Abstract

Two large studies in populations selected for CVD demonstrated that raising HDL cholesterol with niacin added to statin therapy did not decrease CVD. We examine the association of lipoprotein subfractionswith niacin and changes in coronary stenosis and CVD event risk. One hundred and seven individuals from two previous studies using niacin in combination with either statin or bile acid binding resin were selected to evaluate changes in lipoproteins separated by density gradient ultracentrifugation to progression of coronary artery disease as assessed by quantitative coronary angiography. Improvement in coronary stenosis was significantly associated with the decrease of cholesterol in the dense LDL particles and across most of the IDL and VLDL particles density range, but, not with any of the HDL fraction or of the more buoyant LDL fractions. Event free survival was significantly associated with decrease in cholesterol of the dense LDL and IDL; there was no association with changes in cholesterol in the HDL and buoyant LDL fractions. Niacin combination therapy raises HDL cholesterol and decreases dense LDL and intermediate density lipoprotein cholesterol. Changes in LDL and IDL are related to improvement in CVD. Lipoprotein subfraction analysis should be performed in larger studies utilizing niacin in combination with statins.

Keywords: Niacin, TG rich lipoprotein, LDL and HDL density subfractions, coronary artery disease, cardiovascular events

Introduction

Although statins provide 25% to 40% reduction in cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, there is considerable residual risk of CVD events with this therapy (1). Failure of recent trials (2-6) to provide evidence of additional clinical benefit by raising HDL-C levels in addition to the conventional, statin-based strategy, supports a recent meta-regression analysis suggesting that simply increasing the amount of circulating HDL-C with drugs does not reduce the risk of coronary heart disease events, coronary heart disease deaths, or total deaths (7,8). No agent, however, solely increases HDL-C. For instance, niacin increases HDL-C up to30% but concomitantly reduces LDL-C, triglycerides, and lipoprotein(a), and small, dense LDL (9). In several previous studies (10-12), niacin therapy led to significant risk reductions in clinical events. In the present study, we analyzed pooled data from previous angiographic trials by us (11,12) where niacin was used in combination with a second lipid-lowering agent, either colestipol or simvastatin, with the aim of evaluating lipoprotein subfractions as they might account for changes in coronary angiography and clinical benefits.

Methods

One hundred and seven subjects, of the initial 109 patients on niacin-based combination therapy, with clinically established or anatomically demonstrated coronary artery disease (CAD) who participated in the Familial Atherosclerosis Treatment Study (FATS) in 146 men (11), which was completed in 1989, and in the HDL-Atherosclerosis Treatment Study (HATS) in 160 men and women (12), completed in 1999, were included in this analysis. No lipoprotein subclass analysis was available in two of the 109 original patients. Patient characteristics in FATS and HATS have been previously reported (11,12). In this retrospective analysis we included only those patients randomized to receive niacin (up to 4 g per day as tolerated) as part of their lipid lowering strategy which also included colestipol (up to 10 g tid; n=36) in FATS or simvastatin (up to 20 mg per day; n=73) in HATS. The prespecified primary clinical end point was the time to the first of the following events: death from coronaryartery disease, enzymatically confirmed nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularization for worsening ischemia. These events were collected and documented as previously described (11,12).

Coronary angiography was performed using a defined sequence of viewing angles (11,12). A detailed coronary map was drawn that included all lesions causing a digital caliper-measured stenosis of ≥15% of luminaldiameter. The lesion causing the most severe stenosis in each of 9 standard proximal segments was measured using computer-assisted methods in each patient at baseline and follow-up coronary angiography at 2.5 to 3 years. Mean change in severity (percent change) of 9proximal stenoses between the 2 angiograms was the pre-specified primary end point of these studies.

Non-equilibrium density-gradient ultracentrifugation (DGUC) for apo B–containing lipoproteins: This technique, designed to optimize the resolution of apo B–containing lipoproteins, is a modification of a previous method (9). Cholesterol was measured as the absolute value in 37 fractions. Each lipoprotein subclass elution range was defined as previously described (13). DGUC data on lipoprotein physico-chemical properties parallel those made using the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for VLDL and LDL, however DGUC does not discriminate as well as NMR for HDL subfractions (14).

Blood samples were collected and centrifuged (for 10 min at 1600 rpm) at 4C° shortly after collection; plasma was immediately aliquoted, snap frozen and stored at -80°C for later analyses. Plasma triglycerides (Wak o Chemical GmbH) and cholesterol (CHOD-Pap, Roche/Hitachi) were evaluated by standardized enzymatic methods.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 11.0 for Windows (Chicago, Illinois, USA). Results are reported as mean±SD, if not otherwise stated. Group differences in continuous variables were determined by using Student's t test. Logistic regression analysis or multiple linear regression analysis was carried out depending upon the presence of a dichotomous or continuous linear dependent variable. Group differences or correlations with p < 0.05 were deemed as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and baseline biochemical parameters in niacin-treated patients from FATS and HATS have been previously described (11, 12). The baseline lipid phenotypes are, at least partly, dependent upon the study inclusion criteria. Specifically, total and LDL-C levels were higher in FATS and similarly HDL-C was significantly lower in HATS (Table 1). Changes in each lipoprotein level on therapy were significant (p<0.001) as compared to baseline values.

Table 1. Lipids parameters: baseline values and % changes from baseline after therapy.

| FATS: Niacin-Colestipol (N=35) |

HATS: Niacin-Simvastatin (N=32) |

HATS: Niacin-Simvastatin-Vit. (N=40) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | % Change | Baseline | % Change | Baseline | % Change | |

| CHOL (mg/dL) | 270±53 | -23* | 201±48 | -31* | 199±33 | -27* |

| Triglycerides | 194±89 | -30* | 202±85 | -38* | 236±97 | -31* |

| VLDL-C | 42±18 | -45* | 38±18 | -40* | 43±16 | -28* |

| LDL-C | 190±54 | -33* | 132±54 | -43* | 124±46 | -37* |

| HDL-C | 39±7 | +41* | 31±15 | +29* | 30±10 | +20* |

: p<0.001 vs. baseline

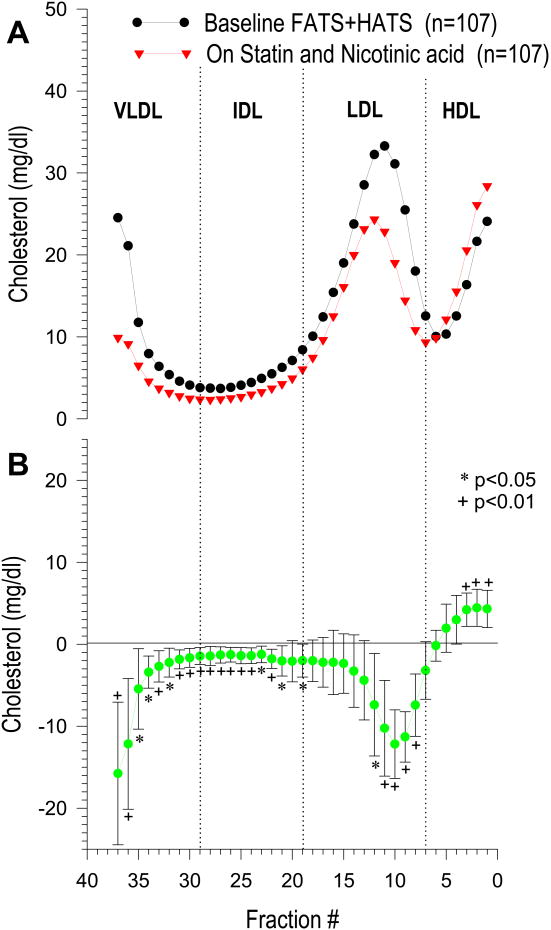

Patients from the two angiographic studies who were on niacin-based combination therapy (n=107) were pooled for the DGUC analysis of cholesterol distribution across the lipoprotein density range. Cholesterol distribution profiles at baseline and on therapy (Figure 1 panel A) and the mean difference profile (on vs. off therapy) (Figure 1 panel B) showed a significant increase on treatment in most of the HDL fractions (fraction 1 to 3; p<0.01 for all), while LDL cholesterol significantly decreased only in the dense LDL (fractions 8 to 11, p<0.01; and fraction 12, p< 0.05), with a similar non-significant trend observed in the more buoyant LDL fractions. When patients from FATS and HATS selected for the present study were analyzed separately, comparable results were observed with a significant cholesterol reduction on therapy only in the dense LDL particles but not in the more buoyant LDL (data not shown). TG-rich lipoprotein subclasses were overall affected by niacin and either colestipol or simvastatin, as highlighted in Figure 1: a significant cholesterol reduction was observed across the IDL (fractions 20-29) and VLDL (fractions 30-37) density range.

Figure 1.

Cholesterol distribution profile in niacin treated patients from FATS and HATS at baseline and after treatment (n=107). Cholesterol (mg/dl) is expressed as absolute value in each fraction.

Panel A: cholesterol content of each lipoprotein subfraction at baseline (black circles) and on niacin combo therapy (red triangles).

Panel B: mean difference profile of cholesterol content of each lipoprotein subfraction on therapy vs. baseline: values were obtained by subtracting cholesterol of each single fraction at baseline from the corresponding fraction on therapy. DGUC profiles were compared by calculating the mean and 95% confidence intervals of the difference for each fraction (18).*p<0.05;+p<0.01

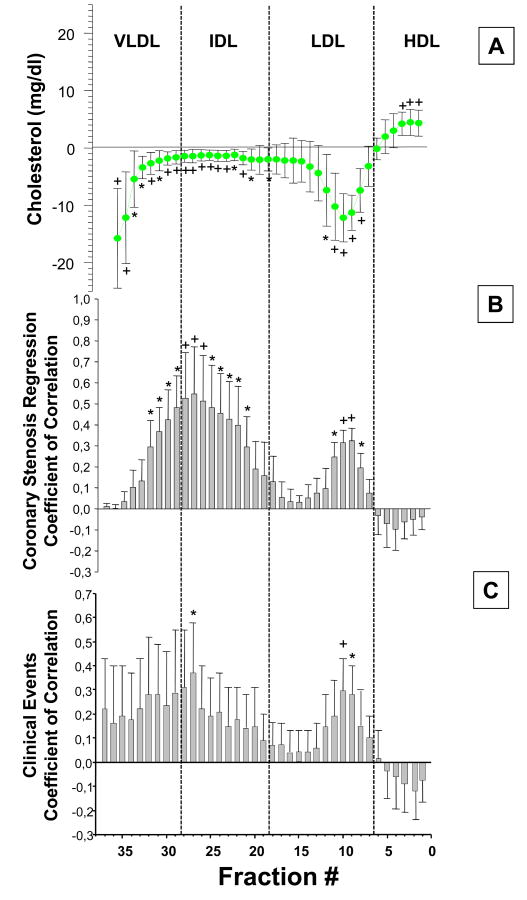

We analyzed the potential contribution to the angiographic and clinical benefits observed in FATS and HATS, accounted by cholesterol changes with niacin and simvastatin/colestipol in each of the lipoprotein fractions separated by DGUC. A multiple linear regression analysis was performed, with angiographic changes in coronary stenosis as the dependent variable and by adjusting the effect of on-therapy changes in cholesterol by gender, age, BMI, and baseline lipid values including LDL-C, HDL-C and TG. Correlation coefficients are reported for each multiple regression analysis involving each single DGUC fraction. A significant association was observed between the improvement in coronary stenosis and the decrease of cholesterol in the dense LDL particles (fraction 8 and 11, p<0.05; fractions 9 and 10, p<0.01) and across most of the IDL density range and the denser VLDL particles (fraction 30-32). No significant association was found between angiographic benefits and cholesterol changes of any of the HDL fraction or of the more buoyant LDL fractions (Figure 2 panel B).

Figure 2.

Changes in Cholesterol across lipoprotein subfractions and their correlation with angiographic changes in niacin treated FATS and HATS patients, and clinical events.

Panel A: mean difference profile of cholesterol content of each lipoprotein subfractionon therapy vs. baseline (same as panel B, figure 1)

Panel B: Correlation by multiple linear regression model between changes in cholesterol in each lipoprotein subfraction, on therapy vs. baseline, and angiographic changes (n=107).

Bars represent correlation coefficients (std. errors) after adjustment for gender, age, BMI, baseline LDL-C, HDL-C and TG. *p<0.05; +p<0.01

Panel C: Correlation, by multiple logistic regression analysis, between changes in cholesterol in each lipoprotein subfraction, on therapy vs. baseline, and primary clinical endpoints in niacin treated HATS and FATS patients.

Total number of primary endpoint events recorded: n=9.

Primary end point in HATS includes: death from coronary causes, confirmed myocardial infarction or stroke, or revascularization for worsening ischemic symptoms. In FATS same as above but without stroke. *p<0.05; +p<0.01

A logistic regression analysis was performed on pooled clinical primary endpoints in niacin treated FATS and HATS, a composite of death from coronary causes, confirmed myocardial infarction or stroke or revascularization for worsening ischemic symptoms and on-therapy cholesterol induced changes in the all the lipoprotein subclasses. A total of 9events, falling into the primary endpoint definition, were recorded. Coefficients of correlation and their standard errors are presented for each logistic regression involving each single lipoprotein fraction as shown in Figure 2 panel C. A significant association was observed between event free survival and decrease in cholesterol of the dense LDL (fractions 9-10) and of fractions 27, within the buoyant IDL range. A consistent, although not statistically significant trend was also observed across all the TG-rich lipoprotein subclasses. Changes in cholesterol in the HDL and buoyant LDL fractions were not associated with incidence of primary clinical endpoints (Figure 2 panel C).These results should be interpreted with caution in the light of the small number of events observed (n=9).

Discussion

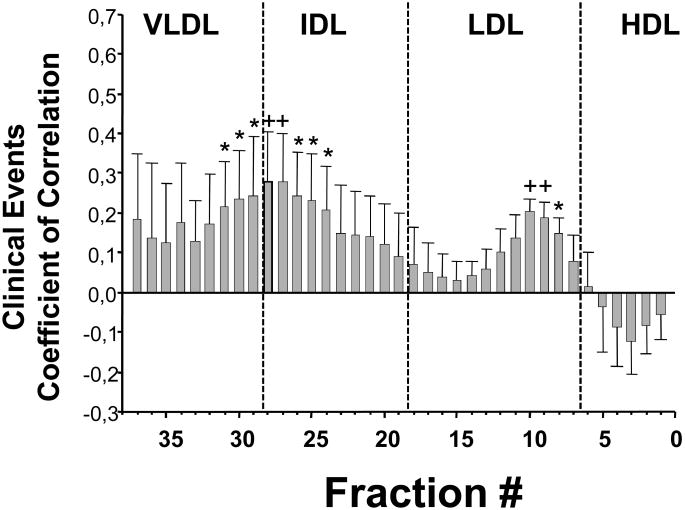

In this hypothesis-generating analysis, involving niacin combination therapy in dyslipidemic middle aged adults with CAD, on treatment cholesterol density distribution changed significantly in multiple lipoprotein subfractions. The changes in IDL (probably remnant lipoproteins) and in the dense LDL particles correlated with regression in coronary stenosis and CVD events. Although there was a significant increase in HDL-C subfractions, these changes were not associated with changes in coronary stenosis nor in CVD event rate. A broader analysis of the whole populations in FATS-HATS (n=280 patients), considering all treatment groups and a total of 40 clinical events, provides strong support to our findings confirming a significant association between changes on therapy in the dense LDL and across the IDL-VLDL 0lipoproteins and clinical CVD event rate (Figure 3), an association was not observed with changes in HDL-C.

Figure 3.

Correlation, by multiple logistic regression analysis, between changes in cholesterol in each lipoprotein subfraction, on therapy vs. baseline, and primary clinical endpoints in the whole population from HATS and FATS (n=280).

Total number of primary endpoint events recorded: n=40.

Primary end point in HATS includes: death from coronary causes, confirmed myocardial infarction or stroke, or revascularization for worsening ischemic symptoms. In FATS same as above but without stroke. *p<0.05; +p<0.01

Epidemiological studies suggest that a high level of HDL-C is protective against CVD (15-17). Although previous clinical trials (10,18) showed that treatment with nicotinic-acid or fibric acid derivatives was effective to reduce CVD events when used as a comparison to placebo, however, contemporary data does not support the hypotheses that increasing HDL-C reduces additional CVD risk when they are used in combination with statin (3,4,6). Another class of drugs, cholesterylester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors, clearly increase HDL-C by as much as 50% do not reduce CVD events (2,5). Recent studies on HDL metabolism would suggest that HDL-C is a rather crude and inadequate measure of the antiatherogenic potential of these lipoproteins, while evidence is mounting that HDL “functionality” is also a relevant parameter to account for their atheroprotective effect (19,20). A possible alternative explanation of this conflicting evidence, as highlighted by the present analysis, is that remnant lipoproteins (dense VLDL and IDL) and small, dense LDL, and consequently their changes with niacin, are clinically more relevant than the effect on HDL-C levels.

The atherosclerotic lipoprotein phenotype (ALP) described for the first time a set of lipoprotein abnormalities that seemed to occur together, rather than as individual lipoprotein abnormalities. ALP included hypertriglyceridemia, increased small and medium size LDL particles and low HDL2 cholesterol (21,22). Increased small LDL and decreased HDL2 were both found to predict future CVD in the Quebec Cardiovascular Study of randomly selected men followed for 13 years (23) and more recently ALP again was demonstrated to be predictive of CVD in 4594 healthy men and women in Sweden followed for 12 years (22). In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis the adjusted risk for developing CVD in 4387 individuals was increased in those with small LDL (24).ALP was an entity independent of risk associated with isolated increased LDL-C levels or isolated decreased HDL-C levels. In the FATS study, patients with familial combined hyperlipidemia with small-dense LDL (25) and those with elevated lipoprotein (a) levels, also characterized by small dense LDL had regression of their coronary stenosis related to change in density of LDL (26). Those who had big, buoyant LDL particles, as seen in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, did not have regression of their coronary stenosis (26). This suggests that only those with small, dense LDL benefit from changes in LDL particle characteristics. Recent analysis of lipoprotein subfractions in HATS (27) also demonstrated small LDL to be associated with CVD. In AIM-HIGH, a recent analysis (28) of patients on niacin divided into those with high TG and low HDL-C suggested a non-significant borderline benefit of niacin in this specific subgroup (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.80-1.09) while no clinical benefits were observed in patients studied according to TG or HDL-C tertiles (28). Also, AIM-HIGH indicated that change in ApoB, ApoA1 and Lp (a) levels was not associated with clinical benefit (29).In the present selected FATS-HATS population on combination therapy, mean baseline TG levels were in the range of 200 mg/dl (2.3 mmol/L) while in AIM-HIGH median TGs concentration was 161 mg/dl (1.8 mmol/L) (4). The present analysis showed a significant angiographic and clinical benefit associated with changes in cholesterol of VLDL/IDL and dense LDL particles, we would hypothesize that patients on niacin with high triglycerides would have a greater CVD benefit that those with normal-low plasma triglycerides by maximizing the benefits associated with a significant decrease of TG-rich VLDL, their remnants and dense LDL particles. Normo-triglyceridemic individuals do not have the lipid phenotype with increased lipoprotein remnants and dense LDL (9), thereby limiting the potential benefits on coronary stenosis and CVD events associated with changes in these lipoproteins. Additional individuals at risk for CVD with small, dense LDL particles might benefit form niacin combination therapy (30). It is important to confirm these findings in large clinical trials such as AIM-HIGH.

We conclude that niacin combination therapy raises HDL-C and decreases dense LDL and TG-rich lipoproteins such as IDL and VLDL. Changes in dense LDL and IDL are related to improvement in CVD. In patients with CVD, combination of a second lipid-lowering agent, i.e. niacin, to a statin based approach requires a careful clinical and lipid phenotyping as a necessary step to maximize likelihood of CVD benefits and effectively tackle the barrier of residual cardiovascular risk. In patients with CVD, persistently elevated TGs and low HDL-C are significant component of this responsive phenotype.

Acknowledgments

FATS was supported by NHLBI grants P01 HL30086 and R01 HL19451.HATS was supported in part by NHLBI grant R01 HL49546. Both studies were also supported with NIH funding through the Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (DK 35816) and the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (DK 17047) at the University of Washington.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Zambon is a member of a lipid related advisory board for Roche. Dr. Brown was a co-principal investigator for AIM-HIGH. Dr. Zhao receives research grants from Abbott, Daiichi-Sankyo, Merck and Pfizer. Dr. Brunzell is a member of a lipid related advisory board for uniQure, Merck, Novartis and ISIS.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fruchart JC, Sacks F, Hermans MP, Assmann G, Brown WV, Ceska R, Chapman MJ, Dodson PM, Fioretto P, Ginsberg HN, Kadowaki T, Lablanche JM, Marx N, Plutzky J, Reiner Z, Rosenson RS, Staels B, Stock JK, Sy R, Wanner C, Zambon A, Zimmet P. The Residual Risk Reduction Initiative: a call to action to reduce residual vascular risk in patients with dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1K–34K. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(08)01833-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Komajda M, Lopez-Sendon J, Mosca L, Tardif JC, Waters DD, Shear CL, Revkin JH, Buhr KA, Fisher MR, Tall AR, Brewer B ILLUMINATE Investigators. Effects of torcetrapib in patients with high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2109–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACCORD Study Group. Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, Crouse JR, 3rd, Leiter LA, Linz P, Friedewald WT, Buse JB, Gerstein HC, Probstfield J, Grimm RH, Ismail-Beigi F, Bigger JT, Goff DC, Jr, Cushman WC, Simons-Morton DG, Byington RP. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1563–1574. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterollevels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, Brumm J, Chaitman BR, Holme IM, Kallend D, Leiter LA, Leitersdorf E, McMurray JJ, Mundl H, Nicholls SJ, Shah PK, Tardif JC Wright RS for the dal-OUTCOMES Investigators. Effects of Dalcetrapib in Patients with a Recent Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2089–2099. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. HPS2-THRIVE randomized placebo-controlled trial in 25 673 high-risk patients of ER niacin/laropiprant: trial design, pre-specified muscle and liver outcomes, and reasons for stopping study treatment. European Heart Journal. 2013;34:1279–1291. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briel M, Ferreira-Gonzalez I, You JJ, Karanicolas PJ, Akl EA, Wu P, Blechacz B, Bassler D, Wei X, Sharman A, Whitt I, Alves da Silva S, Khalid Z, Nordmann AJ, Zhou Q, Walter SD, Vale N, Bhatnagar N, O'Regan C, Mills EJ, Bucher HC, Montori VM, Guyatt GH. Association between change in high density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMJ. 2009;338:b92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jun M, Foote C, Lv J, Neal B, Patel A, Nicholls SJ, Grobbee DE, Cass A, Chalmers J, Perkovic V. Effects of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1875–1884. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zambon A, Hokanson JE, Brown BG, Brunzell JD. Evidence for a New Pathophysiological Mechanism for Coronary Artery Disease Regression Hepatic Lipase–Mediated Changes in LDL Density. Circulation. 1999;99:1959–1964. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.15.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canner PL, Berge KG, Wenger NK, Stamler J, Friedman L, Prineas RJ, Friedewald W. Fifteen year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients; long term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown BG, Albers JJ, Fisher LD, Schaefer SM, Lin JT, Kaplan C, Zhao XQ, Bisson BD, Fitzpatrick VF, Dodge HT. Regression of coronary artery disease as a result of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in men with high levels of apolipoprotein B. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1289–1298. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011083231901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown BG, Zhao XQ, Chait A, Fisher LD, Cheung MC, Morse JS, Dowdy AA, Marino EK, Bolson EL, Alaupovic P, Frohlich J, Albers JJ. Simvastatin and niacin, antioxidant vitamins, or the combination for the prevention of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1583–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capell WH, Zambon A, Austin MA, Brunzell JD, Hokanson JE. Compositional differences of LDL particles in normal subjects with LDL subclass phenotype A and LDL subclass phenotype B. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:1040–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg R, Temprosa M, Otvos J, Brunzell J, Marcovina S, Mather K, Arakaki R, Watson K, Horton E, Barrett-Connor E. Lifestyle and metformin treatment favourably influence lipoprotein subfraction distribution in the diabetes prevention program. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3989–3998. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, Neaton JD, Castelli WP, Knoke JD, Jacobs DR, Jr, Bangdiwala S, Tyroler HA. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies. Circulation. 1989;79:8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson PW, Abbott RD, Castelli WP. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality. The Framingham Heart Study. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:737–741. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, Iranmanesh A, Wilt TJ, Mann D, Mayo-Smith M, Faas FH, Elam MB, Rutan GH. Distribution of lipids in 8,500 men with coronaryartery disease. Department of Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80761-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robins SJ, Collins D, Wittes JT, Papademetriou V, Deedwania PC, Schaefer EJ, McNamara JR, Kashyap ML, Hershman JM, Wexler LF, Rubins HB VA-HIT Study Group. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial. Relation of gemfibrozil treatment and lipid levels with major coronary events: VA-HIT: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1585–1591. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de la Llera-Moya M, Drazul-Schrader D, Asztalos BF, Cuchel M, Rader DJ, Rothblat GH. The ability to promoteefflux via ABCA1 determines the capacity of serumspecimens with similar high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to remove cholesterol from macrophages. ArteriosclerThromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:796–801. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.199158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Lioera-Moya M, Rodriques A, Burke M, Jafri K, French B, Phillips JA, Mucksavage ML, Mohler ER, Rothblat GH, Rader D. Cholesterol efflux capacity and atherosclerosis. N Eng J Med. 2011;364:127–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin MA, Breslow JL, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Willett WC, Krauss RM. Low-density lipoprotein subclass patterns and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1988;260:1917–1921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musunuru K, Orho-Melander M, Caulfield MP, Li S, Salameh WA, Reitz RE, Berglund G, Hedblad B, Engström G, Williams PT, Kathiresan S, Melander O, Krauss RM. Ion mobility analysis of lipoprotein subfractions identifies three independent axes of cardiovascular risk. Arterioscler ThrombVasc Biol. 2009;29:1975–1980. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.190405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.St-Pierre AC, Cantin B, Dagenais GR, Mauriège P, Bernard PM, Després JP, Lamarche B. Low-density lipoprotein subfractions and the long-term risk of ischemic heart disease in men: 13-year follow-up data from the Québec Cardiovascular Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:553–559. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000154144.73236.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai MY, Steffen BT, Guan W, McClelland RL, Warnick R, McConnell J, Hoefner DM, Remaley AT. New Automated Assay of Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Identifies Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:196–201. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayyobi AF, McGladdery SH, McNeely MJ, Austin MA, Motulsky AG, Brunzell JD. Small, dense LDL and elevated apolipoprotein B are the common characteristics for the three major lipid phenotypes of familial combined hyperlipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1289–1294. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000077220.44620.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zambon A, Brown BG, Hokanson JE, Motulsky AG, Brunzell JD. Genetically determined apo B levels and peak LDL density predict angiographic response to intensive lipid-lowering therapy. J Intern Med. 2006;259:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams PT, Zhao XQ, Marcovina SM, Brown BG, Krauss RM. Levels of cholesterol in small LDL particles predict atherosclerosis progression and incident CHD in the HDL-Atherosclerosis Treatment Study (HATS) PloS One. 2013;8:e56782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyton JR, Slee AE, Anderson T, Fleg JL, Goldberg RB, Kashyap ML, Marcovina SM, Nash SD, O'Brien KD, Weintraub WS, Xu P, Zhao XQ, Boden WE. Relationship of lipoproteins to cardiovascular events: the AIM-HIGH Trial (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome With Low HDL/High Triglycerides and Impact on Global Health Outcomes) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1580–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albers JJ, Slee A, O'Brien KD, Robinson JG, Kashyap ML, Kwiterovich PO, Jr, Xu P, Marcovina SM. Relationship of apolipoproteins A-1 and B, and lipoprotein(a) to cardiovascular outcomes: the AIM-HIGH trial (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglyceride and Impact on Global Health Outcomes) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1575–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, Goldberg IJ, Sacks F, Murad MH, Stalenhoef AF Endocrine society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2969–2989. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]