Abstract

Galα1,3Gal–reactive (Gal-reactive) antibodies are a major impediment to pig-to-human xenotransplantation. We investigated the potential to induce tolerance of anti-Gal–producing cells and prevent rejection of vascularized grafts in the combination of α1,3-galactosyltransferase wild-type (GalT+/+) and deficient (GalT–/–) mice. Allogeneic (H-2 mismatched) GalT+/+ bone marrow transplantation (BMT) to GalT–/– mice conditioned with a nonmyeloablative regimen, consisting of depleting CD4 and CD8 mAb’s and 3 Gy whole-body irradiation and 7 Gy thymic irradiation, led to lasting multilineage H-2bxd GalT+/+ + H-2d GalT–/– mixed chimerism. Induction of mixed chimerism was associated with a rapid reduction of serum anti-Gal naturally occurring antibody levels. Anti-Gal–producing cells were undetectable by 2 weeks after BMT, suggesting that anti-Gal–producing cells preexisting at the time of BMT are rapidly tolerized. Even after immunization with Gal-bearing xenogeneic cells, mixed chimeras were devoid of anti-Gal–producing cells and permanently accepted donor-type GalT+/+ heart grafts (>150 days), whereas non-BMT control animals rejected these hearts within 1–7 days. B cells bearing receptors for Gal were completely absent from the spleens of mixed chimeras, suggesting that clonal deletion and/or receptor editing may maintain B-cell tolerance to Gal. These findings demonstrate the principle that induction of mixed hematopoietic chimerism with a potentially relevant nonmyeloablative regimen can simultaneously lead to tolerance among both T cells and Gal-reactive B cells, thus preventing vascularized xenograft rejection.

Introduction

Xenotransplantation of pig organs into humans is a possible solution to the shortage of donor organs for transplantation (1, 2), but hyperacute rejection (HAR) is a major obstacle to its success. In pig-to-primate species combinations, HAR is initiated by the binding of naturally occurring antibodies against the carbohydrate Galα1,3Gal (Gal) epitope on vascular endothelium of the xenografts (3–5). Although a variety of strategies to prevent anti-Gal–mediated rejection have been proposed (6–11), none has proved entirely successful. Although HAR is avoided with these approaches, acute vascular rejection or delayed xenograft rejection (DXR), which appears to be mediated in part by anti-Gal antibodies and may be complement independent, inevitably occurs (12–14).

Thus, it is likely that complete, or almost complete, elimination of Gal epitopes from the xenografts, or specific suppression of anti-Gal production, will be required to prevent anti-Gal–mediated rejection of porcine xenografts in humans (12, 13, 15). Induction of B-cell tolerance to specific xenoantigens would permanently avoid the problem of antibody-mediated rejection. Xenoreactive B-cell tolerance has been induced in T cell–deficient or cyclosporine-treated rats receiving hamster heart grafts under cover of a 4-week course of Leflunomide (Hoescht Pharmaceuticals, Weisbaden, Germany) (16, 17). Although this strategy effectively avoids antibody-mediated rejection of xenografts, the applicability to Gal-reactive antibodies remains to be determined, and long-term T-cell immunosuppression is required to prevent cellular rejection. A recent report suggests that Gal-reactive B-cell tolerance cannot be achieved without lifelong chimerism, as tolerance to Gal was not induced by neonatal antigenic exposure, which can induce T-cell tolerance (18). We have recently proposed the possibility of tolerizing anti-Gal naturally occurring antibody–producing (NAb-producing) B cells in xenograft recipients by the induction of mixed chimerism, which would simultaneously induce T-cell tolerance. Using α1,3-galactosyltransferase–deficient (GalT–/–) mice, which resemble humans in that their sera contain anti-Gal NAb’s, as recipients, and wild-type (GalT+/+) mice as donors, we have demonstrated that GalT+/+ plus GalT–/– bone marrow transplantation (BMT) into lethally irradiated GalT–/– mice can induce a state of mixed chimerism that is associated with specific tolerance of anti-Gal NAb–producing B cells (19). However, lethal irradiation is not a conditioning treatment that would be considered reasonable for use in humans needing organ transplantation. We now demonstrate that mixed chimerism, with vascularized GalT+/+ donor heart graft acceptance, can be induced in GalT–/– mice using a more clinically relevant, less toxic, nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, which does not include specific treatments to remove preexisting host anti-Gal–producing cells. Anti-Gal–producing cells were undetectable by 2 weeks after BMT, suggesting that anti-Gal–producing cells preexisting in the GalT–/– recipients at the time of BMT are rapidly tolerized by the induction of mixed chimerism. In addition, we provide data suggesting that a state of B-cell tolerance to Gal may be maintained by clonal deletion and/or receptor editing in mixed chimeras.

Methods

Animals.

GalT–/– (H-2d) mice and GalT+/+ (H-2bxd and H-2d) mice were derived from hybrid (129SV × DBA/2 × C57BL/6) animals (20). All mice used in this study were confirmed by flow cytometric (FCM) analysis to express homozygous levels of the Ly-2.2 allele. C.B.-17 scid/scid (C.B.-17 scid) mice were purchased from the Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts, USA). All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen–free microisolator environment.

Conditioning and BMT.

Age-matched (8- to 12-week-old) GalT–/– (H-2d) recipient mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1.8 mg and 1.4 mg of rat IgG2b anti-mouse CD4 mAb GK1.5 (21) and anti-mouse CD8 mAb 2.43 (anti–Ly-2.2 mAb) (22), respectively, on day –5 of BMT. On day 0, 3 Gy whole-body irradiation and 7 Gy selective thymic irradiation were given to mAb-treated animals, as described (23). Bone marrow cells (BMCs) from GalT+/+ (H-2bxd) donors were depleted of T cells, using anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 mAb’s and rabbit complement as described, and were administered intravenously on day 0 (24).

FCM analysis of chimerism.

Chimerism was evaluated by 2-color FCM analysis of peripheral white blood cells (WBCs) on a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, California, USA) as described (25). Cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 (PharMingen, San Diego, California, USA), anti-CD8 (Caltag Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, California, USA; and PharMingen), B220 (PharMingen), and anti-MAC1 (Caltag Laboratories Inc.) mAb’s, together with biotinylated anti–donor mouse H-2Kb mAb 5F1 (26). The biotinylated mAb was viewed with phycoerythrin-streptavidin (PE-streptavidin). Forward angle and 90° light scatter properties were used to distinguish lymphocytes, granulocytes, and monocytes in WBCs. The percentage of donor cells (staining with 5F1) was calculated separately for each cell population.

FCM analysis of anti-Gal and anti-rabbit red blood cell antibodies.

Indirect immunofluorescence stainings of C.B.-17 scid mouse spleen cells and BMCs (which express the Gal epitope and lack surface Ig+ B cells) or rabbit erythrocytes were used to detect anti-Gal NAb’s and anti-rabbit erythrocyte antibodies, respectively. One million cells were incubated with 10 μL of serially diluted mouse serum, washed, and then incubated with FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgM mAb (PharMingen). The specificity for anti-Gal NAb in sera of GalT–/– mice, as detected by staining of scid mouse cells in this assay, has been verified by anti-Gal NAb–specific ELISA assay, which revealed a strong correlation between data obtained by these 2 methods (r > 0.90) (19).

ELISA assays.

Anti-Gal levels in sera were quantified by ELISA according to procedures described previously (19). Total immunoglobulin levels in sera were also quantified by ELISA. ELISA plates were coated with 5 μg/mL of goat anti-mouse IgG or IgM (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, Alabama, USA). Diluted serum samples were incubated in the plates, and bound antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (250 ng/mL; Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc.). Color development was achieved using 0.1 mg/mL o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) in substrate buffer. The OPD reaction was stopped using 3 M NH2SO4, and absorbance at 492 nm was measured.

Enzyme-linked immunospot for detecting anti-Gal–producing cells.

The enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay was performed as described previously (19). Briefly, nitrocellulose membranes from a 96-well filtration plate (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Massachusetts, USA) were coated with 5 μg/mL of synthetic Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAc conjugated to BSA (Gal-BSA; Alberta Research Council, Alberta, Alberta, Canada). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 0.4% BSA in culture medium. Serial dilutions of spleen, bone marrow, or peritoneal cell suspension were added to triplicate wells. After a 24-hour culture at 37°C, bound anti bodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM plus IgG antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc.), followed by color development with 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (Sigma Chemical Co.).

FCM analysis and cell sorting of B cells bearing receptors for Gal.

One million cells per 100 μL were incubated with 0.5 μg/100 μL FITC-conjugated Gal-BSA (Alberta Research Council) or 0.5 μg/100 μL control FITC-conjugated BSA (Fisher Scientific Co., Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA) in FCM medium for 2 hours at 4°C, together with biotinylated anti-mouse IgM mAb (PharMingen) (for 2-color FCM) or PE-conjugated anti-CD19 (PharMingen) and biotinylated anti–donor mouse H-2Kb 5F1 mAb’s (for 3-color FCM). FITC conjugation of Gal-BSA and BSA was performed with the QuickTag FITC Conjugation Kit (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Biotinylated mAb’s were viewed with PE-streptavidin (for 2-color FCM) or CyChrome-streptavidin (for 3-color FCM). Based on Gal-BSA binding and IgM expression, splenic Gal-BSA+/IgM+ and Gal-BSA–/IgM+ populations were sorted under sterile conditions using a MoFlo high-speed cell sorter (Cytomation, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA). Sorted cells were immediately resuspended in culture medium and applied to ELISPOT plates precoated with Gal-BSA to determine the frequency of anti-Gal (IgM)–producing cells.

Heterotopic heart transplantation.

Cervical heterotopic heart transplantation was performed using the cuff technique modified from a method described previously (27). Briefly, the recipients were initially prepared before the donor heart harvest to minimize the graft ischemic time. The right external jugular vein and the right common carotid artery were dissected free, mobilized as far as possible, and fixed to the appropriate cuffs. The cuffs were composed of polyethylene tubes (2.5F; Portex Ltd., London, United Kingdom) in which diameters were adjusted by the physical extension. The aorta and the main pulmonary artery of the harvested donor heart were drawn over the end of the common carotid artery and the external jugular vein for the anastomoses. The ischemic time of the graft hearts was less than 30 minutes. The function of the grafts was monitored by daily inspection and palpation. Rejection was determined by the cessation of beating of the graft and was confirmed by histology.

Histological studies.

Formalin-fixed grafted heart tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined microscopically. Fresh frozen grafted heart tissue sections were stained with fluorescein-labeled anti-mouse IgG and IgM (Sigma Chemical Co.) and C3 (Cappel Research Products, Durham, North Carolina, USA) and were examined by fluorescence microscopy.

Statistics.

The results were statistically analyzed by the unpaired or paired Student’s t test of means or the log rank test when appropriate. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Lasting multilineage GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimerism can be induced by nonmyeloablative conditioning.

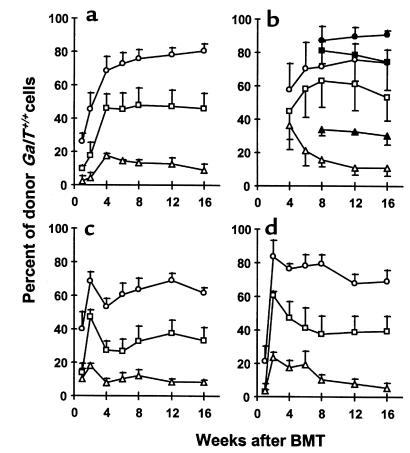

To determine whether GalT+/+ pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell engraftment could be achieved in GalT–/– recipients treated with a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen that permits the development of allogeneic chimerism and T-cell tolerance across MHC barriers (23), we administered varying doses (20 × 106, 7.5 × 106, and 1 × 106) of T cell–depleted GalT+/+ BMCs (H2bxd) to GalT–/– recipients (H-2d) conditioned with depleting anti-CD4 plus anti-CD8 mAb’s on day –5, and with 3 Gy whole-body irradiation and 7 Gy thymic irradiation on day 0. In addition to the Gal epitope, the donor strain expressed a full MHC haplotype (H-2b) not shared by the recipients. Untreated GalT–/– and GalT+/+ mice, and conditioned GalT–/– and GalT+/+ mice not receiving BMT, served as controls. In all recipients of 20 × 106 and 7.5 × 106 BMCs (n = 5 per group), and in 3 of 5 recipients of 1 × 106 BMCs, lasting mixed chimerism was observed in peripheral blood B cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, monocytes, and granulocytes at all times (Figure 1). Erythrocyte chimerism could not be detected because of low levels of Gal and H-2 expression on erythrocytes. Our data indicate that lasting multilineage GalT+/+→GalT–/– chimerism could be induced with nonmyeloablative conditioning when appropriate doses of BMCs are transplanted.

Figure 1.

Long-lasting multilineage GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimerism in recipients prepared with a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen. Peripheral WBCs were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4, anti-CD8, B220, and anti-MAC1 mAb’s, together with biotinylated anti–donor mouse H-2Kb 5F1 mAb and PE-streptavidin. Cells staining with 5F1 were identified as donor-derived cells. Kinetics of donor reconstitution (mean ± SEM) among B cells (a), T cells (b; open symbols: CD4+ cells; closed symbols: CD8+ cells), monocytes (c), and granulocytes (d) in WBCs. GalT–/– (H-2d) mice received anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 mAb’s on day –5, followed by whole-body irradiation (3 Gy), thymic irradiation (7 Gy), and T cell–depleted GalT+/+ (H-2bxd) BMCs (circles: 20 × 106 BMCs [n = 5]; squares: 7.5 × 106 BMCs [n = 5]; triangles: 1 × 106 BMCs [n = 3]) on day 0.

Loss of anti-Gal NAb’s in mixed GalT+/+→GalT–/– chimeras.

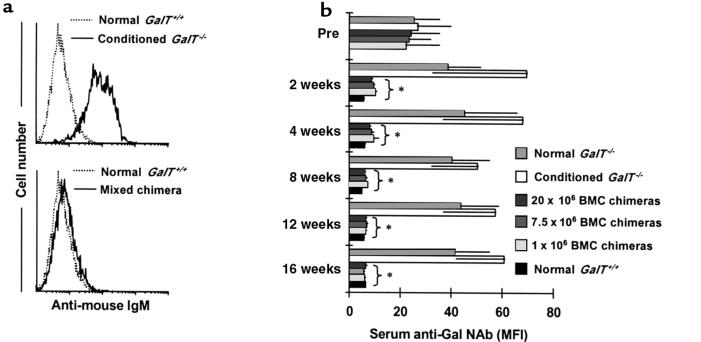

The kinetics of serum anti-Gal NAb levels in each group are shown in Figure 2. In the control untreated GalT–/– mice, serum anti-Gal NAb levels showed a gradual increase during the observation period, consistent with the age-related increase in mouse NAb described previously (28). In the control non-BMT GalT–/– mice that received conditioning treatment, serum anti-Gal NAb levels increased further at 2 weeks (P < 0.05 before conditioning vs. 2 weeks after conditioning) and remained high throughout the follow-up period. This increase of anti-Gal NAb levels may be due to loss of regulation by T cells, as similar results were observed in GalT–/– mice treated only with depleting anti-CD4 plus anti-CD8 mAb’s (H. Ohdan et al., manuscript in preparation). In contrast, GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimeras had significantly reduced serum levels of anti-Gal NAb by 2 weeks after BMT. These declined further over time, eventually becoming undetectable above the level observed in control GalT+/+ mice.

Figure 2.

Reduced anti-Gal NAb levels in sera of GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimeras. (a) Representative histograms obtained by FCM analysis show an absence of anti-Gal NAb’s in GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimeras. C.B.-17 scid mouse (GalT+/+) spleen and BMCs were stained with sera from normal GalT+/+, from control conditioned GalT–/– mice, or from BMT recipients; NAb’s were detected using rat anti-mouse IgM-FITC as secondary mAb. Representative histogram appearances from sera obtained at 4 weeks after conditioning/BMT are shown (10 μL of undiluted serum per 1 × 106 C.B.-17 scid cells was used). (b) Kinetics of serum anti-Gal NAb levels measured by FCM analysis. The anti-Gal NAb levels are presented as median fluorescence intensity (MFI). Average values ± SEM for the individual groups are shown. Number of animals in each group: normal GalT–/– mice, n = 6; conditioned GalT–/– mice, n = 5; chimeras receiving 20 × 106 BMCs, n = 5; chimeras receiving 7.5 × 106 BMCs, n = 5; chimeras receiving 1 × 106 BMCs, n = 3; and normal GalT+/+ mice, n = 5. *P < 0.05 compared with similarly conditioned GalT–/– control mice that did not receive BMT. There was no statistical difference between BMT chimeras and normal GalT+/+ control mice after 4 weeks.

Absence of anti-Gal–producing cells in mixed chimeras.

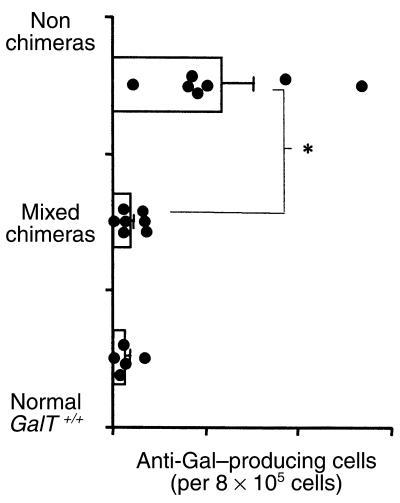

The observation that mixed GalT+/+→GalT–/– chimerism led to a specific reduction in anti-Gal NAb’s suggested that GalT+/+ hematopoietic chimerism led to tolerance of anti-Gal NAb–producing cells. However, to rule out the possibility that anti-Gal NAb’s were merely absorbed by the Gal epitope expressed on engrafted GalT+/+ cells, the presence of anti-Gal–producing cells was assessed by ELISPOT assay. Eighteen to 19 weeks after BMT, chimeras were immunized by intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 rabbit erythrocytes, which express large amounts of Gal (29). Eight days after immunization, anti-Gal (IgM and IgG)–producing cells were quantified in recipient spleen cells, BMCs, and peritoneal cavity cells. As is shown in Figure 3a, cells producing anti-Gal were undetectable in all 3 tissues of mixed chimeras, whereas large numbers of these cells were detected predominantly in the spleen of both untreated and conditioned GalT–/– mice. The results in mixed chimeras resembled those from control GalT+/+ mice, which also lacked cells producing anti-Gal. In artificial mixtures of spleen cells from GalT+/+ and GalT–/– mice immunized with rabbit erythrocytes, a linear relationship between the frequency of anti-Gal–producing cells and the percentages of GalT–/– cells in the mixtures (r2 = 0.9881) was observed (data not shown), ruling out absorption of anti-Gal by GalT+/+ cells of mixed chimeras in the ELISPOT assay.

Figure 3.

Absence of anti-Gal–producing cells in GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimeras (19–20 weeks after BMT). (a) ELISPOT detection of anti-Gal–producing (IgM + IgG) cells. Spleen cells (SPL), BMCs (BM), and peritoneal cavity cells (Per C), prepared from normal and conditioned GalT–/– mice, normal GalT+/+ mice, and mixed chimeras 8 days after immunization with rabbit erythrocytes, were used in ELISPOT assay. The frequency of anti-Gal–producing cells was determined as average of red plaque number in triplicate wells of serially diluted cells. The results shown are the average values ± SEM for the individual groups. Number of animals in each group: normal GalT–/– mice, n = 4; normal GalT+/+ mice, n = 4; conditioned GalT–/– mice, n = 5; GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimeras, n = 7 (results are combined for recipients of 20 × 106, 7.5 × 106, and 1 × 106 BMCs). *P < 0.05 compared with normal control GalT–/– mice and similarly conditioned GalT–/– control mice that did not receive BMT. There was no statistically significant difference between mixed chimeras and normal GalT+/+ control mice in any tissue. (b) Serum levels of anti-Gal antibodies after immunization with Gal-bearing xenogeneic cells. Normal and conditioned GalT–/– mice, normal GalT+/+ mice, and mixed chimeras were immunized with rabbit erythrocytes, and serum anti-Gal levels were measured by ELISA assay 8 days after immunization. Average values ± SEM for the individual groups are shown. Number of animals in each group: normal GalT–/– mice, n = 5; conditioned GalT–/– mice, n = 4; mixed chimeras, n = 13 (results are combined for recipients of 20 × 106, 7.5 × 106, and 1 × 106 BMCs); normal GalT+/+ mice, n = 5. *P < 0.05 compared with normal control GalT–/– mice and similarly conditioned GalT–/– control mice that did not receive BMT. There was no statistical difference between mixed chimeras and normal GalT+/+ control mice at any serum dilution in either anti-Gal IgM or IgG levels.

Consistent with the absence of anti-Gal–producing cells in mixed chimeras, serum levels of anti-Gal (both IgM and IgG) in mixed chimeras were undetectable, even after immunization with rabbit erythrocytes (Figure 3b). In mixed chimeras and conditioned GalT–/– mice, total serum IgM and IgG levels were maintained at normal levels at all time points (data not shown). In all mixed chimeras, serum levels of anti-rabbit erythrocyte IgM antibody were elevated after immunization with rabbit erythrocytes, to levels similar to those detected in normal GalT+/+ control mice (data not shown). Thus, the absence of a response to Gal, and the preserved normal response to other rabbit erythrocyte antigens in mixed GalT+/+→GalT–/– chimeras, confirms the presence of specific tolerance of Gal-reactive B cells.

Tolerance was apparent as early as 2 weeks after BMT, as indicated by the experiment presented in Figure 4, in which conditioned GalT–/– mice received 20 × 106 GalT+/+ BMCs that were either untreated or irradiated with 30 Gy. The use of irradiated GalT+/+ BMT provided an appropriate control in which mixed chimerism could not be induced, but similar antigenic exposure occurred. As expected, mixed chimerism was observed in all recipients of nonirradiated BMCs, but not in the recipients of irradiated BMCs. Despite the presence of host B cells in mixed chimeras at 2 weeks (mean: 42.7 ± 4.7% of splenic CD19+ cells), cells producing anti-Gal (IgM or IgG) were undetectable in the spleens of mixed chimeras by ELISPOT assay. In contrast, most conditioned GalT–/– recipients of irradiated GalT+/+ BMCs had measurable anti-Gal–producing spleen cells. The frequency of anti-Gal–producing cells in the control conditioned GalT–/– mice receiving irradiated GalT+/+ BMCs was similar to that of untreated normal GalT–/– mice (data not shown). Thus, mixed hematopoietic chimerism is necessary for the induction of B-cell tolerance, as opposed to antigen exposure alone. Anti-Gal–producing cells were tolerant in mixed chimeras by 2 weeks after BMT.

Figure 4.

Absence of anti-Gal–producing cells in mixed chimeras 2 weeks after BMT (ELISPOT detection of anti-Gal IgM/IgG–producing cells). Spleen cells from conditioned GalT–/– mice receiving 20 × 106 GalT+/+ BMCs (mixed chimeras), from conditioned GalT–/– mice receiving 20 × 106 30 Gy–irradiated GalT+/+ BMCs (nonchimeras), and from normal GalT+/+ mice were used in ELISPOT assay. The frequency of anti-Gal–producing cells was determined as the average of red plaque numbers in triplicate wells of 8 × 105 cells. Average values ± SEM for the individual groups are shown. Each point represents an individual mouse. *P < 0.05 compared with conditioned GalT–/– mice receiving irradiated BMCs.

Absence of B cells bearing receptors for Gal in the spleens of mixed chimeras.

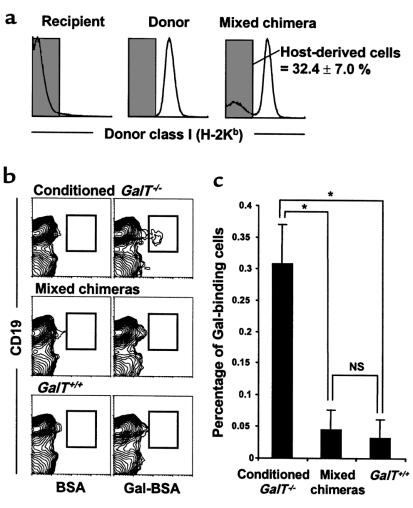

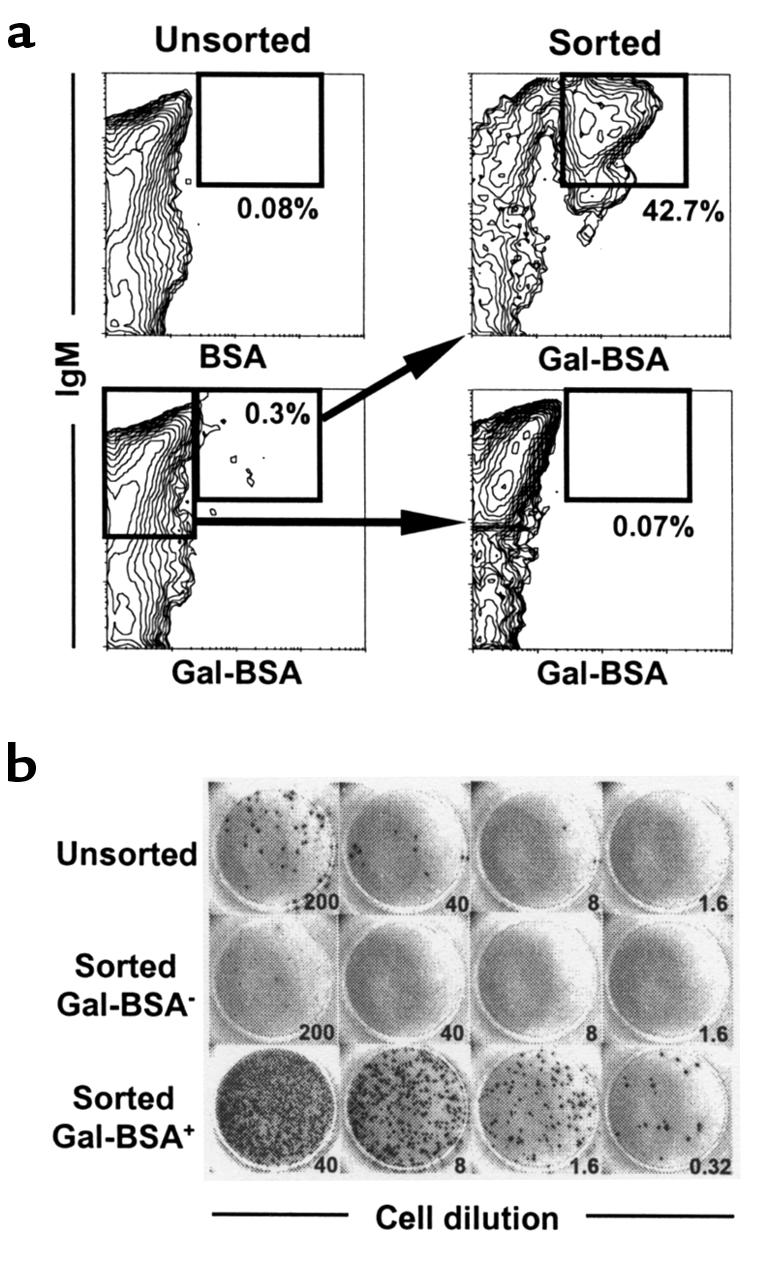

By surface staining with FITC-conjugated Gal-BSA, B cells bearing surface IgM (sIgM) receptors that can recognize Gal epitopes could be identified. In normal GalT–/– mice immunized intraperitoneally with 1 × 109 rabbit erythrocytes, Gal-BSA–binding B cells were detected in the spleen (a primary site of anti-Gal production, as demonstrated in Figure 3a) (Figure 5a). The combined FCM sorting and ELISPOT assay revealed that anti-Gal (IgM)–producing cells were greatly enriched in the sorted Gal-BSA+/IgM+ population, but were undetectable in the sorted Gal-BSA–/IgM+ population (Figure 5b), demonstrating that the Gal-BSA–binding spleen cells included all anti-Gal–producing cells.

Figure 5.

B cells bearing receptors for Gal detected by Gal-BSA comprise the anti-Gal–producing population in the spleens of GalT–/– mice. Spleen cells were prepared from 5 normal GalT–/– mice (12 weeks of age) 8 days after immunization by intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 rabbit erythrocytes. The pooled cells were stained with FITC-conjugated Gal-BSA or control FITC-conjugated BSA, together with biotinylated anti-mouse IgM mAb and PE-streptavidin. The populations of Gal-BSA–binding and –nonbinding B cells (IgM+) were sorted as described in Methods. (a) FCM results of Gal-BSA–binding spleen cells. Sorted cells were reanalyzed for purity; 30,000 cells were analyzed for each contour plot. Percentages given are of total spleen cells. (b) ELISPOT detection of anti-Gal (IgM)–producing cells. The frequencies of anti-Gal–producing cells were determined for unsorted and sorted cells by ELISPOT assay. Numbers refer to the total cells seeded per well (×103). Anti-Gal–producing cells were greatly enriched in the sorted Gal-BSA–binding B-cell population. The calculated frequencies of anti-Gal–producing cells were 0.1/103, 0.005/103, and 56/103 in the unsorted, sorted Gal-BSA–/IgM+, and Gal-BSA+/IgM+ populations, respectively.

To address the question of how the specific tolerance of Gal-reactive B cells was maintained in mixed chimeras, we looked for the presence of B cells bearing receptors for Gal in long-term mixed chimeras. Spleen cells from mixed chimeras were analyzed for Gal-BSA–binding B cells 22 weeks after BMT and 8 days after immunization by intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 rabbit erythrocytes. Gal-BSA–binding spleen cells were detected in control conditioned GalT–/– mice that did not receive BMT; they were undetectable in GalT+/+ mice (Figure 6b). In mixed chimeras, the frequency of Gal-BSA–binding splenic B cells among host-derived cells (GalT–/–) was markedly lower than in conditioned GalT–/– mice, and resembled that of GalT+/+ mice (Figure 6c). Thus, B cells bearing receptors for Gal were absent from the major site of anti-Gal production in mixed chimeras.

Figure 6.

Absence of B cells bearing receptors for Gal in the spleens of mixed chimeras (22 weeks after BMT). Spleen cells were prepared from conditioned GalT–/– mice (H-2d), normal GalT+/+ mice (H-2d), and mixed chimeras (H-2bxd→H-2d) 8 days after immunization with rabbit erythrocytes. The cells were stained with FITC-conjugated Gal-BSA or control FITC-conjugated BSA together with PE-conjugated anti-CD19 mAb and biotinylated anti–donor mouse H-2Kb 5F1 mAb + CyChrome-streptavidin. (a) In mixed chimeras, the host-derived H-2Kb–negative cells were selected by gating and analyzed for the frequency of Gal-BSA–binding B cells. The percentage of host-derived cells in the spleens of mixed chimeras is indicated as average value ± SEM. (b) Representative contour plots obtained by FCM analysis show an absence of Gal-BSA–binding B cells in the spleens of mixed chimeras. To ensure statistical significance, data on 100,000 host-derived cells were collected for each sample. (c) The frequency of Gal-BSA–binding B cells was calculated by subtracting the percentage of CD19+ cells staining with control FITC-conjugated BSA from the percentage of CD19+ cells staining with FITC-conjugated Gal-BSA. Percentages of total host-derived spleen cells are shown. Average values ± SEM for the individual groups are shown (*P < 0.01; NS = no statistical difference). Number of animals in each group: conditioned GalT–/– mice that did not receive BMT, n = 4; mixed chimeras, n = 4; normal GalT+/+ mice, n = 4.

Permanent acceptance of hearts from GalT+/+ mice in mixed chimeras.

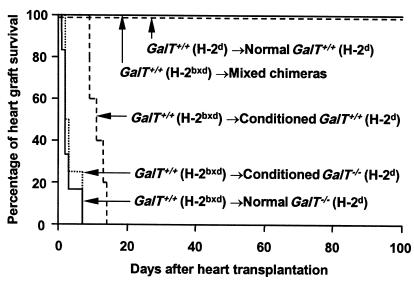

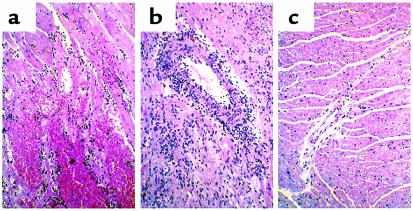

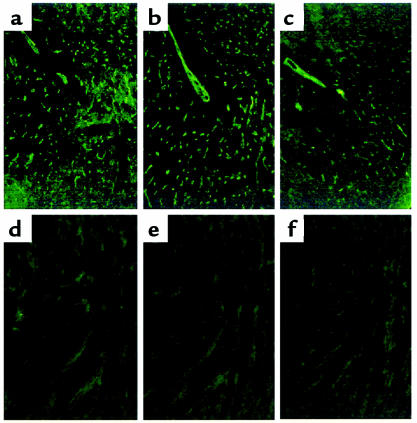

To evaluate T-cell and antibody tolerance in mixed GalT+/+ (H-2bxd)→GalT–/– (H-2d) chimeras, we transplanted hearts from donor-type GalT+/+ (H-2bxd) mice to chimeras 19–20 weeks after BMT. To enhance anti-Gal production, recipient animals were immunized by intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 rabbit erythrocytes 8 or 9 days before heart transplantation. All untreated and conditioned control H-2d GalT–/– mice (n = 6 and n = 4, respectively) rejected H-2bxd GalT+/+ hearts within 1–7 days (Figure 7). Upon histological and immunohistological examination, hearts rejected at early time points (1–3 days; 8 of 10 animals) showed massive interstitial hemorrhage, neutrophil infiltration (Figure 8a), and deposition of IgM, IgG, and the C3 component of complement on the capillary and vessel endothelia (Figure 9, a–c). These are all major features of humoral rejection. In contrast, the hearts rejected at later time points in this group (7 days; 2 animals) showed diffuse mononuclear cell infiltration, in addition to IgM, IgG, and C3 deposition. All conditioned control H-2d GalT+/+ mice (n = 5) rejected H-2bxd GalT+/+ hearts in 9–14 days (Figure 7). These rejected hearts showed severe diffuse mononuclear cell infiltration and myocardial necrosis (Figure 8b), which were typical features of cell-mediated rejection, but significant deposits of IgM, IgG, and C3 were not observed. In contrast, in all mixed chimeras (n = 5) — except for one that died in 6 days with a nonrejecting, histologically normal-looking heart — grafted GalT+/+ hearts survived indefinitely (>150 days) (Figure 7). None of these surviving hearts revealed any histological sign of rejection, and they showed a complete absence of immunoglobulin and complement deposition at day 165 (Figure 8c and Figure 9, d–f).

Figure 7.

Permanent acceptance of GalT+/+ donor-type hearts in GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimeras. The hearts from donor-type GalT+/+ (H-2bxd) mice were heterotopically transplanted into mixed chimeras (n = 6; including 2 chimeras transplanted with 20 × 106, 7.5 × 106, or 1 × 106 GalT+/+ BMCs) 19–20 weeks after BMT, as well as into conditioned control GalT–/– (H-2d) (n = 6) and GalT+/+ mice (H-2d) (n = 5) and untreated control GalT–/– mice (H-2d) (n = 4). As an H-2–identical control, hearts from GalT+/+ (H-2d) mice were transplanted into GalT+/+ (H-2d) mice (n = 3). To enhance anti-Gal NAb production, all recipient animals were immunized by intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 rabbit erythrocytes 8 or 9 days before heart transplantation. Survival curves of the grafted hearts are shown. P < 0.005 normal GalT–/–, conditioned GalT–/–, or conditioned GalT+/+ vs. mixed chimeras. P < 0.005 normal GalT–/– or conditioned GalT–/– vs. conditioned GalT+/+.

Figure 8.

Histology of transplanted GalT+/+ mouse hearts (H&E staining). (a) Histological findings of rejected GalT+/+ mouse heart 2 days after transplantation into control conditioned GalT–/– mouse that did not receive BMT, with interstitial hemorrhage and neutrophil infiltration. (b) Histological findings of rejected GalT+/+ mouse heart 12 days after transplantation into control conditioned GalT+/+ mouse, showing diffuse mononuclear cell infiltration. (c) Histological findings of GalT+/+ mouse heart 165 days after transplantation into GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimera. The graft shows no evidence of any type of rejection.

Figure 9.

Immunofluorescence staining for IgM, IgG, and C3 of transplanted GalT+/+ mouse hearts. Rejected GalT+/+ mouse heart 2 days after transplantation into control conditioned GalT–/– mouse that did not receive BMT shows endothelial deposition of IgM (a), IgG (b), and C3 (c). GalT+/+ mouse heart 165 days after transplantation into GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimera shows no deposition of IgM (d), IgG (e), or C3 (f).

Discussion

We demonstrate here the simultaneous induction of T-cell tolerance and specific tolerance of Gal-reactive B cells in GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimeras prepared with a relatively nontoxic, nonmyeloablative regimen. These results suggest that the successful induction of mixed hematopoietic chimerism with nonmyeloablative conditioning in the pig-to-human (GalT+/+→ GalT–/–) xenogeneic combination could lead to tolerance among Gal-reactive B cells, as well as T cells recognizing histocompatibility antigens. Although the pathophysiological consequence of losing anti-Gal antibodies needs to be determined (30), it seems probable that induction of specific tolerance will be associated with less risk of infection than the high level of chronic immunosuppression that would be required to prevent xenograft rejection.

For success to be achieved with this approach, the possible role that preexisting anti-Gal NAb’s may play in resisting GalT+/+ xenogeneic marrow engraftment must first be addressed. In this study, GalT–/– recipient mice with relatively high levels of preexisting anti-Gal NAb’s before BMT developed reduced GalT+/+ hematopoietic chimerism compared with GalT–/– recipients with lower levels of preexisting anti-Gal NAb’s (data not shown). However, once GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimerism was achieved in GalT–/– mice, it was stable, and, even if present at low levels (7–10% donor WBCs), it was associated with both B-cell and T-cell tolerance. Our findings suggest that anti-Gal NAb’s may have inhibitory effects on the engraftment of GalT+/+ BMCs, but that this degree of resistance can be overcome when sufficient GalT+/+ BMCs are administered. This speculation is also supported by our previous findings that the ability of murine sera to inhibit engraftment of rat BMCs was correlated with their cytotoxic anti-rat NAb content, and that their inhibitory effect could be overcome by administration of large numbers of rat BMCs (28, 31, 32). Consistent with these results, we have confirmed the feasibility of inducing mixed chimerism in GalT–/– mice with high levels of anti-Gal due to immunization with rabbit erythrocytes before conditioning. When high-dose BMT with GalT+/+ BMCs was given to such mice, chimerism and tolerance were achieved (H. Ohdan, K. Swenson, and M. Sykes, manuscript in preparation). If this approach were applied to the pig-to-human combination, previously reported strategies for reducing initial anti-Gal NAb and/or complement levels should be used to facilitate initial BMC engraftment. Despite such efforts, however, induction of persistent mixed chimerism has not yet been achieved in a pig-to-primate combination. In addition to the vigorous immune response to xenoantigens, nonimmune physiological factors (e.g., the failure of crucial growth factors, adhesion molecular interactions, and cytokines to function across species barriers) also limit the achievement of chimerism between discordant species (33). Some of these problems might be alleviated by the use of donor-specific growth factors and/or cytokines at the time of BMT (34), and others may require genetic engineering of donor pigs.

Our previous results involving induction of mixed chimerism in lethally irradiated mice demonstrated that newly developing anti-Gal–producing B cells could be tolerized by the presence of GalT+/+ hematopoietic cells (19). In contrast to lethal irradiation, the conditioning regimen used here would not be expected to eliminate preexisting anti-Gal–producing B cells (35, 36). Consistent with this possibility, we observed increasing anti-Gal NAb levels in sera of GalT–/– mice receiving nonmyeloablative conditioning without BMT. Thus, anti-Gal NAb–producing cells were present at high levels after conditioning. In contrast, anti-Gal–producing cells were already undetectable by ELISPOT assay in mixed chimeras as early as 2 weeks after BMT, suggesting that mixed chimerism induced tolerance among anti-Gal–producing cells that preexisted at the time of BMT. The cells that produce anti-Gal in GalT–/– mice have not been defined. However, if it is assumed that their half-life is similar to that of other murine mature B cells (6 weeks) (37) or plasma cells (as long-lived as memory B cells) (36), then it is likely that preexisting anti-Gal NAb–producing mature B or plasma cells are tolerized by the induction of mixed chimerism. Although mature B cells are generally thought to be less sensitive than newly developing cells to tolerance induction by self-antigens or foreign antigens (38), chronic exposure to antigenic determinants present on cell surfaces has been reported to eliminate mature B cells in immunoglobulin-transgenic mice (39, 40). Based on these results, it is likely that preexisting anti-Gal–producing cells are tolerized through antigen-receptor cross-linking in mixed chimeras. However, an alternative explanation for the rapid development of tolerance in mixed chimeras is that anti-Gal–producing B cells or plasma cells may have rapid turnover. Studies are in progress to distinguish these possibilities.

In mixed chimeras, Gal epitopes may be recognized as self-antigens during B-cell maturation. The known mechanisms mediating tolerance of self-reactive B cells include clonal deletion (i.e., the physical elimination of autoreactive B-cell clones) (38, 40–42), anergy (i.e., the functional inactivation of autoreactive B cells) (43, 44), and receptor editing (i.e., the modification of B-cell receptors of autoreactive cells) (45–47). To investigate the possibility that these mechanisms are also involved in maintaining Gal-reactive B-cell tolerance in mixed chimeras, we assayed the presence of B cells with receptors (sIgM) recognizing Gal epitopes. Using FITC-conjugated Gal-BSA, we could directly identify B cells bearing anti-Gal receptors in the spleens of normal GalT–/– mice (Figure 5a). Because anti-Gal–producing cells express sIgM (H. Ohdan and M. Sykes, unpublished data), the specificity of the Gal-BSA ligand for the corresponding receptors on B cells was demonstrated by showing enrichment of anti-Gal–producing cells among Gal-binding B cells and a complete absence of anti-Gal–producing cells among non–Gal-binding B cells, using combined FCM sorting and ELISPOT assay (Figure 5b). In mixed chimeras, B cells with receptors recognizing Gal were completely absent in the spleens (Figure 6), suggesting the possibility of clonal deletion and/or receptor editing of Gal-reactive B cells as a mechanism of tolerance.

In the present study, indefinite acceptance of vascularized GalT+/+ heart grafts was demonstrated in GalT+/+→GalT–/– mixed chimeras, whereas rapid vascular rejection was observed in untreated and conditioned control GalT–/– mice. Although the kinetics of GalT+/+ heart rejection in GalT–/– mice were delayed compared with the typical HAR that usually occurs within minutes to hours in pig-to-primate combinations (12, 48), the histological and immunofluorescence data are consistent with a role for anti-Gal in rejection. The role of antibodies in this process is further substantiated by the more delayed (cell-mediated) rejection observed in GalT+/+ to GalT+/+ mice with similar histoincompatibilities. The slower time course of GalT+/+ allogeneic mouse heart rejection observed in GalT–/– mice, compared with pig-to-primate transplantation, may be explained, first, by a lower inherent ability of mice to fix complement by the classical pathway and, second, by the intraspecies compatibility of complement regulatory proteins in our model. Using the GalT+/+ to GalT–/– mouse heart transplant model, other reports also demonstrate the absence of HAR (49) or the presence of DXR-like rejection (with graft survival of 8–12 days) (50). The more rapid rejection of allografts in control mice in our studies may be due to differences in the anatomical site of heart grafting, to the presence of MHC alloantigens in our donors, and, most probably, to the more advanced age of the mice in our studies, which was associated with high levels of anti-Gal antibodies at the time of heart grafting. Despite this rapid rejection in control mice, GalT+/+ heart allografts in mixed chimeras were free from all types of rejection, indicating the presence of tolerance at the level of both T and B cells. This is, to our knowledge, the first direct demonstration that the induction of mixed chimerism can simultaneously prevent both T cell– and antibody-mediated rejection of vascularized solid-organ grafts. Taken together with our previous results demonstrating the induction of T-cell tolerance across rat-to-mouse and pig-to-mouse species barriers induced by a regimen similar to that used in the present studies (51, 52), it could be expected that the successful induction of mixed hematopoietic chimerism in the pig-to-human xenogeneic combination would similarly result in T- and B-cell tolerance and acceptance of vascularized organ xenografts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D.K.C. Cooper and A.D. Thall for helpful review of the manuscript; D.H. Sachs for advice and encouragement; H.S. Kruger Gray for cell sorting assistance; and D. Plemenos for expert secretarial assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants POI HL-18646 and ROI HL-49915) and by a sponsored research agreement between Massachusetts General Hospital and BioTransplant Inc. H. Ohdan was partially supported by Naito Foundation.

References

- 1.Platt JL. Xenotransplantation: recent progress and current perspectives. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:721–728. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sachs DH. The pig as a xenograft donor. Pathol Biol. 1994;42:217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oriol R, Ye Y, Koren E, Cooper DKC. Carbohydrate antigens of pig tissues reacting with human natural antibodies as potential targets for hyperacute vascular rejection in pig-to-man organ xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 1993;56:1433–1442. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199312000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galili U. Interaction of the natural anti-Gal antibody with α-galactosyl epitopes: a major obstacle for xenotransplantation in humans. Immunol Today. 1993;14:480–482. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90261-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandrin M, Vaughan HA, Dabkowski PL, McKenzie IFC. Anti-pig IgM antibodies in human serum react predominantly with Galα1-3Gal epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11391–11395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leventhal JR, et al. Prolongation of cardiac xenograft survival by depletion of complement. Transplantation. 1993;55:857–865. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199304000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cozzi E, White DJG. The generation of transgenic pigs as potential organ donors for humans. Nat Med. 1995;1:964–967. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sablinski T, et al. Xenotransplantation of pig kidneys to nonhuman primates: I. Development of a model. Xenotransplantation. 1995;2:264–270. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon PM, et al. Intravenous infusion of Galα1-3Gal oligosaccharides in baboons delays hyperacute rejection of porcine heart xenografts. Transplantation. 1998;65:346–353. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199802150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandrin MS, et al. Enzymatic remodelling of the carbohydrate surface of a xenogeneic cell substantially reduces human antibody binding and complement-mediated cytolysis. Nat Med. 1995;1:1261–1267. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osman N, et al. Combined transgenic expression of α-galactosidase and α1,2-fucosyltransferase leads to optimal reduction in the major xenoepitope Galα(1,3)Gal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;94:14677–14682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper DKC. Xenoantigens and xenoantibodies. Xenotransplantation. 1998;5:6–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.1998.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galili U, Minanov OP, Michler RE, Stone KR. High-affinity anti-Gal immunoglobulin G in chronic rejection of xenografts. Xenotransplantation. 1997;4:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmetshofer A, Galili U, Dalmasso AP, Robson SC, Bach FH. α-galactosyl epitope-mediated activation of porcine aortic endothelial cells. Transplantation. 1998;65:844–853. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199803270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bach FH, et al. Barriers to xenotransplantation. Nat Med. 1995;1:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y, Goebels J, Xia G, Vandeputte M, Waer M. Induction of specific transplantation tolerance across xenogeneic barriers in the T-independent immune compartment. Nat Med. 1998;4:173–180. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Y, Vandeputte M, Waer M. Accommodation and T-independent B cell tolerance in rats with long term surviving hamster heart xenografts. J Immunol. 1998;160:369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaTemple DC, Galili U. Adult and neonatal anti-Gal response in knock-out mice for α1,3galactosyltransferase. Xenotransplantation. 1998;5:191–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.1998.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y-G, et al. Tolerization of anti–Galα1-3Gal natural antibody-forming B cells by induction of mixed chimerism. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1335–1342. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thall AD, Maly P, Lowe JB. Oocyte Galα1,3Gal epitopes implicated in sperm adhesion to the zona pellucida glycoprotein ZP3 are not required for fertilization in the mouse. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21437–21440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dialynas DP, et al. Characterization of murine T cell surface molecule, designated L3T4, identified by monoclonal antibody GK1.5: similarity of L3T4 to human Leu3/T4 molecule. J Immunol. 1983;131:2445–2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarmiento M, Glasebrook AL, Fitch FW. IgG or IgM monoclonal antibodies reactive with different determinants on the molecular complex bearing Lyt2 antigen block T cell-mediated cytolysis in the absence of complement. J Immunol. 1980;125:2665–2672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharabi Y, Sachs DH. Mixed chimerism and permanent specific transplantation tolerance induced by a non-lethal preparative regimen. J Exp Med. 1989;169:493–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sykes M, Abraham VS, Harty MW, Pearson DA. IL-2 reduces graft-vs-host disease and preserves a graft-vs-leukemia effect by selectively inhibiting CD4+ T cell activity. J Immunol. 1993;150:197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomita Y, Khan A, Sykes M. Role of intrathymic clonal deletion and peripheral anergy in transplantation tolerance induced by bone marrow transplantation in mice conditioned with a non-myeloablative regimen. J Immunol. 1994;153:1087–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherman LA, Randolph CP. Monoclonal anti-H-2Kb antibodies detect serological differences between H-2Kb mutants. Immunogenetics. 1981;12:183–189. doi: 10.1007/BF01561661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuura A, Abe T, Yasuura K. Simplified mouse cervical heart transplantation using a cuff technique. Transplantation. 1991;51:896–898. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199104000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aksentijevich I, Sachs DH, Sykes M. Natural antibody against bone marrow cells of a concordant xenogeneic species. J Immunol. 1991;147:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galili U, Rachmilewitz EA, Peleg A, Flechner I. A unique natural human IgG antibody with anti-galactosyl specificity. J Exp Med. 1984;16:1519–1531. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.5.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss RA. Transgenic pigs and virus adaptation. Nature. 1998;391:327–328. doi: 10.1038/34772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aksentijevich I, Sachs DH, Sykes M. Natural antibodies can inhibit bone marrow engraftment in the rat→mouse species combination. J Immunol. 1991;147:4140–4146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aksentijevich I, Sachs DH, Sykes M. Humoral tolerance in xenogeneic BMT recipients conditioned with a non-myeloablative regimen. Transplantation. 1992;53:1108–1114. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199205000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gritsch HA, et al. The importance of non-immune factors in reconstitution by discordant xenogeneic hematopoietic cells. Transplantation. 1994;57:906–917. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199403270-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y-G, et al. Donor-specific growth factors promote swine hematopoiesis in SCID mice. Xenotransplantation. 1996;3:92–101. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson RE, Warner NL. Radiosensitivity of T and B lymphocytes. III. Effect of radiation on immunoglobulin production by B cells. J Immunol. 1975;115:161–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, Ahmed R. Humoral immunity due to long-lived plasma cells. Immunity. 1998;8:363–372. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fulcher DA, Basten A. Influences on the lifespan of B cell subpopulations defined by different phenotypes. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1188–1199. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klinman NR. The “clonal selection hypothesis” and current concepts of B cell tolerance. Immunity. 1996;5:189–195. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murakami M, et al. Antigen-induced apoptotic death of Ly-1 B cells responsible for autoimmune disease in transgenic mice. Nature. 1992;357:77–80. doi: 10.1038/357077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell DM, et al. Peripheral deletion of self-reactive B-cells. Nature. 1991;354:308–311. doi: 10.1038/354308a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nemazee D, Buerki K. Clonal deletion of autoreactive B lymphocytes in bone marrow chimeras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8039–8043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartley SB, et al. Elimination from peripheral lymphoid tissues of self-reactive B lymphocytes recognizing membrane-bound antigens. Nature. 1991;353:765–769. doi: 10.1038/353765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodnow CC, et al. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B-lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;334:676–682. doi: 10.1038/334676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nossal GJV. Clonal anergy of B cells: a flexible, reversible, and quantitative concept. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1953–1956. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tiegs S, Russell D, Nemazee D. Receptor editing in self-reactive bone marrow B-cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1009–1020. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hertz M, Nemazee D. BCR ligation induces receptor editing in IgM+IgD- bone marrow B cells in vitro. Immunity. 1997;6:429–438. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pelanda R, et al. Receptor editing in a transgenic mouse model: site, efficiency, and role in B cell tolerance and antibody diversification. Immunity. 1997;7:765–775. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cooper DKC, et al. Effects of cyclosporine and antibody adsorption on pig cardiac xenograft survival in the baboon. J Heart Transplant. 1988;7:238–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKenzie IFC, Li YQ, Patton K, Thall AD, Sandrin MS. A murine model of antibody-mediated hyperacute rejection by galactose-α(1,3)galactose antibodies in Gal0/0 mice. Transplantation. 1998;66:754–763. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199809270-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearse M, et al. Anti-gal antibody-mediated allograft rejection in α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene knockout mice. A model of delayed xenograft rejection. Transplantation. 1998;66:748–754. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199809270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharabi Y, Aksentijevich I, Sundt TM, III, Sachs DH, Sykes M. Specific tolerance induction across a xenogeneic barrier: production of mixed rat/mouse lymphohematopoietic chimeras using a nonlethal preparative regimen. J Exp Med. 1990;172:195–202. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao Y, et al. Skin graft tolerance across a discordant xenogeneic barrier. Nat Med. 1996;2:1211–1216. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]