Abstract

Two constituents of bile, bilirubin and tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), have antioxidant activity. However, bilirubin can also cause damage to some neurons and glial cells, particularly immature neurons. In this study, we tested the effects of bilirubin and TUDCA in two models in which oxidative stress contributes to photoreceptor cell death, prolonged light exposure and rd10+/+ mice. In albino BALB/c mice, intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 5 mg/kg of bilirubin or 500 mg/kg of TUDCA prior to exposure to 5,000 lux of white light for 8 hours significantly reduced loss of rod and cone function assessed by electroretinograms (ERGs). Both treatments also reduced light-induced accumulation of superoxide radicals in the outer retina, rod cell death assessed by outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness, and disruption of cone inner and outer segments. In rd10+/+ mice, IP injections of 5 or 50 mg/kg of bilirubin or 500 mg/kg of TUDCA every 3 days starting at postnatal day (P) 6, caused significant preservation of cone cell number and cone function at P50. Rods were not protected at P50, but both bilirubin and TUDCA provided modest preservation of ONL thickness and rod function at P30. These data suggest that correlation of serum bilirubin levels with rate of vision loss in patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) could provide a useful strategy to test the hypothesis that cones die from oxidative damage in patients with RP. If proof-of-concept is established, manipulation of bilirubin levels and administration of TUDCA could be tested in interventional trials.

Keywords: antioxidants, oxidative damage, retinal photoreceptors, reactive oxygen species, retinal dystrophies, retinitis pigmentosa

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a group of diseases in which a mutation leads to rod cell death. Hundreds of different mutations that lead to RP have been identified. The mechanism of rod cell death is likely to vary depending upon the mutation. Some mutations in genes that are differentially expressed in rod photoreceptors cause protein misfolding and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress leading to rod cell death (Hwa et al. 1999; Illing et al. 2002; Aherne et al. 2004; Tam and Moritz 2006). Other proposed mechanisms include continuous activation of phototransduction, abnormal cellular transport, or instability of inner or outer segments due to dysfunction of structural proteins (Liu et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2006; Krebs et al. 2010). Since the regeneration of rhodopsin depends upon the retinoid cycle through which all-trans-retinal is converted back to 11-cis-retinal which binds with opsin, dysfunctions in phototransduction can result in abnormalities in the retinoid cycle and vice versa. Disruption of the retinoid cycle causes elevated levels of highly reactive retinoids, such as all-trans retinal, which are toxic. In fact, excessive and/or prolonged light stimulation in normal animals leads to photoreceptor degeneration from accumulation of all-trans retinal (Maeda et al. 2009). The heterogeneity in the mechanism of rod cell death in RP suggests that any one particular treatment is likely to apply only to a small subgroup of patients that share the same mechanism.

However, it is not the death of rods that is debilitating in patients with RP, but rather the death of cones that inevitably follows rod cell death. Loss of rods decreases function in dim illumination but not normal illumination, whereas loss of cones leads to constriction of the visual fields and eventual blindness. Rods make up the majority of cells in the outer retina, roughly 98% in mice and 92% in humans, but the percentage varies considerably based upon the position within the retina (Curcio et al. 1993). Rods are metabolically active cells that consume the vast majority of oxygen delivered to the outer retina. After rods die, oxygen delivery is unchanged, but oxygen consumption is greatly reduced resulting in a large increase in oxygen in the outer retina (Yu et al. 2000). The increase in oxygen results in generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) from stimulation of NADPH oxidase and probably also from run off from the electron transport chain, resulting in progressive oxidative damage and death of cones (Shen et al. 2005; Komeima et al. 2006; Usui et al. 2009a). Oxidative damage contributes to cone cell death in several models of RP with different underlying pathogenic mutations (Komeima et al. 2007) and thus may be applicable in all patients with RP. Thus, development of new treatments that effectively protect photoreceptors from oxidative stress is a high priority. Such treatments may also provide benefit in patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), because antioxidant vitamins reduce the risk of progression from intermediate to advanced forms of the disease (Age-Related 2001).

An appealing therapeutic strategy is to utilize components of the endogenous antioxidant defense system since they are likely to be well-tolerated. Each tissue contains a group of enzymes that detoxify reactive oxygen species, but it is difficult to utilize enzymes as therapeutic agents. Some small molecules that seem to play other roles in the body may also be components of the antioxidant defense system. Bilirubin, the end product of heme metabolism and uric acid, the end product of purine metabolism, have antioxidant activity (Stocker et al. 1987a; Stocker et al. 1987b). The evidence that bilirubin has a physiological function as an antioxidant is particularly strong. Elevated plasma bilirubin levels provide protection in a number of disease processes in which oxidative stress has been implicated (Ishizaka et al. 2001; Vitek et al. 2002; Djousse et al. 2003; Novotny and Vitek 2003). Local production of bilirubin through heme oxygenase 1 (HO1) or HO2 and biliverdin reductase also provides protection against oxidative stress in some tissues (Llesuy and Tomaro 1994). In some neuronal populations, HO2 is particularly important, because mice deficient in HO2 show increased ischemia-induced damage in some brain regions (Dore et al. 1999b; Dore et al. 1999a; Dore et al. 2000).

Like bilirubin, other constituents of bile, the bile acids, can either be damaging or protective to cells. Most bile acids are hydrophobic, very insoluble, and in high concentrations cause damage to cell membranes. Obstruction of bile ducts or liver diseases can result in elevated levels of bile acids, cholestasis, which is damaging to the liver. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a minor (4%) constituent of bile, is hydrophilic unlike other bile salts and when given as an oral supplement, reduces liver damage in the setting of cholestasis; it has been approved by the Federal Drug Administration for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (Lazaridis et al. 2001). While the exact mechanism of its protective effect for liver cells is not known, it has been demonstrated that UDCA reduces apoptosis induced by hydrophobic bile salts, possibly by membrane stabilization and/or reducing mitochondrial damage (Heuman and Bajaj 1994; Botla et al. 1995; Rodrigues et al. 1998). Also, both UDCA and its taurine-conjugated analog, TUDCA, have cytoprotective effects in a number of animal models including models of retinal degeneration (Boatright et al. 2006; Phillips et al. 2008). In this study, we investigated the effects of bilirubin and TUDCA on photoreceptor survival and function in a model of excessive light exposure and a model of RP.

Materials and Methods

Treatment with bilirubin IX-α or TUDCA

Mice were treated in accordance with the recommendations of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. In these experiments, bilirubin IX-α was bound to human serum albumin (HSA) prior to administration, because HSA is the physiologic carrier for bilirubin and free bilirubin is not available to peripheral tissues. Bilirubin IX-α was dissolved in 50 mM NaOH in distilled water and incubated with HSA in a ratio of 1:140 to obtain bilirubin bound to HSA. Litters of homozygous rd10+/+ transgenic mice or BALB/c mice were given subcutaneous injections of bilirubin (5 mg/kg)/HSA (700 mg/kg) or TUDCA (500 mg/kg) dissolved in 0.15 M NaHCO3. The control group for bilirubin-treated mice was given injections of 700 mg/kg of HSA and the control group for TUDCA-treated mice was given 0.15 M NaHCO3.

Light-induced retinal degeneration model

One day and again 1 hour prior to light exposure (5000 lux for 8 hours), 4–6 week old female albino BALB/c mice were given an injection of bilirubin, HSA, TUDCA, or NaHCO3. Female mice were used for these experiments because they are less aggressive resulting in fewer injuries from fighting, but there is no scientific reason to exclude males. Solutions were prepared immediately prior to injections and pH was adjusted to 7.4. After 8 hours of light exposure, mice were dark adapted for 18 hours and then scotopic and photopic electroretinograms (ERGs) were performed (Day 1 ERGs). Mice were then housed under normal cyclic lighting conditions (light 12 hours/dark 12 hours). On day 7, scotopic and photopic ERGs were repeated and mice were euthanized to measure outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness or cone density. Some mice received an injection of hydroethidine prior to death to assess superoxide radicals in the retina.

Rd10 model of retinal degeneration

Rd10+/+ mice were purchased from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME) and were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. Starting at postnatal day (P) 6, both males and females were given subcutaneous injections of 5 mg/kg of bilirubin, 500 mg/kg of TUDCA, or their respective control injections every three days. At P30, scotopic and photopic ERGs were done and some mice were euthanized to measure ONL thickness. At P50, ERGs were done and mice were euthanized to measure ONL thickness or cone density.

Assessment of superoxide radicals with hydroethidine

The in situ production of superoxide radicals was evaluated using hydroethidine as previously described (Komeima et al. 2008). Superoxide radicals convert hydroethidine to ethidium, which binds DNA and emits red fluorescence at approximately 600 nm. Briefly, two intraperitoneal injections of 20 mg/kg of hydroethidine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were administered 30 minutes apart and mice were kept in the dark for 18 hours and then euthanized. Eyes were removed and 10 µm frozen sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature, rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and counterstained for 5 minutes at room temperature with the nuclear dye Hoechst 33258 (1:10000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Slides were rinsed in PBS, and then examined by fluorescence microscopy (excitation: 543 nm, emission>590 nm) with a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope using a Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 20x/0.75NA objective lens (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). All images were acquired in the frame scan mode with the same exposure time. The excitation wavelength was set at 405 nm for visualization of Hoechst.

Measurement of cone cell density

Cone density was measured as previously described (Komeima et al. 2006; Usui et al. 2009b). Briefly, each mouse was euthanized, and eyes were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the cornea, iris, and lens were removed. A small cut was made at 12:00 for orientation and after 4 radial cuts, equidistant around the circumference, the entire retina was carefully dissected from the eye cup and any adherent retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) was removed. Retinas were placed in PBS containing 1% Tween 20 (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) for 30 minutes at room temperature, incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in 1:200 rhodamine-conjugated peanut agglutinin (PNA; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in PBS containing 1% Tween 20. The retinas were rinsed 3 times for 10 minutes in PBS containing 1% Tween 20, given a final rinse in PBS and flat-mounted. The retinas were examined with a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope with a Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 20x/0.75NA objective lens for high magnification using an excitation wavelength of 543 nm to detect rhodamine fluorescence. Images were acquired in the frame scan mode. Cone cells were counted using high magnification images within four 0.0529 mm2 bins located 1.0 mm superior, inferior, temporal, and nasal from the center of the optic nerve. The investigator was masked with respect to experimental group.

Measurement of outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness

Rd10+/+ mice were randomized to treatment with bilirubin, TUDCA, or their respective controls (HSA or NaHCO3) every 3 days starting at P6. At P30 or P50, mice were euthanized, eyes were removed, the 12:00 position was marked, and 10 µm frozen serial sections were cut parallel to the 12:00 to 6:00 meridian through the optic nerve and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The thickness of the ONL was measured by image analysis at three locations (I1, I2, and I3) between the inferior border of the retina at 6:00 and the optic nerve and at three locations (S1, S2, and S3) between the superior border of the retina at 12:00.as previously described (Komeima et al. 2007).

Recording of ERGs

An Espion ERG Diagnosys machine (Diagnosys LLC, Littleton, MA) was used to record ERGs as previously described (Okoye et al. 2003; Komeima et al. 2006; Komeima et al. 2007; Ueno et al. 2008; Usui et al. 2009b). The mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Pupils were dilated with Midrin P containing 0.5% tropicamide and 0.5% phenylephrine, hydrochloride (Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan). The mice were placed on a pad heated to 39°C, and platinum loop electrodes were placed on each cornea after application of Gonioscopic prism solution (Alcon Labs, Fort Worth, TX). A reference electrode was placed subcutaneously in the anterior scalp between the eyes and a ground electrode was inserted into the tail. The head of the mouse was held in a standardized position in a Ganzfeld bowl illuminator that ensured equal illumination of the eyes. Recordings for both eyes were made simultaneously with electrical impedance balanced. Low background photopic ERGs were recorded at 1.48 log cd-s/m2 under a background of 10 cd/m2. Sixty photopic measurements were taken and the average value was recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were done using unpaired Student’s t-test or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

BALB/c mice treated with bilirubin or TUDCA showed significant resistance to light toxicity

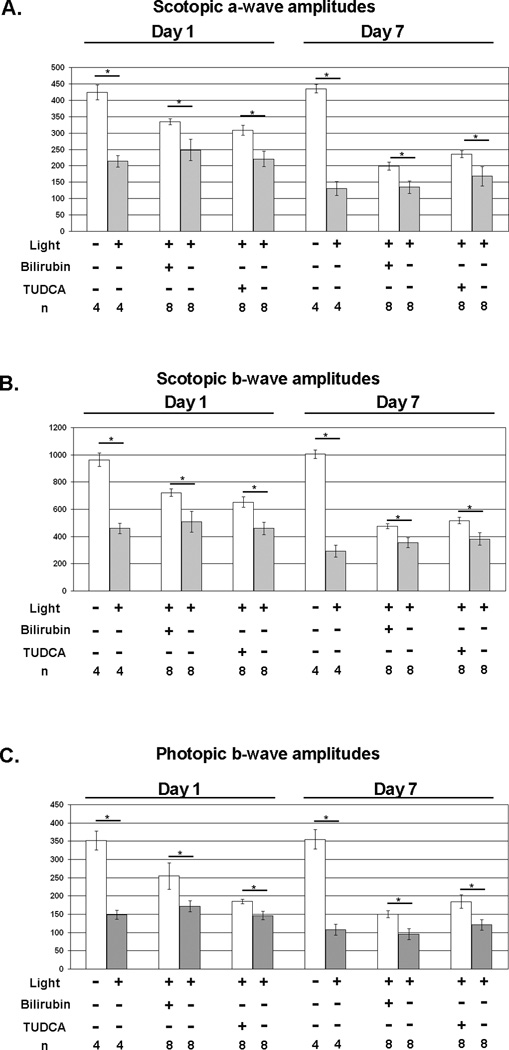

Exposure of albino BALB/c mice to intense light for 8 hours causes photoreceptor degeneration due to oxidative damage (Noell and Albrecht 1971; Li et al. 1985; Tanito et al. 2002). One day after light exposure, there was a marked reduction in rod photoreceptor function measured by scotopic a- and b-wave amplitudes and cone photoreceptor function measured by photopic b-wave amplitudes in untreated BALB/c mice (Figure 1A). Compared to mice treated with the respective vehicles (HSA or NaHCO3), mice treated with 5 mg/kg of bilirubin or 500 mg/kg of TUDCA had significantly greater mean scotopic a- and b-wave amplitudes, and photopic b-wave amplitudes. The reduction in retinal function was even greater 7 days after light exposure and was partially prevented by treatment with bilirubin or TUDCA.

Figure 1. Bilirubin and TUDCA reduce loss of retinal function due to constant light exposure in BALB/c mice.

BALB/c mice were given subcutaneous injections of 5 mg/kg of bilirubin, 500 mg/kg of TUDCA, or corresponding vehicle 24 and 1 hour before constant exposure to 5,000 lux of white light for 8 hours and then returned to a 12 hour/12 hour normal intensity light/dark cycle. Some mice were not exposed to constant light to serve as controls. Scotopic and photopic electroretinograms (ERGs) were done 1 and 7 days after light exposure. The bars show mean (±SEM) scotopic a-wave (A) and b-wave (B) amplitudes recorded after a flash intensity of 25 cd·sec/m2 and mean (±SEM) photopic b-wave amplitudes (C) recorded after a flash intensity of 25 cd·sec/m2 with a background light intensity of 30 cd·sec/m2. Compared to their corresponding vehicle (HSA or NaHCO3) controls, mice treated with bilirubin or TUDCA had significantly higher scotopic a-wave (A), scotopic b-wave (B), and photopic b-wave amplitudes at 1 and 7 days after light exposure.

*p<0.05 by unpaired student t-test for difference between treated mice exposed to light toxicity and the respective vehicle-treated control exposed to light toxicity.

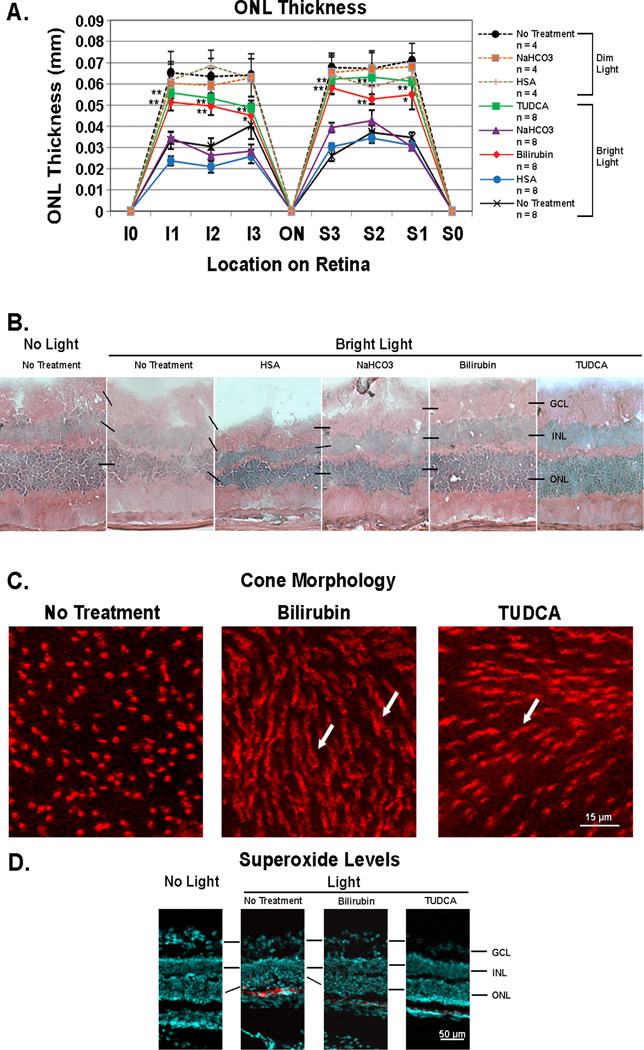

The ONL contains only the nuclei of rods and cones and therefore the thickness of the ONL provides an assessment of the number of photoreceptors at that location in the retina. Since cones comprise only one row of nuclei and the remainder of the ONL is comprised of rods, thinning of the ONL is essentially an indication of rod cell death, but since the ONL thickness varies at different locations in the retina, comparisons between mice must be done at identical locations. Seven days after exposure to bright light (5,000 lux) for 8 hours, the mean ONL thickness was significantly greater in 6 different locations of the retina in mice treated every 3 days with 5 mg/kg of bilirubin or 500 mg/kg of TUDCA compared to mice treated with the corresponding vehicle (HSA or NaHCO3) or untreated mice (Figure 2A). Representative sections from the S1 location for each of the treatment groups is shown in Figure 2B and illustrates that compared to retinas from the three different control groups, those from bilirubin- or TUDCA-treated mice showed thicker ONLs and better tissue preservation. BALB/c mice injected with 5 mg/kg of bilirubin or 500 mg/kg of TUDCA and not exposed to light (n=4 for each) showed no difference in ONL thickness or appearance of the retina compared to untreated mice (data not shown). In light exposed mice, cone cell density was not significantly different in untreated, control mice compared to those treated with bilirubin or TUDCA (n=3 for each, data not shown), but untreated mice showed loss of cone outer segments and flattening of inner segments (Figure 2C, left panel), while mice treated with bilirubin (middle panel) or TUDCA (right panel) showed preservation of cone inner and outer segments (arrows).

Figure 2. Bilirubin and TUDCA reduce rod cell death, loss of cone outer segments, and accumulation of superoxide radicals after constant light exposure in BALB/c mice.

Twenty-four and again one hour prior to 8 hours of constant exposure to 5,000 lux of white light, BALB/c mice were given subcutaneous injections of bilirubin (5 mg/kg) or TUDCA (500 mg/kg), or no injections and then returned to a 12 hour/12 hour normal intensity light/dark cycle. For comparison, dim-light control mice were given each of the above treatments or no treatment and maintained in normal cyclic light. After 7 days some mice were euthanized and eyes were used for measurement of outer nuclear layer thickness (ONL) on serial ocular sections or retinas were dissected intact and stained with rhodamine-labeled peanut agglutinin (PNA) to visualize cones. Other mice were given two intraperitoneal injections of hydroethidine (20 mg/kg) 30 minutes apart 18 hours prior to death so that superoxide radicals could be visualized in ocular sections. (A) The points show mean (±SEM) ONL thickness at three locations (I1, I2, and I3) between the inferior border of the retina at 6:00 (I0) and the optic nerve (ON) and at three locations (S1, S2, and S3) between the superior border of the retina at 12:00 (S0) and the ON. At all six locations, the mean ONL thickness was significantly greater for bilirubin-treated or TUDCA-treated mice compared to respective vehicle-treated (HSA or NaHCO3) mice (*p<0.05; **p<0.01 by unpaired student t-test for difference from respective vehicle-treated control). There was no difference among dim-light controls including mice treated with bilirubin or TUDCA for which data are not shown. (B) Representative sections from the S1 location show thinning of the ONL and vacuoles in the inner retina of light-exposed mice given no treatment or treated with human serum albumin (HSA) or NaHCO3. In contrast light-exposed mice treated with bilirubin or TUDCA showed thick ONLs and less disruption of the retina. (C) Fluorescence microscopy of retinal flat mounts 0.5 mm superior to the optic nerve showed loss of outer segments and flattening of inner segments of cones in untreated light-exposed mice, whereas inner and outer segments were preserved in bilirubin- and TUDCA-treated mice. Observations were made in three mice from each group and these images are representative. (D) Eighteen hours after injection of hydroethidine, there was strong fluorescence indicating the presence of superoxide radicals in the outer retina of untreated light-exposed mice, but none in the retinas of bilirubin- or TUDCA-treated light-exposed mice or mice that were not exposed to constant light (no light).

In the presence of superoxide radicals, hydroethidine is converted to ethidium which binds DNA and fluoresces. After intraperitoneal injection of hydroethidine, there was no fluorescence in the retina of mice that were not exposed to bright light, but there was intense fluorescence in the photoreceptors of mice 7 days after exposure to bright light indicating the presence of many more superoxide radicals (Figure 2D). The fluorescence was eliminated in light-exposed mice treated with bilirubin or TUDCA indicating effective scavenging of superoxide radicals.

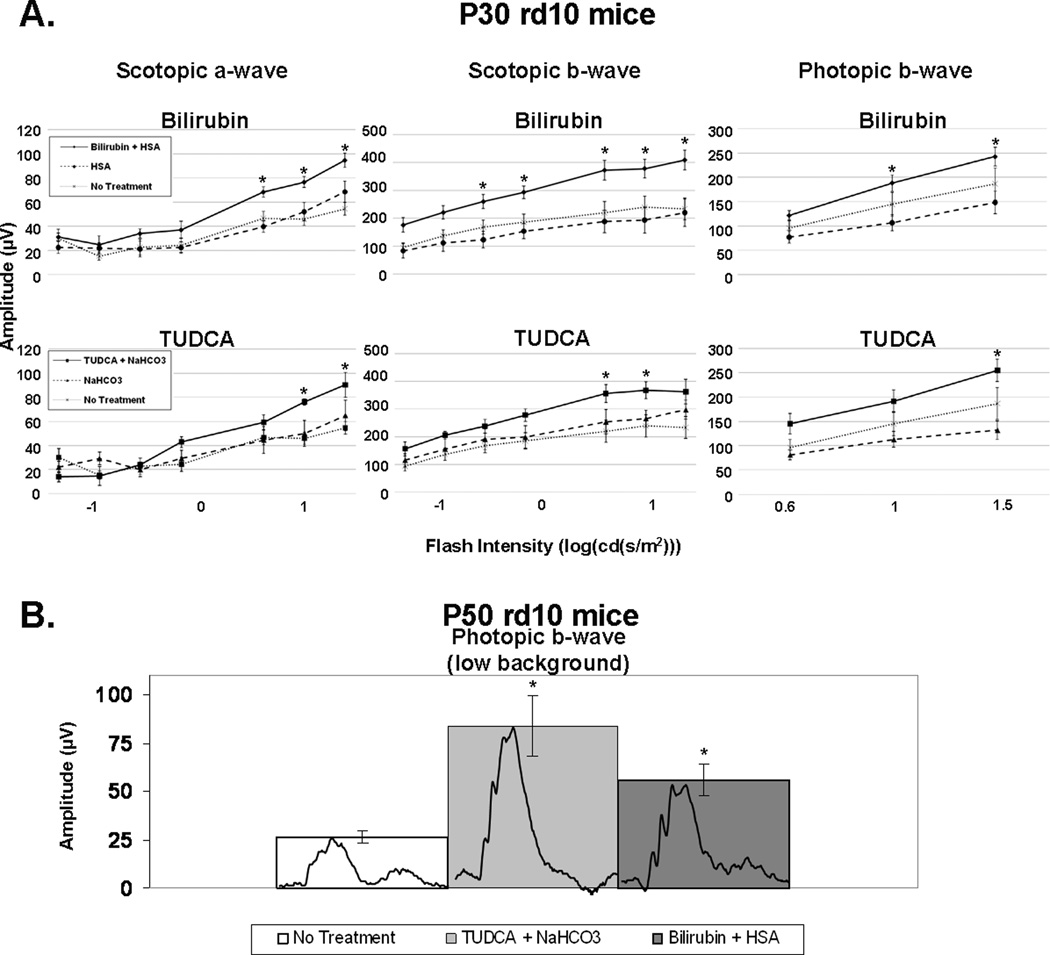

Treatment with bilirubin or TUDCA slows cone photoreceptor death in rd10+/+ mice

In rd10+/+ mice, a missense mutation in exon 7 of the Pde6b gene results in rod photoreceptor cell death between P18 and P30 (Chang et al. 2002; Chang et al. 2007; Gargini et al. 2007). Once there is substantial reduction in the number of rods, cones and remaining rods undergo progressive oxidative damage, which accelerates the death of the remaining rods and causes cone cell death over several weeks (Komeima et al. 2007). Rd10+/+ mice were given subcutaneous injections of 5 mg/kg of bilirubin or 500 mg/kg of TUDCA every three days starting at postnatal day (P) 6. At P30, mean scotopic a- and b-wave amplitudes, and photopic b-wave amplitudes were significantly greater in mice that had been treated with bilirubin or TUDCA compared to mice treated with the corresponding vehicle (Figure 3). At P50, scotopic ERGs were extinguished in all mice indicating complete loss of rod cell function (data not shown). Compared to untreated rd10+/+ mice, those treated with 5 mg/kg of bilirubin or 500 mg/kg of TUDCA every three days had greater preservation of cone cell function as indicated by mean low background (1.0 log (cd·s/m2)) photopic b-wave amplitudes that were 2- to 3-fold higher (Figure 3B, p= 0.037; p=0.029 respectively).

Figure 3. Bilirubin and TUDCA slowed the decline of photoreceptor function in rd10/rd10 mice.

Rd10/rd10 mice were given subcutaneous injections of bilirubin (5 mg/kg) or its HSA vehicle, TUDCA (500 mg/kg) or its NaHCO3 vehicle, or no injection every 3 days starting at postnatal day (P) 6. Scotopic and photopic electroretinograms (ERGs) were performed at P30 and P50. The bars show mean (±SEM) ERG amplitudes. (A) At P30, scotopic a-wave amplitudes were significantly higher for bilirubin (n=10) compared to its vehicle (n=8) at the three highest stimulus intensities and TUDCA (n=6) was significantly higher at the two highest stimulus intensities compared to its vehicle (n=6). Scotopic b-wave amplitudes show a significant difference for bilirubin compared to its vehicle at the five highest stimulus intensities and TUDCA compared to its vehicle at two of the highest stimulus intensities. Photopic b-wave amplitudes at P30 show a significant difference for bilirubin compared to its vehicle at the two highest stimulus intensities and TUDCA compared to its vehicle at the highest stimulus intensity. There was no statistically significant difference between the bilirubin-treated mice and the TUDCA-treated mice at any stimulus intensity. There was no significant difference between any of the three control groups (HSA, NaHCO3, and no injection) at any stimulus intensity. *p<0.05 by unpaired student t-test for difference between treated mice and their respective vehicle-treated control group. (B) Photopic b-wave ERGs with low background light (10 cd*s/m2) at P50 show a significant difference for rd10/rd10 mice injected with either bilirubin (n=8), or TUDCA (n=6), compared to rd10/rd10 control mice (n=4) that received no injection. Representative wave forms are shown (inset) for the non-injected, bilirubin-treated, and TUDCA-treated rd10/rd10 mice. There was no significant difference between the HSA or NaHCO3 vehicle-treated rd10/rd10 mice compared to the rd10/rd10 mice that received no injection. *p<0.05 for difference from untreated control by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

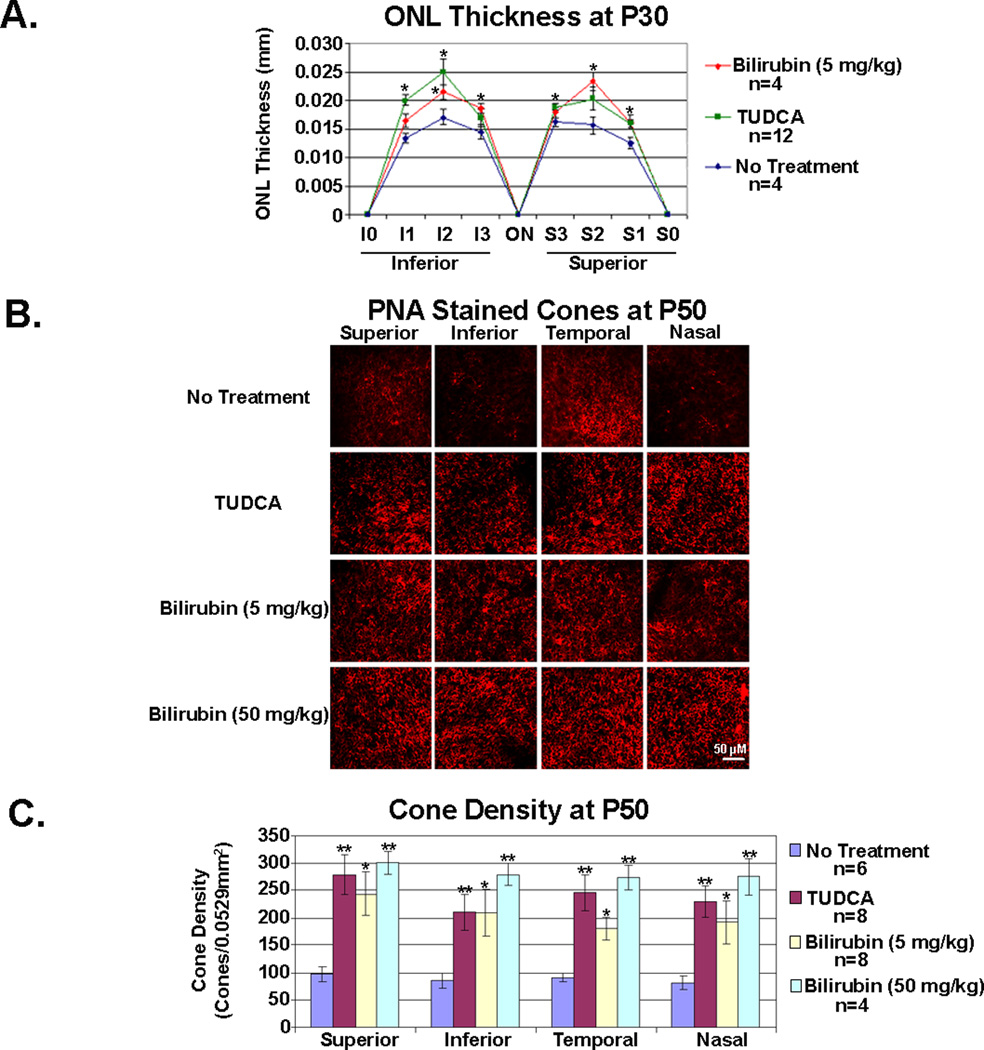

At P30, compared to untreated rd10+/+ mice, those treated with 5 mg/kg of bilirubin showed a significantly thicker ONL in 4 of 6 locations, and those treated with 500 mg/kg of TUDCA showed a significantly thicker ONL in 3 of 6 locations. At P50, retinal flat mounts stained with rhodamine-labeled PNA, showed fairly well-preserved cone densities in rd10+/+ mice treated with 500 mg/kg of TUDCA, 5 mg/kg of bilirubin, or 50 mg/kg of bilirubin, compared to untreated mice (Figure 4B). Image analysis confirmed that mice treated with TUDCA or either dose of bilirubin had significantly higher cone density in all 4 quadrants of the retina than untreated mice (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Bilirubin and TUDCA slow rod and cone cell death in rd10/rd10 mice.

Rd10/rd10 mice were given subcutaneous injections of 5 or 50 mg/kg of bilirubin in vehicle containing human serum albumin (HSA) as a carrier or HSA alone or 500 mg/kg TUDCA or its vehicle (NaHCO3) every three days starting at postnatal day (P) 6. At P30, outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness was measured at 6 locations in each as described in the legend to Figure 2 and Methods (A). Compared to their corresponding vehicle controls (HSA or NaHCO3), the mean (±SEM) ONL thickness was significantly greater in 3 of 6 locations in bilirubin-treated mice and in 4 of 6 locations in TUDCA-treated mice. At P50, cone density was measured on peanut agglutinin-stained retinal flat mounts as described in Methods. Compared to untreated mice, those treated with TUDCA or either of the two doses of bilirubin showed significantly greater mean (±SEM) cone density in each of the 4 quadrants of the retina (B and C).

*p<0.05;**p<0.01 for difference from untreated control by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

There is substantial evidence indicating that bilirubin functions as part of the endogenous antioxidant defense system and elevated serum levels protect vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress and reduce the risk of atherosclerosis (Ishizaka et al. 2001; Vitek et al. 2002; Djousse et al. 2003; Novotny and Vitek 2003). The effects in the nervous system are more complex. Increased serum bilirubin levels protect distinct populations of neurons from ischemia-reperfusion injury, but some neurons are susceptible to bilirubin-induced damage and elevation of serum bilirubin in infants, particularly when conditions do not favor albumin binding, can cause permanent damage to the basal ganglia, a disease state called kernicterus (Ostrow et al. 2004; Wennberg et al. 2006). In this study, we have demonstrated that retinal photoreceptors, a highly specialized type of neuron, are protected against the damaging effects of excessive light stimulation by systemic injections of bilirubin with HSA. Excessive light stimulation increases levels of all-trans retinal which is highly reactive and readily generates ROS. Light damage can be reduced by directly targeting all-trans retinal (Maeda et al. 2009) or by providing antioxidants that scavenge the ROS that are generated (Li et al. 1985; Tanito et al. 2002). Bilirubin acts to reduce the number of superoxide radicals in light-exposed retinas. Injections of 5 or 50 mg/kg of bilirubin every 3 days significantly reduced cone cell death in the rd10+/+ model of RP as has been seen with other antioxidants (Komeima et al. 2006; Komeima et al. 2007). Doses of bilirubin higher than 50 mg/kg caused hair loss and could not be continued, but did not cause evidence of retinal damage. Thus, increased serum levels of bilirubin protect rods and cones from oxidative damage.

TUDCA is another constituent of bile that has previously been shown to provide benefit from excessive light exposure in models of RP (Boatright et al. 2006; Phillips et al. 2008). We have confirmed those findings and have demonstrated that TUDCA acts by reducing oxidative stress. Although high doses of TUDCA are required, the effects are similar to those seen with bilirubin. For both bilirubin and TUDCA, the predominant effect in rd10+/+ mice is to preserve cone cell function and structure; the effect on rod survival is modest and transient. This is consistent with effects of other antioxidants (Komeima et al. 2007; Usui et al. 2009a) and suggests that other mechanisms in addition to oxidative stress play a major role in rod cell death in rd10 mice, but it is a major factor leading to the demise of cones.

The antioxidant-induced reduction of cone cell death in models of RP suggests that an optimized antioxidant formulation could provide benefit in patients with RP and a clinical trial should be considered. However, design of such a trial is difficult because of variable rates of progression among RP patients, even those with the same mutation, presumably due to differences in genetic background and environmental exposures. Considering the variability and the relatively slow rate of progression in most patients, a very large study with a 2 or 3 year endpoint would be required to have a chance of identifying a treatment benefit. However, our findings suggest an alternative strategy to test the hypothesis that cones die from oxidative damage in patients with RP before embarking on an expensive and long interventional trial. Approximately 3–17% of the population (depending upon ethnicity) have Gilbert’s syndrome in which there is modest elevation of serum bilirubin due to a mutation in the promoter region of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase the gene product of which is involved in conjugation of bilirubin facilitating its excretion from the body (Fertrin et al. 2002). Bilirubin in serum is noncovalently bound to HSA which functions as its physiologic carrier, analogous to our experimental paradigm in which HSA was given in combination with albumin. Patients with Gilbert’s syndrome show protection against diseases in which oxidative stress is involved (Vitek et al. 2002; Novotny and Vitek 2003; Bulmer et al. 2008; Schwertner and Vitek 2008). Since it is a relatively common condition, it may be possible to determine if patients with RP and Gilbert’s syndrome have slower disease progression than a cohort of RP patients that are similar but have normal serum bilirubin levels. If there is an inverse correlation between serum bilirubin levels and progression of disease in patients with RP, this would increase motivation for an interventional trial, and provide an important baseline feature that should be stratified. The implications regarding the findings with TUDCA are also important. It is inexpensive, well tolerated, and may have a similar safety profile as the FDA approved non-taurine-conjugated analog UDCA. Therefore, TUDCA is a good candidate for inclusion in an antioxidant test regimen.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a grant from Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB), Gaithersburg, MD, NIH Grants EY015025-03 (Sung), C-NP-0707-0419-JHU05 (Sung), and R01 EY05951 (Campochiaro), and a grant from Knights Templar Eye Foundation (Sung). Shinichi Usui was supported by a Bausch and Lomb Japan Vitreoretinal Research Fellowship and The Osaka Medical Research Foundation for Incurable Diseases. PAC is the George S. and Dolores Dore Eccles Professor of Ophthalmology and Neuroscience.

Abbreviations

- TUDCA

tauroursodeoxycholic acid

- IP

intraperitoneal

- ERGs

electroretinograms

- ONL

outer nuclear layer

- P

postnatal day

- RP

retinitis pigmentosa

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- HO1

heme oxygenase 1

- HO2

heme oxygenase 2

- HSA

human serum albumin

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RPE

retinal pigmented epithelium

- PNA

peanut agglutinin

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

Footnotes

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

References

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aherne A, Kennan A, Kenna PF, McNally N, Lloyd DG, Alberts IL, Kiang A-S, Humphries MM, Ayuso C, Engel PC, Gu JJ, Mitchell BS, Farrar GJ, Humphries P. On the molecular pathology of neurodegeneration in IMPDH1-based retinitis pigmentosa. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:641–650. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright JH, Moring AG, McElroy C, Phillips MJ, Do VT, Chang B, Hawes NL, Boyd AP, Sidney SS, Stewart RE, Minear SC, Chaudhury R, Ciavatta VT, Rodriguez CM, Steer CJ, Nickerson JM, Pardue MT. Tool form ancient pharmacopoeia prevents vision loss. Mol. Vis. 2006;12:1706–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botla R, Spivey JR, Aguilar H, Bronk S, Gores GJ. Ursodeoxycholate (UDCA) inhibits the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition induced by glycochenodeoxycholate: a mechanism of UDCA cytoprotection. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;272:930–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulmer AC, Blanchfield JT, Toth I, Fassett RG, Coombes JS. Improved resistance to serum oxidation in Gilbert's syndrome: a mechanism for cardiovascular protection. Artherosclerosis. 2008;199:390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurda RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR. Retinal degeneration mutants in the mouse. Vision Res. 2002;42:517–525. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Hawes NL, Pardue MT, German AM, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Rengarajan K, Boyd AP, Sidney SS, Phillips MJ, Stewart RE, Chaudhury R, Nickerson JM, Heckenlively JR, Boatright JH. Two mouse retinal degenerations caused by missense mutations in the beta-subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase gene. Vision Res. 2007;47:624–633. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Shi G, Concepcion FA, Xie G, Oprian D, Chen J. Stable rhodopsin/arrestin complex leads to retinal degeneration in a transgenic mouse model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:11929–11937. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3212-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio CA, Millican CL, Allen KA, Kalina RE. Aging of the human photoreceptor mosaic: evidence for selective vulnerability of rods in central retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993;34:3278–3296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djousse L, Rothman KJ, Cupples LA, Levy D, Ellison RC. Effect of serum albumin and bilrubin on the rik of myocardial infarction (the Framingham Offspring Study) Am. J. Cardiol. 2003;91:485–488. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore S, Takahashi M, Ferris CD, Hester LD, Guastella D, Snyder SH. Bilirubin, formed by activation of heme oxygenase-2, protects neurons against oxidative stress injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999a;96:2445–2450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore S, Goto S, Sampei K, Blackshaw S, Hester LD, Ingi T, Sawa A, Traystman RJ, Koehler RC, Snyder SH. Heme oxygenase-2 acts to prevent neuronal death in brain cultures and following transient cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2000;99:587–592. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore S, Sampei K, Goto S, Alkayed NJ, Guastella D, Blackshaw S, Gallagher M, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD, Koehler RC, Snyder SH. Heme oxygenase-2 is neuroprotective in cerebral ischemia. Mol. Med. 1999b;5:656–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertrin KY, Goncalves MS, Saad ST, Costa FF. Frequencies of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 (UGT1A1) gene promoter polymorphisms among distinct ethnic groups from Brazil. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002;108:117–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargini C, Terzibasi E, Mazzoni F, Strettoi E. Retinal organization in the retinal degeneration 10 (rd10) mutant mouse: A morphological and ERG study. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;500:222–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.21144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuman D, Bajaj R. Ursodeoxycholate conjugates protect against disruption of cholesterol-rich membranes by bile salts in primary primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1333–1341. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa J, Reeves PJ, Klein-Seetharaman J, Davidson F, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: Further elucidation of the role of the intradiscal cysteines, Cys-110, -185, and -187, in rhodopsin folding and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1932–1935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illing ME, Rajan RS, Bence NF, Kopito RR. A rhodopsin mutant linked to autosomal dominant RP is prone to aggregate and interacts with the ubiquitin proteasome system. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:34150–34160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Takahashi E, Yamkado M, Hashimoto H. High serum bilirubin level is inversely associated with the presence of carotid plaque. Stoke. 2001;32:581–583. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.580-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komeima K, Rogers BS, Campochiaro PA. Antioxidants slow photoreceptor cell death in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;213:809–815. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komeima K, Rogers BS, Lu L, Campochiaro PA. Antioxidants reduce cone cell death in a model of retinitis pigmentosa. Proc. Natil. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11300–11305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604056103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komeima K, Usui S, Shen J, Rogers BS, Campochiaro PA. Blockade of neuronal nitric oxide synthase reduces cone cell death in a model of retinitis pigmentosa. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:905–912. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs MP, Holden DC, Joshi P, Clark CLI, Lee AH, Kaushal S. Molecular mechanisms of rhodopsin retinitis pigmentosa and the efficacy of pharmacologic rescue. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;395:1063–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid "mechanisms of action and clinical use in hepatobiliary disorders". J Hepatol. 2001;35:134–146. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z-Y, Tso MOM, Wang H, Organisciak DT. Amelioration of photic injury in rat retina by ascorbic acid: a histopathologic study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1985;26:1589–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Lyubarsky A, Skalet JH, Pugh EN, Pierce EA. RP1 is required for the correct stacking of outer segment discs. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:4171–4183. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llesuy SF, Tomaro ML. Heme oxygenase and oxidative stress. Evidence of involvement of bilirubin as physiological protector aganist oxidative damage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1223:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Maeda T, Golczak M, Chou S, Desai A, Hoppel CL, Matsuyama S, Palczewski K. Involvement of all-trans-retinal in acute light-induced retinopathy of mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:15173–15183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900322200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noell WK, Albrecht R. Irreversible effect of visible light on the retina: role of vitamin A. Science. 1971;172:72. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3978.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny L, Vitek L. Inverse relationship between serum bilirubin and atherosclerosis in men: a meta-analysis of published studies. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003;228:568–571. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0322805-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoye G, Zimmer J, Sung J, P G, Deering T, Nambu N, Hackett SF, Melia M, Esumi N, Zack DJ, Campochiaro PA. Increased expression of BDNF preserves retinal function and slows cell death from rhodopsin mutation or oxidative damage. J. Neuosci. 2003;23:4164–4172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04164.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow JD, Pascolo L, Brites D, Tiribelli C. Molecular basis of bilirubin neurotoxicity. Trends Mol. Med. 2004;10:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MJ, Walker TA, Choi HY, Faulkner AE, Kim MK, Sidney SS, Boyd AP, Nickerson JM, Boatright JH, Pardue MT. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid preservation of photoreceptor structure and function in the rd10 mouse through postnatal day 30. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49:2148–2155. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues CMP, Fan G, Wong PY, Dren BT, Steer CJ. Ursodeoxycholic acid may inhibit deoxycholic acid-induced apoptosis by modulating mitochondrial transmembrane potential and reactive oxygen species production. Mol. Med. 1998;4:165–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwertner HA, Vitek L. Gilbert syndrome, UGT1A1*28 allele, and cardiovascular disease risk: possible protective effects and therapeutic applications of bilirubin. Atherosclerosis. 2008;198:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Yan X, Dong A, Petters RM, Peng Y-W, Wong F, Campochiaro PA. Oxidative damage is a potential cause of cone cell death in retinitis pigmentosa. J. Cell. Physiol. 2005;203:457–464. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Antioxidant activity of albumin-bound bilirubin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987a;84:5918–5922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, McDonagh AF, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiologic importance. Science. 1987b;235:1043–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.3029864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam B, Moritz OI. Characterization of rhodopsin P23H-induced retinal degeneration in a Xenopus laevis model of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:3234–3241. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanito M, Nishiyama A, Tanaka T, Mansutani H, Nakamura H, Yodi J, Ohira A. Change of redox status and modulation by thiol replenishment in retinal photooxidative damage. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:2392–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Pease ME, Wersinger DMB, Masuda T, Vinores SA, Licht T, Zack DJ, Quigley H, Keshet E, Campochiaro PA. Prolonged blockade of VEGF family members does not cause identifiable damage to retinal neurons or vessels. J. Cell. Physiol. 2008;217:13–22. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui S, Oveson BC, Lee SY, Jo YJ, Yoshida T, Miki A, Miki K, Iwase T, Lu L, Campochiaro PA. NADPH oxidase plays a central role in cone cell death in retinitis pigmentosa. J. Neurochem. 2009a;110:1028–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui S, Komeima K, Lee SY, Jo Y-J, Ueno S, Rogers BS, Wu Z, Shen J, Lu L, Oveson BC, Rabinovitch PS, Campochiaro PA. Increased expression of catalase and superoxide dismutase 2 reduces cone cell death in retinitis pigmentosa. Molec. Ther. 2009b;17:778–786. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitek L, Jirsa M, Brodanova M, Kalab M, Marecek Z, Danzig V, Novotny L, Kotal P. Gilbert syndrome and ischemic heart disease: a protective effect of elevated bilirubin levels. Atherosclerosis. 2002;160:449–456. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg RP, Ahlfors CE, Bhutani VK, Johnson LH, Shapiro SM. Toward understanding kernicterus: a chanllenge to improve the management of jaundiced newborns. Pediatrics. 2006;117:474–485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu DY, Cringle SJ, Su EN, Yu PK. Intraretinal oxygen levels before and after photoreceptor loss in the RCS rat. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:3999–4006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]