Abstract

Learning metabolism inevitably involves memorizing pathways. The teacher’s challenge is to motivate memorization and to help students progress beyond it. To this end, students should be taught a few fundamental chemical reaction mechanisms and how these are repeatedly used to achieve pathway goals. Pathway knowledge should then be reinforced through quantitative problems that emphasize the relevance of metabolism to bioengineering and medicine.

The importance of metabolism is beyond dispute. Metabolic enzymes constitute up to 25% of genes in microbes and 10% of those in humans1,2. Collectively, these enzymes perform the remarkable feat of converting unreliable supplies of incoming nutrients into balanced amounts of energy and biomass precursors. In microbes, the activities of these enzymes can be intentionally rewired to produce high-value products, including biofuels3,4. In humans, undesired metabolic imbalances can lead to obesity, diabetes and cancer, and drugs that attempt to restore normal metabolite concentrations are among the most prescribed pharmaceuticals.

Given the intrinsic interest of many students in energy and medicine, metabolism should be one of the most popular topics in biochemistry. Sadly, this potential is rarely realized in the classroom. Instead, students typically memorize pathways, motivated by little more than surviving the upcoming exam. Even among scientists who are sufficiently interested in metabolism to come to our research talks, mention of ‘the pathways that tormented you as an undergraduate’ always earns a mix of nods and laughs. This has led some universities, including Harvard, to omit metabolism from their core undergraduate curricula and instead incorporate newer topics in chemical biology, such as signaling networks and chemical genetics.

Yet physics doesn’t skip over Newton’s laws because they are not the latest findings. It teaches them first and foremost because of their foundational importance. Similarly, metabolism is the foundation of biochemistry. Its products enable growth, information storage and movement. Its regulation is a primary goal of signaling networks. Conversely, metabolite concentrations are direct and pivotal inputs for signaling enzymes (for example, AMP kinase, target of rapamycin, histone acetylases and deacetylases and DNA methyltransferases). Thus, although the basic pathways of metabolism may be old news, their regulation is a hotter research topic than ever before. Remarkably, even for such universal pathways as the TCA cycle and pentose phosphate shunt, the mechanisms of flux control remain largely a mystery. Developing an integrated understanding of metabolic regulation is a grand challenge for the twenty-first century, of analogous importance to the initial pathway elucidations by Warburg, Krebs and their colleagues nearly 100 years ago.

With the current revival of interest in metabolism as a research topic5–7, the time is ripe to reconsider how we teach it to students. Over the past eight years of educating graduate students and sophomore undergraduates, we have developed a three-pronged strategy: First, we teach glycolysis and the TCA cycle, with a focus on their chemical design principles: what are the ‘goals’ of the pathways, and how does every reaction contribute to these goals? Second, we teach steady-state flux analysis (flux balance analysis), which provides an ideal opportunity to illustrate the interplay between catabolism and anabolism: what substrates are required to build different biosynthetic products, and how does central metabolism make these? And, finally, we consider regulation and adaptation: what pathways are active under different nutrient conditions, and what are the mechanisms for turning pathways on and off? Throughout, we engage students in problem solving, which is both more fun and more educational than rote memorization.

The chemical logic of glycolysis

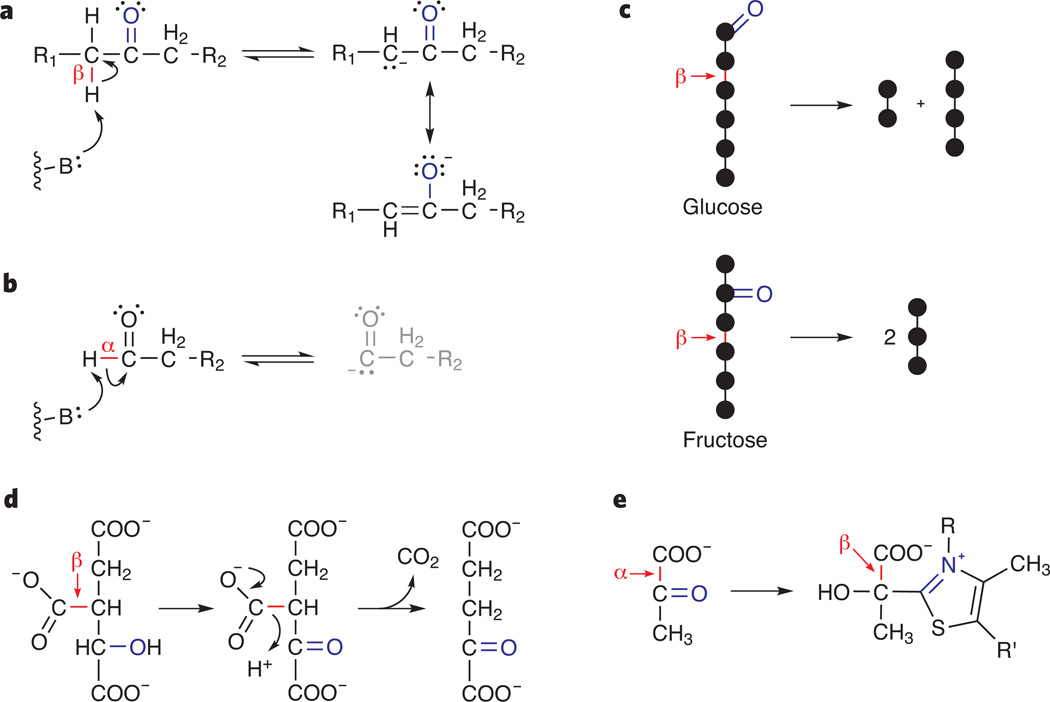

Our first educational goal is to illuminate the purpose of every individual reaction in glycolysis and the TCA cycle. To do this, we focus on three basic chemical principles: resonance stabilization, addition-elimination (to both carbonyls and phosphate) and reactivity of bonds β to carbonyl (Fig. 1a,b). These concepts are mentioned in current texts, but their importance is buried within detailed discussions of the catalytic mechanisms of individual enzymes8–11. We bring the principles to the forefront, using them to explain the means by which biology achieves its objectives given chemical reactivity constraints.

Figure 1.

Reactivity of bonds β to carbonyl. (a) Protons β to carbonyl are acidic because the conjugate base is resonance stabilized. The same resonance stabilization also renders C-C bonds β to carbonyl labile. B, generic base. (b) Protons α to carbonyl cannot be abstracted because the resulting conjugate base has no stable resonance forms. By the same logic, C-C bonds α to carbonyl cannot be broken or formed without cofactor involvement. (c) For glucose, C-C bond cleavage β to carbonyl would result in products with unequal numbers of carbon atoms, whereas for fructose it yields two trioses. In glycolysis, glucose is isomerized to fructose before it is cleaved. (d) Isomerization of citrate to isocitrate in the TCA cycle positions a hydroxyl group such that its subsequent oxidation to carbonyl enables production of α-ketoglutarate by C-C bond breakage β to carbonyl. (e) Decarboxylation of pyruvate requires C-C bond breakage α to carbonyl. This is enabled by addition of the cofactor thiamine to pyruvate’s carbonyl, which repositions the scissile C-C bond β to the ‘pseudocarbonyl’ (blue) of thiamine’s thiazolium ring.

Consider glycolysis, which achieves three important biological tasks: (i) energy production (ATP and NADH), (ii) biomass precursor synthesis (for example, 3-phosphoglycerate is the ‘parent’ molecule of serine) and (iii) breakdown of glucose into pyruvate, the substrate that feeds the TCA cycle. Glycolysis involves phosphorylating glucose twice, splitting it down the middle, oxidizing the resulting triose phosphates with concomitant high-energy phosphate bond formation and harvesting ATP from the doubly phosphorylated trioses.

The splitting of glucose into two identical trioses confers a beneficial simplicity to central metabolism: only a single lower glycolytic pathway is required, eliminating the need to synthesize and devote scarce cytosolic space to separate enzymes to metabolize asymmetric glucose fission products12,13. The role of hexokinase and phosphofructokinase in preparing for the splitting of glucose is straightforward: they install the phosphate groups that are needed to generate two molecules of triose phosphate. The purpose of phosphoglucoisomerase, however, is less clear. Why must glucose be isomerized into fructose before its cleavage into two trioses?

The importance of the phosphoglucoisomerase reaction is explained by our core principle of bond reactivity β to carbonyl. Bond breakage β to carbonyl involves transfer of the bonding electrons to the carbon atom adjacent to the carbonyl group (the α-carbon). The ability of the α-carbon to accept these electrons is explained by our core principle of resonance stabilization: the negative charge of the carbanion is largely transferred to the more electronegative oxygen atom of the carbonyl group (Fig. 1a; compare with bond α to carbonyl, Fig. 1b). This results in the reactivity of the bond β to carbonyl being ~1033 times greater than a hydrocarbon bond. This special reactivity underlies every C-C bond–breaking reaction in central metabolism. The purpose of glucose-to-fructose isomerization is to position the hexose’s carbonyl group such that its central bond is β to carbonyl, thereby allowing aldolase to generate two identical triose products (Fig. 1c).

Lower glycolysis further illustrates the importance of resonance stabilization. Its most remarkable enzyme is glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, which makes NADH and 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate. Both products are high energy because they lack resonance stabilization, whereas oxidation of NADH renders the nicotinamide ring aromatic, and cleavage of phosphate from 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate reveals a free carboxylic acid with two identical resonance forms.

How does the enzyme capture the favorable energy of aldehyde oxidation to make these two high-energy products? The answer involves our core reaction mechanism of addition-elimination. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase merely catalyzes two straightforward addition-elimination reactions, just with unusual nucleophiles and leaving groups. First, a thiol on the enzyme adds to the carbonyl of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, followed by elimination of hydride (H−), which is captured by NAD+. The thioester of the resulting enzyme-substrate complex is then attacked by inorganic phosphate, followed by elimination of the protein thiol as the leaving group. Though hydride is a miserable leaving group, and inorganic phosphate is a miserable nucleophile, the enzyme copes with this through substrate positioning. Current texts, some of which contain beautiful diagrams of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase reaction mechanism, nevertheless fail to convey the most important point for students: the enzyme is just carrying out a reaction type that they already know well: addition-elimination. Indeed, every reaction of glycolysis and the TCA cycle can be understood as some combination of bond breakage β to carbonyl and addition-elimination.

Repetition, repetition, repetition

Teaching the chemistry of central metabolism thus boils down to making students genuinely appreciate these two reaction mechanisms. Our preferred educational approach is to start with simple examples and build up to exciting brain teasers. Rather than leaping into the aldolase reaction, students need to first draw acetaldehyde, identify the acidic protons and draw the conjugate base and its resonance forms. Then the students can draw, using the arrow formalism, the condensation reaction of two acetaldehyde molecules. With this training fresh in their minds, most students can then appreciate the reaction mechanism of phosphoglucoisomerase (which relies on C-H bond breakage β to carbonyl) and of aldolase (which catalyzes C-C bond breakage β to carbonyl) and thus the overall chemistry of upper glycolysis. They can then be challenged to figure out the mechanisms of analogous reactions. Triose phosphate isomerase involves an identical reaction mechanism as phosphoglucoisomerase, and learning its mechanism is a good confidence builder. The pathway from citrate to α-ketoglutarate is slightly more challenging. Like upper glycolysis, it involves isomerization of the initial substrate to position the desired C-C bond β to carbonyl. The carbonyl, however, does not appear until oxidation of an appropriately placed alcohol just before C-C bond cleavage (Fig. 1d). Fatty acid synthesis provides a perfect opportunity to reinforce further the special reactivity of bonds β to carbonyl while also beginning to tie together catabolism and anabolism.

As students master the importance of reactivity β to carbonyl, they should become concerned about the decarboxylation reactions of pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate, which seem to involve C-C bond breakage α to carbonyl. Breaking these bonds would place a negative charge on the carbonyl carbon, with no resonance stabilization possible (Fig. 1b). To make these reactions feasible, enzymes use the cofactor thiamine. Thiamine reacts with the carbonyl of the substrates, generating an intermediate in which the scissile bond is positioned β to a ‘pseudocarbonyl’ (Fig. 1e).

Having been exposed to the role of thiamine, students can then learn the chemistry of the pentose phosphate pathway. The seemingly byzantine flow of the nonoxidative pentose phosphate pathway is actually the minimal set of reactions necessary to interconvert pentoses with glycolytic intermediates given the reactivity constraints discussed above14,15. A simple yet valuable student exercise is to identify all of the reactions that form or break C-C bonds in central metabolism, categorize them as α or β to carbonyl and mark which ones use the thiamine cofactor. The reactions β to carbonyl never use thiamine; those α to carbonyl always do. By understanding the recurring chemistry behind these apparently diverse reactions, students can begin to assemble a coherent picture of the importance of transformations throughout metabolism.

Balancing fluxes

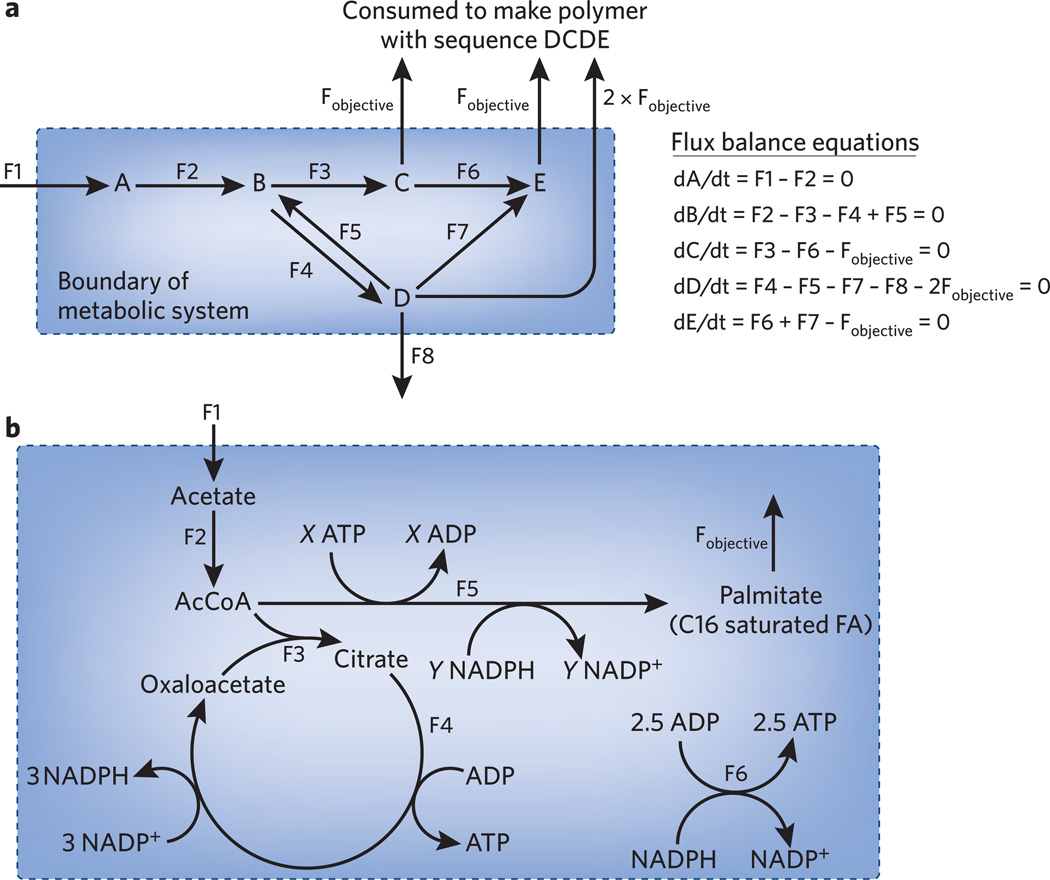

Chemical reactivity constraints help to explain why the current pathways evolved. What, however, can these pathways achieve? This question leads students to think about the integration of metabolic pathways throughout the cell and can be quantitatively answered, on the genome scale, by a modeling technique known as flux balance analysis16. The idea is straightforward: at steady state, whatever goes into a cell must come out (or become biomass). Mathematically, this idea is captured by expressing each metabolite’s rate of concentration change as a differential equation and setting all of these equations to zero. The resulting equations can be solved at the genome scale using matrix algebra techniques. In practice, however, a beginner’s knowledge of matrices and MatLab is sufficient to solve flux balance problems computationally. Moreover, no knowledge of matrices is needed to master the basic concepts and solve interesting problems.

In teaching flux balance analysis, we prefer to start with a toy network, an approach that we adopted from the technique’s innovators. For explaining the basic concepts, a small network is suitable (Fig. 2a). Once students grasp the main idea, real metabolic examples can be chosen that simultaneously reinforce pathway knowledge and analytical skills. For example, consider a mammalian cell growing under anaerobic conditions with glucose as the sole carbon source. What is the maximum fraction of incoming glucose that can be converted into glycogen? To answer this question, students need to write down the glycogen pathway, label the fluxes (F1, F2, F3 and so on) and write down flux balance equations for every metabolite in the system. In doing so, they will notice that certain metabolites (UTP, glucose-6-phosphate) cannot reach steady state because they are consumed but not produced. The students then need to pick relevant reactions from central metabolism to restore balance. The glycolytic pathway does almost the whole job, with nucleotide diphosphate kinase required to convert UDP to UTP. Less advanced students should be told to use nucleotide diphosphate kinase; more advanced ones can look up sources of UTP on the biocyc website (http://www.biocyc.org/). Because the system involves only two relevant branch points (Is glucose-6-phosphate directed toward glycogen or lactate? Is ATP used to phosphorylate glucose or UDP?), the flux balance equations can be solved quickly by hand to reveal an optimal yield of 0.5 glucose assimilated into glycogen per glucose consumed. A similar but harder problem, of genuine biofuel relevance, involves maximizing the conversion of acetate into fatty acids (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Example networks for teaching flux balance analysis. (a) Toy network. Students should learn to write down the flux balance equations shown to the right. They should then figure out, given F1 × 10 mmol h−1 and that all fluxes are positive (or zero), what is the maximum possible rate of synthesis of the tetramer DCDE (Fobjective). Note that the efflux from D to polymer synthesis is 2 × Fobjective because each tetramer contains two D monomers. The answer is a discrete value (2.5 mmol h−1) and can be achieved via multiple different sets of internal fluxes, always with F2 = 10 mmol h−1 and F8 = 0. (b) Metabolic network of biofuel relevance. Students should figure out the values of X and Y (7 and 14, respectively), write down the differential equations for all metabolites and set them equal to zero, and then maximize Fobjective. In this example, NADPH and ATP are assumed to be the sole cofactors for simplicity. AcCoA, acetyl CoA; FA, fatty acid.

Optimizing growth

One of the most striking findings of flux balance analysis is that Escherichia coli nearly maximize biomass production per molecule of carbon source consumed17. Such maximization requires optimally balancing carbon assimilation into biomass with carbon oxidation to generate ATP. Too much oxygen uptake reflects futile cycling (wasting of energy); too little reflects overflow metabolism (wasting of carbon). The optimal carbon/oxygen ratio can be calculated by genome-scale flux balance analysis. Much can be learned in a classroom setting, however, by trying to approximate the optimal carbon/oxygen ratio. A simple approximation begins by recognizing that E. coli biomass is more than half protein and that the average amino acid in protein contains roughly five carbon atoms. The question then becomes: how many ATP are needed to build the amino acid and incorporate it into protein, and what amount of carbon and oxygen is required to generate this ATP? In E. coli, most nitrogen is assimilated via glutamine synthetase, which consumes one ATP. tRNA charging consumes two ATP equivalents (one ATP → AMP), and the ribosome consumes two ATP equivalents per peptide bond (in the form of GTP). Thus, to put five carbon atoms into protein requires at least five ATP. Oxidative phosphorylation produces roughly 2.5 ATP per NADH or 5 ATP per oxygen. Full oxidation of one carbon of glucose generates the required two NADH. Thus, if one atom of glucose is oxidized to CO2, consuming one O2, enough ATP will be produced to put the other five carbon atoms into biomass. Impressively, this simple approximation, which illuminates the fundamental relationship between metabolism and growth, is correct within a factor of two (the actual ratio is just under two oxygen per glucose, in part reflecting ATP use also for cellular maintenance).

Mechanisms of flux control

A limitation of flux balance analysis is that it describes optimal fluxes but not the regulatory mechanisms necessary to achieve them. It is important to expose students also to the biochemical mechanisms of flux control. The Michaelis-Menten equation describes how enzyme and substrate concentrations affect metabolic flux. Students need to derive and practice using it. They should also recognize the role of transcription, translation and protein degradation in controlling enzyme concentrations (Vmax) and the possibility for allostery (involving either a small molecule–binding pocket or a covalent modification event) to affect either Vmax or Km. They should be able to differentiate competitive and noncompetitive inhibitors on the basis of graphs of reaction velocity versus substrate concentration.

Though it is very useful for studying the kinetics of isolated enzymes, the Michaelis-Menten equation is too simplified to accurately capture important aspects of actual cellular metabolism. Living cells are crowded with many different metabolites, which compete for the active sites of enzymes18. In addition, metabolic reactions often operate near equilibrium, violating the irreversibility assumption of the standard Michaelis-Menten equation. Accordingly, more advanced students also need to learn the reversible form of the equation, which includes product inhibition and can be readily expanded to include other competitive inhibitors:

where P stands for product, E stands for enzyme and S stands for substrate. This equation is the basis of many modern metabolic models, and interested students can be challenged to build computational models of different pathways and potential modes of regulation. Given the ubiquitous role of feedback inhibition in metabolism, a good exercise is to simulate a biosynthetic pathway with fixed concentrations of input metabolites, saturable end-product consumption (reflecting assimilation of the end product into biomass) and control of end-product concentration by feedback inhibition19. By tweaking parameters, students will observe that high end-product concentrations need not reflect high fluxes but can instead reflect slow use.

Biology provides a wealth of additional regulatory examples. Some of our favorites involve the bidirectional nature of lower glycolysis and the regulation needed for this pathway to alternate between the downward and upward directions. This switch involves the important concept of thermodynamic control of flux direction and the important enzymes pyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. It provides an ideal context for discussing feed-forward regulation (activation of pyruvate kinase by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate) and glucagon and insulin signaling.

The study of insulin signaling and pyruvate kinase leads naturally into cancer metabolism, an area of intense current inquiry20. Students will be fascinated to learn that the same kinase (Akt) that is activated by insulin to enhance cellular glucose uptake is also activated in most cancers. This duality reinforces the ties between metabolism and growth and provides a chance to introduce a topic of current media interest that students can also discuss at cocktail parties (Is sugar toxic? Does insulin cause cancer?)21.

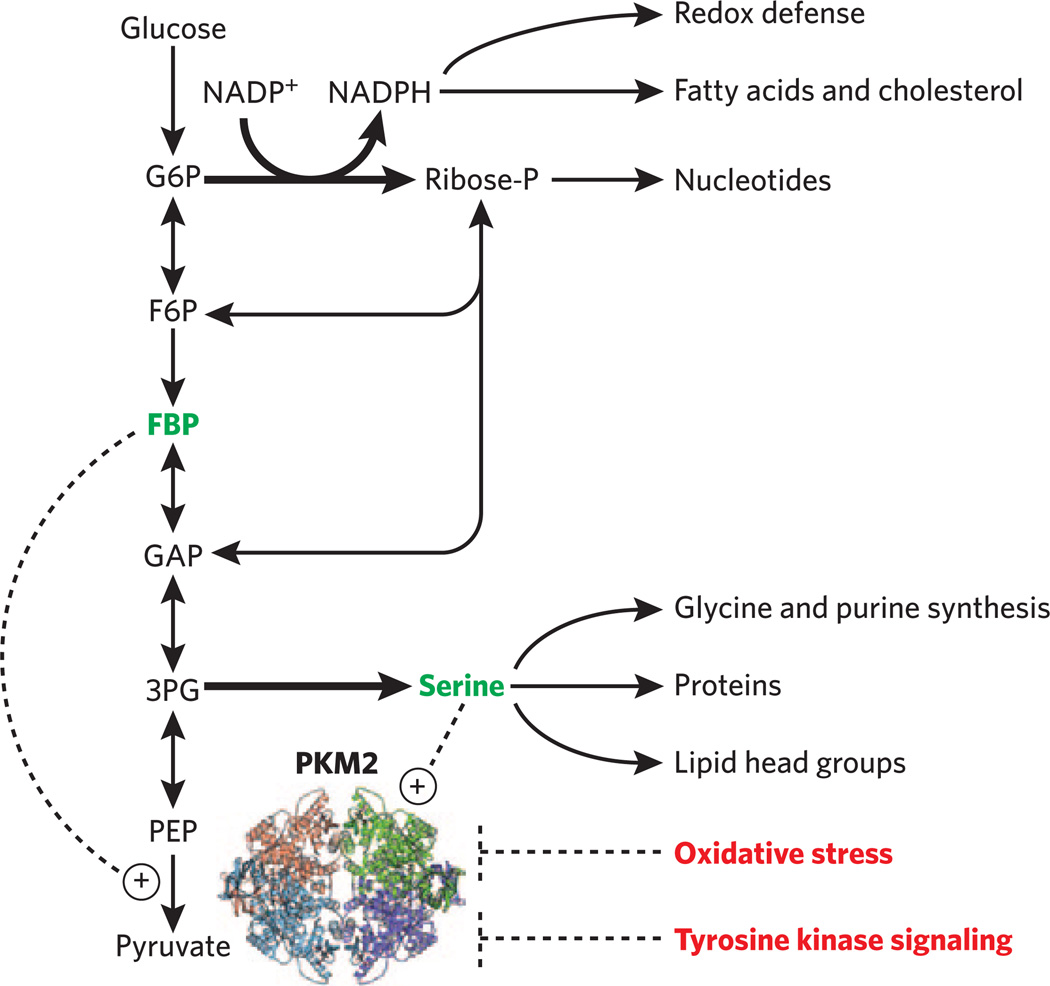

Students will similarly be surprised to learn that a specific isozyme of pyruvate kinase, the terminal glycolytic enzyme, can drive tumor growth22. All organisms encode in their genomes multiple copies of important metabolic enzymes. In E. coli there are two pyruvate kinase genes, and in humans there are three. Human cancer universally expresses a specific splice variant of one of these isozymes, known as pyruvate kinase isozyme M2 (PKM2). How does PKM2, which catalyzes the same reaction as the other more common pyruvate kinase forms, favor tumorigenesis? The answer seems to involve its ability to turn off in response to at least three signals: tyrosine phosphorylation, oxidative stress and low serine concentrations (Fig. 3). Turning off pyruvate kinase increases flux through the pentose phosphate pathway and serine biosynthesis, thereby providing NADPH for redox defense; ribose for nucleotide biosynthesis; and serine for protein, lipid and purine biosynthesis. There is intense current interest in figuring out the mechanisms that lead to formation of the PKM2 splice form in cancer23 and allow PKM2 to respond to these multifarious inputs24,25. In addition, major questions remain unanswered. For example, how does inhibition of pyruvate kinase increase pentose phosphate pathway flux and thus redox defense? In teaching metabolism, providing examples of unanswered questions is just as important as communicating the facts, as unanswered questions are the best motivation for students to engage in research.

Figure 3.

The cancer-associated pyruvate kinase isozyme (PKM2) offers a modern case study for teaching metabolic regulation by isozyme switching, allostery and covalent modification. PKM2 turns off in response to tyrosine kinase signaling, oxidative stress and low serine concentrations, thereby promoting flux through the oxidative pentose phosphate and serine biosynthetic pathways (bold arrows). These fluxes, in turn, drive tumor growth. Solid lines indicate metabolic fluxes (for simplicity, stoichiometry and some cofactors and reactions are not shown). Dashed lines indicate regulation. The mechanism by which pyruvate kinase inhibition increases pentose phosphate pathway flux remains unknown. Challenging students with unanswered questions can motivate them to engage in metabolism research. G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; ribose-P, ribose 5-phosphate.

Outlook

Learning metabolism is hard. No student succeeds without memorizing pathways. The educational challenge is to motivate memorization and provide context so that it results in enduring knowledge. In addition, it is critical to train students to apply pathway knowledge to solve problems. Carefully selected problems can simultaneously reinforce basic pathway knowledge, illustrate real-world relevance and teach valuable analytical skills. Many metabolic concepts are broadly applicable. For example, the framework of flux balance analysis is also used by major corporations to control the flow of goods from factories to stores.

A critical aspect of teaching metabolism is repetition. Every time that we teach a pathway, we gain a greater appreciation of its chemical elegance and biological importance. As students repeatedly see the same chemical concepts and pathways, they gain confidence, which in turn breeds interest and motivation for further study. Part of the beauty of metabolism is its interwoven nature, in which pathways work in concert to feed, drain and regulate each other. No introductory course can provide the comprehensive perspective necessary for full appreciation of this beauty—but it can provide a solid foundation onto which students can steadily build. In so doing, improved metabolism education will result in increasing numbers of students electing to pursue careers as metabolism-savvy chemical biologists.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shawn Campagna for help in designing this curriculum, David Botstein for his tireless support of innovative teaching, Bernhard Palsson for guidance teaching flux balance analysis, and NSF CAREER Award MCB-0643859 to J.D.R. for supporting the curriculum development.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Joshua D Rabinowitz, Email: joshr@princeton.edu, Department of Chemistry and Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA..

Livia Vastag, Department of Chemistry, Castleton College, Castleton, Vermont, USA..

References

- 1.Riley M. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:862–952. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.862-952.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duarte NC, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1777–1782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610772104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wargacki AJ, et al. Science. 2012;335:308–313. doi: 10.1126/science.1214547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellomonaco C, Clomburg JM, Miller EN, Gonzalez R. Nature. 2011;476:355–359. doi: 10.1038/nature10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiehn O. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002;48:155–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson JK, Connelly J, Lindon JC, Holmes E. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:153–161. doi: 10.1038/nrd728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patti GJ, et al. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:232–234. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehninger AL, Nelson DL, Cox MM. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. 4th edn. W.H. Freeman; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voet D, Voet JG. Biochemistry. 4th edn. Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrett R, Grisham CM. Biochemistry. 4th international edn. Brooks/Cole; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. Biochemistry. 6th edn. W. H. Freeman; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vazquez A, de Menezes MA, Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Futcher B, Latter GI, Monardo P, McLaughlin CS, Garrels JI. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:7357–7368. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meléndez-Hevia E. Biomed. Biochim. Acta. 1990;49:903–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noor E, Eden E, Milo R, Alon U. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:809–820. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feist AM, Palsson BO. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:659–667. doi: 10.1038/nbt1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibarra RU, Edwards JS, Palsson BO. Nature. 2002;420:186–189. doi: 10.1038/nature01149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett BD, et al. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:593–599. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goyal S, Yuan J, Chen T, Rabinowitz JD, Wingreen NS. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lustig RH, Schmidt LA, Brindis CD. Nature. 2012;482:27–29. doi: 10.1038/482027a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christofk HR, et al. Nature. 2008;452:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen M, David CJ, Manley JL. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:346–354. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hitosugi T, et al. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra73. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anastasiou D, et al. Science. 2011;334:1278–1283. doi: 10.1126/science.1211485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]