Abstract

Salmonella infections can cause a range of intestinal and systemic disease in human and animal hosts. While some Salmonella serovars initiate a localized intestinal inflammatory response, others use the intestine as a portal of entry to initiate a systemic infection. Considerable progress has been made in understanding bacterial invasion and dissemination strategies and the nature of the Salmonella-specific immune response to oral infection. Innate and adaptive immunity are rapidly initiated after oral infection but these effector responses can also be hindered by bacterial evasion strategies. Furthermore, although Salmonella resides within intramacrophage phagosomes, recent studies highlight a surprising collaboration of CD4 Th1, Th17, and B cell responses in mediating resistance to Salmonella infection.

Introduction

Salmonella infections cause intestinal and systemic disease in human and animal hosts and are an important public health priority worldwide (1–3). Greater understanding of the immune response to Salmonella is required in order to provide a solid foundation for the development of new and improved vaccines against these infections. Furthermore, the complex interplay between the host immune response and bacterial virulence factors during Salmonella infection provide an ideal model to understand the biological intersection of two competing genomes. Indeed, there is a long history of microbiologists and immunologists examining the murine model of Salmonella infection since it allows examination of these important issues while also allowing a natural oral route of infection (4–10). This review will focus on our current understanding of bacterial dissemination and host immunity following oral infection with Salmonella with a particular emphasis on the most recent findings from the murine model.

Disease caused by Salmonella infection

Salmonella is a Gram-negative facultative intracellular pathogen that is able to cause a spectrum of clinical disease depending on the infecting bacterial serovar and underlying host susceptibility (11). Salmonella infections fall broadly into three categories, (i) localized intestinal infection (gastroenteritis), (ii) systemic infection of an otherwise healthy host (typhoid), (iii) systemic infection of a selectively susceptible or immune compromised host (non-typhoidal Salmonellosis).

Salmonella gastroenteritis

Large Salmonella outbreaks associated with the ingestion of contaminated food products are now a common occurrence (12–14). In the US, around 50% of food-borne infections are caused by bacteria, and approximately 30–50% of these can be attributed to Salmonella serovars (15, 16). Patients suffer from a localized intestinal infection that includes fever, diarrhea, and cramping, but most healthy individuals recover without treatment within 4–7 days (9). In contrast, patients with weakened immune status or underlying health conditions can develop a fatal infection during these outbreaks, and Salmonella remains a leading cause of food-borne fatalities in the US (1, 15). Importantly, these intestinal infections can be initiated by any one of around 2000 different Salmonella serovars that are able to infect humans and various animal reservoirs.

Typhoid fever

Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi are the causative agents of typhoid fever, a disease characterized by fever and hepatosplenomegaly, with subsequent intestinal hemorrhage or perforation also possible (11). These clinically indistinguishable infections are responsible for an estimated 27.1 million cases and 217,000 deaths every year in developing nations (17). Unlike the Salmonella serovars causing gastroenteritis, these particular Salmonella serovars are highly restricted to the human host. Thus, preventative measures such as improving sanitation, food hygiene, and clean drinking water can be effective in disrupting human-to-human transmission (18). However, the substantial improvements in societal infrastructure that would be required to prevent typhoid transmission are cost prohibitive and are unlikely to have a significant impact on reducing typhoid incidence in the near future (19). In contrast, the generation of safe and effective typhoid vaccines that could be used routinely and safely in endemic areas would be more likely to have a significant impact on typhoid (2). There are currently two licensed typhoid vaccines, each with moderate efficacy against this disease (3 year cumulative efficacy of 50–55%), however, neither of these vaccines is widely used in endemic areas (20). The improvement or replacement of these existing vaccines will likely require greater understanding of host immunity to Salmonella infection.

There are also several unusual features of typhoid that suggest the development of incomplete or partial immunity in naturally exposed individuals. First, a chronic carrier condition occurs in a proportion of typhoid patients or exposed asymptomatic individuals (8, 11). This carrier state is caused by persistent gall bladder infection and can result in long-term bacterial shedding in stools with few clinical signs of infection (8, 11). Second, there is some evidence that individuals living in endemic areas suffer from repeated bouts of typhoid, a finding that suggests relatively poor natural development of acquired immunity (11). Third, relapse of primary typhoid is thought to occur in 5–15% of patients following apparent resolution of disease (11, 21). These clinical relapses occur in untreated typhoid patients but are also commonly observed following antibiotic treatment of primary infection (22–25). Each of these clinical issues highlights the perplexing ability of Salmonella to persist for extremely long periods in an otherwise immune competent host and/or the failure of acquired immune responses to effectively resolve primary or secondary infection. Understanding the immunological basis of these issues would likely provide a clearer understanding of protective immunity in the infected host and may also be key to the improvement of vaccine development against typhoid. Fortunately, animal models are now available that allow detailed study of persistent bacterial shedding (26, 27), antibiotic-mediated relapsing disease (Griffin et al, submitted), and the perplexing failure of the host to develop robust immunity following primary infection (28). It is therefore likely that bacterial virulence factors and the immunological parameters associated with these clinical issues can be elucidated in the future.

Disseminated Non-typhoidal Salmonellosis (NTS)

As noted above, non-typhoidal serovars of Salmonella normally cause gastroenteritis but can also cause fatal infections when host immunity is compromised (29). These non-typhoidal serovars can also cause disseminated infections that lack gastrointestinal symptoms and may be transmitted by human-to-human contact rather than via an animal reservoir (30–32). These unusual features are likely to be caused by ongoing host adaptation of NTS strains in endemic areas (33). There is currently no vaccine against NTS and greater understanding of host immunity to disseminated infection is required. While this disease is relatively rare in developed nations, disseminated NTS infections are increasingly associated with HIV-infected individuals in Asia and Africa (29, 34–36). In addition, a small cohort of patients with primary IL-12 and IL-23 signaling deficiencies display markedly increased susceptibility to NTS (37), and these cytokines are important for differentiation of Th1 and Th17 cells. Disseminated NTS has also been reported to occur in HIV-negative young children and the fatality rate of these patients is high (30, 31). Evidence from these young patients suggests that the development of Salmonella-specific antibody contributes to the development of protective immunity against NTS (38). Taken together, these findings suggest a requirement for CD4 Th1 and Th17 cells, plus an essential role for antibody in the resolution of NTS. Indeed, a similar conclusion can also be drawn from mouse studies that will be discussed in more detail below.

Mouse models of Salmonella infection

Microbiologists and Immunologists have examined immunity to Salmonella in mice because this model is easy to work with in the laboratory and reproduces many important aspects of human Salmonellosis (39). As might be expected, this animal model has some limitations, most notably that Salmonella-infected mice do not develop diarrhea, although this is also a variable symptom in human systemic Salmonellosis. Study of the bacterial and host processes leading to Salmonella gastroenteritis are therefore best examined using larger animal models (9). However, pretreatment of mice with antibiotics allows for rapid development of intestinal colitis in response to Salmonella infection, and this model is now widely used to examine the inflammatory responses accompanying intestinal bacterial infection (40). This approach to examining gastrointestinal inflammation has its own limitations since it requires the unphysiological elimination of the microbiota and uses strains of Salmonella that may also cause systemic disease. However, it represents a useful murine model to understand gastrointestinal inflammation in response to oral infection. The murine model of Salmonella colitis has been reviewed in detail (41), and will therefore not be discussed in any depth in this current review.

Another perceived limitation of the mouse model is that systemic infection can be initiated following infection with Salmonella serovars Typhimurium or Enteritidis, while neither of these serovars causes human typhoid. However, it should be noted that both these serovars can cause systemic Salmonellosis in susceptible humans. As noted above, the serovars that cause typhoid are exquisitely adapted to humans and therefore cannot be examined in mice after oral infection (42). This discordance in serovar susceptibility between mouse and human causes an inevitable disconnection between clinicians working on immunity to human typhoid and basic scientists studying immunity to oral Salmonella infection in mice. This is unfortunate, as a deeper understanding of immunity to systemic Salmonellosis in the mouse model is likely to have implications for our understanding of systemic human Salmonellosis, whether due to NTS or typhoid serovars. However, it is currently unclear whether disseminated Salmonellosis in the murine model can serve as a useful preclinical model of typhoid or represents something more akin to the NTS in immune compromised individuals. A decent argument can be made for the latter interpretation since highly susceptible mouse strains that succumb to Salmonella express a susceptible allele of the Slc11a1 gene (formerly known as Nramp-1) allowing uncontrolled bacterial growth (8). However, it should also be noted that innately resistant mice expressing the resistant allele of Slc11a1 also develop disseminated persistent infections with Salmonella (26). Perhaps greater understanding of antigen targeting by the adaptive immune response during human typhoid, NTS, and murine infection will have the potential to resolve whether and how these infections are related and may be helpful in validating or excluding murine infection as a relevant model for important preclinical vaccine studies.

Oral Salmonella infection and the establishment of systemic infection

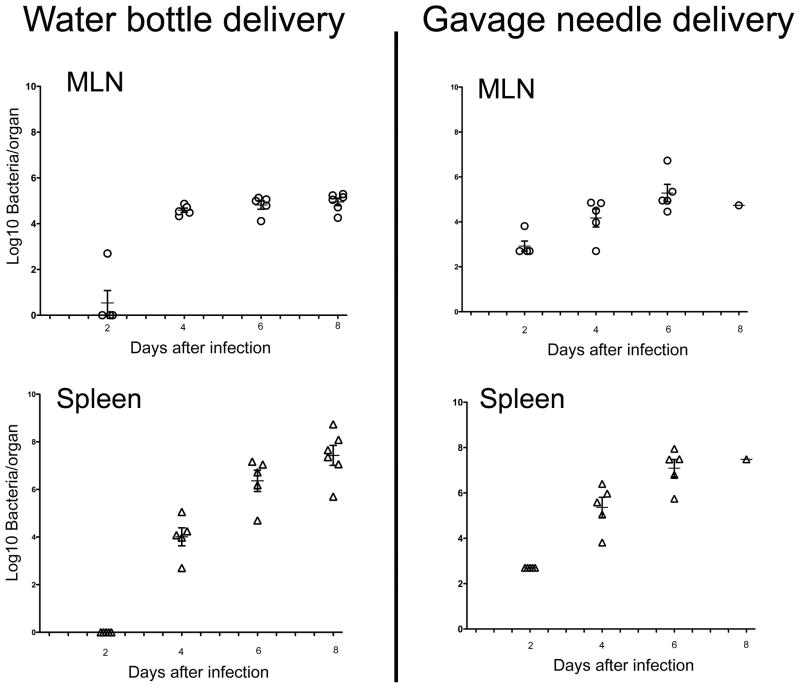

Although immunity to Salmonella in mice is often studied after intra-peritoneal, intravenous, or sub-cutaneous infection, in most cases there is no clear justification for using these challenge routes. Indeed, one of the clear advantages of the mouse model is that Salmonella can be administered orally and intestinal mucosa penetration will occur via natural expression of bacterial virulence factors (43, 44). In some laboratories, orally infected mice are pretreated with sodium bicarbonate to neutralize stomach pH, or may also be fasted for a short period, prior to delivery of Salmonella by gavage (45). While these pre-treatments are not absolutely essential, they serve to reduce mouse-mouse variability in this model and are therefore useful experimentally. Arguably, the most natural method of Salmonella delivery is to simply add virulent organisms to mouse drinking water. Indeed, our laboratory have examined this methodology and have found that mice are reliably infected using this approach, and the rate of infection and dissemination is very similar to mice administered bacteria via gavage inoculation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of Salmonella infection following gavage inoculation or water bottle administration.

Groups of C57BL/6 mice were orally infected with 5×107 cfu of virulent S. typhimurium (SL1344) by gavage needle while other mice were supplied with drinking water contaminated with SL1344 (1×107 cfu/ml). Organs were harvested at the indicated time points after infection and bacterial loads were determined by plating organ homogenates on MacConkey’s agar. Data show individual mice and mean bacterial load +/− SD per time point.

Peyer’s patches are a portal of entry for Salmonella

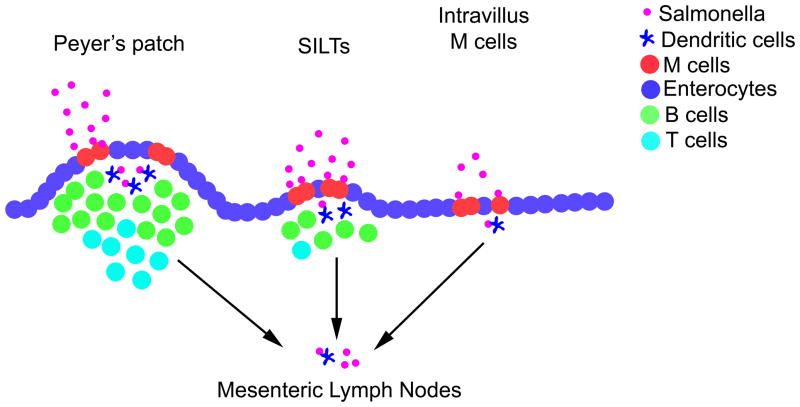

Upon ingestion of Salmonella by the host, bacteria travel from the stomach to the small intestine where they can be transported across the intestinal epithelium. The primary site of Salmonella infection occurs at specialized microfold, or M cells, which are interspersed among the enterocytes covering the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE) of the Peyer’s patch (46) (Figure 2). Salmonella are thought to preferentially invade Peyer’s patches in the distal ileum but in practice all intestinal Peyer’s patches will harbor bacteria after moderate to high dose infection. Early studies found that Salmonella were associated with Peyer’s patches of orally infected mice within three to six hours of infection (4, 47) and this has been confirmed by more recent temporal studies (48, 49).

Figure 2. M cell-mediated entry of Salmonella in the small intestine.

Salmonella use SPI-1 gene products to induce uptake and destruction of M cells localized over Peyer’s patches, Solitary Isolated Lymphoid Tissues (SILTs), or scattered throughout the small intestine. The relative importance of these pathways to Salmonella uptake is likely to be Peyer’s patches, followed by SILTs, with intravillus M cells playing a minor role. After entering the underlying tissue, Salmonella are engulfed by phagocytes, including dendritic cells, which can transport bacteria to the draining mesenteric lymph nodes via the afferent lymphatics.

Salmonella expresses a type-III secretion system (TTSS) encoded by Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 1 (SPI-1) that is required for M cell invasion (50). The SPI-1 gene products form a needle-like complex on the bacterial surface that allows injection of effector proteins into the epithelial cell cytosol and initiates pathogen uptake. Characteristic membrane ruffling of M cells occurs following attachment of Salmonella to glycoprotein 2 in a process mediated by the Ipf fimbrial operon and SPI-1 (51–53). Salmonella penetration initiates M cell destruction, thus disrupting the mucosal barrier and also allowing additional entry of bacteria via neighboring enterocytes (46). This process is extremely efficient, with M cell penetration detected within 30 minutes, and M cell destruction observed around 60 minutes after infection (46). After gaining access to the Peyer’s patch via the FAE, Salmonella encounter various phagocyte populations in the underlying sub-epithelial dome (SED). The SED contains dendritic cell (DC) subsets and macrophage populations, each of which can phagocytose Salmonella and then undergo apoptosis induced by the bacteria through a caspase-1-dependent mechanism (54). In macrophages, this process is known as pyroptosis (55), and is mediated by a large, supramolecular complex termed the pyroptosome (56). This mode of cell death may be advantageous for bacterial entry, as dissemination to systemic tissues was found to occur more rapidly in wild-type mice than in caspase-1-deficient mice (57).

M cell-mediated entry outside of Peyer’s patches

Although M cells are concentrated in Peyer’s patches, they are also found in other intestinal locations and can therefore mediate Salmonella infection of non-Peyer’s patch intestinal tissue (Figure 2). The most likely non-Peyer’s patch entry route is via bacterial invasion of solitary intestinal lymphoid tissues (SILTs) which are heterogenous intestinal lymphoid aggregates found in mice and humans that contain certain features of Peyer’s patches, including the presence of an FAE containing M cells (58, 59). As might be expected for a structure containing M cells, these SILTs are targeted for entry by intestinal Salmonella in much the same way as described above for Peyer’s patches (60). Two days after oral Salmonella infection, bacteria were detected by histology in 40% of SILT of BALB/c mice and 17% of SILT of C57BL/6 mice, likely reflecting the greater number of large SILT in BALB/c mice (60, 61). Given the fact that there are more than 1,000 SILT structures in the intestine (60), it seems very likely that this alternative pathway contributes significantly to overall bacterial uptake outside the Peyer’s patch. Evidence also suggests that SILTs can be important in humans, as both Peyer’s patches and SILTs displayed inflammation in a study of typhoid patients (62). It has been also reported that intravillus M cells, which are sparsely located along the intestinal tract, may serve as a portal of entry for invasive Salmonella (63) (Figure 2). Indeed, this appears to be the primary route of Salmonella entry in mice that lack organized lymphoid tissues (63), although the importance of these M cells in normal mice is currently unclear.

Salmonella infection of intestinal lamina propria via direct sampling

While the entry routes described above involve Salmonella interactions with M cells, the possibility that Salmonella can invade the host by an alternative route that does not involve M cells has also been discussed in some detail (64, 65). One interesting possibility is that a population of phagocytes in the lamina propria can capture bacteria directly from luminal contents, thus allowing bacterial entry (65). Crucially, this route does not involve M cell-mediated uptake and is most commonly studied using bacteria that lack SPI-1 genes. Although these cells have often been referred to as dendritic cells, this is by no means clear (66–68), and they will therefore be referred to as lamina propria phagocytes in this review. Although this pathway of entry has now become a popular alternative to our conventional understanding of Salmonella entry via M cells, the physiological relevance of this pathway to systemic Salmonellosis remains undefined.

Although the evidence for a non-M cell pathway is compelling, it derives from a large number of microbiological and immunological investigations that are difficult to reconcile together in a single coherent model. Recent interest was stimulated by an important study demonstrating that Salmonella strains lacking SPI-1 and the fimbrial lpfC gene retained the ability to infect mice in a CD18-dependent manner, and that these bacteria were detected in the blood within 15 minutes of oral inoculation (69). Indeed, prior studies had reported the presence of Salmonella in the blood within 2–3 minutes of oral infection and surprisingly this mode of entry was found to be permissive for bacterial serovars that do not normally infect mice (70). Given the extremely rapid nature of this dissemination to the blood and the lack of serovar specificity, there remains some concern that bacteria enter the blood stream of the host via abrasions caused during the gavage process. When using a bacterial imaging system, we have detected several instances of Salmonella infection of cervical lymph nodes that we attribute to entry via the mucosal abrasions that occur during gavage (Griffin et al, unpublished). Although this is a relatively infrequent occurrence and unlikely to explain the findings above, it does serve to highlight the ability of Salmonella to enter the murine host via unconventional and potentially unphysiological routes. A more recent study has found that bacterial expression of the SPI-2 type-III secretion system effector protein SrfH was required for very early dissemination of Salmonella to the blood and spleen (71). This finding is important and supports the idea that extremely rapid entry via an alternative pathway involves an active and physiological biological process. It is therefore vitally important that this pathway be examined in more detail from a microbiological perspective, especially with respect to the bacterial virulence factors required for entry.

The microbiological studies above are often loosely connected to a series of immunological observations that have examined the capture of luminal bacteria by cells in the lamina propria. However, whether these two processes are in any way connected still remains to be determined. In particular, the extremely rapid kinetics of bacterial entry reported in the studies above are difficult to reconcile with the time frame required for cell-mediated lamina propria entry and trafficking out of the intestine. In vitro studies initially demonstrated that DCs are able to capture bacteria from the apical surface of epithelial cells by extending processes between the tight junctions of a monolayer (72). Subsequently, a similar process was directly visualized in vivo when CX3CR1-expressing phagocytes in the lamina propria were detected extending transepithelial dendrites into the intestinal lumen, and the number of these dendrites increased in the terminal ileum following Salmonella infection (73, 74). Together, these studies suggested an alternative entry model whereby Salmonella might commonly access the intestinal lamina propria via cell sampling, and in support of this idea large numbers of bacteria were detected within the lamina propria (73). However, Salmonella are not normally recoverable in large numbers from the lamina propria unless the bacterial flora are first depleted prior to infection (4, 40, 60). Furthermore, the formation of transepithelial dendrites has been found to be dispensable for the uptake of other pathogenic microbes (75). More importantly, recent analysis of cellular entry into the MLN has demonstrated that CX3CR1-expressing lamina propria cells are unlikely to migrate to the MLN and that these cells have poor immunostimulatory capacity (66). Thus, CX3CR1+ cells most likely represent a population of non-migrating phagocytes that provide innate immune defense against infection within the lamina propria. Given these significant issues, it remains unclear whether this alternative pathway of entry plays an important physiological role, either in promoting bacterial dissemination of Salmonella or in initiating immune activation. The relative contribution of this pathway to bacterial entry and dissemination deserves further study, but it is vitally important that these studies be done in the context of unmanipulated mice using wild-type bacterial strains. Surprisingly, the role of cell-mediated uptake has not been examined carefully in Peyer’s patches or SILTs, yet phagocyte populations are often found in close association to the epithelial layer in each of these tissues (60, 76). In summary, the available data support a prominent role for M-cell mediated intestinal entry by Salmonella, both in the Peyer’s patch and SILTs. Salmonella entry of the lamina propria of unmanipulated mice is less well defined and the mechanisms associated with this route of entry remain largely speculative.

Salmonella infection of mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and systemic tissues

After Salmonella have gained entry to intestinal lymphoid tissues via M cells, it is thought that they travel via afferent lymphatics to the draining mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs), and subsequently disseminate via efferent lymphatics to the blood and systemic tissues (77, 78). The evidence for this step-wise migration is largely based on our understanding of the flow of lymph and the circumstantial finding that bacteria are initially detected in Peyer’s patches, followed by the MLN, and finally in the spleen and liver (4, 48). The trafficking of Salmonella from Peyer’s patches and SILTs to MLNs is most likely accomplished by migration of infected dendritic cells since MLN bacteria were found associated with CD11c+ cells and the number of bacteria in the MLN was also reduced in CCR7-deficient mice (79). However, other studies have noted the migration of free bacteria in afferent lymph suggesting that some bacteria in the MLN may arrive in an extracellular form (77). After reaching the MLN, Salmonella can access efferent lymphatics and spread to systemic tissues via the thoracic duct and blood (77, 78). It is not yet clear which cell population mediates this transport of bacteria to the blood and other tissues, however intestinal DCs are usually discussed as a possibility. In a large animal model that allowed visualization of bacterial transport, the majority of Salmonella were found free in lymph or were associated with non-DC phagocytes (80), but it is not clear whether this also occurs during exit from the MLN. Greater analysis of lymph-mediated transport of Salmonella from the MLN to the blood is therefore required.

Disseminated Salmonella show a tropism for tissues that contain a high number of phagocytic cells, and in most circumstances this involves the spleen, liver, and bone marrow (50, 77). Bacteria are found closely associated with mononuclear phagocytes and induce further recruitment or expansion of monocytic/macrophage cells in each of these locations (50, 77). Salmonella also disrupt the process of erythropoesis and splenomegaly can be explained in large part by the expansion of immature erythrocytes in the spleen in an EPO-dependent manner (81). Cancer studies in mice have demonstrated that Salmonella preferentially accumulate in primary and metastatic tumors (82, 83), suggesting that bacteria do not have a precise organ tropism other than finding tissue that contain a sufficient number of cells that support bacterial replication. Although Salmonella will continue to colonize the Peyer’s patches and MLN, the large size of the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, means that these tissues gradually comprise the major sites of bacterial replication (4, 48). Thus, although Salmonella may be described as an intestinal pathogen, it leads to a systemic infection in mice that simply uses intestinal lymphoid tissues as a portal of entry. This also means that clearance of bacteria from the host and resistance to secondary Salmonella infection requires the coordinated action of both systemic and mucosal immunity.

Initial bacterial replication and the innate immune response to Salmonella

After phagocytosis by macrophages, Salmonella are able to survive and replicate within modified intracellular vesicles, termed Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCVs) (84, 85). Infected macrophages can be activated to kill or limit the replication of Salmonella by producing lysomal enzymes, reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI), reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI), and other antimicrobial peptides (86, 87). The ability of Salmonella to survive within the phagosome is mediated by Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 2 (SPI-2), which encodes a Type-III Secretion System (TTSS) that prevents movement of RNI and ROI into the phagosome where Salmonella reside (86, 88). In addition, the Salmonella phoP/phoQ regulon inhibits fusion of the SCV with toxic lysosomes and endosomes (89, 90). Mice expressing the wild-type allele for the solute carrier family 11a member 1 (Slc11a1) gene, which enables macrophages to transport ions into the SCV, are more resistant to infection with Salmonella (91). In contrast, mice expressing the susceptible allele of the same gene are innately susceptible to very low dose infection (<10 bacteria) and succumb to infection within 7–10 days of oral infection (28). Intracellular survival within tissue phagocytes is key to the virulence of Salmonella, and mutants that cannot survive and replicate within macrophages are severely attenuated for virulence (92).

The initial invasion of Peyer’s patches and SILT induces a massive inflammatory response, characterized by recruitment of neutrophils, DCs, inflammatory monocytes, and macrophages (60, 93). Neutrophils are thought to be important in preventing dissemination of the bacteria from the intestine to systemic tissues and patients with reduced numbers of neutrophils have increased risk of bacteremia during infection with non-typhoidal strains of Salmonella (94, 95). It has also been found that depletion of neutrophils allows Salmonella to grow extracellularly (96), suggesting that neutrophils confine and reduce bacterial replication immediately after entry. Inflammatory monocytes are also important during the initial stages of infection in the Peyer’s patches and MLNs and are an important source of anti-microbial factors such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (93). Recruitment of these inflammatory cells is driven by Myd88-dependent chemokine production initiated within the Peyer’s patch (97). Indeed, Salmonella express several pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagellin, which can be detected by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) expressed by enterocytes and phagocytes (98). In addition, macrophages can sense cytosolic flagellin using NLRC4 (also known as Ipaf, or IL-1β converting enzyme [ICE]-protease activating factor), which activates caspase-1 and induces the production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-18 (99–102).

Dendritic cells are professional antigen-presenting cells and respond to recognition of Salmonella LPS or flagellin by increasing expression of MHC Class II and the co-stimulatory molecules CD80, CD86, and CD40 (103, 104). This maturation process allows dendritic cells to efficiently present antigen to naïve CD4 T cells, thus providing a vital link between innate immune responses and the induction of adaptive immunity. In the Peyer’s patch, flagellin also induces the secretion of the inflammatory chemokine CCL20, which is an important ligand for CCR6 (105). This inflammatory response rapidly recruits CCR6-expressing dendritic cells to the FAE, a very early process that is required for efficient activation of CD4 T cells in the Peyer’s patch (49).

Adaptive immune response to Salmonella

Early T cell activation in the intestine

Given the small size of intestinal lymphoid tissues and the low frequency of naïve CD4 T cells specific for any given antigen (106), detecting initial Salmonella-specific T cell activation in these tissues is challenging. However, a number of studies have used T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice in order to visualize the earliest processes of Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells responding to oral infection (48, 107). While these studies use an artificially elevated naïve precursor frequency of CD4 T cells and a high dose of infection to assist visualization, they still provide the most accurate assessment of Salmonella-specific CD4 T cell activation (108). Together, these studies concur that the earliest Salmonella-specific CD4 T cell activation takes place within the Peyer’s patch and is initiated around 3–6 hours of infection (48, 107). Early activation of CD4 T cells requires the presence of CD11c+ dendritic cells in the Peyer’s patch and is dependent on the expression of CCR6 to recruit DCs to the FAE (49). Interestingly, the TCR transgenic mouse used most frequently in these experiments recognizes a Salmonella peptide from the carboxy terminal region of flagellin (109), which as noted above is also a ligand for TLR5 (110). It is generally assumed that the very early activation of flagellin-specific CD4 T cells in the Peyer’s patch is representative of the naive CD4 response to other Salmonella antigens (108, 111). However, this is difficult to demonstrate conclusively since very few natural Salmonella MHC class-II peptides are known (112). In more recent studies, the kinetics of flagellin-specific CD4 T cell activation was found to be delayed in mice lacking TLR5, adding support to the idea that TLR5 ligation preferentially enhances the adaptive response to flagellin in vivo [Letran et al, in press].

Salmonella-specific T cells also become activated in the MLN after oral infection, but this response usually peaks around 3 hours after that in the Peyer’s patch (48, 49). At these very early time points, Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells were not found to be activated in any other secondary lymphoid tissue (48, 49). This is important because it suggests that whatever the explanation for early bacterial dissemination to blood as discussed above, this does not initiate an early adaptive immune response outside the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). Interestingly, activation of Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells in the MLN is also dependent on CD11c+ DCs and CCR6 indicating that T cell activation in the MLN and PP has similar requirements. There is clear evidence that the MLNs are an important site for immune protection during the course of Salmonella infection. Indeed, mice that have had MLNs surgically removed suffer from elevated bacterial loads and severe immunopathology in the liver (79). The importance of the MLN was also highlighted using a relapsing model of murine typhoid where primary infection returns following apparent antibiotic clearance (Griffin et al, in revision). Mice without MLNs had increased bacterial numbers in systemic tissues following the relapse of primary Salmonella infection (Griffin et al, in revision). Thus, although the MLN is often thought of as a potential site of bacterial persistence (26, 113), it actually provides an important protective function as a firewall preventing bacterial dissemination in primary and relapsing Salmonella infection.

Development of effector responses against Salmonella

Despite the fact that Salmonella is an intracellular pathogen, the development of robust protective immunity requires the coordinated activity of B cells and T cells in susceptible mice (114). In this model, CD4 T cells play a critical role in clearing primary Salmonella infection and are also required for acquired resistance to secondary infection (115–117). In contrast, B cells are dispensable for resolving primary Salmonella infection but are required for protection against secondary challenge (118–120).

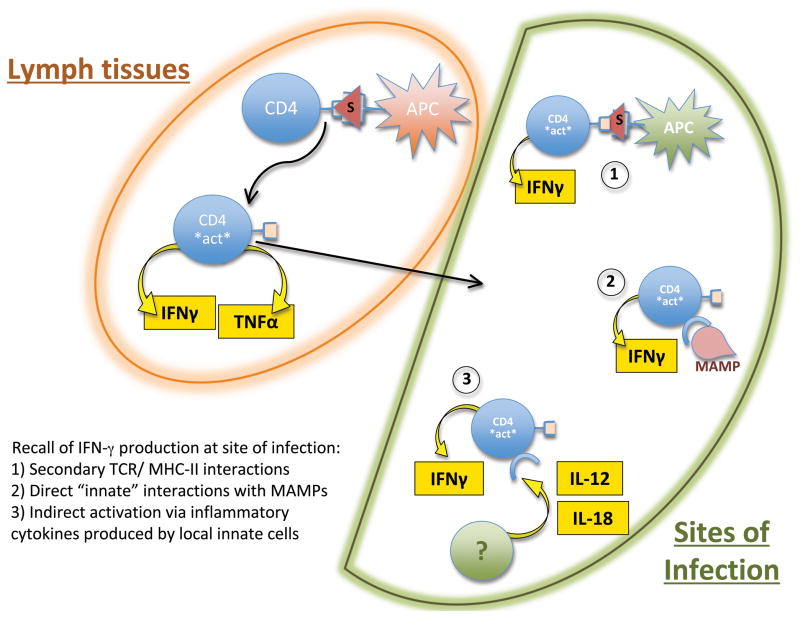

CD4 T cells

The development of Salmonella-specific CD4 effector responses has been examined in both susceptible and resistant mice. Together, these studies suggest massive expansion of Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells and rapid acquisition of Th1 effector functions, namely the enhanced ability to secrete IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 upon restimulation (121–123). These activated Th1 cells can be clearly detected around one week after Salmonella infection (122), consistent with the rapid tempo of CD4 T cell activation described in studies above. Optimal expansion of these Th1 cells has been shown to require expression of both PD-L1 and the TNFR family members OX40 and CD30 (124, 125), although the timing and context where these particular signals are delivered is not yet clear. Appropriately activated Th1 cells will continue to expand and can eventually comprise around 50% of all CD4 T cells around 2–3 weeks after infection (122). Furthermore, these effector Th1 cells acquire the capability to rapidly secrete cytokines in response to innate signals such as LPS (126), although it is not clear whether T cells respond directly or indirectly to this inflammatory stimulus. This innate activation is unexpected since effector Th1 cells are normally thought to be stimulated to produce effector cytokines only after recognition of cognate peptide and MHC (127). A similar capacity to respond to innate stimuli has been reported for activated CD8 T cells during viral infection and has been shown to involve increased sensitivity to local IL-12 and IL-18 (128, 129). This innate immune responsiveness of Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells suggests a means by which the host can rapidly produce IFN-γ to activate macrophages within an infected tissue, even if bacteria are capable of inhibiting antigen presentation by infected phagocytes (130–132) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells acquire the capacity to produce IFN-γ in response to various stimuli.

Salmonella infection induces the expansion of antigen-specific CD4 T cells in secondary lymphoid tissues. These activated CD4 T cells acquire the ability to home to sites of infection and produce IFN-γ in order to activate infected macrophages. Restimulation of these activated (CD11aHI) Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells can occur (1) following ligation of the TCR, or can be initiated by bacterial products such as LPS. It is not yet clear whether this involves (2) direct recognition of PAMPs by activated T cells or (3) a response to inflammatory mediators such as IL-12 and IL-18.

However, despite the rapid and efficient development of a large number of CD4 Th1 effector cells during primary Salmonella infection, there is actually very little evidence that they contribute to bacterial clearance at this early stage of infection. Thus, mice that completely lack all CD4 or CD4 Th1 cells will only display enhanced bacterial growth around 3 weeks after infection (117, 133), indicating that Th1 cells do very little to regulate bacterial growth before this point. This confusing finding can be explained by active inhibition of the early Th1 effector response by replicating bacteria in vivo. It is important to emphasize that this inhibitory effect is on expanded effector Th1 cells rather than an effect on the initial activation of naive T cells. Although many in vitro studies would point to an inhibitory effect of Salmonella on antigen presentation to naive T cells in vitro (130, 134–136), this does not appear to affect Salmonella-specific CD4 expansion in vivo (49, 122, 137). In contrast, the gradual loss of effector CD4 T cells has been detected in Salmonella-infected mice in a process that required the presence of live bacteria and the expression of SPI-2 genes (138). Therefore, even though a large population of Salmonella-specific Th1 cells is generated very early after infection with Salmonella, the effector function of these cells is actively and specifically inhibited by replicating bacteria.

Treg and Th17 cells

Although many studies have demonstrated the importance of Th1 cells in protective immunity to Salmonella (133, 139, 140), recent studies also suggest a contribution by other effector CD4 subsets including regulatory T cells (Tregs) and Th17 cells. Tregs are able to suppress effector T cell responses and either arise from the thymus or develop after activation of naïve T cells in the presence of TGF-β (141). In contrast, Th17 cells arise after stimulation of naïve CD4 T cells in the presence of IL-6 and TGF-β and are important in mediating immunity to extracellular bacterial infections (142, 143). A recent study examined the development of Th1 cells and Tregs after Salmonella infection of resistant mice and found that alterations in the potency of Tregs during infection reduced the effectiveness of Th1 responses and increased bacterial growth (123). It is not yet clear whether similar alterations in Treg potency can affect the function of Th1 responses in the susceptible mouse model or in humans.

After oral infection with Salmonella, cytokines associated with Th17 cells, IL-17 and IL-22, are rapidly produced within the intestinal mucosa (144, 145). In these studies IL-17 and IL-22 production is induced by innate responses to bacterial infection rather than Th17 cells, however, they still indicate the potential for Th17 cytokines to participate in intestinal defense against Salmonella. Indeed, IL-17-deficient mice were reported to develop increased bacterial loads in systemic tissues compared to wild-type control mice (146). In a subsequent study IL-23-dependent production of IL-22, rather than IL-17, was found to contribute to bacterial clearance in vivo (147). Together, these studies suggest an important additional contribution of Th17 cells to protection against Salmonella infection. A Th17 response might be protective by initiating or enhancing neutrophil infiltration to intestinal tissues. Indeed, it was found that IL-17-deficient mice exhibited a defect in the ability to recruit neutrophils to sites of infection during Salmonella infection (145). Interestingly, highly susceptible SIV-infected macaques were found to have a deficiency in IL-17 and IL-22, but not IFN-γ (145), perhaps indicating that Th17 cells represent an important effector cell population particularly in the intestinal mucosa. In addition to neutrophil recruitment, Th17 cytokines induce production of antimicrobial peptides by epithelial cells that are effective against lumenal bacteria (9). Indeed, during Salmonella infection of rhesus macaques, IL-22 was important in the production of lipocalin-2, which prevents iron acquisition by bacteria (148). In summary, recent data suggest an additional role for Th17 cells in defense against Salmonella in the intestine and a role for Tregs in modulating the potency of Salmonella-specific Th1 cells in vivo. Greater study of each of these T helper populations in the mouse model of Salmonella infection and in human Salmonellosis is warranted.

Protective antibody response against Salmonella

As noted above, there is good evidence from human infections and the mouse model that Salmonella-specific B cell responses can contribute to bacterial clearance (38, 118, 119). However, the mechanism by which B cells contribute to protective immunity against Salmonella remains unclear.

Although Salmonella are generally found within SCVs in phagocytic cells, there is a short period during the infection cycle when bacteria are expected to be extracellular. Salmonella are tightly associated with mononuclear phagocytes in vivo (69, 84, 85), but also induce these infected cells to undergo apoptosis (54). Following this cell death, bacteria are presumably found in the extracellular compartment before infecting a neighboring phagocyte. It is therefore possible that antibody has direct access to Salmonella during this short period of time and prevents cell-to-cell transmission (108). Indeed, opsonization of bacteria with Salmonella-specific antibody impeded bacterial colonization in vivo (149). Antibody has also been suggested to play an important role in amplifying the processing and presentation of Salmonella antigens to CD4 T cells, thus affecting the quantity and quality of the Th1 response (150, 151). Innate B cell responses to TLR ligands have also been shown to be important for the development of Th1 responses in vivo (152, 153), suggesting another route by which effector T cell development can be regulated by B cell responses to Salmonella. However, recent work suggests that B cell signaling via MyD88 can also suppress the development of protective immunity during Salmonella infection (154). Thus, the role of innate immune signaling in B cells serves an important regulatory function but requires further analysis. The presence of Salmonella-specific IgA in the intestinal mucosa may also prevent or reduce bacterial penetration of the intestinal barrier (155). It is not yet clear which of these mechanisms makes the greatest contribution to protective immunity to Salmonella infection but an important role for antibody is also suggested from human studies (156). Although the specificity of these antibody responses are mostly undefined, antibodies specific for the LPS O-antigen, flagellin, the ViCPS antigen, and OmpD are all thought to be protective (114, 157).

Concluding remarks

Immunologists and microbiologists have long appreciated murine infection with Salmonella as a model that allows a natural route of challenge and detailed study of bacterial virulence factors and innate and adaptive immunity. The powerful genetic and immunological tools that are available in this model make it ideal for dissecting the complicated issues of bacterial pathogenesis and immunity to infection. Despite the uncertainty of translating murine data to human typhoid or NTS, it is likely that each of these infections has similar immunological aspects since all three involve disseminated Salmonellosis. Bacterial entry is a complex process involving the interaction of bacterial SPI-1 gene products with M cells overlying Peyer’s patches and SILTs. Recent data suggest that protective immunity requires coordinated interaction of Salmonella-specific Th1 and Th17 cells and the activation of Salmonella-specific B cells. Interestingly, this combined requirement bears many similarities to data examining the dissemination of NTS in humans. Greater study of the immune parameters associated with protection in the mouse model is therefore likely to inform the generation of new vaccines against disseminated Salmonella infections in humans.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Sing-Sing Way, Adam Cunningham, and Oliver Pabst for critical reading of the manuscript and numerous helpful suggestions. We would also like to thank Ms. Hope O’Donnell for designing and preparing Figure 3. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to SJM (AI055743 and AI56172).

References

- 1.Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:607–625. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine MM. Enteric infections and the vaccines to counter them: future directions. Vaccine. 2006;24:3865–3873. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crump JA, Mintz ED. Global trends in typhoid and paratyphoid Fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:241–246. doi: 10.1086/649541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter PB, Collins FM. The route of enteric infection in normal mice. J Exp Med. 1974;139:1189–1203. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.5.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zinkernagel RM. Cell-mediated immune response to Salmonella typhimurium infection in mice: development of nonspecific bactericidal activity against Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1976;13:1069–1073. doi: 10.1128/iai.13.4.1069-1073.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittrucker HW, Kaufmann SH. Immune response to infection with Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:457–463. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mastroeni P, Chabalgoity JA, Dunstan SJ, Maskell DJ, Dougan G. Salmonella: immune responses and vaccines. Vet J. 2001;161:132–164. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.2000.0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monack DM, Mueller A, Falkow S. Persistent bacterial infections: the interface of the pathogen and the host immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:747–765. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos RL, Raffatellu M, Bevins CL, Adams LG, Tukel C, Tsolis RM, Baumler AJ. Life in the inflamed intestine, Salmonella style. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews-Polymenis HL, Baumler AJ, McCormick BA, Fang FC. Taming the elephant: Salmonella biology, pathogenesis, and prevention. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2356–2369. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00096-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parry CM, Hien TT, Dougan G, White NJ, Farrar JJ. Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1770–1782. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Multistate outbreaks of Salmonella infections associated with raw tomatoes eaten in restaurants--United States, 2005–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:909–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Outbreak of Salmonella serotype Saintpaul infections associated with multiple raw produce items--United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:929–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Multistate outbreak of Salmonella infections associated with peanut butter and peanut butter-containing products--United States, 2008–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen SJ, MacKinnon LC, Goulding JS, Bean NH, Slutsker L. Surveillance for foodborne-disease outbreaks--United States, 1993–1997. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 2000;49:1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyachuba DG. Foodborne illness: is it on the rise? Nutr Rev. 2010;68:257–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crump JA, Luby SP, Mintz ED. The global burden of typhoid fever. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:346–353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clasen T, Schmidt WP, Rabie T, Roberts I, Cairncross S. Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2007;334:782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39118.489931.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mara DD. Water, sanitation and hygiene for the health of developing nations. Public Health. 2003;117:452–456. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser A, Paul M, Goldberg E, Acosta CJ, Leibovici L. Typhoid fever vaccines: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Vaccine. 2007;25:7848–7857. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhan MK, Bahl R, Bhatnagar S. Typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Lancet. 2005;366:749–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gotuzzo E, Morris JG, Jr, Benavente L, Wood PK, Levine O, Black RE, Levine MM. Association between specific plasmids and relapse in typhoid fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1779–1781. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.9.1779-1781.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yew FS, Chew SK, Goh KT, Monteiro EH, Lim YS. Typhoid fever in Singapore: a review of 370 cases. J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;94:352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MD, Duong NM, Hoa NT, Wain J, Ha HD, Diep TS, Day NP, Hien TT, White NJ. Comparison of ofloxacin and ceftriaxone for short-course treatment of enteric fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1716–1720. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wain J, Hien TT, Connerton P, Ali T, Parry CM, Chinh NT, Vinh H, Phuong CX, Ho VA, Diep TS, Farrar JJ, White NJ, Dougan G. Molecular typing of multiple-antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi from Vietnam: application to acute and relapse cases of typhoid fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2466–2472. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2466-2472.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monack DM, Bouley DM, Falkow S. Salmonella typhimurium persists within macrophages in the mesenteric lymph nodes of chronically infected Nramp1+/+ mice and can be reactivated by IFNgamma neutralization. J Exp Med. 2004;199:231–241. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford RW, Rosales-Reyes R, Ramirez-Aguilarde LM, Chapa-Azuela O, Alpuche-Aranda C, Gunn JS. Gallstones play a significant role in Salmonella spp. gallbladder colonization and carriage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4353–4358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000862107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin A, Baraho-Hassan D, McSorley SJ. Successful treatment of bacterial infection hinders development of acquired immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183:1263–1270. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon MA. Salmonella infections in immunocompromised adults. J Infect. 2008;56:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham SM, Molyneux EM, Walsh AL, Cheesbrough JS, Molyneux ME, Hart CA. Nontyphoidal Salmonella infections of children in tropical Africa. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1189–1196. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200012000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brent AJ, Oundo JO, Mwangi I, Ochola L, Lowe B, Berkley JA. Salmonella bacteremia in Kenyan children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:230–236. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000202066.02212.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kariuki S, Revathi G, Gakuya F, Yamo V, Muyodi J, Hart CA. Lack of clonal relationship between non-typhi Salmonella strain types from humans and those isolated from animals living in close contact. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;33:165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, Kariuki S, Holt KE, Gordon MA, Harris D, Clarke L, Whitehead S, Sangal V, Marsh K, Achtman M, Molyneux ME, Cormican M, Parkhill J, MacLennan CA, Heyderman RS, Dougan G. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res. 2009;19:2279–2287. doi: 10.1101/gr.091017.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chierakul W, Rajanuwong A, Wuthiekanun V, Teerawattanasook N, Gasiprong M, Simpson A, Chaowagul W, White NJ. The changing pattern of bloodstream infections associated with the rise in HIV prevalence in northeastern Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98:678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters RP, Zijlstra EE, Schijffelen MJ, Walsh AL, Joaki G, Kumwenda JJ, Kublin JG, Molyneux ME, Lewis DK. A prospective study of bloodstream infections as cause of fever in Malawi: clinical predictors and implications for management. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:928–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon MA, Kankwatira AM, Mwafulirwa G, Walsh AL, Hopkins MJ, Parry CM, Faragher EB, Zijlstra EE, Heyderman RS, Molyneux ME. Invasive non-typhoid salmonellae establish systemic intracellular infection in HIV-infected adults: an emerging disease pathogenesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:953–962. doi: 10.1086/651080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Vosse E, Ottenhoff TH. Human host genetic factors in mycobacterial and Salmonella infection: lessons from single gene disorders in IL-12/IL-23-dependent signaling that affect innate and adaptive immunity. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacLennan CA, Gondwe EN, Msefula CL, Kingsley RA, Thomson NR, White SA, Goodall M, Pickard DJ, Graham SM, Dougan G, Hart CA, Molyneux ME, Drayson MT. The neglected role of antibody in protection against bacteremia caused by nontyphoidal strains of Salmonella in African children. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1553–1562. doi: 10.1172/JCI33998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santos RL, Zhang S, Tsolis RM, Kingsley RA, Adams LG, Baumler AJ. Animal models of salmonella infections: enteritis versus typhoid fever. Micrtobes Infect. 2001;3:1335–1344. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barthel M, Hapfelmeier S, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kremer M, Rohde M, Hogardt M, Pfeffer K, Russmann H, Hardt WD. Pretreatment of mice with streptomycin provides a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis model that allows analysis of both pathogen and host. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2839–2858. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2839-2858.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hapfelmeier S, Hardt WD. A mouse model for S. typhimurium-induced enterocolitis. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasetti MF, Levine MM, Sztein MB. Animal models paving the way for clinical trials of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi live oral vaccines and live vectors. Vaccine. 2003;21:401–418. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galan JE, Curtiss R., 3rd Cloning and molecular characterization of genes whose products allow Salmonella typhimurium to penetrate tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6383–6387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fierer J, Guiney DG. Diverse virulence traits underlying different clinical outcomes of Salmonella infection. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:775–780. doi: 10.1172/JCI12561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McSorley SJ, Xu D, Liew FY. Vaccine efficacy of Salmonella strains expressing glycoprotein 63 with different promoters. Infect Immun. 1997;65:171–178. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.171-178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones BD, Ghori N, Falkow S. Salmonella typhimurium initiates murine infection by penetrating and destroying the specialized epithelial M cells of the Peyer’s patches. J Exp Med. 1994;180:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hohmann AW, Schmidt G, Rowley D. Intestinal colonization and virulence of Salmonella in mice. Infect Immun. 1978;22:763–770. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.3.763-770.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McSorley SJ, Asch S, Costalonga M, Rieinhardt RL, Jenkins MK. Tracking Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells in vivo reveals a local mucosal response to a disseminated infection. Immunity. 2002;16:365–377. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Niess JH, Zammit DJ, Ravindran R, Srinivasan A, Maxwell JR, Stoklasek T, Yadav R, Williams IR, Gu X, McCormick BA, Pazos MA, Vella AT, Lefrancois L, Reinecker HC, McSorley SJ. CCR6-Mediated Dendritic Cell Activation of Pathogen-Specific T Cells in Peyer’s Patches. Immunity. 2006;24:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones BD, Falkow S. Salmonellosis: host immune responses and bacterial virulence determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Francis CL, Ryan TA, Jones BD, Smith SJ, Falkow S. Ruffles induced by Salmonella and other stimuli direct macropinocytosis of bacteria. Nature. 1993;364:639–642. doi: 10.1038/364639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Heffron F. The lpf fimbrial operon mediates adhesion of Salmonella typhimurium to murine Peyer’s patches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:279–283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hase K, Kawano K, Nochi T, Pontes GS, Fukuda S, Ebisawa M, Kadokura K, Tobe T, Fujimura Y, Kawano S, Yabashi A, Waguri S, Nakato G, Kimura S, Murakami T, Iimura M, Hamura K, Fukuoka S, Lowe AW, Itoh K, Kiyono H, Ohno H. Uptake through glycoprotein 2 of FimH(+) bacteria by M cells initiates mucosal immune response. Nature. 2009;462:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature08529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Velden AW, Velasquez M, Starnbach MN. Salmonella rapidly kill dendritic cells via a caspase-1-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;171:6742–6749. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fink SL, Cookson BT. Apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necrosis: mechanistic description of dead and dying eukaryotic cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1907–1916. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.1907-1916.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Yu JW, Datta P, Miller B, Jankowski W, Rosenberg S, Zhang J, Alnemri ES. The pyroptosome: a supramolecular assembly of ASC dimers mediating inflammatory cell death via caspase-1 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1590–1604. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monack DM, Hersh D, Ghori N, Bouley D, Zychlinsky A, Falkow S. Salmonella exploits caspase-1 to colonize Peyer’s patches in a murine typhoid model. J Exp Med. 2000;192:249–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamada H, Hiroi T, Nishiyama Y, Takahashi H, Masunaga Y, Hachimura S, Kaminogawa S, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Iwanaga T, Kiyono H, Yamamoto H, Ishikawa H. Identification of multiple isolated lymphoid follicles on the antimesenteric wall of the mouse small intestine. J Immunol. 2002;168:57–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pabst O, Herbrand H, Friedrichsen M, Velaga S, Dorsch M, Berhardt G, Worbs T, Macpherson AJ, Forster R. Adaptation of solitary intestinal lymphoid tissue in response to microbiota and chemokine receptor CCR7 signaling. J Immunol. 2006;177:6824–6832. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Halle S, Bumann D, Herbrand H, Willer Y, Dahne S, Forster R, Pabst O. Solitary intestinal lymphoid tissue provides a productive port of entry for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1577–1585. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herbrand H, Bernhardt G, Forster R, Pabst O. Dynamics and function of solitary intestinal lymphoid tissue. Crit Rev Immunol. 2008;28:1–13. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v28.i1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kraus MD, Amatya B, Kimula Y. Histopathology of typhoid enteritis: morphologic and immunophenotypic findings. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:949–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jang MH, Kweon MN, Iwatani K, Yamamoto M, Terahara K, Sasakawa C, Suzuki T, Nochi T, Yokota Y, Rennert PD, Hiroi T, Tamagawa H, Iijima H, Kunisawa J, Yuki Y, Kiyono H. Intestinal villous M cells: an antigen entry site in the mucosal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6110–6115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400969101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martinoli C, Chiavelli A, Rescigno M. Entry route of Salmonella typhimurium directs the type of induced immune response. Immunity. 2007;27:975–984. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Niess JH, Reinecker HC. Dendritic cells in the recognition of intestinal microbiota. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:558–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schulz O, Jaensson E, Persson EK, Liu X, Worbs T, Agace WW, Pabst O. Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3101–3114. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Persson EK, Jaensson E, Agace WW. The diverse ontogeny and function of murine small intestinal dendritic cell/macrophage subsets. Immunobiology. 2010;215:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pabst O, Bernhardt G. The puzzle of intestinal lamina propria dendritic cells and macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2107–2111. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Baumler AJ, Falkow S, Valdivia R, Brown W, Le M, Berggren R, Parks WT, Fang FC. Extraintestinal dissemination of Salmonella by CD18-expressing phagocytes. Nature. 1999;401:804–808. doi: 10.1038/44593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gerichter CB. The dissemination of Salmonella typhi, S. paratyphi A and S. paratyphi B through the organs of the white mouse by oral infection. J Hyg (Lond) 1960;58:307–319. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400038420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Worley MJ, Nieman GS, Geddes K, Heffron F. Salmonella typhimurium disseminates within its host by manipulating the motility of infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17915–17920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604054103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R, Granucci F, Kraehenbuhl JP, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:361–367. doi: 10.1038/86373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Niess JH, Brand S, Gu X, Landsman L, Jung S, McCormick BA, Vyas JM, Boes M, Ploegh HL, Fox JG, Littman DR, Reinecker HC. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science. 2005;307:254–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1102901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chieppa M, Rescigno M, Huang AY, Germain RN. Dynamic imaging of dendritic cell extension into the small bowel lumen in response to epithelial cell TLR engagement. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2841–2852. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vallon-Eberhard A, Landsman L, Yogev N, Verrier B, Jung S. Transepithelial pathogen uptake into the small intestinal lamina propria. J Immunol. 2006;176:2465–2469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iwasaki A, Kelsall BL. Localization of distinct Peyer’s patch dendritic cell subsets and their recruitment by chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3alpha, MIP-3beta, and secondary lymphoid organ chemokine. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1381–1394. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tam MA, Rydstrom A, Sundquist M, Wick MJ. Early cellular responses to Salmonella infection: dendritic cells, monocytes, and more. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:140–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moon JJ, McSorley SJ. Tracking the dynamics of salmonella specific T cell responses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;334:179–198. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-93864-4_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Voedisch S, Koenecke C, David S, Herbrand H, Forster R, Rhen M, Pabst O. Mesenteric lymph nodes confine dendritic cell-mediated dissemination of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and limit systemic disease in mice. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3170–3180. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00272-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bonneau M, Epardaud M, Payot F, Niborski V, Thoulouze MI, Bernex F, Charley B, Riffault S, Guilloteau LA, Schwartz-Cornil I. Migratory monocytes and granulocytes are major lymphatic carriers of Salmonella from tissue to draining lymph node. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:268–276. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jackson A, Nanton MR, O’Donnell H, Akue AD, McSorley SJ. Innate Immune Activation during Salmonella Infection Initiates Extramedullary Erythropoiesis and Splenomegaly. J Immunol. 2010;185:6198–6204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Low KB, Ittensohn M, Le T, Platt J, Sodi S, Amoss M, Ash O, Carmichael E, Chakraborty A, Fischer J, Lin SL, Luo X, Miller SI, Zheng L, King I, Pawelek JM, Bermudes D. Lipid A mutant Salmonella with suppressed virulence and TNFalpha induction retain tumor-targeting in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:37–41. doi: 10.1038/5205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu YA, Shabahang S, Timiryasova TM, Zhang Q, Beltz R, Gentschev I, Goebel W, Szalay AA. Visualization of tumors and metastases in live animals with bacteria and vaccinia virus encoding light-emitting proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:313–320. doi: 10.1038/nbt937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sheppard M, Webb C, Heath F, Mallows V, Emilianus R, Maskell D, Mastroeni P. Dynamics of bacterial growth and distribution within the liver during Salmonella infection. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:593–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Richter-Dahlfors A, Buchan AM, Finlay BB. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;186:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Mastroeni P, Ischiropoulos H, Fang FC. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. I. Effects on microbial killing by activated peritoneal macrophages in vitro. J Exp Med. 2000;192:227–236. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mastroeni P, Vazquez-Torres A, Fang FC, Xu Y, Khan S, Hormaeche CE, Dougan G. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. II. Effects on microbial proliferation and host survival in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:237–248. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chakravortty D, Hansen-Wester I, Hensel M. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 mediates protection of intracellular Salmonella from reactive nitrogen intermediates. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1155–1166. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Miller SI. PhoP/PhoQ: macrophage-specific modulators of Salmonella virulence? Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2073–2078. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Garvis SG, Beuzon CR, Holden DW. A role for the PhoP/Q regulon in inhibition of fusion between lysosomes and Salmonella-containing vacuoles in macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:731–744. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.White JK, Mastroeni P, Popoff JF, Evans CA, Blackwell JM. Slc11a1-mediated resistance to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Leishmania donovani infections does not require functional inducible nitric oxide synthase or phagocyte oxidase activity. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:311–320. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fields PI, Swanson RV, Haidaris CG, Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rydstrom A, Wick MJ. Monocyte recruitment, activation, and function in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue during oral Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 2007;178:5789–5801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Noriega LM, Van der Auwera P, Daneau D, Meunier F, Aoun M. Salmonella infections in a cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 1994;2:116–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00572093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tumbarello M, Tacconelli E, Caponera S, Cauda R, Ortona L. The impact of bacteraemia on HIV infection. Nine years experience in a large Italian university hospital. J Infect. 1995;31:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(95)92110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Conlan JW. Neutrophils prevent extracellular colonization of the liver microvasculature by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1043–1047. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.1043-1047.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rydstrom A, Wick MJ. Monocyte and neutrophil recruitment during oral Salmonella infection is driven by MyD88-derived chemokines. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3019–3030. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and their ligands. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;270:81–92. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59430-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Franchi L, Amer A, Body-Malapel M, Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Jagirdar R, Inohara N, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, Grant EP, Nunez G. Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase-1 and interleukin 1beta in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:576–582. doi: 10.1038/ni1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miao EA, Alpuche-Aranda CM, Dors M, Clark AE, Bader MW, Miller SI, Aderem A. Cytoplasmic flagellin activates caspase-1 and secretion of interleukin 1beta via Ipaf. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:569–575. doi: 10.1038/ni1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Winter SE, Thiennimitr P, Nuccio SP, Haneda T, Winter MG, Wilson RP, Russell JM, Henry T, Tran QT, Lawhon SD, Gomez G, Bevins CL, Russmann H, Monack DM, Adams LG, Baumler AJ. Contribution of flagellin pattern recognition to intestinal inflammation during Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1904–1916. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01341-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Broz P, Newton K, Lamkanfi M, Mariathasan S, Dixit VM, Monack DM. Redundant roles for inflammasome receptors NLRP3 and NLRC4 in host defense against Salmonella. J Exp Med. 207:1745–1755. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McSorley SJ, Ehst BD, Yu Y, Gewirtz AT. Bacterial flagellin is an effective adjuvant for CD4 T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2002;169:3914. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Srinivasan A, Griffin A, Muralimohan G, Ertelt JM, Ravindran R, Vella AT, McSorley SJ. Salmonella flagellin induces bystander activation of splenic dendritic cells and hinders bacterial replication in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:6169–6175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sierro F, Dubois B, Coste A, Kaiserlian D, Kraehenbuhl JP, Sirard JC. Flagellin stimulation of intestinal epithelial cells triggers CCL20-mediated migration of dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13722–13727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241308598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Moon JJ, Chu HH, Pepper M, McSorley SJ, Jameson SC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK. Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity. 2007;27:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bumann D. In vivo visualization of bacterial colonization, antigen expression and specific T-cell induction following oral administration of live recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4618–4626. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4618-4626.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ravindran R, McSorley SJ. Tracking the dynamics of T-cell activation in response to Salmonella infection. Immunology. 2005;114:450–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.McSorley SJ, Cookson BT, Jenkins MK. Characterization of CD4+ T cell responses during natural infection with Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol. 2000;164:986–993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, Hawn TR, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Eng JK, Akira S, Underhill DM, Aderem A. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Srinivasan A, McSorley SJ. Activation of Salmonella-specific immune responses in the intestinal mucosa. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2006;54:25–31. doi: 10.1007/s00005-006-0003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Srinivasan A, McSorley SJ. Visualizing the immune response to pathogens. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:494–498. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nix RN, Altschuler SE, Henson PM, Detweiler CS. Hemophagocytic macrophages harbor Salmonella enterica during persistent infection. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e193. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mastroeni P. Immunity to systemic Salmonella infections. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:393–406. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nauciel C. Role of CD4+ T cells and T-independent mechanisms in aquired resistance to Salmonella typhimurium infection. J Immunol. 1990;145:1265–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sinha K, Mastroeni P, Harrison J, de Hormaeche RD, Hormaeche CE. Salmonella typhimurium aroA, htrA, and AroD htrA mutants cause progressive infections in athymic (nu/nu) BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1566–1569. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1566-1569.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hess J, Ladel C, Miko D, Kaufmann SH. Salmonella typhimurium aroA-infection in gene-targeted immunodeficient mice: major role of CD4+ TCR-alpha beta cells and IFN-gamma in bacterial clearance independent of intracellular location. J Immunol. 1996;156:3321–3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mastroeni P, Simmons C, Fowler R, Hormaeche CE, Dougan G. Igh-6(−/−) (B-cell-deficient) mice fail to mount solid aquired resistance to oral challenge with virulent Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and show impaired Th1 T-cell responses to Salmonella antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68:46–53. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.46-53.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.McSorley SJ, Jenkins MK. Antibody is required for protection against virulent but not attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3344–3348. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3344-3348.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mittrucker HW, Raupach B, Kohler A, Kaufmann SH. Cutting edge: role of B lymphocytes in protective immunity against Salmonella typhimurium infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:1648–1652. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mittrucker H, Kohler A, Kaufmann SH. Characterization of the murine T-lymphocyte response to salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:199–203. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.199-203.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Srinivasan A, Foley J, McSorley SJ. Massive Number of Antigen-Specific CD4 T Cells during Vaccination with Live Attenuated Salmonella Causes Interclonal Competition. J Immunol. 2004;172:6884–6893. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Johanns TM, Ertelt JM, Rowe JH, Way SS. Regulatory T cell suppressive potency dictates the balance between bacterial proliferation and clearance during persistent Salmonella infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gaspal F, Bekiaris V, Kim MY, Withers DR, Bobat S, MacLennan IC, Anderson G, Lane PJ, Cunningham AF. Critical synergy of CD30 and OX40 signals in CD4 T cell homeostasis and Th1 immunity to Salmonella. J Immunol. 2008;180:2824–2829. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]