Abstract

Multiple donors are generally available for haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Here we discuss the factors that should be considered when selecting donors for this type of transplantation according to the currently available evidence. Donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies (DSAs) increase the risk of graft failure and should be avoided whenever possible. Strategies to manage recipients with DSAs are discussed. One should choose a full haplotype mismatch rather than a better-matched donor and maximize the dose of infused hematopoietic cells. Donor age and sex are other important factors. Other factors, including predicted natural killer cell alloreactivity and consideration of noninherited maternal alleles, are more controversial. Larger studies are needed to further clarify the role of these factors for donor selection in haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Keywords: Haploidentical stem cell, transplantation, Anti-HLA antibodies, Donor selection

Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is increasingly used for treatment of malignancies and immune and hematologic diseases. This is largely related to the development of posttransplantation cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate as an effective regimen for prevention of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [1]. Recent studies have confirmed the efficacy of this approach, with both nonmyeloablative and reduced-intensity ablative conditioning [1–3]. There is increasing interest in this regimen with haploidentical transplants owing to a relatively low rate of treatment-related mortality (TRM), low costs of drugs and associated supportive care, and rapid availability of donors when an urgent transplantation is needed.

Given that multiple mismatched related donors may be available for transplantation, it is important to select the donor most likely to produce a successful outcome. Parents, children, and half-matched siblings are usually available for a given patient. Here we discuss considerations for selection of a haploidentical donor based on the current available evidence.

DONOR-SPECIFIC HLA ANTIBODIES

Haploidentical transplant recipients may have anti-HLA antibodies against donor HLA antigens, induced by antigen exposure during previous pregnancy or by blood product transfusions. Some patients, particularly parous females, are highly alloimmunized, with high titers of antibodies against a broad range of HLA antigens. The presence of donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies (DSAs), identified by single antigen beads in a Luminex platform, are reportedly associated with graft failure with all forms of transplantation [4–7]. Whether this is a direct effect of the antibodies or an associated T cell response is unclear. DSAs may possibly block access of stem cells to the stem cell niche, decreasing available progenitor cells to engraft, and ultimately decrease the stem cell dose necessary to achieve effective engraftment, as suggested by some preclinical studies [8].

The presence of DSAs has been associated with an increased risk of graft failure in HSCT, including in matched unrelated donor (MUD) graft recipients, who are selected to be matched for HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1 but are usually mismatched at the HLA-DP locus [4–7]. Engraftment is favored by large cell doses of transplanted cells, possibly by adsorption of the HLA antibodies. T cell—depleted haploidentical transplants appear to be especially predisposed to graft failure in the presence of DSA, most likely due to the lower cell dose and absence of T cells in the graft [4, 5]. In our recent analysis, DSAs were the single most important cause of graft failure in MUD transplants [5], whereas in cord blood transplants, the role of infused cell numbers in addition to DSAs has been emphasized [6, 7].

The levels of donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies may be important, given that different antibody levels have been associated with the risk of primary graft failure in different types of HLA-mismatched transplants. T cell—depleted haploidentical transplant recipients with a DSA level of ~1500 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) were found to have a high rate of primary graft failure [3], as did MUD transplant recipients with DSA against the HLA-DPB1 locus with levels >2500 MFI [4]. In cord blood transplants, levels >1000 MFI appeared to be deleterious to engraftment [6], whereas TCR-haploidentical transplant recipients who failed to engraft had DSA levels >5000 MFI [9].

Graft failure is not substantially increased if the recipient has anti-HLA antibodies that do not react with donor specificities [5]. One should select a donor with an HLA type that is nonreactive with the recipient’s antibodies or who has a low DSA titer, ideally <1000 MFI [3–7]. If a patient has high DSA levels against all related donors, it may be possible to identify an unrelated donor mismatched for a single HLA antigen (9/10 MUD) that is not targeted by the recipient’s anti-HLA antibodies. Many recipients are broadly allosensitized and have high titers of DSA against the mismatched HLA antigens in all potential donors. How to best manage these patients to prevent graft rejection is unclear. Selecting donors with the lowest number of loci with DSA against and/or the lowest antibody levels is reasonable, as is treatment of allosensitized recipients before transplantation to decrease antibody levels using plasma exchange, rituximab, and i.v. gamma globulin [3]. This strategy has been reported to be effective for solid organ transplants, but its efficacy in HSCT remains to be confirmed in clinical trials.

MAXIMIZING THE NUMBER OF STEM CELLS INFUSED BY CHOOSING ABO-MATCHED DONORS

Numerous studies have demonstrated that infusion of larger numbers of bone marrow cells improves survival after HSCT [10–12]. Rocha et al. [10] reported that doses above the mean (2.6 × 108 total nucleated cells [TNCs]/kg recipient body weight) were associated with superior outcomes with lower nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and disease relapse and improved disease-free survival. Neutrophil recovery and platelet recovery were faster, and the risk of GVHD was not increased. Patients who received >3.8 × 108 TNCs/kg had approximately 30% better disease-free survival compared with those who received <1.6 × 108 TNCs/kg [9]. These results were confirmed in a subsequent study of patients with various hematologic malignancies and different donor types, which showed that these effects were more pronounced in patients age >30 years with advanced disease and with alternative donor sources [11].

Although it has not yet been shown specifically in haploidentical bone marrow transplantation, cell dose is likely an important determinant of treatment outcome. Haploidentical HSCT has been associated with intense bidirectional alloreactivity, including a higher predisposition toward graft rejection compared with HLA-matched HSCT. Engraftment is favored by infusion of large doses of CD34+ cells; with T cell—depleted haploidentical transplants, “megadoses” of stem cells are needed to reliably achieve engraftment [13, 14]. The optimal dose for T cell—replete transplants is unknown. Based on current knowledge, it is desirable to administer the maximum dose of bone marrow cells, with a goal of at least 3 × 108 TNCs/kg. T cell—replete haploidentical transplants generally use bone marrow cells. One approach to obtaining higher cell doses is to use granulocyte colony-stimulating factor—mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cells. This approach is under evaluation, but there is a concern that this cell source may be associated with a higher rate of GVHD.

If maximizing the infused stem cell dose is important, then the highest cell yields of bone marrow harvests are from young, larger donors. Transplants involving a major ABO incompatibility requires mononuclear cell separation to prevent a hemolytic reaction; this reduces the transplanted cell dose and may predispose to graft failure [15, 16]. If possible, an ABO-compatible donor should be selected to avoid manipulation of the graft that could reduce the cell dose [16]. Our experience at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in recipients with minor and major ABO-incompatible donors has shown average decreases of 11% and 34%, respectively, in CD34+ cells/kg after processing and of 34% and 67% in TNC cells. This suggests that if no ABO compatible donor is available, then a donor with a minor ABO mismatch is preferred over a donor with a major mismatch, because the former is less likely to affect the number of cells infused. Ensuring an adequate graft is the first step in promoting engraftment and successful transplantation.

CHOOSING A FULL HAPLOTYPE MISMATCH RATHER THAN A BETTER-MATCHED DONOR

Historically, a progressive increase in TRM has been reported with increasing genetic disparity in transplantation from related or unrelated donors using conventional GVHD prophylaxis [17–19]. The incidence of acute GVHD (aGVHD) and TRM increased progressively with an increasing number of mismatches [17]. In contrast to these findings, Kasamon et al. [20] reported no increased incidence of aGVHD and NRM with full haplotype-mismatched transplantations using posttransplantation cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, and mycophanolate immunosuppression. In their multivariate analysis, patients with more than 3 mismatches appeared to have better outcomes, based on a lower risk of relapse [20]. The presence of HLA-DRB1 mismatch in the graft-versus-host direction and 2 or more HLA class I mismatches had protective effects. Our results so far confirm these findings [3]. Moreover, our historical experience with single antigen-mismatched related donors showed poor outcomes [21]. These results suggest that the use of a full haplotype-mismatched donor is preferred to harness the maximum graft-versus-tumor effect.

DONOR AGE: YOUNGER DONORS ARE BETTER

Younger donors have a more cellular bone marrow, and the immune system is subject to senescence with advancing age. Donor age has been correlated with survival in a large retrospective analysis of unrelated donor transplants facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program [22]. Higher incidence of grade III-IV aGVHD and chronic GVHD and lower overall survival was correlated with older donor age. The best outcomes were with donors age <30 years, and the worst were with donors age >45 years. These differences appeared more prominent in donors with mismatches [22]. These data clearly indicate a lower TRM with younger donors, and although no data exist on an association between donor age and outcomes of haploidentical HSCT, it is probably safe to assume that a younger male donor is preferred for transplantation. In female donors, age in general is correlated with parity. Older multiparous women may be the least preferred donors for male recipients, owing to a higher incidence of GVHD and lower overall survival in some studies, as discussed earlier. Taken together, our findings suggest that donor age and sex likely matter in transplantation of any type and might be more important in mismatched transplantation, owing to a potential greater incidence of GVHD.

KILLER IMMUNOGLOBULIN-LIKE RECEPTOR MISMATCH/NATURAL KILLER CELL ALLOREACTIVE DONOR

In a study of T cell—depleted haploidentical transplantation, Ruggeri et al. [23] found that natural killer (NK) cell alloreactivity predicted by killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) ligand donor—recipient mismatch was associated with a decreased rate of relapse and improved survival in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia, but not in those with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. This finding has remained controversial, with other investigators not reporting improved outcomes with a KIR-mismatched donor in either haploidentical or matched hematopoietic transplantation [24, 25]. Huang et al. [25] reported an increased incidence of GVHD and worse outcomes in T cell—replete haploidentical transplantations with a KIR—KIR ligand mismatch predicting NK cell alloreactivity; their treatment regimen did not include posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Recently, Symons et al. [26] reported a beneficial effect of KIR—KIR ligand mismatching in T cell—replete haploidentical HSCT using posttransplantation cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate as GVHD prophylaxis. Outcomes were better in patients with an inhibitory KIR haplotype, similar to the data reported by Cooley et al. [27] in matched unrelated donor transplantation. NK cells are important in the biology of haploidentical transplants, and strategies for selection of donors to optimize NK cell—mediated antitumor effects should be prospectively evaluated.

MALE VERSUS FEMALE DONOR, NONINHERITED MATERNAL AND PATERNAL ALLELES

Whether donor sex or noninherited maternal or paternal alleles affect transplantation outcomes is controversial. Traditionally, sex-matched donors have been the preferred source of stem cells for HSCT. This is due primarily to the higher incidence of GVHD in male recipients of female donor grafts, especially grafts from multiparous women, which is attributed to reactivity against H-Y minor histocompatibility antigens [28–32]. In studies of HSCT for malignancies, this risk was counterbalanced by a lower relapse rate, indicating that H-Y antigens also may be targets for the graft-versus-malignancy effect. Randolf et al. [29] reported an increased risk of grade II-IV aGVHD and a lower risk of relapse in male recipients of female donor grafts, with lower overall survival in this group. Several other studies have reported a greater risk of aGVHD or chronic GVHD in recipients of sex-mismatched donor grafts, with no differences in overall survival [30–32]. In T cell—replete haploidentical transplantation, evidence from the Chinese group also suggests improved transplantation outcomes in recipients of male donor grafts [33]. In multivariate analysis, Huo et al. [33] reported that a female donor, in addition to disease status, was associated with worse outcomes related to higher TRM. This same conclusion is supported by the Hopkins group in the article by Kasamon et al. [20], who also reported that a female donor for a male recipient was associated with worse outcomes.

Immunologic tolerance between the mother and the fetus during pregnancy has been reported to produce life long down-regulation of the immune responses and tolerance to the antigens of maternal origin, with potential lower alloreactivity in both the graft-versus-host and host-versus-graft (rejection) directions [34, 35]. Consequently, the use of donors with the mismatched (noninherited) haplotype of maternal origin rather than paternal origin could influence engraftment and transplantation outcomes.

This concept was initially demonstrated in solid organ transplantation. The use of related donors with a mismatched haplotype of maternal origin (ie, noninherited maternal antigen [NIMA]) compared with one of noninherited paternal antigen was associated with improved graft survival in renal transplant recipients [36]. Patients who received an NIMA-mismatched graft had similar graft survival as those who received a graft from a full HLA-identical donor [36].

Conflicting results have been reported in haploidentical HSCT. Polchi et al. [37] suggested, based on a small series of patients, that the use of maternal bone marrow stem cells allows the use of non—T cell—haploidentical grafts in children with advanced leukemia. A registry study from Japan reported a lower TRM and superior survival of patients with maternally derived rather than paternally derived bone marrow or peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells, more noticeably in recipients of HLA-mismatched grafts [38]. However, maternal grafts were found to be associated with higher risk of grade II-IV aGVHD and lower risk of relapse in patients with hematologic malignancies [38]. Subsequent work by van Rood et al. [39], in a Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research analysis, found a lower incidence of aGVHD in non—T cell—depleted haploidentical transplant recipients mismatched for NIMA compared with those mismatched for noninherited paternal antigen, but similar TRM and overall survival in the 2 groups of patients. Those authors also reported higher TRM and worse overall survival in HSCT with parental donors compared with HSCT with sibling donors [39].

Somewhat in disagreement with the foregoing results, Stern et al. [40] reported better outcomes in T cell—depleted haploidentical HSCT with maternal donors compared with paternal donors. The better survival was attributed to both a reduced incidence of relapse and TRM, and the effect was seen in both female and male recipients, suggesting that alloreactivity against minor histocompatibility antigens encoded by the Y chromosome did not play a major role. In contrast to parent-to-child transplantation, donor sex played no role in sibling transplantation in that study. The best outcomes were obtained with an NK-alloreactive mother as the donor [40].

Whether the presumably better tolerance associated with using NIMA-mismatched sibling or maternal donors is associated with better outcomes in T cell—replete haploidentical HSCT remains unclear. The primary barrier to answering this question is the relatively small number of adult patients with a known source of mismatch haplotype, given that parents are not usually HLA-typed.

CONCLUSION

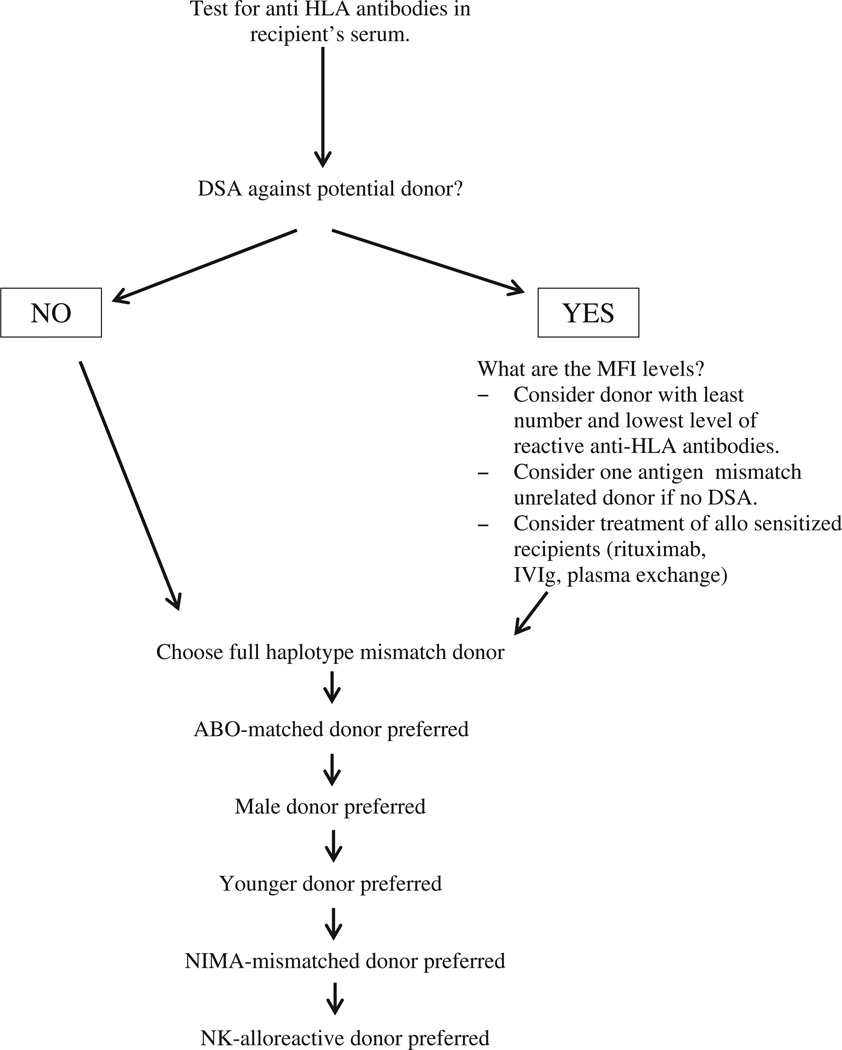

In conclusion, multiple related donors may be available for haploidentical HSCT, and several factors identified to affect transplantation outcomes should be considered in donor selection (Table 1, Figure 1). Our data indicate that avoidance of donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies, selection of young donors, and transplantation of a large hematopoietic cell dose improve outcome. The effects of KIR mismatch, donor sex, and noninherited maternal and paternal alleles are uncertain. Future studies involving larger numbers of patients are needed to clarify the importance of these and other immunogenic factors in selecting donors for haploidentical HSCT.

Table 1.

Factors Considered in Donor Selection for Haploidentical HSCT

| Factor | Primary Aim | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| DSA screen | Decrease TRM | Decreased risk of primary graft failure with HLA antibodies directed against donor HLA antigens |

| Young male donor | Decrease TRM | Greater cell dose yield |

| ABO match | Decrease TRM | Avoid an inadvertent decrease of infused cell dose associated with cell processing with a major ABO-mismatched donor |

| Full haplotype-mismatched donor | Decrease relapse | Possibly greater antitumor effect associated with a higher number of HLA mismatches |

| NK cell alloreactive donor | Decrease relapse | Potential antitumor effect generated by alloreactive NK cells |

| NIMA-mismatched donor | Decrease TRM | Potential better tolerance if the mismatched haplotype is of maternal origin |

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm for donor selection in haploidentical HSCT. DSA indicates donor–specific anti-HLA antibodies; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; NIMA, non-inherited maternal antigens; NK, natural killer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial disclosure: This paper was supported in part by an MD Anderson Institutional Research Grant to SOC.

References

- 1.Luznik L, Jalla S, Engstrom LW, et al. Durable engraftment of major histocompatibility complex—incompatible cells after nonmyeloablative conditioning with fludarabine, low-dose total body irradiation, and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Blood. 2001;98:3456–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunstein CG, Fuchs EJ, Carter SL, et al. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced-intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood. 2011;118:282–288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciurea SO, Mulanovich V, Saliba RM, et al. Improved early outcomes using a T-cell—replete graft compared with T cell—depleted haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.07.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciurea SO, de Lima M, Cano O, et al. High risk of graft failure in patients with anti-HLA antibodies undergoing haploidentical stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1019–1024. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b9d710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciurea SO, Thall PF, Wang X, et al. Donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies and graft failure in matched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:5957–5964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-362111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takanashi M, Atsuta A, Fujiwara K, et al. The impact of anti-HLA antibodies on unrelated cord blood transplantation. Blood. 116:2839–2846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249219. 200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutler C, Kim HT, Sun L, et al. Donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies predict outcomes in double umbilical cord blood transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:6691–6697. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu H, Chilton PM, Tanner MK, et al. Humoral immunity is the dominant barrier for allogeneic bone marrow engraftment in sensitized recipients. Blood. 108:3611–3619. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshihara S, Maruya E, Taniguchi K, et al. Risk and prevention of graft failure in patients with preexisting donor-specific HLA antibodies undergoing unmanipulated haploidentical SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:508–515. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocha V, Labopin M, Gluckman E, et al. Relevance of bone marrow cell dose on allogeneic transplantation outcomes for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first CR: results of a European survey. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4324–4330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominietto A, Lamparelli AM, Van Lint MT, et al. Transplant-related mortality and long-term graft function are significantly influenced by cell dose in patients undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100:3930–3934. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorin NC, Labopin M, Rocha V, et al. Marrow versus peripheral blood for geno-identical allogeneic stem cell transplantation in acute myelocytic leukemia: influence of dose and stem cell source shows better outcomes. Blood. 2003;102:3043–3051. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachar-Lustig E, Rachamim N, Li HW, et al. Megadose of T cell—depleted bone marrow overcomes MHC barriers in sublethally irradiated mice. Nat Med. 1995;1:1268–1273. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reisner Y, Bachar-Lustig E, Li HW, et al. The role of megadose CD34+ progenitor cells in the treatment of leukemia patients without a matched donor and in tolerance induction for organ transplantation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;872:336–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gajewski J, Johnson VV, Sandler SG, et al. A review of transfusion practice before, during and after hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation. Blood. 2008;112:3036–3047. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guttridge MG, Sidders C, Booth-Davey E, et al. Factors affecting volume reduction and red blood cell depletion of bone marrow on the COBE Spectra cell separator before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:175–181. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morishima Y, Sasazuki T, Inoko H, et al. The clinical significance of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele compatibility in patients receiving a marrow transplant from serologically HLA matched HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2002;99:4200–4206. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flomenberg N, Baxter-Lowe LA, Confer D, et al. Impact of HLA class I and class II high-resolution matching on outcomes of unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation: HLA-C mismatching is associated with a strong adverse effect on transplantation outcome. Blood. 2004;104:1923–1930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SJ, Klein J, Haagerson M, et al. High-resolution HLA matching contributes to the success of unrelated donor marrow transplantation. Blood. 2007;110:4576–4583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasamon YL, Luznik L, Leffell MS, et al. Nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with high-dose post-transplant cyclophosphamide: effect of HLA disparity on outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciurea SO, Saliba RM, Rondon G, et al. Outcomes of patients with myeloid malignancies treated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors compared with one human leukocyte antigen mismatch related donors using HLA typing at 10 loci. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kollman C, Howe CW, Anasetti C, et al. Donor characteristics as risk factors in recipients after transplantation of bone marrow from unrelated donors: the effect of donor age. Blood. 2001;98:2043–2051. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Burchielli E, et al. NK cell alloreactivity and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Science. 2008;40:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gagne K, Brizard G, Gueglio B, et al. Relevance of KIR gene polymorphisms in bone marrow transplantation outcome. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:271–280. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang XJ, Zhao XY, Liu DH, et al. Deleterious effects of KIR ligand incompatibility on clinical outcomes in haploidentical hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation without in vitro T-cell depletion. Leukemia. 2007;21:848–851. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Symons HJ, Leffell MS, Rossiter ND, et al. Improved survival with inhibitory killer immunoglobulin receptor (KIR) gene mismatched and KIR haplotype B donors after nonmyeloablative, HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, Guethlein LA, et al. Donor selection for natural killer receptor genes leads to superior survival after unrelated transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:2411–2419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bross DS, Tutschka PJ, Farmer ER, et al. Predictive factors for acute graft-versus-host disease in patients transplanted with HLA-identical bone marrow. Blood. 1984;63:1265–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randolph SSB, Gooley TA, Warren EH, et al. Female donors contribute to a selective graft-versus-leukemia effect in male recipients of HLA-matched, related hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Blood. 2004;103:347–352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisdorf D, Hakke R, Blazar B, et al. Risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease in histocompatible donor marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1991;51:1197–1203. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199106000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlens S, Rihgden O, Remberger M, et al. Risk factors for chronic graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective single-center analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:755–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loren AW, Bunin GR, Boudreau C, et al. Impact of donor and recipient sex and parity on outcomes of HLA-identical sibling allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:758–769. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huo MR, Xu LP, Li D, et al. The effect of HLA disparity on clinical outcomes after HLA-haploidentical blood and marrow transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:284–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris DT, Schumacher MJ, LoCascio J, et al. Immunoreactivity of umbilical cord blood and postpartum maternal peripheral blood with regard to HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;14:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Claas FH, Gijbels Y, van der Velden-de Munck J, et al. Induction of B cell unresponsiveness to noninherited maternal HLA antigens during fetal life. Science. 1988;24:1815–1817. doi: 10.1126/science.3051377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burlingham WJ, Grailer AP, Heisey DM, et al. The effect of tolerance to noninherited maternal HLA antigens on the survival of renal transplants from sibling donors. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1657–1664. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812033392302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polchi P, Lucarelli G, Galimberti M, et al. Haploidentical bone marrow transplantation from mother to child with advanced leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;16:529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamacki S, Ichinohe T, Matsuo K, et al. Superior survival of blood and marrow stem cell recipients given maternal grafts over recipients given paternal grafts. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:375–380. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Rood JJ, Loberiza FR, Jr, Zhang MJ, et al. Effect of tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens on the occurrence of graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation from a parent or an HLA-haplodentical sibling. Blood. 2002;99:1572–1577. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stern M, Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, et al. Survival after T cell-depleted haploidentical stem cell transplantation is improved using the mother as donor. Blood. 2008;112:2990–2995. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-135285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]