Abstract

Anopheles darlingi, one of the main malaria vectors in the Neotropics, is widely distributed in French Guiana, where malaria remains a major public-health problem. Elucidation of the relationships between the population dynamics of An. darlingi and local environmental factors would appear to be an essential factor in the epidemiology of human malaria in French Guiana and the design of effective vector-control strategies. In a recent investigation, longitudinal entomological surveys were carried out for 2–4 years in one village in each of three distinct endemic areas of French Guiana. Anopheles darlingi was always the anopheline mosquito that was most frequently caught on human bait, although its relative abundance (as a proportion of all the anophelines collected) and human biting rate (in bites/person-year) differed with the study site. Seasonality in the abundance of human-landing An. darlingi (with peaks at the end of the rainy season) was observed in only two of the three study sites. Just three An. darlingi were found positive for Plasmodium (either P. falciparum or P. vivax) circumsporozoite protein, giving entomological inoculation rates of 0·0–8·7 infectious bites/person-year. Curiously, no infected An. darlingi were collected in the village with the highest incidence of human malaria. Relationships between malaria incidence, An. darlingi densities, rainfall and water levels in the nearest rivers were found to be variable and apparently dependent on land-cover specificities that reflected the diversity and availability of habitats suitable for the development and reproduction of An. darlingi.

Human malaria remains a major public-health problem in French Guiana, with a mean of about 4000 cases (representing 2% of the total population) reported in each of the last 10 years (Carme et al., 2009). Although Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax are equally common (with <3% of the malaria cases attributable to P. malariae), the predominant Plasmodium species varies regionally. The coastal area, where 75% of the inhabitants of French Guiana live, is characterised by a large number of imported cases and a few foci of autochthonous transmission. The country’s main malaria-endemic areas are located in the inland forest, especially along the main rivers and some of their tributaries (i.e. in the Mana and Maroni basins in the west and the Approuagues and Oyapock basins in the east).

Over the last few years, although P. falciparum was once widely distributed throughout French Guiana, the incidence of P. falciparum malaria has decreased in some western areas, particularly in the Maroni valley (Carme et al., 2009). In contrast, the incidence of P. vivax malaria in eastern areas, particularly that recorded in the Oyapock valley, has increased, to the point where up to 50% of children in some of the communities develop the disease each year (Carme, 2005; Carme et al., 2005). Anopheles darlingi, one of the most efficient malarial vectors in the Neotropics, is widely distributed in French Guiana. For more than 50 years, it has been described as the major malarial vector in the country, because of its strong anthropophilic behaviour, high prevalences of infection and the high densities of aggressive females observed during emerging malaria outbreaks (Floch and Abonnenc, 1951; Floch, 1955). Although other potential vectors, such as An. aquasalis, An. brasiliensis, An. nuneztovari and An. oswaldoi, are also sometimes present at high densities in the human environment in French Guiana, their involvement in the malarial transmission that occurs in the country has not yet been confirmed (Mouchet et al., 1989).

The larval stages of An. darlingi may be found in a variety of natural habitats, including creeks, strips of flooded forest, river edges and river-bed pools (the size and number of which fluctuate depending on rainfall and river levels). The species, although naturally a forest mosquito, has colonised human-altered landscapes such as deforested areas, where human activity provides suitable larval habitats in the form of road ditches, vehicle ruts, mining pits etc.

Previous research on An. darlingi bionomics and malarial transmission dynamics in French Guiana has focused on Surinamese and French villages along the Maroni river — because of the high incidence of malaria historically reported in such communities (Hudson, 1984; Rozendaal, 1992; Girod et al., 2008; Fouque et al., 2010; Hiwat et al., 2010). The results have allowed the risks of malarial transmission along the Maroni river to be estimated but most of the contributory factors, such as the bionomics and behavioural characteristics of the An. darlingi in the human environment and the relationships between mosquito densities, climatology, hydrology, land cover and malaria incidence, have yet to be elucidated. Moreover, the lack of entomological data from other malaria-endemic areas of French Guiana limits the implementation of effective vector-control operations that are adapted to local conditions.

The aim of the present, longitudinal survey, which ran from January 2003 to December 2006, was to explore the malarial vectors and associated transmission dynamics around three villages in the Amazonian forest of French Guiana. The study villages lie in three distinct endemic regions. The relationships between the entomological observations and environmental factors (such as climatology, hydrology and land cover) that may affect the malaria situation in the three study areas were explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Sites

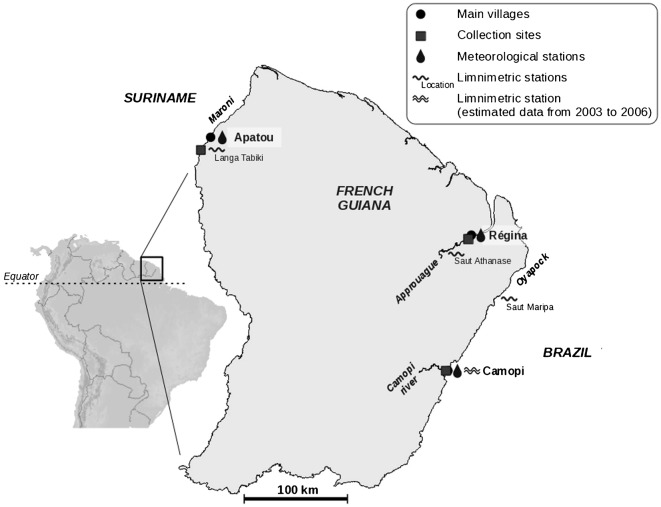

Longitudinal entomological studies were implemented in the vicinity of each of three Amazonian villages in French Guiana: Camopi, Apatou and Régina (Fig. 1). The three study sites all represent more-or-less anthropogenic landscapes but differ in terms of agricultural practices and population size and composition.

Figure 1.

A map showing the locations of the Camopi, Apatou and Régina mosquito-collection sites and the meteorological and limnimetric stations close to them.

Camopi is an Amerindian village located in the middle-Oyapock region, in the south–eastern part of French Guiana, near the Brazilian border. The ‘village’ is actually a collection of more than 20 hamlets that cover a 15-km2 area along the Oyapock River and one of its main tributaries, the Camopi River, and together hold about 1000 people. Field collections of mosquitoes were made in the largest hamlet and in dispersed hamlets located along the two rivers. Although most of the villagers still live in open huts made of wood with roofs of steel sheet or palm leaves, more modern concrete houses are progressively replacing such huts, particularly in the largest hamlet, which has the ‘village’’s only health centre. The villagers practise subsistence-level slash-and-burn agriculture, gradually increasing the area under cultivation.

The district of Apatou is located in the lower-Maroni region, in the north–west of French Guiana, close to the Surinamese border. Its 5500 Marron inhabitants live either in the village of Apatou (which hold’s the district’s only health centre) or in several hamlets on the French-Guianan side of the Maroni River. Field collections of mosquitoes were made in the hamlets of Midenangalanti and Bois Martin. Midenangalanti, which, at the start of the study, had a population of about 70, lies 15-km upstream of Apatou village and consists of approximately 15 traditional houses on the river bank. Bois Martin lies 5-km upstream of Midenangalanti and, at the start of the study, had 20 (non-permanent residents) who lived in traditional houses on the river bank. The inhabitants of Midenangalanti and Bois Martin also practise subsistence-level slash-and-burn agriculture. Both hamlets are surrounded by primary Amazonian forest although this is broken by cultivated areas and patches of secondary forest.

The village of Régina, which also has a health centre, lies on the right bank of the Approuagues River, in north–eastern French Guiana and, at the start of the study, had 750 inhabitants who were a mixture of Creoles, Amerindians and Brazilian immigrants. Mosquitoes were collected in a place named ‘Village Inéri’, which is actually only a hamlet about 1·5 km from the centre of Régina village and about 1 km from the Approuagues River. When the present study began, about 100 people lived in ‘Village Inéri’, in a mixture of traditional and modern houses surrounded by forest and flooded savannah. Although subsistence-level slash-and-burn agriculture is practised around the hamlet, there is also more intensive agriculture (with larger plots, shorter fallow periods, and the use of agricultural fertilizers and pesticides) for the production of vegetables and citrus fruits as cash crops.

The three study sites are all surrounded by Amazonian rainforest and have similar climates, being hot (mean temperature = 27°C) and humid (mean relative humidity = 80%) all year round. Four seasons are recognised in French Guiana: a long rainy season (mid-April–mid-July), a long dry season (mid-July–November), a short rainy season (December–January) and a short dry season (February–mid-April).

Entomology

Mosquitoes were collected outdoors as they landed on local residents who were employed by the Pasteur Institute of French Guiana and carefully supervised by an entomologist. At each study site, collections were made, on one night or two consecutive nights in every month or 2 months, by four collectors, two of whom worked from 18·30 to 00·30 hours while the other two worked from 00·30 to 06·30 hours.

Mosquitoes landing on the exposed lower legs of the collectors were caught with mouth aspirators and transferred to collecting pots that were labelled with the place and time of collection. Morphology and the relevant keys for the Amazonian region (Faran and Linthicum, 1981; Linthicum, 1988) were used to identify all the mosquitoes caught to genus and the anopheline mosquitoes to species. As they were identified, the mosquitoes were transferred (one/vial) to numbered vials with desiccant. They were then transported to the Pasteur Institute in Cayenne, where they were held at −20°C until they could be processed further. Subsequently, the head and thorax of each female anopheline mosquito were tested, using an ELISA, for the circumsporozoite proteins (CSP) of P. falciparum, P. vivax (VK210 and VK247 variant epitopes) and P. malariae (Wirtz et al., 1987, 1992).

Human biting rates (HBR) were estimated as the number of female anopheline bites/person-night while entomological inoculation rates (EIR; presented as the number of infectious bites/person-night) were calculated as the products of the HBR and the proportions of the tested mosquitoes found to be positive for any CSP.

Malaria Data

Malaria is a disease under epidemiological surveillance in French Guiana. Once a week, the staff in health posts, health centres and public and private biomedical laboratories report all the confirmed cases of malaria that they have observed in the previous 7 days, to the health authority. A suspected case of malaria is considered confirmed if the case’s body temperature exceeds 38°C or the case is found febrile within 48 h of being found bloodsmear-positive for malarial parasites or positive for Plasmodium-specific protein in a rapid diagnostic test (i.e. the OptiMAL® test; Diamed AG, Cressier sur Morat, Switzerland).

For the present study, the incidences of malaria reported weekly (and routinely) by the health centres in the three study areas were transferred into Excel (Microsoft) databases. More detailed data, on individual cases of malaria, were obtained from the health centres of Camopi and Régina. These data allowed the cases resulting from therapeutic failure in P. falciparum or P. malariae infection (indicated by the return of fever within a week of treatment) or from P. vivax relapse (indicated by two episodes of P. vivax malaria within a 90-day period; Hanf et al., 2009) to be excluded. For Apatou, however, the only malariometric data available were those routinely held in the territorial database for health surveillance, and these were insufficient to exclude cases resulting from therapeutic failure or P. vivax relapse.

For the data analyses, the populations of the three study areas were considered to be stable (and not to decline or increase) over the study period.

Environmental Data

rainfall and heights of river water

The relevant rainfall records were provided by the French meteorological services in French Guiana, which collects data daily from automatic stations in the villages of Camopi, Apatou and Régina (Fig. 1). Similarly, daily data on local river levels were provided by the national department of environmental services and came from hydrometric stations at Saut Maripa (on the Oyapock River, 90 km downstream from Camopi), Saut Athanase (on the Approuagues River, 25 km upstream of Régina), and Langatabiki (on the Maroni River, 20 km upstream of Apatou) (Fig. 1). Although Saut Maripa lies at a considerable distance from Camopi, river levels at these two locations have been measured simultaneously in the past and these simultaneous measurements allowed the river levels at Camopi for the period of interest (2003–2006) to be estimated from those recorded at Saut Maripa.

The records of daily rainfall and river levels were converted, using the R® software package (www.r-project.org), into weekly cumulated rainfall and weekly maximum river levels. The weekly data were then stored in an Excel database.

land cover and landscape characterisation

Characterisation of the land cover around the three study sites was based on colour images taken by the SPOT 5 satellite at a 10-m spatial resolution and provided by the SEAS-Guyane project (www.seas-guyane.org). The main images of Camopi, Apatou and Régina were acquired on 20 August 2006, 10 August 2006 and 26 September 2006, respectively. An additional image of the site of Régina, taken on the 21 September 2006, was used to provide the values that were missing from the main image of this site because of cloud cover.

A semi-supervised classification, combining an unsupervised pixel-based clustering algorithm implemented in GRASS GIS® software (http://grass.osgeo.org/) and the intervention of an operator guided by field knowledge and photo-interpretation expertise, was performed in order to characterise the land cover. The methodology was the same for the three study sites. Air photographs at 50-cm spatial resolution, taken in 2006 by the French Institut Geographique National (Saint-Mandé, France) and held in the institute’s BD ORTHO® database, were visually interpreted to label the classes identified with the satellite images and to validate the classification qualitatively.

Landscape characterisation was performed by extracting land-cover features within a discoidal buffer around each collection site. As the flight range of An. darlingi has rarely been explored (Deane et al., 1948; Charlwood and Alecrim, 1989; Achee et al., 2005), various buffer radii (200, 500, 1000, 2000, 5000 and 7000 m) were used, the largest value representing the maximum flight distance ever reported for An. darlingi (Charlwood and Alecrim, 1989).

Variables included in the landscape characterisation were the percentage of each land cover class, the length of river banks (Maroni, Oyapock/Camopi, and Approuagues) and the degree of landscape division (Jaeger, 2000).

Since the mosquito collections for Camopi and Apatou were each made in several hamlets, landscape in Camopi and Apatou was characterised as weighted averages (of the landscape-feature values extracted for the separate collection points), with the numbers of collection nights used as weights.

Statistical Analysis of Relationship Between Entomological, Environmental and Parasitological Data

Associations between the cumulated rainfall and maximum river levels, numbers of malaria cases and An. darlingi HBR were investigated be calculating Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficients, using the Stata® software package (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

The relationships between the HBR for An. darlingi observed in a mosquito collection and cumulative rainfall or maximum river level recorded between 2 and 4 weeks earlier were explored. Similarly, the relationships between the HBR for An. darlingi observed in a mosquito collection and malaria incidence recorded between 2 and 4 weeks after that mosquito collection were also investigated. The lag periods that were tested were based on the generation time of An. darlingi and estimates of the mean time between Plasmodium infection of anopheline mosquitoes and the development of the first clinical symptoms in people bitten by those infected mosquitoes (Service and Townson, 2002; Warrell, 2002).

A P-value of <0·05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference or correlation.

RESULTS

Mosquito Collections and Description of the Anopheline Fauna

Between January 2003 and December 2006, 282 nights of mosquito collection yielded 4444 mosquitoes, of which 3123 (70·3%) were anopheline. Anopheles darlingi, with 2947 specimens collected, represented 94·4% of the anopheline fauna, while An. nuneztovari was the second most common species in the collections (Table 1).

Table 1. The numbers of female mosquitoes collected on human bait in the Camopi, Apatou and Régina study sites in 2003–2006.

| No. collected and (% of anophelines collected) in: | |||

| Type of mosquito | Camopi | Apatou | Régina |

| Culicidae | 1023 | 1358 | 2063 |

| Anophelinae | 215 (100·0) | 1272 (100·0) | 1636 (100·0) |

| Anopheles darlingi | 148 (68·8) | 1167 (91·7) | 1632 (99·8) |

| An. nuneztovari | 39 (18·1) | 101 (7·9) | 4 (0·2) |

| An. oswaldoi | 13 (6·0) | 4 (0·4) | 0 |

| An. intermedius | 5 (2·4) | 0 | 0 |

| An. mediopunctatus | 2 (0·9) | 0 | 0 |

| An. ininii | 2 (0·9) | 0 | 0 |

| An. argyritarsis | 1 (0·5) | 0 | 0 |

| An. maculipes | 1 (0·5) | 0 | 0 |

| Anopheles sp.* | 4 (1·9) | 0 | 0 |

*Four specimens of anopheline mosquito were too damaged to identify to species.

In Camopi, collections were made every month from January 2003 to December 2004 (except in April 2003 and July 2004) and then every 2 months until December 2006. Eight anopheline species were identified in this study area, An. darlingi, An. nuneztovari and An. oswaldoi representing 68·8%, 18·1% and 6·0% of the anophelines caught, respectively. Overall, 112 nights of collection yielded 148 female An. darlingi, giving corresponding HBR of 1·3 bites/person-night or 482·7 bites/person-year.

Close to Apatou, collections were made monthly from January 2005 to December 2006 (except in November 2005 and 2006) in Midenangalanti, and from January to December 2006 (except in January 2006 and November 2006) in Bois Martin. Only three anopheline species were identified, with An. darlingi and An. nuneztovari representing 91·7% and 7·9% of the anophelines caught, respectively. Overall, 128 nights of collection close to Apatou yielded 1167 female An. darlingi, giving corresponding HBR of 9·1 bites/person-night or 3330·1 bites/person-year.

In the ‘Village Inéri’, close to Régina, collections were made every 2 months between January 2005 and December 2006, with An. darlingi again the predominant anopheline species collected. Overall, 42 nights of collection in this study area yielded 1632 female An. darlingi, giving corresponding HBR of 38·9 bites/person-night or 14,192·6 bites/person-year.

Seasonal Abundance of Anopheles darlingi and Other Anopheline Species

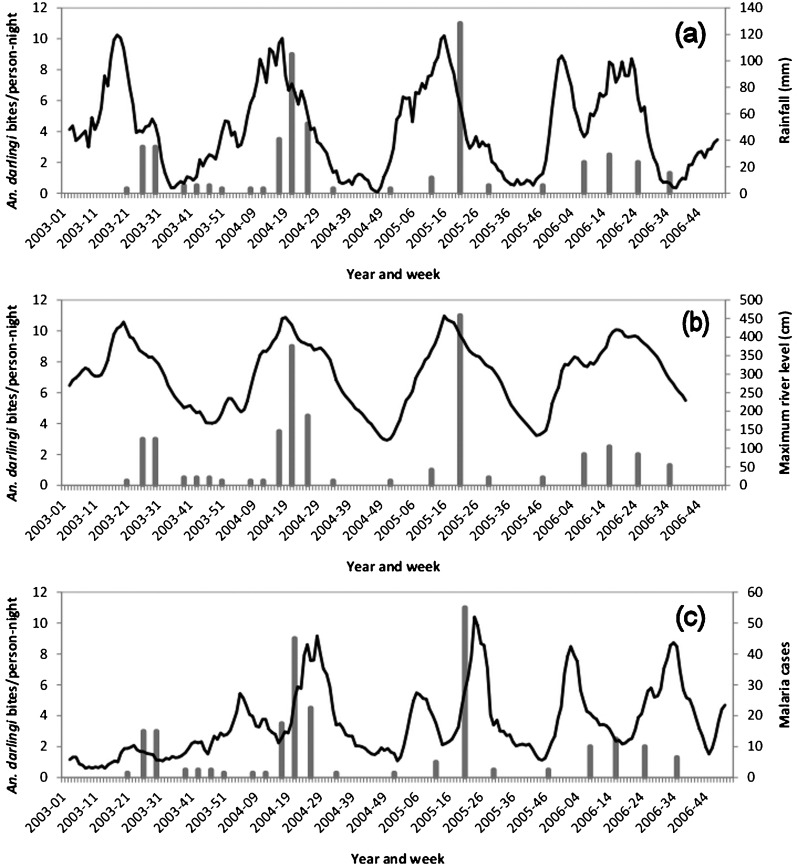

In the study site of Camopi, the abundance of adult (human-landing) An. darlingi peaked during the long rainy season, from April to July, with the two highest HBR — 9·0 and 11·0 bites/person-night — recorded in May 2004 and May 2005, respectively. During the rest of the year, An. darlingi HBR remained at low levels (<2·0 bites/person-night), with no An. darlingi being collected in some months (Fig. 2). Although only 39 female An. nuneztovari were collected at this site, over 4 years of the study, the An. nuneztovari HBR reached 10·5 bites/person-night (in May 2005).

Figure 2.

In these three graphs, the bars show Anopheles darlingi human biting rates at the Camopi study site while the lines show rainfall at Camopi (a), maximum river levels at Saut Maripa (b), and the number of malaria cases presenting at the Camopi health centre (c).

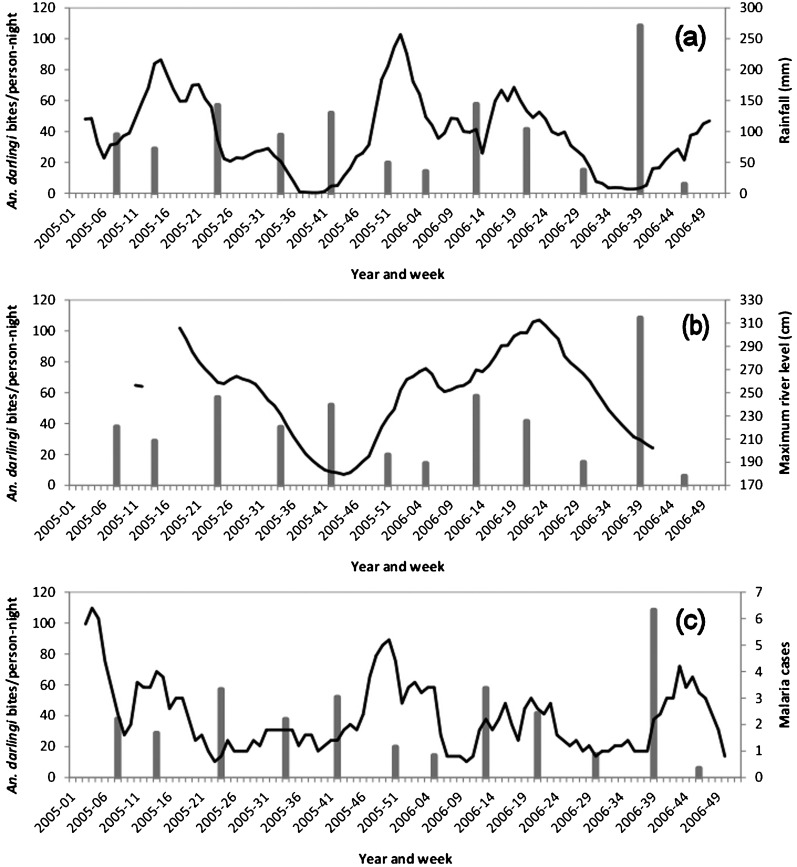

In Midenangalanti and Bois Martin, the abundance of adult (human-landing) An. darlingi also peaked during the long rainy season, with the highest HBR (78·5 bites/person-night) recorded in June 2005. During the rest of the year, An. darlingi HBR at this site remained below 15·0 bites/person-night (Fig. 3). A total of 101 An. nuneztovari was collected during the 2 years of the study, with the HBR for this species peaking, at 8·3 bites/person-night, in December 2006.

Figure 3.

In these three graphs, the bars show Anopheles darlingi human biting rates in Midenangalanti and Bois Martin while the lines show rainfall at Apatou (a), maximum river levels at Langatabiki (b), and the number of malaria cases presenting at the Apatou health centre (c).

Close to Régina, in the ‘Village Inéri’, adult (human-landing) An. darlingi were present all year round, with no clear seasonal peak in their abundance (Fig. 4), although the HBR for this species varied from 108·5 bites/person-night (in September 2006) to just 6·0 bites/person-night (in November 2006).

Figure 4.

In these three graphs, the bars show Anopheles darlingi human biting rates in ‘Village Inéri’ (Régina) while the lines show rainfall at Régina (a), maximum river levels at Saut Athanase (b), and the number of malaria cases presenting at the Régina health centre (c).

Anopheles darlingi Entomological Inoculation Rates

Although all 3123 of the female anopheline mosquitoes collected were processed by ELISA to see if they contained P. falciparum, P. vivax and/or P. malariae CSP, only three — two An. darlingi from close to Apatou (both positive for P. falciparum) and one An. darlingi from Régina (positive for P. vivax) — gave a positive result.

The annual circumsporozoite indices for An. darlingi were 0·17% in the study site close to Apatou and 0·06% in the Régina sites, giving corresponding EIR of 5·7 and 8·7 infectious bites/person-year, respectively.

Seasonal Variations in Malaria Incidence

Between 2003 and 2006, 3604 malaria cases were confirmed at the health centre in Camopi, with annual means of 365 cases of P. falciparum malaria and 528 cases of P. vivax malaria. Malaria incidences showed seasonality (Fig. 2), with a peak in January–February (i.e. at the end of the short rainy season) and another in July–August (at the end of the long rainy season).

At the health centre in Apatou, 171 malaria cases were confirmed in 2005–2006 (109 in 2005 and 62 in 2006), with 146, three and 22 of them attributed to P. falciparum, P. vivax and P. malariae, respectively. As in Camopi, malaria incidence showed two seasonal peaks and, again as in Camopi, these occurred in January–February and July–August (Fig. 3).

In the health centre of Régina, 237 malaria cases were reported in 2005–2006, with almost all of them attributed to P. falciparum (49 cases in 2005 and 47 in 2006) or P. vivax (86 cases in 2005 and 50 in 2006). At this health centre, however, no clear-cut seasonal variation in malaria incidence was observed during the study period (Fig. 4).

Seasonal Variations in Rainfall and River Level

In the study site of Camopi, mean annual rainfall over the study period was 2545·4 mm, the wettest months being March, April and May. The nearby Oyapock River fell to its lowest levels in November–December and reached its highest levels in April–May (Fig. 2).

At Apatou, mean annual rainfall over the study period was very similar (2748·2 mm) but the wettest months were January and May. The water levels in the nearby Maroni River were relatively low in November–January and peaked in May (Fig. 3).

Compared with the other two study sites, that at Régina was much wetter (mean annual rainfall = 4914·6 mm), with particularly heavy rainfall in December–January and April–May (Fig. 4). On the nearby Approuagues River, water levels were lowest in October–November and highest in April–June (Fig. 4).

Correlations between Rainfall, River Level, Malaria Cases and An. darlingi Abundance

At the Camopi study site, significant correlations were observed between HBR and cumulative rainfall (recorded 2–4 weeks earlier), maximum river levels (recorded 2–4 weeks earlier) and malaria incidence (recorded 2–4 weeks later) (see Figure 2 and Table 2).

Table 2. Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficients for the relationships between Anopheles darlingi human biting rates (HBR) and cumulative rainfall (2–4 weeks earlier), maximum water level in the closest river (2–4 weeks earlier), and the incidence of human malaria recorded (2–4 weeks later) in the local health centre.

| Coefficient and (corresponding P-value) for relationship between HBR and: | |||

| Study site | Rainfall | River level | Malaria incidence |

| Camopi | 0·48 (0·005) | 0·58 (<0·001) | 0·46 (<0·01) |

| Apatou | 0·28 (0·2) | 0·60 (0·003) | −0·00 (1·0) |

| Régina | −0·04 (0·9) | 0·08 (0·8) | 0·43 (0·2) |

At the Apatou site, however, HBR was only found to be significantly correlated with the maximum river levels recorded 2–4 weeks earlier (see Figure 3 and Table 2) while at the Régina site no significant correlations were detected (see Figure 4 and Table 2).

Land Cover

Overall, nine classes of land cover were identified. The percentage of each study site represented by each of the classes is shown, as a function of buffer size, in Figure 5.

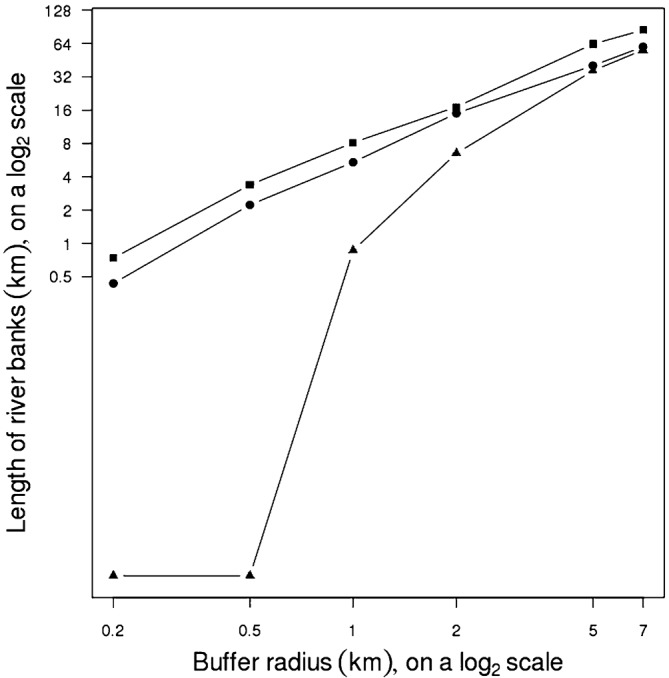

Figure 5.

Percentage of each land-cover class, as a function of buffer size, at the study sites of Camopi (▪), Régina (▴) and Apatou (•).

At a large scale (i.e. with buffers with radii of 5 or 7 km), the three study sites differed in the proportion of their area covered by secondary/humid valley-floor forest (a class of land cover that appeared most common at the Régina site).

With the radii of the buffer zones set at 200 or 500 m, more differences between the study sites became apparent. No deep water body was included in the buffer zone at the Régina site, for example, because the nearest river lay outside of the zone. At the same site, the use of a buffer zone with a radius of 200 m also excluded any shallow and/or shady water bodies (the swamp associated with the ‘Village Inéri’ being more than 200 m from the community).

With buffer zones measuring at least 500 m in radius, shallow and/or shady water bodies occupied similar percentages of the land cover at the three sites but differed in nature; they corresponded to river banks at the Camopi and Apatou sites and to swamp at the Régina (‘Village Inéri’) site. Since the ‘Village Inéri’ swamp could be identified in satellite images acquired during the dry season (on the 21 and 26 September 2006), it is assumed to be a permanently flooded area.

With the smaller buffer zones, the Régina site was found to have higher proportions of secondary/humid valley-floor forest, grassland/low vegetation and shrubs than the other two study sites. ‘Secondary/humid valley-floor forest’ may include both anthropogenic areas (secondary growth) and non-anthropogenic areas (humid valley-floor forest), which give similar radiometric responses.

The lengths of the river banks included in the buffer zones are shown Figure 6. The Camopi site held the longest stretches of riverbank (with both the Oyapock and Camopi Rivers contributing). The Régina site had a relatively weak interaction with the Approuagues River, especially when the radius of the buffer zone was <1 km (partially because of the distance between the centre of the site and the river).

Figure 6.

Lengths of river bank within the Camopi (▪), Régina (▴) and Apatou (•) study sites, as a function of buffer size.

The degree of landscape division of the non-flooded areas was greatest at the Régina site, whatever the buffer size, mainly because of the anthropogenic surfaces.

DISCUSSION

Variability in Anopheles darlingi Abundance and Implications for Malaria Transmission

The present results represent the first information available on the mosquito fauna of the lower-Maroni, lower-Approuagues and middle-Oyapock areas of French Guiana. Almost all of the mosquitoes collected on humans at night in the study villages in these inland malaria-endemic areas were anopheline. Most were An. darlingi, a species that has predominated among the mosquitoes collected in other peridomestic areas of French Guiana (Floch, 1955; Pajot et al., 1977; Claustre et al., 2001; Girod et al., 2008) and one that appears to be highly anthropophilic throughout the Amazon region (Tadei et al., 1998; Magris et al., 2007; present results). In the present study, as seen in some earlier investigations (Panday, 1977; Rozendaal, 1987), a few other anopheline species, in particular An. nuneztovari, were sometimes collected on humans in large numbers. The three study sites varied in terms of the mean HBR for An. darlingi (approximately one bite/person-night in the village of Camopi, nine bites/person-night in the Apatou study site, and 39 bites/person-night in the Régina study site) and in whether such HBR showed marked seasonality (Camopi and Apatou) or not (Régina). Such seasonal and geographical variation in the HBR of anophelines has already been described in the Amazon region (Da Silva-Vasconcelos et al., 2002; Gil et al., 2003).

All the female anophelines collected were checked for Plasmodium CSP but only a few specimens of An. darlingi (collected in the study sites of Apatou and Régina) were found to be positive. Even though it remains possible that one or more of the rarer species of Anopheles is involved in malarial transmission, it seems likely that the parasites causing human malaria in the Apatou and Régina study sites are predominantly transmitted by An. darlingi in peridomestic environments. Although this may also be true for the village of Camopi (relatively few anopheline mosquitoes were collected in this study site and none was found CSP-positive), an alternative possibility is that, in Camopi, most malarial transmission does not occur in peridomestic environments (where mosquitoes were collected during the present study) but in the forest around the village, via the bites of sylvatic anopheline species. In some other areas of the Amazon region, even where An. darlingi occurs, other Anopheles species have been found responsible for the transmission of malarial parasites to humans (Panday, 1977; Povoa et al., 2001; Da Silva-Vasconcelos et al., 2002).

Relationships between Human Biting Rates and Rainfall and River Levels

Statistical analysis revealed (1) a significant correlation between An. darlingi HBR and the rainfall that fell a few weeks earlier (at Camopi but not at Apatou or Régina) and (2) a significant correlation between An. darlingi HBR and the maximum levels recorded, a few weeks earlier, in the nearest river (at Camopi and Apatou but not at the Régina site). The seasonal variation seen in the HBR at the ‘Village Inéri’, close to Régina, did not reflect fluctuations in local rainfall or river levels.

Positive correlations between An. darlingi densities and rainfall and/or river levels have been observed previously, in the Maroni valley and elsewhere in the Amazon region (Hudson, 1984; Rozendaal, 1987; Monteiro de Barros and Honorio, 2007; Girod et al., 2008; Hiwat et al., 2010). Situations showing no correlation between An. darlingi densities and rainfall and river levels, as observed in the present study at the Régina site, have, however, also been described before (Gil et al., 2003; Magris et al., 2007; Moreno et al., 2007). Such geographical variation underlines the fact that, even at subregional level, the characteristics of the local landscape need to be explored if the relationships between climate, An. darlingi population dynamics and malarial transmission are to be understood.

Human Biting Rates and Land Cover

In the present study, classification of satellite images allowed nine classes of land cover to be identified. Although these are, to a certain extent, similar to the ones identified by Vittor et al. (2006, 2009), using images from the Landsat-7 thematic mapper (at 30-m spatial resolution), the process of classification used in the present study allowed deep water (corresponding to the river stream) and shallow and/or shady water bodies (corresponding to shady rivers, parts of rivers along shady banks, or wetlands composed of shallow water surfaces with sparse vegetation) to be distinguished.

Only the river levels near to Camopi and Apatou (and not those near to Régina) appeared to be correlated with An. darlingi densities a few weeks later. Land cover at the Camopi and Apatou appeared quite similar, with high percentages of deep water (corresponding to the Oyapock/Camopi and Maroni river streams, respectively) and forest. The Oyapock/Camopi and Maroni Rivers presumably play an important role in the emergence of productive breeding places for An. darlingi at the end of the long rainy season, when the forested zones are flooded because of the high river levels. It is unclear why HBR were found to be correlated with rainfall only in the Camopi study site but it seems likely that only at this site were many An. darlingi breeding places created directly by rainfall, perhaps as puddles in the dense forest around the village. The two hamlets of Midenangalanti and Bois Martin, enclosed between the Maroni River and hills, present different forest features to those in the Camopi study site. Further investigations should be performed to evaluate the numbers of breeding places directly associated with rainfall in the Camopi and Apatou areas.

At the Régina study site, the absence of a correlation between HBR and either rainfall or river level may also be linked to land-cover and land-use specificities. There are permanently flooded areas near this site (swamps and humid-valley floors) that, presumably, provide many perennial breeding places for An. darlingi whether rainfall is heavy or light. This site also lies relatively far from the nearest river and within 1 km of only short stretches of river bank. In addition, it is close enough to the Atlantic Ocean for the nearest river water to be brackish at high tide, inhibiting the breeding of An. darlingi on the river banks.

The Régina site was the one showing the greatest variation in land cover, mainly because of the relatively intense and varied agriculture human activity. Large densities of An. darlingi often develop once human activity has caused ‘deterioration’ in the natural landscape (Tadei et al., 1998; Vittor et al., 2006, 2009) and this — and the permanently flooded areas — may explain why An. darlingi HBR were found to be so high at the Régina site.

Human Biting Rates and Malaria Incidence

The correlations observed between (peridomestic) HBR and malaria incidences — which only reached statistical significance in Camopi village — are difficult to interpret. Malaria incidence in Camopi showed two seasonal peaks, one in July–August (when An. darlingi HBR were relatively high) and another in January–February (when, curiously, An. darlingi HBR were relatively low). It is possible that the An. darlingi in peridomestic areas of Camopi village maintain malaria transmission in January–February even when present at low densities. It is also possible that most transmission in Camopi at this time of the year (and in the Apatou and Régina study sites at most or all times of the year) does not occur in peridomestic environments (where mosquitoes were collected and HBR estimated in the present study) but in the forest. The seasonal fluctuations seen in malaria incidence in the Apatou and Régina study sites do not reflect the HBR of peridomestic An. darlingi recorded a few weeks earlier. This observation, and similar observations made elsewhere in the Amazon region (Camargo et al., 1996; Moreno et al., 2007), particularly in the Maroni valley (Girod et al., 2008; Hiwat et al., 2010), indicate that An. darlingi density is not the most important factor affecting malaria-transmission risk in some places. In Venezuela, however, Magris et al. (2007) detected a strong correlation between An. darlingi densities and malaria incidence, similar to that seen, in the present study, in Camopi village.

As suggested by Moreno et al. (2007) and Fouque et al. (2010), it seems probable that the longevity of An. darlingi populations may play an important role in malaria-transmission dynamics in certain situations. In some areas, however, the presence and vector role of sylvatic species of anopheline mosquito could explain the epidemiology of malaria. Pajot et al. (1978) showed that most of the human malaria in Trois-Sauts, an Amerindian village upstream of Camopi but still in the middle-Oyapock region, could be transmitted by An. neivai, a sylvatic species that breeds in water trapped in bromeliads. Curiously, Molez (1999) described two Amerindian myths related to the malaria transmission, one associating transmission with the rivers and the other associating transmission with the forest. If there is considerable transmission occurring in the forests, this may explain how, in the present investigation, the Camopi study site could have the highest incidences of malaria despite having the lowest HBR for peridomestic An. darlingi.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the official and traditional authorities of the ‘Village Inéri’, Midenangalanti, Bois Martin and Camopi village, for their warm welcome, and, especially, the mosquito collectors, for their commitment to the present study. They are also grateful to C. Grenier and M. Joubert, who are in charge of managing health centres and health posts in French Guiana. Access to the data on malaria incidence was facilitated by V. Ardillon and C. Flamand (who are in charge of epidemiological surveillance in French Guiana). The former head of the medical entomology unit of the Pasteur Institute in Cayenne (P. Rabarison) is thanked for his support, and, finally, the help of S. Chaney with editing the authors’ English is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- Achee NL, Grieco JP, Andre RG, Rejmankova E, Roberts DR.(2005)A mark–release–recapture study using a novel portable hut design to define the flight behavior of Anopheles darlingi in Belize, Central America. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 21366–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo LMA, dal Colletto GMD, Ferreira MU, Gurgel Sde M, Escobar AL, Marques A, Krieger H, Camargo EP, da Silva LH.(1996)Hypoendemic malaria in Rondonia (Brazil, western Amazon region): seasonal variation and risk groups in an urban locality. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 5532–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carme B.(2005)Substantial increase of malaria in inland areas of eastern French Guiana. Tropical Medicine and International Health 10154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carme B, Lecat J, Lefebvre P.(2005)Le paludisme dans le foyer de l’Oyapock (Guyane): incidence des accès palustres chez les amérindiens de Camopi. Médecine Tropicale 65149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carme B, Ardillon V, Girod R, Grenier C, Joubert M, Djossou F, Ravachol F.(2009)Situation épidémiologique du paludisme en Guyane. Médecine Tropicale 6919–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlwood JD, Alecrim WA.(1989)Capture–recapture studies with the South American malaria vector Anopheles darlingi. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 83569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claustre J, Venturin C, Nadiré M, Fauran P.(2001)Vecteurs du paludisme en Guyane française: étude dans un foyer épidémique proche de Cayenne (1989–1998). Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique 94353–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva-Vasconcelos A, Kato MYN, Mourao EN, de Souza RTL, Lacerda RN, Sibajev A, Tsouris P, Povoa MM, Momem H, Rosa-Freitas MG.(2002)Biting indices, host-seeking activity and natural infections rates of anopheline species in Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazil from 1996 to 1998. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 97151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane LM, Causey OR, Keane MP.(1948)Notas sobre a distribuicao e a biologia dos anofelinos das regioes Nordestina a Amazonica do Brasil. Revista do Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública 1827–966. [Google Scholar]

- Faran ME, Linthicum KJ.(1981)A handbook of the Amazonian species of Anopheles (Nyssorhynchus) (Diptera: Culicidae). Mosquito Systematics 131–81. [Google Scholar]

- Floch H.(1955)La lutte antipaludique en Guyane française. L’anophélisme. Rivista di Malariologia 2457–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floch H, Abonnenc E.(1951)Anophèles de la Guyane française. Archives de l’Institut Pasteur de la Guyane et du Territoire de l’Inini 2361–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fouque F, Gaborit P, Carinci R, Issaly J, Girod R.(2010)Annual variations in the number of malaria cases related to two different patterns of Anopheles darlingi transmission potential in the Maroni area of French Guiana. Malaria Journal 980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil SLH, Alves FA, Zieler H, Salcedo JMV, Durlacher RR, Cunha RPA, Tada MS, Camargo LMA, Camargo EP, Pereira da Silva LH.(2003)Seasonal malaria transmission and variation of anopheline density in two distinct endemic areas in Brazilian Amazonia. Journal of Medical Entomology 40636–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girod R, Gaborit P, Carinci R, Issaly J, Fouque F.(2008)Anopheles darlingi bionomics and transmission of Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malariae in Amerindian villages of the upper-Maroni Amazonian forest, French Guiana. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 103702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanf M, Stefani A, Basurko C, Nacher M, Carme B.(2009)Determination of the Plasmodium vivax relapse pattern in Camopi, French Guiana. Malaria Journal 8278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiwat H, Issaly J, Gaborit P, Somai A, Samjhawan A, Sardjoe P, Soekhoe T, Girod R.(2010)Behavioral heterogeneity of Anopheles darlingi (Diptera: Culicidae) and malaria transmission dynamics along the Maroni river (Suriname, French Guiana). Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 104207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JE.(1984)Anopheles darlingi in the Suriname rain forest. Bulletin of Entomological Research 74129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger JAG.(2000)Landscape division, spitting index, and effective mesh size: new measures of landscape fragmentation. Landscape Ecology 15115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Linthicum KJ.(1988)A revision of the Argyritarsis section of the subgenus Nyssorhynchus of Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae). Mosquito Systematics 2098–271. [Google Scholar]

- Magris M, Rubio-Palis Y, Menares C, Villegas L.(2007)Vector bionomics and malaria transmission in the Upper Orinoco River, southern Venezuela. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 102303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molez JF.(1999)Les mythes représentant la transmission palustre chez les indiens d’Amazonie et leurs rapports avec deux modes de transmission rencontrés en forêt. Cahiers de Santé 9157–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro de Barros FS, Honorio NA.(2007)Man biting rate seasonal variation of malaria vectors in Roraima, Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 102299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JE, Rubio-Palis Y, Páez E, Pérez E, Sánchez V.(2007)Abundance, biting behavior and parous rate of anopheline mosquito species in relation to malaria incidence in gold-mining areas of southern Venezuela. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 21339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchet J, Nadire-Galliot M, Poman JP, Lepelletier L, Claustre J, Bellony S.(1989)Le paludisme en Guyane. Les caractéristiques des différents foyers et la lutte antipaludique. Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique 82393–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajot FX, Le Pont F, Molez JF, Degallier N.(1977)Agressivité d’Anopheles (Nyssorhynchus) darlingi Root, 1926 (Diptera: culicidae) en Guyane française. Cahiers de l’ORSTOM, Série Entomologie Médicale et Parasitologie 1515–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pajot FX, Molez JF, Le Pont F.(1978)Anophèles et paludisme sur le haut Oyapock (Guyane française). Cahiers de l’ORSTOM, Série Entomologie Médicale et Parasitologie 16105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Panday RS.(1977)Anopheles nuneztovari and malaria transmission in Suriname. Mosquito News 37728–737. [Google Scholar]

- Povoa MM, Wirtz RA, Lacerda RNL, Miles MA, Warhurst D.(2001)Malaria vectors in the municipality of Serra do Navio, state of Amapa, Amazon region, Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 96179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozendaal JA.(1987)Observations on the biology and behaviour of anophelines in the Suriname rainforest with special reference to Anopheles darlingi Root. Cahiers de l’ORSTOM, Série Entomologie Médicale et Parasitologie 2533–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rozendaal JA.(1992)Relations between Anopheles darlingi breeding habitats, rainfall, river level and malaria transmission rates in the rain forest of Suriname. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 616–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Service MW, Townson H.(2002)The Anopheles vector Essential Malariology 4th Edneds Warrell D A, Gilles H M.ed pp. 59–84.London: Edward Arnold [Google Scholar]

- Tadei WP, Thatcher BD, Santos JMM, Scarpassa VM, Rodrigues IB, Rafael MS.(1998)Ecologic observations on anopheline vectors of malaria in the Brazilian Amazon. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 59325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittor Y, Gilman RH, Tielsh J, Glass G, Shields T, Sanchez-Lozano W, Pinedo-Cancino VV, Patz JA.(2006)The effect of deforestation on the human biting rate of Anopheles darlingi, the primary vector of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Peruvian Amazon. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 743–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittor Y, Pan W, Gilman RH, Tielsch J, Glass G, Shields T, Sanchez-Lozano W, Pinedo VV, Salas-Cobos E, Flores S, Patz JA.(2009)Linking deforestation to malaria in the Amazon: characterization of the breeding habitat of the principal malaria vector, Anopheles darlingi. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 815–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrell DA.(2002)Clinical features of malaria Essential Malariology 4th Edneds Warrell D A, Gilles H M.pp. 191–205.London: Edward Arnold [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz RA, Burkot TR, Graves PM, Andre RG.(1987)Field evaluation of enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax sporozoites in mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from Papua New Guinea. Journal of Medical Entomology 24433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz RA, Sattabonkgot J, Hall J, Burkot TR, Rosenberg R.(1992)Development and evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Plasmodium vivax VK 247 sporozoites. Journal of Medical Entomology 29854–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]