Abstract

Aberrations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors frequently affect the activity of critical signal transduction pathways. To analyze systematically the relationship between the activation status of protein networks and other characteristics of cancer cells, we performed reverse phase protein array (RPPA) profiling of the NCI60 cell lines for total protein expression and activation-specific markers of critical signaling pathways. To extend the scope of the study, we merged those data with previously published RPPA results for the NCI60. Integrative analysis of the expanded RPPA data set revealed 5 major clusters of cell lines and 5 principal proteomic signatures. Comparison of mutations in the NCI60 cell lines with patterns of protein expression demonstrated significant associations for PTEN, PIK3CA, BRAF and APC mutations with proteomic clusters. PIK3CA and PTEN mutation enrichment were not cell lineage-specific but were associated with dominant yet distinct groups of proteins. The five RPPA-defined clusters were strongly associated with sensitivity to standard anti-cancer agents. RPPA analysis identified 27 protein features significantly associated with sensitivity to paclitaxel. The functional status of those proteins was interrogated in a paclitaxel whole genome siRNA library synthetic lethality screen, and confirmed the predicted associations with drug sensitivity. These studies expand our understanding of the activation status of protein networks in the NCI60 cancer cell lines, demonstrate the importance of the direct study of protein expression and activation, and provide a basis for further studies integrating the information with other molecular and pharmacological characteristics of cancer.

Keywords: NCI60, reverse phase protein arrays, signal transduction

Introduction

The NCI60 cell line collection is the most extensively characterized panel of cancer cell lines in existence. It consists of 60 human cancer cell lines derived from nine different tumor types, including leukemia (LN), colon (CO), lung (NSCLC), central nervous system (CNS), renal (REN), melanoma (ME), ovarian (OVR), breast (BR), and prostate (PRO) (1). In part because of the extensive pharmacological characterization of NCI60, they have frequently been used as test samples for emerging technologies and methods of analysis (2–8). Global gene expression patterns and alterations of DNA copy numbers in the NCI60 collection have been assessed by a number of microarray-based technologies and the resulting data sets have been pooled and analyzed together with pharmacological characteristics of the cell lines, providing a comprehensive interaction map between pharmacological and genetic characteristics of the cells (9–11).

Although those studies have yielded much useful information, there is a strong rationale for complementing them with a direct assessment of the expression and activation of proteins involved in critical signal transduction pathways. During the progression of cancer, many signaling proteins are activated through genetic, epigenetic and post-translational events. Approaches based on gene expression signatures have been used to interrogate gain-of-function or loss-of-function events during tumor progression (12, 13), but such analyses cannot assess translational regulation. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated frequent and marked discordance between mRNA expression levels and protein levels in tumors and cell lines (14–17). Moreover, kinase signaling pathways are generally regulated by post-translational modifications, particularly phosphorylation events. Direct examination of the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of signaling proteins should improve our understanding of the molecular and pharmacologic characteristics of the NCI60 cell lines.

The reverse phase protein array (RPPA) is a powerful technology that provides quantitative measurement of protein expression and activation. Previously RPPA was used to profile the expression of 94 proteins in the NCI60 cell line collection (14, 18) . Although that study provided a number of interesting findings, insight into the role of signaling networks was critically limited by the lack of antibodies that recognize activation-specific modifications of proteins. We have developed RPPA assays to assess post-translational modifications that reflect the activation status of many proteins involved in kinase signaling (19–22). Recently we used this technique to measure the levels of phosphorylated AKT (P-AKT) in the NCI60 cell lines, and found an unexpected difference in P-AKT levels in cell lines with PTEN loss as compared to those with PIK3CA mutations (22). Here we report the RPPA analysis of the NCI60 for an expanded panel of antibodies, including activation-specific markers of other signaling pathways and additional markers related to PI3K–AKT signaling. We merged these results with the existing RPPA data of the NCI60, and demonstrate a relatively high degree of reproducibility and correlation of overlapping antibodies between the data sets. The integrated RPPA data set was used to assess the association of tumor type with protein expression and activation, extending previous studies which did not include phospho-proteins (14, 18). We also performed the first systematic evaluation of protein features associated with the oncogenic mutations present in the NCI60 (23). Finally, we performed a pilot analysis to identify proteins that correlate with sensitivity to standard anti-cancer agents. The functional significance of proteins associated with taxol sensitivity was assessed by reviewing results of a paclitaxel whole-genome siRNA synthetic lethality screen, and validated the predictive nature of these associations.

Materials and Methods

Reverse Phase Protein Array Studies

Two independent data sets of RPPA data were generated. An initial analysis (MDA_Pilot) was performed by extracting proteins from cell pellets that were generated and provided by the NCI. A subsequent analysis (MDA_CLSS) was performed using viable cells were obtained from the NCI, that were grown in our laboratory. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, and proteins were harvested when the cells reached ~70% confluence. These cells, and the cell pellets provided by the NCI, were lysed with buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 50mM Hepes pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA, 100mM NaF, 10mM NaPPi, 10% glycerol, 1mM Na3VO4, and Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Protein supernatants were isolated using standard methods (22), and protein concentration was determined by BCA Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Samples were diluted to a uniform protein concentration, and then they were denatured in 1% SDS for 10 minutes at 95°C. Samples were stored at −80°C until use. RPPA analysis was performed as described previously (20–22). A logarithmic value reflecting the relative amount of each protein in each sample was generated for analyses. MDA_Pilot RPPA analysis was performed using a total of 34 antibodies, and the MDA_CLSS analysis used 99 antibodies [Table S1]. The RPPA data set “NCI” was previously reported (14), and the publicly-available data was downloaded from the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program website1. Each of the three RPPA data sets was independently normalized and mean-centered. The data sets were then merged into a single data set for subsequent analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using Cluster and Treeview2. The reproducibility and correlation of results were tested by calculating Pearson Correlation coefficients. The associations between protein features and mutation status within cell line clusters were determined by Chi-square and Fisher’s exact testing. Associations with drug sensitivity were assessed using the GI50 data for the NCI60 cell lines3 Analyses of statistical associations between drug sensitivity and RPPA clusters were performed by one-way ANOVA. Proteins significantly correlated with paclitaxel sensitivity were selected based on Pearson Correlation Coefficients (p<0.05 by the t-statistic). All statistical analyses were performed in the R language environment4.

Results

Integration and Analysis of RPPA Data Sets

Two new RPPA data sets for the NCI60 cell line set were generated. “MDA_PILOT” RPPA analysis was performed using cell lysates generated from cell pellets provided by the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program. That study included measurement of 34 protein features (Table S1). A second study, “MDA_CLSS,” was performed using cell lysates generated by independently growing the NCI60 cell lines in our laboratory using tissue culture conditions recommended by the NCI, with lysis of cells performed directly on tissue culture plates. The MDA_CLSS analysis included 99 protein features, 26 of which overlapped with those in the MDA_Pilot (Table S1; Figure S1A). A comparison of the two RPPA analyses demonstrated that 20/26 (76.9%) of the shared proteins had statistically significant, positive correlations (Figure S1B). Because those results supported the feasibility of merging independent RPPA data sets, and in order to maximize the strength of the proteomic analysis of the NCI60, the two data sets were integrated with previously-published RPPA data on the NCI60 for 94 proteins 5. Each data set was individually normalized and mean-centered prior to merging.

We first compared results for the three independent RPPA data sets. Five proteins (CTNNB1, CDH1, ESR1, MAPK1, and PRKCA) were common to all three sets (Figure S1C). Despite the many possible sources of variability and systematic differences, the results for CTNNB1 and CDH1 showed remarkably high concordance among all the three independent sets. For example, Pearson correlation coefficients for CTNNB1 expression levels were 0.92 (NCI vs. MDA PILOT, p<0.00001), 0.86 (NCI vs. MDA_CLSS, p<0.00001) and 0.84 (MDA_PILOT vs. MDA_CLSS, p<0.00001). The direct interaction of those proteins is well-established (24), and the correlation of protein expression levels is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that loss of CDH1 results in decreased levels of CTNNB (25). The results for MAPK1 showed the weakest correlation between NCI data and MDA_PILOT data (r=0.16, p=0.22), but, the correlation between MAPK1 levels in the different sets was higher than those between MAPK1 and the other shared protein features (Figure S1C). The correlation of ESR1 and PRKCA expression between the two MD Anderson data sets was very high (PRKCA: r=0.917, p<0.00001 and ESR1: r=0.93, p<0.00001), but there was only moderate correlation of the MD Anderson sets with NCI data (PRKCA: MDA_PILOT vs. NCI r=0.23, p=0.07, MDA_CLSS vs. NCI r=0.24, p=0.06, ESR1: MDA_PILOT vs. NCI r=0.29,p=0.02, MDA_CLSS vs. NCI r=0.26, p=0.04). The weak correlations might reflect any numbers of factors, such as differences in tissue culture conditions, methods for quantitating data, or specificity of antibodies used at the two institutions. For example, the antibody used to measure PRKCA in MDA_PILOT and MDA_CLSS recognizes an epitope that is reported to be specific to PRKCA, whereas the antibody used by the NCI is noted by its manufacturer to recognize PRKCB as well6. Despite those sometimes-weak correlations, measurements of a given protein in the three independent data sets were almost always as nearest neighbors in unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis of the shared proteins (Figure S1C). That observation supported the strategy of using the combined data from the 3 RPPA experiments to study the proteins associated with other features of the NCI60 cell lines.

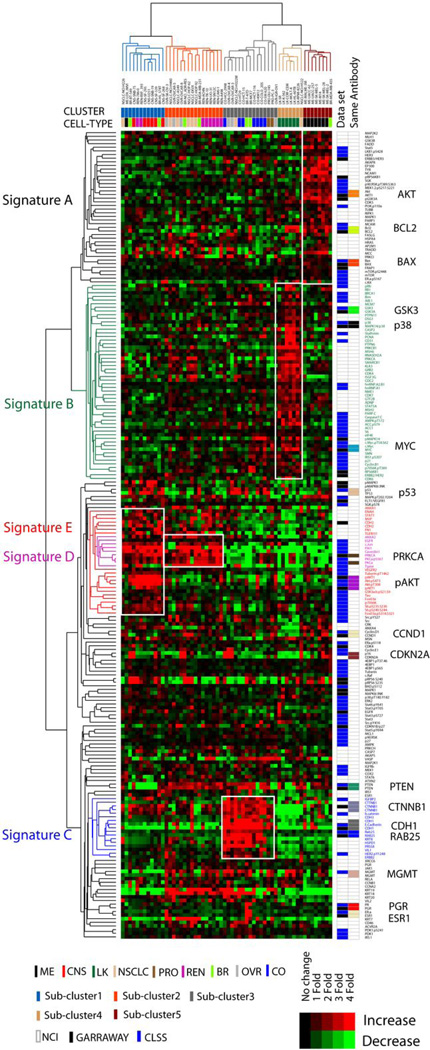

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the integrated RPPA data representing 222 protein features encompassing 167 unique features revealed 5 distinct clusters of cell lines (Figure 1). The clusters generally reflected the different tumor types in the NCI60 cell line set. Cluster 1 is mainly composed of brain tumor lines (CNS). The members of cluster 2 are mostly lung (NSCLC) and renal cell carcinomas (REN). Cluster 3 includes all of the colon (CO) cancer cell lines, as well as a few cell types from other lineages. Cluster 4 includes all of the leukemia (LK) cell lines. Cluster 5 is entirely composed of melanoma (ME), including MDA-MB-435. Although MDA-MB-435 was initially thought to be a breast cancer cell line, a variety of genotypic and phenotypic data confirm that it is melanoma in origin, a somewhat diverged version of M14 melanoma (6, 26, 27). Cluster 2 included 4 of 7 ovarian cell lines, including OV-CAR8_ADR-RES, which had originally been thought to be a derivative of MCF7 breast cancer and then was renamed an agnostic NCI_ADR-RES by DTP. Microsatellite fingerprinting and other molecular analyses indicate that it is actually a drug-resistant derivative of OV-CAR8 (26). Breast (BR) lines were scattered throughout the clusters, suggesting phenotypic heterogeneity. Overall 4 tumor types (CNS, ME, LK and CO) were significantly enriched within clusters, whereas the remaining 5 tumors types (BR, NSCLC, OVR, REN and PRO) were not associated with particular clusters by chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests (Table 1).

Figure 1.

RPPA analysis of the NCI 60 RPPA cell lines and tumor types. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis of the integrated proteomic data representing 222 protein features (167 unique features) from 3 independent NCI60 RPPA data sets is shown. The RPPA data sets were independently normalized and mean centered before integration. Categorization of the cells into one of 5 clusters is indicated by “CLUSTER” below the cell line names. The cancer cell type from which each cell line originated is indicated by “CELL-TYPE” below the color-coded label for “CLUSTER.” The groups of proteins that demonstrate increased expression characteristic of the different cell line clusters are indicated to the left (“Signature A – E”). The RPPA data set source for each protein is indicated to the right of the heatmap. Proteins assessed in more than one data set are also indicated (“Same Antibody”).

Table 1.

Association study of cancer cell types with integrated RPPA data of NCI 60 cell lines. 5 group chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test of cell types against clusters were performed.

| Cell Type | Chi-square Statistic |

Chi-square p-value |

Fisher’s exact_test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | 3.024286 | 0.553769 | 0.794203 |

| CNS* | 19.48026 | 0.000632 | 0.000721 |

| Colon* | 15.00478 | 0.004691 | 0.008337 |

| Leukemia* | 23.21053 | 0.000115 | 0.000123 |

| Lung | 4.386675 | 0.356197 | 0.442148 |

| Melanoma* | 24.31579 | 6.90E-05 | 7.34E-05 |

| Ovary | 5.485714 | 0.240988 | 0.356018 |

| Prostate | 5.114551 | 0.275744 | 0.648159 |

| Renal | 9.127127 | 0.057999 | 0.06333 |

Cell types showing significant enrichments in each specific sub-cluster.

We identified 5 groups of proteins (“A” – “E”) that were up-regulated in the clusters of cell lines described above (Figure S2). The proteomic signature A, characteristic of melanoma, includes total protein levels of several components of the PI3K–AKT signaling network (PI3K.p110, AKT, FRAP1, GSK3), but does not include any activation-specific markers for this pathway. Signature A also includes total proteins in the MAPK signaling pathway (HRAS, MAPK1, MAP2K2), and an activation-specific marker (MEK1&2_pS217_S221). Signature B, which is leukemia-specific, includes proteins involved in cellular proliferation (MCM7, PCNA, GRB2, EIF4E, IRS1, HNRNPA1, c-MYC, c-MYC_pT58S62) and cell cycle progression (CDC2, CDK4, CDK7, CCNB1, CDKN1A), compatible with the high proliferative rates of leukemia cell lines. Signature C consists mainly of colon cancer lines and includes proteins involved in cell adhesion (CTNNB1, CDH1, CDH3). CDH1 (MDA_PILOT data) shows the most dramatic increase in expression in cluster C (97 fold increase versus the other clusters). Signature D reflects proteins highly expressed in cell line cluster 2 with mixed cell lineages. Signature D includes a group of tightly-correlated proteins: PRKCA, PRKCA_pS567, CAV1, C-JUN, EGFR and TGM1. Finally, signature E is CNS-specific and reflects activation of the PI3K–AKT pathway. Many activation-specific proteins forms in the pathway were expressed at high levels in the cluster (AKT_pS473, AKT_pT308, GSK3α&β_pS21_S9, FOXO3A_pS318_S321, RPS6KB1_pS235_S236, RPS6KB1_pS240_S244).

Association of mutations with proteomic signatures

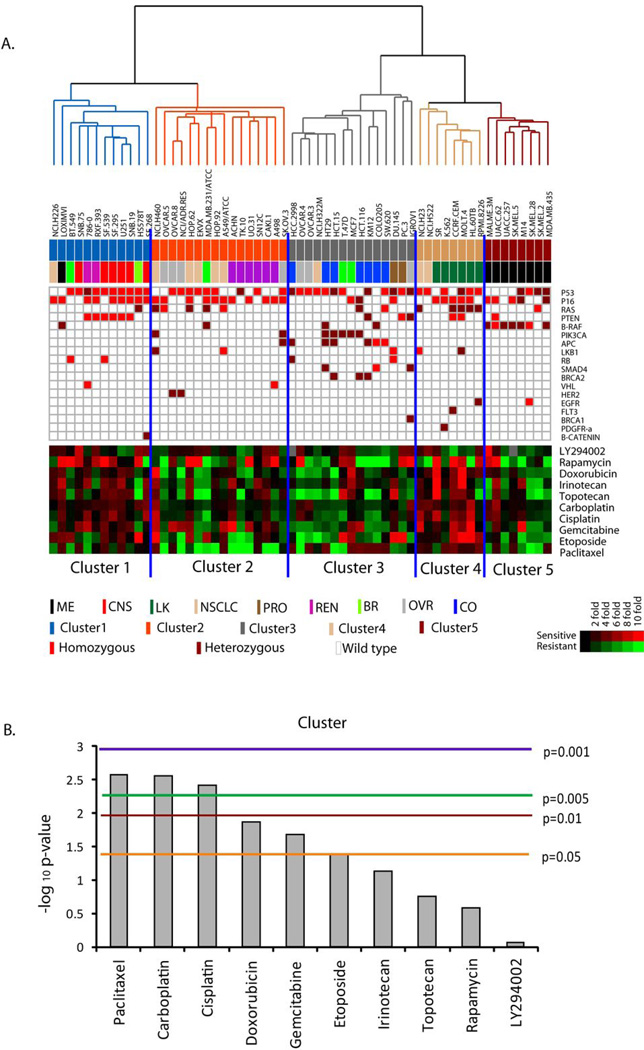

Recently, the mutation status of 24 cancer-related genes was determined for all of the NCI60 cell lines and identified oncogenic mutations in 20 of the genes (23). To assess systematically the relationship between cancer-prevalent mutations and patterns of protein expression and activation, we measured the associations between those mutations and the proteomic signatures of the NCI60 (Figure 2A). When contingency table analysis with five-group chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests was applied, the mutations in four genes (PTEN, BRAF, PIK3CA, APC) were significantly enriched in particular RPPA-derived clusters (Table 2). Mutations in BRAF were significantly enriched in cluster 5 (7 out of 8 cell lines, p = 0.006 by chi-square test). Homozygous mutations of PTEN were most enriched in cluster 1 (p =0.048 in Fisher’s exact test). The presence of any mutation in PTEN was also enriched in cluster 1, but this was not statistically significant (6 out of 12 cell lines, p= 0.136 by chi-square test). Mutation in PIK3CA was enriched in cluster 3 (6 out of 7 cell lines), although that trend did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.103 by chi-square test). Similarly, mutations in APC, BRCA2 and SMAD4 were more abundant in cluster 3, but their enrichment did not reach statistical significance. Because the 5 clusters of cell lines identified by protein features partly reflected tumor types in the NCI60, we carried out nine-group chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests to assess the association between mutation status and cancer cell type (Table S2). As predicted by previous studies, mutation of BRAF was significantly enriched in the melanoma cell lines (p = 0.010 by chi square test), whereas mutations in APC and BRCA2 were significantly enriched in colon cancer cell lines (p=0.0038 and p=0.037, respectively). Among the four mutated genes (PTEN, BRAF, PIK3CA, APC) most significantly associated with RPPA clusters, BRAF and APC were associated with specific cancer cell lineages. Mutations in PTEN and PIK3CA did not associate with specific cancer cell lineages, but they were the most highly associated with specific, but distinct, proteomic signatures.

Figure 2.

Association of the NCI60 RPPA signatures with mutations and drug sensitivity. (A) Cell lines are organized by the results of unsupervised clustering analysis of the RPPA data (Figure 1). RPPA cluster and the cell type are indicated below the cell line labels. Mutations identified in each cell line are indicated in the table below (Homozygous mutations = orange squares; Heterozygous mutations = brown squares). The heatmap represents the negative log10 GI50 values of 10 standard anti-cancer agents. GI50 values were median-centered (Red = high value, i.e. sensitive; Green = low value, i.e. resistant). (B) Results of 5 group one-way ANOVA analysis of the GI50 values for each of the agents for the NCI60 cell lines. Y-axis, negative log 10 p-values. The colored horizontal lines indicate various p-value cutoffs.

Table 2.

Association study of mutation status with integrated RPPA data of NCI 60 cell lines. 5 group chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test of mutation status against sub-clusters were performed.

| Total | Homozygous | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Chi-square p-value |

Fisher’s exact test p-value |

Chi-square p-value |

Fisher’s exact test p-value |

| P53 | 0.927015 | 0.935214 | 0.555924 | 0.575416 |

| P16 | 0.450216 | 0.427948 | 0.250227 | 0.230189 |

| RB | 0.343613 | 0.441297 | 0.353376 | 0.417028 |

| PTEN* | 0.135962 | 0.109034 | 0.059305 | 0.047797 |

| PIK3CA | 0.103316 | 0.198385 | NaN | 1 |

| LKB1 | 0.394828 | 0.519535 | 0.754997 | 0.913696 |

| APC* | 0.028054 | 0.058023 | 0.253053 | 0.634973 |

| SMAD4 | 0.102952 | 0.173347 | 0.592418 | 1 |

| VHL | 0.696682 | 0.860656 | 0.696682 | 0.860656 |

| RAS | 0.240045 | 0.306594 | 0.665184 | 0.808537 |

| B-RAF* | 0.006084 | 0.01228 | 0.032172 | 0.039891 |

| FLT3 | 0.217584 | 0.283333 | NaN | 1 |

| BRCA1 | 0.592418 | 1 | NaN | 1 |

| BRCA2 | 0.102952 | 0.173347 | NaN | 1 |

| HER2 | 0.293537 | 0.636066 | NaN | 1 |

| EGFR | 0.293537 | 0.119672 | 0.217584 | 0.283333 |

| PDGFR-a | 0.217584 | 0.283333 | NaN | 1 |

| B-CATENIN | 0.451529 | 0.483333 | NaN | 1 |

Mutants showing significant enrichments in each specific sub-cluster.

To identify unique associations between mutations and RPPA cell line clusters, we performed “two-group” chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests in which each cluster was compared with the rest of cell lines for enrichment with unique mutations. Homozygous mutations in PTEN were significantly associated with cluster 1 (p =0.024, chi-square test; p =0.016, Fisher’s exact test), whereas cluster 2 was notable for a lack of mutation in PTEN (p=0.095, by chi-square test) (Table S3, Table S4). Mutations in PIK3CA (p = 0.039, chi-square test; p=0.023, Fisher’s exact test), APC (p=0.005; p=0.003), BRCA2 (p=0.034; p=0.022), and SMAD4 (p=0.034; p=0.022) were enriched in cluster 3. Cluster 4 was not associated with any mutation set, probably because leukemias are frequently characterized by chromosomal rearrangements of oncogenes rather than missense mutations. Mutations in BRAF were significantly enriched in cluster 5 (p=0.001, chi-square; p=0.001, Fisher’s exact test), consistent with the high prevalence of that mutation in melanoma.

The opposing associations of two clusters (clusters 1 and 2) with mutation in PTEN are intriguing. The clusters have similar proteomic signatures, as demonstrated by their proximity in the unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Figure 1). To identify protein features that distinguish cluster 1 and cluster 2, we carried out two-sample t-tests and found that expression of 6 protein features (KRT18, KRT19, PTEN [MDA PILOT], PTEN [MDA CLSS], MGMT, TGM1) and phosphorylation of 6 protein features (AKT_pT308 [MDA_CLSS], AKT_pS473 [MDA_CLSS], AKT_pS473 [MDA_PILOT], MAPK14_pT180.Y182, RPS6KA1_pT389_S363, TSC2_pT1462) were significantly different (p<0.001; Figure S3). PTEN expression was significantly higher (9.4 fold and 8.6 fold) in cluster 2, whereas phosphorylation of AKT was significantly higher in cluster 1 (AKT_pS473: 4.95 fold, AKT_pT308: 3.675 fold). Although PTEN mutations were enriched in cluster 1, approximately 50% of the cell lines in that cluster do not harbor PTEN mutations and show normal PTEN expression. Thus, other genetic events are also sufficient to result in the observed pattern of protein expression, and/or contribute to the pattern of protein expression observed in the PTEN-null cell lines in the cluster.

Protein signatures, mutation status, and drug sensitivity

We next investigated the relationship between proteomic profiles of the NCI60 cell lines and their sensitivity to anticancer agents. Analysis of the GI50 values for the NCI60 cell lines for a set of commonly used agents showed marked differences in average sensitivity among the 5 clusters of cell lines (Figure 2A; Figure S4). Cluster 1, which is characterized by increased levels of activation-specific markers in the PI3K–AKT pathway, showed high sensitivity to rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR. In contrast, cluster 5, which is characterized by expression of total- but not activation-specific markers in the PI3K–AKT pathway, was less sensitive to rapamycin. Cluster 2, which demonstrates similarity to cluster 1 by hierarchical clustering but lacks the signature of PI3K–AKT pathway activation, was also less sensitive to rapamycin. Cluster 2 is characterized by lower sensitivity to paclitaxel and doxorubicin in relation to other clusters. Cell lines in cluster 4 showed high sensitivity to most of the chemotherapeutic agents. Paclitaxel (p=0.0026 by one-way ANOVA), carboplatin (p=0.0028) and cisplatin (p=0.0038) showed the most significant differences in sensitivity of the cells as a function of cell cluster (Figure 2B).

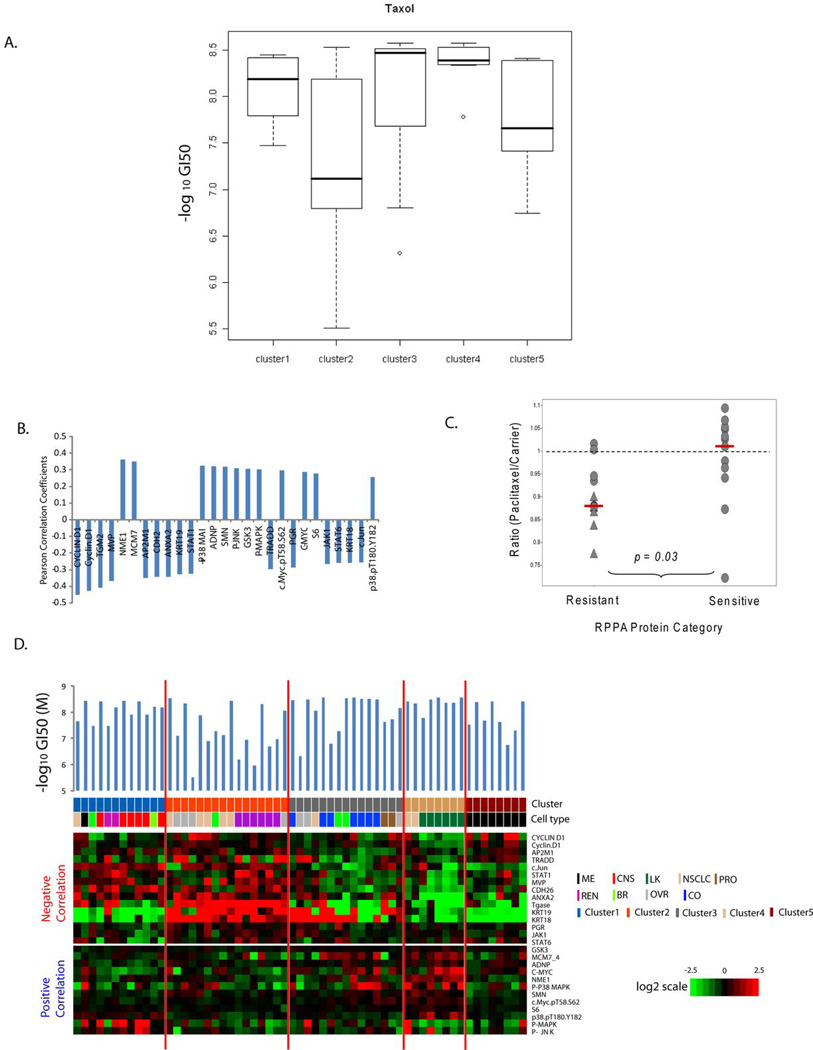

Figure 3A shows the variation in GI50 values for paclitaxel within each RPPA-defined cluster. Most of the cells in cluster 4 were highly sensitive to paclitaxel. Cluster 2 was least sensitive to paclitaxel but showed a very wide range of drug responses suggesting that other factors are responsible for the heterogeneity. Nine group one-way ANOVA analysis for estimation of the influence of cancer cell type on paclitaxel showed significant differences (p=0.0041) implying that drug sensitivity differences are related in part to cell lineage differences. Three cell types, CNS, colon and leukemia, showed the most sensitivity to paclitaxel whereas renal cell carcinoma showed the least sensitivity (Figure S5). The melanomas, lung cancers, ovarian cancers and renal cell carcinomas showed wide ranges of drug sensitivity, reflecting the apparent heterogeneity of those cell types.

Figure 3.

Protein factors associated with paclitaxel responsiveness in the NCI60 panel. (A). Box-plot analysis of negative log10 GI50 values for paclitaxel in each RPPA-defined cluster. (B) Pearson correlation coefficients for proteins significantly correlated with paclitaxel response across the NCI 60 cell lines (p-values for the Pearson correlation < 0.05). Positive values indicate that high expression is associated with high sensitivity; negative values reflect association with paclitaxel resistance. (C) Effect of proteins significantly associated with paclitaxel sensitivity on relative growth of lung cancer cells in the presence of paclitaxel. The results of a previously published whole genome siRNA library +/− paclitaxel synthetic lethality screen (28) were reviewed. Y-axis, ratio of relative growth for cells in the presence of siRNA with paclitaxel to siRNA with vehicle. The dotted line indicates Paclitaxel/Carrier ratio of 1. The red bars indicate the median of each group. ▲, significant difference (p < 0.05) for growth in the presence of paclitaxel versus carrier. (D) Expression of proteins significantly correlating with paclitaxel GI50 values in the NCI60. Cells are organized by the results of unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the RPPA data (Figure 1). Heat maps show protein expression levels negatively (upper panel) and positively (lower panel) correlated with sensitivity. The RPPA cluster and cell type for each cell line are indicated. The –Log10 GI50 value for paclitaxel for each cell line is presented above the heatmap.

Comparisons of RPPA data with GI50 values for paclitaxel across the cell lines identified 27 protein features significantly correlated by Pearson correlation coefficient (p<0.05) (Table 3). Two proteins (CCND1 and Phospho-P38 MAPK) showed significant Pearson correlations in two independent RPPA experiments; thus 25 unique features were identified. Expression of CCND1 showed the most negative correlation with paclitaxel sensitivity (r=-0.452, p=0.00033). Levels of transglutaminase 2 (TGM2), lung-resistance related protein (MVP), clathrin adaptor protein 50 (AP2M1), annexin A2 (ANXA2), n-cadherin (CDH2), STAT1, and keratin 19 (KRT19) were also significantly correlated with resistance (Figure 3B). Metastasis inhibition factor NM23 (NME1) showed the highest positive correlation with paclitaxel sensitivity (r=0.364 p=0.00464). MCM7, ADNP, GSK3, SMN1, and MYC expression levels also correlated positively with paclitaxel sensitivity. To assess the functional effects of those genes on paclitaxel sensitivity, we reviewed the results of a whole-genome siRNA synthetic lethality screen performed with paclitaxel in a human lung cancer cell line (Table 3) (28). In that screen, the effect of each gene on paclitaxel sensitivity was assessed by determining the ratio of the cell viability score for the combination of gene knockdown in the presence and the absence of paclitaxel. A Paclitaxel/Carrier less than 1 suggests that gene knockdown results in increased sensitivity to paclitaxel, and thus supports that gene is a mediator of paclitaxel resistance. Overall, the proteins significantly associated with resistance to paclitaxel by RPPA had a lower ratio of Paclitaxel/Carrier cell viability than the proteins associated with sensitivity (p = 0.03) (Figure 3C). Eleven of the 13 proteins that correlated with paclitaxel resistance by RPPA had a Paclitaxel/Carrier ratio < 1, and 5 of those proteins demonstrated a statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference in growth in the presence of paclitaxel. Among the proteins correlated with sensitivity to paclitaxel, only 5 of the 12 had a ratio < 1, and none showed statically significant difference in growth (Table 3).

Table 3.

Proteins that correlate with paclitaxel sensitivity.

| Protein | RPPA Category |

RPPA vs -Log GI50 r value |

RPPA Vs -Log GI50 p value |

Gene Symbol | siRNA Average Viability [Paclitaxel] |

siRNA Average Deviation [Paclitaxel] |

siRNA Average Viability [Carrier] |

siRNA Average Deviation [Carrier] |

siRNA Ratio [Paclitaxel/ Carrier] |

siRNA Paclitaxel Versus Carrier P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCND1 | Resistant | −0.452 | <0.001 | CCND1 | 0.651 | 0.044 | 0.839 | 0.026 | 0.776 | 0.023 |

| TGM2 | Resistant | −0.411 | 0.001 | TGM2 | 0.678 | 0.007 | 0.752 | 0.016 | 0.902 | 0.007 |

| MVP | Resistant | −0.370 | 0.004 | MVP | 0.688 | 0.035 | 0.783 | 0.022 | 0.878 | 0.0644 |

| AP2M1 | Resistant | −0.349 | 0.007 | AP2M1 | 0.766 | 0.021 | 0.872 | 0.031 | 0.878 | 0.052 |

| CDH2 | Resistant | −0.345 | 0.007 | CDH2 | 0.684 | 0.028 | 0.779 | 0.016 | 0.878 | 0.038 |

| ANXA2 | Resistant | −0.344 | 0.008 | ANXA2 | 0.669 | 0.074 | 0.760 | 0.052 | 0.881 | 0.261 |

| KRT19 | Resistant | −0.328 | 0.011 | KRT19 | 0.644 | 0.021 | 0.689 | 0.044 | 0.935 | 0.292 |

| STAT1 | Resistant | −0.326 | 0.012 | STAT1 | 0.761 | 0.030 | 0.877 | 0.018 | 0.868 | 0.016 |

| TRADD | Resistant | −0.298 | 0.022 | TRADD | 0.897 | 0.032 | 1.070 | 0.060 | 0.838 | 0.035 |

| PGR | Resistant | −0.289 | 0.026 | PGR | 0.935 | 0.047 | 0.931 | 0.014 | 1.004 | 0.931 |

| JAK1 | Resistant | −0.265 | 0.042 | JAK1 | 1.039 | 0.037 | 1.183 | 0.030 | 0.879 | 0.019 |

| KRT18 | Resistant | −0.260 | 0.047 | KRT18 | 1.042 | 0.004 | 1.025 | 0.037 | 1.017 | 0.698 |

| STAT6 | Resistant | −0.260 | 0.046 | STAT6 | 0.766 | 0.024 | 0.810 | 0.034 | 0.946 | 0.274 |

| S6 | Sensitive | 0.28 | 0.032 | RPS6 | 0.831 | 0.008 | 0.789 | 0.027 | 1.053 | 0.134 |

| MYC; MYCpT58 |

Sensitive Sensitive |

0.288 0.296 |

0.027 0.023 |

MYC | 0.710 | 0.032 | 0.814 | 0.046 | 0.873 | 0.086 |

| P-MAPK | Sensitive | 0.303 | 0.019 | MAPK1 | 0.892 | 0.025 | 0.926 | 0.012 | 0.963 | 0.191 |

| (P-MAPK) | Sensitive | 0.303 | 0.019 | MAPK3 | 0.869 | 0.039 | 0.814 | 0.023 | 1.068 | 0.191 |

| GSK3α/β | Sensitive | 0.306 | 0.019 | GSK3 | 1.116 | 0.063 | 1.140 | 0.049 | 0.979 | 0.714 |

| (GSK3α/β) | Sensitive | 0.306 | 0.019 | GSK3 | 1.152 | 0.080 | 1.099 | 0.054 | 1.048 | 0.531 |

| P-JNK | Sensitive | 0.309 | 0.017 | MAPK8 | 1.079 | 0.047 | 0.986 | 0.016 | 1.095 | 0.078 |

| SMN1 | Sensitive | 0.318 | 0.014 | SMN1 | 0.596 | 0.287 | 0.825 | 0.042 | 0.722 | 0.369 |

| ADNP | Sensitive | 0.323 | 0.013 | ADNP | 1.081 | 0.053 | 1.053 | 0.041 | 1.027 | 0.627 |

| P-P38 | Sensitive | 0.325 | 0.012 | MAPK14 | 0.914 | 0.050 | 0.886 | 0.018 | 1.032 | 0.518 |

| MCM7 | Sensitive | 0.351 | 0.006 | MCM7 | 0.885 | 0.016 | 0.940 | 0.029 | 0.941 | 0.097 |

| NME1 | Sensitive | 0.364 | 0.005 | NME1 | 0.958 | 0.040 | 0.949 | 0.012 | 1.010 | 0.800 |

| Median | Resistant | −0.328 | 0.011 | 0.761 | 0.030 | 0.839 | 0.030 | 0.879 | 0.052 | |

| Median | Sensitive | 0.306 | 0.019 | 0.892 | 0.040 | 0.926 | 0.029 | 1.010 | 0.191 |

For antibodies that recognize more than one protein (i.e. GSK3αβ recognizes both GSK3α and GSK3β), the results for siRNA against each protein is presented. Both Total and Phospho MYC protein levels correlated with sensitivity to paclitaxel. For siRNAs that demonstrated a significant difference (p < 0.05) for growth in the presence of paclitaxel as compared the carrier, the related proteins and p-values presented in bold text.

Assessment of the expression levels of the significantly correlated proteins across the NCI60 cell lines reflected the differences in paclitaxel sensitivity observed across the RPPA-based clusters (Figure 3D). TGM2 and ANXA2 were highly expressed in cluster 2 (least sensitive to paclitaxel), whereas they were expressed at the lowest levels in cell lines in cluster 4 (most sensitive to paclitaxel). MYC, MCM7 and NME1 were expressed at the highest levels in cluster 4 (as part of RPPA signature B for cluster 4). We surmise that the differences in sensitivity to paclitaxel result in part from differences in protein signaling that are the cumulative outcomes of differences in cell type and mutation status.

Discussion

There is a great need to improve our understanding of the molecular characteristics and heterogeneity of cancer. The NCI60 is a powerful tool for such studies, due to the wealth of data publicly available about those cell lines (1–6). Although much is known about the DNA, RNA, and pharmacologic aspects of the lines, data on protein expression and activation is much more limited. Previous proteomic analyses of the NCI60 have yielded important information, including the marked lack of correlation between protein and mRNA expression levels for several families of proteins (14, 18). However, those studies did not include a direct assessment of the activation status of signaling pathways. We have extended the available body of data available on the NCI60 by performing RPPA analysis using activation-specific markers for several cell signaling pathways. We have used those data in concert with other available proteomic data to extend our understanding of the patterns of protein expression and activation that characterize different tumor types, cancer-prevalent mutations, and drug sensitivities.

Comparison of the protein expression data from three independent RPPA studies of the NCI60 demonstrate that proteomic signatures are relatively robust and reproducible, even when generated in completely independent laboratories. Supporting the robustness of the proteomic analysis of a relatively small number of features, the RPPA-derived clusters of the NCI-60 cell lines largely recapitulate the results observed by whole genome mRNA profiling (6). That conclusion is most clearly indicated by assignment of the MDA MB 435 cell line to the melanoma cluster, as has been demonstrated in a number of transcriptional profiling studies and microsatellite fingerprinting (6, 26). The addition of activation-specific markers provides further information about the distinctions between the groups of cell lines. For example, although clusters 1 and 2 are closely related by hierarchical cluster analysis, there are marked differences between the two clusters in the levels of activation-specific markers in the PI3K–AKT signaling pathway (Figure 1, Figure S3). In contrast, the two clusters did not differ significantly in total protein expression levels for the majority of the pathway components, such as AKT. In addition, cluster 5 was characterized by increased total-protein levels of several components of the PI3K–AKT pathway, but it did not feature increased activation-specific pathway markers. The functional significance of that additional information is reflected in an increased sensitivity to rapamycin, an inhibitor of signaling downstream of AKT, in cluster 1 in comparison with clusters 2 and 5. Thus, the inclusion of activation-specific markers provides insight into the functional differences between these otherwise closely-related groups of cells.

In this study we have performed the first systematic comparison of the oncogenic mutations in the NCI60 with their proteomic profiles. As described above, although clusters 1 and 2 share many protein features, only cluster 1 has a proteomic signature that includes elevated phospho-protein levels of several components of the PI3K–AKT pathway (AKT, TSC2, GSK3, S6, FOXO3A). Cluster 1 is highly enriched with PTEN mutations. While activation of PI3K–AKT signaling is significantly associated with the mutation status of PTEN, it is not associated with the mutation status of PIK3CA (clusters 1 and 3). This observation is consistent with our previous analysis of a much smaller set of proteins, including phospho-AKT, in the NCI60 cell lines, as well as an analysis of an independent panel of breast cancer cell lines and clinical specimens (20, 22). Thus, the protein expression data and mutation status complement each other to provide understanding not available from either alone.

There is a great need for biomarkers to predict responsiveness to anti-cancer agents. A number of previous analyses have used the abundant pharmacologic data for the NCI60 cell lines to test associations between drug sensitivity and DNA copy numbers, DNA methylation, mRNA and miRNA expression, and oncogenic mutations (3, 29–32). We have performed a pilot analysis of the expanded RPPA protein expression data with drug sensitivity for a panel of 10 commonly used agents. In addition to the previously noted association of rapamycin sensitivity with increased expression of activation-specific markers in the PI3K–AKT pathway, we examined protein features associated with sensitivity to several commonly used cytotoxic agents. We identified 25 unique protein features significantly associated with sensitivity to paclitaxel. The correlations with sensitivity and resistance by RPPA matched functional results for the proteins in a published paclitaxel whole genome siRNA synthetic lethality screen (28). Those findings indicate the likely benefit of additional studies that expand the approach to the larger collection of agents for which sensitivity is known for the NCI60 cell lines. In addition, it will be important to integrate the proteomic data with other molecular characteristics of the cell lines for such analyses, as has proved beneficial in multiple studies (17, 31–33).

In conclusion, this study again demonstrates the tremendous potential of the RPPA technology to provide information about the status of protein networks in cancer. Our analyses suggest that the reproducibility of the RPPA data is such that assimilating data from multiple sources is feasible, and that may help overcome the limitation of the relatively small number of markers that can be assessed in individual studies. The inclusion of phosphorylation-specific antibodies in our RPPA analysis improves the ability to assess protein networks functionally. However, many other functional aspects of protein networks remain to be assessed. The data here supports the hypothesis that such direct analyses of protein networks may improve our understanding of the underpinnings of cancer. When integrated with other available data, the information may lead to more effective therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by MDACC Melanoma Spore Development Grant (MAD). The M. D. Anderson Reverse Phase Protein Array Core Facility is supported by an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CA-16672).

Footnotes

References

- 1.Shoemaker RH. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blower PE, Verducci JS, Lin S, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles for the NCI-60 cancer cell panel. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1483–1491. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bussey KJ, Chin K, Lababidi S, et al. Integrating data on DNA copy number with gene expression levels and drug sensitivities in the NCI-60 cell line panel. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:853–867. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrich M, Turner J, Gibbs P, et al. Cytosine methylation profiling of cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4844–4849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712251105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaur A, Jewell DA, Liang Y, et al. Characterization of microRNA expression levels and their biological correlates in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2456–2468. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross DT, Scherf U, Eisen MB, et al. Systematic variation in gene expression patterns in human cancer cell lines. Nat Genet. 2000;24:227–235. doi: 10.1038/73432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scherf U, Ross DT, Waltham M, et al. A gene expression database for the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Nat Genet. 2000;24:236–244. doi: 10.1038/73439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein JN, Myers TG, O’Connor PM, et al. An information-intensive approach to the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Science (New York, NY. 1997;275:343–349. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dan S, Tsunoda T, Kitahara O, et al. An integrated database of chemosensitivity to 55 anticancer drugs and gene expression profiles of 39 human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1139–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ring BZ, Chang S, Ring LW, Seitz RS, Ross DT. Gene expression patterns within cell lines are predictive of chemosensitivity. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallqvist A, Rabow AA, Shoemaker RH, Sausville EA, Covell DG. Establishing connections between microarray expression data and chemotherapeutic cancer pharmacology. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:311–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JS, Chu IS, Mikaelyan A, et al. Application of comparative functional genomics to identify best-fit mouse models to study human cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1306–1311. doi: 10.1038/ng1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweet-Cordero A, Mukherjee S, Subramanian A, et al. An oncogenic KRAS2 expression signature identified by cross-species gene-expression analysis. Nat Genet. 2005;37:48–55. doi: 10.1038/ng1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shankavaram UT, Reinhold WC, Nishizuka S, et al. Transcript and protein expression profiles of the NCI-60 cancer cell panel: an integromic microarray study. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:820–832. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens EV, Nishizuka S, Antony S, et al. Predicting cisplatin and trabectedin drug sensitivity in ovarian and colon cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:10–18. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian Q, Stepaniants SB, Mao M, et al. Integrated Genomic and Proteomic Analyses of Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:960–969. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400055-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varambally S, Yu J, Laxman B, et al. Integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of prostate cancer reveals signatures of metastatic progression. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishizuka S, Charboneau L, Young L, et al. Proteomic profiling of the NCI-60 cancer cell lines using new high-density reverse-phase lysate microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14229–14234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2331323100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies MA, Stemke-Hale K, Lin E, et al. Integrated molecular and clinical analysis of AKT activation in metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1985. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stemke-Hale K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lluch A, et al. An integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6084–6091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tibes R, Qiu Y, Lu Y, et al. Reverse phase protein array: validation of a novel proteomic technology and utility for analysis of primary leukemia specimens and hematopoietic stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2512–2521. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasudevan KM, Barbie DA, Davies MA, et al. AKT-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikediobi ON, Davies H, Bignell G, et al. Mutation analysis of 24 known cancer genes in the NCI-60 cell line set. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2606–2612. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeanes A, Gottardi CJ, Yap AS. Cadherins and cancer: how does cadherin dysfunction promote tumor progression? Oncogene. 2008;27:6920–6929. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herzig M, Savarese F, Novatchkova M, Semb H, Christofori G. Tumor progression induced by the loss of E-cadherin independent of [beta]-catenin//Tcf-mediated Wnt signaling. Oncogene. 2006;26:2290–2298. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenzi PL, Reinhold WC, Varma S, et al. DNA fingerprinting of the NCI-60 cell line panel. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:713–724. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikheev AM, Mikheeva SA, Rostomily R, Zarbl H. Dickkopf-1 activates cell death in MDA-MB435 melanoma cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;352:675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitehurst AW, Bodemann BO, Cardenas J, et al. Synthetic lethal screen identification of chemosensitizer loci in cancer cells. Nature. 2007;446:815–819. doi: 10.1038/nature05697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JK, Havaleshko DM, Cho H, et al. A strategy for predicting the chemosensitivity of human cancers and its application to drug discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13086–13091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorenzi PL, Llamas J, Gunsior M, et al. Asparagine synthetase is a predictive biomarker of L-asparaginase activity in ovarian cancer cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3123–3128. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen L, Kondo Y, Ahmed S, et al. Drug sensitivity prediction by CpG island methylation profile in the NCI-60 cancer cell line panel. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11335–11343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staunton JE, Slonim DK, Coller HA, et al. Chemosensitivity prediction by transcriptional profiling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:10787–10792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191368598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma Y, Ding Z, Qian Y, et al. An integrative genomic and proteomic approach to chemosensitivity prediction. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:107–115. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]