The Calgary Health Region, with its approximately 22 000 employees and 2200 physician partners, is no stranger to controversy. In January 2001, a young man who walked out of 2 busy emergency departments in the city before being treated was the subject of an internal review after he travelled to a nearby town where he was operated on, developed bronchospasm and died. An inquiry into his death criticized the Calgary Health Region for not being forthcoming; a media frenzy ensued, resulting in a loss of credibility for the Region both clinically and administratively.

Against this backdrop, the finding of unexplained hyperkalemia in March 2004 in an elderly patient undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy with continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) (citrate anticoagulation) in the cardiovascular intensive care unit (ICU) at Foothills Medical Centre led to an analysis of the dialysate solution. The solution was found to contain 5.9 mmol/L sodium (should have been 110 mmol/L) and 53.6 mmol/L potassium (should have been zero). Immediate action by the attending intensivist resulted in the removal of all bags of the dialysate solution from ICUs across the Region. A subsequent review of other recent deaths suggested that approximately 1 week earlier a male patient with significant acidosis as a result of intestinal ischemia had died with hyperkalemia, also while undergoing continuous renal replacement in the main ICU. At the time of his death, hyperkalemia had been attributed to profound acidosis and tissue necrosis.

The Regional Critical Incident Review process was instituted immediately. The review showed that the error had occurred in our Central Production Pharmacy. Within the Calgary Health Region, there is a single large pharmacy in an offsite location to support the 4 acute care hospitals. This facility is separate from the site hospitals; however, it is operated by Regional Pharmacy Services. Staff had inadvertently taken potassium chloride (KCl) instead of sodium chloride (NaCl) for the preparation of a batch of dialysis solution. The carton of the concentrated KCl looked very similar to that of the NaCl and was located on the opposite side of the aisle. The 250-mL bottles of KCl and NaCl also looked very much alike; they were identical in size and shape and had similar labelling, although there was a black cap on the KCl bottle (see Figure). This error went undetected through a 4-check process. All the dialysis bags of the same batch were accounted for within 24 hours of the incident coming to light, and warning labels were applied to the KCl bottles immediately. A change of supplier for the concentrated NaCl solution was also planned and instituted.

Figure 1. Sodium chloride and potassium chloride bottles: a dangerous similarity Photo: Courtesy Calgary Health Region

Once the immediate safety issue has been addressed, the challenge was to respond appropriately to the tragedy from a communications perspective. The regional executive agreed that there must be public disclosure. This was felt to be necessary in light of the previous criticism of the Region, but it was also a deliberate effort to act in the manner that the Region was asking of staff: i.e., to fully disclose medical errors to the public and to other health care providers in order to support system change and reduce the likelihood of similar events occurring again. Public disclosure of the events at Foothills and the Central Production Pharmacy was supported by corporate counsel and the Region's insurer. The timing of the disclosure was balanced with a duty to inform and support the families affected, and to gather enough information from the investigation to provide a correct preliminary conclusion as to what had gone wrong. One family had been notified at the time of the original incident (the index case). The minister of health and wellness was fully briefed just before the public announcement.

In our view, a strategy of honesty and sincerity should never be questioned. The decision to report publicly was correct. The media in general have been quite balanced in their coverage, with several writers and commentators even being very supportive with respect to our process of error recognition and reporting. What was less expected by the clinicians involved was the length of time the story stayed active in the Calgary media.

In addition, we did not predict certain aspects of the ongoing public and media response, namely:

1. confusion over the type of dialysis involved

2. the belief of some patients that they had had equivalent experiences with potassium (none had in fact been similarly treated)

3. references to previous, unrelated, negative experiences with the health care system

4. a debate regarding culpability and human resources implications of those immediately involved in the incident.

The families affected by these tragic errors have been extremely supportive and understanding, affirming our approach to dealing with the tragedy. That said, we have of course learned a great deal from this experience (see Text Box). We have grieved, but we have also grown. We owe it to the families of the victims to translate our words about patient safety into actions.

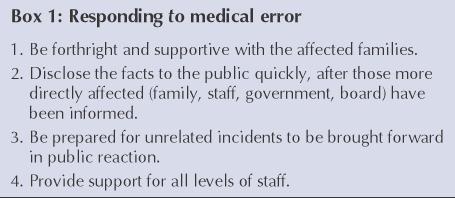

Box 1.

Robert V. Johnston Paul Boiteau Kelley Charlebois Steve Long Calgary Health Region Calgary, Alta. David U Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada Sunnybrook and Women's College Health Sciences Centre Toronto, Ont.