Abstract

Objectives

Compulsive hoarding is a debilitating, chronic disorder, yet we know little about its onset, clinical features, or course throughout the life span. Hoarding symptoms often come to clinical attention when patients are in late life, and case reports of elderly hoarders abound. Yet no prior study has examined whether elderly compulsive hoarders have early or late onset of hoarding symptoms, whether their hoarding symptoms are idiopathic or secondary to other conditions, or whether their symptoms are similar to compulsive hoarding symptoms seen in younger and middle-aged populations. The objectives of this study were to determine the onset and illustrate the course and clinical features of late life compulsive hoarding, including psychiatric and medical comorbitities.

Methods

Participants were 18 older adults (≥60) with clinically significant compulsive hoarding. They were assessed using structured interviews, including the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID I), Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS), and UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale (UHSS). Self-report Measures Included the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), and Savings Inventory-Revised (SI-R). Psychosocial and medical histories were also obtained. To determine age at onset, participants were asked to rate their hoarding symptoms and describe major life events that occurred during each decade of their lives.

Results

Results show that (1) onset of compulsive hoarding symptoms was initially reported as being in mid-life but actually found to be in childhood or adolescence. No subjects reported late onset compulsive hoarding. (2) Compulsive hoarding severity increased with each decade of life. (3) Comorbid mood and anxiety disorders were common, but only 16% of patients met criteria for OCD if hoarding symptoms were not counted toward the diagnosis. (4) The vast majority of patients had never received treatment for hoarding. (5) Older adults with compulsive hoarding were usually socially impaired and living alone.

Conclusions

Compulsive hoarding is a progressive and chronic condition that begins early in life. Left untreated, its severity increases with age. Compulsive hoarding should be considered a distinct clinical syndrome, separate from OCD. Unfortunately, compulsive hoarding is largely unrecognized and untreated in older adults.

Keywords: compulsive hoarding, obsessive-compulsive disorder, older adults

Introduction

Hoarding is defined as the acquisition of and inability to discard items even though they appear to have no value (Frost and Gross, 1993). The prevalence of clinically significant hoarding in the general population has been projected at 4% (5.3%, weighted) (Samuels et al., 2008). Frost and Hartl (1996) developed criteria for clinically significant compulsive hoarding: (1) the acquisition of and failure to discard a large number of possessions that appear (to others) to be useless or of limited value, (2) living or work spaces sufficiently cluttered so as to preclude activities for which those spaces were designed, and (3) significant distress or impairment in functioning caused by the hoarding behavior or clutter. Hoarding and saving symptoms are part of a discrete clinical syndrome that includes the core symptoms of urges to save, difficulty discarding, excessive acquisition, and clutter, as well as indecisiveness, perfectionism, procrastination, disorganization, and avoidance (Steketee and Frost, 2003). In addition, many compulsive hoarders are slow in completing tasks, frequently late for appointments, and display circumstantial, over-inclusive language. Patients with prominent hoarding and saving who display these other associated symptoms are thus considered to have the ‘compulsive hoarding syndrome’ (Saxena et al., 2002; Steketee and Frost, 2003).

Compulsive hoarding is a progressive, chronic condition (Grisham et al., 2006) and is more prevalent in older than younger age groups (Samuels et al., 2008). Hoarding symptoms often come to clinical attention when patients are in late life, and case reports of elderly hoarders abound (Hogstel, 1993; Stein et al., 1997; Rosenthal et al., 1999; Marx and Cohen-Mansfield, 2003). One investigation found that of all complaints to health departments about hoarding, 40% required involvement by an elder service agency (Frost et al., 2000). Additionally, several studies have found that clinical samples of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) patients with prominent hoarding symptoms were significantly older than non-hoarding OCD subjects (e.g., Frost et al., 2000; Saxena et al., 2002). To our knowledge, only one prior study has investigated compulsive hoarding in a large sample of elderly persons. Kim and colleagues (2001) conducted interviews with elder service providers who reported on 62 elderly persons who met clinical criteria for compulsive hoarding (Frost and Hartl, 1996). Service providers who had observed the homes and living conditions of these older hoarders reported that most (73%) were female, 82% lived alone, and 55% had never been married. They commonly hoarded the same items saved by younger hoarders in prior studies, such as paper, containers, clothing, food, and books. Nearly all had severe clutter, and most had substantial disorganization in their homes. Sixty-four percent of the elderly hoarders showed some difficulty with self-care. In the view of the service providers, hoarding and clutter constituted a physical health threat for 81% of their hoarding clients, including fire hazards, fall risks, and unsanitary conditions. Of note, only 24% of these hoarders were reported to display any cognitive impairment. Yet the majority had little or no insight into the irrationality of their hoarding behavior. Partial and even complete removal of clutter was not effective and typically led to recluttering of cleared areas (Kim et al., 2001). Unfortunately, that study did not examine any of the elderly hoarders themselves, nor did it assess age at onset, symptom severity, or comorbidity. There has not been any structured psychiatric investigation of the onset, course, and comorbidity patterns in older adults with compulsive hoarding.

In studies of young and middle-aged compulsive hoarders, the initial onset of hoarding symptoms was found to be in childhood or adolescence (Frost and Gross, 1993; Grisham et al., 2006; Samuels et al., 2002; Seedat and Stein, 2002; Wheaton et al., 2008). The course tends to be chronic and progressive, with severe levels of hoarding starting in the mid-30s. Typically, hoarders tend to seek treatment in mid-life (e.g., Frost et al., 2000). In contrast to this progressive, developmental course, hoarding may also begin following brain injury. Damage to the medial prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex has been found to result in new onset of hoarding and acquiring behaviors in patients who had no prior history of hoarding (Hahm et al., 2001; Volle et al., 2002; Anderson et al., 2005). Further, it has been suggested that hoarding can develop following a traumatic life event (Cromer et al., 2007). Despite these findings, we know nothing about the onset or course of compulsive hoarding in older adults. No prior study has examined whether elderly compulsive hoarders have early or late onset of hoarding symptoms, or whether their hoarding symptoms are idiopathic or secondary to other conditions. Thus, it is unclear if life events, head injuries, or neurological illnesses affect onset and course of compulsive hoarding symptoms in older persons.

Historically, compulsive hoarding has been studied within the context of OCD. Recent research has suggested that compulsive hoarding is a distinct variant or subtype of OCD that has different neurobiology (Saxena et al., 2004), genetics (Zhang et al., 2002; Lochner et al., 2005), symptom structure (Pertusa et al., 2008), and treatment response (e.g., Mataix-Cols et al., 2002; Saxena et al., 2002; Steketee and Frost, 2003). OCD patients with hoarding symptoms also have greater psychiatric comorbidity than non-hoarding OCD patients (Lochner et al., 2005; Samuels et al., 2002, 2007). A variety of comorbid Axis I disorders such as social phobia, major depression, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), bipolar II, dysthymia, and schizophrenia (Lochner et al., 2005; Luchins et al., 1992; Samuels et al., 2007; Steketee and Frost, 2003) have been found in middle-aged hoarding samples.

Hoarding is particularly dangerous for older persons, who may have physical and cognitive limitations. Possible consequences include increased fall risk, fire hazard, food contamination, social isolation, and medication mismanagement (e.g., Frost and Gross, 1993; Kim et al., 2001). Hoarding symptoms have also been observed in older adults with dementia (e.g., Hwang et al., 1998). Diogenes syndrome has been used to describe a cluster of problems (domestic squalor, hoarding of trash, gross self-neglect, poor personal hygiene, isolation) sometimes associated with late-life hoarding (Clark et al., 1975; Greve et al., 2004; Montero-Odasso et al., 2005). However, this is not a medical term and does not apply to the many compulsive hoarders who do not show self-neglect, poor personal hygiene, or social isolation. Although no structured psychiatric interview was used, hoarding symptoms have also been found in relatively healthy older adult populations (Marx and Cohen-Mansfield, 2003). Little is known about psychiatric or medical comorbidity in the late-life compulsive hoarding population.

The overall objective of this investigation was to determine age at onset and describe the clinical characteristics of older adults with significant compulsive hoarding symptoms, including course, impairment, and medical and psychiatric comorbidity. We expected that onset would occur in childhood and teenage years, with severity increasing with age. A better understanding of compulsive hoarding in late life is the first step toward accurate detection and better treatments.

Method

Sample and data collection

This study was approved by the University of California, San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System Institutional Review Boards. After providing a complete description of the study to the participants, written informed consent was obtained. Participants were recruited throughout San Diego County, University of California, San Diego Psychiatry Clinics, and the VA San Diego Healthcare System, through posted flyers. The flyers included symptoms of compulsive hoarding and the age criteria of the project (age ≥60). The majority of participants were recruited for a diagnostic assessment study that provided feedback on their diagnoses and referrals. Three participants were recruited for a treatment study. This was a self-selected, self-referred sample. Participants were seen in two face-to-face, 60 min interviews. Their first assessment was for psychiatric history and standardized symptom severity ratings. Information on medical conditions was collected by either a clinical psychologist or psychiatry resident. When possible, chart reviews were also performed. The second interview was to examine comorbidities utilizing a structured diagnostic interview schedule. Additionally, participants rated their hoarding symptom severity throughout their life span.

Measures

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) was used as a gross screen of cognitive abilities. OCD symptom severity was measured with the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS; Goodman et al., 1989). The YBOCS has demonstrated good consistency (.69–.91) and validity (Goodman et al., 1989; Woody et al., 1995). The UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale (UHSS; Saxena et al., 2007) was utilized to assess compulsive hoarding symptom severity and impairment. The UHSS has not yet been fully validated. Participants were also given the self-report Savings Inventory-Revised (SI-R; Frost et al., 2004) to assess hoarding severity. The SI-R has demonstrated reliability (.92) and good convergent validity with other scales of hoarding. The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) was used to assess impairment in work, social/leisure, and family domains (Sheehan et al., 1996). The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1998) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1988) were used to assess anxiety and depression symptoms. Psychiatric comorbidities were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First, et al., 1997) and Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Lecrubier et al., 1997). The method of Grisham et al. (2006) was used to determine age at onset of hoarding symptoms. Participants were asked to recall two major life events during each decade of their lives. After they recalled two events they were then asked to rate the severity of any compulsive hoarding behaviors (excessive acquiring, difficulty discarding, and/or clutter) from 0 (none) to 3 (extreme).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, participants had to have clinically significant compulsive hoarding, defined by the following criteria: (1) significant amount of clutter in active living spaces; (2) the urge to collect, buy, or acquire things; (3) an extreme reluctance to part with items; (4) hoarding symptoms or clutter cause significant distress or impairment in functioning; (5) symptom duration of at least 6 months; (6) hoarding and clutter are not accounted for by other psychiatric conditions; (7) a score of at least 40 on the SI-R; and (8) a score of at least 20 on the UHSS. Data from self-report ratings, clinician administered scales, and information from the psychiatric interview were utilized to make a determination. Inclusion based on the above criteria was decided on based on consensus conference including at least two licensed professionals with expertise in compulsive hoarding. Exclusion criteria included active substance use disorders, psychosis, or scores below 23 on the MMSE. However, no prospective subjects had these problems, so none were excluded.

Statistical methods

The data were examined for normal distribution and missing values. Descriptive statistics are provided for demographic variables, symptom severity, age at onset of compulsive hoarding symptoms, and psychiatric and medical comorbidities.

Results

Demographics

Participants included 18 older adults (11 men, 7 women) with a mean age of 67.5, range 60– 87 (Table 1). Most were not currently married (77%)—due to divorce (39%), never having married (33%), or death of spouse (5%). Only the married individuals were living with another person (22%). The participants were largely retired (66%), with 22% looking for work/unemployed and 11% currently working. On average, participants had 15.5 years of education. The sample was mostly Caucasian (1 African American, 1 Hispanic).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of 18 older adults with compulsive hoarding

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 67.5 (7) | 60–87 |

| Gender M: | 11, F: 7 | |

| Education | 15.5 (2) | 12–18 |

| Marital status | ||

| Divorced | 7 | |

| Single | 6 | |

| Married | 4 | |

| Widowed | 1 | |

| Veteran status | 10 | |

| Family history of hoarding | 6 | |

| Employment | ||

| Retired | 11 | |

| Unemployed | 4 | |

| Working | 3 | |

| Comorbid medical conditions | ||

| Hypertension | 11 | |

| Head injury | 7 | |

| Arthritis | 5 | |

| Gastric problems | 4 | |

| Sleep apnea | 4 | |

| Chronic pain | 3 | |

| Seizure | 2 | |

| Osteoporosis | 2 | |

| Stroke | 2 | |

| Cancer | 2 | |

| Eye disorders | 2 | |

| Diabetes | 1 | |

| Asthma/COPD | 1 | |

| Comorbid psychiatric conditions | ||

| MDD | 5 | |

| Dysthymia | 4 | |

| OCD | 3 | |

| PTSD | 2 | |

| GAD | 1 | |

| Social phobia | 1 | |

| Agoraphobia | 1 | |

| Anxiety disorder NOS | 1 |

Symptom severity

The SDS measure indicated overall moderate impairment (Table 2). Scores on the UHSS (mean 24.8) and SI-R (mean 58.1) indicated clinically significant, moderate levels of hoarding severity. YBOCS scores (mean 17.5) were also in the clinically significant range. Anxiety and depression symptom severity measures demonstrated variability and were within the mild range.

Table 2.

Rating scale scores of 18 older adults with compulsive hoarding

| Rating scale | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Mini-Mental Status Exam | 28 (0.7) |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 16.2 (11) |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 13.3 (10) |

| Savings Inventory-Revised | 58.1 (11) |

| UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale | 24.8 (7.4) |

| Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale | 17.5 (5) |

| Sheehan Disability | 17 (7) |

Age at onset

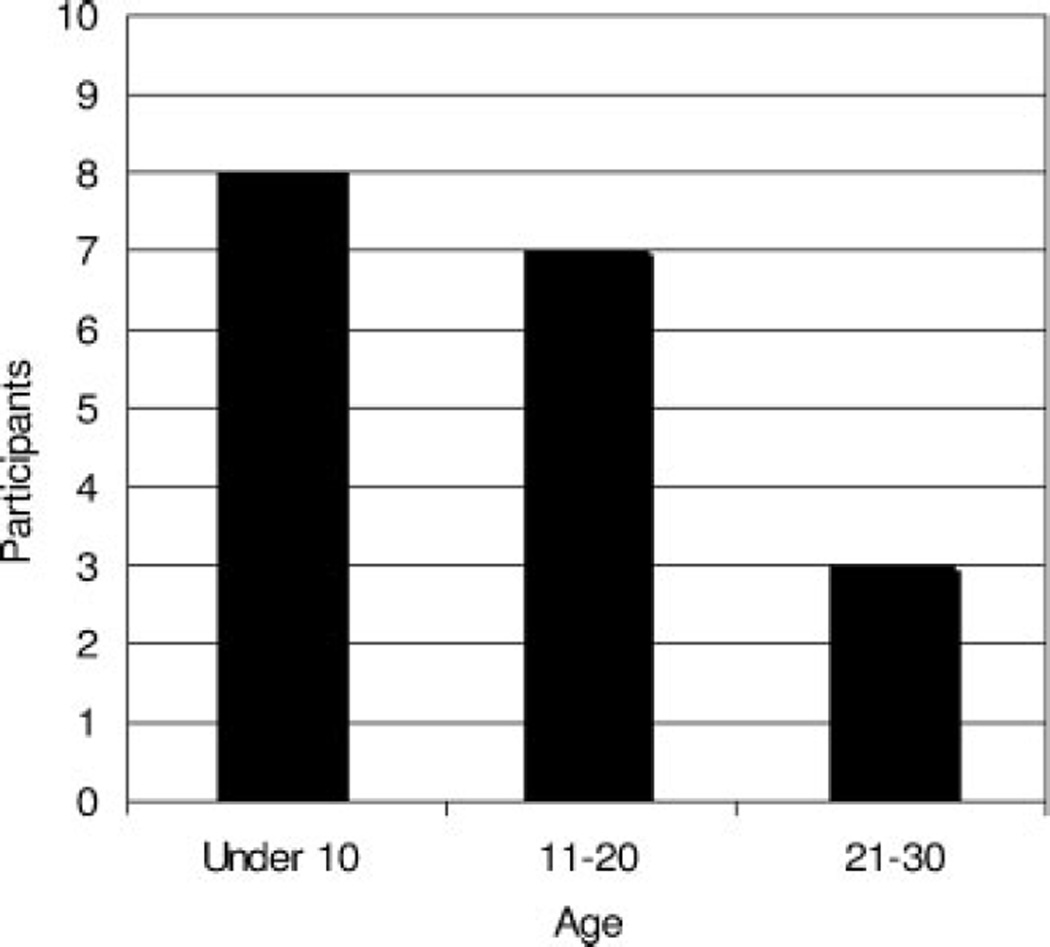

During the initial psychiatric interview, participants were asked, ‘When did your hoarding start?’, which produced an average reported age at onset of 29.5 (13.8). The earliest age of onset was 4 years old. However, using the Grisham et al.s’ (2006) method of decade review, eight subjects reported onset prior to the age of 10, seven reported onset during their teenage years (between age 11–20), and three reported onset in their 20s (see Figure 1). No subjects reported onset after their 20s. No participants cited a life event as the cause or trigger of their hoarding behaviors. The majority of life events reported during these decades were not traumatic and included events such as starting school, getting a driver’s license, or joining the military. Only four subjects reported probable negative life events (2 illnesses, 2 moves).

Figure 1.

Age at onset of initial compulsive hoarding symptoms in 18 older adults with compulsive hoarding.

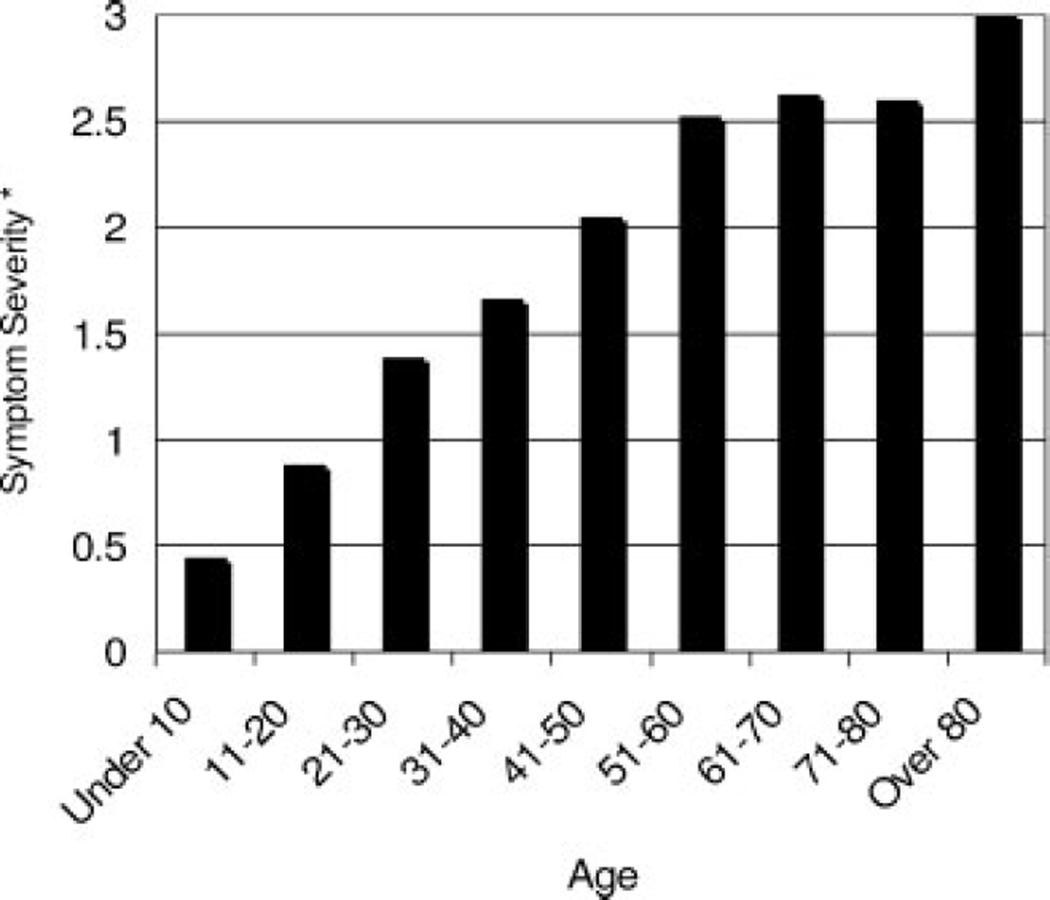

Course

All participants reported that the severity of their compulsive hoarding symptoms gradually increased over the life course. Moderate levels of hoarding severity were reached by the subjects’ 40s, and severity continued to increase thereafter (see Figure 2). At the point at which symptom severity increased from mild to moderate, subjects reported a mixture of positive, negative, and neutral events. Only two subjects reported an abrupt increase (none to moderate and mild to severe) in hoarding symptoms. During that time, both subjects relocated, and one also got a divorce. Of the two subjects with comorbid PTSD, one believed that her hoarding symptoms worsened after the trauma, and one did not.

Figure 2.

Mean hoarding severity rating during each decade of life in 18 older adults with compulsive hoarding. Mean symptom severity* of any hoarding symptoms where 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = extreme.

Current psychiatric comorbidity

The most commonly found comorbidity was major depression (28%), followed by dysthymia (22%), OCD (not counting compulsive hoarding symptoms) (16%), and PTSD (11%). Anxiety disorder NOS, GAD, social phobia, and agoraphobia were also diagnosed (5%, or 1 subject each). There was a bimodal distribution of comorbidity—one set of 10 participants had other mood or anxiety disorders (55%), whereas another group of 8 had no comorbidities. There were no significant differences found between these groups on symptom severity measures. No subjects had active substance use disorders, psychosis, or any form of dementia (per structured interview and chart review). Approximately one-third (28%) indicated a past history of substance abuse or dependence.

Psychiatric treatment and family history

Seventy-two percent of participants had received psychiatric care at some point in their lives. Of those who had received psychiatric care, 66% were given the diagnosis of major depression, and 28% were given the diagnosis of OCD by a physician, psychiatrist, or psychologist. Half of the participants (50%) were currently taking psychiatric medications. Two participants had received psychiatric treatment (medication management) for hoarding symptoms. No subjects had ever received behavioral treatment for hoarding. For the majority of the participants (88%), this was the first time they had sought out any type of service for compulsive hoarding. One participant received a citation from the county to clear her living space. One third (33%) of subjects reported having at least one immediate family member with hoarding behaviors. Sixty-one percent of subjects reported first-degree relatives with mood, anxiety, and/or substance use disorders.

Neurological history and physical health

Seven participants (39%) reported having had a significant head injury with loss of consciousness. The majority (71%) of these participants reported that the hoarding symptoms were already present prior to the head injury. Two participants reported that the head injury occurred at roughly the same time hoarding began, although neither attributed hoarding to their injury. Other significant medical illnesses that could affect neurocognitive functioning included hypertension (61%), sleep apnea (22%), seizures (11%), and stroke (11%). Comorbid medical conditions are listed in Table 1.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study ever to assess age at onset, course, clinical characteristics, and comorbidity in elderly compulsive hoarders. Overall, elderly hoarders appeared quite similar to their younger and middle-aged counterparts in previous reports, with a few important exceptions. We found that, in elderly compulsive hoarders: (1) hoarding symptoms initially appeared during childhood and adolescence in nearly every subject, and before age 30 in every subject; (2) hoarding severity increased with age; (3) approximately half had other psychiatric disorders but only 16% had OCD; and (4) compulsive hoarding was grossly underdetected and untreated. We also found additional evidence for significant social impairment in compulsive hoarders.

Our findings support the notion that compulsive hoarding is a chronic, progressive illness that starts early in life (e.g., Grisham et al., 2006; Seedat and Stein, 2002). Carefully reviewing the history of hoarding symptoms is important, because patients’ first responses are frequently inaccurate. When initially asked during their first psychiatric interview, ‘When did your problems with hoarding start?’, participants reported an onset around the age of 30. However, when they systematically reviewed each decade of their lives, they recalled problems with acquiring, discarding, and/or clutter starting much earlier in their lives—the majority during childhood and adolescence. Thus, previous work using subjective reports of onset should be interpreted with caution. We were surprised that no subjects reported onset after the third decade of life, given the prior reports of late life-onset hoarding caused by brain injury or degeneration (Anderson et al., 2005; Nakaaki et al., 2007). Although a number of participants reported head injury, the majority reported that the injury occurred after hoarding onset. We did not find any true late-onset hoarding, suggesting that it may be less common than previously believed.

Further, no participants reported onset of compulsive hoarding due to a negative life event or medical problem. Life events surrounding initial onset were typically normal developmental experiences (e.g., getting a driver’s license, going to school, joining the military). Only a few reported possible negative life events (2 childhood illness, 2 moving out of state) at onset. This is in contrast to other reports that cite negative life events or brain injury as a catalyst for hoarding behaviors (Grisham et al., 2006; Cromer et al., 2007; Anderson et al., 2005). Inaccurate initial recall of hoarding onset may have led to the idea that hoarding onset occurred only after extreme life events, when in fact it may have been present all along.

All of the subjects reported increasing hoarding severity with age. None reported a decrease in severity with age. This is particularly interesting given findings of decreasing prevalence of other Axis I and II disorders in late life (Kessler et al., 2005). Symptom severity scores were quite similar to those of younger adult hoarders in prior studies (e.g., Frost et al., 2004; Saxena et al., 2007). In the current sample, life events did not affect onset but may have affected symptom severity. Participants did report a number of mixed (positive, negative, and neutral) life events surrounding an increase to moderate levels of hoarding. Life events may accelerate hoarding when stressors occur. Further, severity increases across the life span may be confounded due to a combination of aging-associated factors such as social isolation and loss of resources. Additionally, the sheer build-up of possessions and clutter over time may influence self-reported increased severity. Overall, these findings highlight that compulsive hoarding is a chronic condition that worsens with age. Life events and age-associated factors may affect the course of hoarding.

Compared to other studies using mid-life samples, our subjects had a relatively narrow range of comorbidities consisting only of mood and anxiety disorders. No participants were found to have schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or active substance use disorders. Additionally, despite recruitment from geriatric psychiatrists and neurologists, we did not have any participants with dementia or significant cognitive impairment. Two groups emerged with respect to comorbidity—one group with one or more comorbid mood or anxiety disorders (mainly major depression), and the other without any comorbid psychiatric disorders. Further, we found a relatively lower prevalence of these comorbidities (OCD, GAD, and social phobia) than did other studies (e.g., Steketee and Frost, 2003). This may be reflective of possible lower prevalence rates of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults (Kessler et al., 2005). Most importantly, only 16% of participants met criteria for OCD. This is similar to the rates of comorbid nonhoarding OCD found in other samples of compulsive hoarders (e.g., Hartl et al., 2005). These results provide continuing support for the utility of differentiating compulsive hoarding from OCD. Given the ample evidence that these syndromes are discrete with respect to symptom profile, treatment response, and heritability, these disorders must be conceptualized and treated differently (Saxena, 2007).

For the majority of participants, this was the first time they had sought care for hoarding despite at least moderate symptom severity beginning several decades ago. Established treatments for compulsive hoarding are relatively new, so it was not expected that they would have had access to treatment earlier in life. However, it is noteworthy that only two participants had received any type of treatment for compulsive hoarding. This is alarming, given that many had received psychiatric care in the past, yet their compulsive hoarding went undetected and untreated. Providers should be educated about compulsive hoarding symptoms and how to assess them when conducting evaluations with seniors.

Consistent with other reports, the majority of older compulsive hoarders in this study demonstrated social impairment and lived alone (Kim et al., 2001). During the diagnostic interview, the majority of participants reported that their living conditions kept them from having house guests due to embarrassment. In our sample, only 22% were married and living with another person. This is in contrast to 2005 US Census data showing that 75.5% of men and 54% of women between the ages of 65–74 were married and living with their spouse.

This study has several limitations. Caution should be taken, given this small, self-selected sample. Our subjects were relatively well educated and had insight into their difficulties with hoarding. Those with low insight do not seek out resources for hoarding. Retrospective recall bias may influence reports of onset and course. Although we attempted to have participants recall other life events during each time period to assist with orientation, we were not able to verify the accuracy of their reports with other sources. In addition, we did not confirm their ratings of clutter by direct observation of their homes and living conditions. Ideally, home visits would be conducted to confirm self-report ratings. Nevertheless, the SI-R and YBOCS are well-validated measures and represent the gold standard for assessment of OCD and compulsive hoarding symptoms.

Implications for this study include the great need for early detection and intervention for compulsive hoarding. Given the progressive nature of hoarding, treatment should be offered during initial stages. Moreover, mental health clinicians need to screen for acquiring, discarding, and clutter problems in patients presenting for mood or anxiety disorders, since patients may not reveal these symptoms unless asked directly. Future studies will be necessary to determine whether elderly compulsive hoarders have similar treatment responses as younger and middle-aged patients.

Key Points.

Compulsive hoarding starts in childhood and adolescence.

Compulsive hoarding severity increases with age.

Compulsive hoarding is a distinct variant of OCD.

Compulsive hoarding is often undetected and untreated in older adults.

Acknowledgments

The research is supported by Obsessive Compulsive Foundation, K23 MH067643, R01 MH069433, and the VA San Diego Healthcare System. This work is supported by a grant from the Obsessive Compulsive Foundation to Dr. Ayers, a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH067643) to Dr. Wetherell, and a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH069433) to Dr. Saxena.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None known. Dr. Ayers, Dr. Saxena, Dr. Golshan, and Dr. Wetherell report no affiliation with or financial interest in any commercial organization that might pose a conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson S, Damasio H, Damasio AR, et al. A neural basis for collecting behaviour in humans. Brain. 2005;128:201–212. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R, Garbin M. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Clark AN, Mankikar GD, Gray I. Diogenes syndrome. A clinical study of gross neglect in old age. Lancet. 1975;1(7903):366–368. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromer KR, Schmid NB, Murphy DL. Do traumatic events influence the clinical expression of compulsive hoarding? Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2581–2581. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, (SCID-II) Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini mental state: a practical method of grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Resource. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Gross RC. The hoarding of possessions. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:367–381. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90094-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Hartl T. A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:341–350. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Grisham J. Measurement of compulsive hoarding: saving inventory-revised. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1163–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams LF, et al. Mood, personality disorder symptoms and disability in obsessive compulsive hoarders: a comparison with clinical and nonclinical controls. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve KW, Curtis KL, Bianchini KJ, et al. Personality disorder masquerading as dementia: a case of apparent diogenes syndrome. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:703–705. doi: 10.1002/gps.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham J, Frost RO, Steketee G, et al. Age of onset of compulsive hoarding. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm DS, Kang Y, Cheong SS, Na DL. A compulsive collecting behavior following an A-com aneurysmal rupture. Neurology. 2001;56:398–400. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl TL, Duffany SR, Allen GJ, et al. Relationships among compulsive hoarding, trauma, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogstel MO. Understanding hoarding behavior in the elderly. Am J Nurs. 1993;93:42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JP, Tsai SJ, Yang CH, et al. Hoarding behavior in dementia: a preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Steketee G, Frost RO. Hoarding by elderly prople. Health Soc Work. 2001;26:176–184. doi: 10.1093/hsw/26.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E. The mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): a short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Lochner C, Kinnear CJ, Hemmings SM, et al. Hoarding in obsessivecompulsive disorder: clinical and genetic correlates. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1155–1160. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchins DJ, Goldman MB, Leib M, et al. Repetitive behaviors in chronically institutionalized schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 1992;8:119–119. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx MS, Cohen-Mansfield J. Hoarding behavior in the elderly: a comparison between community-dwelling persons and nursing home residents. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15:289–306. doi: 10.1017/s1041610203009542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM, Greist JH. Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: results from a controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71:255–262. doi: 10.1159/000064812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Odasso M, Schapira M, Duque G. Is collectionism a diagnostic clue for diogenes syndrome? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(8):709–711. doi: 10.1002/gps.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaaki S, Murata Y, Sato J, et al. Impairment of decision-making cognition in a case of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) presenting with pathologic gambling and hoarding as the initial symptoms. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2007;20:121–125. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e31804c6ff7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertusa A, Fullana MA, Singh S, et al. Compulsive hoarding: OCD symptom, distinct clinical syndrome, or both? Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1289–1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Stelian J, Wagner J, et al. Diogenes syndrome and hoarding in the elderly: case reports. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1999;36:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels J, Bienvenu OJ, III, Riddle MA, et al. Hoarding in obsessive compulsive disorder: results from a case-control study. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:517–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, III, Pinto A, et al. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Behav Res Ther. 2007;4:673–686. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Grados MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(7):836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Maidment KM, Vapnik T, et al. Obsessive-compulsive hoarding: symptom severity and response to multi-modal treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Brody A, Maidment K, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive hoarding. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1038–1048. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, et al. Paroxetine treatment of compulsive hoarding. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(6):481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S. Is compulsive hoarding a genetically and neurobiologically discrete syndrome? Implications for diagnostic classification. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:380–384. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat S, Stein DJ. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders: a preliminary report of 15 cases. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56:17–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Laszlo B, Marais E, et al. Hoarding symptoms in patients on a geriatric psychiatry inpatient unit. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:1138–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost RO. Compulsive hoarding: current status of the research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:905–927. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volle E, Beato R, Levy R, Dubois B. Forced collectionism after orbitofrontal damage. Neurology. 2002;58:488–490. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton M, Cromer K, Lasalle-Ricci VH, et al. Characterizing the hoarding phenotype in individuals with OCD: associations with comorbidity, severity and gender. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody SR, Steketee G, Chambless DL. Reliability and validity of the Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:597–605. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00076-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. Older adults in 2005 population profile of the United States: Dynamic Version, viewed 13 January 2009. http://www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/files/dynamic/OLDER.pdf.

- Zhang H, Leckman JF, Pauls DL, et al. Genomewide scan of hoarding in sib pairs in which both sibs have Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:896–904. doi: 10.1086/339520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]