Abstract

Disease is a ubiquitous and powerful evolutionary force. Hosts have evolved behavioural and physiological responses to disease that are associated with increased survival. Behavioural modifications, known as ‘sickness behaviours’, frequently involve symptoms such as lethargy, somnolence and anorexia. Current research has demonstrated that the social environment is a potent modulator of these behaviours: when conflicting social opportunities arise, animals can decrease or entirely forgo experiencing sickness symptoms. Here, I review how different social contexts, such as the presence of mates, caring for offspring, competing for territories or maintaining social status, affect the expression of sickness behaviours. Exploiting the circumstances that promote this behavioural plasticity will provide new insights into the evolutionary ecology of social behaviours. A deeper understanding of when and how this modulation takes place may lead to better tools to treat symptoms of infection and be relevant for the development of more efficient disease control programmes.

Keywords: social modulation, disease spread, mating, territoriality, parental care, social hierarchy

1. Introduction

‘Yo soy yo y mi circunstancia’ (‘I am myself and my circumstance’, [1], p. 43)

Disease is a ubiquitous and powerful evolutionary force. As a result, hosts have evolved behavioural and physiological responses that increase survival under infection [2]. Behavioural modifications, known as ‘sickness behaviours’, frequently involve symptoms, such as lethargy, somnolence and anorexia. While historically disregarded by physicians as mere side effects of the disease, sickness behaviours are increasingly viewed as an adaptive response [3,4]. A shared feature of these behavioural responses is an overall reduction in activity, which is thought to preserve metabolic resources that can then be allocated to fighting the infection [3,5] and, in the case of anorexia, to reduce nutrients that are essential for bacterial growth [5–7].

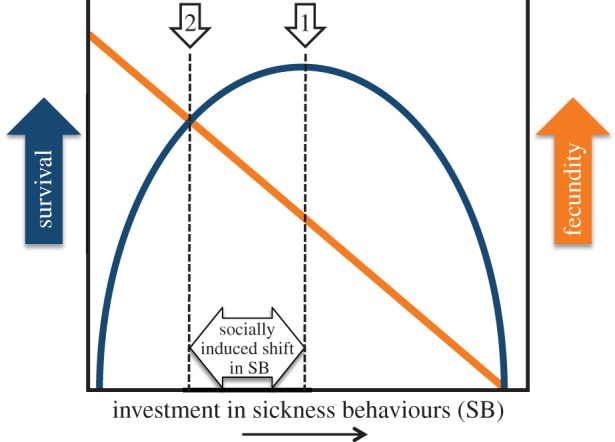

Life-history theory predicts that when circumstances are such that survival and reproduction are in conflict, the amount of investment in sickness behaviours should shift (figure 1). The question is thus: ‘when should animals experience symptoms of sickness and when should they suppress them?’ In this review, I focus on research demonstrating that a diversity of social contexts can act as potent modulators of sickness behaviours. Exploring these reports brings us closer to understanding what conditions lead infected animals to alter investment in sickness behaviours. The study of this behavioural plasticity can give us new perspectives on social behaviour. While appropriate social interactions are relevant for fitness, they also create opportunities for disease transmission. I argue that furthering our understanding of when and how the modulation of sickness behaviours occurs might be relevant for improving the health and management of animals in captivity and the control of disease spread in captive and wild populations. Finally, I point out clinical implications derived from understanding the neuroendocrine control of this phenomenon.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of how modulation of sickness behaviours can occur due to the social environment. Survival (blue curve): during disease, adopting sickness behaviours should increase survival to a certain extent. Prolonged/extreme sickness behaviours should then impact survival negatively, by increasing the likelihood of animals suffering from predation, further parasitism or, eventually, death by starvation. The shape of the survival curve will vary with how critical the expression of sickness behaviours is towards fighting the specific infection (not represented). Fecundity (orange curve): as more time and energy is being invested into sickness behaviours, the ability to reproduce should decrease. If the social circumstances were so that animals had no chance of reproducing (for example, no available mates), they should invest in the amount of sickness behaviours that maximizes survival (arrow no. 1). When social circumstances are such that investment in reproduction is possible, the point at which the survival and fecundity curves intersect should dictate the optimal amount of investment in sickness behaviours (arrow no. 2). The behavioural change from arrow 1 to arrow 2 represents the socially induced modulation of sickness behaviours.

2. Behavioural effects of infection

Sickness behaviour is defined as a generalized reduction in the occurrence of an array of behaviours in response to an infection. The changes include reduced food and water intake, reduced activity, reduced engagement in social activities, decreased exploratory behaviour, inability to experience pleasure, decreased libido and increased somnolence (summarized in [8]). Sickness behaviours are widespread in the animal kingdom, occurring in invertebrates [9] and a variety of vertebrates, including amphibians [10], reptiles [11], birds [12] and mammals, notably humans [13].

Importantly, sickness behaviours are not caused by the infectious agent itself, but by the host organism as it responds to this agent via central and peripheral release of cytokines, which include interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor alfa (TNFα) [14] (but see recent report by Chiu et al. [15] on effects of bacteria on pain receptors). Accordingly, administration of IL-1β and TNFα induces sickness behaviours in rodents (reviewed in [16]). Another widely used method to mimic the symptoms of an infection that permits focusing on host-mediated (versus pathogen-mediated) effects on behaviour is via administration of non-pathogenic antigens. One example is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of Gram-negative bacteria cell walls, which induces sickness behaviours by activation of the immune response [17]. The availability of these tools (both cytokines and non-pathogenic antigens) makes the study of sickness behaviour very tractable and easy to implement.

3. Sickness behaviours, plasticity and motivation

Historically, physicians have regarded sickness behaviours as an undesirable side effect of disease (as described in [4]). Hart [3] proposed an alternative view, suggesting that these behaviours consist of a highly organized strategy to aid in fighting the infection, by shifting energy from non-essential activities into the immune system. From this framework, emerges the possibility of a trade-off: the body has limited resources (which could be in the form of energy, nutrients or time) and in order to fight an infection these need to be allocated towards sickness behaviours at the expense of other behaviours. The idea of a trade-off relies on the immune response being costly, and there are currently several lines of evidence for energetic costs of immunity [18–20]. These costs can be converted into reduced growth [21], reproduction [22] and survival [23]. When animals are infected, there should therefore be a region of optimal investment in sickness behaviours that maximizes lifetime reproductive success. The ability of individuals to modify their behaviour according to different environmental conditions (i.e. to exhibit behavioural plasticity) should be of great importance in balancing the costs and benefits of this trade-off.

Early studies by Miller [24] suggested that sickness behaviours could be considered a motivational state. In Miller's initial experiment, he demonstrated that when undergoing an endotoxin challenge, rats had higher motivation to rest than to receive rewards or avoid electrical stimulation. This observation indicates that, when sick, animals reorganize their priorities and are able to adjust behaviours in a way that benefits their recovery from infection. This reorganization may become more complex when infected animals are simultaneously faced with numerous competing factors, which probably happens in their natural environment. Since the initial motivational approach, several studies have shown that a variety of factors can affect the extent to which sickness behaviours are expressed, including abiotic factors such as season (e.g. [25–27]) and biotic factors such as the animal's sex [28–30].

4. Social context: a potent modulator of sickness behaviours

An animal's social context encompasses many factors that have the potential to interact to impact the motivation to engage in sickness behaviours. Social behaviour is defined here as behaviours expressed towards conspecifics that benefit one or more individuals in the group and social context as the social setting (including social structure of the group and social roles within it) in which these behaviours take place (sensu [31]; also see [32]). Because social context is a main determinant of the costs and benefits associated with investment into survival versus reproduction, it should greatly affect the amount of investment in sickness behaviours (figure 1). Considering the importance for fitness of fine-tuning behavioural expression to changes in social environment [33], the terminal investment hypothesis [34] would suggest that these types of behavioural adjustments should be even more critical during an infection when animals experience deteriorating physical conditions. In the following sections, I briefly review the most studied social contexts that can affect the expression of sickness behaviours (table 1).

Table 1.

Keynote studies demonstrating an effect of social context on sickness behaviours (SB), induced either through exposure to LPS or cytokine.

| context | taxa | effects of social environment on SB (ref.) |

|---|---|---|

| presence of mates | Rattus novergicus (rat) | sexual behaviour of males remains elevated, even while activity levels are reduced [28] |

| Taeniopygia guttata (zebra finch) | activity of males is increased [35] | |

| Mus musculus (mouse) | increased depressive-like symptoms in males [36] | |

| presence of offspring | Mus musculus (mouse) | maternal behaviour is partially restored at low temperatures [37] |

| Mus musculus (mouse) | maternal aggression remains high when intruder is present [38] | |

| Passer domesticus (house sparrow) | effect on nest desertion decreases with increased brood size [22] | |

| presence of mother | Cavia porcellus (guinea pig) | male pups decreased SB when reunited with mother [39] |

| early social isolation | Sus domesticus (domestic pig) | increased SB later in life [40] |

| Mus musculus (mouse) | stronger and longer-lasting symptoms of SB later in life [41,42] | |

| presence of intruder | Melospiza melodia (song sparrow) | effect on territorial aggression is reduced during breeding season [27] |

| Macaca mulatta (Rhesus monkeys) | reduced somnolence [43] | |

| group housing | Mus musculus (mouse) | subordinate male mice show increased defensive and social exploratory behaviours [44] |

| Taeniopygia guttata (zebra finch) | decreased SB in males [45] | |

| Rattus novergicus (rat) | decreased SB in males, increased in females [46] |

(a). Mating

Mating behaviour has obvious implications for fitness when it leads to production of offspring. In the context of mating, males and females should generally have different motivations to modulate their investment in sickness behaviours. While for both sexes, investment in sickness behaviours may lead to increased lifetime fitness by increasing the likelihood of survival to the next season, males that suppress symptoms of infection when presented with the chance to mate will probably gain an immediate fitness advantage, especially if mating opportunities are limited. By contrast, females that decrease mating behaviour when ill are reducing the risk of spontaneous abortion of the fetus during infection [47], thereby minimizing fitness losses. One example of the effect of social context on sickness behaviour is the study carried out by Yirmiya et al. [28] demonstrating that, when presented with a mate, male rats are less sensitive to the effects of IL-1β on mating behaviour than female rats. There is also indication that immune challenged male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) are affected by the presence of a potent sexual stimulus. When presented with a novel female, animals suffering from a simulated acute infection were able to not only behave similarly to control-injected birds, but also to activate their reproductive axis and to court females to the same extent as the controls [35]. However, experiments in male mice show an almost opposite effect, with an increase in depressive-like behaviours when presented with a receptive female, as compared to control males kept in isolation, as well as elimination of mating behaviour, as compared to control-injected mice [36]. More studies focusing on species with different reproductive strategies are necessary to fully understand the extent and direction of behavioural modulation. The challenge will be predicting how different diseases alter the trade-off between current and future reproduction and how the social environment impacts this trade-off. One intriguing comparison would be of sickness behaviours of closely related species of semelparous (species that breed only once in their lifetime) and iteraparous (species able to breed more than once in their lifetime) animals. Given such a concentrated effort in reproduction, do semelparous species even display sickness behaviours during the breeding season? One informative type of study contrasts the same species living under different environmental conditions that modify the costs and benefits of foregoing mating under infection. For example, song sparrow (Melospiza melodia) populations at low latitudes have a longer breeding season than their higher latitude counterparts and, thus, animals of low-latitude populations should be able to invest more in recovering from infection during this season. Indeed, birds from a population at lower latitude had more intense and longer lasting sickness behaviours (assessed by activity obtained via radiotelemetry) after an LPS injection than those from the higher latitude population [48]. Since these differences could be owing to other factors, such as immediate environmental differences (e.g. temperature), Adelman et al. [49] also tested animals from the two populations in a common environment under controlled laboratory conditions. They found that the behavioural differences between the populations are maintained in captivity, which points to additional factors in explaining this variation (such as genetic or maternal effects, for example).

(b). Parental care

In many taxa, postpartum parental care is essential to survival of offspring. A number of experiments suggest that the drive for parental care partially trumps infection symptoms. Aubert et al. [37] demonstrated that in conditions which place the survival of the offspring at risk, maternal care overcomes sickness behaviour. Specifically, when female mice injected with LPS and their litters where housed at different room temperatures, nest building in LPS-injected dams was reduced at room temperature (20°C), but not at critically low temperatures (6°C). It is a common behaviour in rodents for lactating females to display aggression towards intruders, given the likelihood of infanticide. Weil et al. [38] demonstrated that in mice, maternal aggression towards a virgin male intruder was not changed by an LPS injection at a dose sufficient to induce classical components of sickness behaviour (such as reduced food intake). Both of these experiments show that the expression of sickness behaviour is reduced in situations where maternal care is more critical for pup survival. To optimize fitness benefits, female investment in sickness behaviours should be higher before mating, since disease can increase chances of spontaneous abortion or damage to offspring (reviewed in [47,50]), while during parental care, sickness behaviours should be decreased if this allows for greater expression of care essential for offspring survival. This is especially true for mammals, in which offspring are more dependent on post-natal maternal care (through lactation). Animals that maintain food supplies (e.g. hoarders) can engage in sickness behaviours while still investing in future needs. Siberian hamsters subjected to an LPS injection reduce food intake but maintain hoarding behaviour [51]. Since male, but not female, Siberian hamsters showed a trend towards decreasing hoarding, the authors suggested that females might behave this way to alleviate the energetic costs of lactation in the future. Exposure to endotoxin seems thus more effective in suppressing the immediate response to food than the anticipatory response to future needs.

There is evidence that the amount of investment in parental care during disease also depends on the potential fitness gain of the current reproductive bout. In a study of house sparrows, the likelihood of a female abandoning the nest after an LPS injection diminished with brood size [22]. In non-mammalian species with bi-parental care (many birds, for example), sickness behaviours of both sexes should be affected to the same extent since both parents contribute the same type of resources and are equally important to ensure offspring survival. Of course, additional factors might interact to affect modulation of sickness in this scenario, as for example, the opportunity for extra pair copulations, which might bias one of the parents to being more prone to obscuring symptoms of sickness. Experiments specifically addressing how different forms of care contribute to modulation of sickness behaviours have yet to be carried out, even though there is the suggestion that sickness behaviours are differentially affected in species with different types of parental care. For example, while IL-1β administration to females of a uniparental (female-only) rodent species (Mus musculus) inhibited sexual behaviour and eliminated the expected preference to mate with intact versus castrated males [29], LPS injection of females of a biparental rodent species (Microtus ochrogaster) enhanced partner preference of familiar versus unfamiliar males and facilitated pair bonding [52]. These differences might suggest that while females of species with biparental care can afford to invest in reproduction while sick, given the paternal contribution to care, the opposite behaviour might be adaptive for females that receive no help from males in caring for offspring. Indeed, male house sparrows show increased paternal effort (feeding rate) when their mates reduce feeding effort owing to an LPS injection [22]. By exposing closely related species to a simulated infection, we may reveal the conditions that promoted differences in behavioural strategies. Social modulation of sickness behaviours can thus provide a paradigm for studying the motivations underlying social behaviours with implications for mate choice and sexual selection theory.

(c). Early social environment

Sickness behaviours are affected on both ends of the parental care dyad: from the parental side (as described above) and from the offspring side. When guinea pig pups are isolated and injected with LPS and later reunited with the mother, only the behaviour of male pups is ameliorated [39]. This study once again emphasizes sex differences in social modulation of sickness behaviours. Early social environment can also influence sickness responses later in life. In a study by Tuchscherer et al. [40], domestic piglets were exposed on a daily basis to 2 h of social isolation from ages 3 to 11 days. When their response to an LPS injection 45 days after isolation was measured, the animals subjected to isolation demonstrated a significantly higher vomiting response then control animals. A similar effect was found for mouse pups separated from their dams [41]. More recently, Avitsur et al. [42] showed that early age separation of mouse pups from the dams altered the proinflammatory response to endotoxin administration later in life and that these alterations seem to be sex-specific. While it might be challenging to account for in field studies, in the laboratory it may be relevant to consider early rearing environment when examining adult immune responses.

(d). Agonistic interactions: territorial intrusions and social status

Animals that are able to hold high-quality territories can have fitness advantages in several ways, for example, by having access to better food sources, better nest sites and better mates. In fact, only territorial males are able to mate in many passerine species. Song sparrows (Melospiza melodia morphna) are territorial all year round. Nevertheless, the response of male song sparrows to an LPS injection is dependent on season. Injected males reduce territorial aggression towards conspecifics during the non-breeding season, but show low responsiveness to the same dose of LPS in the early breeding phase, when territorial defence dictates reproductive success [27]. A similar effect occurs in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), where the effects of somnolence induced by administration of IL-1 are abolished by the presence of an intruder in the enclosure [43]. Interestingly, in contrast to the social withdrawal that is typically observed in many rodents as a result of an LPS injection [14,16], rhesus monkeys display greater affiliation towards conspecifics [53]. This illustration of species-specific differences of selected aspects of sickness behaviours should encourage comparative studies that can help us understand how different aspects of sickness behaviours are regulated. One complicating factor that should be emphasized is that even for what may initially seem similar manipulations, like group versus isolation housing, very different demands are imposed onto the individual depending on its social structure. For example, while male rats are able to cohabit at high densities without great manifestations of aggression, group-housing can be extremely stressful for certain species of mice, in which hierarchies need to be established and maintained often through aggressive interactions.

Social rank has been shown to affect physiology and health in several taxa, including primates [54], but its link to modulation of sickness behaviour is less well understood. However, studies of male mice indicate that social position in a hierarchy differentially affects the expression of sickness behaviours. Dominant male mice injected with LPS showed reductions in activity and aggression, whereas submissive males exhibited increases in both defensive and social exploratory behaviours [44]. Hence, it seems that higher social ranking is affording the dominant males the possibility to focus on recovering from an infection, whereas submissive males still need to display defensive behaviours. In zebra finches, group-housing (versus housing in isolation) is associated with reduced expression of sickness behaviour without significant alteration of the inflammatory response as quantified by plasma IL-6 [45], which could be an indication that in certain social contexts animals have some motivation to conceal their sickness, for example, to maintain social status. In male rats, group-housing also attenuates LPS-induced sickness behaviours, whereas in females, group-housing exacerbates these behaviours relative to LPS-injected animals housed in isolation [46]. In an experiment using house finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), infection with the bacterium Mycoplasma gallisepticum caused individuals to become more submissive (i.e. less aggressive). The alteration in behaviour of the sick bird in turn caused healthy conspecifics to increase their proximity to these individuals, as they were found more frequently feeding near them [55]. Changes in behaviour of both the infected and non-infected individuals could therefore have important impacts on disease transmission rates. Indeed, it was recently shown that in wild deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) behavioural phenotype is associated with infection status [56]: bold mice had three times the likelihood of being infected with Sin Nombre Virus than did shy mice. While the authors cannot determine with certainty whether the infection is a cause or a consequence of the behaviours, this study alerts for the importance of behavioural heterogeneity for disease transmission.

5. Costs to suppressing sickness behaviours

The ability to modulate sickness symptoms according to the social context could prove adaptive in the sense that it might allow the animals to keep their social position in the group, preserve mating opportunities and increase the survival of offspring. But on the other hand, not giving the body the opportunity to fight the infection could have damaging effects on health. While several studies have focused on testing whether mounting an immune response is costly, fewer studies exist on the consequences of supressing the immune response, specifically concerning the behavioural part of this response. One classic example of costs of not engaging in a behavioural response associated with infection comes from experiments with ectotherms prevented from developing a behavioural fever (lizards: [57], fish: [58]). These animals suffered from higher mortality than animals that were able to develop fever. What physiological costs may accompany the socially induced suppression of sickness behaviours? A study by Lopes et al. [59] suggests that zebra finches which spend more time resting also have increased immune defences, as quantified by their ability to develop a fever response, to produce acute phase proteins and to kill bacteria. Understanding the consequences of social suppression of sickness behaviours could be used, for example, to improve welfare of sick animals, and it is thus a theme that warrants further exploration.

When sickness behaviours are derived from chronic inflammation, social modulation of sickness may be beneficial. It is known that certain chronic depressive disorders and dysfunctions of the central nervous system can be associated with poorly regulated and prolonged inflammation [17]. Also, sickness behaviours and depression share similar symptoms and, potentially, similar inflammatory pathways [60]. A study of female mice bearing ovarian carcinoma suggested that social housing was able to reduce depressive-like symptoms [61], as quantified by a sucrose intake test. In an experimental model of stroke in rats, social housing (males housed with ovariectomized females) reduced ischaemic damage and mortality through a mechanism that appears to be mediated by changes in the inflammatory response [62]. While this study did not focus on behavioural alterations, it illustrates how for certain diseases social housing might be beneficial. Actions in which increased human contact can be provided for patients with these types of conditions might help ameliorate some of their symptoms.

6. Mediators of social modulation of sickness behaviours

The behavioural expression of disease should ultimately result from a crosstalk between the immune, endocrine and nervous systems. All of these systems are susceptible to being impacted by changes in the social environment. While an in-depth discussion of mechanisms is outside the scope of this review, I pinpoint some potential modulators of sickness behaviours in the context of social interactions. Obvious candidates from the immune system are pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Cytokines can directly impact behaviour [29,63] and a number of experiments have demonstrated an ability of the social environment to alter these [35,36,62]. A recent review by Hennessy et al. [64] explores the potential for cytokines to have social functions in non-infected individuals. Regarding the endocrine system, socially modulated hormones with immunomodulatory actions are likely candidates. The most studied mediators have been testosterone and glucocorticoids. While many studies indicate a suppressive effect of testosterone on the immune system (e.g. [18,65,66] and recently [67]) and even directly on sickness behaviour [68–71], this is not always the case [72–75]. The story is also complex with glucocorticoids. While historically seen as immunosuppressive hormones [54], different lines of evidence indicate that stress can actually potentiate the immune response [76]. Nonetheless, removal of the adrenal glands leads to increased sickness behaviours [77–80], suggesting a role for glucocorticoids in this mediation. Neural transmitters that are relevant for the regulation of social behaviours and also seem to be involved in modulating inflammatory responses, include acetylcholine, serotonin, dopamine and nitric oxide. For a comprehensive review of the bidirectional interaction between the brain and immune system, see [81].

Different modulators might be more relevant depending on the social context being studied. For example, in conditions that are perceived as stressors, such as in the case of isolation housing, maternal separation or territorial intrusion, the main mediator might be a glucocorticoid. By contrast, sex differences in sickness behaviours might be linked more strongly to sex hormones. Thus, to unravel the underlying mediators of the social modulation of the sickness response, it is critical to take careful consideration of the differential load that different social contexts pose on the individual.

7. Implications, directions for future research and conclusion

The study of the modulation of sickness behaviours lies at the intersection of several fields (behavioural ecology, immunology, neuroendocrinology, psychology, evolution, animal welfare, veterinary and human medicine), providing a new platform to study behaviour from diverse angles. Experiments using immune challenges to examine the flexibility of the immune response under different circumstances are contributing to advancing the understanding of life-history evolution [48], as well as untangling the relative contributions of non-genetic (including, for example, ecological as well as maternal effects) and genetic factors towards the observed differences in behaviour during infection [49,82]. For example, recent studies are helping to shape models of the terminal investment hypothesis [83]. The growing interest in the ecological aspects of disease is reflected by the recent creation of a Division of Ecological Immunology and Disease Ecology within the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology, and a Disease and Host–Parasite Ecology Section within the Ecological Society of America.

Since the findings summarized here demonstrate that expression of sickness behaviour can be modified in certain social circumstances, we should be aware of instances where we might not be able to identify sick animals. Early detection of diseased animals should help prevent disease spread and prove relevant in a world where infectious diseases cause a major burden in terms of both lives lost and economic damage [84]. Comparative studies leading to an improved understanding of the significance of social context for different animals should facilitate our ability to predict species-specific sickness behaviours and the social cues leading to changes in these behaviours. This knowledge can then be used to determine the species and circumstances in which we can detect sickness behaviourally and the ones for which additional tools are necessary, in order to, for example, guarantee food safety and avoid spread of diseases within animal facilities.

The literature reviewed highlights the great plasticity of the sickness behaviour response in the face of social stimuli. However, we have limited understanding of the physiological consequences for the host in diminishing investment in sickness behaviours and further investigation is necessary. When making decisions regarding when to allow and when to try to suppress sickness behaviours, veterinarians, doctors and animal facility managers must weigh these costs against the potential for pain or suffering induced by the disease. If social housing can ameliorate the symptoms of non-communicable diseases with little cost to the host, then we might be easily able to increase wellness of captive animals suffering from disease.

Understanding how, when and why social modulation of sickness behaviours occurs will not only advance our knowledge of life-history evolution and the motivation for engaging in social behaviours, but also translate into better prevention strategies for infectious disease spread and improved tools to ameliorate symptoms of infection and depression. The increased connectivity of animal populations (including humans) has led to an unprecedented potential for disease pandemics. It will take concentrated and transdisciplinary efforts to understand and address these problems. In doing so, we would be wise to consider the role of social context in the modulation of sickness behaviours.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for comments provided by Gregory R. Goldsmith, Manuela Ferrari, Eileen A. Lacey, Samuel L. Diaz-Muñoz, Tobias Uller, Jim S. Adelman, Noah T. Ashley and George E. Bentley. Finally, I thank Barbara König and Andri Manser for discussions on figure 1.

Funding statement

I thank the Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Zurich for financial support through a post-doctoral research position.

References

- 1.Ortega y Gasset J. 1914. Meditaciones del Quijote. Serie II, vol, p. 43 Madrid, Spain: Publicaciones de la Residencia de Estudiantes. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kluger MJ. 1986. Is fever beneficial. Yale J. Biol. Med. 59, 89–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart BL. 1988. Biological basis of the behavior of sick animals. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 12, 123–137. ( 10.1016/S0149-7634(88)80004-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson RW. 2002. The concept of sickness behavior: a brief chronological account of four key discoveries. Vet. Immunol. Immunop. 87, 443–450. ( 10.1016/S0165-2427(02)00069-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Exton MS. 1997. Infection-induced anorexia: active host defence strategy. Appetite 29, 369–383. ( 10.1006/appe.1997.0116) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grieger TA, Kluger MJ. 1978. Fever and survival: the role of serum iron. J. Physiol. 279, 187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray MJ, Murray AB. 1979. Anorexia of infection as a mechanism of host defense. Am. J. Cli. Nutr. 32, 593–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashley NT, Wingfield JC. 2012. Sickness behavior in vertebrates: allostasis, life history modulation and hormonal regulation. In Ecoimmunology (eds Nelson RJ, Demas GE.), pp. 45–91. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamo SA. 2006. Comparative psychoneuroimmunology: evidence from the insects. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 5, 128–140. ( 10.1177/1534582306289580) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llewellyn D, Brown GP, Thompson MB, Shine R. 2011. Behavioral responses to immune-system activation in an anuran (the cane toad, Bufo marinus): field and laboratory studies. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 84, 77–86. ( 10.1086/657609) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deen CM, Hutchison VH. 2001. Effects of lipopolysaccharide and acclimation temperature on induced behavioral fever in juvenile Iguana iguana. J. Therm. Biol. 26, 55–63. ( 10.1016/S0306-4565(00)00026-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson RW, Curtis SE, Dantzer R, Bahr JM, Kelley KW. 1993. Sickness behavior in birds caused by peripheral or central injection of endotoxin. Physiol. Behav. 53, 343–348. ( 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90215-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollmer-Conna U, et al. 2004. Production of pro-inflammatory cytokines correlates with the symptoms of acute sickness behaviour in humans. Psychol. Med. 34, 1289–1297. ( 10.1017/S0033291704001953) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kent S, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R, Hardwick AJ, Kelley KW, Rothwell NJ, Vannice JL. 1992. Different receptor mechanisms mediate the pyrogenic and behavioral-effects of interleukin-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 9117–9120. ( 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu IM, et al. 2013. Bacteria activate sensory neurons that modulate pain and inflammation. Nature 501, 52–57. ( 10.1038/nature12479) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dantzer R. 2004. Cytokine-induced sickness behaviour: a neuroimmune response to activation of innate immunity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 500, 399–411. ( 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.040) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. 2008. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 46–57. ( 10.1038/nrn2297) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson RJ, Demas GE. 1996. Seasonal changes in immune function. Q. Rev. Biol. 71, 511–548. ( 10.1086/419555) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheldon BC, Verhulst S. 1996. Ecological immunology: costly parasite defences and trade-offs in evolutionary ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11, 317–321. ( 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10039-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lochmiller RL, Deerenberg C. 2000. Trade-offs in evolutionary immunology: just what is the cost of immunity? Oikos 88, 87–98. ( 10.1034/J.1600-0706.2000.880110.X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uller T, Isaksson C, Olsson M. 2006. Immune challenge reduces reproductive output and growth in a lizard. Funct. Ecol. 20, 873–879. ( 10.1111/J.1365-2435.2006.01163.X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonneaud C, Mazuc J, Gonzalez G, Haussy C, Chastel O, Faivre B, Sorci G. 2003. Assessing the cost of mounting an immune response. Am. Nat. 161, 367–379. ( 10.1086/346134) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanssen SA, Hasselquist D, Folstad I, Erikstad KE. 2004. Costs of immunity: immune responsiveness reduces survival in a vertebrate. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 925–930. ( 10.1098/rspb.2004.2678) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller NE. 1964. Some psychophysiological studies of motivation and of the behavioral-effects of illness. Bull. Br. Psychol. Soc. 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bilbo SD, Drazen DL, Quan N, He LL, Nelson RJ. 2002. Short day lengths attenuate the symptoms of infection in Siberian hamsters. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 447–454. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1915) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prendergast BJ, Hotchkiss AK, Bilbo SD, Kinsey SG, Nelson RJ. 2003. Photoperiodic adjustments in immune function protect Siberian hamsters from lethal endotoxemia. J. Biol. Rhythm 18, 51–62. ( 10.1177/0748730402239676) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owen-Ashley NT, Wingfield JC. 2006. Seasonal modulation of sickness behavior in free-living northwestern song sparrows (Melospiza melodia morphna). J. Exp. Biol. 209, 3062–3070. ( 10.1242/Jeb.02371) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yirmiya R, Avitsur R, Donchin O, Cohen E. 1995. Interleukin-1 inhibits sexual behavior in female but not in male rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 9, 220–233. ( 10.1006/brbi.1995.1021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avitsur R, Yirmiya R. 1999. The immunobiology of sexual behavior: gender differences in the suppression of sexual activity during illness. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 64, 787–796. ( 10.1016/S0091-3057(99)00165-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owen-Ashley NT, Turner M, Hahn TP, Wingfield JC. 2006. Hormonal, behavioral, and thermoregulatory responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharide in captive and free-living white-crowned sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii). Horm. Behav. 49, 15–29. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.04.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson EO. 1975. Sociobiology. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Székely T, Moore AJ, Komdeur J. 2010. Social behaviour: genes, ecology and evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliveira RF. 2009. Social behavior in context: hormonal modulation of behavioral plasticity and social competence. Integr. Comp. Biol. 49, 423–440. ( 10.1093/Icb/Icp055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams GC. 1966. Natural selection, the costs of reproduction, and a refinement of Lack's principle. Am. Nat. 100, 687–690. ( 10.1086/282461) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lopes PC, Chan H, Demathieu S, Gonzalez-Gomez PL, Wingfield JC, Bentley GE. 2013. The impact of exposure to a novel female on symptoms of infection and on the reproductive axis. Neuroimmunomodulation 20, 348–360. ( 10.1159/000353779) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weil ZM, Bowers SL, Pyter LM, Nelson RJ. 2006. Social interactions alter proinflammatory cytokine gene expression and behavior following endotoxin administration. Brain Behav. Immun. 20, 72–79. ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aubert A, Goodall G, Dantzer R, Gheusi G. 1997. Differential effects of lipopolysaccharide on pup retrieving and nest building in lactating mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 11, 107–118. ( 10.1006/brbi.1997.0485) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weil ZM, Bowers SL, Dow ER, Nelson RJ. 2006. Maternal aggression persists following lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of the immune system. Physiol. Behav. 87, 694–699. ( 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hennessy MB, Deak T, Schiml-Webb PA, Wilson SE, Greenlee TM, McCall E. 2004. Responses of guinea pig pups during isolation in a novel environment may represent stress-induced sickness behaviors. Physiol. Behav. 81, 5–13. ( 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.11.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuchscherer M, Kanitz E, Puppe B, Tuchscherer A. 2006. Early social isolation alters behavioral and physiological responses to an endotoxin challenge in piglets. Horm. Behav. 50, 753–761. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Avitsur R, Sheridan JF. 2009. Neonatal stress modulates sickness behavior. Brain Behav. Immun. 23, 977–985. ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.05.056) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Avitsur R, Maayan R, Weizman A. 2013. Neonatal stress modulates sickness behavior: role for proinflammatory cytokines. J. Neuroimmunol. 257, 59–66. ( 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.02.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedman EM, Reyes TM, Coe CL. 1996. Context-dependent behavioral effects of interleukin-1 in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Psychoneuroendocrinology 21, 455–468. ( 10.1016/0306-4530(96)00010-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohn DWH, de Sa-Rocha LC. 2006. Differential effects of lipopolysaccharide in the social behavior of dominant and submissive mice. Physiol. Behav. 87, 932–937. ( 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.02.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopes PC, Adelman J, Wingfield JC, Bentley GE. 2012. Social context modulates sickness behavior. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 66, 1421–1428. ( 10.1007/S00265-012-1397-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yee JR, Prendergast BJ. 2010. Sex-specific social regulation of inflammatory responses and sickness behaviors. Brain Behav. Immun. 24, 942–951. ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aisemberg J, Vercelli C, Wolfson M, Salazar AI, Osycka-Salut C, Billi S, Ribeiro ML, Farina M, Franchi AM. 2010. Inflammatory agents involved in septic miscarriage. Neuroimmunomodulation 17, 150–152. ( 10.1159/000258710) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adelman JS, Cordoba-Cordoba S, Spoelstra K, Wikelski M, Hau M. 2010. Radiotelemetry reveals variation in fever and sickness behaviours with latitude in a free-living passerine. Funct. Ecol. 24, 813–823. ( 10.1111/J.1365-2435.2010.01702.X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adelman JS, Bentley GE, Wingfield JC, Martin LB, Hau M. 2010. Population differences in fever and sickness behaviors in a wild passerine: a role for cytokines. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 4099–4109. ( 10.1242/jeb.049528) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friebe A, Arck P. 2008. Causes for spontaneous abortion: What the bugs ‘gut’ to do with it? Int. J. Biochem. Cell B 40, 2348–2352. ( 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Durazzo A, Proud L, Demas GE. 2008. Experimentally induced sickness decreases food intake, but not hoarding, in Siberian hamsters (Phodopus sungorus). Behav. Process. 79, 195–198. ( 10.1016/j.beproc.2008.07.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bilbo SD, Klein SL, Devries AC, Nelson RJ. 1999. Lipopolysaccharide facilitates partner preference behaviors in female prairie voles. Physiol. Behav. 68, 151–156. ( 10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00154-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willette AA, Lubach GR, Coe CL. 2007. Environmental context differentially affects behavioral, leukocyte, cortisol, and interleukin-6 responses to low doses of endotoxin in the rhesus monkey. Brain Behav. Immun. 21, 807–815. ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.01.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sapolsky RM. 2005. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science 308, 648–652. ( 10.1126/science.1106477) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bouwman KM, Hawley DM. 2010. Sickness behaviour acting as an evolutionary trap? Male house finches preferentially feed near diseased conspecifics. Biol. Lett. 6, 462–465. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dizney L, Dearing MD. 2013. The role of behavioural heterogeneity on infection patterns: implications for pathogen transmission. Anim. Behav. 86, 911–916. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.08.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kluger MJ, Ringler DH, Anver MR. 1975. Fever and survival. Science 188, 166–168. ( 10.1126/science.1114347) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boltana S, et al. 2013. Behavioural fever is a synergic signal amplifying the innate immune response. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20131381 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.1381) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lopes PC, Springthorpe D, Bentley GE. In press Increased activity correlates with reduced ability to mount immune defenses to endotoxin in zebra finches. J. Exp. Zool. ( 10.1002/jez.1873) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Maes M, Berk M, Goehler L, Song C, Anderson G, Galecki P, Leonard B. 2012. Depression and sickness behavior are Janus-faced responses to shared inflammatory pathways. BMC Med. 10, 66 ( 10.1186/1741-7015-10-66) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamkin DM, Lutgendorf SK, Lubaroff D, Sood AK, Beltz TG, Johnson AK. 2011. Cancer induces inflammation and depressive-like behavior in the mouse: modulation by social housing. Brain Behav. Immun. 25, 555–564. ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karelina K, Norman GJ, Zhang N, Morris JS, Peng HY, DeVries AC. 2009. Social isolation alters neuroinflammatory response to stroke. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 5895–5900. ( 10.1073/pnas.0810737106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Avitsur R, Cohen E, Yirmiya R. 1997. Effects of interleukin-1 on sexual attractivity in a model of sickness behavior. Physiol. Behav. 63, 25–30. ( 10.1016/S0031-9384(97)00381-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hennessy MB, Deak T, Schiml PA. 2014. Sociality and sickness: have cytokines evolved to serve social functions beyond times of pathogen exposure? Brain Behav. Immun. 37, 15–20. ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grossman CJ. 1985. Interactions between the gonadal-steroids and the immune system. Science 227, 257–261. ( 10.1126/science.3871252) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alexander J, Stimson WH. 1988. Sex-hormones and the course of parasitic infection. Parasitol. Today 4, 189–193. ( 10.1016/0169-4758(88)90077-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Furman D, Hejblum BP, Simon N, Jojic V, Dekker CL, Thiebaut R, Tibshirani RJ, Davis MM. 2014. Systems analysis of sex differences reveals an immunosuppressive role for testosterone in the response to influenza vaccination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 869–874. ( 10.1073/pnas.1321060111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dantzer R, Bluthe RM, Kelley KW. 1991. Androgen-dependent vasopressinergic neurotransmission attenuates interleukin-1-induced sickness behavior. Brain Res. 557, 115–120. ( 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90123-D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spinedi E, Suescun MO, Hadid R, Daneva T, Gaillard RC. 1992. Effects of gonadectomy and sex-hormone therapy on the endotoxin-stimulated hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis: evidence for a neuroendocrine-immunological sexual dimorphism. Endocrinology 131, 2430–2436. ( 10.1210/en.131.5.2430) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seale JV, Wood SA, Atkinson HC, Harbuz MS, Lightman SL. 2004. Gonadal steroid replacement reverses gonadectomy-induced changes in the corticosterone pulse profile and stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity of male and female rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 16, 989–998. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01258.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ashley NT, Hays QR, Bentley GE, Wingfield JC. 2009. Testosterone treatment diminishes sickness behavior in male songbirds. Horm. Behav. 56, 169–176. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.04.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bilbo SD, Nelson RJ. 2001. Sex steroid hormones enhance immune function in male and female Siberian hamsters. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 280, R207–R213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hasselquist D, Marsh JA, Sherman PW, Wingfield JC. 1999. Is avian humoral immunocompetence suppressed by testosterone? Behav. Eco.l Sociobiol. 45, 167–175. ( 10.1007/s002650050550) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roberts ML, Buchanan KL, Hasselquist D, Evans MR. 2007. Effects of testosterone and corticosterone on immunocompetence in the zebra finch. Horm. Behav. 51, 126–134. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.09.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prendergast BJ, Baillie SR, Dhabhar FS. 2008. Gonadal hormone-dependent and -independent regulation of immune function by photoperiod in Siberian hamsters. Am. J. Physiol.-Reg. I 294, R384–R392. ( 10.1152/ajpregu.00551.2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Archie EA. 2013. Wound healing in the wild: stress, sociality and energetic costs affect wound healing in natural populations. Parasite Immunol. 35, 374–385. ( 10.1111/Pim.12048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goujon E, Parnet P, Aubert A, Goodall G, Dantzer R. 1995. Corticosterone regulates behavioral-effects of lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-1-beta in mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Reg. I 269, R154–R159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goujon E, Parnet P, Cremona S, Dantzer R. 1995. Endogenous glucocorticoids down-regulate central effects of interleukin-1-beta on body-temperature and behavior in mice. Brain Res. 702, 173–180. ( 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01041-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnson RW, Propes MJ, Shavit Y. 1996. Corticosterone modulates behavioral and metabolic effects of lipopolysaccharide. Am. J. Physiol.-Reg. I 270, R192–R198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pezeshki G, Pohl T, Schobitz B. 1996. Corticosterone controls interleukin-1 beta expression and sickness behavior in the rat. J. Neuroendocrinol. 8, 129–135. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1996.tb00833.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wrona D. 2006. Neural-immune interactions: an integrative view of the bidirectional relationship between the brain and immune systems. J. Neuroimmunol. 172, 38–58. ( 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.10.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bonneaud C, Balenger SL, Russell AF, Zhang JW, Hill GE, Edwards SV. 2011. Rapid evolution of disease resistance is accompanied by functional changes in gene expression in a wild bird. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 7866–7871. ( 10.1073/pnas.1018580108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Javois J. 2013. A two-resource model of terminal investment. Theor. Biosci. 132, 123–132. ( 10.1007/S12064-013-0176-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fuller T, Bensch S, Muller I, Novembre J, Perez-Tris J, Ricklefs RE, Smith TB, Waldenstrom J. 2012. The ecology of emerging infectious diseases in migratory birds: an assessment of the role of climate change and priorities for future research. Ecohealth 9, 80–88. ( 10.1007/S10393-012-0750-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]