Abstract

The allometric-constraint hypothesis states that evolutionary divergence of morphological traits is restricted by integrated growth regulation. In this study, we test this hypothesis on a time-calibrated and well-documented palaeontological sequence of dental measurements on the Pleistocene arvicoline rodent species Mimomys savini from the Iberian Peninsula. Based on 507 specimens representing nine populations regularly spaced over 600 000 years, we compare static (within-population) and evolutionary (among-population) allometric slopes between the width and the length of the first lower molar. We find that the static allometric slope remains evolutionary stable and predicts the evolutionary allometry quite well. These results support the hypothesis that the macroevolutionary divergence of molar traits is constrained by static allometric relationships.

Keywords: dental morphology, evolutionary trend, evolutionary constraint, morphological integration, Lower Pleistocene, scaling relationship

1. Introduction

Huxley's [1,2] model of allometric growth provides a unifying theoretical framework to link within-species variational properties to morphological divergence. Based on the assumption that the growth rates of morphological traits are proportional to the growth of body size, this model predicts that the trait size, Y, will covary in the population with body size, X, according to a power relationship, Y = aXb, that becomes linear on a log scale: log[Y] = log[a] + b log[X] [2]. The value of the allometric slope b expresses the growth rate of the trait relative to the growth rate of body size [3–6].

The allometric scaling model occupies a key place in studies of developmental constraints on morphological evolution (e.g. [3,4]). Originally based on a developmental model, morphological allometry can be defined not only at the ontogenetic level, but also at the static and evolutionary levels, that is, within and among evolutionary units (i.e. populations, species or higher taxa), respectively. The allometric-constraint hypothesis postulates that the static allometric slope (b) remains stable at macroevolutionary timescales and is able to restrict the evolutionary divergence in morphospace along its specific trajectory (for reviews, see [5,6]). This narrow-sense static allometric slope may therefore be a specific case of a ‘genetic line of least resistance’ (sensu Schluter [7]) explicitly encompassing developmental or physiological constraints.

Nowadays, this hypothesis is often expressed in a quantitative-genetics framework, and it has been predicted that bivariate drift or selection on body size alone can generate an evolutionary allometric slope collinear with the genetic static allometric slope [8,9]. Recently, comparative studies have provided substantial arguments for the stability and the constraining role of the narrow-sense static allometric slope [6,10,11]. Few studies, however, have looked at the evolution of ontogenetic or static allometric slopes in the fossil record.

Although evolutionary sequences in the fossil record often display a stationary pattern [4,12,13], there are also many examples of lineages exhibiting apparent ‘trends’ of size change. These have been attributed to constant directional selection (e.g. [14]), undirected diversification from a lower size bound [15] or to release of constraints associated with the colonization of new ecological niches (e.g. [16]). Examples of bivariate evolutionary divergence of populations or species distributed along straight lines (on arithmetic or logarithmic scales) have been documented from early studies of fossil sequences (e.g. [17–20]) with the allometric constraint as a background hypothesis. However, the difficulty of estimating the static allometric slope from limited fossil samples, as well as the lack of adequacy of the approaches generally used [5, 6], have hampered evaluations of the allometric-constraint hypothesis from palaeontological sequences. Filling this gap requires accounting for time dependency of fossil samples and a dataset large enough to properly estimate both static and evolutionary allometries in order to compare them.

The molars of arvicoline rodents are well suited for the study of evolutionary trends in the fossil record. They are usually well-preserved fossils found in abundance in Neogene fossiliferous layers and they are complex and taxonomically diagnostic organs for which a large number of traits can be measured and compared (e.g. [21–24]). In the following, we test the allometric-constraint hypothesis by estimating how the static allometry predicts the evolutionary allometry between molar traits in a recently described 600 000 year-long fossil sequence for a Pleistocene arvicoline rodent species in the Iberian Peninsula [25,26].

2. Material and methods

(a). Samples

We reanalysed data from Lozano-Fernández et al. [25,26] describing 600 000 years of microevolutionary change of the first lower molar (M1) dimensions of the rodent species Mimomys savini. This extint arvicoline is considered as the first representative of the water-vole lineage (genus Arvicola). Mimomys savini occurred in Europe during the Early Pleistocene and beginning of the Middle Pleistocene, between 1.8 and 0.6 Ma [27–31]. In the Iberian Peninsula, the oldest record of this species is located in the deposits of the Guadix-Baza basin [32–34].

Mimomys savini exhibits evolutionary trends, including an increase in size, in both central Europe and the Iberian Peninsula [25,31,35–38]. However, individuals in the Iberian populations are systematically larger, as supported by the comparison of means from Lozano-Fernández et al. [25,26] with means from Maul et al. [31,36,37], suggesting separate evolutionary histories between the Iberian and Central-European lineages as expected from their geographical isolation [26]. Among Iberian populations, the tendency towards size increase was documented for both the length and the width of the first lower molar [25], suggesting a length–width evolutionary allometric relationship that motivated this study.

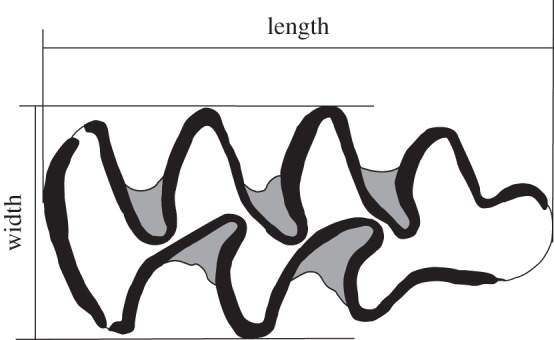

The fossil samples come from the Lower Pleistocene layers of different localities in Spain. As their ages coincide with early human dispersal events, the Iberian M. savini samples have indirectly benefited from absolute dating efforts providing an exceptionally long and high-quality chronology for a terrestrial Pleistocene lineage. The sequence consists of nine samples associated with absolute ages. Their chronology (table 1) was taken from Lozano-Fernández et al. [25,26] and updated according to recent absolute dating [39,40]. Molar length and width (figure 1) have been measured (in millimetres) for a total of 507 individuals as described by Lozano-Fernández et al. [25].

Table 1.

Ages, sample sizes (N), means and standard deviations (s.d.) for lower molar (M1) length and width for each population. Within-population (i.e. static) allometric slopes between molar width and length are reported with their standard errors (s.e.) and the coefficient of determination (R2). Static allometric relationships are estimated on log-transformed data using ordinary least-squares regression.

| molar length (mm) |

molar width (mm) |

static allometry |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| site names | age (Ma) | N | mean | s.d. | mean | s.d. | slope | s.e. | R2 |

| Barranco León 5 (BL-5) | 1.40 | 51 | 3.23 | 0.11 | 1.40 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| Fuente Nueva 3 (FN-3) | 1.19 | 61 | 3.28 | 0.11 | 1.41 | 0.08 | 1.02 | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| Gran Dolina (TD 4B) | 1.01 | 12 | 3.43 | 0.14 | 1.43 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.15 |

| Gran Dolina (TD 5b) | 0.99 | 137 | 3.47 | 0.14 | 1.47 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| Gran Dolina (TD 5a) | 0.96 | 104 | 3.49 | 0.14 | 1.49 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 0.25 |

| Gran Dolina (TD 6-3) | 0.86 | 101 | 3.43 | 0.17 | 1.49 | 0.09 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| Gran Dolina (TD 6-2) | 0.83 | 10 | 3.59 | 0.18 | 1.53 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.03 |

| Vallparadis (Vallp U10) | 0.83 | 22 | 3.49 | 0.15 | 1.54 | 0.07 | 0.50 | 0.19 | 0.25 |

| Gran Dolina (TD 6-1) | 0.80 | 9 | 3.62 | 0.20 | 1.51 | 0.08 | −0.15 | 0.36 | 0.02 |

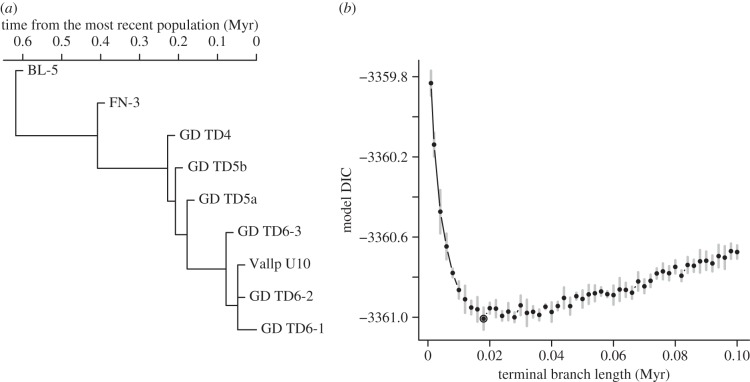

Figure 1.

Measurements taken on the first lower molar in occlusal view. Adapted from [25].

The number of sampled individuals per population ranges from nine to 137 (median: 51). Because five out of the nine samples have a size exceeding 50 individuals, this dataset is well suited to estimate static allometric slopes, and to assess their variation through time and their effect on evolutionary allometry. Some of the within-population variation in molar morphology may be due to variation in dental wear. For example, the complexity of the M1 occlusal outline has been shown to correlate with wear in arvicoline rodents [41]. In this study, however, extreme stages of wear were removed from the sample, and the parallel crown walls of the M. savini hypselodont M1 make wear unlikely to have a large influence on the length–width pattern of static allometry.

Here, we analysed the allometric relationship between the two traits, regressing the natural log width of the first molar on its natural log length.

(b). Statistics

We first estimated variation in static allometric slopes among populations with a mixed-effects regression model, fitted in the R package lme4 [42], with log of molar width as response variable, log of molar length as predictor variable and population as a random factor. Two models fitted with restricted maximum likelihood (REML) were compared using the Akaike's information criterion (AIC), one assuming a static allometric slope common for all populations and the other assuming a variable allometric slope across populations. This comparison allowed estimating the among-population differences in static allometric slopes. Because the common-slope model showed the best fit (see Results), we compared the evolutionary allometric slope to the common static slope. To estimate the evolutionary and the common static allometric slope, while accounting for phylogenetic relatedness among populations and measurement error in the population means, we fitted a bivariate Brownian-motion model of evolution using the MCMCglmm R package [43]. This model estimates the variance matrix between the two traits, log(width) and log(length), at both the among- and within-population levels. The evolutionary allometric slope (be) was estimated as the ratio of the traits' covariance to the variance in log molar length, based on the phylogenetically corrected among-population variance matrix. The common static allometric slope (bs) was equivalently estimated from the within-population variance matrix. From this model, we also estimated the contrast between the slopes at the two levels (i.e. be – bs) to test the allometric-constraint hypothesis. The model ran for 250 000 iterations including a burn-in of 50 000 iterations and a thinning interval of 200 iterations to minimize the level of autocorrelation in the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) resampling. For the variance matrices, we used scaled F-distributed priors, where the variances divided by 10 are F1,1 distributed. For the residuals, we used inverse-Wishart distributed priors with parameters V and n [43]. The matrix parameter V was set to a crude guess of the within-population variance matrix, while n was set to 1.002. Confidence intervals for the model parameters were obtained by MCMC resampling.

The expected among-population covariance structure was computed from a phylogeny of populations (handled with the ape R package [44]) separated along the stem by internal branches whose lengths correspond to the time elapsed between them (table 1 and figure 2a). To account for the possibility that the observed populations may not stand in a perfect ancestor–descendant relation to each other, or that an unquantified factor (e.g. geography) has influenced the ancestor–descendent divergence pattern, we added a non-zero branch length from the stem to each population. The length of this branch was treated as a parameter to be estimated. Hence, we assumed that the divergence from the stem was the same for all populations (except the terminal population) to keep the spacing of populations constant in time. To estimate the length of the branch, we assessed 50 values between 1000 and 100 000 years. Each model was run five times for each value. The best fit according to the deviance information criterion [45] (DIC, averaged over the five replicates) was a terminal branch length of 18 000 years (figure 2b). This was retained for the final analysis.

Figure 2.

(a) Combined phylogenetic tree used to estimate the evolutionary allometric slope for the mixed model (see table 1 for site abbreviations). (b) Change in the DIC of the MCMCglmm model according to the values added to the terminal branch length of the population phylogenetic tree in the left panel. Dots and error bars represent the means and standard deviations, respectively, of five MCMC runs for each terminal branch value (see Material and methods section for details). The terminal branch length retained in the final analysis equals 0.018 Myr given by the lowest DIC value (circled dot).

We evaluated whether the pattern of size increase in the molar measurements [25] can be attributed to a directional evolutionary process using Hunt's [46] maximum-likelihood framework for comparing models fitted to fossil time series. We fitted two models: (i) an undirectional Brownian motion and (ii) a directional Brownian motion including a trend parameter. The models were fitted to both log(length) and log(width) independently and compared for each trait with small-sample-corrected AIC values (AICc) in the paleoTS R package [46]. For these analyses, we used a model parametrization based on the joint distribution of mean trait values, because it performs better for detecting directional trends [47].

3. Results

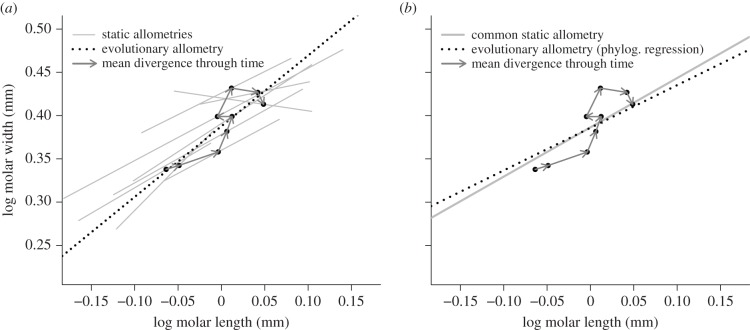

The least-squares estimates of the static allometric slopes varied across M. savini populations (table 1 and figure 3a). For the seven populations with a decent sample size (N > 20), the static slope ranged between 0.50 and 1.02, with a median of 0.58 (table 1; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). This variation may be due to estimation error, however, because the common-slope model fitted the data better that the variable-slope model (ΔAIC = 2.82).

Figure 3.

(a) Bivariate divergence and allometric slopes for the first lower molar (M1) within the M. savini lineage in the Iberian Peninsula. Arrows represent the transitions through time between population means (dark dots). Static allometric slopes for each population (table 1) and the ordinary least-squares evolutionary slope (dotted line, be = 0.81 ± s.e.: 0.18, R2 = 0.74) are also indicated. (b) MCMCglmm allometric estimates (table 2) displayed on the same graph. This illustrates the distribution of the population means around the common static allometric slope (grey) and the comparison to the evolutionary slope estimate (dotted line) accounting for the sampling error and the expected among-population covariance structure.

The common static allometric slope, bs = 0.57 (95% CI: 0.47–0.67), was close to the phylogenetically controlled evolutionary allometric slope be = 0.49 (95% CI: −0.11–1.16; table 2). This similarity can be expressed as a small and statistically non-significant contrast between the two slopes (be − bs = −0.08, 95% CI: −0.83–0.49; table 2). Figure 3b illustrates this pattern, showing that the directions of stepwise inter-population divergence through time in the bivariate plane roughly follow the common static allometric line, leading to an evolutionary allometry nearly collinear with the static allometry.

Table 2.

The static and the phylogenetically controlled evolutionary allometric slopes between molar width and length and their contrast. 95% confidence intervals for the parameters, coefficient of determination (R2, i.e. the squared correlation coefficient of the matrices) and p-values are estimated from the MCMC resampling for variances and covariances estimates.

| parameters | estimate | 95% CI | R2 | MCMC p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| static allometric slope (bs)a | 0.57 | 0.47 to 0.67 | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| evolutionary allometric slope (be) | 0.49 | −0.11 to 1.16 | 0.38 | 0.061 |

| contrast evolutionary versus static slope (be – bs) | −0.08 | −0.83 to 0.49 | — | 0.401 |

aThe equivalent REML estimates of the static allometric slope of the pooled within-population regression is 0.58 ± s.e. 0.05.

Between the first and the last point of the M. savini fossil sequence, the length and width of the first molar increased by 12% and 7%, respectively (table 1 and figure 3). For both molar length and width, the parameters of directional trends (μtrait ± s.e.) are small (μlog(length) = 0.15 ± 0.08; μlog(width) = 0.35 ± 0.32). Accordingly, the fit of a non-directional Brownian-motion model received a better support with lower AICc values for both molar length (ΔAICc = 2.00) and width (ΔAICc = 3.71). We also tested two other evolutionary models that showed worse fit. Relative to the Brownian motion, an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck model with a single optimum was worse with ΔAICc of 9.02 and 10.29 for M1 log(length) and log(width), respectively. Similarly, a white-noise model (‘stasis’) showed a worse fit with ΔAICc of 9.95 and 13.03, respectively.

4. Discussion

Comparing narrow-sense static allometric slopes within fossil populations with the evolutionary slope generated during population divergence over time is an intuitive way to test the allometric-constraint hypothesis. In the case of M. savini, we found that the static allometric slope between the length and the width of the first lower molar remains stable through time and predicts the evolutionary change observed over 600 000 years. Thus, the size increases previously described for both molar traits by Lozano-Fernández et al. [25,26] could be the result of morphological divergence constrained along a static allometric line. Despite its large standard error, the evolutionary allometry is very close to the static allometry, indicating that the allometric-constraint hypothesis is not falsified in this case. This is in accordance with the conclusions from the recent meta-analysis by Voje et al. [6] supporting a constraining role of static allometry on trait divergence on timescales less than a million years. Over larger time and taxonomic scales, larger changes in allometric coefficients are commonly observed [6], as claimed for rodent skull traits [48,49].

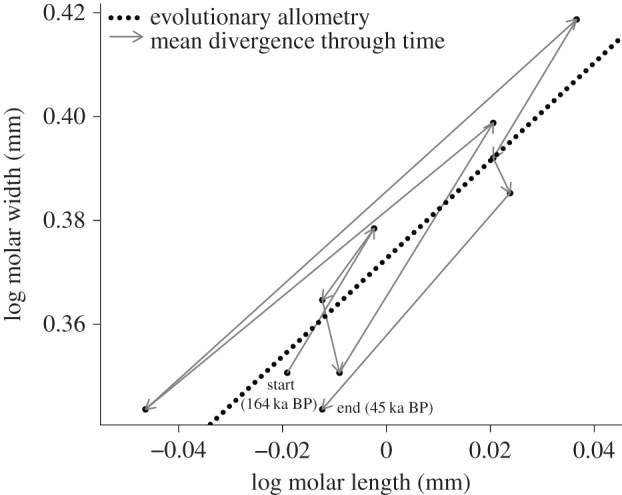

In figure 4, we reanalysed in a narrow-sense allometric context the data from Lich [24], describing a ca 119 000 year-long fossil sequence for the New World rodent species Cosomys primus, ‘a morphologically convergent form of the Eurasian Mimomys’ [38]. We found a strong M1 length–width evolutionary allometry (ordinary least-squares slope: be = 0.94 ± 0.15) close to the one estimated in M. savini (be = 0.81 ± 0.18, figure 3a). That an analogous pattern of relative trait divergence is observed independently in two distinct fossil lineages adds additional support to a role for allometric constraints in the evolution of molar proportions in rodents.

Figure 4.

Reanalysis of Lich's [24] data reporting the population averages for the length and the width of the first lower molar (M1) in the C. primus fossil time series (Middle–Upper Pleistocene) from North America. The ordinary least-squares estimate of the evolutionary allometric slope (dotted line) is be = 0.94 ± s.e. 0.15 (R2 = 0.82).

Evaluating previous work on allometric divergence in rodent molars is challenging because of the diversity of approaches, focal traits and definitions of allometry used by different researchers. Many discussions based on fossil time series have involved contrasting patterns between ‘size’ and ‘shape’, where size has been argued to be more evolutionary labile than shape (e.g. [12,14,50–52]). Such comparison can lead to meaningless conclusions if size and shape are expressed on different scales. In an elementary bivariate case as in the M. savini molar, shape is often assessed as a dimensionless ratio (e.g. width/length). Variation in such a ratio depends on the allometric relationship linking the two traits, since Y/X = aXb−1 [53], and the possibility for shape divergence among populations then depends on how much the evolutionary allometric slope deviates from isometry (i.e. from b = 1). In spite of a long history of critique [54], analyses focusing on ratios and their comparison to size generally ignore their intrinsically underlying allometry. To become meaningful, such comparisons would require standardization to a common scale, but how to do this is not obvious. We suggest it is better to work within the (narrow-sense) allometric framework to understand how the whole size–shape relationship is evolving.

Results from some previous studies indicate that allometry is a strong component of shape variation in rodent molars. For instance, in a fossil series of the arvicoline Terricola savii, the length-to-width ratio increased over time [23] and also varies among contemporary populations [55] indicating a length–width evolutionary allometry deviating from isometry (i.e. b ≠ 1). In Myodes glareolus [56], another arvicoline, and within the Arvicola genus [57], a strong effect of size on M1 shape suggests an analogous pattern. Other rodent taxa exhibiting a molar pattern convergent with arvicoline rodents could be informative. For instance, the spectacular elongation of the lower first molar found in the Mikrotia murine genus endemic to the Gargano palaeo-archipelago [58] could similarly be explained by a hypo-allometric constraint (i.e. b < 1) expressed during the size increase documented in some of these lineages [22,58] or result from selection imposed by a specific food regime. Evaluating allometric constraints in this taxon could shed light on how such an exaggerated dental morphology evolves.

With the caveat that the M. savini time series has a small number of sampling intervals and the power to detect evolutionary patterns is consequently low, we did not detect a trend or any more complex patterns in molar size evolution. Our tentative interpretation is thus that the molars diversify according to a Brownian motion along a fixed allometric relationship. We note, however, that the static allometries were far from tight. For the better sampled populations, the R2 ranges from 15 to 34% with a R2 of 20% for the estimated common slope. This does not fit well with the allometric-constraint hypothesis [6]. It is hard to see how a trait can be substantially constrained by another trait that only explains 20% of its variance. After all, 80% of the variance should be freely available for selection to change the traits away from the allometric relation. Part of the low R2 must be due to measurement error, which is unquantified in these data, but this can surely not explain the big pattern. This leaves us with the conundrum that we seem to find evidence for allometric constraints resulting from a weak allometric relationship. A possible solution to this conundrum may be to view the allometric relations as resulting from selective rather than genetic constraints. If both the evolutionary and the static allometries in M. savini have been shaped by similar selective pressures, then they would be similar even without a tight fit of the traits to the static allometry. This ‘adaptationist’ hypothesis posits that the populations are aligned along a selective ridge (sensu Armbruster & Schwaegerle [59]) that also imposes stabilizing selection on their static allometric slopes. This scenario matches Arnold et al.'s [60,61] concept of a ‘selective line of least resistance’. Thus, the static allometry could not only be a direct predictor of the most likely response to selection but also a local reflection of the dominant features of the adaptive landscape. In both cases, the consequence is that estimates of the static allometric slopes contain information to predict evolutionary divergence.

To summarize, we found that the relative evolutionary increase in the size of two molar traits in M. savini is consistently predicted by a static allometric relationship remaining stable over more than half a million year. We hope this result will encourage further investigations on other fossil time series for which allometric slopes can reliably be estimated at several levels.

Acknowledgements

This Spanish–Norwegian collaboration was initiated within the scientific team of the Bois-de-Riquet archaeological site (dir. L. Bourguignon and J.-Y. Crochet). We thank Gene Hunt and an anonymous referee for constructive comments on the manuscript. The sites’ excavation team has helped with the extraction, sieving and washing of sediments.

Data accessibility

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.mg0v4.

Funding statement

This work was supported by grant 196434/V40 from the Norwegian Research Council to C.P. at NTNU, a pre-doctoral grant from the Fundación Atapuerca assigned to the IPHES (Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social) and projects CGL2012-38358, CGL2012-38434-C03-01, BP2012-CGL38358 and CGL 2009-12703-C03-03 of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, SGR 2009-324 of the Generalitat de Catalunya and the University of Zaragoza, Gobierno de Aragon, European Social Fund.

References

- 1.Huxley JS. 1924. Constant differential growth-ratios and their significance. Nature 114, 895–896. ( 10.1038/114895a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huxley JS. 1932. Problems of relative growth. New York, NY: L. MacVeagh. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gould SJ. 1977. Ontogeny and phylogeny. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould SJ. 2002. The structure of evolutionary theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pélabon C, Firmat C, Bolstad GH, Voje KL, Houle D, Cassara J, Le Rouzic A, Hansen TF. In press. Evolution of morphological allometry. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. ( 10.1111/nyas.12470) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voje KL, Hansen TF, Egset CK, Bolstad GH, Pélabon C. 2014. Allometric constraints and the evolution of allometry. Evolution 68, 866–885. ( 10.1111/evo.12312). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schluter D. 1996. Adaptive radiation along genetic lines of least resistance. Evolution 50, 1766–1774. ( 10.2307/2410734) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lande R. 1979. Quantitative genetic analysis of multivariate evolution, applied to brain–body size allometry. Evolution 33, 402–416. ( 10.2307/2407630) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lande R. 1985. Genetic and evolutionary aspects of allometry. In Size and scaling in primate biology (ed. Jungers WL.), pp. 21–32. New York, NY: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voje KL, Hansen TF. 2013. Evolution of static allometries: adaptive change in allometric slopes of eye span in stalk-eyed flies. Evolution 67, 453–467. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01777.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voje KL, et al. 2013. Adaptation and constraint in a stickleback radiation. J. Evol. Biol. 26, 2396–2414. ( 10.1111/jeb.12240) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt G. 2007. The relative importance of directional change, random walks, and stasis in the evolution of fossil lineages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 18 404–18 408. ( 10.1073/pnas.0704088104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uyeda JC, Hansen TF, Arnold SJ, Pienaar J. 2011. The million-year wait for macroevolutionary bursts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15 908–15 913. ( 10.1073/pnas.1014503108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clyde WC, Gingerich PD. 1994. Rates of evolution in the dentition of Early Eocene Cantius: comparison of size and shape. Paleobiology 20, 506–522. ( 10.2307/2401232) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanley SM. 1973. An explanation for Cope's rule. Evolution 27, 1–26. ( 10.2307/2407115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith FA, et al. 2010. The evolution of maximum body size of terrestrial mammals. Science 330, 1216–1219. ( 10.1126/science.1194830) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould SJ. 1966. Allometry and size in ontogeny and phylogeny. Biol. Rev. 41, 587–638. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1966.tb01624.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newell ND. 1949. Phyletic size increase, an important trend illustrated by fossil invertebrates. Evolution 3, 103–124. ( 10.2307/2405545) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robb RC. 1935. A study of mutations in evolution. I. Evolution in the equine skull. J. Genet. 31, 39–46. ( 10.1007/BF02982278) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeve ECR, Murray PDF. 1942. Evolution in the horse's skull. Nature 150, 402–403. ( 10.1038/150402a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnosky AD. 1990. Evolution of dental traits since latest Pleistocene in meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) from Virginia. Paleobiology 16, 370–383. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maul LC, Masini F, Parfitt SA, Rekovets L, Savorelli A. In press. Evolutionary trends in arvicolids and the endemic murid Mikrotia: new data and a critical overview. Quat. Sci. Rev . ( 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.09.017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piras P, Marcolini F, Raia P, Curcio MT, Kotsakis T. 2009. Testing evolutionary stasis and trends in first lower molar shape of extinct Italian populations of Terricola savii (Arvicolidae, Rodentia) by means of geometric morphometrics. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 179–191. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01632.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lich DK. 1990. Cosomys primus: a case for stasis. Paleobiology 16, 384–395. ( 10.2307/2400797) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lozano-Fernández I, Agustí J, Cuenca-Bescós G, Blain H-A, López-García JM, Vallverdú J. 2013. Pleistocene evolutionary trends in dental morphology of Mimomys savini (Rodentia, Mammalia) from Iberian peninsula and discussion about the origin of the genus Arvicola. Quaternaire 24, 179–190. ( 10.4000/quaternaire.6587) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lozano-Fernández I, Cuenca-Bescós G, Blain H-A, López-García JM, Agustí J. 2013. Mimomys savini size evolution in the Early Pleistocene of south-western Europe and possible biochronological implications. Quat. Sci. Rev. 76, 96–101. ( 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.06.029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fejfar O, Heinrich W-D, Lindsay EH. 1998. Updating the Neogene rodent biochronology in Europe. In The dawn of the Quaternary (eds Van Kolfschoten T, Gibbard PL.), pp. 533–554. Mededelingen, The Netherlands: Instituut voor Toegepaste Geowetenschappen. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jánossy D. 1986. Pleistocene vertebrate faunas of Hungary. Developments in palaeontology and stratigraphy, 8. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rekovets L. 1994. Melkie mlekopitayushchie Antropogena yuzhnoy chaste vostochnoi Evropy [Small mammals from the Anthropogene of the southern part of East Europe]. Kiev, Ukraine: Naukova Dumka; [in Russian] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topachevskii VA, Skorik AF. 1977. Gryzuny rannetamanskoj fauny Tiligul‘skogo razreza (Rodents of the Early Taman fauna from the Tiligul Pit). Kiev, Ukraine: Naukova Dumka. 250 p. Kiev, Ukraine. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maul L, Masini F, Abbazzi L, Turner A. 1998. The use of different morphometric data for absolute age calibration of some South and Middle European arvicolid populations. Palaeontogr. Italica 85, 111–151. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agustí J. 1986. Synthèse biostratigraphique du plio-pléistocène de Guadix-Baza (Province de Granada, Sud-Est de l'Espagne). Geobios 19, 505–510. ( 10.1016/S0016-6995(86)80007-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agustí J, Arbiol S, Martín Suárez E. 1987. Roedores y lagomorfos (mammalia) del Pleistoceno Inferior de Venta Micena (depresión de Guadix-Baza, Granada). Paleontol. Evol. 1, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agustí J, Blain H-A, Furió M, De Marfá R, Santos-Cubedo A. 2010. The Early Pleistocene small vertebrate succession from the Orce region (Guadix-Baza Basin, SE Spain) and its bearing on the first human occupation of Europe. Quat. Int. 223–224, 162–169. ( 10.1016/j.quaint.2009.12.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viriot L, Chaline J, Schaaf A. 1990. Quantification du gradualisme phylétique de Mimomys occitanus à Mimomys ostramosensis (Arvicolinae, Rodentia) à l'aide de l'analyse d'image. C. R. Acad. Sci. 310, 1755–1760. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maul L. 1990. Biharische Kleinsäugerfunde von Untermaßfeld, Voigtstedt und Süßenborn und ihre chronologische Stellung im Rahmen der biharischen Micromammalia-Faunen Europas. PhD thesis, Humboldt University, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maul L, Masini F, Abbazzi L, Turner A. 1998. Geochronometric application of evolutionary trends in the dentition of fossil Arvicolidae. In The dawn of the Quaternary (eds van Kolfschoten T, Gibbard PL.), pp. 565–572. Mededelingen, The Netherlands: Instituut voor Toegepaste Geowetenschappen. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaline J, Brunet-Lecomte P, Montuire S, Viriot L, Courant F. 1999. Anatomy of the arvicoline radiation (Rodentia): palaeogeographical, palaecoecological history and evolutionary data. Ann. Zool. Fennici 36, 239–267. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toro-Moyano I, et al. 2013. The oldest human fossil in Europe, from Orce (Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 65, 1–9. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.01.012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duval M, et al. 2012. On the limits of using combined U-series/ESR method to date fossil teeth from two Early Pleistocene archaeological sites of the Orce area (Guadix-Baza basin, Spain). Quat. Res. 77, 482–491. ( 10.1016/j.yqres.2012.01.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markova EA, Smirnov NG, Kourova TP, Kropacheva YE. 2013. Ontogenetic variation in occlusal shape of evergrowing molars in voles: an intravital study in Microtus gregalis (Arvicolinae, Rodentia). Mammal. Biol. Z. Säugetierkunde 78, 251–257. ( 10.1016/j.mambio.2013.03.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bates D, Maechler M. 2010. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package v. 0.999375–35 See http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hadfield JD. 2010. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: the MCMCglmm R package. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22.20808728 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. 2004. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20, 289–290. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, Van Der Linde A. 2002. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 64, 583–639. ( 10.1111/1467-9868.00353) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunt G. 2006. Fitting and comparing models of phyletic evolution: random walks and beyond. Paleobiology 32, 578–601. ( 10.1666/05070.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hunt G. 2008. Evolutionary patterns within fossil lineages: model-based assessment of modes, rates, punctuations and process. In From evolution to geobiology: research questions driving paleontology at the start of a new century (eds Bambach RK, Kelley PH.), pp. 117–131. Boulder, CO: The Paleontological Society. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson LAB. 2013. Allometric disparity in rodent evolution. Ecol. Evol. 3, 971–984. ( 10.1002/ece3.521) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson LAB, Sánchez-Villagra MR. 2010. Diversity trends and their ontogenetic basis: an exploration of allometric disparity in rodents. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1227–1234. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.1958) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renaud S, Michaux J, Jaeger J-J, Auffray J-C. 1996. Fourier analysis applied to Stephanomys (Rodentia, Muridae) molars: nonprogressive evolutionary pattern in a gradual lineage. Paleobiology 22, 255–265. ( 10.2307/2401120) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hodell DA, Vayavananda A. 1993. Middle Miocene paleoceanography of the western equatorial Pacific (DSDP site 289) and the evolution of Globorotalia (Fohsella). Mar. Micropaleontol. 22, 279–310. ( 10.1016/0377-8398(93)90019-T) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wood AR, Zelditch ML, Rountrey AN, Eiting TP, Sheets HD, Gingerich PD. 2007. Multivariate stasis in the dental morphology of the Paleocene-Eocene condylarth Ectocion. Paleobiology 33, 248–260. ( 10.2307/4500150) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bonduriansky R, Day T. 2003. The evolution of static allometry in sexually selected traits. Evolution 57, 2450–2458. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01490.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurtén B. 1954. Observation on allometry in mammalian dentitions; its interpretation and evolutionary significance. Acta Zool. Fennica 85, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nappi A, Brunet-Lecomte P, Montuire S. 2006. Intraspecific morphological tooth variability and geographical distribution: application to the Savi's vole, Microtus (Terricola) savii (Rodentia, Arvicolinae). J. Nat. Hist. 40, 345–358. ( 10.1080/00222930600639249) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ledevin R, Michaux JR, Deffontaine V, Henttonen H, Renaud S. 2010. Evolutionary history of the bank vole Myodes glareolus: a morphometric perspective. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 100, 681–694. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2010.01445.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piras P, Marcolini F, Claude J, Ventura J, Kotsakis T, Cubo J. 2012. Ecological and functional correlates of molar shape variation in European populations of Arvicola (Arvicolinae, Rodentia). Zool. Anzeiger J. Comp. Zool. 251, 335–343. ( 10.1016/j.jcz.2011.12.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freudenthal M. 1976. Rodent stratigraphy of some Miocene fissure fillings in Gargano (prov. Foggia, Italy). Scr. Geol. 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Armbruster WS, Schwaegerle KE. 1996. Causes of covariation of phenotypic traits among populations. J. Evol. Biol. 9, 261–276. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.1996.9030261.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arnold S, Pfrender M, Jones A. 2001. The adaptive landscape as a conceptual bridge between micro- and macroevolution. Genetica 112–113, 9–32. ( 10.1023/a:1013373907708) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arnold SJ, Bürger R, Hohenlohe PA, Ajie BC, Jones AG. 2008. Understanding the evolution and the stability of the G-matrix. Evolution 62, 2451–2461. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00472.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.mg0v4.