Abstract

Bacillus anthracis and other pathogenic Bacillus species form spores that are surrounded by an exosporium, a balloon-like layer that acts as the outer permeability barrier of the spore and contributes to spore survival and virulence. The exosporium consists of a hair-like nap and a paracrystalline basal layer. The filaments of the nap are comprised of trimers of the collagen-like glycoprotein BclA, while the basal layer contains approximately 20 different proteins. One of these proteins, BxpB, forms tight complexes with BclA and is required for attachment of essentially all BclA filaments to the basal layer. Another basal layer protein, ExsB, is required for the stable attachment of the exosporium to the spore. To determine the organization of BclA and BxpB within the exosporium, we used cryo-electron microscopy, cryo-sectioning and crystallographic analysis of negatively stained exosporium fragments to compare wildtype spores and mutant spores lacking BclA, BxpB or ExsB (ΔbclA, ΔbxpB and ΔexsB spores, respectively). The trimeric BclA filaments are attached to basal layer surface protrusions that appear to be trimers of BxpB. The protrusions interact with a crystalline layer of hexagonal subunits formed by other basal layer proteins. Although ΔbxpB spores retain the hexagonal subunits, the basal layer is not organized with crystalline order and lacks basal layer protrusions and most BclA filaments, indicating a central role for BxpB in exosporium organization.

Keywords: anthrax spores, bacterial ultrastructure, sporulation, cryo-electron microscopy, cryo-sectioning, Tokuyasu technique, 2D crystallography

1. Introduction

Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax, is a highly pathogenic Gram-positive soil bacterium that is also considered a serious threat as an agent of bioterrorism (Ingelsby et al., 1999; Mock and Fouet, 2001). Upon starvation, B. anthracis forms protective spores, which are the primary pathogenic agents, easily spread and highly resistant to environmental stress or prolonged periods (Cano and Borucki, 1995; Nicholson et al., 2000). Spores that enter the body through skin lesions, by ingestion or through inhalation may migrate to the lymph nodes where they germinate and undergo vegetative growth (Dixon et al., 2000; Guidi-Rontani et al., 2001; Guidi-Rontani and Mock, 2002; Cleret et al., 2007). Production of the tripartite anthrax toxin (Ascenzi et al., 2002) in the vegetative cell leads to systemic bacteremia and toxemia, conditions that are often fatal (Moayeri and Leppla, 2004). Growing B. anthracis cells are surrounded by a capsule that prevents phagocytosis and is essential for survival in an infected host (Green et al., 1985).

The B. anthracis spore is a complex, multilayered structure (Gerhardt and Ribi, 1964; Beaman et al., 1972). The nucleoid-containing core is enclosed within a peptidoglycan cortex, which is surrounded by the spore coat (Henriques and Moran, 2007). For many Bacillus species, such as B. subtilis, the coat constitutes the outermost layer of the mature spore (McKenney et al., 2013). However, for B. anthracis and other closely related pathogenic species, such as B. cereus and B. thuringiensis, the spore is encircled by an additional, loosely fitting layer called the exosporium (Gerhardt and Ribi, 1964; Beaman et al., 1972). The exosporium is the major source of spore antigens and serves as the primary permeability barrier of the spore (Swiecki et al., 2006). Although the role of the exosporium in anthrax is controversial (Bozue et al., 2007; Giorno et al., 2007), it appears to play a role in defining spore virulence in its natural soil environment (Williams et al., 2013). The exosporium is also required for spore survival in macrophages (Kang et al., 2005; Basu et al., 2007; Weaver et al., 2007) and for targeting of the spores to phagocytic carrier cells, which serves as the initial step in a productive infection (Oliva et al., 2008). These functions might be especially important when the number of infecting spores is low, a situation likely to occur in nature and upon intentional release of spores.

The exosporium contains approximately 20 different proteins (Steichen et al., 2003; Redmond et al., 2004; Steichen et al., 2005) and is composed of a paracrystalline basal layer and an external hair-like nap (Gerhardt and Ribi, 1964). The filaments of the nap are formed by trimers of the fibrous glycoprotein BclA (Sylvestre et al., 2002; Steichen et al., 2003; Boydston et al., 2005). BclA is attached to the underlying basal layer by its N-terminal domain (Boydston et al., 2005; Thompson and Stewart, 2008), which is followed by an extensively glycosylated collagen-like central region (Daubenspeck et al., 2004), and a C-terminal globular βjellyroll domain that promotes trimer formation (Boydston et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2008). The attachment of nearly all BclA trimers requires the basal layer protein BxpB (also called ExsFA) (Steichen et al., 2005; Sylvestre et al., 2005); residual attachment of BclA requires the BxpB paralog ExsFB (Sylvestre et al., 2005). BclA and BxpB form high molecular mass complexes, which are stable under conditions that normally disrupt non-covalent interactions and disulfide bonds (Steichen et al., 2005; Tan and Turnbough, 2010). Another basal layer component, the highly phosphorylated ExsB protein, is required for the stable attachment of the exosporium to the underlying spore structure (McPherson et al., 2010). Mutant spores lacking ExsB form an exosporium that is easily sloughed when the spores are grown in liquid medium. When spores germinate, the outgrowing cell emerges though a “cap” structure at one end of the exosporium, which appears to result from discontinuous assembly and non-uniform distribution of exosporium structural proteins (Steichen et al., 2007).

Previous studies of plastic-embedded, thin-sectioned B. anthracis spores have shown the overall organization of the exosporium and the layered nature of the spore (Gerhardt and Ribi, 1964; Turnbough, 2003). However, traditional preparation methods do not adequately preserve the ultrastructure of the exosporium and suffer artifacts and distortions due to dehydration and extensive mass loss. More recently, CEMOVIS (cryo-EM of vitreous sections) was used to image frozen-hydrated sections of spores (although even in this case chemical fixation of the spore was necessary) and showed clearly the multilayered organization of the spore (Couture-Tosi et al., 2010). Studies of negatively stained and unstained crystalline layers isolated from disrupted spores have also shown the crystalline nature of some of the layers (Ball et al., 2008; Kailas et al., 2011). However, many questions remain: What proteins are required for the structural integrity of the exosporium? What proteins comprise the crystalline layers? How are the major structural proteins distributed within the exosporium? What are the roles of BclA and BxpB in organizing the exosporium and how are these two proteins connected?

In this study, we have used cryo-electron microscopy of intact, fully hydrated spores (Dubochet et al., 1983; Dubochet et al., 1988) in combination with ultrathin cryo-sectioning (Tokuyasu method)(Tokuyasu, 1973) and two-dimensional (2D) crystallographic analysis of wildtype and mutant B. anthracis spores, to gain a better understanding of the organization of BclA and BxpB in the exosporium. Our results show that trimeric BclA filaments are connected to basal layer protrusions apparently formed by BxpB trimers and that these protrusions interact with an underlying crystalline layer of hexagonal subunits presumably formed by other basal layer proteins. Spores lacking BxpB retain an intact basal layer; however, this layer lacks the BclA-connecting protrusions and crystalline organization, indicating an important role for BxpB in exosporium assembly.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample preparation

B. anthracis Sterne spores were prepared by growing cells at 37°C in liquid Difco sporulation medium until sporulation was complete (Nicholson and Setlow, 1990), with the exception of ΔexsB spores, for which cells were grown on solid medium (McPherson et al., 2010). Spores were collected by centrifugation, washed with water at 4 °C and sedimented through a 20% and 50% Renografin (Bracco Diagnostics, NJ) step gradient (Henriques and Moran, 2000; Steichen et al., 2003). Spores were collected, washed and resuspended in water at a concentration of ≈109 spores/ml.

B. anthracis mutants in which the bclA, bxpB or exsB gene had been deleted (ΔbclA, ΔbxpB and ΔexsB, respectively) were made by allelic exchange methods as previously described (Dai et al., 1995; Daubenspeck et al., 2004). Mutant spores were prepared as described above.

Isolated wildtype and mutant exosporium fragments were prepared by passing spores through a French press at high pressure, followed by purification of the fragments by differential centrifugation, as previously described (Steichen et al., 2003).

2.2. Cryo-electron microscopy

For cryo-EM, 3 μl of spore suspension at a concentration of 108–109 spores/ml were applied to 200 mesh Quantifoil R 2/1 grids pre-washed with chloroform and ethanol, blotted briefly and plunged into liquid ethane, as previously described (Dokland and Ng, 2006). The frozen grids were transferred to a Gatan 622 cryo-holder and observed in an FEI Tecnai F20 electron microscope operated at 200 kV with typical magnifications from 32,500× to 65,500× and defocus settings of 4–8 μm. Images were collected under low-dose conditions on a Gatan Ultrascan 4000 CCD camera.

2.3. Ultrathin cryo-sectioning

Samples were prepared for ultrathin cryo-sectioning according to a modified Tokuyasu protocol (Tokuyasu, 1973; Dokland and Ng, 2006). Spores were pelleted at 2,000×g followed by 1 hr fixation in 3% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde. The pellets were washed with 1× PBS and cryo-protected for 12 hrs at 4°C in 2.3M sucrose in PBS. 6 μl of the sample solution was applied to an aluminum pin and frozen in the cryo-chamber at −80°C. The frozen sample was smoothed and shaped using a cryo-trim 45 diamond knife (Diatome) at −80°C in a Leica Ultracut UC6 microtome. 100 nm sections were cut with a cryo-immuno diamond knife (Diatome) at −120°C. The frozen sections were either dry transferred to glow-discharged 400 mesh carbon only grids or transferred using a droplet of 2% methyl cellulose:2.3M sucrose (1:1) in a wire loop, followed by washing in water and staining with 1% uranyl acetate. No methylcellulose embedding was used.

2.4. Negatively stained samples

Purified exosporium fragments samples were placed on glow-discharged 400 mesh carbon grids and stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Negatively stained samples were observed by conventional methods in an FEI Tecnai F20 electron microscope operated at 200 kV. For cryo-sections, typical magnifications of 32,500× to 65,500× were used, while the exosporium fragments were imaged at a magnification of 81,200× under low-dose conditions and defocus settings ranging from 600 to 2,900 nm.

2.5. Image processing

2D crystallographic processing of the exosporium fragment images was done using the program 2dx (Gipson et al., 2007). The data was processed with CTF correction and p6 symmetry imposed (overall symmetry phase residuals per image ranged from 7.0° to 25.7° to 10Å resolution). The wildtype and ΔbclA data sets included data from at least five separate images, with merging phase residuals of 27.9° and 20.1°, respectively. (For ΔbxpB samples, only one image could be indexed.) The final maps were calculated to 16Å resolution. Difference maps were calculated using CCP4 (CCP4, 1994) by real-space subtraction after normalizing map densities to an average of 0.0 and standard deviation of 1.0. Difference maps were plotted on the same scale as the starting maps. Other image processing and measurements were performed using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012). Periodicities were identified and measured from the power spectra.

3. Results

3.1. The exosporium of wildtype B. anthracis spores

Spores of the Sterne strain of B. anthracis were produced and purified by established procedures (Nicholson and Setlow, 1990; Steichen et al., 2003) and prepared for cryo-EM as previously described (Dokland and Ng, 2006). The Sterne strain is not a human pathogen due to the lack of the vegetative cell capsule (Green et al., 1985), but it produces spores that are essentially identical to those formed by virulent strains (Redmond et al., 2004). Using cryo-EM, the unfixed and unstained spores remain fully hydrated and undistorted (Fig. 1A). Including the balloon-like exosporium, the spores are 1.91±0.18 μm (average ± standard deviation) in length and 1.28±0.15 μm in width. Excluding the exosporium, the spores have average length and width of 1.55±0.20 μm and 0.91±0.01 μm, respectively. The irregularly shaped exosporium has numerous folds and creases and is separated from the more electron-dense underlying spore components by up to 500 nm in some places. In other areas, the exosporium closely approaches the coat. The nap forms a dense, continuous lawn of filaments with an inter-filament spacing of about 7 nm and average length of 68.5±2.7 nm, somewhat longer than the previously reported 61 nm length from negatively stained samples of Sterne spores (Sylvestre et al., 2003). The basal layer is about 12–16 nm thick and is traversed by elongated densities spaced with a periodicity of 7 nm, the same as the nap filaments (Fig. 1C). Viewed perpendicular to its surface, the exosporium exhibits a punctate pattern with similar spacing, presumably corresponding to the densities in the cross-striation (Fig. 1C).

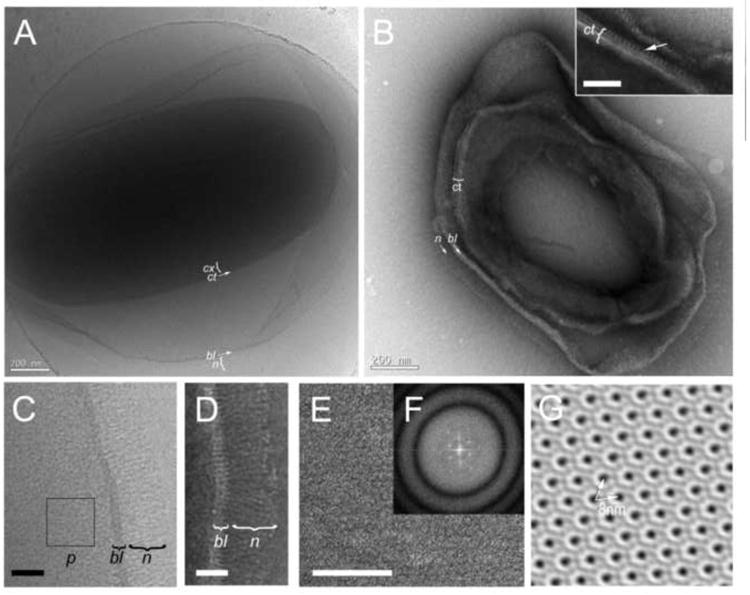

Figure 1.

Electron microscopy of the wildtype B. anthracis spore. (A) Cryo-EM of a frozen-hydrated, intact spore. (B) Negatively stained cryo-section (Tokuyasu method). Scale bars are 200 nm. The basal layer (bl), nap (n), coat (ct) and cortex (cx) are indicated. The inset shows a closeup view of the periodic outer layer (arrow) in the coat. Scale bar = 50 nm. (C) Detail of the wildtype exosporium by cryo-EM. The punctate pattern (p) is indicated. (D) Detail of the ultrathin cryo-section, showing the striated basal layer (bl) and nap filaments (n) with terminal knobs. (E) Part of a negatively stained cryo-section showing an exosporium flat in the plane of the grid. The hexagonal paracrystalline pattern is clearly evident. (F) Power spectrum of the Fourier transform of (E), showing diffraction maxima corresponding to the crystal array. Panel (G) is derived from (E) by 2D crystal processing, without the application of symmetry. The 8 nm lattice spacing is indicated (arrows). Scale bars in C, D and E are 50 nm.

The thickness and density of the spore makes it difficult to distinguish interior features. Nevertheless, a 20-25 nm thick coat with an electron-dense, laminar appearance and the underlying lower-density cortex (40-70nm) can be discerned (Fig. 1A). The cortex is delimited on its inside by a diffuse dark layer that presumably represents the cell membrane.

To examine the exosporium in more detail, ultrathin cryo-sectioning was done according to a modified Tokuyasu protocol (Tokuyasu, 1973; Dokland and Ng, 2006). While this procedure does not preserve the overall integrity of the spore like cryo-EM does, it helps visualize the fine structure of several spore components, including the internal layers. Previous studies on frozen, fully hydrated cryo-sections of B. anthracis and B. cereus spores showed that mild chemical fixation did not cause detectable changes in ultrastructure (Couture-Tosi et al., 2010).

In images of cryo-sections, the nap filaments can be clearly discerned (Fig. 1B). The filaments have an apparent length of around 60 nm, shorter than that observed by cryo-EM, presumably due to shrinkage upon dehydration and staining. Each filament has a terminal knob, about 6 nm in diameter, roughly equal to the reported size of the 40-kDa trimer of the C-terminal domain of BclA (Rety et al., 2005), indicating that each filament is composed of a single BclA trimer (Fig. 1D). The basal layer appears to consist of two sublayers, each about 5 nm wide, separated by a 3–5 nm space. As in the frozen-hydrated samples, the basal layer is spanned by elongated densities with a periodicity of 7 nm, some of which are continuous with the nap filaments (Fig. 1D). Viewed perpendicular to the surface of the exosporium, the basal layer has an obvious crystalline nature with apparent hexagonal symmetry (Fig. 1E). Fourier analysis of this layer shows peaks consistent with a primary lattice spacing of about 8 nm (Fig. 1F). 2D crystal reconstruction without the application of any symmetry reveals a roughly hexagonal pattern of holes (dark staining) surrounded by rings of density (corresponding to protein)(Fig. 1G). The observed deviation from perfect hexagonal symmetry is probably due to distortions during sectioning or lack of planarity of the grid, which would lead to a compression of the hexagonal dimensions in one direction. The hexagonal layer appears to be the same as the type II layer previously observed in the exosporium of B. cereus, B. thuringiensis and B. anthracis spores (Ball et al., 2008; Kailas et al., 2011). The same studies also identified a weakly staining, trigonal “parasporal” layer with 6.5 nm spacing in purified spores of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis, but not in B. anthracis (Ball et al., 2008; Kailas et al., 2011). We also did not observe this layer in our samples.

The coat is also clearly visualized in the sections and can be seen to consist of several lamina, the outermost having a striated appearance, indicative of a periodic lattice with 9–10 nm spacing (Fig. 1B, inset), similar to that previously observed by Couture-Tosi et al. (2010).

3.2. Analysis of mutant spores lacking BclA, BxpB or ExsB

We also analyzed spores lacking BclA, BxpB or ExsB (ΔbclA, ΔbxpB and ΔexsB spores, respectively) by cryo-EM and ultrathin cryo-sectioning. Both approaches showed that ΔbclA spores are similar to the wildtype, but are devoid of nap (Fig. 2A, B), indicating that all detectable filaments are made up of BclA. The exosporium basal layer appears otherwise normal, and the same cross-striation that was seen in the wildtype spores is present (Fig. 2C, D). The basal layer striations terminate in protrusions that extend about 3 nm above the plane of the outer sublayer (Fig. 2D). These protrusions appear to be the sites of attachment of BclA filaments in wildtype spores. Evidently, these protrusions are comprised of BxpB, which is required for attachment of and forms tight complexes with BclA (Steichen et al., 2005; Sylveste et al., 2005).

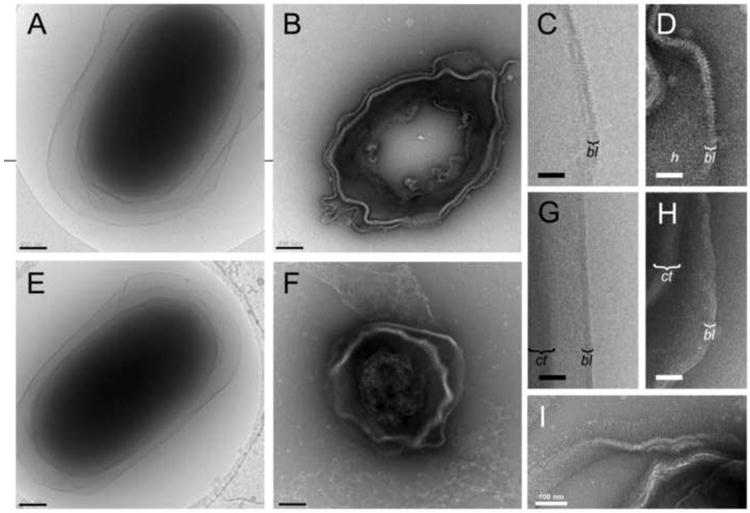

Figure 2.

Electron microscopy of mutant B. anthracis spores. (A) Cryo-EM and (B) negatively stained, ultrathin cryo-section of the ΔbclA spore. Detail view of the ΔbclA exosporium by cryo-EM (C) and cryo-sectioning (D). The basal layer (bl) and the hexagonal pattern (h) are indicated. (E) Cryo-EM and (F) ultrathin cryo-section of the ΔbxpB spore. Detail of the ΔbxpB exosporium by cryo-EM (G) and cryo-sectioning (H). The coat (ct) and basal layer (bl) are indicated. (I) Cryo-section of the ΔexsB spore. Scale bars in A, B, E and F are 200 nm; in C, D, G and H, 50 nm; and in I, 100 nm.

BxpB is a major constituent of the basal layer in wildtype spores. Nevertheless, cryo-EM and cryo-sectioning show that ΔbxpB spores retain an intact basal layer (Fig. 2E, F), which previous studies have shown remains stably attached to the underlying spore (Steichen et al., 2005). The basal layer in ΔbxpB spores displays the same bilayered organization as wildtype spores, both by cryo-EM and cryo-sectioning (Fig. 2G, H). However, the prominent cross-striations and protrusions are absent, and the ΔbxpB spores lack the paracrystalline basal layer observed in both wildtype and ΔbclA spores. The ΔbxpB spores also lack the dense hair-like nap, consistent with the role of BxpB in attaching the BclA filaments. A few filaments are still present, presumably representing the 2% of BclA filaments that are attached to the BxpB paralog ExsFB (Sylvestre et al., 2005). Filaments are absent from most ΔbxpB cryo-sections, since longitudinal sections that cut through the ends of the spore where the filaments are located are relatively rare. Although the basal layer somewhat resembles a lipid bilayer and may contain lipid (Beaman et al., 1971), it does not consist primarily of lipid and is resistant to detergents (data not shown).

In this analysis, we also examined ΔexsB spores that lack the basal layer protein ExsB, which causes the exosporium to be readily sloughed from the spore (McPherson et al., 2010). Apart from this phenotype, micrographs of cryo-sections show that ΔexsB spores have an essentially normal exosporium with nap and with cross-striations and a hexagonal pattern in the basal layer (Fig. 2I).

3.3. Crystallographic analysis of purified exosporium fragments

To study the crystalline organization of the exosporium in greater detail, we imaged isolated wildtype, ΔbclA and ΔbxpB exosporium fragments by negative stain EM, followed by 2D crystallographic processing in 2dx (Gipson et al., 2007). The wildtype exosporium exhibited the same hexagonal lattice seen in the sections described above (Fig. 1E, G), consisting of hexagonal rings with holes in the middle and a lattice spacing of 8 nm (Fig. 3A, D). The crystalline pattern was less obvious in images of the ΔbclA exosporium, but 2D processing revealed a well ordered, hexagonal lattice consisting of hexagonal rings, similar to those in the wildtype (Fig. 3B, E). A 2D difference map between the wildtype and ΔbclA exosporium did not shown any significant differences between the two (Fig. 3G).

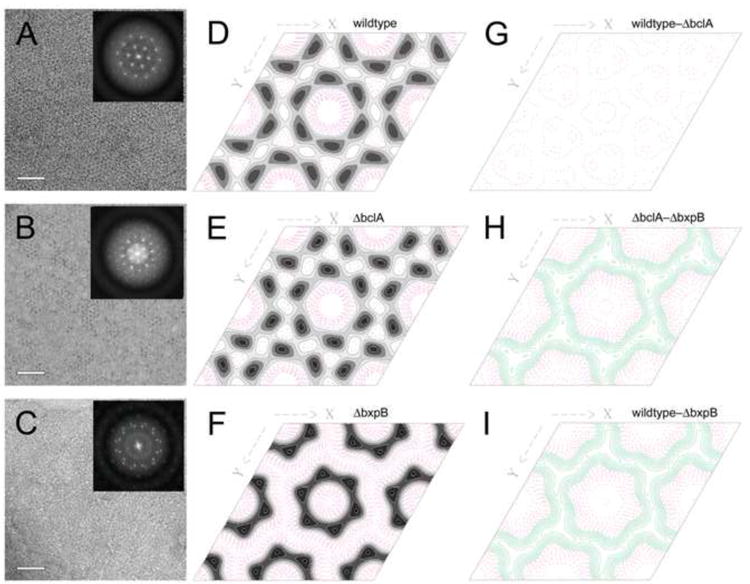

Figure 3.

2D crystallographic analysis of isolated exosporium fragments. (A-C) Micrographs of the negatively stained wildtype (A), ΔbclA (B) and ΔbxpB (C) exosporium and the power spectra of their Fourier transforms (insets). Scale bars are 50 nm. (D-F) Contour plots of the p6 symmetry projection maps of the wildtype, ΔbclA and ΔbxpB exosporium reconstructions are shown in in D, E and F, respectively. Positive density is shown in grayscale, negative density as red, dashed contours. (G-I) Contour plots of the difference maps between the wildtype and ΔbclA exosporium (G), between ΔbclA and ΔbxpB (H) and between the wildtype and ΔbxpB exosporium (I). In the difference maps, green contours are positive, red are negative. All maps were plotted on the same density scale.

The ΔbxpB exosporium was clearly less well ordered. In most cases, Fourier transforms revealed what appeared to be a rotationally averaged lattice with a primary lattice spacing of 8 nm (data not shown). In some cases, however, it was possible to find patches that appeared to consist of only two main superimposed lattices, thereby allowing 2D crystallographic analysis (Fig. 3C). When one of these lattices was indexed and processed, it also revealed hexagonal subunits with the same 8 nm lattice spacing as in the wildtype and ΔbclA exosporium, although the subunits themselves appeared to be somewhat smaller, with a smaller central hole (Fig. 3F). This suggests that the ΔbxpB exosporium contains the same hexagonal subunits as the wildtype, but that they are not organized with crystalline order. Difference maps between the ΔbxpB mutant and either the ΔbclA (Fig. 3H) or wildtype (Fig. 3I) exosporium indicate that while there is difference density surrounding the entire hexagonal subunit, it is mostly clustered at the threefold axes between the hexagonal subunits, suggesting that this is the location of BxpB.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have shown the organization of B. anthracis spores in the absence of fixation, staining and dehydration artifacts by cryo-EM, as well as through ultrathin cryo-sectioning using the Tokuyasu method and by analysis of negatively stained exosporium fragments. Based on our data, we can propose a model for the organization of BclA and BxpB in the B. anthracis exosporium (Fig. 4).

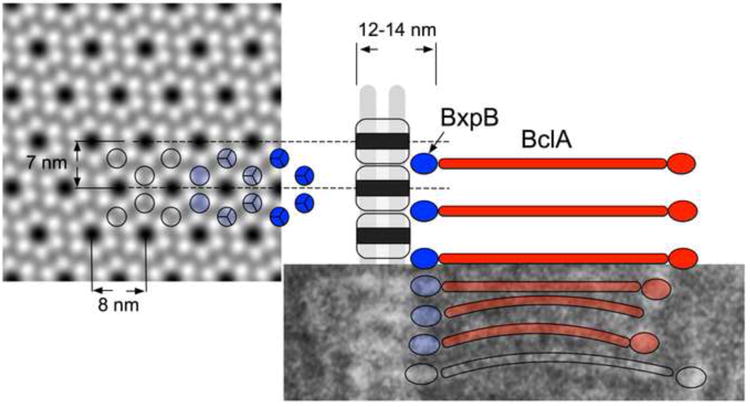

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the organization of BxpB (blue) and BclA (red) trimers in the exosporium. The two layers of density discernible in the 12-14 nm thick basal layer are shown in gray with the side views of the hexagonal subunits superimposed. The black rectangle indicates the hole in the middle of the hexagonal subunits. A magnified image of a wildtype cryo-section is shown below the schematic with relevant features superimposed. The p6 averaged surface view of the exosporium from the 2D reconstruction is shown on the left with the proposed location of the BxpB trimers shown (blue and open circles) on part of the array. Relevant dimensions are indicated. See text for details.

It is well established that BclA makes up the bulk of the filaments in the nap. In our images, these filaments appear to be continuous with protrusions in the basal layer that are absent in ΔbxpB mutants, suggesting that these features are made up of BxpB (Fig. 4). Structure prediction with I-TASSER (Zhang, 2008) indicates that BxpB is structurally homologous to the C-terminal knob domain of BclA (PDB ID: 3TWI), suggesting that BxpB, like BclA, forms trimers (Rety et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2008), and that there is a one-to-one correspondence between trimers of BclA and BxpB. A trimer of BxpB (17.3 kDa ×3 = 51.9 kDa) would correspond to a volume of 64 nm3, or a sphere of approximately 5 nm diameter—similar in size to the protrusions in the basal layer and about the same as the size of the BclA trimer comprising the filament knob (Rety et al., 2005).

BxpB is clearly not a primary structural component of the basal layer because ΔbxpB spores possess an intact and stable basal layer with the same bilayered appearance of wildtype and ΔbclA basal layers. Furthermore, the ΔbxpB exosporium contains hexagonal subunits similar to those found in the basal layer of wildtype and ΔbclA spores. Large, ordered crystalline arrays were absent, however, suggesting that such order is dependent on the presence of BxpB. Indeed, many exosporium proteins exhibit aberrant localization in ΔbxpB spores (Severson et al., 2009; McPherson et al., 2010; Thompson et al., 2011). Taken together, our data indicate that while other proteins form the main components of the hexagonal layer, their localization and crystalline order are dependent on BxpB, suggesting that BxpB acts as the “glue” that keeps the hexagonal subunits together and positions major structural proteins (Fig. 4). Supporting this model, difference maps (Fig. 3H,I) show that BxpB is located between the hexagonal subunits with the greatest density at positions of threefold symmetry. Taken together, our data indicate that the protrusions we attribute to BxpB are located at these threefold positions (Fig. 4). The presence of some ordered patches in the ΔbxpB mutant might be due to the presence of the BxpB paralog ExsFB, which could substitute for BxpB in these regions. The presence of filaments in these regions, which apparently can be attached to ExsFB, is consistent with this explanation. A similar observation was made by Sylvestre et al., who observed hexagonal layers in disrupted ΔbxpB (ΔexsFA) spores (Sylvestre et al., 2005).

Based on similarity in dimensions and symmetry, the hexagonal arrays that we observed in the wildtype basal layer appear to be the same as the “type II” crystals isolated from spores of B. anthracis, B. thuringiensis and B. cereus that were previously reported (Ball et al., 2008; Kailas et al., 2011). Our model is in concordance with that of Kailas et al. (Kailas et al., 2011), who proposed that BxpB forms “pillars” at the threefold axes of the hexagonal basal layer array. The BxpB-containing protrusions we observed are apparently the same as the structures termed “rectangular elements” by Couture-Tosi et al. (Couture-Tosi et al., 2010).

The question still remains as to the identity of the proteins that form the hexagonal subunits of the basal layer. High-resolution projection maps of the type II crystals suggested the presence of numerous αhelices (Kailas et al., 2011). The only identified exosporium protein with appreciable αhelical structure is the 109-residues ExsK (42% αhelix), while other proteins have 15% or less αhelix, based on PSIPRED (Buchan et al., 2010). Obviously, additional experiments will be required to identify the relevant structural proteins.

Our results also shed light on a controversial model that proposes BxpB attachment to the basal layer is dependent on first forming a complex with BclA (Thompson et al., 2011). Our images reveal that the structure of the basal layer is essentially identical in wildtype and ΔbclA spores, including the basal layer projections that we propose are comprised of BxpB trimers. We also demonstrate that the crystalline nature of the basal layer is lost in ΔbxpB spores, but not in ΔbclA spores, indicating that BxpB is functioning normally in the basal layer in the absence of BclA. Taken together, our observations are inconsistent with a co-dependency model for BclA and BxpB incorporation.

In conclusion, while many questions still remain regarding the organization and protein composition of the exosporium, we have shown the benefit of using cryo-EM methods to image B. anthracis spore mutants. This study represents one step towards a structural understanding of the B. anthracis exosporium and its role in defining spore virulence.

Acknowledgments

The EM work was carried out in the Cryo-EM core facility, Center for Structural Biology, at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. We are grateful to Bob Seiler (Leica Microsystems) for assistance with the cryo-sectioning. C.L.T. was funded by National Institutes of Health grant AI081775.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ascenzi P, Visca P, Ippolito G, Spallarosa A, Bolognesi M, Montecucco C. Anthrax toxin: a tripartite lethal combination. FEBS Let. 2002;531:384–388. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03609-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball DA, Taylor R, Todd SJ, Redmond C, Couture-Tosi E, Sylvestre P, Moir A, Bullough PA. Structure of the exosporium and sublayers of spores of the Bacillus cereus family revealed by electron crystallography. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:947–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Kang TJ, Chen WH, Fenton MJ, Baillie L, Hibbs S, Cross AS. Role of Bacillus anthracis spore structures in macrophage cytokine responses. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2351–2358. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01982-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaman TC, Pankratz HS, Gerhardt P. Paracrystalline sheets reaggregated from solubilized exosporium of Bacillus cereus. J Bacteriol. 1971;107:320–324. doi: 10.1128/jb.107.1.320-324.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaman TC, Pankratz HS, Gerhardt P. Ultrastructure of the exosporium and underlying inclusions in spores of Bacillus megaterium. J Bacteriol. 1972;109:1198–1209. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.3.1198-1209.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydston JA, Chen P, Steichen CT, Turnbough CL., Jr Orientation within the exosporium and structural stability of the collagen-like glycoprotein BclA of Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5310–5317. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5310-5317.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozue J, Cote C, Moody KL, Welkos SL. Fully virulent Bacillus anthracis does not require the immunodominant protein BclA for pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2007;75:508–511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01202-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan D, Ward S, Lobley A, Nugent T, Bryson K, Jones D. Protein annotation and modelling servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W563–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano RJ, Borucki MK. Revival and identification of bacterial spores in 25- to 40-million-year-old Dominican amber. Science. 1995;268:1060–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.7538699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCP4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleret A, Quesnel-Hellmann A, Vallon-Eberhard A, Verrier B, Jung S, Vidal D, Mathieu J, Tournier JN. Lung dendritic cells rapidly mediate anthrax spore entry through the pulmonary route. J Immunol. 2007;178:7994–8001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture-Tosi E, Ranck J, Haustant G, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Sachse M. CEMOVIS on a pathogen: analysis of Bacillus anthracis spores. Biol Cell. 2010;102:609–619. doi: 10.1042/BC20100080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Sirard J, Mock M, Koehler T. The atxA gene product activates transcription of the anthrax toxin genes and is essential for virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:1171–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubenspeck JM, Zeng H, Chen P, Dong S, Steichen CT, Krishna NR, Pritchard DG, Turnbough CLJ. Novel oligosaccharide side chains of the collagen-like region of BclA, the major glycoprotein of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30945–30953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon TC, Fadl AA, Koehler TM, Swanson JA, Hanna PC. Early Bacillus anthracis-macrophage interactions: intracellular survival and escape. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:453–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokland T, Ng ML. Electron microscopy of biological samples. In: Dokland T, Hutmacher DW, Ng ML, Schantz JT, editors. Techniques in microscopy for biomedical applications. World Scientific Press; Singapore: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dubochet J, Adrian M, Chang JJ, Homo JC, Lepault J, Mcdowall AW, Schultz P. Cryo-electron microscopy of vitrified specimens. Quart Rev Biophys. 1988;21:129–228. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubochet J, Mcdowall A, Menge B, Schmid EN, Lickfeld KG. Electron microscopy of frozen-hydrated bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:381–190. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.1.381-390.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt P, Ribi E. Ultrastructure of the exosporium enveloping spores of Bacillus cereus. J Bacteriol. 1964;88:1774–1789. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.6.1774-1789.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorno R, Bozue J, Cote C, Wenzel T, Moody KS, Mallozzi M, Ryan M, Wang R, Zielke R, Maddock JR, Friedlander A, Welkos S, Driks A. Morphogenesis of the Bacillus anthracis spore. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:691–705. doi: 10.1128/JB.00921-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson B, Zeng X, Zhang Z, Stahlberg H. 2dx--user-friendly image processing for 2D crystals. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BD, Battisi L, Koehler TM, Thorne CB, Ivins BE. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 1985;49:291–297. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.291-297.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi-Rontani C, Levy M, Ohayon H, Mock M. Fate of germinated Bacillus anthracis spores in primary murine macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:931–938. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi-Rontani C, Mock M. Macrophage interactions. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;271 doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05767-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques AO, Moran CP., Jr Structure and assembly of the bacterial endospore coat. Methods. 2000;20:95–110. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques AO, Moran CP., Jr Structure, assembly and function of the spore surface layers. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:555–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelsby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Friedlander AM, Hauer J, Mcdade J, Osterholm MT, O'Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Tonat K. Anthrax as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 1999;281:1735–1745. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kailas L, Terry C, Abbott N, Taylor R, Mullin N, Tzokov S, Todd S, Wallace B, Hobbs J, Moir A, Bullough P. Surface architecture of endospores of the Bacillus cereus/anthracis/thuringiensis family at the subnanometer scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16014–16019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109419108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TJ, Fenton MJ, Weiner MA, Hibbs S, Basu S, Baillie L, Cross AS. Murine macrophages kill the vegetative form of Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7495–7501. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7495-7501.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CQ, Nuttall SD, Tran H, Wilkins M, Streltsov VA, Alderton MR. Construction, crystal structure and application of a recombinant protein that lacks the collagen-like region of BclA from Bacillus anthracis spores. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;99:774–782. doi: 10.1002/bit.21637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckenney P, Driks A, Eichenberger P. The Bacillus subtilis endospore: assembly and functions of the multilayered coat. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcpherson S, Li M, Kearney J, Turnbough CJ. ExsB, an unusually highly phosphorylated protein required for the stable attachment of the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:1527–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moayeri N, Leppla SH. The roles of anthrax toxin in pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock M, Fouet A. Anthrax. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:647–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WL, Setlow P. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth. In: Harwood CR, Cutting SM, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons; West Sussex: 1990. pp. 391–450. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva CR, Swiecki MK, Griguer CE, Lisanby MW, Bullard DC, Turnbough CL, Jr, Kearney JF. The integrin Mac-1 (CR3) mediates internalization and directs Bacillus anthracis spores into professional phagocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1261–1266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond C, Baillie LW, Hibbs S, Moir AJG, Moir A. Identification of proteins in the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. Microbiology. 2004;150:355–363. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rety S, Salamitou S, Garcia-Verdugo I, Hulmes DJ, Le Hegarat F, Chaby R, Lewit-Bentley A. The crystal structure of the Bacillus anthracis spore surface protein, BclA, shows remarkable similarilty to mammalian proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43073–43078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez J, White D, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson K, Mallozzi M, Bozue J, Welkos S, Cote C, Knight K, Driks A. Roles of the Bacillus anthracis spore protein ExsK in exosporium maturation and germination. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7587–7596. doi: 10.1128/JB.01110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steichen CT, Chen P, Kearney JF, Turnbough CL., Jr Identification of the immunodominant protein and other proteins of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1903–1910. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1903-1910.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steichen CT, Kearney JF, Turnbough CL., Jr Characterization of the exosporium basal layer protein BxpB of Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2868–5876. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.5868-5876.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steichen CT, Kearney JF, Turnbough CL., Jr Non-uniform assembly of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium and a bottle cap model for spore germination and outgrowth. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiecki MK, Lisanby MW, Shu F, Turnbough CL, Jr, Kearney JF. Monoclonal antibodies for Bacillus anthracis spore detection and functional analyses of spore germination and outgrowth. J Immunol. 2006;176:6076–6084. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre P, Couture-Tosi E, Mock M. A collagen-like surface glycoprotein is a structural component of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:169–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.03000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre P, Couture-Tosi E, Mock M. Polymorphism in the collagen-like region of the Bacillus anthracis BclA protein leads to variation in the exosporium filament length. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1555–1563. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1555-1563.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre P, Couture-Tosi E, Mock M. Contribution of ExsFA and ExsFB proteins to the localization of BclA on the spore surface and to the stability of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5122–5128. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5122-5128.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Turnbough CJ. Sequence motifs and proteolytic cleavage of the collagen-like glycoprotein BclA required for its attachment to the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1259–1268. doi: 10.1128/JB.01003-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BM, Stewart GC. Targeting of the BclA and BclB proteins to the Bacillus anthracis spore surface. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:421–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, Hsieh H, Spreng K, Stewart G. The co-dependence of BxpB/ExsFA and BclA for proper incorporation into the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:799–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuyasu KT. A technique for ultracryotomy of cell suspensions and tissues. J Cell Biol. 1973;57:551–565. doi: 10.1083/jcb.57.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbough CL., Jr Discovery of phage display peptide ligands for species-specific detection of Bacillus spores. J Microbiol Meth. 2003;53:263–271. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(03)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver J, Kang TJ, Raines KW, Cao GL, Hibbs S, Tsai P, Baillie L, Rosen GM, Cross AS. Protective role of Bacillus anthracis exosporium in macrophage-mediated killing by nitric oxide. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3894–3901. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00283-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G, Linley E, Nicholas R, Baillie L. The role of the exosporium in the environmental distribution of anthrax. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;114:396–403. doi: 10.1111/jam.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]