Abstract

Background

We have shown previously that cyclic stretch corresponding to that experienced by the pulmonary epithelium during normal breathing enhances nonviral gene transfer and expression in alveolar epithelial cells by increasing plasmid intracellular trafficking. Although reorganization of the microtubule and actin cytoskeletons by cyclic stretch is necessary for increased plasmid trafficking, the role of nuclear entry in this enhanced trafficking has not been elucidated.

Methods

Alveolar epithelial cells were subjected to biaxial cyclic stretch (10% change in surface area at 0.5 Hz) and assayed for RNA expression, nuclear localization and activation of key transcription factors. Stretched epithelial cells were transfected with plasmids via electroporation and exposed to inhibitors of transcription factor activation.

Results

When assayed by in situ hybridization, more plasmids were localized to the nuclei of cells that were stretched following electroporation compared to unstretched cells. Cyclic stretch also increases the nuclear localization of multiple transcription factors thought to be involved in plasmid nuclear entry, including AP1, AP2, NF-κB and NF1. Specific inhibition of the nuclear import of AP1 and/or NF-κB abolishes the enhanced plasmid nuclear localization seen with stretch.

Conclusions

Nuclear entry of plasmids is thought to be mediated by the binding of proteins that chaperone the DNA through the nuclear pore. Stretch-enhanced nuclear localization of transcription factors increases nuclear targeting of plasmids, whereas inhibition of the nuclear import of specific transcription factors abrogated stretch-enhanced plasmid nuclear localization. Taken together, these results suggest that cyclic stretch increases gene trafficking in the cytoplasm and at the nuclear envelope.

Keywords: cyclic stretch, gene therapy, electroporation, plasmid, trafficking, transcription factors

Introduction

Despite almost 20 years of study, nonviral gene transfer to the lung remains relatively inefficient [1]. To increase the efficacy of gene delivery, numerous laboratories have attempted to characterize and exploit the extracellular and intracellular pathways used during gene transfer [2]. However, most of the work has been performed in cells grown statically in tissue culture dishes, a condition that does not mimic the in vivo state where cells are constantly exposed to cyclic stretch and shear forces with each breath. We have begun to examine the effects of one of these strains on transfection efficiency in cultured cells and have shown that the intracellular trafficking of plasmids is altered with exposure to mild cyclic stretch [3,4]. The question as to how and why this occurs remains to be fully answered.

Lung epithelial cells are continuously subjected to the mechanical forces of cyclic stretch during normal ventilation. Although the over-stretching of alveoli leads to lung inflammation and injury, the mild stretching that simulates normal breathing induces a host of non-toxic cellular responses. Many investigators have shown that, in response to cyclic stretch, lung epithelial cells demonstrate a wide variety of changes, including reorganization of cytoskeletal microfilament and microtubule networks [3], increases in intracellular calcium and sodium concentrations [5–8], alterations in surfactant secretion [8], and changes in Na+/K+-ATPase activity [9]. These effects may be mediated through activation of MAP kinase activities, including JNK, ERK and p38 kinase [5,10,11]. Furthermore, transient cyclic stretch has been shown to alter the activation and/or nuclear localization of a number of transcription factors, including NF-κB and the fos and jun subunits of AP1, in smooth muscle cells and osteoblasts [12–17]. In addition to these physiological changes, we have found that DNA transfection and intracellular trafficking of plasmids is increased in cells exposed to mild cyclic stretch [4]. Although we have demonstrated that reorganization of the cytoskeleton is necessary for stretch-enhanced intracellular DNA trafficking, whether and how plasmid nuclear import is affected by stretch remains unknown.

After being internalized by a variety of transfection techniques, plasmids must move through the cytoplasm and into the nucleus of the nondividing cell for transcription to occur [18]. Previous work has found that inclusion of the 72-bp repeat sequence of the SV40 enhancer in nonviral vectors greatly increases their ability to be transported into the nucleus [19]. This sequence has been termed a DNA nuclear targeting sequence (DTS). This SV40 enhancer contains a number of binding sites for key transcription factors, including NF-κB and AP1. Transcription factors, like all nuclear proteins, contain nuclear localization signals (NLS) that are recognized by receptor proteins and imported into the nucleus. Because transcription factors as well as many other nuclear proteins are regulated by their subcellular location, a large cytoplasmic pool may exist at any one time. When a DTS-containing plasmid enters the cytoplasm, some of these factors may bind to the DTS, forming a DNA–protein complex with exposed NLS that can be recognized by the import machinery to carry the DNA into the nucleus. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies support this model [19–27]. As cyclic stretch can promote activation and/or nuclear localization of certain transcription factors, including AP1 and NF-κB, which are known to bind to the DTS, it is possible that nuclear localization of these DNA–protein complexes can be increased with stretch. In the present study, we demonstrate that mild cyclic stretch applied to cells increases activation and nuclear localization of key transcription factors in cultured alveolar epithelial cells. Furthermore, nuclear localization of plasmid DNA during stretch is profoundly affected when the nuclear localization of these transcription factors is inhibited. These results suggest that mild equibiaxial cyclic stretch not only has significant effects on transcription factor nuclear localization, but also that this localization is necessary for enhanced gene transfer.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

The plasmid pCMV-Lux-DTS expresses firefly luciferase from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate early promoter/enhancer. Plasmids were propagated in Escherichia coli and purified using Qiagen Giga-prep kits, as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA). Agarose gel electrophorectic analysis demonstrated that greater than 80% of the purified DNA was present in the supercoiled form.

Cell culture

A549 cells were purchased from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotic/antimycotic solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were plated to 80–90% confluency on pronectin coated six-well BioFlex plates (Flexcell International, McKeesport, PA, USA).

Application of cyclic stretch

Cells grown on pronectin coated six-well BioFlex plates were exposed to 10% equibiaxial cyclic stretch (Δ surface area) at 30 cycles/min (0.5 Hz) using the Flexercell baseplate with loading posts in place. Stretch was applied to the plates using the Flexercell FX 3000 (Flexcell International).

Transfection of cells

Adherent cells were transfected at 80–90% confluency using electroporation. Prior to stretching, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Plasmids (10 µg/well) were suspended in serum-free medium (1 ml/well) and added to washed cells. One 10-ms pulse of 160 V was delivered to the adherent cells using the PetriPulser electrode (BTX, San Diego, CA, USA). After electroporation, serum-containing DMEM with or without specified inhibitors were added to the cells.

Nuclear protein extraction and DNA–protein array

Nuclear proteins were extracted from stretched cells using a commercial nuclear extraction protocol adapted from Dignam et al. [28] (Panomics, Redwood City, CA, USA). Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were stored separately at −80 °C. Activation of transcription factors in the nucleus was investigated using a DNA–protein array from Panomics. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, extracted nuclear extracts were incubated with oligonucleotide probes to form DNA–protein complexes, unbound probes were washed off, and then DNA and protein were separated on an agarose gel. The separated probes were cut out of the gel and hybridized to complimentary oligonucleotides on the array, which was visualized by chemiluminescence. Each blot on the array membrane corresponded to a specific transcription factor. Signal intensities were measured by NIH Image (NIH Image, Bethesda MD, USA) and normalized to background and heat shock element (HSE).

Western blots

Ten micrograms each of fractionated nuclear and cytosolic proteins extracted from unstretched or stretched A549 cells were separated on 12.5% polyacrylamide gels by electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were used at 1 : 500 dilution and detected with horseradish peroxidase-labelled secondary antibodies using SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Blots were stripped and re-probed with anti-lamin A/C antibodies (1 : 500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA).

Electromobility shift assay (EMSA)

Gel-shift assays using biotin-labelled oligonucleotide probes were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Panomics). After extracted nuclear proteins were incubated with probes specific for a particular transcription factor, the bound oligonucleotides were separated by acrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto BiodyneB nylon membranes (Pall Life Sciences, East Hills, NY, USA) using the TransBlot SD semi-dry system (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA), and visualized by chemiluminescence. NIH Image was used to measure signal intensity, which was adjusted for background.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from stretched cells using QIAshredder and RNeasy kits (Qiagen). Extracted RNA was converted to cDNA by performing reverse transcription using 1 µg total RNA with MuLV reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed in a 20-µl reaction volume, using the DyNAmo SYBR Green qPCR Kit as described by the manufacturer (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) with the Opticon 2 DNA Engine (MJ Research, Watertown, MA, USA). Annealing temperatures were optimized for each set of primers. Standard curves were generated using seven, ten-fold dilutions of plasmid dsDNA expressing a specific transcription factor. The threshold was set manually by determining the best fit line for the quantification standards. All samples were run in duplicate and amounts were determined based on the standard curve. A melting curve analysis was preformed to ensure reaction specificity. Results were normalized to GAPDH and expressed relative to unstretched data.

In situ hybridization

After stretching, the pronectin-coated membranes and their attached, stretched cells were cut out of the six-well BioFlex plates and in situ hybridizations were performed as described previously [20], with the following exceptions. After washing with PBS, the cells were permeabilized and fixed with 100% methanol at −20 °C for 5 min followed by three washes of PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 5 min. After hybridization and washing, cells were mounted with Hoechst stain (1 µg per ml PBS). Fluorescently-labelled probes were prepared by nick translation of the plasmid as described [19] with AlexaFluor 488-5-dUTP (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Cells were visualized and images taken using a Zeiss UV LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Results

Cyclic stretch does not markedly affect gene expression of key transcription factors

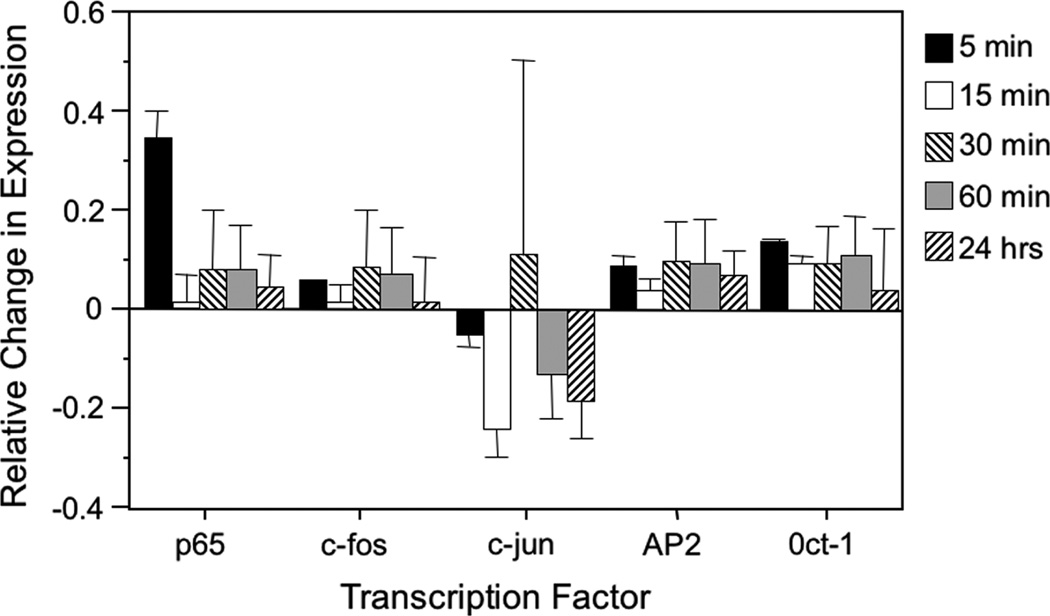

Cyclic stretch-induced changes in transcription factor activity may be mediated by increases in gene expression or by post-translational activation. To assess the effects of stretch at the transcriptional level, quantitative real-time reverse PCR was performed using mRNA extracted from A549 cells stretched for varying time intervals. Transcription factors with known binding sites on the SV40 enhancer were chosen for amplification. For NF-κB (p65 subunit), AP1 (c-fos and c-jun subunits), AP2 and Oct-1, there were no large differences in mRNA expression after normalization to GAPDH and to statically grown cells (Figure 1). Regardless of the duration of stretch, whether briefly for only 5 min or longer for 24 h, the transcription of the genes encoding these transcription factors was not significantly altered. Thus, not surprisingly, mild cyclic stretch does not appear to significantly increase expression of the transcription factors NF-κB, AP1, AP2 and Oct-1.

Figure 1.

Mild cyclic stretch does not alter transcription of select transcription factors. Total RNA was isolated immediately from A549 cells that were grown statically or stretched (10% Δ surface area, 0.5 Hz) for 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 60 min or 24 h. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR was performed to determine levels of specific mRNAs, normalized to GAPDH expression, and changes relative to unstretched cells are shown (mean ± SD). Levels of NF-κB (p65 subunit), AP1 (c-fos and c-jun subunits), AP2 and Oct-1 mRNA were measured. Results represent the data from three separate experiments and were not statistically significant by a paired Student’s t-test

Cyclic stretch alters transcription factor activation and nuclear localization in a time-dependent manner

To determine whether cyclic stretch of alveolar epithelial cells can affect the post-translational activation of certain transcription factors (i.e. nuclear localization), several approaches were used. To survey a large number of transcription factors at once, a commercially available DNA–protein dot blot array was used that allows for the simultaneous analysis and relative quantification of over 60 transcription factors on one membrane. Since the timing of stretched-induced changes in transcription factor activation and nuclear localization is unclear, nuclear extracts from unstretched cells and cells stretched for 30 min or 24 h were evaluated to detect changes that occurred early or later during the course of cyclic stretch. As expected at baseline, without any stretch, some transcription factors showed high nuclear levels, whereas others were less abundant or absent from the nuclei of A549 cells. The application of cyclic stretch for differing amounts of time affected the activation and nuclear localization of each transcription factor uniquely. To normalize each blot, we chose one factor that did not appear to change in signal intensity over time, HSE, as a standard. After normalization of the blots on the arrays to HSE, some transcription factors were more abundant in the nuclei, whereas others showed diminished activation after 30 min or 24 h of cyclic stretch (Table 1). For example, AP1, CREB, NFAT and SP1 showed increased activation and nuclear localization with either 30 min or 24 h of stretch compared to unstretched cells. By contrast, nuclear levels of CDP, GATA and MEF-1 increased with 30 min of stretch but decreased back to unstretched levels following 24 h of stretch, whereas nuclear levels of NF1, NF-E1, p53, Pax5 and SRE showed no differences at early times of stretch but increased with 24 h of treatment.

Table 1.

Transcription factor activity is altered by the duration of cyclic stretch

| 30 min | 24 h | 30 min | 24 h | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP-1 | ++ | +++ | NF-κB | NC | NC |

| AP-2 | − | + | Oct-1 | − | NC |

| ARE | ND | ND | p53 | − | ++ |

| Brn-3 | − | NC | Pax-5 | NC | ++ |

| C/EBP | ND | ND | Pbx1 | NC | +++ |

| CBF | NC | NC | Pit1 | ND | ND |

| CDP | ++ | NC | PPAR | ND | ND |

| c-Myb | NC | NC | PRE | − | + |

| CREB | ++ | + | DR5 | − | NC |

| E2F1 | NC | + | DR1 | − | NC |

| EGR | + | NC | SIE | NC | + |

| ERE | +++ | NC | SmodSBE | ND | ND |

| Ets | − | NC | Smod3/4 | +++ | ++ |

| PEA3 | − | + | Sp1 | +++ | ++ |

| FAST-1 | ND | ND | SRE | − | ++ |

| GAS | − | ++ | Stat1 | − | NC |

| GATA | +++ | NC | Stat3 | NC | + |

| GRE | − | NC | Stat4 | − | NC |

| HNF-4 | − | NC | Stat5 | ND | ND |

| IRF-1 | − | NC | Stat6 | ND | ND |

| MEF-1 | + | NC | TFIID | NC | ++ |

| MEF-2 | − | NC | TR | ++ | + |

| Myc-Max | ND | ND | DR-4 | NC | NC |

| NF-1 | NC | ++ | USF-1 | NC | NC |

| NFAT | +++ | + | DR3 | NC | NC |

| NF-E1 | − | + | HSE | NC | NC |

| NF-E2 | − | NC | MRE | − | − |

Cells were exposed to no stretch, 30 min of cyclic stretch followed by 23.5 h of static growth, or 24 h of stretch and nuclear extracts were then prepared. Levels of transcription factors were measured using the TranSignal DNA–protein array (Panomics). Extracts were prepared and analysed from three independent experiments. The resulting blots were digitized and normalized to levels of the transcription factor HSE for individual conditions. Changes in levels are relative to that seen in unstretched cells grown for 24 h. For increases in blot intensities, >50% is represented by (+), >100% by (++) and >200% by (+++). Decreases in blot intensities by more than 50% are represented by (−). NC, no change; ND, not detected.

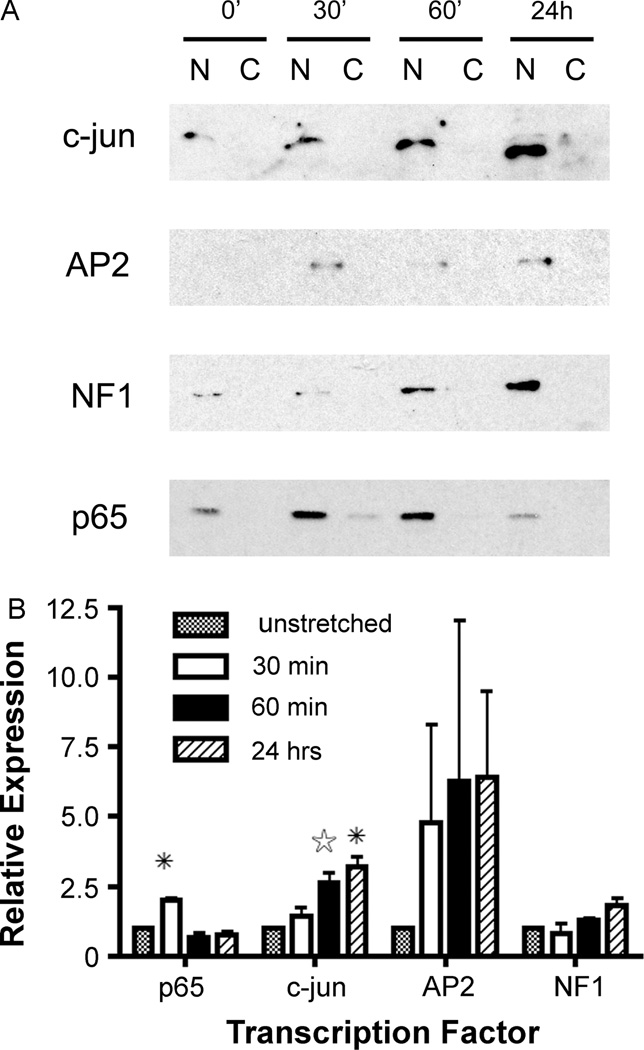

Western blots were performed to confirm the alterations in subcellular localization in response to stretch of certain key transcription factors that are known to have binding sequences on the SV40 enhancer and which likely play a role in DNA nuclear import. Cells were treated as described for the DNA protein arrays and stretched for either short (30 or 60 min) or long (24 h) periods of time, prior to isolation of nuclear extracts and analysis of protein levels by immunoblotting (Figure 2). Similar to what was seen in the arrays, nuclear c-jun (AP1) levels increased with intermediate (30 and 60 min) and long (24 h) durations of stretch. Cyclic stretch increased nuclear levels of AP2 at all times and nuclear levels of NF1 continued to rise with prolonged application of stretch. By contrast, the p65 subunit of NF-κB was increased in the nucleus with short periods of cyclic stretch and returned to baseline with longer periods of stretch.

Figure 2.

Cyclic stretch increases nuclear levels of AP1, AP2, NF1 and NF-κB. (A) Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from A549 cells exposed to 0 min, 30 min, 60 min or 24 h of stretch (10% Δ surface area, 0.5 Hz) and used for western blots. Blots were reacted with antibodies to c-jun (AP1), AP2, NF1 and p65 (NF-κB). Stripped blots were normalized with lamin A/C loading controls (not shown). N, nuclear extracts; C, cytoplasmic extracts. (B) Immunoblots were digitized and normalized to the levels of lamin A/C for individual conditions. Changes in levels are relative to that seen in unstretched cells grown for 24 h. Experiments were repeated at least two times for each transcription factor. *P < 0.05. ✰P = 0.055 by paired Student t-test

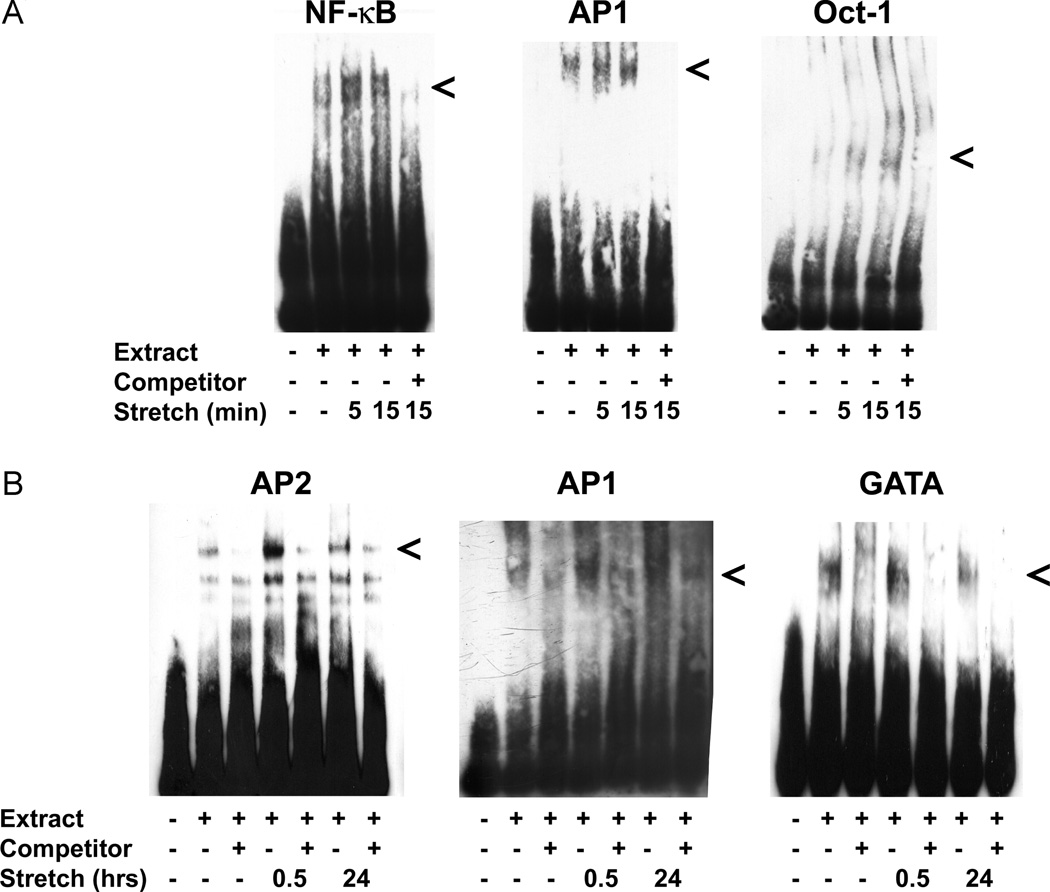

The activation of these key transcription factors that likely play a role in the nuclear targeting of plasmids during gene transfer was furthered analysed using EMSAs on nuclear extracts from A549 cells. Time points were chosen to evaluate early events (5 and 15 min) as well as later events (30 min and 24 h). As seen in Figure 3, activation and nuclear localization of NF-κB, GATA and Oct-1 occurs early, whereas AP1 and AP2 activation occurs later with mild cyclic stretch. These results confirm and extend the array and western blot results and support our hypothesis that the increased activation and nuclear localization of key transcription factors may aid in the increased nuclear uptake of transfected plasmid in stretched cells.

Figure 3.

Activation of key transcription factors occurs after brief and prolonged exposure to cyclic stretch. (A) NF-κB, AP1 and Oct-1 are activated in briefly stretched cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared from cells stretched for 0, 5 or 15 min (10% Δ surface area, 0.5 Hz) and used for EMSA using biotin-labelled probes for specific consensus binding sites in the absence or presence of 66-fold excess of unlabelled probe as competitor. (B) AP1, AP2 and GATA are activated in cells stretched for prolonged periods. EMSAs were performed using nuclear extracts prepared from cells stretched for 0, 0.5 or 24 h as in (A)

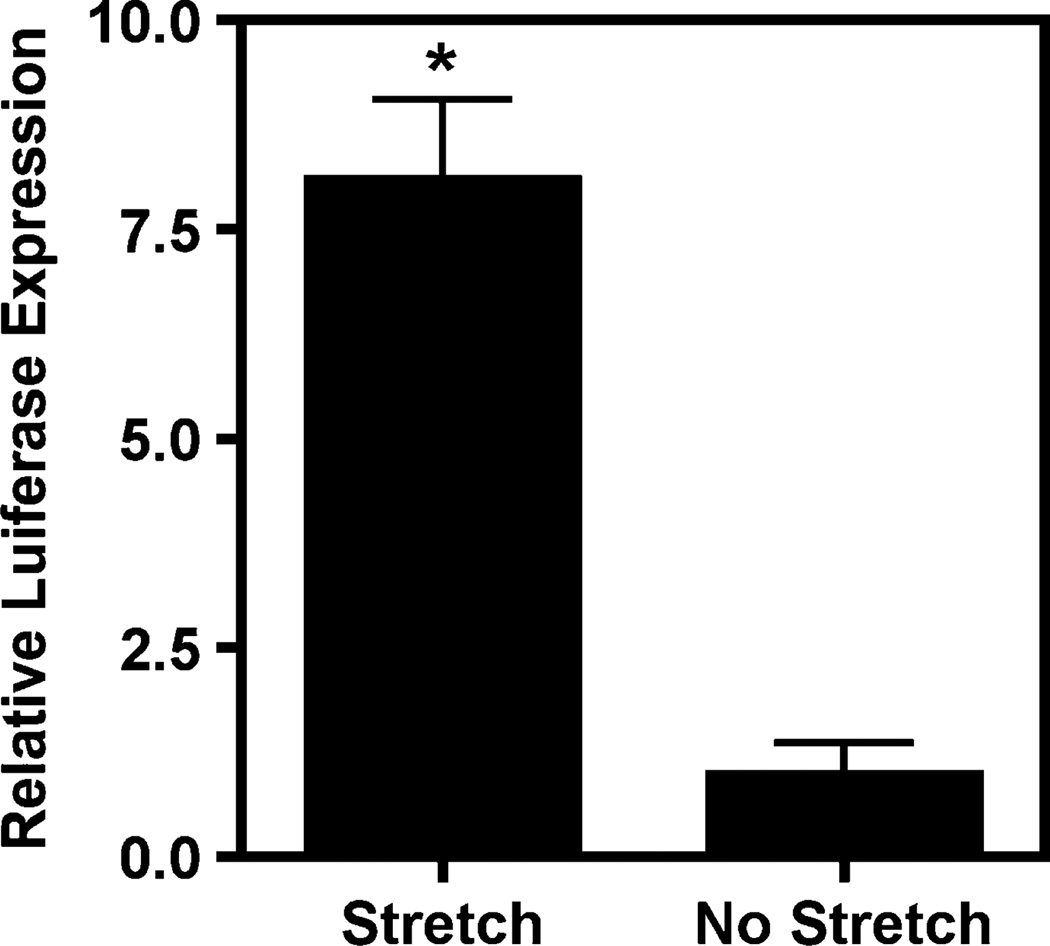

Cyclic stretch increases nuclear localization of plasmid DNA

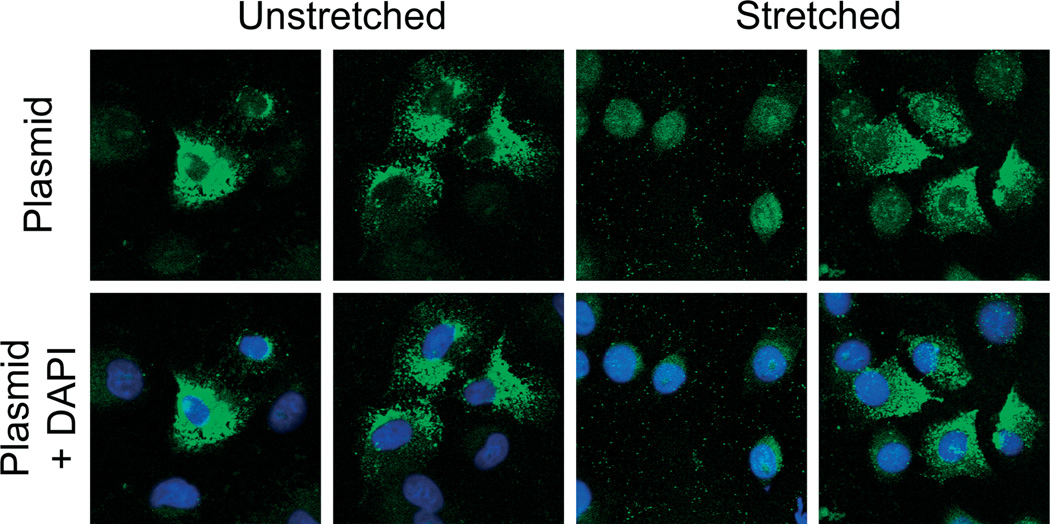

Previous work has shown that cyclic stretch applied after electroporation or liposome-mediated transfection of plasmids containing the SV40 enhancer increases luciferase expression compared to unstretched cells (Figure 4) [3,4]. Although this has been interpreted to be due to increased cytoplasmic and nuclear trafficking of the plasmids in stretched cells, direct analysis of the DNA has not been shown. To determine whether cyclic stretch can increase intracellular trafficking of plasmids into the nucleus, cells were electroporated with plasmid, grown with or without mild cyclic stretch and, 6 h later, the subcellular location of the plasmids was evaluated by in situ hybridization. The majority of the detected plasmid in statically grown cells appeared to be cytoplasmic and was relatively evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of the cells (Figure 5). However, many of the cells clearly showed small amounts of plasmid in the nucleus, usually indicating that at least some of the transfected plasmids do gain entry into the nuclei by this time. Indeed, when gene expression was measured in stretched or static cells 6 h after electroporation, cells grown statically did show gene expression, although it was almost eight-fold lower than that seen in stretched cells (Figure 4). Thus, it is likely that this low level nuclear import seen by in situ hybridization may account for this gene expression. By contrast, when cells were stretched for 6 h following electroporation, a large percentage of the cells showed predominantly nuclear localized plasmid (Figure 5). A smaller percentage of the cells had varying amounts of nuclear-localized compared to cytoplasmic levels of plasmid, somewhat similar to that seen in unstretched cells. These results suggest that application of cyclic stretch does indeed increase the amount of plasmid that reaches and enters the nucleus in cells.

Figure 4.

Cyclic stretch enhances transgene expression following transfection. A549 cells were electroporated with pCMV-Lux-DTS and grown statically or with 10% equibiaxial cyclic stretch at 0.5 Hz for 6 h at which point luciferase activity was measured. Mean ± SD luciferase activities (RLU/mg cell protein) were normalized to transfected cells grown statically. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times. *P < 0.01 by a paired Student’s t-test

Figure 5.

Cyclic stretch enhances nuclear entry of plasmid DNA. A549 cells were electroporated with pCMV-Lux-DTS and grown statically or with 10% equibiaxial cyclic stretch at 0.5 Hz for 6 h. In situ hybridization was performed using AlexaFluor 488-5-dUTP-labelled probe (green) to detect the transfected plasmids and cells were also stained Hoechst stain (blue) to visualize nuclei. Images are representative of cells on pronectin membranes from experiments repeated at least two times

Inhibition of activation of key transcription factors abrogates stretch-mediated nuclear localization of DTS-containing DNA

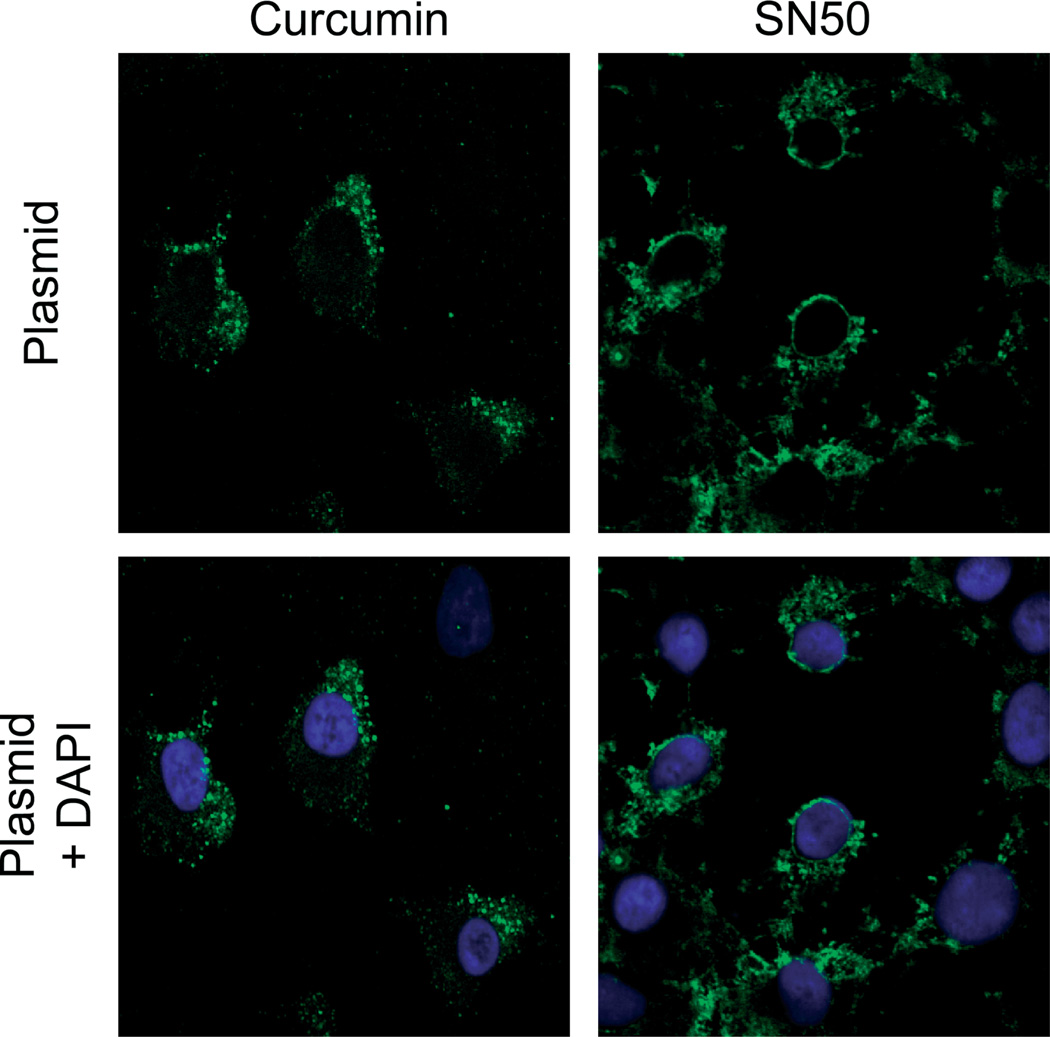

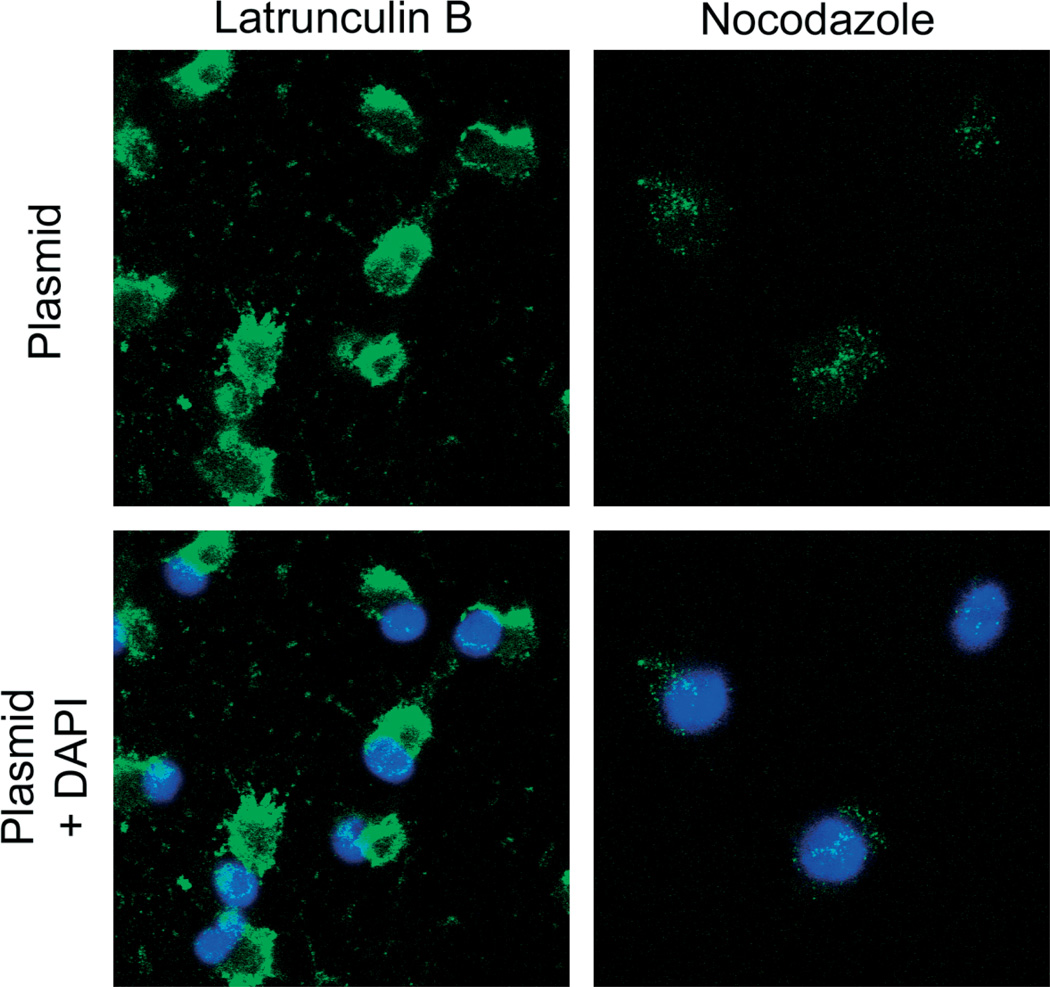

As all the data collected to date from our laboratory and others suggests that plasmids enter the nucleus of the nondividing cell using the nuclear localization signals of specifically bound transcription factors [19–24], it is reasonable to conclude that the increased nuclear localization of a number of transcription factors caused by cyclic stretch is at least one mechanism by which cyclic stretch increases gene transfer and transfection efficiency. To determine whether the nuclear localization of at least some of these transcription factors is needed for nuclear targeting of plasmids, we employed several inhibitors that have been shown to prevent the nuclear accumulation of either NF-κB and/or AP1 (Figure 6). Although cyclic stretch increases transcription factor and plasmid DNA nuclear localization, inhibition of the activation and nuclear localization of both NF-κB and AP1 by curcumin abolished the ability of cyclic stretch to facilitate the nuclear import of SV40-DTScontaining plasmids (Figure 6). However, curcumin is also known to cause alterations in cytoskeletal organization [29,30]. Thus, the effect of curcumin on cytoskeletal organization and cell shape may influence stretch-enhanced trafficking of plasmid DNA into the nucleus because both of these factors have been shown to affect expression of electroporated plasmids [3,31]. To exclude this possibility, inhibitors of microtubule and actin polymerization were used. Neither nocodazole, nor latrunculin B abrogated nuclear translocation of DNA with stretch (Figure 7), suggesting that the inhibition of DNA nuclear targeting was due to inhibition of transcription factor mobilization. In support of this, SN50, a specific inhibitor of NF-κB activation that has not been shown to induce any cytoskeletal reorganization [32], also prevents the nuclear entry of plasmids containing the SV40 enhancer (Figure 6). Taken together, these results suggest that the increased activation of key transcription factors, including NF-κB and AP1, induced by mild cyclic stretch is necessary to facilitate increased plasmid nuclear import and that the prevention of the nuclear entry of NF-κB and AP1 abolishes this effect of cyclic stretch.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of AP1 and/or NF-κB nuclear import inhibits nuclear entry of plasmids. Cells were preincubated with curcumin (100 µM) or SN50 (18 µM) for 1 h prior to electroporation with pCMV-Lux-DTS. Cells were stretched (10% Δ surface area, 0.5 Hz) for 6 h in the presence of the same inhibitor immediately following electroporation. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue) and plasmid DNA was visualized by in situ hybridization using an AlexaFluor 488-5-dUTP-labelled probe (green). Representative cells from experiments repeated at least two times are shown

Figure 7.

Neither latrunculin B, nor nocodazole alter DNA nuclear import in stretched cells. Cells were preincubated with latrunculin B (2.5 µM) or nocodazole (6.6 µM) for 1 h and then electroporated with pCMV-Lux-DTS and stretched for 6 h in the presence the same inhibitor. In situ hybridization was then performed to detect transfected DNA (green) and nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Representative cells from experiments repeated at least two times are shown

Discussion

Lung alveolar epithelial cells normally function to maintain the alveolar capillary barrier, alveolar fluid absorption and surfactant synthesis. Many investigators have shown that, in response to cyclic stretch, lung epithelial cells demonstrate changes in various signaling pathways [33]. Consistent with these findings, we have demonstrated that mild cyclic stretch (10% change in basement membrane surface area) affects activation of a number of transcription factors but has little effect on expression of these factors at the transcriptional level. Furthermore, this mild cyclic stretch dramatically stimulates nuclear localization of plasmid DNA containing the SV40 enhancer, which encodes binding sites for many of these stretch-activated transcription factors. Specific inhibition of NF-κB and AP1 activation/nuclear localization abrogates this stretch-enhanced DNA nuclear targeting. Taken together, these results are consistent with a model in which stretch-enhanced gene transfer is in part mediated by increased activation of transcription factors by stretch, which in turn bind to plasmids and mediate greater DNA nuclear localization and expression.

Similar to that observed in a variety of other cell types [12–15,34], we have shown, using several methods, that cyclic stretch in A549 cells also alters the activation and subcellular localization of a variety of transcription factors. As expected, mild cyclic stretch, which simulates tidal breathing [35–37], does not appear to significantly alter transcription factor expression. Other investigators have demonstrated in a variety of tissues that regulation of transcription factor activity by stretch occurs via changes in activation [12,13,38,39]. Indeed, large-scale changes in the subcellular localization of a number of transcription factors were identified using a novel DNA–protein array and confirmed by western blot and EMSA. Verification using standard techniques was necessary since new assays usually have technical limitations, which, in the case of this DNA–protein array, lies in the difficulty of normalization of dot intensities between membranes. The manufacturer recommends selecting a transcription factor that does not appear to alter with the varying conditions or normalization against the ‘standard’ dots along the periphery of the blot. Unfortunately, with the former method, selecting a ‘static’ protein for normalization is difficult because even ‘housekeeping’ gene activities can change with stimuli [40]. In this case, no transcription factor appeared to be unchanged regardless of the duration of stretch, and so HSE was chosen, given that all experiments were performed at the same stable temperature and prior microarray data showed no changes (D. A. Dean, unpublished data). With the latter method, there are obvious problems with heterogeneity in intensities of the ‘standard’ dots along the periphery. Perhaps the best use of this DNA–protein array technology may be to provide a ‘snap-shot’ of activity of a large number of transcription factors at a particular point in time, rather than for comparison with differing time or treatment intervals.

We demonstrated that cyclic stretch activates a number of transcription factors in A549 cells and that the timing of this event varies with the specific transcription factor. It is not surprising that certain transcription factors should be activated rapidly in response to certain stimuli, whereas others may respond later after prolonged stimulus. Copland and Post [41] have shown that, in fetal lung epithelial cells, 17% (surface area) cyclic stretch of only 30 min significantly increases nuclear localization of NF-κB, which in turn directly alters expression of other important factors such as HSP70 and MIP-2. Similarly, in human airway smooth muscle cells, Kumar et al. [42] demonstrated that AP1 activation in response to cyclic stretch occurs in a time-dependent fashion with maximal activation around 1 h and that inhibition of AP1 with decoy oligonucleotides abolished AP1-dependent, stretch-induced increases in interleukin-1 levels. Our current finding that most transcription factor activation occurs by 30 min of stretch corresponds to the previous report of 30 min of cyclic stretch resulting in the same level of reporter gene expression as 24 h of stretch [4]. Thus, the timing of stretch-mediated activation not only varies with the individual transcription factor but will consequently also affect DNA expression.

The current model for plasmid nuclear localization in nondividing cells proposes that transcription factors present in the cytoplasm bind to specific sequences on plasmids to generate a DNA–protein complex that can interact, through the NLSs of the transcription factors, with the NLS import machinery, resulting in nuclear entry of the complex. Thus, if more transcription factors are present in the cytoplasm to form DNA–protein complexes or if the nuclear localization of these transcription factors is stimulated, increased nuclear targeting of delivered plasmids should also be seen. Since cyclic stretch activates key transcription factors (including NF-κB, AP1, AP2 and NF1) and promotes their nuclear localization, this could account for the increased DNA nuclear trafficking seen following stretch of transfected cells [3,4,43]. Indeed, the timing of transcription factor activation by stretch also coincides with that seen for increased transfection efficiency: activation of NF-κB, AP1, AP2 and NF1 occurred within 30 min of application of stretch, the same amount of time cyclic stretch was needed for maximal effects on gene transfer and expression following transfection [4]. Furthermore, in support of this model, Mesika et al. [44] have demonstrated that cells transfected with plasmids containing NF-κB-binding sequences showed increased plasmid nuclear localization and transgene expression when the cells were stimulated with tumor necrosis factor-α, a known activator of NF-κB.

Although it has been shown that inhibition of general NLS-mediated protein nuclear import with agents that occlude the NPC, such as wheat germ agglutinin and antibodies against nucleoporins, also inhibits the nuclear localization of plasmids [20,45–48], the effects of specific inhibition of the nuclear import of proteins thought to be involved in plasmid nuclear entry has not been well studied. Mesika et al. [22] showed that deletion of the NLS of p50 prevents nuclear entry of DNA containing multiple NF-κB-binding sites. In the present study, in situ hybridization clearly shows the markedly enhanced nuclear localization of SV40 enhancer-containing plasmids with cyclic stretch, corroborating the prior findings of increased gene transfer and expression following stretch. Nuclear exclusion of the plasmid by SN50, which blocks recognition by importin β of the NLS on NF-κB/Rel family members, highlights the importance of NF-κB activation in trafficking of plasmids containing NF-κB binding sites. Although similar results were obtained with curcumin, which blocks the nuclear import of both NF-κB and AP1, the results are complicated by the destabilizing effects of the drug on microtubules, intermediate filaments, and actin [29,30]. However, treatment of cells with latrunculin B and nocodazole to destabilize the actin and tubulin networks did not alter the increased nuclear import of plasmids seen with cyclic stretch, confirming our previous studies [3], and suggesting that the effects of curcumin were indeed mediated by NF-κB and AP1 trafficking.

The contrasting effects of mild cyclic stretch which simulates normal tidal breathing and high level cyclic stretch that represents the over-stretching of the lung, has been the focus of much research. As compared to smaller changes, equibiaxial cyclic stretch with large deformational changes (50% versus 12% Δ surface area) results in drastic increases in cell death [35,37]. In a septic rat model, differences in alveolar cell death are further accentuated bymild versus high deformation cyclic stretch [49]. Other detrimental effects of high deformation cyclic stretch include loss of alveolar epithelial barrier integrity, alteration in cell signaling pathways, and induction of cytokine release [50–53]. Thus, in the present study, we use mild cyclic stretch of 10% Δ surface area to avoid the deleterious effects of high deformation stretch and to study the effects on transcription factors and DNA nuclear import under conditions that more closely mimic normal tidal ventilation.

Stretching of cells is known to affect mechanotransduction and alter the cytoskeletal structure. Changes in the cytoskeleton have been shown to affect cytoplasmic trafficking of large molecules, including plasmid DNA [3,54]. Mild cyclic stretch causes large-scale depolymerization of the microtubule network and causes stress fibers and microfilaments to become shorter and move to the periphery of the cell [3]. Additionally, stabilization of the microtubule and microfilament networks with taxol and jasplakinolide, respectively, abrogates the stretch-induced increases in reporter gene expression. By contrast, destabilization of the networks with nocodazole and latrunculin B neither diminishes the stretch-mediated effects on gene expression, nor increases gene expression in static cells. In concert with the results from the present study, all of these findings suggest that stretch-enhanced gene expression requires both cytoskeletal reorganization to enable DNA to move towards the nucleus and increases in transcription factor nuclear localization to permit nuclear entry of the plasmids.

The importance of investigating stretch-mediated changes in gene transfer to the lungs is clear given that, after almost 20 years of attempts at pulmonary gene therapy, there have been no unqualified successes, largely due to poor levels of gene transfer. The lungs are continuously subjected to the mechanical forces of stretch, as well as shear and compression, as we breathe. Furthermore, these forces can be exquisitely controlled by mechanical ventilation. Based on our previous and current results in pulmonary epithelial grown in culture, it is very possible that application of cyclic stretch to the lung using low tidal volume ventilation may also improve gene delivery in vivo. Ongoing experiments will determine whether this non-toxic method also improves intracellular trafficking of DNA for effective gene therapy in the lung.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank R. Chris Geiger, Joshua Gasiorowski, Erin Vaughan and Teng-Leong Chew for insightful discussions and technical advice. This work was supported in part by grants HL71643 (D.A.D.) and HL78145 (A.P.L.) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the NIH.

References

- 1.Rosenecker J, Huth S, Rudolph C. Gene therapy for cystic fibrosis lung disease: current status and future perspectives. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2006;8:439–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss D. Delivery of gene transfer vectors to lung: obstacles and the role of adjunct techniques for airway administration. Mol Ther. 2002;6:148–152. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geiger RC, Taylor W, Glucksberg MR, et al. Cyclic stretch-induced reorganization of the cytoskeleton and its role in enhanced gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2006;13:725–731. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor W, Gokay KE, Capaccio C, et al. Effects of cyclic stretch on gene transfer in alveolar epithelial cells. Mol Ther. 2003;7:542–549. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correa-Meyer E, Pesce L, Guerrero C, et al. Cyclic stretch activates ERK1/2 via G proteins and EGFR in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:L883–L891. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00203.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felix JA, Woodruff ML, Dirksen ER. Stretch increases inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate concentration in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;14:296–301. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.3.8845181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wirtz HR, Dobbs LG. Calcium mobilization and exocytosis after one mechanical stretch of lung epithelial cells. Science. 1990;250:1266–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.2173861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashino Y, Ying X, Dobbs LG, et al. [Ca(2+)](i) oscillations regulate type II cell exocytosis in the pulmonary alveolus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L5–L13. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.1.L5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waters CM, Ridge KM, Sunio G, et al. Mechanical stretching of alveolar epithelial cells increases Na(+)-K(+)- ATPase activity. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:715–721. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li LF, Ouyang B, Choukroun G, et al. Stretch-induced IL-8 depends on c-Jun NH2-terminal and nuclear factor-kappaBinducing kinases. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L464–L475. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00031.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinn D, Tager A, Joseph PM, et al. Stretch-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and interleukin-8 production in type II alveolar cells. Chest. 1999;116:89S–90S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.89s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granet C, Boutahar N, Vico L, et al. MAPK and SRC-kinases control EGR-1 and NF-kappa B inductions by changes in mechanical environment in osteoblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:622–631. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaqour B, Howard PS, Richards CF, et al. Mechanical stretch induces platelet-activating factor receptor gene expression through the NF-kappaB transcription factor. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1345–1355. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JM, Adam RM, Peters CA, et al. AP-1 mediates stretchinduced expression of HB-EGF in bladder smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C294–C301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.2.C294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peake MA, Cooling LM, Magnay JL, et al. Selected contribution: regulatory pathways involved in mechanical induction of cfos gene expression in bone cells. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:2498–2507. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.6.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamura K, Chen YE, Lopez-Ilasaca M, et al. Molecular mechanism of fibronectin gene activation by cyclic stretch in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34619–34627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tremblay L, Valenza F, Ribeiro SP, et al. Injurious ventilatory strategies increase cytokines and c-fos m-RNA expression in an isolated rat lung model. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:944–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI119259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaughan EE, DeGiulio JV, Dean DA. Intracellular trafficking of plasmids for gene therapy: mechanisms of cytoplasmic movement and nuclear import. Curr Gene Ther. 2006;6:671–681. doi: 10.2174/156652306779010688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean DA, Dean BS, Muller S, et al. Sequence requirements for plasmid nuclear entry. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:713–722. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dean DA. Import of plasmid DNA into the nucleus is sequence specific. Exp Cell Res. 1997;230:293–302. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesika A, Grigoreva I, Zohar M, et al. A regulated, NFkappaB-assisted import of plasmid DNA into mammalian cell nuclei. Mol Ther. 2001;3:653–657. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mesika A, Kiss V, Brumfeld V, et al. Enhanced intracellular mobility and nuclear accumulation of DNA plasmids associated with a karyophilic protein. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:200–208. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vacik J, Dean BS, Zimmer WE, et al. Cell-specific nuclear import of plasmid DNA. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1006–1014. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson GL, Dean BS, Wang G, et al. Nuclear import of plasmid DNA in digitonin-permeabilized cells requires both cytoplasmic factors and specific DNA sequences. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22025–22032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, MacLaughlin FC, Fewell JG, et al. Muscle-specific enhancement of gene expression by incorporation of the SV40 enhancer in the expression plasmid. Gene Ther. 2001;8:494–497. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young JL, Benoit JN, Dean DA. Effect of a DNA nuclear targeting sequence on gene transfer and expression of plasmids in the intact vasculature. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1465–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blomberg P, Eskandarpour M, Xia S, et al. Electroporation in combination with a plasmid vector containing SV40 enhancer elements results in increased and persistent gene expression in mouse muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:505–510. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dignam JD. Preparation of extracts from higher eukaryotes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:194–203. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82017-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohashi Y, Tsuchiya Y, Koizumi K, et al. Prevention of intrahepatic metastasis by curcumin in an orthotopic implantation model. Oncology. 2003;65:250–258. doi: 10.1159/000074478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holy JM. Curcumin disrupts mitotic spindle structure and induces micronucleation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mutat Res. 2002;518:71–84. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(02)00076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaughan EE, Dean DA. Intracellular trafficking of plasmids during transfection is mediated by microtubules. Mol Ther. 2006;13:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Y-Z, Yao S, Veach RA, et al. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-kB by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization signal. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14255–14258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waters CM, Sporn PHS, Liu M, et al. Cellular biomechanics in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L503–L509. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00141.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen HT, Adam RM, Bride SH, et al. Cyclic stretch activates p38 SAPK2-, ErbB2-, and AT1-dependent signaling in bladder smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1155–C1167. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.4.C1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tschumperlin DJ, Margulies AS. Equibiaxial deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1998;275:L1173–L1183. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tschumperlin DJ, Margulies AS. Alveolar epithelial surface area-volume relationship in isolated rat lungs. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:2026–2033. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.6.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tschumperlin DJ, Oswari J, Margulies AS. Deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells. Effect of frequency, duration, and amplitude. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:357–362. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9807003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Fabry B, Schiffrin EL, et al. Twisting integrin receptors increases endothelin-1 gene expression in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1475–C1484. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.6.C1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Beqaj S, Kemp P, et al. Stretch-induced alternative splicing of serum response factor promotes bronchial myogenesis and is defective in lung hypoplasia. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1321–1330. doi: 10.1172/JCI8893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tricarico C, Pinzani P, Bianchi S, et al. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction: normalization to rRNA or single housekeeping genes is inappropriate for human tissue biopsies. Anal Biochem. 2002;309:293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Copland IB, Post M. Stretch-activated signaling pathways responsible for early response gene expression in fetal lung epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:133–143. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar A, Knox AJ, Boriek AM. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein and activator protein-1 transcription factors regulate the expression of interleukin-8 through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in response to mechanical stretch of human airway smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18868–18876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dean DA. Improving gene delivery and expression of GFP by cyclic stretch. In: Spector DL, Goldman RD, editors. Live Cell Imaging: A Laboratory Manuel. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2004. pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mesika A, Grigoreva I, Zohar M, et al. A regulated, NFkappaB-assisted import of plasmid DNA into mammalian cell nuclei. Mol Ther. 2001;3:653–657. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson GL, Dean DA. Nuclear import of plasmid DNA in permeabilized cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9S:188A. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dowty ME, Williams P, Zhang G, et al. Plasmid DNA entry into postmitotic nuclei of primary rat myotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4572–4576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sebestyén MG, Ludtke JL, Bassik MC, et al. DNA vector chemistry: the covalent attachment of signal peptides to plasmid DNA. Nature Biotech. 1998;16:80–85. doi: 10.1038/nbt0198-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagstrom JE, Ludtke JJ, Bassik MC, et al. Nuclear import of DNA in digitonin-permeabilized cells. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2323–2331. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.18.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levine GK, Deutschman CS, Helfaer MA, et al. Sepsis-induced lung injury in rats increases alveolar epithelial vulnerability to stretch. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1746–1751. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218813.77367.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cavanaugh KJ, Cohen TS, Margulies SS. Stretch increases alveolar epithelial permeability to uncharged micromolecules. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1179–C1188. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00355.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cavanaugh KJ, Jr, Margulies SS. Measurement of stretch-induced loss of alveolar epithelial barrier integrity with a novel in vitro method. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C1801–C1808. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00341.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamamoto H, Teramoto H, Uetani K, et al. Cyclic stretch upregulates interleukin-8 and transforming growth factor-beta1 production through a protein kinase C-dependent pathway in alveolar epithelial cells. Respirology. 2002;7:103–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2002.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vlahakis NE, Schroeder MA, Limper AH, et al. Stretch induces cytokine release by alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L167–L173. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.1.L167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dauty E, Verkman AS. Actin cytoskeleton as the principal determinant of size-dependent DNA mobility in cytoplasm: a new barrier for non-viral gene delivery. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7823–7828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]