Abstract

We report a method based on thiol-ene chemistry that enables the synthesis and purification of ubiquitin oligomers with ≥ 4 units. This is the first time in which a free-radical polymerization is used to construct oligomers that functionally mimic natural biopolymers. This approach can be applied towards the synthesis of 6-linked ubiquitin oligomers currently inaccessible by enzymatic methods. Using these chains, one can study their roles in the ubiquitin proteasome system and the DNA damage response pathway.

Keywords: ubiquitin, site-specific modification, thiol-ene polymerization

In eukaryotes, covalent attachment of ubiquitin (Ub) to target proteins is involved in regulating nearly all biological processes.[1] The most well known function of Ub is in targeting proteins for degradation through the Ub proteasome system (UPS).[2] For UPS processing, the prevailing view has been that a target protein must be modified with a polyUb chain consisting of a minimum of four Ub subunits linked between the C-terminus of one unit to lysine (Lys)-48 of the preceding unit (the Nε-Gly-l-Lys linkage is commonly referred to as an isopeptide bond).[3,4] Recent studies, however, suggest the polyUb signal can be much more diverse. That is, chains bearing linkages originating from any of the seven Ub lysines (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, and Lys63) or the N-terminal methionine are thought to promote protein turnover in vivo.[5–9]

We have been interested in understanding the function of unconventional Lys6-linked polyUb chains, as these particular signals are a product of the E3 Ub ligase activity exhibited by the breast cancer associated protein (BRCA1).[10,11] BRCA1 is a major player in the DNA damage response (DDR) pathway and hereditary mutations predispose women to breast and ovarian cancers.[12,13] The role of Lys6-linked chains in DDR remains unclear. Some studies implicate these chains in proteasomal degradation,[7,8,14,15] while others argue for a non-proteolytic role.[16,17] Even the importance of BRCA1 E3 Ub ligase activity in DDR and tumor suppression has been called into question.[18] Many of these issues could be resolved by deciphering how Lys6-linked chains are recognized and processed by the proteasome and DDR machinery. Generating the requisite polyUb oligomers for these studies, however, remains challenging. Enzymatic methods are not amenable to the production of 6-linked chains[19,20] and the execution of current chemical approaches is not straightforward.[21–25] Herein we report on a method using free-radical thiol-ene coupling (TEC)[26] to rapidly produce well-defined 6-linked Ub oligomers as well as other topological isomers. We also show that these oligomers can be used to investigate substrate preferences of proteasomal components.

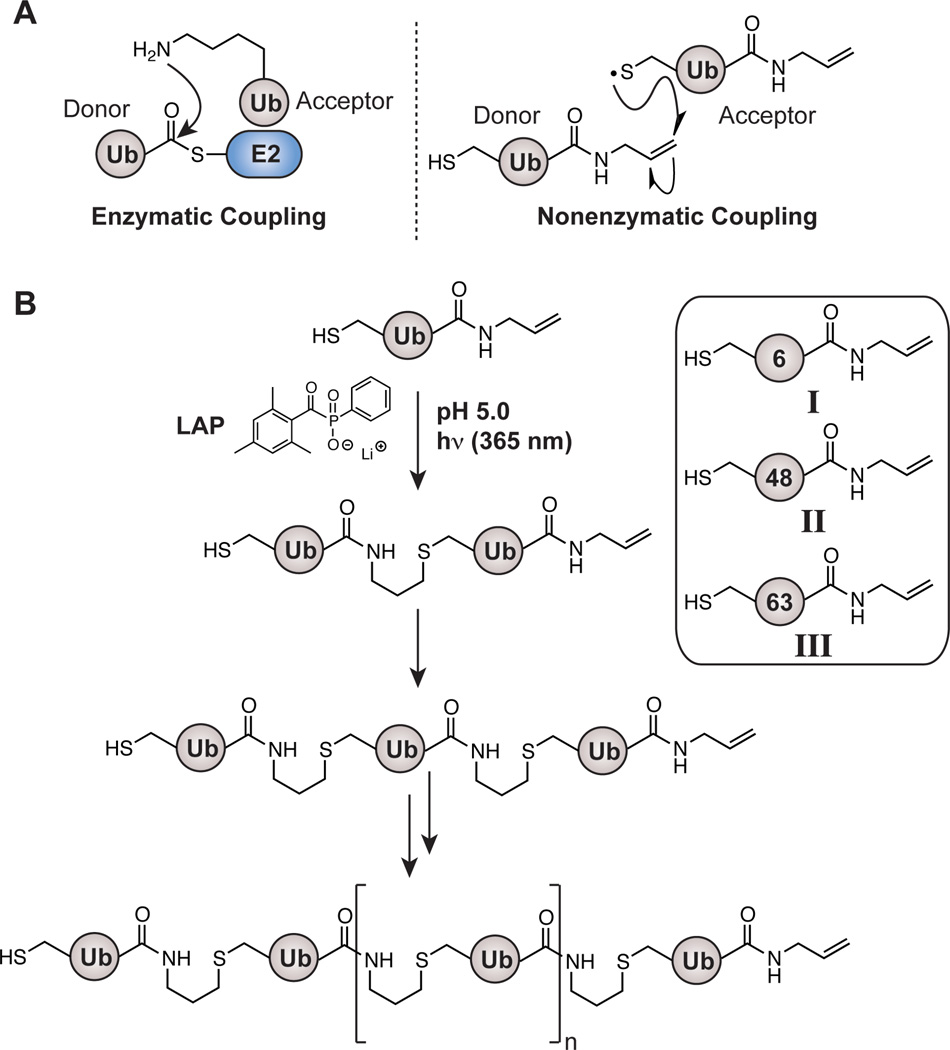

Our plan was to emulate the enzymatic logic of polyUb chain formation. Three enzymes – E1 Ub-activating, E2 Ub-conjugating, and E3 Ub-ligating – catalyze Ub polymerization.[27,28] In some cases, a few E2 enzymes are capable of catalyzing the formation of linkage-specific polyUb chains in vitro in the absence of an E3.[20,29,30] E2 enzymes achieve linkage specificity by orienting a particular lysine of an acceptor Ub for nucleophilic attack on the donor ubiquityl thioester (Figure 1A).[31–33] Single-linkage (homotypic) oligomers of different lengths are then generated after successive rounds of conjugation through a step-growth polymerization process. With this mechanism as a model, we envisioned expanding the repertoire of enzymatically derived homotypic chains beyond Lys11-, Lys48-, and Lys63-linkages by using a dually functionalized Ub monomer (Figure 1A). In this Ub variant, the C-terminal allyl amine appendage acts as the activated E2-S-Ub intermediate and the thiol moiety of cysteine serves as the lysine surrogate providing linkage-specificity. Free-radical thiol-ene polymerization[26,34] is then used to forge an isopeptide-like bond (Nε-l-Gly-homothiaLys) between multiple Ub subunits (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Comparison between enzymatic and nonenzymatic coupling. Ub charged E2 thioester (E2-S-Ub) interacts with an acceptor Ub to catalyze isopeptide (Nε-Gly-L-Lys) bond formation. For the nonenzymatic approach a free-radical TEC strategy is shown with a dually functionalized Ub monomer harboring a C-terminal allyl amine adduct and a lysine-to-cysteine mutation. (B) Scheme depicting nonenzymatic polymerization initiated using lithium acyl phosphinate (LAP) and 365 nm light. Discrete oligomers are linked through an Nε-Gly-l-homothiaLys isopeptide-like bond. The three dually functionalized Ub monomers (I–III) used in this study are also shown, wherein the numbers denote the lysine residue mutated to cysteine.

Polymerization of monomers I–III was examined with the goal of constructing (i) a set of oligomers harboring linkages currently unattainable by enzymatic methods (6-linked chains), and (ii) a control series with enzymatically available 48- and 63-linkages.[19,20,35] Exposing I–III to thiol-ene conditions revealed rapid formation of a series of discrete oligomers (Figure S2). The extent of oligomer formation, however, varied depending on the linkage forged. For example, polymerization of II afforded higher molecular weight oligomers in comparison to the reaction with I (Figure S12). This difference is likely due to the relative steric hindrance of the two positions; position-6, being part of a β-sheet, is less exposed relative to the loop region in which position-48 is located. Consistent with a fast chain termination process,[36–38] we also observed that conversion stopped almost immediately after reactions were initiated.

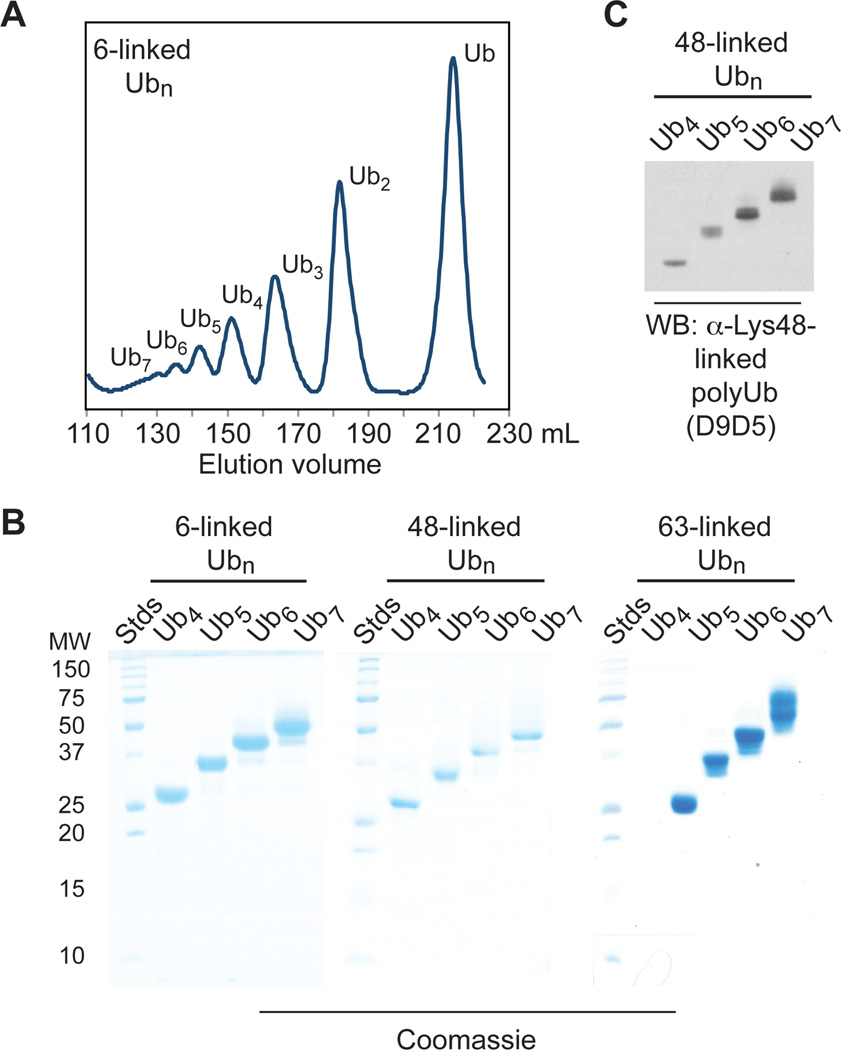

After scaling up the polymerization reactions, size-exclusion chromatography was used to isolate discrete oligomers. Chromatograms of the crude polymerizations showed separation of oligomers ranging from dimers to heptamers (Figure 2A). This enabled isolation of the entire series from tetramers to heptamers for 6-, 48-, and 63-linked Ub oligomers in milligram quantities (Figure 2B). Each of the 48- and 63-linked oligomers exhibited binding to commercially available monoclonal antibodies raised against polyUb chains linked through native isopeptide bonds (Figure 2C and S3). These results demonstrate the ease with which long polyUb chains can be produced using thiol-ene polymerization.

Figure 2.

Isolation of discrete 6-, 48-, and 63-linked Ub oligomers. (A) Size-exclusion chromatogram of the crude polymerization of monomer I. (B) Coomassie-stained SDS PAGE analysis of purified 6-, 48-, and 63-linked Ub oligomers. (C) Western blot (WB) analysis of 48-linked oligomers using the D9D5 monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology).

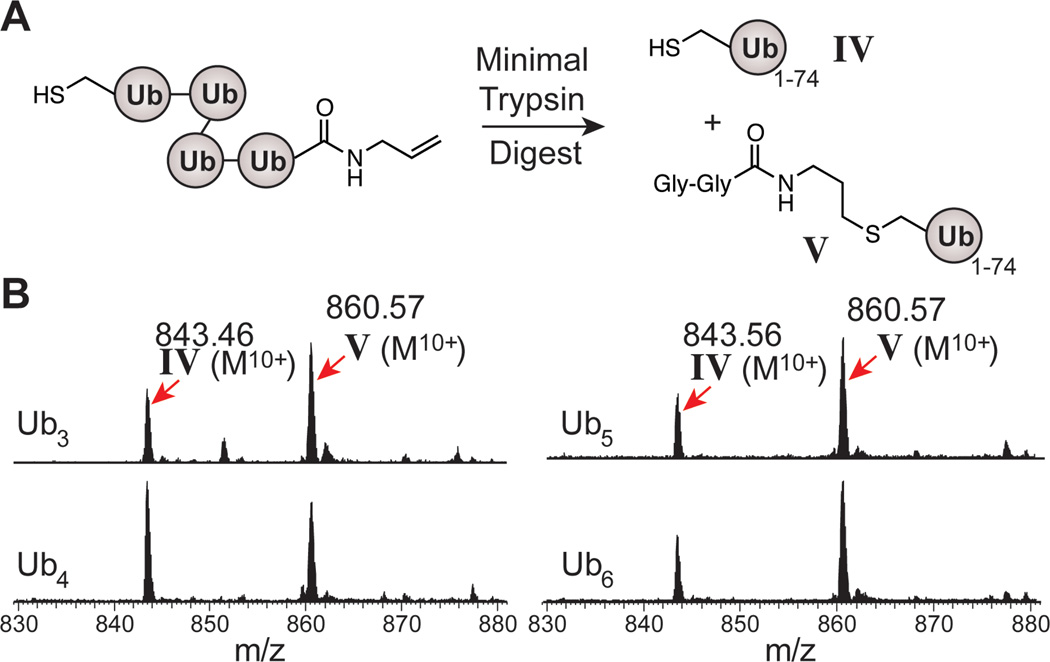

Next, it was important to confirm that each Ub subunit is linked through an Nε-Gly-L-homothiaLys isopeptide-like bond. To this end, Fourier-transform ion cyclotron (FT-ICR) MS analysis was employed. Exploiting the stability of Ub in the presence of trypsin, oligomers were minimally digested to generate two species: Ub1–74 (IV) and Ub1–74 with a 171.2 amu addition due to the Gly-Gly-allyl amine appendage (V) (Figure 3A).[26,39,40] MS analysis of these digests demonstrated the presence of both IV and V (Figure 3B). Note that if undesired C-S or C-C radical recombination products formed during polymerization, our minimal digest approach would identify these products. However, no other Ub variants carrying cysteine modifications besides V were observed. All position-specific modifications were verified by electron capture dissociation (ECD) and/or collision-activated dissociation (CAD) MS/MS analysis (see Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Characterization of Ub oligomers. (A) Minimal trypsin digest of oligomers results in the formation of two distinct Ub monomers IV and V. (B) Representative FT-ICR MS spectra of minimal trypsin digests of various 6-linked oligomers. All peaks are shown in the M10+ ionization state.

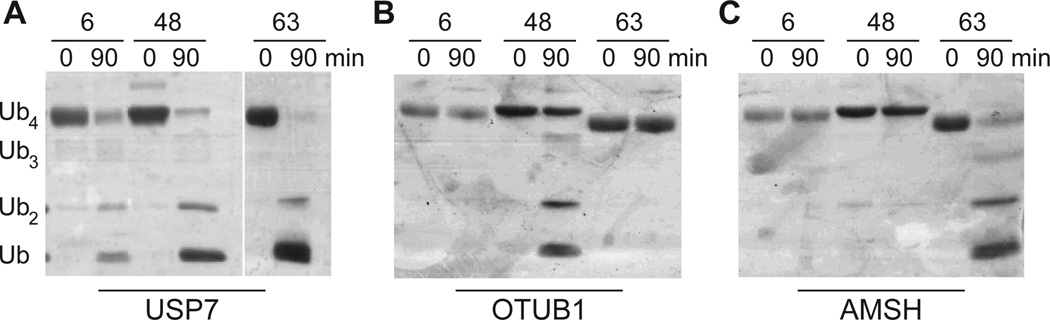

To investigate the function of 6-linked chains, we wanted to determine whether the oligomers could serve as substrates for deubiquitinases (DUBs). For these experiments we used three distinct enzymes: a promiscuous DUB USP7[41], a Lys48-linkage selective DUB OTUB1[42], and a Lys63-linkage linkage selective DUB AMSH.[43] USP7 disassembled each of the linkages within 90 minutes (Figure 4A). By contrast, the linkage selective DUBs OTUB1 and AMSH only degraded preferred substrates (Figure 4B and 4C). With these observations we conclude that tetramers forged through thiol-ene polymerizations are good models for native oligomers, and can be employed in assays with the proteasome.

Figure 4.

Deubiquitinase assays with different Ub oligomers. (A) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of tetramer (10 µM) hydrolysis with USP7 (1 µM). (B) OTUB1-catalyzed (1 µM) hydrolysis of Ub tetramers (10 µM). (C) AMSH-catalyzed (1 µM) hydrolysis of Ub tetramers (10 µM).

The 26S proteasome is comprised of a 20S proteolytic core capped on both ends by a 19S regulatory particle (referred to as PA700).[44] In the fully assembled 26S proteasome holocomplex there are three DUBs affiliated with PA700: the cysteine proteases USP14 and UCH37, and the zinc-dependent metalloprotease POH1/RPN11.[45] Mounting evidence suggests POH1 promotes substrate degradation,[46,47] while USP14 and UCH37 antagonize protein turnover.[48,49] The cysteine proteases are proposed to suppress degradation by different mechanisms, as USP14 regulates proteasome activity through a non-catalytic function and UCH37 controls the lifetime of proteasome-substrate interactions by trimming polyUb chains from the distal end.[48,50] Based on this logic, a polyUb chain that is readily hydrolyzed by UCH37 will not support proteasomal degradation to the same extent as a chain processed less efficiently. As Liu and coworkers have shown, Lys63-linked chains are trimmed more rapidly than Lys48-linkages by 26S proteasomes and PA700.[15] These data have been used to explain, in part, why Lys48-linked chains act as proteasome-targeting signals whereas Lys63-linked chains play non-degradative roles.

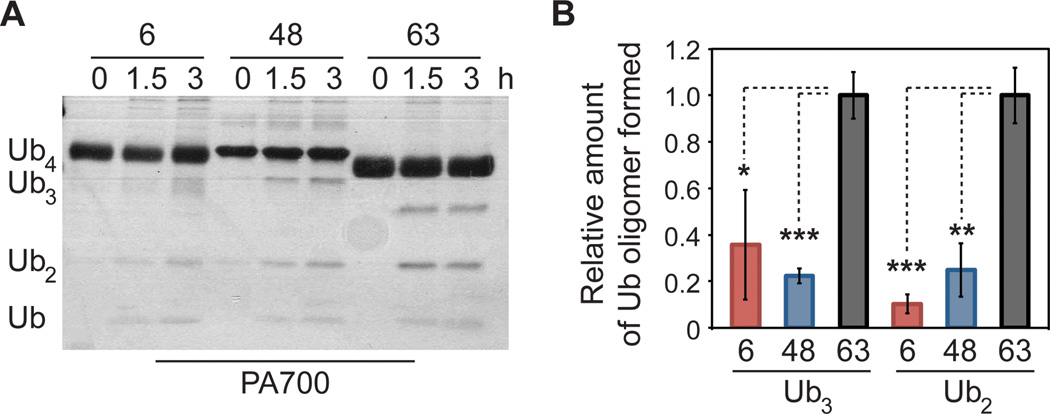

To compare the stability of 6-linked oligomers with its topoisomers, each chain was interrogated with human PA700. In our initial experiments with human 26S proteasomes we detected negligible disassembly of oligomers composed of either native or Nε-Gly-L-homothiaLys linkages. Therefore, we turned to purified human PA700. Deubiquitination assays with this enzyme complex consistently showed formation of smaller oligomeric species arising from 6-, 48-, and 63-linked tetramers (Figure 5A). Analyzing the amounts of each hydrolytic product revealed important trends in reactivity. First, 63-linked tetramers were cleaved to a greater extent than either 6- or 48-linked oligomers. In particular, we observed a statistically significant three- to fivefold increase in the amount of 63-linked trimers and dimers formed after 1.5 h relative to the other two topoisomers (Figure 5B). This is consistent with a six-fold difference in trimming rates previously reported with 26S proteasomes and PA700 purified from bovine red blood cells.[15] Second, the levels of cleavage products for 6- and 48-linked tetramers were nearly identical, implying similar half-lives for Lys6- and Lys48-linked polyUb chains. On this basis, we argue Lys6-linked chains can also promote proteasomal degradation. Additional experiments with target proteins carrying well-defined polyUb chains will allow us validate this hypothesis.

Figure 5.

PA700-catalyzed cleavage of Ub tetramers. (A) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of tetramer (10 µM) hydrolysis with PA700 (100 nM). Tetramer concentrations were tenfold higher than the previously reported Michaelis constants for the 26 proteasome/PA700-mediated cleavage of Lys48- and Lys63-linked tetramers (Km ~ 1 µM for both chain types) to ensure saturation. (B) Relative amounts of Ub trimers and dimers (Ub3 and Ub2) formed after incubating tetramers with PA700 for 1.5 h. Bands corresponding to individual oligomers were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). The average (data was normalized to 63-linked tetramers) of three separate experiments is shown. *, P-value = 0.01; **, P-value = 0.0015; ***, P-value ≤ 0.0003.

In summary, this work highlights how free-radical thiol-ene polymerizations can be applied to the nonenzymatic synthesis of polyUb chains with well-defined linkages. Using this approach we have shown for the first time that homotypic polyUb chains with up to seven subunits can be obtained in a single step. Although this methodology generates a non-native linkage between Ub subunits, we demonstrate that it does not impact linkage specific enzymes. In fact, we show that these oligomers can be used to inform on the biochemical function of different Ub oligomers in the context of the proteasome. With rapid access to long chains we will be able to gain more insight into the role of 6-linked chains in the DNA damage response pathway as well as the UPS.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We thank Prof. A. Hoskins for use of the fluorescent imager and Prof. M. Mahanthappa for critical reading of the manuscript. The deubiquitinases IsoT, OTUB1, USP7, and AMSH were a kind gift from LifeSensors Inc. Financial support was provided by UW-Madison, the Greater Milwaukee Shaw Scientist Program, Susan G. Komen for Cure, NSF (graduate fellowship awarded to V.H.T.), the Wisconsin Partnership Fund for the establishment of the University of Wisconsin Human Proteomics Program (Y.G.), and NIH (R01HL096971 awarded to Y.G.). The NSF (9520868) is also acknowledged for support of the UW-Madison Chemistry Instrumentation Center.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org

Contributor Information

Vivian H. Trang, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1101 University Ave. Madison, Wi 53706

Ellen M. Valkevich, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1101 University Ave. Madison, Wi 53706

Shoko Minami, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1101 University Ave. Madison, Wi 53706.

Yi-Chen Chen, Department of Cell and Regenerative Biology, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1300 University Ave. Madison, WI 53706.

Ying Ge, Department of Cell and Regenerative Biology, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1300 University Ave. Madison, WI 53706.

Eric R. Strieter, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1101 University Ave. Madison, Wi 53706.

References

- 1.Grabbe C, Husnjak K, Dikic I. Nat. Rev. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nrm3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrower JS, Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M, Pickart CM. EMBO J. 2000;19:94–102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chau V, Tobias JW, Bachmair A, Marriott D, Ecker DJ, Gonda DK, Varshavsky A. Science. 1989;243:1576–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirisako T, Kamei K, Murata S, Kato M, Fukumoto H, Kanie M, Sano S, Tokunaga F, Tanaka K, Iwai K. EMBO J. 2006;25:4877–4887. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkpatrick DS, Hathaway NA, Hanna J, Elsasser S, Rush J, Finley D, King RW, Gygi SP. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:700–710. doi: 10.1038/ncb1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu P, Duong DM, Seyfried NT, Cheng D, Xie Y, Robert J, Rush J, Hochstrasser M, Finley D, Peng J. Cell. 2009;137:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dammer EB, Na CH, Xu P, Seyfried NT, Duong DM, Cheng D, Gearing M, Rees H, Lah JJ, Levey AI, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:10457–10465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.149633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saeki Y, Kudo T, Sone T, Kikuchi Y, Yokosawa H, Toh-e A, Tanaka K. EMBO J. 2009;28:359–371. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu-Baer F. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34743–34746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300249200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishikawa H, Ooka S, Sato K, Arima K, Okamoto J, Klevit RE, Fukuda M, Ohta T. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3916–3924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huen MSY, Sy SM-H, Chen J. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:138–148. doi: 10.1038/nrm2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li ML, Greenberg RA. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedford L, Layfield R, Mayer RJ, Peng J, Xu P. Neurosci. Lett. 2011;491:44–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson AD, Zhang NY, Xu P, Han KJ, Noone S, Peng J, Liu CW. J. Biol. l Chem. 2009;284:35485–35494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato K, Hayami R, Wu W, Nishikawa T, Nishikawa H, Okuda Y, Ogata H, Fukuda M, Ohta T. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30919–30922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu X, Fu S, Lai M, Baer R, Chen J. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1721–1726. doi: 10.1101/gad.1431006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shakya R, Reid LJ, Reczek CR, Cole F, Egli D, Lin C-S, deRooij DG, Hirsch S, Ravi K, Hicks JB, et al. Science. 2011;334:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1209909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickart CM, Raasi S. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:21–36. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong KC, Helgason E, Yu C, Phu L, Arnott DP, Bosanac I, Compaan DM, Huang OW, Fedorova AV, Kirkpatrick DS, et al. Structure. 2011;19:1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strieter ER, Korasick DA. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:52–63. doi: 10.1021/cb2004059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spasser L, Brik A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:6840–6862. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar KSA, Bavikar SN, Spasser L, Moyal T, Ohayon S, Brik A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6137–6141. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bavikar SN, Spasser L, Haj-Yahya M, Karthikeyan SV, Moyal T, Ajish Kumar KS, Brik A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;51:758–763. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castañeda C, Liu J, Chaturvedi A, Nowicka U, Cropp TA, Fushman D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17855–17868. doi: 10.1021/ja207220g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valkevich EM, Guenette RG, Sanchez NA, Chen Y-C, Ge Y, Strieter ER. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6916–6919. doi: 10.1021/ja300500a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickart CM. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofmann RM, Pickart CM. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:27936–27943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Z, Pickart CM. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:21835–21842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigo-Brenni MC, Foster SA, Morgan DO. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:548–559. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wickliffe KE, Lorenz S, Wemmer DE, Kuriyan J, Rape M. Cell. 2011;144:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saha A, Lewis S, Kleiger G, Kuhlman B, Deshaies RJ. Mol Cell. 2011;42:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoyle CE, Bowman CN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:1540–1573. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piotrowski J, Beal R, Hoffman L, Wilkinson KD, Cohen RE, Pickart CM. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23712–23721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovestead TM, Berchtold KA, Bowman CN. Macromolecules. 2005;38:6374–6381. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy SK, Cramer NB, Bowman CN. Macromolecules. 2006;39:3673–3680. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowman CN, Kloxin CJ. AIChE J. 2008;54:2775–2795. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkinson KD, Cox MJ, Mayer AN, Frey T. Biochemistry. 1986;25:6644–6649. doi: 10.1021/bi00369a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu P, Peng J. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:3438–3444. doi: 10.1021/ac800016w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faesen AC, Luna-Vargas MPA, Geurink PP, Clerici M, Merkx R, van Dijk WJ, Hameed DS, El Oualid F, Ovaa H, Sixma TK. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:1550–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edelmann MJ, Iphöfer A, Akutsu M, Altun M, di Gleria K, Kramer HB, Fiebiger E, Dhe-Paganon S, Kessler BM. Biochem. J. 2009;418:379–390. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sato Y, Yoshikawa A, Yamagata A, Mimura H, Yamashita M, Ookata K, Nureki O, Iwai K, Komada M, Fukai S. Nature. 2008;455:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature07254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finley D. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee MJ, Lee B-H, Hanna J, King RW, Finley D. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.R110.003871. R110.003871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verma R, Aravind L, Oania R, McDonald H, Yates JR, Koonin EV, Deshaies RJ. Science. 2002;298:611–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1075898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao T, Cohen RE. Nature. 2002;419:399–403. doi: 10.1038/nature01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lam YA, Xu W, DeMartino GN, Cohen RE. Nature. 1997;385:737–740. doi: 10.1038/385737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koulich E, Li X, DeMartino GN. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:1072–1082. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanna J, Hathaway NA, Tone Y, Crosas B, Elsasser S, Kirkpatrick DS, Leggett DS, Gygi SP, King RW, Finley D. Cell. 2006;127:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.