Abstract

As new magnetic nanoparticle-based technologies are developed and new target cells are identified, there is a critical need to understand the features important for magnetic isolation of specific cells in fluids, an increasingly important tool in disease research and diagnosis. To investigate magnetic cell collection, cell-sized spherical microparticles, coated with superparamagnetic nanoparticles, were suspended in 1) glycerine-water solutions, chosen to approximate the range of viscosities of bone marrow, and 2) water in which 3, 5, 10 and 100 % of the total suspended microspheres are coated with magnetic nanoparticles, to model collection of rare magnetic nanoparticle-coated cells from a mixture of cells in a fluid. The magnetic microspheres were collected on a magnetic needle, and we demonstrate that the collection efficiency vs. time can be modeled using a simple, heuristically-derived function, with three physically-significant parameters. The function enables experimentally-obtained collection efficiencies to be scaled to extract the effective drag of the suspending medium. The results of this analysis demonstrate that the effective drag scales linearly with fluid viscosity, as expected. Surprisingly, increasing the number of non-magnetic microspheres in the suspending fluid results increases the collection of magnetic microspheres, corresponding to a decrease in the effective drag of the medium.

Keywords: magnetic separation, magnetic nanoparticles, magnetic needle, rare cell detection

1. Introduction

Isolation of rare cells by specific characteristics, such as cell surface receptor expression, is an important tool for disease research and diagnosis (Dainiak et al 2007). Areas of medical research in which specific isolation by magnetic separation have been proposed include stem cell isolation from cord blood (Laitinen and Laine 2007), isolation and quantification of circulating tumors cells from solid tumors shed into blood (Mi et al 2011, Weissenstein et al 2012) and isolation of rare lymphoblasts from bone marrow in leukemia (Jaeteo et al 2009). As new utilities are discovered for isolating and quantifying cells collected from blood and bone marrow, there is a growing and critical need to understand the physical features important for collection.

Currently there are a number of methods focusing on the use of magnetic or superparamagnetic particles and magnetic sources to separate cells with a specific cell surface receptor from mixtures of cells. The simplest method involves the labeling of the target cells with magnetic particles and separation of the cells from the mixture using a strong magnet held against the side of the sample tube (Kuhara et al 2004, Matsunaga et al 2006, Stuckey et al 2006, Yoshino et al 2008, Kuhara et al 2009, Balmayor et al 2011). The targeted cells can then be collected by removing the fluid and nonmagnetic sample components, while the selected cells are held to the wall of the tube by the magnet. This simple separation method has been applied to both synthesized magnetic particles (Stuckey et al 2006, Balmayor et al 2011) and naturally occurring particles made from labeling magnetobacteria (Kuhara et al 2004, Matsunaga et al 2006, Yoshino et al 2008, Kuhara et al 2009) and to a wide variety of cell types including adipose and hematopoietic stem cells (Balmayor et al 2011, Kuhara et al 2009), mononuclear cells (Kuhara et al 2004), dendritic cells (Matsunaga et al 2006) and transplanted cells (Stuckey et al 2006).

More complex methods have also been developed which involve the use of column based technology in combination with magnetic particles. Columns can be used both with commercially available magnetic particles (Sukumar et al 2006, Said et al 2008, Peh et al 2012, Weissenstein et al 2012) or custom made magnetic particles (Majewski et al 2013, Shahbazi-Gahrouei et al 2013). Columns have been used both for positive selection based on cell surface markers (Carroll and Al-Rubeai 2005, Sukumar et al 2006, Shahbazi-Gahrouei et al 2013) and for negative selection through the depletion of cells expressing a particular maker (Said et al 2008, Peh et al 2012). Column methodologies have also been automated and commercially available systems have been used for the isolation of T cells from human leukapheresis samples (Hoffmann et al 2006). In addition to column based technologies, microfluidic technology has been applied for positive selection (Pamme and Wilhelm 2006), and a quadrupole magnetic sorter has been designed for enrichment of rare circulating tumor cells through the depletion of normal blood cells from the sample (Lara et al 2004). Although complex in construction, modern microfluidic devices and other flow-through technologies frequently yield high capture efficiencies (>80%), but high shear rates must be avoided to ensure cell viability, which may limit the separation rate in some flow-based applications. (Pratt et al 2011)

Here we examine a simple method involving the collection of magnetic nanoparticle-coated polystyrene microspheres, which mimic nanoparticle-coated cells, using a magnetic needle (Bryant et al 2007, Adolphi et al 2009, Jaetao et al 2009) inserted into the sample fluid. The size of the polystyrene spheres were chosen to be 9.65 μm, within the 7–12 μm size range for white blood cells, a common target for cell collection out of blood and bone marrow. The coating of the sphere by amine groups allows for uniform attachment of nanoparticles to the surface of the sphere. These uniform spheres enable a well-controlled model of cellular collection without the concern of variations in cell surface antigen expression, variations in cell size within a population, or the potential for internalization of the targeted nanoparticles by the cell, factors which have previously been identified in the literature as affecting magnetic cell separation (McCloskey et al 2003).

The magnetic needle geometry was originally designed to enable in vivo insertion, in place of a conventional (non-magnetized) bone marrow biopsy needle, in future clinical applications.[Jaetao 2009] For in vitro applications, the magnetic needle geometry has proved to have a number of advantages in terms of ease of use, effectiveness, and low cost. Extracting cells that adhere to the thin plastic sheath surrounding the needle is accomplished by raising the needle from the sample fluid, a much faster procedure than the removal of the fluid and non-magnetic components of the sample. The inexpensive plastic sheath is then removed from the needle, and the magnetic cells are rinsed from the sheath into the tip of a small plastic tube, resulting in a small volume (near point source geometry) suitable for subsequent magnetic detection by magnetic relaxometry. The entire procedure (separation and detection) can be completed in a few minutes, and the separation technology is simple and very inexpensive and non-damaging to cells.

The collection rate for a particular vessel geometry and a stationary array of magnets can be modeled, for example, with a Monte Carlo simulation, and the collection efficiency computed numerically as a function of collection time for a given set of assumptions regarding the properties of the labeled cells, the magnetic nanoparticles, and the suspending fluid. Previous studies have also modeled magnetic separation of cells based on magnetic collection by external magnets below or attached to the sides of a collection vessel (Babinec et al 2010) or in fluid flow (Haverkort et al 2009). However, our system is unique in focusing on the insertion of a magnetic needle into the center of the fluid in a non-flowing system. In this study, we include experimental data, in addition to modeling, to allow refinement of the model. We demonstrate that the collection efficiency vs. time is well-described by a simple analytic formula that can be conveniently scaled to determine relative properties when comparing the collection of cells under different conditions. Further, we show that the analytic formula is easily modified to account for the initial collection of magnetic cells that occurs over the brief period (<<1 s) while the needle is being plunged into the fluid, a phenomenon not accounted for in the Monte Carlo simulations of a stationary needle.

2. Materials and Experimental Methods

2.1. Magnetic needle and sample geometry

As shown in Fig. 1, the needle consists of ten 2 mm diameter cylindrical NdFeB magnets, 2 mm long, separated by nine non-magnetic stainless steel spacers, 2 mm diameter, 1 mm long. The magnets, all polarized in the same direction along the axis of symmetry with their spacers, are enclosed in a nonmagnetic stainless-steel tube with a wall thickness of 0.19 mm. The magnets are held in place inside the tube by a thin film of epoxy on the bottom and a stainless-steel rod, the handle of the needle, fitting snugly inside the steel tube at the top. A removable collecting sheath of polyimide with 0.1 mm wall thickness, with a water-tight epoxy seal about 3 mm long on the bottom, is slipped over the needle. The overall diameter of the sheathed needle is then 2.58 mm. The sample vessel is a clinical blood sample tube, glass of 10 mm inside diameter, with a hemispherical bottom and the axis of symmetry aligned vertically. The sample tube contains a 3 ml uniform suspension of cell-sized spheres. When the needle is inserted, the fluid level rises 2.8 mm, with the tip of the polyimide sheath resting on the bottom of the tube. The needle's flux density was measured using a F. W. Bell Gauss/Teslameter Model 5070 in 1 mm increments along the long axis of the needle, starting at the tip.

Figure 1.

Collection geometry showing the magnetic needle in the clinical blood sample tube.

2.2. Preparation of magnetic nanoparticle-labeled microspheres

Uniform 9.65 (± 0.25) μm diameter polystyrene spheres functionalized with carboxyl polymer (Bangs Laboratories, Inc., Fishers, IN) were covalently linked to 100 nm diameter amine-functionalized silica-coated superparamagentic iron oxide nanoparticles (SIMAG-amino, Chemicell, Berlin, Germany). Covalent linkage was done using standard carbodiimide chemistry, described briefly here. Five milligrams of polystyrene spheres were aliquoted into a 15 ml conical tube (Greiner Bio-One, San Diego, CA) and brought to a total volume of 10 ml with double distilled water. N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS) (Pierce, Rockford, Il) and 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (Pierce) were prepared fresh at a concentration of 25 mg/ml each in separate tubes with double distilled water. One hundred μl each of the EDC and Sulfo-NHS were added to the spheres and incubated at room temperature on a LabQuake shaker (LabIndustries, Inc., Berkeley, CA) for 20 minutes. Ten mg of SIMAG-amino nanoparticles were added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature on a LabQuake shaker for 2 hours. The sphere-nanoparticle mixture was centrifuged at 1,000 relative centrifugal force (RCF) for 10 minutes. The supernatant containing the unbound nanoparticles was removed, and 10 ml of double distilled water was added to the pelleted spheres. The centrifugation parameters were repeated once more, and the supernatant was removed. The remaining pellet was resuspended in a total volume of 2 ml double distilled water.

2.3. Preparation of fluids with varying viscosity

Samples with varying viscosity were created to mimic bone marrow, the viscosity of which is reported to be around 40 mPa-s in humans (Gurkan and Akkus 2008). To cover a range of possible biological viscosities, including blood, solutions were created using glycerine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and double distilled water to be 1, 10, 40 and 100 mPa-s. Mixtures were prepared by weight based on the ambient temperature of the laboratory on the day of testing using a table (“Viscosity of Aqueous Glycerine Solutions in Centipoises”) from Dow Chemical Corporation (https://dow-answer.custhelp.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/3600/~/optim-glycerine-viscosity). To these solutions, 3×106 nanoparticle-labeled microspheres were added.

2.4. Preparation of fluids containing a varying percentage of magnetic microspheres

For the creation of samples with varying percentages of magnetic nanoparticle-labeled spheres, it was important to keep the total number of magnetic spheres the same to allow comparison between samples. So for each sample, 3×106 magnetic nanoparticle-labeled microspheres were added to 2 ml of double distilled water to which a variable number of non-magnetic 9.65 micron polystyrene spheres (Bangs Laboratories) was added. After addition of the non-magnetic microspheres the total volume was adjusted to 2.8 ml with double distilled water. The number of non-magnetic microspheres added was calculated to achieve percentages of magnetic microspheres of 100%, 10%, 5% and 3% of the total microspheres present in the 2.8 ml solution.

2.5. Needle collection method and collection efficiency measurements

Fluid samples containing magnetically-labeled spheres for collection by the magentic needle were placed in a 3 cm3 clinical blood sample tube, described above, and mixed just prior to magnetic needle insertion. The clinical sample tube was placed into the magnetic needle holder with the top removed. As the needle was inserted into the sample tube, a timer was started and the needle was removed upon completion of the collection time. The needle sheath (to which the collected material adheres) was then removed and placed into a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube. The Eppendorf tube was placed under a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) sensor system to measure the magnetic moment of the collected magnetic material. The SQUID sensor system, magnetic relaxometry detection method, and analysis have been described in detail previously (e.g., Hathaway et al 2011). Once the magnetic measurement was completed, the sheath was dipped back into the clinical sample tube and swirled around to rinse off the collected spheres prior to the next needle collection. To compute the observed needle collection efficiency, we divided the measured magnetic moment (m) of the material collected at time t by the total measured magnetic moment (mtotal) of the prepared sample prior to needle insertion.

The 100 nm Chemicell SIMAG nanoparticles used in this study yield a magnetization of 0.99 J/T/kg[Fe3O4] measured by magnetic relaxometry; for comparison, the saturation magnetization of bulk magnetite is 92 J/T/kg, and a previous lot of 100 nm SIMAG particles measured by static magnetic susceptometry yielded a saturation magnetization of 72.9 J/T/kg. (Adolphi et al 2009) Thus, the magnitude of the relaxing magnetic moment detected by the SQUID system represents of order 1% of the total (static) magnetic moment of the magnetite nanoparticles. Following a 40 G magnetizing pulse, the 7-channel SQUID array detects the relaxation of the nanoparticle magnetization in zero field, and only those nanoparticles that exhibit relaxation times that fall within the measurement time window of the system are detected. (Adolphi et al 2009) In particular, the 50 ms detector dead time (the interval between the end of the magnetizing pulse and the beginning data collection) means that any particles with characteristic relaxation times << 50 ms are not detected, while the finite duration of the magnetizing pulse (~1 s) means that particles with long relaxation times are not fully magnetized and contribute minimally to relaxation detected during the data collection period. In the current study, the needle collection efficiencies are the ratio of two magnetic relaxometry measurements, each with the same ~1% sensitivity, so the calculated efficiencies do not depend on the sensitivity. Although the magnetic relaxometry technique is sensitive to of order 1% of the nanoparticles, the magnetic moments of all nanoparticles contribute to the static magnetic forces on the spheres.

3. Mathematical Modeling

3.1. Magnetic cells in a viscous medium in an applied field

3.1.1. Collection times

Assume cell-sized spheres, each decorated with n magnetic nanoparticles with an average magnetic moment μ. The average hydrodynamic radius of the spheres is a. They are suspended in a solution with viscosity η at temperature T. Each cell experiences a magnetic force , where B is the magnitude of the magnetic flux density produced at the cell by the needle (Bryant et al 2007). The argument of the Langevin function L is x = μB / kT. Since the Reynolds number is very small in this case, ~ 3×10−3, the spheres are moving at their terminal velocities ν, being acted on as well by a drag force fd = κν, where the drag coefficient is given in the simple case by Stokes's Law, κ = 6πηa. The two forces are equal and opposite at the terminal velocity so that

| (1) |

We can lump the sphere and fluid properties together and write

| (2) |

where c = nμ / κ. The time t for a sphere to go from point A to point A' in the fluid is just

| (3) |

Notice in Eq. 3 that depends on the location of the cell because varies with position. Since c has no spatial dependence, we can pull it out of the integral. Thus ct depends only on the geometry, μ, T, and the spatial dependence of .

| (4) |

It is important to note that Eq. 4 implies that the efficiency of any magnetic needle for collecting magnetic cells in any vessel is invariant (remains the same, independent of the properties of the suspending fluid and magnetic cell characteristics, excepting T and μ) when plotted vs ct. This means that once the efficiency is computed, or measured, for a particular choice of c and the time dependence determined, the efficiency for such magnetic particles in any other fluid medium may be determined by scaling, described below. Although we illustrate this result using a particular needle design and collecting volume, the scaling property is universal for any such magnetic collection device.

3.1.2. Collection efficiency

Now let us take the locus of points A to be the on the boundary of the volume inside of which all the spheres will reach the points A' located on the collecting sheath of the needle, in a time less than or equal to the collecting time t. Call the volume whose outside surface is defined by the locus of A and whose inside surface is defined by the locus of A' to be the fluid volume V (ct) from which all magnetic spheres are collected in time t, for the magnetic spheres whose lumped parameters comprise c. If V0 is the total volume of the fluid suspension in the collecting vessel, the collection efficiency is defined as eff = V (ct) / V0.

3.1.3. Scaling

Since the efficiency is a function of the product ct, we see that, if a model calculation is made for an assumed value of c and an experimental measurement of the efficiency is on a time scale t', then one can determine the parameters of the spheres (including the drag force) by the constant c' = ct / t'. That is, the efficiency function for a given collection geometry is invariant with the properties of the suspending fluid when plotted along a scaled time axis.

3.2. Monte Carlo modeling of the collection efficiency

3.2.1. The magnetic field produced by the needle

Using methods previously discussed (Bryant et al 2007), the magnetic field produced by the needle geometry illustrated in Fig. 1 is plotted in contour in Fig. 2, illustrating the field for half of the needle, the other half being the mirror image. The strength of the computed flux density was normalized to to be consistent with the flux density measured at specific locations, as described in the methods section.

Figure 2.

The contour projection of the cylindrical magnetic field of the needle shown in Fig. 1. The z axis is the axis of cylindrical symmetry The contours are lines of constant absolute values of the flux density B. There is a factor of 2 between adjacent lines. The contour line intersecting the z axis at 18.6 mm corresponds to 106 Gauss or 10.6 mT. Only one half of the field distribution is shown; the other half would be the mirror image attached to the rho axis at z=0. The pronounced minima, that in fact extend exactly to zero, are concentric rings around the axis of symmetry where the fields from the array of magnets precisely cancel to produce “equatorial singularities,” or nulls. With the method we have used to compute the field, the values in the magnet interiors (at radii less than 1 mm) give only the depolarizing field, and do not represent the full flux density. These regions are of course inaccessible to the magnetic spheres.

3.2.2. Parameter scaling factor

The value of the parameter c = nμ / 6πηa, used in the MonteCarlo calculations, 4.09×10−6 m2/T-s, is based on the quantities given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical properties of magnetically-labeled spheres.

| n | number of nanoparticles per cell-sized sphere | 105 |

| μ | average magnetic dipole moment per nanoparticle | 3.85×10−18 J/T |

| η | viscosity of the suspending fluid | 10−3 Pa-s |

| a | average hydrodynamic radius of the spheres | 5×10−6 m |

3.2.3. The Monte Carlo method

In order to model the fraction of magnetized nanoparticle-coated spheres collected onto the polyimide sheath of the needle in a given time interval, we wrote a code that begins with 4000 magnetic spheres distributed uniformly throughout the sample tube volume according to algorithm-generated random numbers. For each starting point, Eq.1 is numerically integrated for a given duration. If the sphere is found to have arrived at the collecting sheath during this duration, the sphere is deemed collected. For technical reasons, not all of the 4000 starting spheres participate; for example, those starting points that are inside the needle are discarded. For a given collecting time t, the collection efficiency will be defined as the number of spheres that arrive at the needle divided by the the number that started in the fluid volume.

3.2.4. The Langevin function

We performed the computation of the needle efficiency with and without the inclusion of the Langevin function in Eq.1 and found that the inclusion of the Langevin function had only a small effect on the outcome. The Monte Carlo results presented in Fig. 3 include the Langevin function in the calculation. However, we have neglected the effective weakening of the magnetic nanoparticle's coupling to the field of the needle, arising from the finite time required for the magnetic moment to reorient itself parallel to the magnetic field, given by the Neel relaxation time.(Victora 1989)

Figure 3.

The data points are the results of the Monte Carlo simulations including the Langevin function. The error bars are based on the statistics of the number of “starters” and “finishers” whose ratio determines the efficiency. The precision of the simulated data can be improved with longer computer runs. The solid line is a fit to the Monte Carlo results utilizing an analytical formula (Eq. 5).

3.3. Semiempirical model

3.3.1. Simple semiempirical formula

Remarkably, the Monte Carlo computation results for needle efficiency eff, in the present geometry, shown in Fig. 1, can be described well by a very simple, physically motivated formula:

| (5) |

where the best fit parameters a(1) and a(2) are 0.080 and 0.45, respectively, when the Langevin function is included. Note that the exponent of time, a(2), is near 2/5, which one would expect for a cylindrical dipole-like field falling off as the inverse cube of the radius, as follows. Consider a cylindrical geometry, with a fixed dipole on the symmetry axis, in which a free particle is suspended in a viscous fluid with a dipole moment at a distance r from the axis. The time t for the particle to come to the axis is determined by the reciprocal of its velocity and ν is proportional to the gradient of the magnitude of the field produced by the axial dipole (). The velocity ν then goes as 1/r4, because ▽B ∝1/ r4, and the time t to reach the axis is proportional to r5, given that. The cylindrical volume of particles collected is proportional to r2 (V =π · r2 · length). Therefore the volume enclosed within the radius r, and thus the needle efficiency, is proportional to the collection time raised to the 2/5 power (t2/5 ∝ r 2).

3.3.2. Semiempirical formula with needle insertion correction

As our experimental results show (see Fig. 3 below), the initial rapid insertion of the needle into the sample fluid results in a considerable collection of magnetically-labeled spheres, prior to t = 0 (the moment at which the needle is stationary in the sample fluid and the collection time t begins to elapse). We determined by trial and error that this initial collection that occurs while the needle is being inserted can be modeled by introducing into Eq. 5 an additional parameter multiplying the exponent, the constant a(3) :

| (6) |

3.3.3. The meaning of the parameters a(1), a(2) and a(3)

In Eqs. 5 and 6, the parameter a(1) plays a role similar to c in Eq. 4. For this reason we must raise both a(1) and t to the power a(2) for purposes of scaling. We expect a(1) to be proportional to c. Therefore, the drag of the suspension must be inversely proportional to a(1), whereas a(2) must not vary with drag. Since the initial accumulation on the needle during its plunge into the fluid volume most likely would depend on drag and possibly other factors, we keep a(3), like a(1), as a parameter to be fit for each separate time course. Since a(2) must be more global in its nature (not dependent on drag), we fitted a(2) globally when analyzing the results of each of the two experimental studies reported below.

4. Results

4.1. Efficiency vs. collection time

To facilitate the understanding of the collection of magnetic nanoparticle-coated cells from biological fluids, and to compare the developed mathematical model to actual collection, two data sets were obtained in which the collection efficiency (defined as the fraction of magnetic spheres collected) was determined as a function of the collection time. The experimental conditions were chosen to address two potential factors that could significantly affect the collection of rare cells from human body fluids. The first factor is the viscoscity of the fluid from which the magnetic cells are being collected, and the second factor is the potential for abundant unlabeled cells to affect the collection of rare magnetically-labeled cells. For each data set, three separate runs were made for 10 different collection times for four different conditions. One data set was obtained using nanoparticle-coated polystyrene spheres suspended in water with four different admixtures of glycerine. As blood and bone marrow are common biological fluids from which cells are collected, and water has a lower viscosity than these biological fluids, glycerine-water mixtures were selected to cover the range of viscosities reported for bone marrow and blood (Gurkan and Akkus 2008). The second data set was obtained using magnetic nanoparticle-labeled polystyrene spheres suspended in water into which different concentrations of unlabeled (i.e. non-magnetic) polystyrene spheres were added. As many biological applications propose to collect rare cells from a larger population of other types of cells, we added an excess of unlabeled polystyrene spheres to simulate the presence of untargeted cells in a mixture with the target cells of interest.

From examination of the data collected from these experimental samples, it was immediately clear that Eq. 5 would not fit the data. The salient difference between the simple mathematical model (shown in Fig. 3) and the experimental data (shown in Fig. 4) is the significant fraction of labeled spheres collected at the 5 second collection time in the experimental data. Based on the 5 second data, it appears that the collection efficiency of the needle does not extrapolate to zero at t = 0, as does the Monte Carlo computation. It was obvious from these data that the initial collection process must therefore be addressed. As the needle is being plunged into a sample tube containing the suspension of magnetic spheres it collects magnetic material, so that even at t=0, when the needle is first held stationary in the fluid, the collection efficiency is already greater than zero. The initial collection that occurs while the needle is being lowered into position is dependent on the fluid conditions and can be as high as 50%. This intial collection is addressed by adding the needle insertion factor a(3), resulting in Eq. 6, as described above.

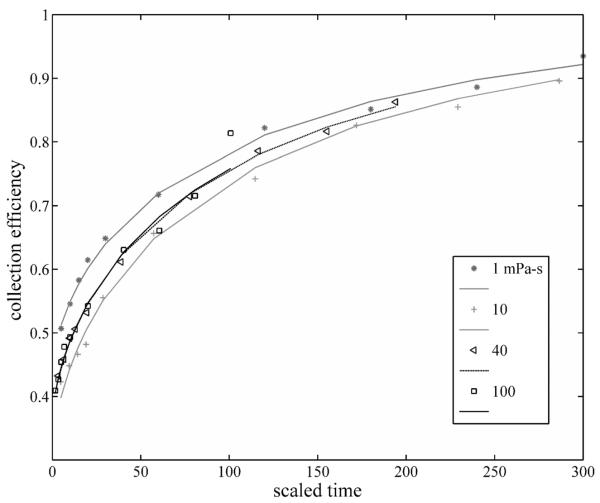

4.2. Scaled data

Figs. 5a and 5b display the fits of the semiempirical formula to the two data sets. One can see clearly that the scaling of the collection times collapses the four different drag conditions in each case to one curve that is reasonably consistent with the measurement uncertainties. In all cases the data were normalized to a fitted total possible collectable magnetic moment of 3.3×105 pJ/T.

Figure 5a.

The data of Fig. 4a, plotted vs. the scaled collection time.

Figure 5b.

The data of Fig. 4b, plotted vs. the scaled collection time.

4.3. Relative drag

4.3.1. Determination of relative drag

The raw measurements for each suspension of magnetically-labeled spheres consist of the measured collection efficiency for 10 different collection durations, taken in 3 separate time courses, producing 30 independent data points. The semiempirical model with the needle insertion correction (Eq. 6) was used to determine relative drag as follows: For each of our two experiments, varying viscosity and varying percentage of magnetic spheres, one sample condition was a suspension of magnetic spheres in pure water (no glycerine, no additional unlabeled spheres). Dividing the reciprocal of a(1) obtained for pure water by the reciprocal of a(1) obtained for each of the other experimental conditions yields 4 relative drags, the one for pure water we define as 1 and the three others accompanied by estimated uncertainties, as shown in Figs. 6a and 6b.

Figure 6a.

Relative drag on magnetically labeled microspheres in water-glycerine suspensions whose viscosity is given in centiPoise. The error bars are computed based on the expected range of errors in the individual points. The best estimate of the relative drag is at the center of the error bar. As expected, the dependence of relative drag on viscosity is consistent with a straight line (shown in gray) to within the experimental error.

Figure 6b.

Relative drag on magnetic microspheres, suspended in water, in the presence of additional non-magnetic microspheres. The total number of magnetic microspheres is the same in all four cases; the fraction of microspheres that are magnetic is given by “percent magnetic.” Note that the total number of microspheres in suspension decreases as the percent magnetic value increases. The experimental uncertainty in the relative drag is indicated by the values determined when the exponent, a(2), is varied by about approximately one standard deviation, consistent with other estimates we have made for these data. In fitting the data from which the drag was extracted we find that goodness of fit is appreciably worse for the data point at 5% magnetic, possibly explaining why this point seems to be less consistent in magnitude with the decline in drag exhibited by its neighbors.

4.3.2. Estimates of uncertainties in the relative drag

For each triplet of collection efficiencies corresponding to a particular collection time and sample condition, the standard deviation of the mean was determined. From these data, twenty-five possible outcomes were generated by multiplying the standard deviation of the mean for each time by a Gaussian-distributed random number (standard deviation 1) and adding the products to each of the original triplets. The standard deviations of the estimated relative drags are the error bars in Figs. 6a and 6b.

4.3.3. Relative drag vs. viscosity

Fig. 6a displays the results of fitting Eq. 6 to the varying viscosity data set. In this case, the normalized reciprocal of a(1) is linearly proportional to viscosity, as described in 3.3.3 above, indicating that relative viscosity can be extracted from measurements of the needle collection efficiencies.

4.3.4. Relative drag vs. percent magnetic spheres

Fig. 6b displays the results of fitting Eq. 6 to the percent magnetic data set. In this case, the normalized reciprocal of a(1), shown to be proportional to viscosity in Fig. 6a above, actually decreases as the number of unlabeled (non-magnetic) spheres was increased. Note that a higher percent magnetic corresponds to a smaller total number of spheres in solution because the absolute number of magnetic spheres was fixed. We expected a monotonic dependence of the relative drag on the percentage of magnetic spheres; however, the experimental data were inconsistent. Based on this small data set, it appears that the collection efficiency at 5% magnetic (measured in triplicate) is anamolously high, relative to the 3% and 10% measurements, and the source of this variability is not well-understood, although we note that the goodness of fit was poorer for the 5% magnetic data, relative to the other concentrations. Importantly, we expected that increasing the total number of spheres (lower percent magnetic value) would lead to an apparent increase in viscosity (i.e., an increase in 1/a(1)), because we assumed that the presence of non-magnetic spheres would tend to hinder the ability of the magnetic spheres to reach the magnetic needle. Thus, the most notable aspect of these results is that the dependence of the relative drag appears to show the opposite dependence, namely that the presence of greater numbers of non-magnetic spheres reduces the relative drag for all concentrations studied. We note that even in the sample containing the greatest number of unlabeled spheres (the 3% magnetic sample), the volume fraction of all spheres relative to the total volume of the medium was only 1.7%. A much higher volume fraction of unlabeled spheres may be required to increase drag appreciably. Further experiments will be required to elucidate the mechanism underlying the unexpected reduction in drag.

5. Concluding remarks

From a functional perspective, in a model system which can be well-controlled, we have examined the effect of two common confounding factors, viscosity and the presence of unlabeled “cells,” in the collection of magnetically-labeled rare cells from biological fluids. When the collection of nanoparticle-labeled spheres was examined in a set of glycerine/water samples designed to mimic the viscosity of human blood and bone marrow, we have shown that greater than 60% efficiency of collection is obtained within the first 30–120 seconds over a biologically-relevent range of viscosities using our current magnetic needle design and sample container geometry. The increase in efficiency over time is slower after the initial 60 seconds, as demonstrated by the limited increase in efficiency in the collection time experiments. The efficiency is strongly affected by the action of the needle being plunged into the collection vessel, as demonstrated by the experimental data which extrapolate to a non-zero value of collection efficiency at t = 0.

Our system performs with at least 60% capture efficiency (depending on viscosity) for the collection of rare cells from 3 ml of sample in under 2 minutes, outperforming a moving magnetic rod-shaped separator (MagSweeper) of similar design, which yields 50% efficiency for capturing circulating tumor cells with a fluid processing rate of 9 ml per hour. (Talasaz et al 2009) Our system does not perform as well as the more complex quadrupole Halbach magnet described by Babinec et al (2009), who report ~99% efficiency for collecting magnetic microspheres from a 2.8 cm diameter water sample in 20 s; for magnetic microspheres in water, our system yields >90% efficiency in 3 minutes. Compared to the magnetic needle, more complex microfluidic separation technologies generally perform with comparable or better capture efficiencies (Pratt et al 2011) using comparable fluid processing rates (typically 1 – 5 ml/minute); Loutherback et al (2012) report an 85% efficiency for capturing tumor cells from blood at a relatively high flow rate of 10 ml/minute.

In this study, examination of the data from samples to which increasing numbers of nonmagnetic spheres were added demonstrated that the collection efficiency of the magnetic needle was not reduced as the number of nonmagnetic spheres was increased. These data suggest that the viscosity of the biological fluid has a greater effect on the collection efficiency when compared to the concentration of nonmagnetic cells, for the cell volume fractions studied here (<1.7%). Taken together, these data suggest that a short exposure, on the order of 30–120 seconds, of magnetically-labeled cells to a magnetic needle in a clinical blood sample tube is sufficient for collection of at least 50% of the magnetically-labeled cells from the sample, regardless of the presence of unlabeled cells and the viscosity of the biological specimen.

Using a semi-empirical model to describe the collection efficiency, we have shown that the collection efficiency of the magnetic needle scales based on the parameter 1/a(1). Figs. 5a and 5b demonstrate the validity of this scaling, showing that, within experimental errors, the data collapse onto one “scaled” curve. This scaling is most useful in comparing the relative drag in experimental measurements in which only one variable is changed.

This semi-empirical model has been used to determine the relative drag, in suspensions of magnetic spheres in 1) a suspending fluid whose viscosity was altered by additions of glycerine, and 2) in a suspending fluid altered by increasing the number of unlabeled spheres in the presence of a constant number of magnetically-labeled spheres. The relative drag increased in proportion to the viscosity, as expected. Counterintuitively, the relative drag appears to decrease as the number of unlabeled (non-magnetic) spheres increases. This unexpected result, suggesting that the presence of additional inert surrounding bodies in the suspension decreases the drag, merits further investigation. We suggest that non-magnetic rigid plastic spheres may act like ball bearings with respect to the movement of the magnetic spheres attracted toward the magnet, and this effect may or may not be recapitulated by real cells, which are deformable and may be subject to attractive surface interactions due to the presence of proteins which may interact with serum proteins or proteins on other cells. The polystyrene sphere system utilized here provides the advantages of uniform size, uniform nanoparticle coating, and a long shelf life, and may therefore be useful in future studies aimed at examining other features of importance in cellular collection identified from the literature, including the effects of varying the size of the “cells,” the size and quantity of the nanoparticles attached, and the size and geometry of the collection tube. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that significant modifications of the surface of the plastic spheres, for example a soft coating and/or the addition of proteins, may be required in order more effectively mimic conditions under which cell-cell interactions significantly impact the collection efficiency.

The results of the current study support the results of a previous study investigating magnetic needle collection of rare magnetically-labeled cells (lymphoblasts) from real biological fluids (blood and bone marrow). (Jaetao et al 2009) Using the same needle design and collection protocol investigated here, the fraction of lymphoblasts in the cells collected on the needle was enhanced by as much as 10-fold relative to the blast fraction in the original sample. The observed fold-enhancement was greatest for samples with the lowest concentration of magnetically-labeled blasts and a high concentration of non-magnetic cells. (Jaetao et al 2009) In conclusion, using a simply-constructed magnetic needle, in both the model experimental system investiagted here and in patient samples, effective concentration of rare magnetically-labeled spheres or cells was achieved using a short collection time (of order 1 minute), which is expected to be an advantage in the clinical setting.

Figure 4. a.

Measured magnetic moment as function of collection time for different vicosities. Each point is the average of three trials, with the error bars the standard deviations of the means.

Figure 4b.

Varying percentages of magnetic nanoparticle-labeled microspheres suspended among non-magnetic spheres of the same size. The number of magnetic spheres is the same for all samples.

Table 2.

Best fit parameters obtained from the semi-empirical scaling formula.

| Viscosity | a(1) | a(2) | a(3) |

| 1 mPa-s | .0079 | 0.65 | 0.56 |

| 10 mPa-s | .0077 | 0.65 | 0.69 |

| 40 mPa-s | .0053 | 0.65 | 0.64 |

| 100 mPa-s | .0029 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Percent Magnetic | a(1) | a(2) | a(3) |

| 100% | .017 | 0.385 | 0.77 |

| 10% | .036 | 0.385 | 0.79 |

| 5% | .019 | 0.385 | 0.75 |

| 3% | .049 | 0.385 | 0.92 |

Acknowledgements

Senior Scientific, LLC, acknowledges the support of the NIH SBIR program (Award R44 CA105742). NLA acknowledges equity interests in ABQMR, Inc., and nanoMR; neither company sponsored this research.

References

- Adolphi NL, Huber DL, Jaetao JE, Bryant HC, Lovato DM, Fegan DL, Venturini EL, Monson TC, Tessier TE, Hathaway HJ, Bergemann C, Larson RS, Flynn ER. Characterization of magnetite nanoparticles for SQUID-relaxometry and magnetic needle biopsy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009;321:1459–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2009.02.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babinec P, Krafčík A, Babincová M, Rosenecker J. Dynamics of magnetic particles in cylindrical Halbach array: implications for magnetic cell separation and drug targeting. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2010;48:745–53. doi: 10.1007/s11517-010-0636-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmayor ER, Pashkuleva I, Frias AM, Azevedo HS, Reis RL. Synthesis and functionalization of superparamagnetic poly-ε-caprolactone microparticles for the selective isolation of subpopulations of human adipose-derived stem cells. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2011;8:896–908. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant HC, Sergatskov DA, Lovato D, Adolphi NL, Larson RS, Flynn ER. Magnetic needles and superparamagnetic cells. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007;52:4009–25. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/14/001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll S, Al-Rubeai M. ACSD labelling and magnetic cell separation: a rapid method of separating antibody secreting cells for non-secreting cells. J. Immunol. Methods. 2005;296:171–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dainiak MB, Kumar A, Galaev IY, Mattiasson B. Methods in Cell Separations. Adv. Biochem. Engin./Biotechnol. 2007;106:1–18. doi: 10.1007/10_2007_069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey NE. The Properties of Ordinary Water Substance. Reinhold; New York: 1940. p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Gurkan UA, Akkus O. The Mechanical Environment of Bone Marrow: A Review. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2008;36:1978–91. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway HJ, Butler KS, Adolphi NL, Lovato DM, Belfon R, Fegan D, Monson TC, Trujillo JE, Tessier TE, Bryant HC, Huber DL, Larson RS, Flynn ER. Detection of breast cancer cells using targeted magnetic nanoparticles and ultra-sensitive magnetic field sensors. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R108. doi: 10.1186/bcr3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkort JW, Kenjereš S, Kleijn CR. Magnetic particle motion in Poiseuille flow. Physical Review E. 2009;80:016302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.016302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann P, Boeld TJ, Eder R, Albrecht J, Doser K, Piseshka B, Dada A, Niemand C, Assenmacher M, Orsó E, Andreesen R, Holler E, Edinger M. Isolation of CD4+CD25- regulatory T cells for clinical trials. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:267–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaetao JE, Butler KS, Adolphi NL, Lovato DM, Bryant HC, Rabinowitz I, Winter SS, Tessier TE, Hathaway HJ, Bergemann C, Flynn ER, Larson RS. Enhanced leukemia cell detection using a novel magnetic needle and nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8310–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhara M, Takeyama H, Tanaka T, Matsunaga T. Magnetic cell separation using antibody binding with Protein A expressed on bacterial magnetic particles. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:6207–13. doi: 10.1021/ac0493727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhara M, Yoshino T, Shiokawa M, Okabe T, Mizoguchi S, Yabuhara A, Takeyama H, Matsunaga T. Magnetic separation of human podocalyxin-like protein 1 (hPCLP1)-positive cells from peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood using anti-hPCLP1 monoclonal antibody and protein A expressed on bacterial magnetic particles. Cell Struct. Funct. 2009;34:23–30. doi: 10.1247/csf.08043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen A, Laine J. Isolation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Human Cord Blood. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2007;1:2A.3.1–2A.3.7. doi: 10.1002/9780470151808.sc02a03s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara O, Tong X, Zborowski M, Chalmers JJ. Enrichment of rare cells through depletion of normal cells using density and flow-through, immunomagnetic cell separation. Exp. Hematol. 2004;32:891–904. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loutherback Loutherback K, D'Silva J, Liu L, Wu A, Austin RH, Sturm JC. Deterministic separation of cancer cells from blood at 10 mL/min. AIP Adv. 2012;2:42107. doi: 10.1063/1.4758131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski AP, Stahlschmidt U, Jérôme V, Freitag R, Müller AHE, Schmalz H. PDMAEMA-Grafted Core-Shell-Corona particles for nonviral gene delivery and magnetic cell separation. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:3081–90. doi: 10.1021/bm400703d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga T, Masayuki T, Yoshino T, Kuhara M, Takeyama H. Magnetic separation of CD14+ cells using antibody binding with protein A expressed on bacterial magnetic particles for generating dendritic cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;350:1019–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey KE, Chalmers JJ, Zborowski M. Magnetic cell separation: Characterization of Magnetophoretic Mobility. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:6868–74. doi: 10.1021/ac034315j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Y, Li K, Liu Y, Pu K, Liu B, Feng S. Herceptin functionalized polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane – conjugated oligomers - silica/iron oxide nanoparticles for tumor cell sorting and detection. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamme N, Wilhelm C. Continuous sorting of magnetic cells via on-chip free-flow magetophoresis. Lab Chip. 2006;6:974–80. doi: 10.1039/b604542a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peh GS, Lee MX, Wu FY, Toh KP, Balehosur D, Mehta JS. Optimization of human corneal endothelial cells for culture: the removal of corneal stromal fibroblast contamination using magnetic cell separation. Int. J. Biomater. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/601302. doi:10.1155/2012/601302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt ED, Huang C, Hawkins BG, Gleghorn JP, Kirby BJ. Rare Cell Capture in Microfluidic Devices. Chem Eng Sci. 2011;66:1508–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said TE, Agarwal A, Zborowski M, Grunewald S, Glander HJ, Paasch U. Utility of magnetic cell separation as a molecular sperm preparation technique. J. Androl. 2008;29:134–42. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.003632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi-Gahrouei D, Abdolahi M, Zarkesh-Esfahani SH, Laurent S, Sermeus C, Gruettner C. Fuctionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the detection and quantitative analysis of cell surface antigen. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/349408. doi: 10.1155/2013/349408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey DJ, Carr CA, Martin-Rendon E, Tyler DJ, Willmott C, Cassidy PJ, Hale SJ, Schneider JE, Tatton L, Harding SE, Radda GK, Watt S, Clarke K. Iron particles for noninvasive monitoring of bone marrow stromal cell engraftment into, and isolation of viable engrafted donor cells from, the heart. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1968–75. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumar S, Szakal AK, Tew JG. Isolation of functionally active murine follicular dendritic cells. J. Immunol. Methods. 2006;313:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talasaz AH, Powell AA, Huber DE, Berbee JG, Roh KH, Yu W, Xiao W, Davis MM, Pease RF, Mindrinos MN, Jeffrey SS, Davis RW. Isolating highly enriched populations of circulating epithelial cells and other rare cells from blood using a magnetic sweeper device. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3970–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813188106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora RH. Predicted time dependence of the switching field for magnetic materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989;63:457–460. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.63.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenstein U, Schumann A, Reif M, Link S, Toffol-Schmidt UD, Heusser P. Detection of circulating tumor cells in blood of metastatic breast cancer patients using a combination of cytokeratin and EpCAM antibodies. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino T, Hirabe H, Takahashi M, Kuhara M, Takeyama H, Matsunaga T. Magnetic cell separation using nano-sized bacterial magnetic particles with reconstructed magnetosome membrane. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008;101:470–7. doi: 10.1002/bit.21912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]