Abstract

Exogenous gene delivery to alter the function of the heart is a potential novel therapeutic strategy for treatment of cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure (HF). Before gene therapy approaches to alter cardiac function can be realized, efficient and reproducible in vivo gene techniques must be established to efficiently transfer transgenes globally to the myocardium. We have been testing the hypothesis that genetic manipulation of the myocardial β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) system, which is impaired in HF, can enhance cardiac function. We have delivered adenoviral transgenes, including the human β2-AR (Adeno-β2AR), to the myocardium of rabbits using an intracoronary approach. Catheter-mediated Adeno-β2AR delivery produced diffuse multichamber myocardial expression, peaking 1 week after gene transfer. A total of 5 × 1011 viral particles of Adeno-β2AR reproducibly produced 5- to 10-fold β-AR overexpression in the heart, which, at 7 and 21 days after delivery, resulted in increased in vivo hemodynamic function compared with control rabbits that received an empty adenovirus. Several physiological parameters, including dP/dtmax as a measure of contractility, were significantly enhanced basally and showed increased responsiveness to the β-agonist isoproterenol. Our results demonstrate that global myocardial in vivo gene delivery is possible and that genetic manipulation of β-AR density can result in enhanced cardiac performance. Thus, replacement of lost receptors seen in HF may represent novel inotropic therapy.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease accounts for nearly 40% of all deaths annually in the United States. Advances in medical treatments have dramatically reduced the overall mortality rate due to heart disease; however, death due to chronic heart failure (HF) continues to rise, and effective therapy has been elusive (1). Therefore, novel therapeutic approaches for treating the failing heart are of interest. The β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) signaling system, which mediates the inotropic and chronotropic effects of the sympathetic transmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine, plays a critical role in the regulation of cardiac performance, which is particularly important under pathological circumstances. Multiple lines of experimental evidence indicate fundamental alterations in the myocardial β-AR system that both precede and accompany the development of HF (2–4). In failing human myocardium, there is a 50% decrease in β-ARs that is specific for the β1-subtype, whereas remaining receptors (β1 and β2) are functionally uncoupled (5, 6). Functional uncoupling of myocardial β-ARs in human HF may be due to elevated levels of the β-AR kinase (βARK1) that has been shown to be increased in human HF (6). Drugs targeting adrenergic signaling, including β-agonists for acute situations and β-blockers for chronic therapy, have been at the forefront of conventional therapy for HF; however, administration of β-AR agonists to stimulate inotropy in the failing heart have inherently limited efficacy, partly because of the specific reduction in β-AR targets (7).

Gene transfer in vivo to the heart has significant therapeutic potential for several cardiovascular disorders. The delivery of a transgene encoding a β-AR to the myocardium is an attractive strategy for improving cardiac function in HF by replacing lost receptors. In fact, transgenic mouse technology has already demonstrated that myocardial overexpression of β2-ARs results in mice with significantly enhanced cardiac function without significant negative effects (8, 9). Moreover, we have recently shown that adenoviral-mediated β2-AR gene transfer to cultured ventricular myocytes isolated from rabbit hearts paced into HF restores β-AR signaling to normal levels (10).

Before gene therapy approaches to alter cardiac function can be realized, efficient and reproducible in vivo gene delivery to the heart must be established and optimized. Recombinant adenoviruses appear to offer the most advantages for myocardial gene transfer. Numerous reports have described attempts at direct injection of adenoviral constructs containing marker genes into the myocardium (11–13), but limitations of this technique include low efficiency of infection and insufficient volume of myocardial expression to alter cardiac function. In addition, there have been attempts to deliver adenoviral transgenes to the myocardium through the coronary arteries (14–16). The purpose of this study was to develop an intracoronary artery delivery method for efficient and reproducible global gene transfer to the rabbit myocardium. In addition, we wanted to test the hypothesis that overexpression of β2-ARs can alter both biochemical and in vivo cardiac function in the rabbit.

Methods

Adenoviral transgenes.

The adenoviral backbone used for the construction of the vectors containing the human β2-AR transgene (Adeno-β2AR) and a cytoplasmic-expressing β-galactosidase transgene (Adeno-βGal) was a replication-deficient first-generation type V adenovirus with deletions of the E1 and E3 genes as we have described previously (10, 17). Large-scale preparations of these adenoviruses were purified from infected EBNA-transfected 293 cells (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, California, USA) as described (10, 17).

In vivo intracoronary delivery of adenoviruses.

Animals used in this study were adult male New Zealand white rabbits (1–2 kg). Animals were housed under standard conditions and allowed to feed ad libitum. The Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University Medical Center approved all procedures performed in accordance with the regulations adopted by the National Institutes of Health. Rabbits were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.1 mg/kg), intubated, and mechanically ventilated. Additional ketamine was administered intravenously if necessary during the procedure. A right thoracotomy was performed through the third or fourth intercostal space, and the aortic root was exposed by blunt dissection. A bolus of adenosine (0.75 mg/kg) was delivered to the right ventricular (RV) chamber by a 30-gauge syringe. Immediately, a 25-gauge catheter was inserted through the apical myocardium; the proximal aorta was cross-clamped; and a 1.5-mL bolus of either saline or adenoviral solution was rapidly injected into the left ventricular (LV) chamber. After a clamp time of 40 seconds, aortic flow was restored. When hemodynamic stability was achieved, anatomic closure was performed; the chest was evacuated of residual air using a 16-gauge angiocatheter attached to a syringe; and the animal was extubated when able to breathe spontaneously. The operative mortality associated with the gene delivery procedure was ∼10%. In the different treatment groups, mortality after surgery was ∼20%, with the majority of deaths occurring around postoperative day 2. There were no deaths after postoperative day 7.

Histology.

Hearts were excised, rinsed in PBS, frozen in embedding compound, and stored at –80°C. Specimens were mounted on a freezing microtome, and 10-μm sections were transferred to glass slides pretreated with aminoalkylsilane (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Sections were fixed in 10% formalin for 2 minutes at room temperature and washed in PBS. β-Galactosidase staining was carried out in 2 mmol/L K4Fe(CN)6, 2 mmol/L K3Fe(CN)6, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, and 0.5 mg/mL X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) in PBS (pH 7.4) as described (18). After being stained (30–60 minutes at 37°C), the sections were rinsed in PBS solution and counterstained with eosin. Additional sections were prepared in the same manner and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for assessment of myocardial cellular infiltrates and inflammation.

β2-AR immunohistochemistry.

Frozen myocardial sections were cut at 10 μm for indirect immunofluorescence studies. Sections were rinsed in PBS and then in PBS with 0.05% Triton X-100 (Triton-PBS), blocked with serum diluent (10% goat serum in PBS with 0.1% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide), and then rinsed for 15 minutes in Triton-PBS before overnight incubation at 4°C with a primary rabbit antihuman β2-AR antiserum (1:500 dilution in serum diluent) as we have described (18). The sections were then washed 4 times for 10 minutes in Triton-PBS at room temperature and incubated for 1 hour in FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:50 dilution in serum diluent). After rinsing with PBS, the sections were mounted and photographed (18).

β-AR radioligand binding.

Myocardial membranes were prepared by homogenization of excised hearts in ice-cold lysis buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM EDTA) as described previously (18, 19). Final purified cardiac membranes were suspended at a concentration of 1–2 mg/mL in ice-cold β-AR binding buffer (75 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 12.5 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM EDTA), and receptor binding was performed using the nonselective β-AR ligand [125I]cyanopindolol (18, 19). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 20 μM alprenolol. All assays were performed in triplicate, and receptor density (measured in femtomoles) was normalized to milligrams of membrane protein.

Membrane adenylyl cyclase activity.

Myocardial membranes were prepared as already described here and incubated (20–30 μg of protein) for 15 minutes at 37°C with [α-32P]ATP under basal conditions or in the presence of either 100 μM isoproterenol or 10 mM NaF, and cAMP was quantitated by standard methods that have been described (19).

In vivo hemodynamic measurements.

To evaluate in vivo physiology and contractile function, all animals were sedated with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.1 mg/kg). After local infiltration of 1% lidocaine, venous access was obtained by way of the external jugular vein, and a 2.5 French micromanometer was placed into the LV through the carotid artery. LV pressure was then obtained using custom data acquisition software at a sampling rate of 200 Hz (Physiologic Data Systems Inc., Durham, North Carolina, USA). Data were acquired at baseline and after infusion of isoproterenol at 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 μg/kg/min as we have described (20). The LV pressure data were then analyzed on a VAX/Microsystem II (Digital Equipment Corp., Woburn, Massachusetts, USA) with custom software to derive the maximal and minimal first derivative of the pressure rise (LV dP/dtmax and LV dP/dtmin, respectively), as well as heart rate (HR), peak systolic pressure (SP), and mean ejection pressure. To determine the effect of HR on ventricular function, 6 animals underwent placement of epicardial pacing wires on the right atrium at the time of virus injection.

Myocyte studies.

To determine whether β2-AR overexpression might benefit the failing myocyte, we carried out a study in cultured ventricular myocytes isolated from normal rabbits or rabbits in HF induced by left circumflex coronary artery ligation (21). This model of HF in the rabbit has recently been described by our laboratory to recapitulate several features of the human disease (21). Myocytes were isolated from rabbit hearts as described by us using a Langendorff perfusion technique (10, 17). To assess the effect of β2-AR overexpression on intracellular signaling, cultured myocytes were plated at a density of 1 × 105 per 35-mm well that were precoated with 20 μg/mL of mouse laminin for 1 hour. After 5 hours, the myocytes adhered to the tissue culture plates, and cells were infected with an moi of 300:1 of the adenovirus in 0.5 mL of solution (10, 17). The cells were incubated with the virus for 15 minutes, after which culture media were added back to the plates. Typically, infection of rabbit ventricular myocytes with Adeno-β2AR results in β-AR levels >1 pmol/mg membrane protein (10, 17). Thirty-six hours later, myocytes were labeled overnight in 1.5 μCi/mL [3H]adenine in Medium 199 and then preincubated in MEM with 10 mM HEPES and 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) for 30 minutes. For dose-response studies, different concentrations of isoproterenol were added for 15 minutes, and intracellular cAMP was determined by standard chromatography methods as described (10, 17).

Statistical analysis.

Quantitative data, such as myocardial β-AR density after adenoviral transgene delivery and physiological parameters, are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The difference in the level of myocardial transgene expression and cardiac function between control and adenovirus-treated rabbits was evaluated using a Student’s t test. For physiological and myocyte isoproterenol responses, differences between groups were analyzed using single-factor ANOVA. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In vivo myocardial adenoviral transgene delivery.

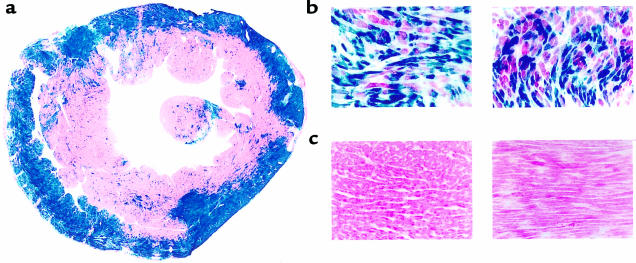

Intracoronary delivery is the most efficient way to deliver adenoviral transgenes globally to the myocardium. To achieve this, we developed a surgical technique in rabbits, whereby a catheter is placed into the LV chamber through the apex of the heart by way of a right thoracotomy. The adenovirus solution in PBS (1.5 mL) is rapidly injected while the aorta is cross-clamped for 40 seconds. This enables all coronary beds to be perfused by the adenovirus. During clamping, the heart visibly blanches, demonstrating a washout of blood and replacement by the viral solution. Before adenovirus delivery, adenosine (0.75 mg/kg) is injected, which serves to slow the heart. To assess myocardial expression of adenoviral transgenes, we delivered either an adenovirus containing a cytoplasmic β-galactosidase marker gene (Adeno-βGal), the cDNA for the human β2-AR (Adeno-β2AR), or no transgene (empty adenovirus [EV]). As shown in Figure 1a, 6 days after Adeno-βGal delivery (1 × 1012 total viral particles [tvp]), global myocardial β-Gal expression is evident by the robust X-Gal staining of both the LV and RV as well as throughout the septum. Although there is an abundance of epicardial expression, transmural penetrance of the β-Gal transgene is clearly evident. With higher magnification, Adeno-βGal–treated hearts reveal that the expression is apparent in individual myocytes (Figure 1b). Control sections of hearts treated with equivalent doses of Adeno-β2AR or EV revealed no specific X-Gal staining (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Expression of β-galactosidase in rabbit hearts after intracoronary in vivo delivery of a recombinant adenovirus. (a) X-Gal staining of a cross-section of a heart taken at midventricular level 6 days after intracoronary delivery of 1 × 1012 tvp of Adeno-βGal. ×3. (b) Representative higher magnification of Adeno-βGal–treated hearts showing myocyte-specific β-Gal expression in cross (left) and longitudinal (right) sections. ×40. (c) Representative sections from hearts injected with EV (left) or Adeno-β2AR (right). ×40.

Adenoviral-mediated myocardial β2-AR overexpression.

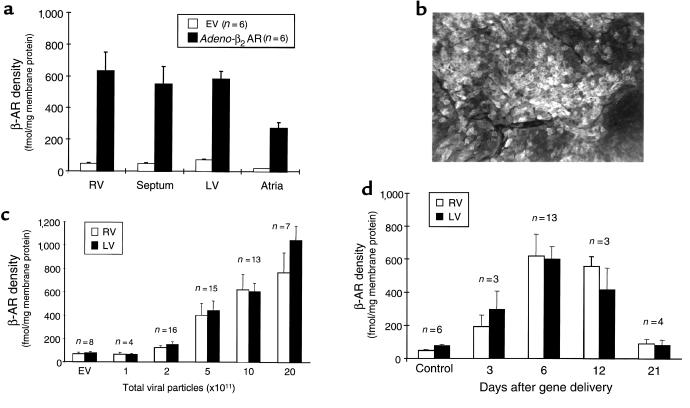

After the demonstration of in vivo global myocardial transgene delivery with Adeno-βGal, we assessed the delivery of the therapeutic transgene, Adeno-β2AR. Similar to Adeno-βGal delivery, β2-AR overexpression, determined by radioligand binding 1 week after Adeno-β2AR intracoronary administration, is global in nature, as demonstrated by robust overexpression in all cardiac chambers — including the septum (Figure 2a). Diffuse β2-AR overexpression is evident throughout the heart in the sarcolemmal membranes of individual myocytes, as demonstrated by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 2b). We also found measurable β-AR overexpression in other tissues, but appreciable levels were limited to the liver and lungs (data not shown), consistent with previous studies (14, 16).

Figure 2.

β-AR overexpression in rabbit hearts after intracoronary delivery of Adeno-β2AR. (a) Total β-AR density in different chambers of rabbit myocardium 6 days after 1 × 1012 tvp of Adeno-β2AR was delivered via intracoronary perfusion. β-AR density after Adeno-β2AR treatment is compared with rabbit hearts that received the same dose of the EV. (b) Representative immunohistochemical detection of expressed human β2-ARs in rabbit LV 6 days after intracoronary delivery of Adeno-β2AR. (c) Dose-dependent myocardial β2-AR overexpression after delivery of increasing doses of Adeno-β2AR. Total β-AR density is shown in the RV and LV compared with myocardial β-AR density after delivery of EV, which did not change from endogenous β-AR levels. (d) Time course of β-AR overexpression in rabbit hearts after delivery of 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-β2AR. All binding values represent the mean ± SEM.

To determine whether β2-AR overexpression depends on the adenoviral dose injected into the rabbit heart, we delivered varying doses of Adeno-β2AR. As shown in Figure 2c, β2-AR overexpression in the ventricles shows a dose dependence, as assessed at 1 week after in vivo gene delivery of Adeno-β2AR. Normal, endogenous β-AR density in rabbit myocardium is ∼75 fmol/mg membrane protein, which was not altered by delivery of the EV (Figure 2c). Significant β2-AR overexpression was seen beginning with 5 × 1011 tvp of Adeno-β2AR, and expression approached 1 pmol/mg membrane protein with 20 × 1011 tvp (Figure 2c). However, there was not a significant increase in β2-AR overexpression between 10 × 1011 and 20 × 1011 tvp of Adeno-β2AR. Furthermore, in preliminary physiological experiments, β2-AR overexpression above 800 fmol/mg membrane protein produced diminished cardiac function, which is probably the result of enhanced inflammation observed with higher doses of adenovirus (see later here). Thus, 5 × 1011 tvp of Adeno-β2AR was chosen as the “therapeutic dose.” Injection of this amount of virus reproducibly results in 5- to 10-fold global myocardial β2-AR overexpression.

A property of adenovirus gene transfer in vivo is the loss of transgene expression, due to several factors inherent in the virus construct itself or in the host animal. To test how long β2-AR transgene overexpression is supported in the heart after in vivo intracoronary delivery, we injected 5 × 1011 tvp of Adeno-β2AR and measured β-AR density at varying time points. As shown in Figure 2d, β2-AR overexpression peaked ∼1 week after gene delivery but was still significantly increased at 12 days. Three weeks after gene delivery, β2-AR overexpression is minimal, which is consistent with the duration of in vivo expression seen by others (14). However, significant overexpression at ∼2 weeks is quite a bit longer than the duration of expression observed in a rat heart transplant model of ex vivo Adeno-β2AR gene transfer (18). Because the major reason for loss of adenoviral transgene expression in vivo is believed to be host immunological responses due to the virus (22, 23), we assessed the degree of inflammation in our hearts histologically. Six days after 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-β2AR or EV delivery by coronary perfusion, there is minor inflammation signified by cellular infiltration in the myocardium, as assessed by H&E staining, compared with saline-injected control rabbits (data not shown); this finding is consistent with previous studies using adenovirus (12, 14).

Effect of β2-AR overexpression on myocardial signaling and function.

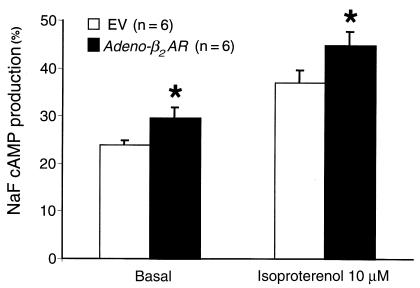

To assess whether the β2-ARs expressed in the myocardium after in vivo intracoronary delivery were functionally coupled, we examined adenylyl cyclase activity in membranes prepared from rabbit hearts injected with either the EV or Adeno-β2AR. Basal adenylyl cyclase activity was measured, as well as activity in response to the β-agonist isoproterenol. As shown in Figure 3, both basal and isoproterenol-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activities were significantly enhanced in hearts overexpressing β2-ARs compared with myocardial membranes prepared from EV-treated rabbits.

Figure 3.

Membrane adenylyl cyclase activity from hearts of Adeno-β2AR–treated rabbits. Membranes were purified from rabbits 6 days after intracoronary delivery of 5 × 1011 tvp of Adeno-β2AR or EV (n = 6 each), and adenylyl cyclase activity was measured under basal conditions and after isoproterenol (10–4 M) or NaF (10 mM). Values shown are the mean ± SEM normalized to the value seen with NaF. Activity in the 2 groups with NaF was not significantly different (data not shown), indicating no postreceptor defects in signaling. *P < 0.05 vs. EV (Student’s t test).

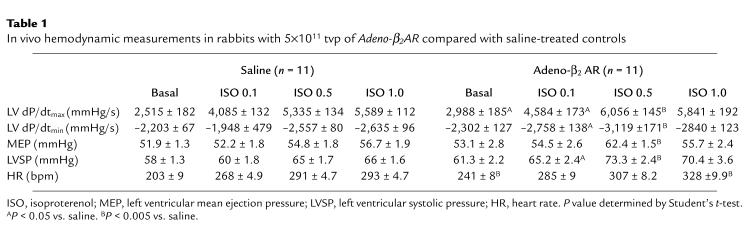

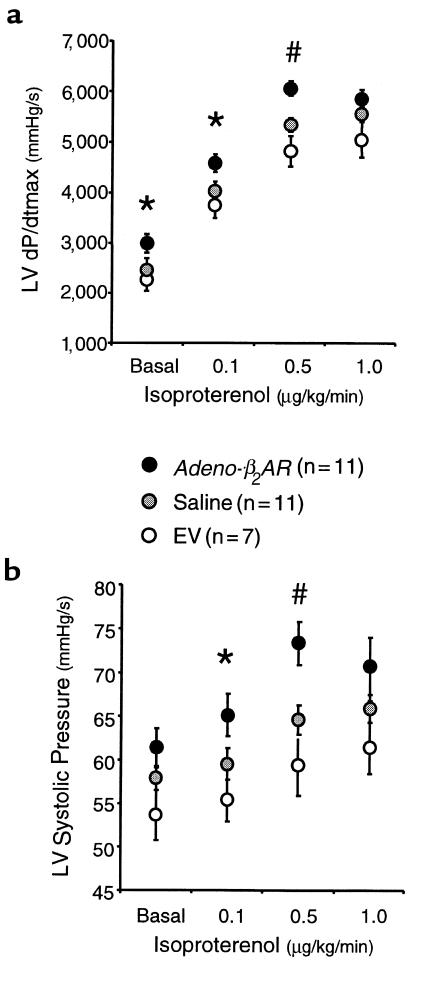

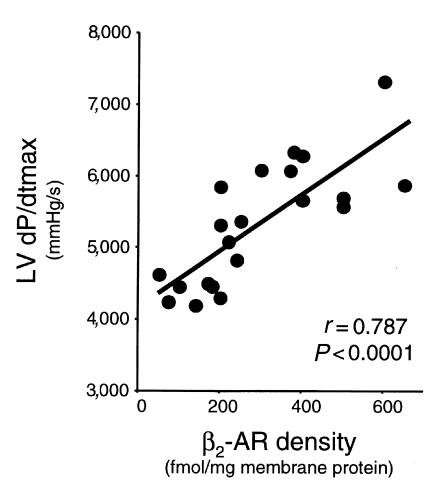

The ultimate goal of this study was to test whether myocardial β2-AR overexpression after in vivo adenovirus delivery by coronary perfusion could alter global heart function. To do this, we evaluated in vivo hemodynamic parameters of cardiac function by way of catheterization of sedated but conscious rabbits. We initially assessed cardiac physiology 6 days after adenovirus administration, which was the time of peak expression (Figure 2d). Rabbits were either injected with saline, EV (5 × 1011 tvp), or Adeno-β2AR (5 × 1011 tvp) as already described here. Measurements were recorded at baseline and after infusion of 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 μg/kg/min of isoproterenol. Physiological measurements of the saline-injected and Adeno-β2AR–treated rabbits are listed in Table 1. Values for LV +dP/dtmax and LV –dP/dtmin as measurements of cardiac contractility and relaxation, respectively, are shown, as are values for the LV mean ejection pressure (MEP), LV systolic pressure (LVSP), and HR. β2-AR overexpression as a result of the intracoronary delivery of Adeno-β2AR leads to significant enhancement of several key hemodynamic measurements (Table 1). At baseline, there was a significant improvement in baseline LV +dP/dtmax in the Adeno-β2AR–treated rabbits that was accompanied by a significant increase in HR (Table 1). After administration of 0.1 and 0.5 μg/kg/min isoproterenol, HR was not significantly increased in Adeno-β2AR–treated rabbits; however, LV +dP/dtmax and LV SP in β2-AR–overexpressing rabbits was significantly enhanced compared with saline-injected controls. LV contractility responses in Adeno-β2AR–, saline-, and EV-treated rabbits are shown graphically in Figure 4a. Figure 4b shows LVSP responses in the same groups. The isoproterenol dose-responses for both of these parameters were significantly enhanced in the Adeno-β2AR group compared with EV-treated rabbits. EV treatment was not significantly different than saline; however, values tended to be lower, as seen in Figure 4, a and b. This could be due to the small level of inflammation that was observed histologically after adenovirus administration. After physiological assessment, all animals were sacrificed to measure their level of β2-AR overexpression. In animals that received 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-β2AR, receptor density ranged from 400 to 700 fmol/mg membrane protein. Within this window of overexpression, there was a significant direct linear relationship between maximum isoproterenol-induced LV +dP/dtmax and β-AR density (Figure 5). This demonstrates that the enhanced cardiac function seen in vivo in these rabbits is the direct result of β2-AR overexpression.

Table 1.

In vivo hemodynamic measurements in rabbits with 5×1011 tvp of Adeno-β2AR compared with saline-treated controls

Figure 4.

In vivo assessment of LV contractile function in rabbits treated with Adeno-β2AR. Cardiac catheterization was performed in conscious sedated rabbits 6 days after intracoronary delivery (1.5 mL in PBS) of either 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-β2AR (n = 11), EV (n = 7), or saline (n = 11) using a high-fidelity micromanometer. Parameters measured include (a) LV +dP/dtmax and (b) LVSP. Shown are the baseline values (as mean ± SEM) and responses to progressive doses of isoproterenol. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.005 vs. saline (Student’s t test). For LV +dP/dtmax and LVSP, isoproterenol responses in the Adeno-β2AR group are significantly different than those in the EV-treated group (P < 0.01, ANOVA).

Figure 5.

Relationship between myocardial β2-AR overexpression and in vivo contractility. Total cardiac β-AR density was plotted against maximal isoproterenol-stimulated LV +dP/dtmax of rabbits treated with Adeno-β2AR. A significant linear relationship was found (t test).

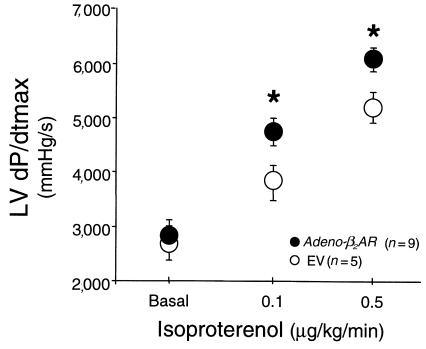

In an additional set of rabbits, we delivered 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-β2AR (n = 9) or EV (n = 5) and assessed in vivo hemodynamics 21 days after gene delivery. Although baseline LV +dP/dtmax was not elevated, responses to isoproterenol were significantly enhanced in the Adeno-β2AR–treated animals compared with the control rabbits that received EV (Figure 6). Interestingly, the levels of β2-AR overexpression seen in these rabbit hearts were minimal compared with what was seen in the animals tested 1 week after gene delivery; however, β-AR density was still significantly higher than endogenous levels in the hearts of EV-treated rabbits (115 ± 12 vs. 79 ± 7 fmol/mg membrane protein; P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

In vivo assessment of LV contractile function (LV +dP/dtmax) in rabbits 21 days after treatment with Adeno-β2AR. Cardiac catheterization was performed in conscious sedated rabbits after intracoronary delivery (1.5 mL in PBS) of either 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-β2AR (n = 9) or EV (n = 5) using a high-fidelity micromanometer. Shown are the baseline values (mean ± SEM) and responses to progressive doses of isoproterenol. *P < 0.05 vs. EV (Student’s t test). Total β-AR density after Adeno-β2AR treatment was 115 ± 12 fmol/mg membrane protein vs. 79 ± 7 in hearts that received the same dose of EV (P < 0.05, Student’s t test).

The results of the physiology measurements indicate that β2-AR overexpression does positively effect global in vivo cardiac performance. However, as HR can affect certain physiological parameters, especially LV +dP/dtmax, we studied 3 additional saline- and Adeno-β2AR–treated rabbits that had atrial pacing wires surgically implanted at the time of gene delivery. LV +dP/dtmax was then assessed in these animals after 6 days, as already described here, at differently paced HRs; importantly, no significant change in LV +dP/dtmax was seen with HRs between 200 and 300 bpm in Adeno-β2AR–treated rabbits.

β2-AR overexpression in failing rabbit myocytes.

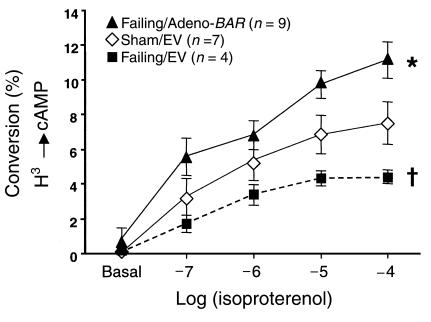

These results suggest that replacing lost β-ARs in HF may be a novel therapeutic strategy to treat the failing heart. To examine whether β2-AR overexpression in failing myocytes might enhance β-AR signaling, we carried out studies using Adeno-β2AR treatment in failing rabbit myocytes. These failing myocytes were isolated from rabbits 21 days after myocardial infarction induced by left circumflex coronary artery ligation (21). In this model of rabbit HF, several features of human HF are recapitulated, including abnormal β-AR signaling (21). Myocytes isolated from infarcted rabbits have abnormal cAMP accumulation in response to β-AR stimulation (21). In Figure 7, we demonstrate that EV-treated ventricular myocytes from infarcted rabbits have attenuated cAMP responses compared with EV-treated myocytes from control (sham-operated) rabbits. However, Adeno-β2AR treatment of myocytes isolated from infarcted rabbits enhances β-AR signaling to levels even greater than control, demonstrating a β-AR signaling rescue in these failing myocytes (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Rescue of attenuated signaling in failing ventricular myocytes by treatment with Adeno-β2AR. Shown is the isoproterenol-induced cAMP production in sham and failing isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes treated with EV or Adeno-β2AR. Failing ventricular myocytes were isolated from rabbit hearts 21 days after left circumflex coronary artery ligation (21). Experiments were performed 36 hours after adenoviral infection and after overnight labeling with 1.5 μCi/mL [3H]adenine (see Methods). The accumulation of intracellular cAMP is expressed as percent conversion from total 3H uptake. The data represent the mean ± SEM of 4–9 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Total responses of the failing/EV group were significantly attenuated compared with sham/EV-treated myocytes (P < 0.05, single-factor ANOVA). Total responses of the failing Adeno-β2AR–treated myocytes were significantly enhanced compared with the failing/EV-treated cells (*P < 0.05, ANOVA).

Discussion

In this study, we present the novel findings that acute global myocardial overexpression of the human β2-AR in rabbits can lead to enhancement of cardiac physiology assessed by conscious in vivo hemodynamics after intracoronary administration of recombinant adenovirus. We have developed a technique for global myocardial transgene delivery in a larger animal species that provides an important in vivo model to study the functional significance of acute transgenesis of the heart. Given the well-characterized deficiencies in myocardial β-AR signaling in chronic human HF (2, 3, 6), our present findings suggest that gene transfer to replace lost β-ARs in failing hearts may have potential for producing therapeutic cardiac inotropy.

Our model of in vivo myocardial gene transfer demonstrates efficient and reproducible global transgene delivery to all chambers of the rabbit heart. This method was developed to ensure that all coronary beds are perfused by the adenoviral solution under pressure so that the myocardium may be globally infected. The method of in vivo global myocardial gene delivery described here has advantages over methods of direct coronary artery catheterization and injection. Percutaneous coronary artery delivery involves administering the virus to a single coronary artery, and transgene expression is limited to the area of the heart supplied by that coronary (14, 15). In contrast, by injection of the adenovirus into the LV cavity while the aorta is cross-clamped, we ensure that all coronary vessels are perfused, which results in transgene expression globally in the heart. While we were completing this study, a similar technique was used in rats, whereby adenovirus was injected into the LV cavity while briefly clamping both the aorta and pulmonary artery (16). However, our rabbit model is unique, as we do not clamp the pulmonary artery and aortic clamp time is considerably longer, which probably contributes to enhanced viral uptake. In the rat study, myocardial overexpression of a phospholamban transgene decreased certain hemodynamic parameters and, thus, did not represent a potential therapy (16). Overexpression of the phospholamban transgene was modest (2- to 3-fold) compared with the 5- to 10-fold overexpression of the β2-AR transgene in the present study, which could possibly be due to the prolonged aortic clamp time and higher adenoviral doses used. In addition, rabbits have slower HRs than rats; these already slow HRs were further reduced by adenosine administration, allowing more adenovirus contact time with the myocardium. Thus, all of these factors probably contribute to the robust global myocardial transgene expression seen in this rabbit model of intracoronary gene delivery, making it possible to examine the potential usefulness of this approach to enhance therapeutically the function of the heart in vivo.

The demonstration that overexpression of β2-ARs between 400 and 700 fmol/mg membrane protein enhances adenylyl cyclase activity in vitro, and several hemodynamic parameters in vivo, is of significance. In this study, both baseline and isoproterenol-stimulated LV +dP/dtmax were enhanced after β2-AR overexpression compared with saline- and EV-treated control rabbits, which were not influenced by HR. Moreover, there was a significant direct relationship between β2-AR overexpression and contractility at 6 days after gene delivery. Significant enhancement of isoproterenol-stimulated in vivo cardiac function after Adeno-β2AR treatment was also seen 21 days after gene delivery when compared with EV-treated rabbits, even though β2-AR overexpression was drastically reduced compared with overexpression seen at 1 week. This minimal overexpression at 3 weeks was statistically significant compared with endogenous β-AR density, and although this level of overexpression no longer resulted in enhanced basal LV +dP/dtmax compared with EV-treated rabbits, β-AR responsiveness was still significantly elevated. Thus, prolonged β2-AR overexpression appears to be responsible for maintained elevated in vivo contractile responses at 3 weeks.

Interestingly, there appears to be a “therapeutic window” of β2-AR overexpression, as levels >800 fmol/mg membrane protein, produced by increasing the viral dose, resulted in a decline of in vivo function (data not shown). This could be due to viral toxicity and immunological responses of the host animal at these higher doses. Attenuated function was seen when higher (>1012 tvp) doses of EV were also administered (data not shown), indicating that it is a general feature of adenovirus delivery and not specifically due to higher levels of β2-AR overexpression.

Our study demonstrates that global myocardial expression is possible in vivo through intracoronary adenovirus delivery. Previous ex vivo models in the heart have demonstrated that intracoronary infusions of adenovirus can lead to global transgene expression (18, 24, 25). We have used a heterotopic rat heart transplant model to deliver Adeno-β2AR to the transplanted rat heart, and this has led to both basal and β-agonist–mediated increases in cardiac contractility measured in the isolated heart by Langendorff perfusion (25). Thus, β2-AR overexpression in both the transplanted rat heart and the rabbit heart in vivo can enhance global myocardial function.

These adenoviral-mediated gene transfer experiments were done to determine whether the hearts of larger animals could be manipulated similarly to those of transgenic mice. Previous work by our laboratory demonstrated that myocardial-targeted overexpression of the human β2-AR transgene in transgenic mice at extraordinary levels (>200-fold over endogenous levels) led to dramatic increases in cardiac function (8). It is obvious that we will not approach this level of overexpression of β2-ARs using adenoviruses; however, Liggett and colleagues have generated additional transgenic mice overexpressing β2-ARs in the heart at levels in the range of the overexpression seen in our adenoviral-treated rabbit hearts, and cardiac in vivo contractility was still enhanced (9). Thus, our results in the rabbit demonstrate that ∼10-fold overexpression of myocardial β2-ARs can lead to enhanced contractility in vivo.

These studies demonstrate that β2-AR overexpression in the context of normal myocardium can lead to increases in cardiac contractility; however, potential clinical use would be in a heart in which function is compromised. Multiple lines of evidence, including experiments presented in this study, suggest that β2-AR overexpression in the failing heart might be of clinical utility. We have shown that Adeno-β2AR treatment of cardiac myocytes isolated and cultured from post–myocardial infarction rabbits that are in congestive HF can restore dysfunctional β-AR signaling, as measured by intracellular cAMP accumulation (Figure 7). Thus, alterations in the β-AR system in the failing heart can be restored after acute adenoviral-mediated gene transfer, demonstrating the feasibility of genetically replacing lost β-ARs in the failing heart.

In addition, hybrid transgenic mouse studies have shown that modest (30-fold) myocardial overexpression of β2-ARs can rescue signaling, hypertrophy, and baseline ventricular function in a Gαq overexpression model of hypertrophic dysfunction (26). More importantly, data supporting the potential clinical significance of β2-AR gene therapy for HF include the recent findings that HF patients possessing a β2-AR gene polymorphism resulting in a β2-AR that couples to adenylyl cyclase less efficiently have significantly lower survival rates (27). Thus, gene therapy using the wild-type β2-AR, which couples efficiently to adenylyl cyclase, may be potentially useful in human HF especially in this population of patients. Furthermore, 2 recent studies of patients with severe HF have demonstrated that there is contractile reserve in failing myocardium. It has been shown that failing myocardium retains a certain capacity to recover functionally; it also undergoes “reverse remodeling” and regression of hypertrophy after use of a LV mechanical assistance device (28, 29). These data suggest that it might be possible to treat failing myocardium by replacing lost receptors and that failing myocytes will support enhanced adrenergic signaling through β2-ARs.

Efficient gene transfer in vivo to the rabbit heart, as described here, now makes it possible to study potential molecular therapies, as there are reliable in vivo HF models available. It has yet to be determined whether our method of in vivo transgene delivery will rescue the failing rabbit heart, but this will be a focus of future studies. Nevertheless, our current results demonstrate the feasibility of acute in vivo global myocardial transgenesis in investigating important molecular targets for the treatment of cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank K. Shotwell, K. Campbell, and A. Pippen for technical assistance, and A. Kypson and R.E. Lilly for critical contributions throughout these studies. We also thank the Genzyme Corporation (Framingham, Massachusetts, USA) for preparation and purification of Adeno-β2AR. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HL-16037 (to R.J. Lefkowitz), HL-59533 (to W.J. Koch), and HL-56205 (to W.J. Koch), and a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association (to W.J. Koch).

Footnotes

John P. Maurice and Jonathan A. Hata contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Cohn JN, et al. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Special Emphasis Panel on Heart Failure Research. Circulation. 1997;95:766–770. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodde OE. Beta-adrenoceptors in cardiac disease. Pharmacol Ther. 1993;60:405–430. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90030-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bristow MR, et al. Decreased catecholamine sensitivity and β-adrenergic receptor density in failing human hearts. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ping P, Anzai T, Gao M, Hammond HK. Adenylyl cyclase and G protein receptor kinase expression during development of heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H707–H717. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.2.H707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bristow MR, et al. Reduced β1 receptor messenger RNA abundance in the failing human heart. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2737–2745. doi: 10.1172/JCI116891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ungerer M, Bohm M, Elce JS, Erdmann E, Lohse ML. Altered expression of β-adrenergic receptor kinase and β1-adrenergic receptors in the failing heart. Circulation. 1993;87:454–463. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bristow MR, Lowes BD. Low-dose inotropic therapy for ambulatory heart failure. Coron Artery Dis. 1994;5:112–118. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199402000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milano CA, et al. Enhanced myocardial function in transgenic mice overexpressing the β2-adrenergic receptor. Science. 1994;264:582–586. doi: 10.1126/science.8160017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turki J, et al. Myocardial signaling defects and impaired cardiac function of a human β2-adrenergic receptor polymorphism expressed in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10483–10488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhter SA, et al. Restoration of β-adrenergic signaling in failing cardiac ventricular myocytes via adenoviral-mediated gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12100–12105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kass-Eisler A, et al. Quantitative determination of adenovirus-mediated gene delivery to rat cardiac myocytes in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11498–11502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French BA, Mazur W, Geske RS, Bolli R. Direct in vivo gene transfer into porcine myocardium using replication-deficient adenoviral vectors. Circulation. 1994;90:2414–2424. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magovern CJ, et al. Direct in vivo gene transfer to canine myocardium using a replication-deficient adenovirus vector. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:425–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr E, et al. Efficient catheter-mediated gene transfer into the heart using replication-defective adenovirus. Gene Ther. 1994;1:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giordano FJ, et al. Intracoronary gene transfer of fibroblast growth factor-5 increases blood flow and contractile function in an ischemic region of the heart. Nat Med. 1996;2:534–539. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajjar RJ, et al. Modulation of ventricular function through gene transfer in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5251–5256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drazner MH, et al. Potentiation of β-adrenergic signaling by adenoviral-mediated gene transfer in adult rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:288–296. doi: 10.1172/JCI119157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kypson AP, et al. Ex vivo adenoviral-mediated gene transfer to the transplanted adult rat heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:623–630. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch WJ, et al. Cardiac function in mice overexpressing the β-adrenergic receptor kinase or a βARK inhibitor. Science. 1995;268:1350–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.7761854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silvestry SC, et al. The in vivo quantification of myocardial performance in rabbits: a model for evaluation of cardiac gene therapy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:815–823. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maurice JP, et al. Molecular β-adrenergic signaling abnormalities in failing rabbit hearts after infarction. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1853–1860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelhardt JF, Ye X, Doranz B, Wilson JM. Ablation of E2A in recombinant adenoviruses improves transgene persistence and decreases inflammatory response in mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6196–6200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Jooss KU, Su Q, Ertl HCJ, Wilson JM. Immune responses to viral antigens versus transgene product in the elimination of recombinant adenovirus-infected hepatocytes in vivo. Gene Ther. 1996;3:137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donahue JK, Kikkawa K, Johns DC, Marban E, Lawrence JH. Ultrarapid, highly efficient viral gene transfer to the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4664–4668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kypson, A.P., et al. 1999. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of the β2-adrenergic receptor to donor hearts enhances cardiac function. Gene Ther. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Dorn GW, et al. Low- and high-transgenic expression of β2-adrenergic receptors differentially affects cardiac hypertrophy and function in Gαq overexpressing mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6400–6405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liggett SB, et al. The ile164 β2-adrenergic receptor polymorphism adversely affects the outcome of congestive heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1534–1539. doi: 10.1172/JCI4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dipla K, Mattiello JA, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Myocyte recovery after mechanical circulatory support in humans with end-stage heart failure. Circulation. 1998;97:2316–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.23.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zafeiridis A, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Regression of cellular hypertrophy after left ventricular assist device support. Circulation. 1998;98:656–662. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]