acevedo-Suárez CA, Hulbert C, Woodward EJ, Thomas JW. Uncoupling of anergy from developmental arrest in anti-insulin B cells supports the development of autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2005;174:827–833. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulbert C, Riseili B, Rojas M, Thomas JW. B cell specificity contributes to the outcome of diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:5535–5538. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendall PL, Case JB, Sullivan AM, Holderness JS, Wells KS, Liu E, Thomas JW. Tolerant anti-insulin B cells are effective APCs. J Immunol. 2013;190:2519–2526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroer JA, Bender T, Feldmann RJ, Kim KJ. Mapping epitopes on the insulin molecule using monoclonal antibodies. Eur J Immunol. 1983;13:693–700. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830130902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benschop RJ, Brandl E, Chan AC, Cambier JC. Unique signaling properties of B cell antigen receptor in mature and immature B cells: implications for tolerance and activation. J Immunol. 2001;167:4172–4179. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kühn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin mu chain gene. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dal Porto JM, Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Mills D, Pugh-Bernard AE, Cambier J. B cell antigen receptor signaling 101. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:599–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petro JB, Castro I, Lowe J, Khan WN. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase targets NF-kappaB to the bcl-x promoter via a mechanism involving phospho-lipase C-gamma2 following B cell antigen receptor engagement. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan WN, Alt FW, Gerstein RM, Malynn BA, Larsson I, Rathbun G, Davidson L, Müller S, Kantor AB, Herzenberg LA, et al. Defective B cell development and function in Btk-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:283–299. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinners NP, Carlesso G, Castro I, Hoek KL, Corn RA, Woodland RT, Scott ML, Wang D, Khan WN. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase mediates NF-kappa B activation and B cell survival by B cell-activating factor receptor of the TNF-R family. [Published erratum appears in 2007 J. Immunol.179: 6369.] J Immunol. 2007;179:3872–3880. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antony P, Petro JB, Carlesso G, Shinners NP, Lowe J, Khan WN. B-cell antigen receptor activates transcription factors NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells) and NF-kappaB (nuclear factor kappaB) via a mechanism that involves diacylglycerol. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:113–115. doi: 10.1042/bst0320113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antony P, Petro JB, Carlesso G, Shinners NP, Lowe J, Khan WN. B cell receptor directs the activation of NFAT and NF-kappaB via distinct molecular mechanisms. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan WN. Regulation of B lymphocyte development and activation by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. Immunol Res. 2001;23:147–156. doi: 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petro JB, Khan WN. Phospholipase C-gamma 2 couples Bruton’s tyrosine kinase to the NF-kappaB signaling pathway in B lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1715–1719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petro JB, Rahman SM, Ballard DW, Khan WN. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is required for activation of IkappaB kinase and nuclear factor kappaB in response to B cell receptor engagement. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1745–1754. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kil LP, de Bruijn MJ, van Nimwegen M, Corneth OB, van Hamburg JP, Dingjan GM, Thaiss F, Rimmelzwaan GF, Elewaut D, Delsing D, et al. Btk levels set the threshold for B-cell activation and negative selection of autoreactive B cells in mice. Blood. 2012;119:3744–3756. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-397919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whyburn LR, Halcomb KE, Contreras CM, Lowell CA, Witte ON, Satterthwaite AB. Reduced dosage of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase uncouples B cell hyperresponsiveness from autoimmunity in lyn−/− mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:1850–1858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aalipour A, Advani RH. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a promising novel targeted treatment for B cell lymphomas. Br J Haematol. 2013;163:436–443. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang BY, Francesco M, De Rooij MF, Magadala P, Steggerda SM, Huang MM, Kuil A, Herman SE, Chang S, Pals ST, et al. Egress of CD19(+)CD5(+) cells into peripheral blood following treatment with the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib in mantle cell lymphoma patients. Blood. 2013;122:2412–2424. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-482125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Rooij MF, Kuil A, Geest CR, Eldering E, Chang BY, Buggy JJ, Pals ST, Spaargaren M. The clinically active BTK inhibitor PCI-32765 targets B-cell receptor- and chemokine-controlled adhesion and migration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:2590–2594. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-390989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi D, Ciardullo C, Spina V, Gaidano G. Molecular bases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in light of new treatments. Immunol Lett. 2013;155:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kendall PL, Moore DJ, Hulbert C, Hoek KL, Khan WN, Thomas JW. Reduced diabetes in btk-deficient nonobese diabetic mice and restoration of diabetes with provision of an anti-insulin IgH chain transgene. J Immunol. 2009;183:6403–6412. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serreze DV, Fleming SA, Chapman HD, Richard SD, Leiter EH, Tisch RM. B lymphocytes are critical antigen-presenting cells for the initiation of T cell-mediated autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:3912–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serreze DV, Chapman HD, Varnum DS, Hanson MS, Reifsnyder PC, Richard SD, Fleming SA, Leiter EH, Shultz LD. B lymphocytes are essential for the initiation of T cell-mediated autoimmune diabetes: analysis of a new “speed congenic” stock of NOD.Ig mu null mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2049–2053. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noorchashm H, Lieu YK, Noorchashm N, Rostami SY, Greeley SA, Schlachterman A, Song HK, Noto LE, Jevnikar AM, Barker CF, Naji A. I-Ag7-mediated antigen presentation by B lymphocytes is critical in overcoming a checkpoint in T cell tolerance to islet beta cells of nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:743–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pelanda R, Schwers S, Sonoda E, Torres RM, Nemazee D, Rajewsky K. Receptor editing in a transgenic mouse model: site, efficiency, and role in B cell tolerance and antibody diversification. Immunity. 1997;7:765–775. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henry RA, Acevedo-Suárez CA, Thomas JW. Functional silencing is initiated and maintained in immature anti-insulin B cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:3432–3439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira JP, An J, Xu Y, Huang Y, Cyster JG. Cannabinoid receptor 2 mediates the retention of immature B cells in bone marrow sinusoids. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:403–411. doi: 10.1038/ni.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allman D, Lindsley RC, DeMuth W, Rudd K, Shinton SA, Hardy RR. Resolution of three nonproliferative immature splenic B cell subsets reveals multiple selection points during peripheral B cell maturation. J Immunol. 2001;167:6834–6840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fluckiger AC, Li Z, Kato RM, Wahl MI, Ochs HD, Longnecker R, Kinet JP, Witte ON, Scharenberg AM, Rawlings DJ. Btk/Tec kinases regulate sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ following B-cell receptor activation. EMBO J. 1998;17:1973–1985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takata M, Kurosaki T. A role for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B cell antigen receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase C-gamma 2. J Exp Med. 1996;184:31–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Middendorp S, Hendriks RW. Cellular maturation defects in Bruton’s tyrosine kinase-deficient immature B cells are amplified by premature B cell receptor expression and reduced by receptor editing. J Immunol. 2004;172:1371–1379. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Middendorp S, Dingjan GM, Maas A, Dahlenborg K, Hendriks RW. Function of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase during B cell development is partially independent of its catalytic activity. J Immunol. 2003;171:5988–5996. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Honigberg LA, Smith AM, Sirisawad M, Verner E, Loury D, Chang B, Li S, Pan Z, Thamm DH, Miller RA, Buggy JJ. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13075–13080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004594107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Gorter DJ, Beuling EA, Kersseboom R, Middendorp S, van Gils JM, Hendriks RW, Pals ST, Spaargaren M. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase and phospholipase Cgamma2 mediate chemokine-controlled B cell migration and homing. Immunity. 2007;26:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma S, Orlowski G, Song W. Btk regulates B cell receptor-mediated antigen processing and presentation by controlling actin cytoskeleton dynamics in B cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:329–339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fulcher DA, Basten A. Reduced life span of anergic self-reactive B cells in a double-transgenic model. J Exp Med. 1994;179:125–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yarkoni Y, Getahun A, Cambier JC. Molecular underpinning of B-cell anergy. Immunol Rev. 2010;237:249–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henry RA, Kendall PL, Thomas JW. Autoantigen-specific B-cell depletion overcomes failed immune tolerance in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:2037–2044. doi: 10.2337/db11-1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun U, Rajewsky K, Pelanda R. Different sensitivity to receptor editing of B cells from mice hemizygous or homozygous for targeted Ig trans-genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7429–7434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050578497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nündel K, Busto P, Debatis M, Marshak-Rothstein A. The role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in the development and BCR/TLR-dependent activation of AM14 rheumatoid factor B cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:865–875. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0313126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barral P. Editorial: Btk – friend or foe in autoimmune diseases? J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:859–861. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0513279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]